Teaching the N-Word

This essay is published in conjunction with the No Safety Net Series theater festival performances of Underground Railroad Game. UMS Presents Underground Railroad Game on January 17-21, 2018 at the Arthur Miller Theatre in Ann Arbor.

“Teaching the N-Word” is written by Emily Bernard. Dr. Bernard is a professor of English and Critical Race and Ethnic Studies at the University of Vermont. She is working on a collection of essays called Black Is the Body.

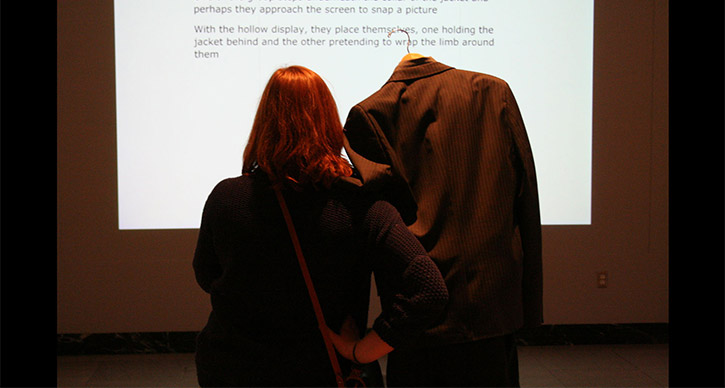

Photo: Underground Railroad Game. Courtesy of artist.

Once riding in old Baltimore,

Heart-filled, head-filled with glee,

I saw a Baltimorean

Keep looking straight at me.

Now I was eight and very small,

And he was no whit bigger,

And so I smiled, but he poked out

His tongue, and called me, “Nigger.”

I saw the whole of Baltimore

From May until December;

Of all the things that happened there

That’s all that I remember.

—Countee Cullen, “Incident” (1925)

October 2004

Eric is crazy about queer theory. I think it is safe to say that Eve Sedgwick, Judith Butler, and Lee Edelman have changed his life. Every week, he comes to my office to report on the connections he is making between the works of these writers and the books he is reading for the class he is taking with me, African-American autobiography.

I like Eric. So tonight, even though it is well after six and I am eager to go home, I keep our conversation going. I ask him what he thinks about the word “queer,” whether or not he believes, independent of the theorists he admires, that epithets can ever really be reclaimed and reinvented.

“‘Queer’ has important connotations for me,” he says. “It’s daring, political. I embrace it.” He folds his arms across his chest, and then unfolds them.

I am suspicious.

“What about ‘nigger’?” I ask. “If we’re talking about the importance of transforming hateful language, what about that word?” From my bookshelf I pull down Randall Kennedy’s book Nigger: The Strange Career of a Troublesome Word, and turn it so its cover faces Eric. “Nigger,” in stark white type against a black background, is staring at him, staring at anyone who happens to be walking past the open door behind him.

Over the next 30 minutes or so, Eric and I talk about “nigger.” He is uncomfortable; every time he says “nigger,” he drops his voice and does not meet my eyes. I know that he does not want to say the word; he is following my lead. He does not want to say it because he is white; he does not want to say it because I am black. I feel my power as his professor, the mentor he has so ardently adopted. I feel the power of Randall Kennedy’s book in my hands, its title crude and unambiguous. Say it, we both instruct this white student. And he does.

It is late. No one moves through the hallway. I think about my colleagues, some of whom still sit at their own desks. At any minute, they might pass my office on their way out of the building. What would they make of this scene? Most of my colleagues are white. What would I think if I walked by an office and saw one of them holding up Nigger to a white student’s face? A black student’s face?

“I think I am going to add ‘Who Can Say Nigger?’ to our reading for next week,” I say to Eric. “It’s an article by Kennedy that covers some of the ideas in this book.” I tap Nigger with my finger, and then put it down on my desk.

“I really wish there was a black student in our class,” Eric says as he gathers his books to leave.

Photo: Underground Railroad Game. Courtesy of the artist.

As usual I have assigned way too much reading. Even though we begin class discussion with references to three essays required for today, our conversation drifts quickly to “Who Can Say Nigger?” and plants itself there. We talk about the word, who can say it, who won’t say it, who wants to say it, and why. There are 11 students in the class. All of them are white.

Our discussion is lively and intense; everyone seems impatient to speak. We talk about language, history, and identity. Most students say “the n-word” instead of “nigger.” Only one or two students actually use the word in their comments. When they do, they use the phrase “the word ‘nigger,’” as if to cushion it. Sometimes they make quotations marks with their fingers. I notice Lauren looking around. Finally, she raises her hand.

“I have a question; it’s somewhat personal. I don’t want to put you on the spot.”

“Go ahead, Lauren,” I say with relief.

“Okay, so how does it feel for you to hear us say that word?”

I have an answer ready.

“I don’t enjoy hearing it. But I don’t think that I feel more offended by it than you do. What I mean is, I don’t think I have a special place of pain inside of me that the word touches because I am black.” We are both human beings, I am trying to say. She nods her head, seemingly satisfied. Even inspired, I hope.

I am lying, of course.

I am grateful to Lauren for acknowledging my humanity in our discussion. But I do not want me—my feelings, my experiences, my humanity—to become the center of classroom discussion. Here at the University of Vermont, I routinely teach classrooms full of white students. I want to educate them, transform them. I want to teach them things about race they will never forget. To achieve this, I believe I must give of myself. I want to give to them—but I want to keep much of myself to myself. How much? I have a new answer to this question every week.

I always give my students a lecture at the beginning of every African-American studies course I teach. I tell them, in essence, not to confuse my body with the body of the text. I tell them that while it would be disingenuous for me to suggest that my own racial identity has nothing to do with my love for African-American literature, my race is only one of the many reasons why I stand before them. “I stand here,” I say, “because I have a Ph.D., just like all your other professors.” I make sure always to tell them that my Ph.D., like my B.A., comes from Yale.

“In order to get this Ph.D.,” I continue, “I studied with some of this country’s foremost authorities on African-American literature, and a significant number of these people are white.

“I say this to suggest that if you fail to fully appreciate this material, it is a matter of your intellectual laziness, not your race. If you cannot grasp the significance of Frederick Douglass’s plight, for instance, you are not trying hard enough, and I will not accept that.”

I have another part of this lecture. It goes: “Conversely, this material is not the exclusive property of students of color. This is literature. While these books will speak to us emotionally according to our different experiences, none of us is especially equipped to appreciate the intellectual and aesthetic complexities that characterize African-American literature. This is American literature, American experience, after all.”

Sometimes I give this part of my lecture, but not always. Sometimes I give it and then regret it later.

Photo: Underground Railroad Game. Courtesy of the artist.

As soon as Lauren asks me how I feel, it is as if the walls of the room soften and collapse slightly, nudging us a little bit closer together. Suddenly, 11 pairs of eyes are beaming sweet messages at me. I want to laugh. I do. “Look at you all, leaning in,” I say. “How close we have all become.”

I sit at the end of a long narrow table. Lauren usually sits at the other end. The rest of the students flank us on either side. When I make my joke, a few students, all straight men, I notice, abruptly pull themselves back. They shift their eyes away from me, look instead at their notebooks, the table. I have made them ashamed to show that they care about me, I realize. They are following the cues I have been giving them since the beginning of the semester, cues that they should take this class seriously, that I will be offended if they do not. “African-American studies has had to struggle to exist at all,” I have said. “You owe it your respect.” Don’t be too familiar, is what I am really saying. Don’t be too familiar with me.

Immediately, I regret having made a joke of their sincere attempt to offer me their care. They want to know me; they see this moment as an opportunity. But I can’t stop. I make more jokes, mostly about them, and what they are saying and not saying. I can’t seem to help myself.

Eric, who is sitting near me, does not recoil at my jokes; he does not respond to my not-so-subtle efforts to push him and everyone else back. He continues to lean in, his torso flat against the edge of the table. He looks at me. He raises his hand.

“Emily,” he says, “would you tell them what you told me the other day in your office? You were talking about how you dress and what it means to you.” “Yes,” I begin slowly. “I was telling Eric about how important it is to me that I come to class dressed up.”

