Interview: Tiffany Ng, University of Michigan Carillonist

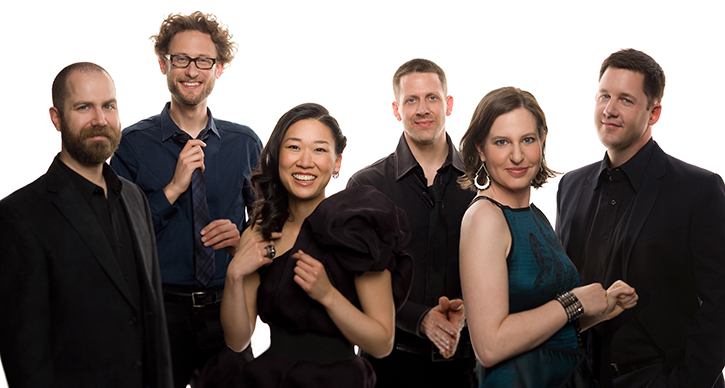

On November 7, 2017, the China NCPA Orchestra make their UMS debut in a performance that also features pipa virtuoso Wu Man. Tiffany Ng is an assistant professor of music at the School of Music, Theatre & Dance and the University carillonist at Burton Tower. Her research focuses on the spectator and employee culture of the National Center for the Performing Arts venue, and we chatted about role of Western classical music in contemporary Chinese culture, bringing kids to concerts, seeing the orchestra in Ann Arbor, and more.

On November 7, 2017, the China NCPA Orchestra make their UMS debut in a performance that also features pipa virtuoso Wu Man. Tiffany Ng is an assistant professor of music at the School of Music, Theatre & Dance and the University carillonist at Burton Tower. Her research focuses on the spectator and employee culture of the National Center for the Performing Arts venue, and we chatted about role of Western classical music in contemporary Chinese culture, bringing kids to concerts, seeing the orchestra in Ann Arbor, and more.

You mentioned that your research was focused on the spectator and employee culture of the National Center for the Performing Arts venue. What surprised you about the culture of the venue? What did you learn more broadly?

In the fifteen or so years following the construction of the groundbreaking Shanghai Grand Theater in 1998, every first-tier, second-tier, and even aspiring third-tier city in China has striven to demonstrate its global modernity with an architecturally adventurous cultural building. The new performing arts centers are designed to showcase a variety of traditions, from Western opera to Chinese theater to Russian ballet. It’s remarkable to see classical music playing such a prominent role in the nation’s construction of global cosmopolitan cities. The powerful association of Western classical music with a new sense of Chinese global modernity has drawn new audiences of all ages to classical music concerts. The single most important listeners, from my point of view, are children.

During the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), conservatories were closed, and Western classical music was banned and its practitioners persecuted. The result is that an entire generation shares an unfamiliarity with that tradition. By 2009, however, an estimated 38 million children were studying piano, supported by parents whose hopes for their children range from gaining an edge in college admissions to international music stardom. In my fieldwork at Chinese performing arts centers, I regularly observed that concerts are filled with earnest parents whose children listen quietly and attentively to solo pianists and symphony orchestras alike. I would warn, however, against the sweeping statements going around that China is to become the refuge of Western classical music as Western audiences dwindle. There are new audiences being cultivated in Western countries, and new Chinese traditions being cultivated in Chinese performing arts centers.

that an entire generation shares an unfamiliarity with that tradition. By 2009, however, an estimated 38 million children were studying piano, supported by parents whose hopes for their children range from gaining an edge in college admissions to international music stardom. In my fieldwork at Chinese performing arts centers, I regularly observed that concerts are filled with earnest parents whose children listen quietly and attentively to solo pianists and symphony orchestras alike. I would warn, however, against the sweeping statements going around that China is to become the refuge of Western classical music as Western audiences dwindle. There are new audiences being cultivated in Western countries, and new Chinese traditions being cultivated in Chinese performing arts centers.

Anything that you learned that you think would be interesting or useful for an Ann Arbor audience member attending the performance to consider?

Bring your kids! Given the educational value that families in Beijing place on taking their children to symphony concerts at the National Center for the Performing Arts, the members of the NCPA Orchestra are seasoned at performing for audiences of all ages. I’ve seen Chinese orchestras play on unfazed, even as the occasional child listener vocalizes delight or scrambles over seats to get closer to mom or dad. The NCPA Orchestra is a leading force in building new, young generations of classical music fans in Beijing.

The NCPA Orchestra is visiting Ann Arbor in November. Will your research impact how you experience the performance?

Absolutely. Many audience members in China are unfamiliar with, or just not invested in, current Western concert-going orthodoxies; for example, there are usually a few listeners eagerly snapping mobile phone photos and videos during classical concerts so they can share the excitement of the experience with their friends. This will be my first opportunity to see the NCPA Orchestra perform outside of China to audiences with a more uniform social code. Moreover, the repertoire of symphony orchestras in China can be subject to the agendas of state and corporate entities and to the NCPA’s mission to foster greater classical music literacy in China, but this performance will stage the NCPA’s self-presentation to American audiences. I’m excited to see how the NCPA approaches the opportunity to help Western audiences learn more about China’s burgeoning classical music scene and its global connections.

Absolutely. Many audience members in China are unfamiliar with, or just not invested in, current Western concert-going orthodoxies; for example, there are usually a few listeners eagerly snapping mobile phone photos and videos during classical concerts so they can share the excitement of the experience with their friends. This will be my first opportunity to see the NCPA Orchestra perform outside of China to audiences with a more uniform social code. Moreover, the repertoire of symphony orchestras in China can be subject to the agendas of state and corporate entities and to the NCPA’s mission to foster greater classical music literacy in China, but this performance will stage the NCPA’s self-presentation to American audiences. I’m excited to see how the NCPA approaches the opportunity to help Western audiences learn more about China’s burgeoning classical music scene and its global connections.

Where are you with your research now, and what are your future research plans?

Next year, I plan to return to Beijing and Shanghai to do follow-up fieldwork, supported by the Confucius Institute at the University of Michigan. Besides looking for the latest developments in audience behavior and demographics, I’d like to investigate the associations of Western classical music with nature, a connection that my interviewees frequently mentioned. I’d also like to conduct a more focused investigation of the developing role of concert hall pipe organs in China. When I first visited, the role and use of those numerous new instruments was unclear, and is evolving rapidly even now, along with the completion of China’s first carillon in Beijing in 2014. I’m Assistant Professor of Carillon in the Organ Department, so the development of these instruments in China is of great interest to me as a practicing musician.

See the China NCPA Orchestra at Hill Auditorium in Ann Arbor on November 7, 2017.

Interview: Jillian Walker, UMS Research Residency Artist

For the 2017-18 season, we are excited to welcome Jillian Walker as our Education and Community Engagement Research Residency Artist. The UMS ECE Research Residency provides time and resources for an artist to spend an extended period of time in Ann Arbor developing a new performance work. A graduate of University of Michigan (B.A.) and Columbia University (MFA), Jillian is an established and accomplished artist, dramaturg, playwright, writer, and activist.

During her time with UMS, Jillian will be developing her latest project, a play called Tignon, inspired by a late 18th century law in New Orleans that required women of color to wear a covering—called a tignon—on their heads to hide their hair. Through this project, Jillian hopes to use “this fascinating slice of legal truth as an intersectional site to explore sex, power, policy, religious practice, gender roles, race, and economy in one of the most interesting and still misunderstood American cities our complicated country has to offer.”

We chatted with Jillian about her writing process, decolonizing history, and returning to Ann Arbor.

Jillian Walker. Photo courtesy of the artist.

AT: How did you first come to hear about El Bando du Bierno, the law that required women to wear a Tignon?

JW: It was actually on a blog. I think it was Black Girl with Long Hair, which is a really popular blog. I got an article in my inbox about the law, and I was like: “This can’t be real.” So, I clicked on it and kept reading. I was so fascinated by the fact that this was actually a mandated law. So, I filed it away in my mind and didn’t do anything with it at first. But I held onto it and knew that I would return to it at some point.

