From Margins to Mainstream: A Brief Tap Dance History

Originally published October 5, 2016. Updated June 21, 2019.

Photo: Dorrance Dance in performance. The company returns to Ann Arbor on February 21-22, 2020. Photo by Nicholas Van Young.

Brief History

Tap dance originated in the United States in the early 19th century at the crossroads of African and Irish American dance forms. When slave owners took away traditional African percussion instruments, slaves turned to percussive dancing to express themselves and retain their cultural identities. These styles of dance connected with clog dancing from the British Isles, creating a unique form of movement and rhythm.

Early tap shoes had wooden soles, sometimes with pennies attached to the heel and toe. Tap gained popularity after the Civil War as a part of traveling minstrel shows, where white and black performers wore blackface and belittled black people by portraying them as lazy, dumb, and comical.

Evolution

20th Century Tap Tap was an important feature of popular Vaudeville variety shows of the early 20th century and a major part of the rich creative output of the Harlem Renaissance.

Tap dancers began collaborating with jazz musicians, incorporating improvisation and complex syncopated rhythms into their movement. The modern tap shoe, featuring metal plates (called “taps”) on the heel and toe, also came into widespread use at this time. Although Vaudeville and Broadway brought performance opportunities to African-American dancers, racism was still pervasive: white and black dancers typically performed separately and for segregated audiences.

Tap’s popularity declined in the second half of the century, but was reinvigorated in the 1980s through Broadway shows like 42nd Street and The Tap Dance Kid.

Tap in Hollywood

From the 1930s to the 1950s, tap dance sequences became a staple of movies and television. Tap stars included Shirley Temple, who made her film tap dance debut at age 6, and Gene Kelly, who introduced a balletic style of tap. Fred Astaire, famous for combining tap with ballroom dance, insisted that his dance scenes be captured with a single take and wide camera angle. This style of cinematography became the norm for tap dancing in movies and television for decades.

The Greats

Master Juba (ca. 1825 – ca. 1852) was one of the only early black tap dancers to tour with a white minstrel group and one of the first to perform for white audiences. Master Juba offered a fast and technically brilliant dance style blending European and African dance forms.

Dancer Jeni LeGon with dancer (and musician) Chester Whitmore in 2009. Joe Mabel/Century Ballroom

Bill “Bojangles” Robinson (1878—1949) began dancing in minstrel shows and was one of the first African-American dancers to perform without blackface. He adapted to the changing tastes of the era, moving on to vaudeville, Broadway, Hollywood Radio programs, and television. Robinson’s most popular routine involved dancing up and down a staircase with complex tap rhythms on each step.

Clayton “Peg Leg” Bates (1907-98) continued to dance with after losing a leg in a cotton gin accident as a child. He danced in vaudeville, on film, and was a frequent guest on the Ed Sullivan Show. Bates also frequently performed for others with physical disabilities.

Jeni Le Gon (1916-2012) was one of the first black women to become a tap soloist in the first half of the 20th century. She wore pants rather than skirts when she performed and, as a result, she developed an athletic, acrobatic style, employing mule kicks and flying splits, more in the manner of the male dancers of the time.

The Nicholas Brothers Fayard (1914-2006) and Harold (1921-2000) Nicholas had a film and television tap career spanning more than 70 years. Impressed by their choreography, George Balanchine invited them to appear in his Broadway production of Babes in Arms. Their unique style of suppleness, strength, and fearlessness led many to believe that they were trained ballet dancers.

Gregory Hines (1946-2003) introduced a higher complexity of the improvisation of steps, sounds, rhythms. Hines’s dances were rhythmically involved and often strayed from traditional rhythmic meters. Savion

Glover (b. 1973) is best known for starring in the Broadway hit The Tap Dance Kid. Glover mixes classic moves like those of his teacher Gregory Hines with his own contemporary style. He has won several Tony awards for his Broadway choreography.

The Blues Project – Dorrance Dance Company with Toshi Reagan and BIGLovely

Dorrance Dance returns to Ann Arbor on February 21-22, 2020. Content created in collaboration by Jordan Miller and Terri Park.

Camille A. Brown’s Inspirational Moves and Message

Camille A. Brown & Dancers mesmerized audiences and schoolchildren across Southeast Michigan during their January residency.

From workshops in K-12 schools to community dance events, a sold-out School Day Performance, and the UMS debut of their powerful work, ink, here are seven of our favorite moments:

1. Teaching Artist Workshops

UMS Teaching Artists worked with Scarlett Middle School students and other local schools to learn about Camille Brown’s unique choreography and movement, in preparation for their upcoming School Day Performance. To bring the lesson full circle, Teaching Artists returned to each school to lead post-performance workshops.

2. Learning History through Dance

Company member Catherine Foster led a Community Movement Workshop in Detroit’s Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History, taking participants on a journey of dance history. From a call-and-response warm-up to the “Lindy Hop”, swipe through our Instagram post to watch the class unfold!

View this post on Instagram

3. Master Class at U-M

While on campus, company member Juel D. Lane led a creative and thought-provoking master class with University of Michigan dance students.

4. A Cool School Day Performance

More than 1,200 K-12 students from 13 area schools (including every Scarlett Middle School student) arrived at the Power Center for a sold-out School Day Performance. The Company’s mix of cool moves, hip-hop, rhythm, and visual storytelling drew countless oohs and aahs from the young crowd!

5. A Special Q & A

After the performance, students from Scarlett Middle School met with the company. Camille shared how she found the power to express her voice through dance. She encouraged students to be resilient and stay close to their community of support, especially in the face of criticism, remarking, “If you don’t believe in who you are and what you’re doing, who will?”

6. You Can Dance!

Camille A. Brown & Dancers company members Timothy L. Edwards and Maleek Washington invited local dancers of all ages and levels to explore movement with them at the Ann Arbor Y.

7. A Poignant Closing

“Energizing, thought-provoking, and simply beautiful” is how one audience member shared his appreciation for ink, the final installation of the company’s trilogy of stories of Black identity. Explosive choreography and the rhythmic interplay between the musicians and dancers left Saturday night’s audience enthralled and wanting more.