“And remember what you said about Todd? You said that Todd exercises his white privilege by dressing so casually for class.”

Todd is one of my closest friends in the English department. His office is next door to mine. I don’t remember talking about Todd’s clothing habits with Eric, but I must have. I struggle to come up with a comfortably vague response to stop Eric’s prodding. My face grows hot. Everyone is waiting.

“Well, I don’t know if I put it exactly like that, but I do believe that Todd’s style of dress reflects his ability to move in the world here—everywhere, really—less self-consciously than I do.” As I sit here, I grow increasingly more alarmed at what I am revealing: my personal philosophies; my attitudes about my friend’s style of dress; my insecurities; my feelings. I quietly will Eric to stop, even as I am impressed by his determination. I meet his eyes again.

“And you. You were saying that the way you dress, it means something, too,” Eric says. On with this tug of war, I think.

I relent, let go of the rope. “Listen, I will say this. I am aware that you guys, all of my students at UVM, have very few black professors. I am aware, in fact, that I may be the first black teacher many of you have ever had. And the way I dress for class reflects my awareness of that possibility.” I look sharply at Eric. That’s it. No more.

Photo: Underground Railroad Game. Courtesy of the artist.

September 2004

On the first day of class, Nate asks me what I want to be called.

“Oh, I don’t know,” I say, fussing with equipment in the room. I know. But I feel embarrassed, as if I have been found out. “What do you think?” I ask them.

They shuffle around, equally embarrassed. We all know that I have to decide, and that whatever I decide will shape our classroom dynamic in very important ways.

“What does Gennari ask you to call him?” I have inherited several of these students from my husband, John Gennari, another professor of African- American studies. He is white.

“Oh, we call him John,” Nate says with confidence. I am immediately envious of the easy warmth he seems to feel for John. I suspect it has to do with the name thing.

“Well, just call me Emily, then. This is an honors class, after all. And I do know several of you already. And then wouldn’t it be strange to call the husband John and the wife Professor?” Okay, I have convinced myself.

Nate says, “Well, John and I play basketball in a pickup game on Wednesdays. So, you know, it would be weird for me to be checking him and calling him ‘Professor Gennari.’”

We all laugh, and move on to other topics. But my mind locks onto an image of my husband and Nate on the basketball court, two white men, covered in sweat, body to body, heads down, focused on the ball.

October 2004

“It’s not that I can’t say it, it’s that I don’t want to. I will not say it,” Sarah says. She wears her copper red hair in a short, smart style that makes her look older than her years. When she smiles I remember how young she is. She is not smiling now. She looks indignant. She is indignant because I am insinuating that there is a problem with the fact that no one in the class will say “nigger.” Her indignation pleases me.

Good.

“I’d just like to remind you all that just because a person refuses to say ‘nigger,’ that doesn’t mean that person is not a racist,” I say. They seem to consider this.

“And another thing,” Sarah continues. “About dressing for class? I dislike it when my professors come to class in shorts, for instance. This is a profession. They should dress professionally.”

Later, I tell my husband, John, about our class discussion. When I get to Sarah’s comment about professors in shorts, he says, “Good for her.”

I hold up Nigger and show its cover to the class. I hand it to the person on my left, gesture for him to pass the book around the room.

“Isn’t it strange that when we refer to this book, we keep calling it ‘the n-word’?”

Lauren comments on the affect of one student who actually said it. “Colin looked like he was being strangled.” Of the effect on the other students, she says, “I saw us all collectively cringing.”

“Would you be able to say it if I weren’t here?” I blurt.

A few students shake their heads. Tyler’s hand shoots up. He always sits directly to my right.

“That’s just bullshit,” he says to the class, and I force myself not to raise an eyebrow at bullshit. “If Emily weren’t here, you all would be able to say that word.”

I note that he, himself, has not said it, but do not make this observation out loud.

“No.” Sarah is firm. “I just don’t want to be the kind of person who says that word, period.”

“Even in this context?” I ask.

“Regardless of context,” Sarah says.

“Even when it’s the title of a book?”

I tell the students that I often work with a book called Nigger Heaven, written in 1926 by a white man, Carl Van Vechten.

“Look, I don’t want to give you the impression that I am somehow longing for you guys to say ‘nigger,’” I tell them, “but I do think that something is lost when you don’t articulate it, especially if the context almost demands its articulation.”

“What do you mean? What exactly is lost?” Sarah insists.

“I don’t know,” I say. I do know. But right here, in this moment, the last thing I want is to win an argument that winds up with Sarah saying “nigger” out loud.

Throughout our discussion, Nate is the only student who will say “nigger” out loud. He sports a shearling coat and a Caesar haircut. He quotes Jay-Z. He makes a case for “nigga.” He is that kind of white kid; he is down. “He is so down, he’s almost up,” Todd will say in December, when I show him the title page of Nate’s final paper for this class. The page contains one word, “Nigger,” in black type against a white background. It is an autobiographical essay. It is a very good paper.

October 1994

Nate reminds me of a student in the very first class I taught all on my own, a senior seminar called “Race and Representation.” I was still in graduate school. It was 1994 and Pulp Fiction had just come out. I spent an entire threehour class session arguing with my students over the way race was represented in the movie. One student, in particular, passionately resisted my attempts to analyze the way Tarantino used “nigger” in the movie.

“What is his investment in this word? What is he, as the white director, getting out of saying ‘nigger’ over and over again?” I asked.

After some protracted verbal arm wrestling, the student gave in.

“Okay, okay! I want to be the white guy who can say ‘nigger’ to black guys and get away with it. I want to be the cool white guy who can say ‘nigger.’”

“Thank you! Thank you for admitting it!” I said, and everyone laughed.

He was tall. He wore tie-dye T-shirts and had messy, curly brown hair. I don’t remember his name.

Photo: Underground Railroad Game. Courtesy of the artist.

After Pulp Fiction came out, I wrote my older brother an earnest, academic e-mail. I wanted to “initiate a dialogue” with him about the “cultural and political implications of the various usages of ‘nigger’ in popular culture.”

His one-sentence reply went something like this: “Nigga, niggoo, niggu, negreaux, negrette, niggrum.”

“Do you guys ever read The Source magazine?” In 1994, my students knew about The Source; some of them had read James Bernard’s column, “Doin’ the Knowledge.”

“He’s my brother,” I said, not bothering to mask my pride with anything like cool indifference. “He’s coming to visit class in a couple of weeks, when we discuss hip-hop culture.”

The eyes of the tie-dyed student glistened.

“Quentin Tarantino is a cool-ass white boy!” James said on the day he came to visit my class. “He is one cool white boy.”

My students clapped and laughed.

“That’s what I said,” my tie-dyed student sighed.

James looked at me slyly. I narrowed my eyes at him. Thanks a lot.

September 2004

On the way to school in the morning, I park my car in the Allen House lot. Todd was the one who told me about the lot. He said, “Everyone thinks the lot at the library is closer, but the lot behind Allen House is so much better. Plus, there are always spaces, in part because everyone rushes for the library.”

It is true that the library lot is nearly always full in the morning. It’s also true that the Allen House lot is relatively empty, and much closer to my office. But if it were even just slightly possible for me to find a space in the library lot, I would probably try to park there, for one reason. To get to my office from Allen House, I have to cross a busy street. To get to my office from the library, I do not.

Several months ago, I was crossing the same busy street to get to my office after a class. It was late April, near the end of the semester, and it seemed as if everyone was outside. Parents were visiting, and students were yelling to each other, introducing family members from across the street. People smiled at me—wide, grinning smiles. I smiled back. We were all giddy with the promise of spring, which always comes so late in Vermont, if it comes at all.

Traffic was heavy, I noticed as I walked along the sidewalk, calculating the moment when I would attempt to cross. A car was stopped near me; I heard rough voices. Out of the corner of my eye, I looked into the car: all white. I looked away, but I could feel them surveying the small crowd that was carrying me along. As traffic picked up again, one of the male voices yelled out, “Queers! Fags!” There was laughter. Then the car roared off.