AT: Do you feel that the act of coercing non-white women into covering their in 1786 hair instilled a sense of humiliation that women of color still feel today about their hair and overall appearance?

JT: I think that it definitely proves the point that hair has always been political for black women. If we can go all the way back to 1786 for evidence of that, I think that speaks very loudly to relevant cases today. But what I’m finding in my research and what I’m excited to investigate more with UMS, is that black women made the most of that law at the time. They made their wraps really elaborate and they said, “Okay, fine. If we have to cover our hair then it’s going to be in a fabulous way.” But I do think that even with that, it’s sort of impossible to not feel “less than,” and to not internalize the negative side of what happens when we mandate people’s bodies.

AT: You are already quite an accomplished artist and playwright! How do you think this work compares to your other works in terms of your writing process, inspiration, and goals?

JW: I think the main question that I ask in pretty much everything I make is, “How do we heal?” But, I think it will manifest very differently in Tignon. I’m basically constructing a language. I’m trying to see what women in the 1700’s sounded like. They’re living under Spanish rule at this time, so there is Spanish woven into a broken sort of English that is also very directly related to West Africa, because we’re talking about women who have just come from Africa 20 or 30 years before this. I’ve never tried to make a language before. But the thing that’s going to be the same is the deep investigation of whatever world I’m creating, and it usually happens through and in tandem with my own life.

AT: Can you tell me a little bit about the “Speculative Histories” workshop you’re offering in Ann Arbor on MLK day?

JW: The idea for the workshop really came out of this sense that as I was doing research about the edict of the government, and trying to learn more about New Orleans from the perspective of women of color. I had a lot of trouble, and one of the big reasons is that many of these women were illiterate and weren’t writing their stories down. So far, everything I’ve found is written by colonialists–white men at the time who were surveying New Orleans basically to see how viable it was to make money. Every once in a while they mention a black person, and that’s sort of how I’ve been finding information.

So, Speculative Histories is really about the importance of filling in the holes that are left in the narratives not constructed by people of color. This is a revolutionary act that we can all participate in, to imagine those histories, and bring those histories forward, and not just stop at, “Oh, well we don’t know. There’s nothing we can do.” I think this idea that you only get to tell the truth when you win (and in this case winning means access to language and the ability to tell your story in print) is a racist idea or at least a colonialist one. So how do we decolonize this idea of history? I think we do this by valuing imagination as much as we value fact, and by valuing art making and creation as much as we value the census, or whatever. I feel it’s always a really healing thing to go into an imagined space where I can just place myself into those circumstances and construct the truth out of it. So the workshop will be about that.

AT: What does it mean to you to be developing this piece with UMS and at your Alma Mater?

JW: *Does a happy dance* Woo! It means a lot! It feels full circle. The University of Michigan has one of the best libraries in the world that I didn’t take advantage of as an undergrad. Since leaving U-M, I’ve really fallen in love with research. The irony is not lost on me, that I ended up at Michigan, one of the best research institutions in the world, and then came to New York and went to Columbia, which is also a really incredible research institution. So I’m really excited about being back in Ann Arbor. I’m a proud Wolverine, always have been!

AT: What are you looking forward to most about the residency?

JW: I’m looking forward to what will be uncovered; what voices will be speaking. I think part of how I write is by listening, so I’m excited to have my ears open and all of my pores open and hear whatever strikes me.

Jillian Walker is the 2017-18 Education and Community Engagement Research Residency Artist. Her workshop Speculative Histories takes place on Monday, January 15 at 7 pm and is free and open to the public.

Interview: Matthew VanBesien and Ken Fischer

UMS welcomes Matthew VanBesien, seventh president of UMS. Learn more about Matthew in this joint interview with outgoing UMS president Ken Fischer. Jennifer Conlin moderates.

Part 1

Jennifer Conlin: I thought that we would start with how you met. I hear it is a meeting that did not occur in the hallowed halls of Hill Auditorium or at the Lincoln Center, but rather here at the University of Michigan Ross Business School.

Matthew VanBesien: That’s right.

Ken Fischer: You should talk about that.

Matthew: [laughs] Well, I think it was a great opportunity. I think I won the award for coming the farthest for that session here at Ross. I’d never been to the University of Michigan before, and coming to the Ross school with all these great colleagues, meeting Ken, meeting the wonderful people from the National Art Strategies, it made a real impression.

Ken and I met and we said to each other, “How is it that we’ve never met?” Because I knew all about UMS here. I know Ken’s brother, Norman Fisher, who teaches cello at Rice [University], at the Shepherd School of Music at Rice in Houston, where I used to live. I think we just made a connection immediately, I don’t know that I knew Ken was a horn player, but we sussed that out pretty quickly. Ken took me on a road late night to literally every performance venue on the University of Michigan campus but it was so clear what a special place this was and, of course, Ken is so effusive and wonderful about what happens here and why it’s so special.

Ken: So that’s where we first met.

Jennifer: Then, let’s talk about the [New York] Philharmonic Residency, because you also work together now and there you are with the oldest orchestra in the country and one of the oldest — Is UMS the oldest?

Ken: Well, the oldest of the university related presenters, at 138 years like you said. From Melbourne, Mathew came to the New York Philharmonic and of course, this is an orchestra that we love and that we’ve had coming here for a number of years. In 2013 they were here, where we had a chance, actually, to work together in building that program. Then, of course, the big residency of 2015 which had some really distinctive features. But in working together, of course, we are deepening that relationship; he’s getting to know a bit more about Ann Arbor and we are able to do some great things together.

Matthew: I remember, I was here for 2013, not too long after I started at the New York Philharmonic. The Philharmonic has been coming here, I think, 1916 was the first —

Ken: That’s right.

Matthew: That was before the New York Philharmonic had gone to Europe for really toured anywhere internationally, they were here in Ann Arbor, at Hill [Auditorium]. [In 2013,] I remember Ken took me to breakfast at Zingerman’s Roadhouse. So, it was important for me to understand this iconic landmarks here in Ann Arbor. The wheels started turning right there, and I started telling Ken about some of the orchestral training initiatives that we started, really trying to work intensively with young musicians to help them. Not just to understand how to play their instruments, they get a great education about that at a great conservatory, but the fine craft of orchestral playing.

So we thought, let’s think about a way to have a regular presence for the New York Philharmonic here in Ann Arbor, then to build a lot of rich activity around the main stage concert. I think, when we were here in 2015, we played three main stage concerts but we did 35 — I don’t want to call it ancillary in a smaller way, but really important events around that at the music school, across the university.

Jennifer: And at the halftime show. [laughs]

Matthew: [laughs] There was a halftime show.

Ken: Don’t you love that we have now a person who grew up in the Midwest but also went to a Big Ten school. Now it’s Indiana, they are generally better in swimming and basketball than in football. [laughs] But there was a sense of what can happen on game day.

Jennifer: We weren’t going to mention Indiana specifically.

Matthew: The brass players were thrilled about doing it. Alan Gilbert, our music director, conducted part of the show but it was amazing to see. I think it was about thousand musicians, the UMS Choral Union, the Michigan Marching Band, Alumni. To see a thousand musicians out there….It was just a very special moment.

Our players in New York still talk about this, this was really one of the most memorable things that they’ve done, and being a member of the New York Philharmonic you get to do some memorable things along the way. But that was incredibly special and I have a big photo in my office in New York that Ken and UMS sent to me. A special thing.

Ken: It was one of those things that really deepens your relationship between an ensemble presenting organization but especially the community. Imagine what we can do for the next residency in November 2017. It just happens to be approaching the centenary of Leonard Bernstein. A man who not only loved that orchestra, but boy did he love Ann Arbor and coming here. We’re going to remember Bernstein in a very special way.

Jennifer: It’s the Young People’s Concert.