A lively Q & A after the performance shed light on the symbolism and meaning behind the theatrical choreography — all intended to expand the narrative of hopes, dreams, relationships, and community beyond entrenched stereotypes.

—

Our sincerest appreciation to Camille A. Brown & Dancers for a beautiful week of movement and creative inspiration. Follow @CamilleABrown on Instagram to keep up with the company’s work on and off the stage on Instagram.

Faculty Spotlight: “Written in Water” in U-M Classrooms

In October 2017, UMS presented Ragamala Dance Company’s Written in Water. University of Michigan students had the opportunity to experience the performance, many attending with a University of Michigan class that incorporated Written in Water into the curriculum.

Veronica Dittman Stanich interviewed faculty who shared their experience with the work and impact on students.

Photo: Ragamala Dance Company performance in 2016. Courtesy of artist.

On October 20, 2017 UMS presented Ragamala Dance Company’s Written in Water at the Power Center. Ragamala’s work is grounded in the classical South Indian dance form Bharatanatyam, but its artistic directors, Ranee and Aparna Ramaswamy, continue to push its traditional boundaries, working in contemporary choreographic contexts and collaborating with a range of musicians and visual designers. In Written in Water, they bring together themes of spiritual ascension from an ancient Sufi text, a Hindu myth, and Paramapadam—an Indian antecedent of the board game Snakes and Ladders. The dance unfolds against a backdrop of projected images by artist Keshav and is accompanied by Amir ElSaffar’s heady blend of Middle Eastern music and jazz, performed live by ElSaffar and a small ensemble of musicians. Faculty across the University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts integrated the performance into their syllabi, bringing over 250 students to the performance. Here, some of these faculty explain how Written in Water functioned in their courses and how it impacted their students.

Photo: Ragamala Dance Company. Courtesy of the artist.

Yopie Prins brought all 125 students from Great Performances (Comparative Literature 141) to Written in Water. For this course—a First Year Writing Requirement similar to a “Great Books” course—students see performances from across genres, including music, dance, theatre, and opera. Prins explains, “I like to hold open a space for canonical works from non-western traditions. Ragamala brings together classical Indian dance and a more contemporary American aesthetic.” To prepare for this form that was unfamiliar to many students, they read about Bharatanatyam, participated in a movement workshop led by graduate students from the Dance Department, and attended a talk given by Ranee and Aparna Ramaswamy. Prins comments, “UMS went out of their way to introduce the artistic directors to the class.” For their written response to the performance, Prins asked students to formulate an interpretation of the work by drawing on information from the preparatory readings and workshops as well as on their direct experiences in the theater. “It was an opportunity for some students to say, ‘I don’t know all I need to know to make sense of this,’ and to think critically about what they were missing,” explained Prins.

Photo: Ragamala Dance Company. Courtesy of the artist.

For Madhumita Lahiri’s Introduction to Indian Cinema: Bollywood (English 375), Written in Water extended the students’ investigation of a culture’s ideals around the body and movement. The performance allowed an additional perspective on Indian dance, augmenting students’ study of movement vocabularies in films. Lahiri’s students learned Bharatanatyam’s hand and foot movements and basic postures and she finds that, since the performance, students are noticing references to Bharatanatyam in the films they watch. Written in Water also became a lesson in looking. Lahiri notes, “Many of my students are on dance team, but the concert dance experience is new. Even students with a South Asian background, who know Bharatanatyam, don’t know the ‘codes’ of concert dance. There are choreographic layers, in addition to production layers like the projected artwork.” The class also found that unlike films, “There are no close-ups and no focus on the soloists. The camera isn’t there telling you what to watch. That was part of our classroom discussion—What did you notice? How did you know what to watch?”

Photo: Professional artist photograph of Ragamala Dance Company

Leslie Hempson’s Islam at Sea: The View from the Indian Ocean (History 195) examines how Islam spreads, asserting that it is an oceanic tradition, transported through commerce and navigation. Written in Water provided students the opportunity to consider some of the course’s themes through the medium of performance. For example, the course examines Sufism, a primary mechanism for the spread of Islam in South Asia, and especially its experiential elements; Sufism stresses an interactive relationship with God, often mediated through music and dance. The incorporation of Sufi text into the performance allowed students a different sort of inquiry into this theme. Their assigned responses to Written in Water focused on experiential elements—how it looked, how it sounded, how it made them feel. “Another major concern of the class is movement, movement of people and ideas,” says Hempson. “We can see how portable so many traditions are. Ragamala based in Minneapolis is an example; the tradition comes from South India. It helps us think about how art changes as it moves.”

In Sara McClelland’s Approaches to Feminist Scholarship in Humanities and the Social Sciences (Women’s Studies 601/602), first-year graduate students investigate feminist approaches to research practices that are used across the Humanities and Social Sciences. These include embodied methods along with more familiar ones like reading, listening, and counting. Written in Water provided an opportunity for McClelland’s students to consider ethnographic participant/observer practices, performance, and spectatorship as modes of research. She notes, “A lot of students aren’t accustomed to thinking about performance as inquiry. Most had never imagined performance’s potential as scholarship.” Now McClelland asks, “Where are your bodies in your research?” For their final projects, using methods from the course to investigate a research question, most of her students are planning to incorporate embodied practices. McClelland considers UMS performance an important part of her course, not only pedagogically—because it allows students to encounter sources other than text—but also socially. Most of her students had never heard of the Power Center and were excited to learn about UMS programming, especially the No Safety Net series.

Are you a U-M faculty member who would be interested in bringing your students to a UMS performance? $15 Classroom Tickets are available for students and faculty in courses that require attendance at a UMS performance. To learn more about how to work with UMS, email Campus Engagement Specialist at skfitz@umich.edu or check out our new guide How to Integrate a UMS Performance into Your Course.

Veronica Dittman Stanich writes about arts-integration in the university for UMS, and researches it for the Alliance for the Arts in Research Universities (a2ru). She also teaches writing about dance and performance, and holds a PhD in Dance Studies.

Student Spotlight: Johnny Mathews at Urban Bush Women

This post is part of a series of posts by students who are part of our 21st Century Student Internship program. As part of the paid internship program, students spend several weeks with a company that’s on the UMS season.