I was stunned. I stopped walking and let the words wash over me. Queer. Fag. Annihilating, surely. I remembered my role as a teacher, a mentor, in loco parentis, even though there were real parents everywhere. I looked around to check for the wounds caused by those hateful words. I peered down the street: too late for a license plate. All around me, students and parents marched to their destinations, as if they hadn’t heard. Didn’t you hear that? I wanted to shout.

All the while I was thinking, Not nigger. Not yet.

October 2004

Nate jumps in.

“Don’t you grant a word power by not saying it? Aren’t we, in some way, amplifying its ugliness by avoiding it?” He asks.

“I am afraid of how I will be affected by saying it,” Lauren says. “I just don’t want that word in my mouth.”

Tyler remembers a phrase attributed to Farai Chideya in Randall Kennedy’s essay. He finds it and reads it to us. “She says that the n-word is the ‘trump card, the nuclear bomb of racial epithets.’”

“Do you agree with that?” I ask.

Eleven heads nod vigorously.

“Nuclear bombs annihilate. What do you imagine will be destroyed if you guys use the word in here?”

Shyly, they look at me, all of them, and I understand. Me. It is my annihilation they imagine.

November 2004

Some of My Best Friends, my anthology of essays about interracial friendship, came out in August, and the publicity department has arranged for various interviews and other promotional events. When I did an on-air interview with a New York radio show, one of the hosts, Janice, a black woman, told me that the reason she could not marry a white man was because she believed if things ever got heated between them, the white man would call her a nigger. I nodded my head. I had heard this argument before. But strangely I had all but forgotten it. The fact that I had forgotten to fear “nigger” coming from the mouth of my white husband was more interesting to me than her fear, alive and ever-present.

“Are you bi-racial?”

“No.”

“Are you married to a white man?”

“Yes.”

These were among the first words exchanged between Janice, the radio host, and me. I could tell—by the way she looked at me, and didn’t look at me; by the way she kept her body turned away from me; by her tone—that she had made up her mind about me before I entered the room. I could tell that she didn’t like what she had decided about me, and that she had decided I was the wrong kind of black person. Maybe it was what I had written in Some of My Best Friends. Maybe it was the fact that I had decided to edit a collection about interracial friendships at all. When we met, she said, “I don’t trust white people,” as decisively and exactly as if she were handing me her business card. I knew she was telling me that I was foolish to trust them, to marry one. I was relieved to look inside myself and see that I was okay, I was still standing. A few years ago, her silent judgment—this silent judgment from any black person—would have crushed me.

When she said she could “tell” I was married to a white man, I asked her how. She said, “Because you are so friendly,” and did a little dance with her shoulders. I laughed.

But Janice couldn’t help it; she liked me in spite of herself. As the interview progressed, she let the corners of her mouth turn up in a smile. She admitted that she had a few white friends, even if they sometimes drove her crazy. At a commercial break, she said, “Maybe I ought to try a white man.” She was teasing me, of course. She hadn’t changed her mind about white people, or dating a white man, but she had changed her mind about me. It mattered to me. I took what she was offering. But when the interview was over, I left it behind.

My husband thought my story about the interview was hilarious. When I got home, he listened to the tape they gave me at the station. He said he wanted to use the interview in one of his classes.

A few days later, I told him what Janice said about dating a white man, that she won’t because she is afraid he will call her a nigger. As I told him, I felt an unfamiliar shyness creep up on me.

“That’s just so far out of . . . it’s not in my head at all.” He was having difficulty coming up with the words he wanted, I could tell. But that was okay. I knew what he meant. I looked at him sitting in his chair, the chair his mother gave us. I can usually find him in that chair when I come home. He is John, I told myself. And he is white. No more or less John and no more or less white than he was before the interview, and Janice’s reminder of the fear that I had forgotten to feel.

Photo: Underground Railroad Game. Courtesy of the artist.

I tell my students in the African-American autobiography class about Janice. I say, “You would not believe the indignities I have suffered in my humble attempts to ‘move this product,’ as they say in publishing.” I say, “I have been surrounded by morons, and now I gratefully return to the land of the intellectually agile.” They laugh.

I flatter them, in part because I feel guilty that I have missed so many classes in order to do publicity for my book. But I cringe, thinking of how I have called Janice, another black woman, a “moron” in front of these white students. I do not tell my students she is black.

“Here is a story for your students,” John tells me. We are in the car, on our way to Cambridge for the weekend. “The only time I ever heard ‘nigger’ in my home growing up was when my father’s cousin was over for a visit. It was 1988, I remember. Jesse Jackson was running for president. My father’s cousin was sitting in the kitchen, talking to my parents about the election. ‘I’m going to vote for the nigger,’ my father’s cousin said. ‘He’s the only one who cares about the workingman.’”

John laughs. He often laughs when he hears something extraordinary, whether it’s good or bad.

“That’s fascinating,” I say.

The next time class meets, I tell my students this story.

“So what do we care about in this sentence?” I say. “The fact that John’s father’s cousin used a racial epithet, or the fact that his voting for Jackson conveys a kind of ultimate respect for him? Isn’t his voting for Jackson more important for black progress than how his father’s cousin feels?”

I don’t remember what the students said. What I remember is that I tried to project for them a sense that I was untroubled by saying “nigger,” by my husband’s saying “nigger,” by his father’s cousin’s having said “nigger,” by his parents’—my in-laws—tolerance of “nigger” in their home, years ago, long before I came along. What I remember is that I leaned on the word “feels” with a near-sneer in my voice. It’s an intellectual issue, I beamed at them, and then I directed it back at myself. It has nothing to do with how it makes me feel.

After my interview with Janice, I look at the white people around me differently, as if from a distance. I do this, from time to time, almost as an exercise. I even do it to my friends, particularly my friends. Which of them has “nigger” in the back of her throat?

I go out for drinks with David, my senior colleague. It is a ritual. We go on Thursdays after class, always to the same place. I know that he will order, in succession, two draft beers, and that he will ask the waitress to help him choose the second. “What do you have on draft that is interesting tonight?” he will say. I order red wine, and I, too, always ask the waitress’s advice. Then, we order a selection of cheeses, again soliciting assistance. We have our favorite waitresses. We like the ones who indulge us.

Tonight, David orders a cosmopolitan.

We never say it, but I suspect we both like the waitresses who appreciate the odd figure we cut. He is white, 60-something, male. I am black, 30-something, female. Not such an odd pairing elsewhere, perhaps, but uncommon in Burlington, insofar as black people are uncommon in Burlington.

Something you can’t see is that we are both from the South. Different Souths, perhaps, 30 years apart, black and white. I am often surprised by how much I like his company. All the way up here, I sometimes think when I am with him, and I am sitting with the South, the white South that, all of my childhood, I longed to escape. I once had a white boyfriend from New Orleans. “A white Southerner, Emily?” My mother asked, and sighed with worry. I understood. We broke up.

David and I catch up. We talk about the writing we have been doing. We talk each other out of bad feelings we are harboring against this and that person. (Like most Southerners, like the South in general, David and I have long memories.) We talk about classes. I describe to him the conversation I have been having with my students about “nigger.” He laughs at my anecdotes.

I am on my second glass of wine. I try to remember to keep my voice down. It’s a very nice restaurant. People in Burlington do not want to hear “nigger” while they are eating a nice dinner, I say, chastising myself. I am tipsy.

As we leave, I accidentally knock my leg against a chair. You are drunk, I tell myself. You are drunk and black in a restaurant in Burlington. What were you thinking? I feel eyes on me as I walk out of the restaurant, eyes that may have been focused elsewhere, as far as I know, because I do not allow myself to look.

Later that evening, I am alone. I remember that David recently gave me a poem of his to read, a poem about his racist grandmother, now dead, whom he remembers using the word “nigger” often and with relish. I lie in bed and reconstruct the scene of David and me in the restaurant, our conversation about “nigger.” Was his grandmother at the table with us all along?