Matthew: I think it’s great because it’s not just an entire homage to Lenny. It’s really a testimonial for all the things that he did. The opening concert will be with the incoming music director of the New York Philharmonic, Jaap van Zweden, who would never have even begun a conducting career had it not been for Leonard Bernstein who was then conducting the Concertgebouw, asked Jaap who was the concertmaster to conduct a little bit so he could go out into a concert hall and listened on a tour. Jaap had never even conducted before, and he’ll tell this story when he comes to Michigan this fall.

The Young People’s Concerts actually started in the 1920s in New York, but they were catapulted to this unbelievably iconic status in the 1950s with Leonard Bernstein because they were televised on CBS. Back when major networks televised something like the Young People’s Concert, and of course, Bernstein was on television a lot. Then, of course, we’re doing his music. We’re doing the third symphony, the Kaddish Symphony, which is an incredibly powerful work. It’s a great mix. Some of the things that we’ve talked about around the residency are also very, very exciting in terms of how they really engage students, how they engage the greater University of Michigan community, Ann Arbor community, and Southeast Michigan. It will be a lot of fun.

Jennifer: I hear as well that it was during the halftime show that you started even considering UMS.

Matthew: Rosie, my wife, had reminded me of a conversation that we’d had before we went to New York. That conversation was, “It’s such an amazing opportunity, we’re going to New York. I’m so happy for you to have this chance to work with the Philharmonic.” The discussion was, “What happens at some point when you’re not at the New York Philharmonic, what would that look like?” She never said a word during the entire process here for UMS. The day that I was announced as being Ken’s successor, she reminded me that we had this discussion. Apparently, I said, “You know what I think would be really great is to go to UMS and the University of Michigan after I finished with the New York Philharmonic.”

Jennifer: [laughs]

Matthew: I really gave her a hard time, because I was like, “I can’t believe you never mentioned this during all the last several months of going back and forth.” I do remember when we were here in 2015, Ken and I were walking to the stadium, the day of this great activity. I think Ken started saying, “I’m thinking about my future and possibly stepping down in a few years.” There’s no question in my mind that that planted the seed.

Ken: If that was a bug that was put into your ear at that time, I’m thrilled that it was because I hope you know how great I feel about having a friend, a colleague whom I highly respect in an ensemble that he has been leading that has more than 100-year affiliation with us. We both have Interlochen in our experience, which was for both of us a transformative experience. Then, my dear, we both play the French horn. I was just thrilled, yes.

Matthew: Well, for someone who’s looking at a position like this, I mean one of the things that really makes an impression is, who will be your predecessor and all that they’ve accomplished and the spirit. Ken has this unbelievable spirit of generosity. I mean, it’s unrivaled, I would say, in the performing arts. It means a lot to me to be able to come here and succeed him. Understanding that the incredible 30-year tenure that he’s had here and how much UMS has evolved into much, much more than an organization who presents concerts.

The evening before I was announced, I called a good colleague, Wynton Marsalis, and he went on and on about how much he loves UMS. He talks so much about how it’s not just about what’s on stage but what happens around the performances; going out into the community, engaging students at the university, engaging Ann Arbor, engaging Southeast Michigan. That’s the testament to the work that Ken has done here.

For me, it’s a real honor to be able to come here and succeed this guy because he is a great colleague, he is a great friend. I know what an amazing job he has done here. I consider it a great responsibility, a fun responsibility, to learn as much as I can from Ken during this transition period, but also, to really uphold the legacy that he has created.

Part 2

On Being African at the University of Michigan

Moment in portrait of myself as my father. Photo by Gennadi Novash.

Nora Chipaumire’s portrait of myself as my father is a piece of many origins. All aspects of Chipaumire’s identity as an African, a woman, a black woman, an African woman, and an African-American woman seep into her work. In this “love letter to black men,” she explores the complex tangle of conceptions, stereotypes, expectations, vulnerabilities and strengths of the black African male.

Zimbabwean influences, unique venue

A dizzying combination of Zimbabwean and African dance traditions, garb, and music help to tackle these big questions. Traditional Zimbabwean music rooted in polyrhythmic beats combines with Zimbabwean dance, an art form which requires a considerable amount of strength and agility to perform. Chipaumire uses these tools to celebrate the strength, resilience, and inherent defiance of the black body. She fuses her Zimbabwean heritage with her contemporary dance training to create this piece. Wearing traditional African gris-gris (a talisman used in Afro-Caribbean cultures for voodoo) with football pads, Chipaumire explores the black male at the crossroads of two cultures and identities.

Nora Chipaumire in portrait of myself as my father. Photo by Elise Fitte Duval.

The piece is set in a boxing ring and will be performed in at the Detroit Boxing Gym, where a program to support kids living in Detroit’s toughest neighborhoods is based and focuses on helping young black males find fruitful after-school activities to grow and develop real-life skills with positive role models.

It is not only a fitting location for Chipaumire’s exploration of black masculinity in a postcolonial world but also serves as a perfect setting for her vigorous, high-energy performance. Chipaumire has also spoken out about the brutal policing of black sexuality and masculinity, and celebrates her heritage through her art.

On Being African at the University of Michigan

African students at the University of Michigan have a unique perspective on the challenges and stereotypes Africans experience in America. Tochukwu Ndukwe, a Nigerian-American kinesiology student born in Nigeria and raised in Detroit, spoke about how his identity as a Nigerian-American student informs his experiences at the University of Michigan. In a school that is overwhelmingly white (a mere 4.4% of the population is Black or African-American), he immediately stands out.

In fourth grade, Ndukwe met a Nigerian student who embraced his culture unapologetically. This student was unafraid to educate other students about why he brought a different kind of lunch to school, or the differences between his how his parents raised him in an African household. Ndukwe was inspired by this classmate, but did not to truly publicly embrace his culture until high school. Torn between wanting to fit in with other black students and wanting to celebrate his culture in public, Ndukwe was both surprised and excited by the strength, unity, and pride of African students at the University. He now serves as president of the African Student Association (ASA), an organization that arranges cultural shows, potlucks, and mixers with other ethnic organizations on campus. Their flagship event is the African Culture Show, a massive celebration of African music and dance that packs the Power Center every year. This year’s show is titled Afrolution: Evolution of African Culture, an inquiry into the future of Africa by African students.

Ndukwe lauds African music as a crucial tether for African students to relate to the culture in their home country. He says that music allows African students to connect with their culture no matter where they are, which is especially important in Ann Arbor, which lacks the music, values, and language of their home countries.

“African music and dance are becoming more and more American,” Tochukwu says. “People there look up to America, they want to be American. African artists are beginning to collaborate with American artists, and I’m like ‘No, don’t lose your culture! It’s so rich!’” Africans are bombarded with American media and feel an increasing pressure to conform music and dance styles to that of American–particularly black American–culture, Ndukwe says.

A very loaded question

We begin discussing gender norms in Nigerian societies (he says many of the Nigerian gender norms are found throughout Africa) and a broad smile spreads across his face. “Oh, boy…you’ve asked me a very loaded question. I don’t even know where to start.”

He says, “African men are expected to be the breadwinners. They’re supposed to be strong, stoic, devoid of vulnerability. They are expected to be the disciplinarian of the family while women are expected to stay home…cook, clean, care for the children.” He explains that the expectation for men to be “macho”, and “hypermasculine” oppresses women, and that the division between genders prohibits women from getting an education and becoming financially independent.

“Mental health hasn’t even begun to be a topic in the general cultural discourse. There’s no such thing as depression, as anxiety for anyone, let alone men. So many men suffer in silence because of it.” As pressures mount for men to be sole breadwinners, disciplinarians, protectors of the family–stoic and strong–many men are subsequently unable to express their emotions with the women they care about. Ndukwe’s background as a Nigerian-born man raised by Nigerian parents tightly bound to their culture informs his relationship with women today. On a personal note, he says that he struggles to express his affection with his significant other. This leads to gaps in communication and rifts in his relationships that are often difficult to repair.

portrait of myself as my father comes at an especially important time. As the consequences of the narrow and stereotypical perception of black men enter the mainstream consciousness, this piece opens the door for discussion.