U-M student Johnny Mathews was paired with Urban Bush Women in Summer 2017. Urban Bush Women perform in Ann Arbor on January 12, 2018.

Photos: Group photo of all Urban Bush Women’s Student Leadership Institute (SLI) participants at the end of the Culminating Performance

Photos: Group photo of all Urban Bush Women’s Student Leadership Institute (SLI) participants at the end of the Culminating Performance

This summer, thanks to UMS’s 21st Century Artist Internship program, I was able to spend two months in New York City and had experiences that surely changed my life in known and unknown ways. I was placed within, 33-year-old dance company, Urban Bush Women (UBW), a Brooklyn-based dance company dedicated to sharing stories of the African diaspora and committed to enacting social change through dance and workshops. Most of my time with the company was focused on preparing for UBW’s Summer Leadership Institute (SLI). I assisted in administrative work to help the administrative staff as they readied all that goes into having a long workshop for over one hundred participants and staff.

This ten-day intensive program was entitled: You, Me, We – Understanding Internalized Racial Oppression and How It Manifests in Our Artistic Community. SLI consisted of dance classes that was accessible for every body–type, size, ability– to do and be involved in. These dance classes were used as ways to share different African-American dance traditions, such as the ring-shout, the Second Line, and J-Setting. Dance was just a small portion of the day, however. The first seven days of the program were focused on discussions about racism and how it manifests in our community, as well as how and what we can do as artists to help combat racism.

This first meant that we had to truly understand the systems and operations that have been in place in our country that have systematically oppressed marginalized communities. These workshops were led by an organization that works to undermine racism in communities around the country: The People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond (PISAB). I learned so much from these workshops, and my frame of reference was completely shifted with respect to how I think and talk about racism in America. I still find myself processing a lot of the information that was presented and discussed to this day.

Photos: On left, Vincent Thomas passionately leading class at SLI. On right, volunteers who helped with Black Velvet Fundraising Performance Art Event at the 14th St Y.

For the last few days of the program, the focus shifted to actually creating a culminating performance that would be presented to an audience. The way this was created was really special and something that I had never been a part of before. Instead of having one leader or creator heading the creative process, the show was created very democratically. It started with the entire community coming together and sharing what they bring to the table; whether it be music, singing, theatre, poetry, sound and light design, dance, etc. Then the performance was created by the people and allowed for everyone to showcase their best talents and abilities. Seeing the entire community come together to build upon each other’s talents was inspiring and made me think about how this can be replicated in all aspects of art making.

Though this culminating performance seemed to be the culmination of my weeks of work, there was one more part of my internship: I was able to accompany the dance company on a four-day tour to Akron, Ohio. This was a truly immersive, educational experience. I was able to follow the co-artistic directors, the company members, the company manager, and the technical director as they traversed all that comes with a quick, one-stop tour. This tour was presented by the Heinz Poll Summer Dance Festival and was composed of two performances, a master class, and a post-show talk back. Something really interesting to see was how adaptable everyone had to be on this tour.

UBW was performing excerpts from Walking with Trane and portions of their 30th Anniversary Collage, two works that the company was not currently working on. Therefore, the dancers had only one or two rehearsals together in Akron to put these works back together. Not only were they putting it together, but they were rearranging the works while we were there, with everyone adapting to the changes perfectly. I was allowed an insider’s look into how a world-class dance company interacts with a presenter, a new community, and each other.

Photos: On left, John Mathews pictured with the New York skyline from the beaches in DUMBO, Brooklyn. On right, participating in Sidra Bell’s Summer Module 2017.

I grew so much as a person by being an intern with UBW. Not only from all the work I put in for the company and the insights I gained, but also because I was able to live in New York City for two months and was afforded opportunities that I would never have been able to have otherwise. While I was in the city, I attended Sidra Bell’s Summer Module, a week-long dance intensive that connected me with a community of New York based dancers; I saw so many different kinds of performances, such as Dearest Home by Abraham in Motion, Onegin by American Ballet Theatre, Hamilton, and many more; I assisted Shamel Pitts and Mirelle Martins in a fundraising event for their world tour of Black Velvet; and I was simply able to feel settled in while living in New York City. I had a summer immersed in all facets of the art-making process and am so grateful to UMS for the opportunity.

See Urban Bush Women on January 12, 2018.

Going Gaga for Gaga

Photo: Batsheva Dance Company. The company performs Last Work January 7-8, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

On January 7-8, Batsheva Dance Company bring their new work Last Work to Ann Arbor. Led by critically-acclaimed artistic director Ohad Naharin, this piece is devised using the Gaga movement language, the movement form for which the company and the director are best known.

Based in Tel-Aviv, Batsheva Dance Company was created by Martha Graham and Baroness Batsheva de Rothschild in 1964. The company has evolved its movement style from the Graham-based technique into the Gaga movement language, integrating emerging Israeli choreographers throughout its lifetime before Ohad Naharin took the helm in 1990.

Bodybuilders with a soft spine

Ohad Naharin created the Gaga movement “language” in the 1990s during his first few years as artistic director at Batsheva. Partially inspired by his observations of existing techniques as well as a non-dancing Batsheva employees request to learn how to dance, Naharin created Gaga in response to the rigid perfectionism that permeates some dance styles. He describes this type of perfectionism as a “deadly burden,” and the antithesis to accessing true movement and physical expression.

All movement stems from sensation in Gaga. Movement is a sensual experience: Dancers learn to love their sweat, the burning of their muscles, and their interior sensory experiences as they move. Gaga teaches dancers and movers to focus on the rhythm of their bodies, not the music. Focusing in this way helps movers find their inner ambition, discover themselves instead of focusing on dance as an external experience based on learned techniques.

Naharin uses Gaga to teach his dancers how to be “body builders with a soft spine.” He works to break dancers free from their technique, which is necessary as a structural component of dance training but also can restrict dancers from finding movements not found or prevalent in particular dance styles. In fact, while creating choreography Naharin discourages dancers from using improvisation, which he says often lures dancers back into their habitual movement patterns.

Gaga comes to the University of Michigan

Naharin’s movement language has spread to dance companies across the world, partly because of Batsheva alumni like Bsomat Nossan. Nossan was a guest lecturer in the Dance department at the University of Michigan in the Winter 2016 semester.