The next day, I see David in his office, which is next to mine, on the other side from Todd. I knock on the door. He invites me in. I sit in a chair, the chair I always sit in when I come to talk to him. He tells me how much he enjoyed our conversation the night before.

“Me, too,” I say. “But today it’s as if I’m looking at you across from something,” I say. “It has to do with race.” I blame a book I am reading, a book for my African-American autobiography class, Toi Derricote’s The Black Notebooks. “Have you read it?” David is a poet, like Derricote.

“No, but I know Toi and enjoy her poetry. Everything I know about her and her work would lead me to believe that I would enjoy that book.” He is leaning back in his chair, his arms folded behind his head.

“Well, it’s making me think about things, remember the ways that you and I will always be different,” I say abruptly.

David laughs. “I hope not.” He looks puzzled.

“It’s probably just temporary.” I don’t ask him my question about his grandmother, whether or not she is always somewhere with him, in him, in the back of his throat.

John is at an African-American studies conference in New York. Usually, I am thrilled to have the house to myself for a few days. But this time, I mope. I sit at the dining-room table, write this essay, watch out of the window.

Today, when John calls, he describes the activity at the conference. He tells me delicious and predictable gossip about people we know, and the divas that we know of. The personalities, the in-fighting—greedily, we sift over details on the phone.

“Did you enjoy your evening with David last night?” he asks.

“I did, very much,” I say. “But give me more of the who-said-what.” I know he’s in a hurry. In fact, he’s talking on a cell phone (my cell phone; he refuses to get one of his own) as he walks down a New York street.

“Oh, you know these Negroes.” His voice jounces as he walks.

“Yeah,” I say, laughing. I wonder who else can hear him.

Todd is married to Hilary, another of my close friends in the department. She is white. Like John, Todd is out of town this weekend. Since their two boys were born, our godsons, John and I see them less frequently than we used to. But Hilary and I are determined to spend some time together on this weekend with our husbands away.

Burlington traffic keeps me away from her and the boys for an hour, even though she lives only blocks away from me. When I get there, the boys are ready for their baths, one more feeding, and then bed. Finally, they are down, and we settle into grown-up conversation. I tell her about my class, our discussions about “nigger,” and my worries about David.

“That’s the thing about the South,” Hilary says. I agree, but then start to wonder about her grandmother. I decide I do not want to know, not tonight.

I do tell her, however, about the fear I have every day in Burlington, crossing that street to get back and forth from my office, what I do to guard myself against the fear.

“Did you grow up hearing that?” She asks. Even though we are close, and alone, she does not say the word.

I start to tell her a story I have never told anyone. It is a story about the only time I remember being called a nigger to my face.

“I was a teenager, maybe 16. I was standing on a sidewalk, trying to cross a busy street after school, to get to the mall and meet my friends. I happened to make eye contact with a white man in a car that was sort of stopped—traffic was heavy. Anyway, he just said it, kind of spit it up at me.”

“Oh, that’s why,” I say, stunned, remembering the daily ritual I have just confessed to her. She looks at me, just as surprised.

Photo: Underground Railroad Game. Courtesy of the artist.

December 2004

I am walking down a Burlington street with my friend, Anh. My former quilting teacher, Anh is several years younger than I am. She has lived in Vermont her whole life. She is Vietnamese; her parents are white. Early in our friendship, she told me her father was a logger, as were most of the men in her family. Generations of Vietnamese loggers in Vermont, I mused. It wasn’t until I started to describe her to someone else that I realized she must be adopted.

Anh and I talk about race, about being minorities in Burlington, but we usually do it indirectly. In quilting class, we would give each other looks sometimes that said, You are not alone, or Oh, brother, when the subject of race came up in our class, which was made up entirely of white women, aside from the two of us.

There was the time, for instance, when a student explained why black men found her so attractive. “I have a black girl’s butt,” she said. Anh and I looked at each other: Oh, brother. We bent our heads back over our sewing machines.

As we walk, I tell Anh about my African-American autobiography class, the discussions my students and I have been having about “nigger.” She listens, and then describes to me the latest development in her on-again, offagain relationship with her 50-year-old boyfriend, another native Vermonter, a blond scuba instructor.

“He says everything has changed,” she tells me. “He’s going clean up the messes in his life.” She laughs.

Once, Anh introduced me to the boyfriend she had before the scuba instructor when I ran into them at a restaurant. He is also white.

“I’ve heard a lot about you,” I said, and put out my hand.

“I’ve never slept with a black woman,” he said, and shook my hand. There was wonder in his voice. I excused myself and went back to my table. Later, when I looked over at them, they were sitting side by side, not speaking.

Even though Anh and I exchanged our usual glances that night, I doubted that we would be able to recover our growing friendship. Who could she be, dating someone like that? The next time I heard from her, months later, she had broken up with him.

I am rooting for the scuba instructor.

“He told me he’s a new person,” she says.

“Well, what did you say?” I ask her.

“In the immortal words of Jay-Z, I told him, ‘Nigga, please.’”

I look at her, and we laugh.

In lieu of a final class, my students come over for dinner. One by one, they file in. John takes coats while I pretend to look for things in the refrigerator. I can’t stop smiling.

“The books of your life” is the topic for tonight. I have asked them to bring a book, a poem, a passage, some art that has affected them. Hazel has brought a children’s book. Tyler talks about Saved by the Bell. Nate talks about Freud.

Dave has a photograph. Eric reads “The Seacoast of Despair” from Slouching Towards Bethlehem.

I read from Annie John by Jamaica Kincaid. Later I will wonder why I did not read “Incident” by Countee Cullen, the poem that has been circulating in my head ever since we began our discussion about “nigger.” What held me back from bringing “Incident” to class? The question will stay with me for months.

The night of our dinner is an emotional one. I tell my students that they are the kind of class a professor dreams about. They give me a gift certificate to the restaurant that David and I frequent. I give them copies of Some of My Best Friends and inscribe each one. Eric demands a hug, and then they all do; I happily comply. We talk about meeting again as a class, maybe once or twice in the spring. The two students who will be abroad promise to keep in touch through our Listserv, which we all agree to keep going until the end of the school year, at least. After they leave, the house is quiet and empty.

Weeks later, I post “Incident” on our Listserv and ask them to respond with their reactions. Days go by, then weeks. Silence. After more prodding, finally Lauren posts an analysis of the poem, and then her personal reactions to it. I thank her online, and ask for more responses. Silence.

I get e-mails and visits from these students about other matters, some of them race-related. Eric still comes by my office regularly. Once he brings his mother to meet me, a kind and engaging woman who gives me a redolent candle she purchased in France, and tells me her son enjoyed “African-American Autobiography.” Eric and I smile at each other.

A few days later, I see Eric outside the campus bookstore.

“What did you think about ‘Incident’?”

“I’ve been meaning to write you about it. I promise I will.”

In the meantime, Nigger is back in its special place on my bookshelf. It is tucked away so that only I can see the title on its spine, and then only with some effort.

This essay is published in conjunction with the No Safety Net Series theater festival performances of Underground Railroad Game. UMS Presents Underground Railroad Game on January 17-21, 2018 at the Arthur Miller Theatre in Ann Arbor.

“Teaching the N-Word” is written by Emily Bernard. Dr. Bernard is a professor of English and Critical Race and Ethnic Studies at the University of Vermont. She is working on a collection of essays called Black Is the Body.

Artist Interview: Actress Aisling O’Sullivan of The Beauty Queen of Leenane

Editor’s Note: University of Michigan student Zoey Bond spent several weeks with Druid Theatre Company as part of the UMS 21st Century Artist Internship program. The Company returns to Ann Arbor with a new production of Martin McDonagh’s dark comedy The Beauty Queen of Leenane on March 9-11, 2017. The interview below is with Aisling O’Sullivan, the Irish actress who plays the beauty queen of Leenane.

Photo: The Beauty Queen of Leenane’s Aisling O’Sullivan (left) and Marie Mullen (right). Photo by Matthew Thompson.

Zoey Bond: You’ve worked on playwright Martin McDonagh’s text before, what draws you to his writing?