How does the representation of the black body impact the perception of self as a black woman, an African woman, and an American woman? How has colonialism seeped into the treatment of the black performing body?

Nora Chipaumire asks and investigates these questions in portrait of myself as my father.

See the performance November 17-20, 2016 at the Detroit Boxing Gym in Detroit.

Artist Interview: Actress Aisling O’Sullivan of The Beauty Queen of Leenane

Editor’s Note: University of Michigan student Zoey Bond spent several weeks with Druid Theatre Company as part of the UMS 21st Century Artist Internship program. The Company returns to Ann Arbor with a new production of Martin McDonagh’s dark comedy The Beauty Queen of Leenane on March 9-11, 2017. The interview below is with Aisling O’Sullivan, the Irish actress who plays the beauty queen of Leenane.

Photo: The Beauty Queen of Leenane’s Aisling O’Sullivan (left) and Marie Mullen (right). Photo by Matthew Thompson.

Zoey Bond: You’ve worked on playwright Martin McDonagh’s text before, what draws you to his writing?

Aisling O’Sullivan: It’s his characters, the dilemmas, and the wit, I suppose. It’s more than just the writing. It’s the delight I get from performing in the plays, which is so much fun to do and challenging. They are deep. They’ve got all of the colors.

ZB: As you know, this new production casts Marie Mullen in the role of the scheming mother. She won a Tony Award for the role of the daughter in the 1996 Broadway production. Last week you started wearing Marie’s boots in rehearsal, so you were quite literally stepping into her shoes. What has this part of the process been like?

AO: I found it very difficult. In the past, if I’ve seen a performance, and then I have to do my performance, I think I can do better. I don’t feel I can better than Marie. I saw her originally, and she is just extraordinary and really painfully beautiful. It would have been one of Marie’s defining performances. I’ve known her for a long time, so stepping into her shoes, I’m trying to embrace it and go, “Okay, so I’m privileged to be asked by the same director who thinks there is something I can do that might equal Marie. I’ll give it a shot.” I’m going to do something totally different, or I’ll just do what she did. I’m just trying to embrace the memory of her, and the joy that I got from it. So stepping into her shoes helps me symbolically with all of that. And her shoes are nice.

ZB: So then, the follow-up question is: After seeing the original production, has it been hard for you to create your own version?

AO: Yes. It’s difficult because of the way Martin’s work has to be rehearsed. You don’t get to do the scene over and over from start to finish without stopping. I have no idea who is developing in me until we start running the show. And then I’ll start getting the sense of who this person is. At the moment, it’s very much stop, start, stop, start, which is not conducive for me anyway. I tend to work through moods and energy shifts. I’m not getting the sense of that, which is not a problem. I’m very curious as to who’s going to appear.

ZB: What excites you about audiences seeing this today, 20 years later? What continues to be relevant?

A: Well, I think I love the universality of his darkness in relationships. I love that he puts it out there. It’s impossible not to recognize yourself in these desperate, almost psychopathic relationships.

For me, the play would be about owning your own power, or that if anyone ever encroaches on that space, you have to fight very hard to protect it. You’re in big trouble if anyone masters you — and I’m speaking here about the mother-daughter relationship. You’re in big trouble because you have no power. You’ve lost your own. And dark things can happen from that kind of powerlessness.

ZB: How do you think American audiences will respond to seeing this Irish play?

AO: I don’t know. I performed in front of an audience in America for the first time last year. And it was a very strange and scary experience for me because I’have spent 20 years performing to mostly English and Irish audiences. I can read them. If you get to know a species of audience, you can read them and you know how to play them. But with the American audiences, I had no idea of your taste and your comedy. It was a very interesting experience for me because it was unique. It was a totally different culture. I’m very interested in learning more about that. About how you respond, what’s your funny bone? What things move you?

ZB: In the play, do you have a particular scene, or a moment, or a line that you feel resonates the most with you?

AO: Not yet, but I love the humility, and honesty, and gentleness in a lot of these characters. They drop in these little, gentle sentences, and I think they are gorgeous moments for me to hear, as a performer in it, anyway. That it isn’t just razor-sharp.

ZB: How do you find the love in such a dark play? Do you think it is there?

AO: Definitely. It’s a funny thing that deep love can exist with masses of irritation. I irritate people too, I know that. As you get older, it’s less of a big deal. I’d be horrified to think I was capable of irritating anyone or boring anyone when I was younger, but now I’ve accepted that about myself. I think it’s all over the place.

ZB: Do you have a certain routine that you use to prepare for every role, or does it differ for each production?

AO: I don’t, but I’ll tell you what happened. I have been very instinctive until fairly recently, in that I would come completely open and unprepared to the first day of rehearsal. That was the way I worked and great things could come because I hadn’t made any decisions. Well, I worked on my first Shakespeare with this company last year. I was playing a fairly major part, and I’d never spoken a word of Shakespeare in my life.

I turned up one day, one big Bambi in the forest and the tiger Shakespeare stepped out of the trees. I was pretty much on stage for five hours speaking pure poetry and not understanding it. That was a baptism of fire, and since then, I try to come as prepared as I can be, in terms of learning the lines. I don’t have them off, but I know where they’re going, and then I come into the rehearsal space having done a bit of work. I think that makes me feel much more like an artist.

People who have gone to drama school are horrified listening to me going, “What? No preparation at all?” [Laughs]

ZB: So, there is a fine line between coming prepared and knowing enough, but not knowing too much, so that you can still discover.

AO: Yes. I think if you come in with some ideas, your mind has worked enough on it that you can change course. But if you come in with no ideas, you’re just going to accept the ideas that come to you. I think the crucial bit for me is to love the character. Even if you’re playing a psycho, to find something that you love.

ZB: That’s a good lead into my next question. With which parts of Maureen do you feel you identify?

AO: I identify with the weakness in her, the self-doubt, the way she tries to protect herself in her relationships. I see so much of me, and so much humanity, in her. That’s what is so brilliant about the play. Martin McDonagh was so young when he wrote it, and he just hit the seam of something about human beings that doesn’t often get shown.

Druid Theatre Company returns to Ann Arbor with a new production of Martin McDonagh’s dark comedy The Beauty Queen of Leenane on March 9-11, 2017.

Interview: UMS Choral Union Conductor Scott Hanoian

Photo: Scott Hanoian conducts the UMS Choral Union. Photo by Peter Smith.

Scott Hanoian had just completed his first season conducting the UMS Choral Union in the spring of 2016, when I met with him to chat about the job. As a member of the Programming and Artist Services staff at UMS, I have had the pleasure of hearing the Choral Union perform many times and was especially interested to hear about what Scott had to say about the new repertoire in store!

An organist, accompanist, and conductor, and graduate of the University of Michigan, Scott has held many jobs, including as the current director of music and organist at Christ Church Grosse Pointe, artistic director of the Oakland Choral Society, and faculty member at Wayne State University.

Saba Keramati: What caught your interest about conducting? When did this seem like the right career path for you?

Scott Hanoian: I really didn’t think about being a conductor at all until I was in college. I was an organ performance major at the University of Michigan, but I was also enrolled in beginning conducting class. A good friend of mine was an orchestral conductor, and he said, “You should come to orchestral rehearsals with Ken Kiesler.”

I remember they were doing Shostakovich 5, and I thought, “This is the coolest thing I have ever seen.” About the same time, I was in a conducting class with Jerry Blackstone [who conducted the Choral Union prior to Scott], and it was just clicking. Jerry and I got along really well, and he sent me an email that said something to the effect of, “You should give this a go. You clearly have some sort of knack for conducting.”