We spoke with U-M BFA Dance students Johnny Matthews and Kasia Reilly, both students who have studied with Ohad Naharin or his company members.

Reilly says that Gaga is not so much a technique as a “vehicle to dance with; it increases sensitivity to the conversation between one’s inner kinesthetic experience and the external feedback one receives while dancing.” For Matthews, Gaga is an essential part of his dancing education. Matthews decided to study with Ohad Naharin and Batsheva after seeing L-E-V Dance Company, a dance troupe started by a Batsheva alumna Sharon Eyal. (The company performed at the Power Center in Ann Arbor as part of the 2015-16 UMS Season.) “I was amazed by the raw power these dancers had,” he says. “The way they could manipulate their bodies into unimaginable shapes, then return to a neutral state in an instant.” Gaga was instrumental in helping Matthews unlock the opportunities within his body, to move in ways he never did before by looking inward instead of simply “putting movement onto [the] body.” This method helped Matthews to find new ways to approach movement even in technical or shape-driven styles like ballet.

According to Reilly and Matthews, Gaga sessions can vary widely from instructor to instructor. The rules are simple: “No mirrors, no late entry, no one can watch class, and you never stop moving,” says Matthews. Gaga movement is centered around the idea of “floating” through space, meaning your body is unencumbered by gravity and thus is available to move in limitless ways. These sessions involve exercises with instructions such as “draw circles with different body parts,” “imagine the floor is getting hot,” or “become a string of spaghetti in hot water,” and other sensory-based exercises to help dancers access unfamiliar movements. Gaga teachers encourage students not to miss class because “Gaga class is all about building tasks on top of each other to push the limits of how much information your brain can process at one time,” Matthews says. If students are feeling slow or low-energy, they may work at their own pace, working at “40%, 30%, 20%, or float,” but they must never be stagnant.

Gaga movement language creates a way for both dancers and non-dancers to access new movements. According to Matthews, Naharin was severely injured at the time he created Gaga and devised the language in part to rehabilitate himself. Gaga pedagogy is broken into Gaga Dancers and Gaga People. Non-dancers are actively encouraged to explore the technique, and Gaga People classes are created to train people to be better attuned to their own body and their own needs.

Naharin’s influence can be felt globally. Batsheva alumni such as above-mentioned Sharon Eyal (founder of L-E-V Dance Company), Andrea Miller (Gallim Dance Company), and Daniele Agami (Ate9) have used their artistic prowess to spread Gaga throughout the world. Ohad Naharin’s movement language has become one of the most popular contemporary dance philosophies of today. “I would call it almost uncommon now to meet a dancer who hasn’t taken at least one Gaga class before,” says Reilly, adding “the rawness, athleticism, and sexiness of his works are addictive to watch,” and the success of his company has lead to an uptick in mindfulness-based somatic movement work in the dance community.

The opportunity to see the company where it all began awaits. See Batsheva Dance Company’s Last Work in Ann Arbor January 7-8, 2017.

On Being African at the University of Michigan

Moment in portrait of myself as my father. Photo by Gennadi Novash.

Nora Chipaumire’s portrait of myself as my father is a piece of many origins. All aspects of Chipaumire’s identity as an African, a woman, a black woman, an African woman, and an African-American woman seep into her work. In this “love letter to black men,” she explores the complex tangle of conceptions, stereotypes, expectations, vulnerabilities and strengths of the black African male.

Zimbabwean influences, unique venue

A dizzying combination of Zimbabwean and African dance traditions, garb, and music help to tackle these big questions. Traditional Zimbabwean music rooted in polyrhythmic beats combines with Zimbabwean dance, an art form which requires a considerable amount of strength and agility to perform. Chipaumire uses these tools to celebrate the strength, resilience, and inherent defiance of the black body. She fuses her Zimbabwean heritage with her contemporary dance training to create this piece. Wearing traditional African gris-gris (a talisman used in Afro-Caribbean cultures for voodoo) with football pads, Chipaumire explores the black male at the crossroads of two cultures and identities.

Nora Chipaumire in portrait of myself as my father. Photo by Elise Fitte Duval.

The piece is set in a boxing ring and will be performed in at the Detroit Boxing Gym, where a program to support kids living in Detroit’s toughest neighborhoods is based and focuses on helping young black males find fruitful after-school activities to grow and develop real-life skills with positive role models.

It is not only a fitting location for Chipaumire’s exploration of black masculinity in a postcolonial world but also serves as a perfect setting for her vigorous, high-energy performance. Chipaumire has also spoken out about the brutal policing of black sexuality and masculinity, and celebrates her heritage through her art.

On Being African at the University of Michigan

African students at the University of Michigan have a unique perspective on the challenges and stereotypes Africans experience in America. Tochukwu Ndukwe, a Nigerian-American kinesiology student born in Nigeria and raised in Detroit, spoke about how his identity as a Nigerian-American student informs his experiences at the University of Michigan. In a school that is overwhelmingly white (a mere 4.4% of the population is Black or African-American), he immediately stands out.

In fourth grade, Ndukwe met a Nigerian student who embraced his culture unapologetically. This student was unafraid to educate other students about why he brought a different kind of lunch to school, or the differences between his how his parents raised him in an African household. Ndukwe was inspired by this classmate, but did not to truly publicly embrace his culture until high school. Torn between wanting to fit in with other black students and wanting to celebrate his culture in public, Ndukwe was both surprised and excited by the strength, unity, and pride of African students at the University. He now serves as president of the African Student Association (ASA), an organization that arranges cultural shows, potlucks, and mixers with other ethnic organizations on campus. Their flagship event is the African Culture Show, a massive celebration of African music and dance that packs the Power Center every year. This year’s show is titled Afrolution: Evolution of African Culture, an inquiry into the future of Africa by African students.

Ndukwe lauds African music as a crucial tether for African students to relate to the culture in their home country. He says that music allows African students to connect with their culture no matter where they are, which is especially important in Ann Arbor, which lacks the music, values, and language of their home countries.