Aisling O’Sullivan: It’s his characters, the dilemmas, and the wit, I suppose. It’s more than just the writing. It’s the delight I get from performing in the plays, which is so much fun to do and challenging. They are deep. They’ve got all of the colors.

ZB: As you know, this new production casts Marie Mullen in the role of the scheming mother. She won a Tony Award for the role of the daughter in the 1996 Broadway production. Last week you started wearing Marie’s boots in rehearsal, so you were quite literally stepping into her shoes. What has this part of the process been like?

AO: I found it very difficult. In the past, if I’ve seen a performance, and then I have to do my performance, I think I can do better. I don’t feel I can better than Marie. I saw her originally, and she is just extraordinary and really painfully beautiful. It would have been one of Marie’s defining performances. I’ve known her for a long time, so stepping into her shoes, I’m trying to embrace it and go, “Okay, so I’m privileged to be asked by the same director who thinks there is something I can do that might equal Marie. I’ll give it a shot.” I’m going to do something totally different, or I’ll just do what she did. I’m just trying to embrace the memory of her, and the joy that I got from it. So stepping into her shoes helps me symbolically with all of that. And her shoes are nice.

ZB: So then, the follow-up question is: After seeing the original production, has it been hard for you to create your own version?

AO: Yes. It’s difficult because of the way Martin’s work has to be rehearsed. You don’t get to do the scene over and over from start to finish without stopping. I have no idea who is developing in me until we start running the show. And then I’ll start getting the sense of who this person is. At the moment, it’s very much stop, start, stop, start, which is not conducive for me anyway. I tend to work through moods and energy shifts. I’m not getting the sense of that, which is not a problem. I’m very curious as to who’s going to appear.

ZB: What excites you about audiences seeing this today, 20 years later? What continues to be relevant?

A: Well, I think I love the universality of his darkness in relationships. I love that he puts it out there. It’s impossible not to recognize yourself in these desperate, almost psychopathic relationships.

For me, the play would be about owning your own power, or that if anyone ever encroaches on that space, you have to fight very hard to protect it. You’re in big trouble if anyone masters you — and I’m speaking here about the mother-daughter relationship. You’re in big trouble because you have no power. You’ve lost your own. And dark things can happen from that kind of powerlessness.

ZB: How do you think American audiences will respond to seeing this Irish play?

AO: I don’t know. I performed in front of an audience in America for the first time last year. And it was a very strange and scary experience for me because I’have spent 20 years performing to mostly English and Irish audiences. I can read them. If you get to know a species of audience, you can read them and you know how to play them. But with the American audiences, I had no idea of your taste and your comedy. It was a very interesting experience for me because it was unique. It was a totally different culture. I’m very interested in learning more about that. About how you respond, what’s your funny bone? What things move you?

ZB: In the play, do you have a particular scene, or a moment, or a line that you feel resonates the most with you?

AO: Not yet, but I love the humility, and honesty, and gentleness in a lot of these characters. They drop in these little, gentle sentences, and I think they are gorgeous moments for me to hear, as a performer in it, anyway. That it isn’t just razor-sharp.

ZB: How do you find the love in such a dark play? Do you think it is there?

AO: Definitely. It’s a funny thing that deep love can exist with masses of irritation. I irritate people too, I know that. As you get older, it’s less of a big deal. I’d be horrified to think I was capable of irritating anyone or boring anyone when I was younger, but now I’ve accepted that about myself. I think it’s all over the place.

ZB: Do you have a certain routine that you use to prepare for every role, or does it differ for each production?

AO: I don’t, but I’ll tell you what happened. I have been very instinctive until fairly recently, in that I would come completely open and unprepared to the first day of rehearsal. That was the way I worked and great things could come because I hadn’t made any decisions. Well, I worked on my first Shakespeare with this company last year. I was playing a fairly major part, and I’d never spoken a word of Shakespeare in my life.

I turned up one day, one big Bambi in the forest and the tiger Shakespeare stepped out of the trees. I was pretty much on stage for five hours speaking pure poetry and not understanding it. That was a baptism of fire, and since then, I try to come as prepared as I can be, in terms of learning the lines. I don’t have them off, but I know where they’re going, and then I come into the rehearsal space having done a bit of work. I think that makes me feel much more like an artist.

People who have gone to drama school are horrified listening to me going, “What? No preparation at all?” [Laughs]

ZB: So, there is a fine line between coming prepared and knowing enough, but not knowing too much, so that you can still discover.

AO: Yes. I think if you come in with some ideas, your mind has worked enough on it that you can change course. But if you come in with no ideas, you’re just going to accept the ideas that come to you. I think the crucial bit for me is to love the character. Even if you’re playing a psycho, to find something that you love.

ZB: That’s a good lead into my next question. With which parts of Maureen do you feel you identify?

AO: I identify with the weakness in her, the self-doubt, the way she tries to protect herself in her relationships. I see so much of me, and so much humanity, in her. That’s what is so brilliant about the play. Martin McDonagh was so young when he wrote it, and he just hit the seam of something about human beings that doesn’t often get shown.

Druid Theatre Company returns to Ann Arbor with a new production of Martin McDonagh’s dark comedy The Beauty Queen of Leenane on March 9-11, 2017.

Artist Chat: The TEAM

We had a lovely chat with Kristen Sieh (Teddy Roosevelt) and Libby King (Elvis) of the TEAM. RoosevElvis is in Ann Arbor September 29-October 1, 2016.

Twitter Chat with Artists: The TEAM

Join us for a Q&A with members of The TEAM. Once described as “Gertrude Stein meets MTV,” the TEAM’s work crashes American history and mythology into modern stories that illuminate the current moment.

Twitter Chat: Follow @UMSNews on Tuesday, September 27 at 4:30 – 5 pm.

RoosevElvis. Photo by Sue Kessler.

We’re very excited to present The TEAM’s RoosevElvis Thursday, September 29- Saturday, October 1. Take a hallucinatory road trip with the spirits of Elvis Presley and Theodore Roosevelt, who battle over the soul of Ann, a painfully shy meat-processing plant worker, and what kind of man — or woman — Ann should become.

Did you miss it? Here’s what happened.

Conversation: Young Jean Lee

Described by the New York Times as “the most adventurous downtown playwright of her generation,” Young Jean Lee is a theater maker with range. Her works Straight White Men and Untitled Feminist Show both explore gender and identity but in very different ways.

Holly Hughes (U-M professor, School of Art & Design and Department of Theatre and Drama) and Tina Satter (U-M Playwright-in-Residence) chat about what’s exciting, provocative, and interesting about these performances.

Transcription of conversation

Holly Hughes: I think it’s really exciting that UMS is bringing in Young Jean Lee because we’re not in a major metropolitan area where there’s a lot of contemporary new theater happening. And she’s definitely one of the more exciting and prolific voices that’s making avant-garde theater today, she’s a woman, she’s a person of color, and she’s working within an experimental but accessible domain, and there’s nudity. So it’s January and I feel like that’s going to heat things up a little bit; I’m excited about that.

Tina Satter: It’s so incredible to see that a play or performance is naked women on stage grappling with deep ideas. That a play called Straight White Men written in the traditional way of a well made aristotelian play is actually slowly cutting away at what that means and asking deeply contemporary questions of straight white male identity.

HH: You definitely should see both because it does speak to one of her gifts which is her range. And if you see one and you think that’s who she is, the other one just seems very different.

TS: You haven’t seen Straight White Men, right?

HH: I’ve seen so many straight white men; that’s all I see is straight white men!

TS: In a way like Destroy the Audience, the title alone in 2014, to call a show Straight White Men, that’s provocative just right there to call it that; it’s already doing so much work. Sometimes it’s like, “how dare she?” We don’t need any more straight white men, but we know she’s definitely going to be playing with that.

HH: Calling something Straight White Men after a whole engagement around identity politics makes us aware in a way that sometimes falls out of the conversation that heterosexuality, whiteness, maleness, those are all performances too; They’re all identities and they’re not just, “the culture”. It’s so rare for women to be allowed to be provocateurs, to really throw people into this level of discomfort and uncertainty. There’s a long tradition of men in culture, white men in culture being provocative and if they’re in fact not really provocative but just offensive, they can always hide behind that role. But with women it’s rare.