I started taking private conducting lessons with Jerry, and I actually enrolled in a graduate conducting seminar for non-conducting majors as an undergrad. Then they let me into the grad program here, and the rest is history. I completely fell in love with it.

SK: How was your first season as UMS Choral Union conductor?

SH: Good! For everybody, I think. One of the interesting parts of my work with the Choral Union is that there are different roles that I play. And this year, we’ve really done everything. I’ve prepared the chorus for someone else, I’ve done a piece they know, and I’ve done a piece that they didn’t know that I’ve conducted. So I’ve been able to experience everything that they do in one season. It’s been a bit of a whirlwind, but it’s a good start.

And I got to stand next to Alan Gilbert on the Michigan football field, so that was pretty cool. Even though I didn’t get to conduct. I wanted to conduct the Michigan marching band, but I’ll have to wait for that.

SK: How does it feel following in Jerry Blackstone’s footsteps after being his student?

SH: They’re big shoes. Big boots, as we say. He was probably my biggest mentor. He’s somebody that I look up to, and it’s an honor to be his successor. I never thought that would be possible. But I owe a lot of that to him because of what he taught me, the advice he’s given me about teaching, and the compassion he’s shown me. He’s the most gracious predecessor I could ever imagine and I love that about him. I am very lucky to have somebody like that just down the road.

UMS Choral Union prepares for Handel’s Messiah performances during 2015-16 season.

SK: What makes the UMS Choral Union special?

SH: They’re phenomenal singers. A group of intelligent, passionate, and really compassionate people that come together to make a commitment to the composer and piece that they perform. They are coming from all different walks of life: they’re working full time and singing, they’re students, they’re retired, they’re travelling all the time… but they come together Monday nights to sing phenomenal repertoire. I love working with people that are just so energetic about what they do.

SK: What should we look forward to in the 2016-17 season?

SH: Messiah, of course. We love Messiah [December 3 and 4, 2016]. They’ll also do some new repertoire. The Beethoven Missa Solemnis with the Ann Arbor Symphony at Hill Auditorium as well as with the Toledo Symphony [March 11 and April 28, 2017, respectively]. The singers will be working very hard, because not only will we be doing that, we’ll be preparing the Beethoven 9 for both the Budapest Festival Orchestra [February 10, 2017] and the DSO. We have a lot of a Beethoven on the horizon. That music will really showcase our singers.

SB: Anything else you want audiences to know?

SH: One of the things the Choral Union prides itself on is that we have no paid singers, it’s an all volunteer chorus, and it’s one of those groups that is entirely self-managed. We have vocal coaches and section leaders all within the group, and it’s a really great synergy of volunteers. It’s a chorus that runs itself. Obviously we work within the UMS auspices, and we have UMS staff liaisons, but there’s a certain corps of people that just sing because they love it. And I think that’s very important. They’re a very tight knit group, and they’re very loyal. I love that about them.

For more information on the Choral Union, including a list of their upcoming shows and audition opportunities, visit http://ums.org/about/choralunion/

Artist in Residence Update: Grensis

Editor’s note: Ben Willis is a musician and composer and one of our 2015-2016 artists in residence. As part of this program, artists in residence attend UMS performances to inspire new thinking and creative work within their own art forms.

Here, Ben is in conversation with Lester Crespum, an intuitive design specialist, explorer, and specious theorist.

Ben Willis: While I know I’m at risk of injecting my own biases and suppositions into this discussion, I’d like to talk to you about how you feel about being a multidisciplinarian, the expectations and challenges thereof, and also about this looming thing called the future, which all of us understand exists, but few of us really acknowledge.

Lester Crepsum: I’d like to begin with your second point.

BW: The future.

LC: Yes.

BW: Go ahead.

LC: (silence)

BW: Are you still there?

LC: Yes, I apologize, I was merely engaging with inevitability. I find that most claims are best reached when mediated by silence. In the case of the future, whose even existence is debatable – yet, inevitable, the question is more a case of the why than the what.

BW: Isn’t that always the case?

LC: I actually find the opposite to be true. I find myself asking “What?” and “What is that?” about pretty much everything. I also have an extremely poor short-term and long-term memory, requiring me to rely heavily on bionic augmentation.

BW: Technology?

LC: I’m currently in the process of developing, along with a team of technologists, a series of sensory augmentation ports that I could permanently inject into my spinal column.

BW: This will improve your memory?

LC: Better, it will be incredibly painful, which will serve as a constant reminder that I am alive. So often, when just sitting, or even in situations when I am being engaged, like now, I slip into an automatic mode of existence – of relying upon my own brain. While I know that I exist entirely within my own brain, and yes, since solipsisms (once radical, now boring!) are a thing, YOU, and EVERYTHING ELSE could very well (and probably do) exist entirely within my brain, it helps to be reminded that I’ve chosen to believe otherwise. These sensory augmentation ports in my spinal column would serve as nodes of interaction with the outside world, hyperventilated and fabricated pituita serving as divine access to the noumenal. (And by noumenal, I mean anything that isn’t me, of course, or at least everything that isn’t me and also isn’t my brain, which could very well be nothing. Thankfully, there’s so much more nothing than there is something! That’s where those questions “What?” and “What is that?” come in handy. Most of the time, the answer is “I don’t know!” or, even more aggravating, “What?”)

BW: Let’s talk about that parenthetical. You find the answer is often the question, “What?”

LC: What?

BW: I see.

LC: The future is mostly a realm of expectation. It will be or it won’t. Where do you think we will be in five years?

BW: What?

LC: Exactly! When I was embedded with the Zintook tribe in southern Smibwenbia, one of the most useful things I learned was a form of greeting. Between men, this was enacted by taking each others’ hands, making direct eye contact, and very slowly bringing your tongues to touch. The rest of the men would form a circle around you making a falsetto “Lululu” sound, in imitation mockery. Between a man and a woman, the greeters would lightly take each others’ hands, and then the woman would smack the man in the face, backhand, and then laugh. Between two women, they would just make eye contact, wink at each other, and then smile impishly. If there were other genders present, or gender fluid individuals, they would just pick one of these actions and perform it. Which was kind of more fun for the other person, if they didn’t know what was going to happen, like if a man starts going for the tongue thing, and then gets backhanded in the face! I’ve never laughed so hard.

BW: I’ve never heard of this tribe.

LC: Yes, sadly, they are largely decimated by now. And those left mostly act as weapon runners.

BW: It’s a cruel world.

LC: Business is booming for cruel people.

Interested in more? Follow the adventures and process of other UMS Artists in Residence.

Interview: Theater maker Young Jean Lee

Moments in Untitled Feminist show (left) and Straight White Men (right). Photos by Julieta Cervantes and Brian Mediana.

“Young Jean Lee is, hands down, the most adventurous downtown playwright of her generation.” (New York Times) This January, UMS showcases Young Jean Lee’s two most recent theater works on gender and identity. The plays are performed across the street from each other in the Power Center and Lydia Mendelssohn Theatre.

UMS Lobby regular contributor Leslie Stainton interviewed Young Jean Lee ahead of the visit.

Leslie Stainton: How do you define “theater”?

Young Jean Lee: I don’t have a definition for it. If someone calls it “theater,” then to me it’s theater.

To my knowledge, this will be the first time anyone’s deliberately paired Untitled Feminist Show with Straight White Men. What do you hope happens from that juxtaposition? What are you most curious about?

The shows are so different and appeal to such different audiences, but for me they’re both coming from a similar place. My hope is that seeing them back to back will encourage audiences to look for their similarities.

How do you go about choosing a language—verbal, nonverbal—for a specific work about a particular topic?

I’m always trying to find the best match between form and content. For the first workshop of Untitled Feminist Show in 2010 I wrote a script and after the showing, our audience did nothing but make academic arguments about feminism. I wanted to hit people on a more emotional, visceral level, so as we did more workshops, I kept cutting out more and more of the text until there was nothing left but movement, and the audience was forced to react emotionally. I tried hard to write words that could compete with the movement and dance, but I couldn’t. We found that movement communicated what we wanted much more strongly than words did

For Straight White Men, I saw the traditional three-act structure as the “straight white male” of theatrical forms, or the form that has historically been used to present straight white male narratives as universal. And I thought it would be interesting to explore the boundaries of that form at the same time as its content.