“African music and dance are becoming more and more American,” Tochukwu says. “People there look up to America, they want to be American. African artists are beginning to collaborate with American artists, and I’m like ‘No, don’t lose your culture! It’s so rich!’” Africans are bombarded with American media and feel an increasing pressure to conform music and dance styles to that of American–particularly black American–culture, Ndukwe says.

A very loaded question

We begin discussing gender norms in Nigerian societies (he says many of the Nigerian gender norms are found throughout Africa) and a broad smile spreads across his face. “Oh, boy…you’ve asked me a very loaded question. I don’t even know where to start.”

He says, “African men are expected to be the breadwinners. They’re supposed to be strong, stoic, devoid of vulnerability. They are expected to be the disciplinarian of the family while women are expected to stay home…cook, clean, care for the children.” He explains that the expectation for men to be “macho”, and “hypermasculine” oppresses women, and that the division between genders prohibits women from getting an education and becoming financially independent.

“Mental health hasn’t even begun to be a topic in the general cultural discourse. There’s no such thing as depression, as anxiety for anyone, let alone men. So many men suffer in silence because of it.” As pressures mount for men to be sole breadwinners, disciplinarians, protectors of the family–stoic and strong–many men are subsequently unable to express their emotions with the women they care about. Ndukwe’s background as a Nigerian-born man raised by Nigerian parents tightly bound to their culture informs his relationship with women today. On a personal note, he says that he struggles to express his affection with his significant other. This leads to gaps in communication and rifts in his relationships that are often difficult to repair.

portrait of myself as my father comes at an especially important time. As the consequences of the narrow and stereotypical perception of black men enter the mainstream consciousness, this piece opens the door for discussion.

How does the representation of the black body impact the perception of self as a black woman, an African woman, and an American woman? How has colonialism seeped into the treatment of the black performing body?

Nora Chipaumire asks and investigates these questions in portrait of myself as my father.

See the performance November 17-20, 2016 at the Detroit Boxing Gym in Detroit.

Behind the Scenes: Dorrance Dance

Ever wonder what it’s like to get the stage ready for a dance performance? Dorrance Dance Lighting Supervisor Serena Wong lets us in on the magic.

See Dorrance Dance in Ann Arbor October 20-21, 2016 at Power Center.

Unique Venue: Downtown Boxing Gym

November 17-20, 2016, UMS presents choreographer Nora Chipaumire’s portrait of myself as my father in Detroit at the Downtown Boxing Gym. Find out more about the amazing youth program at Downtown Boxing Gym.

Learn more about the performances of Nora Chipaumire’s portrait of myself as my father November 17-20, 2016.

The Lost Art of Writing Love Letters

Observations from Kyle Abraham’s Residency work with Michigan LGBTQ Youth

Choreographer Kyle Abraham. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Never before have I found myself in a group of “strangers” whom I felt I actually knew quite well. We were sitting in a large circle in a white, bright room in the Affirmations center of Ferndale, Michigan, roughly 40 minutes out from Ann Arbor.

The group was richly diverse in age, style, perspective, and gender. Many in the group were young people from the Metro Detroit area who identify as LGBTQ. Others in the group were UMS staff and adult leaders and volunteers of the center. Regardless, after just a few days of experiencing workshops together under choreographer Kyle Abraham’s lead, participants were comfortable with sharing something they loved about the people sitting next to them. At the beginning of our first meeting earlier that week, we had shared only our names and preferred gender pronouns. In the time between, Kyle and some of his company members had created a transformative, interactive experience for their dance research and for the hearts of each participant.

Kyle’s New York-based contemporary dance company Abraham.In.Motion has a mission to “create an evocative interdisciplinary body of work.” To help deepen the development of Kyle’s newest work, which he currently calls Dearest Home, UMS hosted the choreographer and four of his company members for one week.

The artists spent nearly ten hours at Affirmations, where they shared the progress on their choreography, asked for feedback, led discussions on the core themes of the work, and even taught some movement to the group who had gathered to participate. As a former 21st Century Artist Intern with UMS, I was lucky enough to sit in,observe, and absorb. (My colleague Sophia Deery spent a whole summer with Kyle in the same program. You can read about her experience.)

To start, Kyle led an open conversation about healthy relationships, a vulnerable topic but a productive discussion. The group ultimately came to important conclusions, for example, happiness is an identifier of love, not a product of love, which led us into our next activity. Kyle directed us to a table full of magazines, color pencils and markers, envelopes, scissors, glue sticks, and more. He asked everyone to write a good old-fashioned love letter, a gesture he described as a lost art. He turned on a playlist and let all of us, including his company members, sit together and work on our small expressions of love. We wrote love letters to friends, romantic interests, and even ourselves. Some words that were thrown around in the reflective discussion that followed the activity were “insecurities, easy, hard, weird, nice.”

Kyle’s playlist continued filling the room as we transitioned into our next activity, which involved huge, white pieces of blank paper taped to the walls. Kyle asked us each to recall some of the words that were used in our first group discussion and to visualize them, as literally or as abstractly as we wished, on the wall. Within minutes, the walls were full of “blooming, touching, dream, cuddle, risk,” and more.

Kyle’s dancers then shared a trio of choreographed movement that they had worked on in the dance studio that week. More word associations were thrown out from the group in response to the choreography. Some of the group saw petals in the dance, others saw comfort and support, and others saw the healing powers of touch and love.

The next excerpt of choreography, this one a duet, got drastically different reviews. First danced for us in silence, this duet was associated with “anxiety, separation, unsettling.”

Kyle asked the dancers to execute the same choreography again, this time to music he had used while creating it. He explained to the group the significance and influence of this music on his choreography. He shared that he sometimes spent years working on a playlist for a dance piece before actually beginning his work on the movement, and the playlist doesn’t necessarily become that dance’s sound score, but may be used otherwise in the final product. For example, he had the playlist used to create the dance piece Radioshow as pre-show music at the theater, music that played as the audience filed in. The dancers felt that their silent run-through of the choreography made them more dependent on each other’s timing and left a lot of decisions to their creative imaginations. The run with music, alternatively, provided them with more context and drive. Some members of the group preferred the intimacy of the silent run-through, and others appreciated watching the influence of the music.