TS: I can’t remove the idea of Young Jean Lee’s emotional connection to the project. That’s something that’s always in my head when I leave her work.

HH: Can you say more about that?

TS: Maybe it starts because I’ve literally been on Facebook and I read her emotional connection to it from potentially a couple of years before. And it’s sometimes in a discomforting way, like she’s in there almost in my brain wanting to trigger something in me, in a way I don’t feel in many plays. Even plays that are made from a writer/director and they apparently have a more “hand of the maker” in them; That’s something I have when I leave those shows. What is a straight white man supposed to do with himself? Which actually is a question of the play and then, what is everyone that is not a straight white man also supposed so do with straight white men? Those are huge questions and I think it’s not like she’s even attempting to answer that, but those are underneath that, I think in that play. What does it mean in this contemporary moment to be a straight white man? And I think she’s pulling back to consider that in this antithetically subversive way by putting them in the most natural environment of a well made play about straight white men. I think it becomes a bit of a theatrical laboratory for considering.

HH: I think in Untitled Feminist Show you’re thinking about, or she’s wanting you to think about, when you talk about the performance of gender we’re talking about a kind of choreography of moving through and how your gender presentation informs the way you occupy space and how you do different daily tasks, banal tasks or not banal tasks but a range of tasks; How do you use your body? So if it’s a performance and there’s a kind of choreography for it, and by having different bodies on stage who have a different relationship to biology and different relationships to how they see their gender, she’s really thinking about it as a performance; It’s not an idea. It’s not some theory that somebody dreamt up; it’s a reality. To say gender’s a performance is a statement of fact. You’re really made aware of that. In a different way, using a different forum she’s also thinking about these identities we just thought of like, white people don’t have race, men don’t have gender and now we know that’s not true. I think she’s asking us to think and to feel about that and to not come to a conclusion. That’s different than writing a scholarly paper where you have to have some conclusion, even if it’s an open ended one you’ve got to wind it down.

TS: Yeah, I think the word you just used “to feel, to think and to feel” I think that ties into that thing I was trying to explain about Young Jean’s emotional questions that I somehow can feel present in me afterwards. I think getting to feel this thing unfold in front of you is a huge part of it. As clear as the topics are, from the titles to what you see, it’s not to stir up didactic answers; It is to stay with these questions and feel how confusing, and amazing, and scary it is to be next to these questions in a way that frankly only live performance can make happen to elicit a certain feeling.

See Straight White Men and Untitled Feminist Show in Ann Arbor January 21-23, 2016.

Artist Spotlight: Theater maker Rob Drummond

Editor’s note: Theater maker Rob Drummond’s Bullet Catch was part of UMS’s 2014-15 season. He returned this season for an extended educational residency, a collaborative effort between the University of Michigan’s Medical Arts program and UMS’s educational programs at U-M. As part of the residency, Rob is researching for a new play related to medicine. We asked him to write about his adventures in Ann Arbor.

November 6

I left the flat this morning at 4:30 am. I have not slept. And now the border control guy is doing his job. That’s all he’s doing. His job. Don’t blame him. Don’t get angry. That will only make things worse. I’m sitting in ‘the room.’ I’ve seen other people brought here but they were (borderline racism alert) not white, middle class, English speaking Brits like me. There’s an Asian woman sitting near me who looks on the brink of tears. As people in ‘the room’ often look. As I most likely look. I have tried to explain what I am doing over here.

Well, one thing I’m doing is running theater workshops for medical students.

The border control guy stares at me for around five seconds, like a dog trying to lip-read. And then replies …

Why?

Hmmm. How to explain my practice of cross-disciplinary, immersive artwork in one ‘get you across the border safely’ soundbite. Apparently, it can’t be done. So now I’m in ‘the room.’ And he’s on the phone to Mary Roeder, UMS Manager of Community Engagement, whose number I have got from the laptop that currently has 6% battery left. The laptop that has all the information about my stay here on it. And my adapter is in my suitcase. If that battery dies, then so do I. A bone-fide ticking clock drama on my hands here.

The longest three minutes of my life pass by before Mary calls back. She seemed to say the right things, and before I know it Officer Crocker was escorting me out of ‘the room’ and back into the airport. I hate Officer Crocker. Not because he was just doing his job. But because he did it with such grim authority. He is everything, I think, that the arts are not. He is the reason I make art. The world needs less of him.

November 7

If America were a person, I’d recommend psychiatric help. This was my first thought upon walking into the stadium where one hundred and eight thousand people had gathered to watch college kids playing football. Pure theater. My second thought. I used to play rugby at a decent level for my college. I remember the time we had forty people show up to a game and spoke of it for years to come. Everything is bigger in America.

November 9

I got a look at the Kevorkian papers today. Incredible collection, and something I would not have been able to access without this residency. I didn’t realize Kevorkian was an artist as well as a doctor. As well as a murderer. But was he? Or did he just help desperate people to do something they couldn’t do themselves? His name is certainly whispered as that of some sort of a boogie-man figure, but reading through the letters of his patients, I couldn’t help but feel that he was doing some important work in a controversial way. He was certainly challenging the status quo. Challenging conventional notions of morality. And he certainly had confidence in his convictions. I couldn’t help but like him. But maybe I am romanticizing him. Much much more research is required before I can begin work on anything that is even remotely like Kevorkian, the Musical, as my fevered imagination had already titled the project I had, before today, never even considered working on.

In the afternoon I visit a patient presentation class, which plays out remarkably like a play. We are introduced to the main character, a real life patient, who reminds me slightly of Woody Allen, and then we are invited to re-visit his experience in being diagnosed with a mystery illness. I am trying my best to guess along with the students (incredibly intelligent, all) and, thanks to many many hours of watching medical dramas, I manage (in my head, I don’t dare raise my hand) to follow the case and even make some sensible assumptions. I am struck with an idea that I must speak to Joel Howell (U-M Professor ad doctor) about. Replacing an hour of lectures every term with a play which explores the medical and ethical dilemmas of a specific patient’s case. Sort of like this but more highly dramatized, using actors and performed in a theater (not that type). I need to stop having ideas for things I am not here specifically to work on.

In the evening my mind turns fully to the reason I am here. Interviewing medical students and doctors about their experiences. I am writing a play for the Royal Court Theatre in London, and I think Act Two will be a verbatim piece using the testimonies of said medics and, more specifically, the topic if delivering bad news. It fascinates me as a dramatist that these people spend so much time surrounded by death and yet seem so well-adjusted. Perhaps it is precisely because they spend so much time in and around the thing that the rest of us try to avoid that makes them so well-adjusted. Or perhaps they are not as well-adjusted as I think. As the interviews commence, I realize that it is a combination of the two. It also strikes me that perhaps medical students are the only group of people who think about death as much as artists do.

November 10

What I was finding hard to explain to Officer Crocker is that when I make a piece of theater, I often like to immerse myself in the world so that I can feel more authoritative when I write about it. I have trained as a magician (the show which originally brought me to Ann Arbor and started this whole crazy love affair), a wrestler, and a dancer for shows in the past, and now was the time to experience just a fraction of what medical students and doctors experience by accompanying Dr. Scally on trauma rounds.

I get up at half-past ridiculous and make my way to the hospital. Which is like a small city. Feeling deeply intimidated and scared, I change into a set of scrubs. You can probably see in the photo below the mixture of fear and tired I was experiencing at this point. And then, as if I had always been a part of the team, as if it was the most natural thing in the world, I accompany two doctors, a resident, and a student (I think I’ve got that right) on rounds. Confidentiality precludes my mentioning anything specific but suffice to say it was an eye opening experience, my major take away being the feeling that doctors absolutely have to develop a dark sense of humor to get them through the day. They have to.