What role do you see for live performance in our technological age? In what ways, if any, must live performance evolve and/or adapt in a world of rapid technological change?

Theater has been around forever—it’s survived the advent of radio and television and film. It’s become part of our educational system. I don’t really see it going anywhere.

What issues are you yearning to tackle in your work (or not, given your penchant for writing about “the last thing” you’d want to write about!)?

The Native American genocide has been on my mind a lot lately.

What are you working on now?

I’m trying to figure out how to make my first feature film!

When did you first fall for live performance?

There was a summer stock theater in the town where I grew up, and my parents took me to see A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum when I was very young, and I was hooked.

Many of your pieces deal with identity. In what ways is theater especially well suited for addressing questions of identity?

I don’t know that it is. Identity is hard to address in any art form, I think.

What key trends do you see in American theater today?

I think that contemporary American theater is very aesthetically conservative, and that it charges way too much for tickets. It isn’t adventurous or challenging enough — I’m thinking of mainstream commercial theater where everything has a linear plot line and there’s very little formal experimentation. I think the New York experimental theater/performance scene is still exciting. The stronger artists tend to have longer developmental processes. The performers have a lot of charisma and intelligence. There’s a lot of collaboration. On the other hand, I think a danger with experimental theater is when it gets locked into its own kind of tradition and you just see a bunch of experimental-theater cliches being played out.

See Young Jean Lee’s Straight White Men and Untitled Feminist Show in Ann Arbor January 21-23, 2016.

Our Very Own Audra McDonald Round Up

Audra McDonald. Photo by Andrew Eccles.

We can’t wait for the return of six-time Tony Award winner Audra McDonald. She’ll perform at Hill Auditorium on September 17, 2015.

UMS has had the honor of presenting Audra McDonald a few times over the course of recent year, and the singer has been very generous with her time with students, staff, and more.

Here’s a round up of our favorite Audra McDonald moments in the past few years.

1. The one where she raves about Ann Arbor audiences:

2. The one where she sings a birthday song for Hill Auditorium:

3. The one where she answers questions from University of Michigan students:

4. And of course, the one where we got to ask a few questions.

What are your favorite Audra McDonald moments?

A Community of Singers, Right Here in Ann Arbor

Photo: UMS Choral Union on stage for Handel’s Messiah at Hill Auditorium. Photo by Mark Gjukich Photography.

Karen Isble is Assistant Vice President of Development at the University of Michigan, and she’s also been a member of the UMS Choral Union, Ann Arbor’s 137 year-old, Grammy Award-winning community choir, for nearly eight years.

We chatted with her about her most memorable experiences, including a performance in blizzard conditions, the community, and outgoing music director Jerry Blackstone.

Karen Isble

UMS: What do you love about singing?

Karen Isble: I’ve been a singer all my life. I have two music degrees, one of them in voice performance from the University of Michigan. Earlier in my life, I had visions of becoming a professional performer. When that didn’t come to fruition, I wanted to make sure that I had an opportunity to use that part of myself. Singing became my avocation. I joined the UMS Choral Union in 2007 when I began to work for the University.

UMS: 2007, you’re coming up on eight years with the Choral Union, wow! What are some of the highlights of your experiences with the Choral Union?

KI: One of the highlights, and there have been many, was singing the Saint Matthew Passion several years ago in what was the last blizzard of that spring. I work here on campus, so I had an advantage over a number of folks who were coming in, some people come from as far as Ohio, and certainly from the rest of southeastern Michigan or East Lansing. Members of the Detroit Symphony were coming in from Detroit. We had a children’s choir coming in from Michigan State University.

This snow storm was horrible, and I think it was going to be a three hour concert. As the choir arrived, UMS president Ken Fischer came out on stage and said, “Let’s everybody get the choir on stage. We’re waiting for the orchestra to get here, we’re waiting for the kids to get here, go out and wave your hands so that the audience knows something’s happening.” So, I think, the choir, or those of us who had made it there, ended up going out and sitting on the risers for about an hour while we sort of waited for everyone else to arrive.

Amazingly, the house was packed. I thought there’d be tons of empty seats, but the audience was full to the rafters, all the way up to the second balcony. As each group of musicians showed up, these cheers would go up from the audience. And once the children’s choir arrived, there was an ovation. So then, about an hour late, we dove into this wonderful, wonderful, incredible piece of music, which I hadn’t sung in about twenty years up to that point. So I was really thrilled to have the opportunity to do it again. I had a small solo that Jerry Blackstone had granted me. It was a very transformative performance. It was just this badge of honor, we had made it through this blizzard and we had a wonderful evening.

UMS: A truly “Michigan” story!

KI: There were tales of people abandoning their cars. I remember that a member of the choir said, “I abandoned my car, I couldn’t drive any further. I just walked the rest of the way.” That sort of thing.

UMS: Has there been anything surprising in your experience with the Choral Union? Something that has challenged you or something that’s been a particularly good learning experience for you as a singer?

KI: Before the Choral Union, I’d mostly done solo singing, chamber music, small choir singing, and I wasn’t really sure I would enjoy singing with a group this size. Every year we’d start out with close to 200 folks of every skill level. What has surprised me over and over again is how beautiful and agile a choir of 150 to 200 people can be, and what incredible music we can make. It doesn’t happen all of the time, sometimes we’re just big and loud! But when we have an opportunity to be something a little different, I’m always pleasantly surprised at how well the group comes through.

UMS: It seems that there’s a real sense of community outside of the singing, too, within the group. Would you say that that’s true?

KI: I think that’s true. I think there are a lot of folks, certainly, who have been with the Choral Union for decades, and they have sort of formed that foundation. But I think one of the things that the group does well is have a huge spectrum of participants. We have students who join each year and are part of the equation, and that’s nice, and they’re a little more fluid. Many of the members are also one-time students who have come back a decade later, working in the Ann Arbor area now and looking for another creative outlet.

But definitely a sense of community. I think it grows on you the longer you are there. It takes a bit of time to find your place in a group that big. I certainly feel very at home with the Choral Union though I don’t know everybody, I don’t know that I ever could. You get to know the faces, and when you see them in unexpected places around town you kind of give that high-five or, “Hey, how’re you doing?”

UMS: What would you say to someone who is considering joining the Choral Union?

KI: For me, singing in the Choral Union is my respite from the day-to-day grind. It’s a wonderful escape. It’s hard, actually, sometimes to get myself pumped up for it on a Monday night after a full day’s work, but as soon as we start to sing, it’s almost immediate, and I always leave revitalized. And so I would say if people are thinking about it, weighing adding it to their schedule, that the Choral Union can re-energize you is a really important part of that.

UMS: The Summer Sings on July 6 is the final Choral Union moment for outgoing music director Jerry Blackstone. Would you like to say anything about your experiences with Jerry?

KI: I had the opportunity, as a University of Michigan grad student, to sing with Jerry. As I mentioned, he was the catalyst for my joining the Choral Union. Jerry has fostered the Choral Union community. His ability to be so musical and so warm and so inviting to everyone at every musical level really made the difference during his term as the music director.

Do you sing? New singer auditions for the UMS Choral Union will be held in August and September 2015.

Artist Interview: Petra Haden, violinist and vocalist

Photo: Petra Haden. Photo by Steven Perilloux.

Violinist and vocalist Petra Haden has been a member of groups like The Decemberists and has contributed to recordings by Beck, Foo Fighters, and Weezer, among others. With her sisters, Petra is a member of the group the Haden Triplets and will also be familiar to UMS audiences as the daughter of the legendary jazz bassist Charlie Haden.