The discussion on music continued as Kyle asked us each to create our own Love Playlist for TODAY by gathering a collection of music that was relevant to our feelings in that exact place and time. I thought about all the channels of love I felt in that specific moment: love for family, friends, self, dance, people, romantic love. I began jotting down as many relevant songs as came to mind. We each shared highlights from our playlists with each other and bonded over mutual musical interests. I remember smiling and shaking my head in disbelief at the fact that just from hearing some song titles that came to mind when people thought about love, I could get a strong context for how they are doing and feeling in their personal lives.

Kyle then showed videos of his previous works, including Radioshow and Watershed, a piece that was presented recently through UMS. He explained that within his creative process, he has also used his playlists to improvise movement, and then his dancers learned choreography by studying videos of his improvisations.

He also teaches the dancers new phrases bit by bit, as he invents on the spot, and asks dancers to “catch what they can” throughout his improvisation. He showed us an example, as he improvised and then Penda, one of the dancers, created her own adaptation of that phrase. Suddenly, the company had a multiplication of movement material to work with and develop furthermore for the growing piece.

Another strategy that Kyle uses to generate movement in this piece is retrograding a phrase of choreography that already exists. This essentially looks like the same movement, just done backwards, as if on a rewind function. Additionally, Kyle uses action words like “dive, jump, snake, slide, and twerk” to direct his dancers in improvisational exercises to create new movement. He is also inspired by simple, human gestures; pedestrian movements that we all see every day like a nod of the head or a wave of the hand. The dancers showed examples of movement created from all of the above strategies. We even got to learn an excerpt of the gestural phrase and get up and try dancing across the room to some of Kyle’s action words.

Kyle later returned to the topic of our individual Love Playlists. He instructed the dancers to show us some choreography while each of us listened to a song from our personal playlists. Some participants were amazed at how musical the dancing was, even when the dancers themselves could not hear our individual songs that were playing through our personal earbuds and headphones.

This connection between the music and the dancing, both revolving around the theme of love, inspired us to create album covers for our playlists. I looked over my colorful album cover, my collage of words in my love letter, my playlist of happy and sad love songs, and I realized that my own experience with the themes that are fueling Kyle’s new work channeled through my own life in so many ways over the course of that week. The majority of the room had the same experience.

Kyle’s new piece seems to be a love letter in itself. It is full of vulnerability and honesty. It is inspired by the pieces of his personal life that are closest to him: his history, his home, his identity. It explores and celebrates just how human the art form of dance is. I felt validated as a dance artist because I could see the change in the participants of Kyle’s residency. Their closing remarks revolved around a majority opinion that they now saw dance as relatable, emotional, and human. This new work is sure to be a love letter to that sentiment.

Behind the Scenes: Dance Activities

Camille A. Brown & Dancers performed Black Girl – Linguistic Play on February 13, 2016, and the dancers also participated in various community activities including a free Breakfast Download post-performance discussion and all-levels You Can Dance workshop. UMS also hosted a panel celebrating 25 years of the Dance Series at UMS.

What some of the participants thought about their experiences:

Photo moments from the weekend:

Quotes from the weekend:

“I saw myself in this play. The way the dancers expressed themselves in each scene seemed like flashes of my own life.”

-Christina DeBlanchi, Black Girl: Linguistic Play audience member

“Being in college means I have to be an adult who is focused on reading and writing. It was really fun to see something equally, or even more important, happening on stage. It brought me joy. And these experiences give me the opportunity to learn more by exploring my self, instead of reading about others.”

-Alexis Lesperance, U-M Residential College student

Interested in more? Learn about our community education programs.

25 Years of the UMS Dance Series

UMS celebrates 25 years of the UMS Dance Series in 2015-16 season. It’s been quite an adventure.

Interested in more? Explore dance through our archives.

Watching L-E-V and Chucho Valdés: Hypnotized

Editor’s note: Helena Mesa is a poet and one of our 2015-2016 artists in residence. As part of this program, artists in residence attend UMS performances to inspire new thinking and creative work within their own art forms. Helena saw LEV, the dance company led by former Batcheva dancer and choreographer Sharon Eyal, and Chucho Valdés, the legendary Cuban pianist. Below is her response to the performance.

1.

October arrived with techno beats and L-E-V, the dancers like liquid as they pulsed across the Power Center stage. Dressed in black body suits resembling latex, the dancers slid through space, but before I knew it, Sara, the 13-minute dance, ended, the lights stunned the auditorium, and our voices rose in response—each murmuring to the next. I’d come to the performance as part of the UMS artist in residence program, and suddenly, I wasn’t sure how I was going to write in response to dance.

It was later, during Killer Pig, the longer second performance, the dancers dressed in earthy tones, that my mind shifted, and instead of thinking about how to think about what I watched, I gave myself over to the music, to the conversation between body and sound. The dancers were hypnotic, shifting from ballet to modern dance, the forms blending, so I couldn’t tell what was what—what was classical, what was modern, what was the beauty of a body, and what was the beauty of the choreography. Their movements felt raw, one body’s motions echoing another’s, at times coming together, at times breaking apart, until one of the dancers broke off into her own, and the music, too, broke, into sharp sounds that almost hurt in its emotional cacophony.

2.

And then, November arrived, and on a sunny Sunday afternoon, I walked through downtown to the Michigan Theater. The streets bustled. Folks strolled, enjoying the unexpected mild fall. Entering the theater to see Chucho Valdés: Irakere 40, I was surrounded by Spanish, the Cuban kind, the accent familiar, the words turning my ear in ways that carry me home. I settled into my seat, chatted with the woman beside me, fingered my program, and when the show finally began, the piano and bass and drums cracked the crowd’s murmurs. The notes spoke to one another. And the horns talked back.

And with time, so did we. We raised our hands and clapped to the beat, we stood and swayed our hips at our seats, and when the singer asked us to sing, we sang back, pio pio pio, and later ella, and suddenly, I found myself again hypnotized, giving myself over to the performers, but also, giving myself over to a familiar story: My father sitting on the couch reading the paper, my mother pulling him up from the couch, and the two giving themselves over to the piano and bass and horns of a Cuban big band, and dancing the way Cubans dance—with a joy to be alive.