November 12

I have done a few workshops by this point and something that has struck me is that there really is little difference between the artists and the medical students. Whether it be improvisation, writing, or performing, they all enter into it with the same vigor. Both groups offer up insightful and interesting suggestions. Both are equally uncomfortable standing silently in front of the rest of the group. All the workshops are more or less effortless to deliver because the students are so…bright. One group came up with a brilliant play that was set at the top of the Empire State Building during its construction. Four workers on a metal beam, as in that famous photograph. In one-and-a-half hours together we fleshed out this idea, made it real. When I left, one of the students was sitting and writing in the hall. She said she had started writing the play we had just created. I was pleased. I went out and ate some food. Drank far too much beer (Apparently the Hop Cat loves a British accent). And when I came home again around half eleven…She was still there. Still writing.

It might have been the beer, but that made me choke up a little.

November 16

Really getting to know and like the people who are showing me such great hospitality while I am here. The interviews are going so well — getting so much incredible material. The students and doctors alike are amazingly open, to the extent that I am starting to feel guilty about milking them for their stories of misery. However, what has been coming out of this is the understanding that they are anything but miserable despite the fact they are surrounded by so much of it. They are doing a good thing with their lives. The delivery of bad information is not enjoyable, but the fact that they take part in such vital conversations, perhaps the most vital you will ever have, fills many of them with a kind of satisfaction. It’s a privilege. That’s a phrase I’m hearing a lot. It’s a privilege to be trusted with such a sensitive moment in a person’s life. To be sharing something real. Again, a massive similarity between artists and doctors presents itself. We are both looking for something real. We are both searching for truth. In many different ways.

November 17

I had a rip-roaring time at a trivia night last night (the only thing we won was an over-sized Miller Lite T-shirt which my wife is now wearing as a night-gown), but I was a good boy and didn’t drink too much as I knew I had to be up for another set of rounds, this time internal medicine, with Dr. Fine. As the picture below might suggest, this set of rounds did not require me to wear scrubs, so I felt a little less awkward. Again, I was welcomed into the fold as if I was just another medical student. The patients, I realized, didn’t have a clue that I wasn’t some world leading expert in something, which actually made me relax a little bit. Little did they know I was actually a nervous, anxiety ridden, socially awkward wreck. But actually, from the interviews I have conducted, I have come to realize that this is the normal way for a student to feel in a hospital.

These rounds are different. Less immediate danger. But more emotional somehow as the patients stories can be delved into in more detail. I come out feeling my respect for doctors deepen still. Dr. Fine genuinely cares about his patients. He cares not only about making them physically better but making sure they are emotionally cared for.

November 18

Another session with the Kevorkian papers is followed by my last workshop. We seem to save the best for last as together we come up with a concept for a play and create another world in an hour-and-a-half. This is the story of a young offender in prison. The twist is we never see her face. We only hear her voice and we learn about her through the visitors she receives. A really genuinely exciting concept created from nothing and fleshed out with characters, a plot line, and a question we collectively try to answer. What Price Truth? I’ve capitalized that question because it also works as the title. What is the truth worth? Should the girl lie for a reduced sentence or keep telling the truth and get life? Should we tell the difficult truths or lie for an easier life?

This cuts to the heart of the play I am working on for the Court. How do you tell someone they are going to die? Do you sugar coat or do you tell them the cold hard truth? Is it ever right to withhold information from a patient to spare their feelings? What Price Truth?

A good way to end my stay.

November 19

I left Michigan yesterday evening. And now I’m going through customs at Glasg-. Oh. I’m through. He barely looked at my passport. The joys of returning to your home country as a national. On my way though, I see a passenger has been taken aside (we don’t have the budget for a whole room apparently) and is being questioned. He doesn’t speak much English – he’s dark-skinned, possibly Indian, I’m not sure. The difference? This time the border control people are smiling. Joking with him. Trying to put him at ease. We’ll get this sorted. Don’t worry.

You see that Officer Crocker. That’s how you do it.

Rob Drummond is a writer, performer and director from Glasgow. His theater credits include Sixteen (Arches Theatre Festival), Hunter (National Theatre of Scotland and Frantic Assembly), Mr Write (Tron Theatre and the National Theatre of Scotland), and Rob Drummond: Wrestling (The Arches, winner of a Vital Spark Award), among others.

Interview: Theater maker Young Jean Lee

Moments in Untitled Feminist show (left) and Straight White Men (right). Photos by Julieta Cervantes and Brian Mediana.

“Young Jean Lee is, hands down, the most adventurous downtown playwright of her generation.” (New York Times) This January, UMS showcases Young Jean Lee’s two most recent theater works on gender and identity. The plays are performed across the street from each other in the Power Center and Lydia Mendelssohn Theatre.

UMS Lobby regular contributor Leslie Stainton interviewed Young Jean Lee ahead of the visit.

Leslie Stainton: How do you define “theater”?

Young Jean Lee: I don’t have a definition for it. If someone calls it “theater,” then to me it’s theater.

To my knowledge, this will be the first time anyone’s deliberately paired Untitled Feminist Show with Straight White Men. What do you hope happens from that juxtaposition? What are you most curious about?

The shows are so different and appeal to such different audiences, but for me they’re both coming from a similar place. My hope is that seeing them back to back will encourage audiences to look for their similarities.

How do you go about choosing a language—verbal, nonverbal—for a specific work about a particular topic?

I’m always trying to find the best match between form and content. For the first workshop of Untitled Feminist Show in 2010 I wrote a script and after the showing, our audience did nothing but make academic arguments about feminism. I wanted to hit people on a more emotional, visceral level, so as we did more workshops, I kept cutting out more and more of the text until there was nothing left but movement, and the audience was forced to react emotionally. I tried hard to write words that could compete with the movement and dance, but I couldn’t. We found that movement communicated what we wanted much more strongly than words did

For Straight White Men, I saw the traditional three-act structure as the “straight white male” of theatrical forms, or the form that has historically been used to present straight white male narratives as universal. And I thought it would be interesting to explore the boundaries of that form at the same time as its content.

What role do you see for live performance in our technological age? In what ways, if any, must live performance evolve and/or adapt in a world of rapid technological change?

Theater has been around forever—it’s survived the advent of radio and television and film. It’s become part of our educational system. I don’t really see it going anywhere.

What issues are you yearning to tackle in your work (or not, given your penchant for writing about “the last thing” you’d want to write about!)?

The Native American genocide has been on my mind a lot lately.

What are you working on now?

I’m trying to figure out how to make my first feature film!

When did you first fall for live performance?

There was a summer stock theater in the town where I grew up, and my parents took me to see A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum when I was very young, and I was hooked.

Many of your pieces deal with identity. In what ways is theater especially well suited for addressing questions of identity?

I don’t know that it is. Identity is hard to address in any art form, I think.

What key trends do you see in American theater today?

I think that contemporary American theater is very aesthetically conservative, and that it charges way too much for tickets. It isn’t adventurous or challenging enough — I’m thinking of mainstream commercial theater where everything has a linear plot line and there’s very little formal experimentation. I think the New York experimental theater/performance scene is still exciting. The stronger artists tend to have longer developmental processes. The performers have a lot of charisma and intelligence. There’s a lot of collaboration. On the other hand, I think a danger with experimental theater is when it gets locked into its own kind of tradition and you just see a bunch of experimental-theater cliches being played out.

See Young Jean Lee’s Straight White Men and Untitled Feminist Show in Ann Arbor January 21-23, 2016.

UMS Artists in Residence: Meet Andrew Morton

Editor’s note: UMS is in the second season of its Artists in “Residence” program. Five residents from across disciplines take residence at our performances throughout our season. We’ll profile each resident here on UMS Lobby.

Andrew Morton’s plays include Bloom (a winner at the 2013 Write Now Festival and winner of the 2013 Aurand Harris Memorial Playwriting Award), which received its world premiere at Flint Youth Theatre in May 2014 and was subsequently published by Dramatic Publishing, Inc. Other works include: February (shortlisted for the 2007 Royal Court Young Writers Festival), Drive-Thru Nativity, and the collaborative projects State of Emergency, EMBERS: The Flint Fires Verbatim Theatre Project, and the upcoming The Most [Blank] City in America, premiering at Flint Youth Theatre in April 2016. As a community artist and educator, Morton has worked with a range of organizations across the globe, including working alongside Salvation Army community counselors in Kenya to incorporate participatory theatre into their work with people living with HIV/AIDS. While based in the UK, he worked with several educational theatre companies and was the Education Officer at the Blue Elephant Theatre where he ran the Young People’s Theatre and the Speak Out! Forum Theatre projects. Morton is currently based in Flint, Michigan where he teaches at the University of Michigan-Flint and is Playwright-in-Residence at Flint Youth Theatre.