She performs as part of guitarist Bill Frisell’s When You Wish Upon a Star group on March 13, 2014 in Ann Arbor. The two have also created recordings together.

Greg Baise is the curator of public programs at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit. This summer, Greg spoke with Petra about working with Bill Frisell, growing up in a musical family, and her interest in the nooks and crannies of film scores.

Greg Baise: This particular UMS appearance actually encompasses two evenings and is called the Bill Frisell Americana Celebration. The first evening features Bill Frisell on guitar solo. And the second evening features you as part of When You Wish Upon a Star, a relatively new band. Can you tell me more about the band and the material you’ll be working on for the concert?

Petra Haden: We’ll play from our record, the first record [Bill and I] did together. This record came to be after I played a show in Seattle with a friend of mine, and Bill came to see that show. He was interested in what I was doing, and he called me soon after to ask if we could do a record together. I was really excited to work with him because I’m such a huge fan! We decided to record a collection of our favorite songs, a variety of music from Coldplay to Stevie Wonder to Tom Waits. “When You Wish Upon a Star” was one of the songs we worked on, and our concerts together so far have been a mixture of these songs as well as Gershwin songs.

GB: In another interview you said that Bill gets your brain. What do you mean by that?

PH: It’s something that I can’t exactly put into words. It’s so hard to describe. When we play, it’s like this language that we speak together. It’s almost like he can predict where I’m going to go next. I remember hearing him when I was younger and thinking how beautiful it was, and to finally be recording with him is a dream come true.

When I was recording with Bill for my Petra Goes to the Movies album, one of the engineers told us that we seemed like brother and sister when we worked together. So, it’s also apparent to others that we’re a good match musically.

GB: I’d love to hear about the arrangement process. Do you and Bill work together to come up with arrangements for these songs?

PH: When we started working on our first record, Bill played and I sang the melody. When we were done with the basic tracks, I added violin. I just came up with stuff on the spot. I played what I heard in my head. I came up with the string ideas for songs that I’d heard, like the songs by Stevie Wonder, and also for songs like Elliott Smith’s “Satellite,” which I’d never heard before, but Bill had played for me. That’s another way he gets my brain. He told me that I had to hear this Elliott Smith song, and that became my new favorite song. He gets my taste is in music.

GB: Listening to you as you create harmonies on the record is pretty astounding. Does it come from something that you studied, or maybe from your upbringing in a musical family?

PH: I started singing with my sisters when we were really young, probably six or seven. We used to visit my dad’s family in Springfield, Missouri. They had a radio show called “The Haden Family,” and we would sit in the living room and have fun, eat, and sing together. That’s one of the first experiences I had with singing harmonies. I remember knowing at a very young age that I loved singing harmonies, and as I grew up with my sisters, we sang just for fun.

I wasn’t really active in music in high school. But later, after I graduated, I joined a band called That Dog with my sister Rachel and another high school friend. I was involved with that band for five years. I ended up going to music school at Cal Arts (California Institute for the Arts), but just for a year, so I never really had formal music training. That’s why I tend to do everything from my head, which can be hard.

GB: Has your record with your sisters, The Haden Triplets, been in the making since your childhood?

PH: Ten years ago or so we worked with a friend who wrote a few songs for us, but we weren’t recording an album at that time—it was just for fun. Any show we played, we sang these songs, and we added [the American folk group] Carter Family songs that we’d known since we were kids. But we were all busy and didn’t pursue an album, though people often asked us when we might record.

Later, we were asked to perform at a tribute show for soul and jazz poet Gil Scott-Heron, and when percussionist Joachim Cooder found out that we were a part of it, he wanted to play drums with us. He mentioned that his dad [the guitarist Ry Cooder] was interested too, so Ry played guitar with us for that show. He’s the one who called me after to say that he was interested in producing a Haden Triplets record. I was very excited because I’m a big Ry Cooder fan. We recorded it at my sister Tanya’s house before she moved in. It’s an old, big house with tall ceilings, and it was empty, so it was a great place to record.

GB: Your most recent record is Petra Goes to the Movies. I’d like to hear about your relationship to film scores in particular.

PH: I’ve always thought about doing an A Capella “Movies” album. Since I was a kid I was obsessed with all the Superman movies. I had the vinyl for the soundtracks, and I listened to them a lot and sang the string parts in my head. That was my favorite thing about going to the movies, listening to the music. Music is what tells me the story whenever I watch a movie.

GB: In the album, you’re looking at the nooks and crannies of a soundtrack that people don’t normally look at.

PH: That’s interesting that you bring that up. Often in movies, the music that I wish was on the soundtrack doesn’t ends up on it. Like in Big Night for instance, there’s a scene that just touched me, during which the owner of the restaurant with which the brothers compete plays piano. I don’t think that’s even on the soundtrack. My friend (who engineered the album) got the video and recorded it for me so that I could hear it.

Bill plays on that album too, so it’s not entirely A Capella. He thought of the theme from Tootsie, one of my favorite movies, and that’s another example of the way that he just gets my brain.

GB: Are you planning on recording another album with Bill and the When You Wish Upon a Star group that will play in Ann Arbor, or is that to be determined?

PH: That’s to be determined. I want to record with Bill for sure, but for my next record, I’m focusing on original songs. I work really well with collaborators, so I want to find the perfect writing partner.

GB: Earlier, we talked about the way you’ve admired Bill’s work for a long time. You said that to work with him is almost like a dream project. Do you have a list of other dream projects, whether that’s material or collaboration?

PH: Lately, I’ve been listening to an album by Mark Isham called Vapor Drawings. I don’t know how to get in touch with him, but he’s someone I would want to work with. I would definitely love to work with [the composer] Steve Reich, to be one of his singers. His music is another way I learned to harmonize. I love that pulsating singing so much. My other favorite guitarist is Pat Metheny. I did have the chance to work with him when I worked on my dad’s record Rambling Boy. On that record, I sing on a song that Pat plays on, which was a dream come true.

GB: Thanks for taking the time to talk! I was really excited when I saw that you would be playing in with Bill Frisell.

Artist Interview: Jennifer Koh, violinist

Insightful and passionate violinist Jennifer Koh talks with UMS Lobby contributor and composer Garrett Schumann about creative programming choices, contemporary works, and the power of music.

The virtuoso violinist returns to Ann Arbor (following her 2012 appearance in the Philip Glass and Robert Wilson opera Einstein on the Beach) with the third and final part of her Bach and Beyond series on Friday, February 6, 2015.

Garrett Schumann: Throughout your career you’ve maintained a consistent interest in programming contemporary and often newly-commissioned works alongside standard pieces in the violin repertory. Where did this passion for combining tried-and-true pieces with new pieces come from in your development as a violinist?

Jennifer Koh: I think it was always just curiosity. When you first make your foray into discovering classical music, it’s really new to you. Now, to me, it doesn’t really matter what time period the music comes from, whether it is “new” or “old.” The one thing that has been such a great pleasure about working with contemporary music is that I can actually get to meet and work with living composers, and that has been a really wonderful, beautiful part of doing the work.

GS: Do you think that putting older pieces next to contemporary work brings new things out of them?

JK: Everything is in context. We live in a certain age, and every day that passes takes us one day further away from the society of Bach, for example. I actually remember hearing a program by Peter Serkin. This program was a little unusual for him; he was doing all the Bach concerti, and what was fascinating was that everything sounded so modern. I realized that art is about re-discovering.

When I first created the Bach and Beyond program, I bookended the program with Bach because I wanted to create a journey through history and into our contemporary landscape and then return to Bach. You create this circular journey, and you realize that the experience of listening to the things in the middle changes how you hear Bach. And, in a way, it also changes how you frame each of the composers.

I feel that contemporary music links us to the past because it does have this history. Most composers work within the richness of that tradition, but they also add their personal viewpoint to it. The great thing about art, and the great pleasure for me personally as a musician, is that it has the ability to change the world. It creates a situation where people can have a space to be very present, but also go to places that they normally don’t want to go to and access those emotions that they don’t necessarily experience every day.