That evening, I walked out into the twilight and felt the eerie feeling of being pulled out of myself. The music was still with me, and I felt that familiar feeling we often experience when we’re young—the desire to stay with the crowd for as long as we can, to feel part of something larger, and a strange sadness to walk off alone, the music still lingering. A horn to the chill in the air. A beating drum to each step toward the parking garage. The step back and half-turn up the stairs. My own humming.

3.

When I was first learning to write, I wrote thick lyric poems that never made sense, and instead of thinking about how to write a clear narrative that a reader might understand, I focused on the poems’ music. At the time, I’d never studied meter or rhyme; I’d never thought about the structure of the line, but I wanted my poems to mimic Arturo Sandoval, an early member of Irakere. I’d listen to “A Mis Abuelos” (“To My Grandparents”) again and again, and then I’d color-code my poems, trying to find a way to mimic not only the rhythm, but the shift in tone between a solitary trumpet that suddenly breaks into a congregation of big band sounds—horns, piano, guitars, and conga drums.

Thankfully, I’ve lost all those badly written poems, but now I realize that I was trying to find a way to break open a poem, to evoke an emotion I didn’t know how to express, to say something unexpected and meaningful, much like James Wright captures at the end of “A Blessing”: “Suddenly I realize / That if I stepped out of my body I would break / Into blossom.” I often, jokingly, tell my students that if I were ever to bear a needle long enough to get a tattoo, I’d print Wright’s lines along the inside of my forearm, as a reminder. Those transformative moments happen so rarely. You can’t force them—they just happen. Nonetheless, I want a poem to transform me as a reader, much like L-E-V and Chucho Valdés transformed me as a viewer.

I do not yet know how L-E-V and Chucho Valdés will shape my poetry. I can picture how the lines of a poem might begin to move through the white stage of a page, and I can imagine how I can play with both traditional rhythms and modern speech. And I know I want to find a way to layer different sounds and voices, like Chucho Valdés weaved tango, funk, and Afro-Cuban rhythms. But right now? I’m hung up on hypnotism, how the music compelled and enthralled me. How I couldn’t turn away from the elastic muscles and mirrored movements; I couldn’t turn away from instruments stretching and teasing until it seemed the song might break. In the dark, I leaned forward, wanting to memorize every movement and sound.

Photos are courtesy of the artists.

Free Dance Workshops for All

Lots of happy faces at our You Can Dance workshop and Breakfast Download Discussion event this weekend.

Photos by Sharman Spieser.

Interested in more? See the full listing of upcoming free activities open to all levels.

Dance Renegade: Choreography of William Forsythe

Editor’s note: As part of the UMS 21st Century Artist Internships program, four students interned for a minimum of five weeks with a dance, theater, or music ensemble part of our 2015-2016 season. Meri Bobber is one of these students. This summer, she was embedded with Hubbard Street Dance Chicago.

Below, Meri shares her travel stories with the company in advance of their return to Ann Arbor on October 27, 2015.

Photo: Moment in “Quintett” by choreographer William Forsythe. Photo by Cheryl Mann.

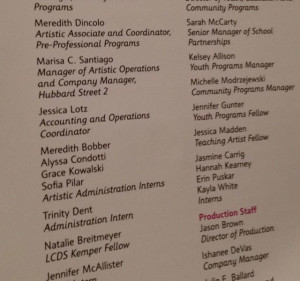

Meri’s note: My summer at Hubbard Street offered me some personal insight and experience with the work of world-renowned choreographer, William Forsythe. I met him and heard him speak at the company’s annual gala this June, researched his career as I helped write visa applications for his German restagers, experienced being in rehearsals with him and the Hubbard Street dancers, and conducted interviews about his work with Hubbard Street’s Meredith Dincolo, Glenn Edgerton, and Kevin Shannon. On October 27, Hubbard Street Dance Chicago brings a production of Forsythe’s choreography to Ann Arbor.

Forsythe’s History

American-born William Forsythe made his choreographic debut in 1976 after dancing professionally for companies including the Joffrey Ballet. He then went on to serve as the resident choreographer of Ballet Frankfurt in Frankfurt, Germany until its closing in 2004. He founded his own company, The Forsythe Company, with many of the same dancers and continues developing his work abroad.

Movement aesthetic

Forsythe is widely credited for radically rethinking and reinventing ballet. He uses balletic concepts such as épaulement (a type of shoulder movement) in many of his works, but infuses the foundational technique with new ideas and fresh contexts. His movement language explores the geometric possibilities of the body as it moves through space, challenges verticality, employs torsion and spirals, and explores lines, points, and curves. Hubbard Street’s Artistic Director Glenn Edgerton said in an interview this summer that Forsythe’s perspective and work “has changed the face of dance.” Retired Hubbard Street dancer Meredith Dincolo, now artistic associate and coordinator of pre-professional programs, added, “In classical dance and in contemporary dance, you can’t deny [Forsythe’s] importance.”

Forsythe as a collaborator

Forsythe’s work can be highly collaborative, academic, and technology-driven. He has developed his own computer software and improvisation technologies that explore geometrically influenced movement generation. Additionally, he has collaborated with The Ohio State University to create an interactive website which examines One Flat Thing, reproduced, one of the pieces that Hubbard Street will perform for our audiences. Forsythe’s work “made science and dance come together,” says Edgerton.

One Flat Thing, reproduced by William Forsythe from dance-tech.TV on Vimeo.

Creative process

Forsythe’s dancers are treated as essential collaborators throughout his creative process. On September 30, 2015, in a conversation with Hubbard Street’s Zac Whittenburg, Forsythe articulated that his choreographic process consists of giving his dancers the substantive ideas, shapes, tasks, and themes (the “what”). The dancers then bring these to life in the studio (the “how”). Those working to set the rep on Hubbard Street’s company are all dancers who participated in the original casts of the works. Glenn Edgerton believes the process of learning, rehearsing, and performing Forsythe’s choreography will “change and broaden [the Hubbard Street dancers’] perspective” on dance, influencing the rest of their careers. Hubbard Street dancer Kevin Shannon agrees. This summer, he said that he’s excited to focus on one choreographer’s work for several months, because especially with Forsythe, “it is all about the process.”