UMS: Tell us a little about yourself and your background in the Arts.

Andrew Morton: I was born in Derby, England, but moved to Michigan with my family when I was 12 years old. I was raised in a family full of musicians, but as a teenager I became more interested in theater. I studied theater as a undergrad and like most who follow that path, I originally thought I wanted to be an actor. However once I began to explore writing more I realized that was what I really wanted to do. I moved back to the UK in 2004, and then spent six years in London. During that time I was part of the Young Writers Program at the Royal Court Theatre, which I now consider to be one of the most valuable experiences in my artistic journey. I also got my Masters of Arts in Community Arts from Goldsmiths College, which was also incredibly influential on my practice as a theater maker. For a few years I ran several youth theater projects at the Blue Elephant Theatre in Camberwell, South London, and in 2010 I came back to Michigan. Since then I’ve been living in Flint, where I teach theater at UM-Flint and am Playwright-In-Residence at Flint Youth Theatre.

Andrew Morton: I was born in Derby, England, but moved to Michigan with my family when I was 12 years old. I was raised in a family full of musicians, but as a teenager I became more interested in theater. I studied theater as a undergrad and like most who follow that path, I originally thought I wanted to be an actor. However once I began to explore writing more I realized that was what I really wanted to do. I moved back to the UK in 2004, and then spent six years in London. During that time I was part of the Young Writers Program at the Royal Court Theatre, which I now consider to be one of the most valuable experiences in my artistic journey. I also got my Masters of Arts in Community Arts from Goldsmiths College, which was also incredibly influential on my practice as a theater maker. For a few years I ran several youth theater projects at the Blue Elephant Theatre in Camberwell, South London, and in 2010 I came back to Michigan. Since then I’ve been living in Flint, where I teach theater at UM-Flint and am Playwright-In-Residence at Flint Youth Theatre.

UMS: Can you tell us a little about your creative process? Where can we find you working on your art?

AM: I describe a lot of my work as “community-based”, so while occasionally I’ll be writing at home or at the Good Beans Cafe (hands down the best coffee shop in Flint), I also spend a lot of my time out and about talking and listening to people, or facilitating conversations that will inform the work I’m creating. I’m currently developing a new play for Flint Youth Theatre called The Most [Blank] City in America, which is inspired in part by the constant negative press that the city receives. As we want the play to represent a wide range of opinions on Flint and help challenge the dominant narrative of the city being a violent and depressing place, I’ve been working with a team of local artists to engage a wide range of community groups and individuals and listen to their stories about living in Flint. We’ve had conversations in music venues, schools, parks, and are just about to start a second round of these in the fall. The play will be produced at Flint Youth Theatre in April next year, so our challenge is to try and include as many stories and voices as we can in the final piece.

UMS: What inspires your art? Can you tell us about something you came across lately (writing, video, article, piece of art) that we should check out too?

AM: When I’m not working on a project I try to read plays and see live theater as much as I can, but I also enjoy a variety of art forms and try to experience different forms whenever I can. I love live music, and since I lived in London I’ve also become more appreciative of dance and physical theater. I’m always impressed by work that can tell a story without relying on words. Earlier this summer I saw one of the events by performance artist Nick Cave, who currently has an exhibition Here Hear at Cranbrook Museum. The event I saw was a performance at the Dequindre Cut in Detroit. It was a fantastic collaboration between the artist and several local groups, and I’m looking forward to his other performances later this year.

UMS: Are you engaged with the local arts community? Tell us about groups or events that we should know about.

AM: I love the arts community in Flint, and Flint as a place is a constant source of inspiration in my work. In addition to a amazing Cultural Center (with the Flint Institute of Arts, the Flint Institute of Music, the Whiting Auditorium, and more), Flint is home to many artists, performance groups and organizations who do some incredible work in the community and are getting national recognition. Sadly I think many people in Michigan aren’t aware of the rich artistic scene in Flint as we’re often overshadowed by places like Detroit and Grand Rapids, but I hope that’s starting to change. Flint is home to Raise it Up! Youth Arts & Awareness (who have an amazing youth poetry team), Tapology (a fantastic tap dance group), and The Flint Local 432 (an all-ages punk rock and multi-arts venue that is just about to celebrate it’s 30th birthday). Tunde Olaniran is a Flint-based musician who is blowing up right now, and is getting a lot of national press for his latest album, Transgressor. Of course, I have to mention my artistic home, Flint Youth Theatre. Unfortunately I think a lot of older people are put off by the word “youth” in our name, but the work we create is for audiences of all ages, and is consistently of a high professional quality. We produce both well-known plays and new works, and if you’ve never seen one of our productions you are missing out! Our next production is Little Women, which runs Oct 10-25.

UMS: Which performances are you most excited about this season and why?

AM: Honestly, I’m excited about them all. I saw Ivo van Hove’s A View from the Bridge at the Young Vic in London last year and it blew me away, so I’m excited to see what he does with Antigone. Young Jean Lee and Taylor Mac are two theater artists I’ve been following for a while now, but I’ve yet to see work by either of them. I think they are two of the most exciting voices in American Theater right now, so I’m thankful to UMS for bringing them to Michigan.

UMS: Anything else you’d like to say?

AM: I think I’ve said enough already… 🙂

Interested in more? Watch for more artist profiles on UMS Lobby throughout this week.

The State of Theater in Ann Arbor: Looking Back to 2000, and Looking Ahead

Editor’s note: This article initially appeared in the Ann Arbor Observer in October 2000 and offers a snapshot of the history of theater in Ann Arbor and major developments in the city’s theater life during this time.

Leslie Stainton is a regular contributor to UMS Lobby, focusing on theater. Her new book Staging Ground captures the history of one of America’s oldest and most ghosted theaters—the Fulton Theatre in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

She participates in an authors panel on January 28, 2015, which also included U-M faculty Martin Walsh and Leigh Woods. While the panel will spotlight Staging Ground, it will also provide an updated look at the state of theater in Ann Arbor today.

We thought this “time capsule” would be a great read ahead of that panel.

Arthur Miller, Lee Bollinger, and the U-M’s dead-serious campaign to bring Ann Arbor back to the theatrical big leagues.

It’s been nearly sixty-five years since Arthur Miller sat in a rented room at 411 North State Street in Ann Arbor and in six days wrote his first play. That work, No Villain, won Miller a Hopwood Award worth $250—half the sum it had cost him to come to Michigan in the first place—and convinced him he had what it took to compete with the reigning Broadway playwrights of his day: people like Clifford Odets, Maxwell Anderson, and Philip Barry.

Today, of course, Miller’s name outshines all the rest. “He’s the greatest living American playwright,” says U-M English prof Enoch Brater. With Eugene O’Neill and Tennessee Williams, Miller created the plays that became the bedrock of American theater. His best-known work, Death of a Salesman, has been performed around the world. Last year’s Broadway revival won four Tony Awards half a century after the play premiered in 1949.

Arthur Miller returns to Ann Arbor this month to give the keynote address at an international symposium honoring him on his eighty-fifth birthday. It’s an auspicious moment in the American theater, nationally as well as locally.

An Up and Down Track Record in Ann Arbor

From New York to California, the commercial stage is thriving. For the first time in years, thanks to a booming economy, every theater on both Broadway and Off Broadway is lit. Big musicals earn huge grosses in New York and spawn profitable touring productions that play to packed houses in places like Toronto and Detroit. Nonprofit theater attendance across the country is also up, according to a 1999 survey by the New York–based Theater Communications Group, as are artist salaries, education and outreach programs, and individual giving. But the costs of producing theater are higher than ever, and competition for arts funding is fierce.