GS: Speaking of this sort of cyclical nature of Bach and Beyond, what’s really interesting about your performance this season is that when you did your first UMS performance in 2010, you were at the beginning of the Bach and Beyond series. Now that it’s coming to a close, how does that feel?

JK: It’s been an interesting process. I actually remember the very beginning, when it was still very difficult to convince people to do this solo violin program. And I remember when I first came up with the idea, a lot of people said, “Nobody’s going to want to book that.” Nobody does solo violin programs. But now, Bach and Beyond has become much more accepted, so one of the beautiful things for me has been that people have begun to see violin as an instrument that has enough timbre to hold an entire program.

I was also at UMS with Einstein on the Beach, and that experience opened my world in a wonderful way. Those performances were the first preview performances of Einstein, and the first extensive rehearsal process was there. It feels like UMS has been a starting point, and so it’s nice for me to return.

GS: What was the experience of working with director Robert Wilson during Einstein on the Beach like for you?

JK: It was really organic in the sense that it’s always been interesting for me to work with artists that I really admire and respect. When I first met [Robert Wilson], I was intimidated. But then, when I saw how he worked, I felt an immediate connection. I respected his working style because he is a perfectionist, and that’s something that I do myself.

When I got the call for Einstein, I knew immediately that I wanted to be a part of it. But I was actually terrified because I don’t have any acting background. But things that terrify me, I find the most interesting. For example, doing Bach and Beyond when I first thought of it was terrifying as well.

What I hope in the end for any piece, whether it’s Einstein or Bach and Beyond, is that people who actually hear the piece trust you. And that they’ll go along on the journey.

GS: Now that Bach and Beyond is wrapping up, what do you have set up for the future?

JK: My next purely performance-based project is called Bridge to Beethoven. That is really an exploration of all ten Beethoven sonatas, but will also have four new works in conversation with it.

When I first came up with the idea, I had just seen a production of Julius Ceasar by the Royal Shakespeare Company. They had made Julius Ceasar a despotic military junta leader in Africa. Again, that inspired me to think about how changing the setting can really alter our assumptions.

So when I was exploring the Beethoven sonatas, I wanted to approach the assumptions that we have in our current psychology. For a lot of people, Beethoven is the “definition” of classical music. If you say “Beethoven,” people tend to have a very specific perception of the music. The question for me, became, “How has classical music evolved?” If you look at his music, he was quite a revolutionary, but now oftentimes it’s performed such that it doesn’t sound new, it doesn’t sound modern. For me, what was important was to bring out these parts of the music that are not just “elevator music.” To really hear those revolutionary aspects in his compositional process.

What’s also interesting to me and helped to inspire this project is that I come from a non-musical background, but at one point, I discovered music is something that I love. Many American composers also come from non-musical families, so what is it about music that draws us to that platform? I wanted to create that kind of dialogue in a compositional way.

My ethnic roots are also in a country halfway across the world in Asia. How is it that I came across classical music? How is it that this art form has changed my life to the degree that I can’t imagine my life without music? Questions like this are reflected in the project as well.

Anyhow, we’re actually starting it late next season and we start it in California, then we take it to Virginia, and then it will go to New York.

GS: Well, I have to say that as a young idealistic grad student, I really appreciate the consideration you put into the program and the fact that you want to address issues that are larger than the music or parts of the music, these are things that are sometimes missed in the traditional setting.

JK: I agree. There is this idea of reaching outside of what you already know, and it’s becoming less and less common. I think that the arts are great because they are an open experience that’s about empathy, about having an experience that you don’t have on a normal basis.

Interested in learning more? Check out other interviews by Garrett Schumann.

Artist Interview: Flutist Tim Munro, eighth blackbird

Eighth blackbird. Photo By Luke Ratray.

The Chicago-based ensemble eighth blackbird combines the finesse of a string quartet, the energy of a rock band, and the audacity of a storefront theater company in a dazzling performance coming to Ann Arbor’s Rackham Auditorium Saturday, January 17, 2015.

Composer and UMS Lobby contributor Garrett Schumann chatted with eighth blackbird flutist Tim Munro about the group’s unique instrumentation, theatrical flair, and magical moments onstage.

Garrett Schumann: What is eighth blackbird?

Tim Munro: Well, eighth blackbird is a chamber music ensemble specializing in music by living composers. One week we might play music that’s influenced by indie rock, the next music influenced by Balinese Gamelan, the next by an abstract piece of modern visual art.

We often memorize the music that we play, which allows us to take away stands and to have a greater intensity of communication on stage and with the audience. Sometimes that means we actually move around the stage to make manifest some of the relationships that are already inherent in the music. So a lot of the time we are trying to make this new composed music more immediately vibrant and engaging for audiences.

GS: Terrific. When you created the group in 1996 there had been ensembles with the same instrumentation as eighth blackbird for a few decades. How consciously did you guys see yourselves as emerging from that kind of ensemble tradition?

TM: To speak about the instrumentation first, eighth blackbird was sort of a put-together group. At the Oberlin conservatory, this conductor, Jim Weiss, put the group together to play more challenging repertoire, stuff that isn’t normally covered in the run of conservatory conductor. And this instrumentation seemed like the perfect kaleidoscope in everything. You have strings, you have winds, you have piano, you have percussion. You’re able to sound like you’re a string quartet, you’re able to sound like you’re a piano trio, you’re able to sound like a percussion ensemble, you’re able to sound like a full orchestra and there is just every combination possible in this instrumentation. This, I think, is why in the 20th century, it really exploded.

I think the biggest influence on eighth blackbird is an ensemble with a different instrumentation, which is the Kronos Quartet. It plays a hugely diverse range of material. Everything from the wildest, most experimental modernism to the kind of obvious, fun-loving minimalist to collaborations with popular artists and world music– and doing it in a way that made it visually engaging to audiences, but was casual enough that people could feel relaxed. So I think that was the biggest influence on eighth blackbird in its earliest stages.

GS: How do you come with this diversity of programming? What do you think it is about eighth blackbird that does that diversity so well?

TM: I think that’s something that we try very hard to represent in our programs not just because we want to check all the boxes, but because we want people to never feel bored, but to always have people engaged in a concert. The diversity of the programming just reflects the diversity of different proclivities within the ensemble. Each performer in eighth blackbird is part of the artistic direction of the collective. We are all music directors of eighth blackbird and we are all coming from very different places. We all have different music that we love and I think our programs are reflective of the enthusiasm of the group all together.

What unites all of the music that we play is something in it that is unique: a color that we haven’t heard, a particular approach to constructing a piece that we haven’t done before, a spark that inspires the piece that we haven’t encountered before… something that we can then play with theatrically. So each piece on the program in some way captures something that is unique even if they are in totally different worlds. Everything on the program gives us a little something atypical or strange.

GS: Composer and Northwestern professor Lee Hyla passed away suddenly in June 2014. What was your group’s relationship with Lee Hyla and his piece “Wave”?

TM: Well, it was such a shock for everyone in the ensemble and for the whole music community in Chicago because he was such a huge presence. He’s an original. His music has a rawness and an unvarnished-ness that feels so appropriate and typical of someone of that sort of American maverick tradition. Every member of the group has a particular fondness for one of Lee’s pieces and we all loved his music. We don’t know him well personally, I don’t think anyone in the group knew him terribly well, but we are all such huge fans and were all so excited to be able to commission the piece.

I can tell you that already in rehearsing this we’ve discussed how the piece is put together. It’s a lot of fragments, it’s a piece that’s shards of things. Beautiful, pummeling, fractal, little elements that are all in shards, sort of constructed. And when we come to the moment of rehearsal where we don’t quite know our way forward, that’s often when we will talk directly with the composer. And so whenever that happens, we have that voice in the room, but we won’t be able to do that. So I’m not sure how it will affect our performance. It’s too soon for us to say.