Future

Now 65, Forsythe is retiring as artistic director of The Forsythe Company and will soon be on faculty at the new Glorya Kaufman School of Dance at the University of Southern California. His educational efforts in America will begin to contribute to the propulsion of “what’s next” in American contemporary dance. The contemporary dance community of the United States is highly anticipating his return.

Forsythe in Ann Arbor

The William Forsythe program that Hubbard Street brings to Ann Arbor will restage three of Forsythe’s most impactful works: N.N.N.N., Quintett, and One Flat Thing: reproduced. This selection of works exemplifies Forsythe’s signature movement language while also proving his diversity as a choreographer as the three pieces vary greatly:

- N.N.N.N. is a quartet originally set on four male dancers. The HSDC restaging is challenging the role of gender and inter-gender relationships by substituting women into some of the roles. The choreography is precise and fearless and moves like mechanical clockwork. The dancers’ limbs intertwine and bounce off one another’s bodies as the group moves through space.

- One Flat Thing, reproduced was created in 2000, recreated on film in 2006, and was originally set on 14 dancers with 20 large, identical tables. The tables create grid-like negative space on stage, and the dancers maneuver over, under, and around this space in solos, duets, trios, and larger groups. The piece is a massive puzzle of visual and aural cues, and requires the dancers to pay explicit attention to one another’s timing. This is the kind of piece that’s always happening: if you blink while watching, you’ll miss something.

- Forsythe’s late wife inspired Quintett. Five male and female dancers move to exhaustion to the repetitive music of Gavin Bryars. The choreography exemplifies Forsythe’s geometric interests and explores grief by taking the dancers on a journey to a state of extreme physical fatigue. Hubbard Street dancer Kevin Shannon confirms that this is “one of the hardest pieces I’ve ever danced in my life… the state of exhaustion you reach creates a connectivity [with the other dancers] that you don’t see in other pieces. By the end, you have to let go and find a deeper place within yourself.” Meredith Dincolo describes Quintett as the most intimate of the works we’ll see, pairing well with the other pieces to give a “broad spectrum of William Forsythe’s work.”

Hubbard Street Dance Chicago returns to Power Center with an evening of works by choreographer William Forsythe on October 27, 2015.

Interested in more? UMS Artist Services Manager Anne Grove was once company manager of Hubbard Street Dance Chicago. Read our interview with Anne.

Talking dance with artists

Editor’s note: This post is a part of a series focusing on education and community engagement events surrounding our dance performances.

The 25th UMS Dance Series opened with L-E-V, an adventurous new ensemble of fiercely talented dancers, the culmination of years of collaboration between two Israeli creative superstars: Jerusalem-born Sharon Eyal (muse, dancer, and choreographer at Batsheva) and Gai Behar (who produces live music, techno raves, and underground art events in Tel Aviv).

Right after the performance, audience members could ask the artists questions about the performance as part of the post-show Q&A with artists. And the morning after the performance, dancers, audience members, and UMS staff got together for a post-show conversation, part of a new series of events called Breakfast Download Discussions (which feature bagels and coffee, too!).

Photos by participant Sharman Spieser.

Student Spotlight: Embedded with Hubbard Street Dance Chicago

Editor’s note: As part of the UMS 21st Century Artist Internships program, four students interned for a minimum of five weeks with a dance, theater, or music ensemble part of our 2015-2016 season. Meri Bobber is one of these students. This summer, she was embedded with Hubbard Street Dance Chicago.

Below, Meri shares her travel stories with the company in advance of their return Ann Arbor on October 27, 2015.

Assume nothing; be curious. This approach to artistry is something I learned from choreographer William Forsythe at Hubbard Street Dance Chicago’s Spotlight Ball on June 1, 2015. The glamorous night was a celebration of dance and highlighted the success and impact of Forsythe’s work, as the main company prepared to perform his choreography in its upcoming season. By the night of the gala, I was already a few weeks into my internship, but I carried this advice with me as I continued my summer in Chicago as a UMS 21st Century Artist Intern.

On left, the gala was held in a ballroom of the Fairmont Hotel in downtown Chicago. In this shot, dinner guests applaud as Artistic Director Glenn Edgerton introduces all the professional dancers of Hubbard Street. On right, Hubbard Street’s second company, comprised of early-career artists, perform a movement composition exercise to supplement the dance education of Chicago elementary school students.

My internship at Hubbard Street was structured so that I would rotate departments weekly for two months. This structure ultimately proved to be incredibly appropriate, as I saw firsthand that non-profit organizations require their employees to wear many hats, big and small, simultaneously, and to still maintain the ambition to learn on the fly, to jump in wherever he or she is needed. For example, the accounting manager at Hubbard Street also serves as IT. A former professional dancer of the company is now its Manager of Communication on the marketing team. When I joined the second company for a day of several dance outreach performances at Chicago area schools, the artistic director drove our van.

I practiced the same adaptability in my internship, beginning in artistic administration, where I was trusted with an important, ongoing project right away. One of the repetiteurs from The Forsythe Company was to come to Chicago and set three of William Forysthe’s works on the dancers for the performance Hubbard Street will bring to Ann Arbor in October. As an artist of German citizenship, he needed a visa for his work in Chicago. So, although I bounced around departments, I worked throughout my internship to research this repetiteur’s career, assemble resources, and write a coherent paper about him that proved the legitimacy of his trip and his work at Hubbard Street. I needed to present enough evidence to prove that he was the best and only man for the job. My supervisor worked closely with me on the project, taught me how to address the guidelines required by the government, and left me confident with a new, important skill. One of my highlights from the summer was the day that my supervisor informed me that the application had been accepted by the government. I met him in person later on, and his gratitude for my help with his application touched me. The work I had put into it proved successful for Hubbard Street and the Forsythe production.

On left, a shot from backstage of the Hubbard Street Youth Showcase where I helped the professional dancers of tomorrow make it on stage in time for their numbers. On right, I spent the week leading up to Hubbard Street’s Summer Series at the Harris Theater helping out at dress rehearsals backstage. It was a treat to find my name included on the Hubbard Street Staff listing in the program on opening night!

I switched responsibilities each Monday. I served in the marketing department, where I initially felt far out of my comfort zone but ultimately learned a lot in just five days; the youth education department, where I made great friends with other interns and helped the youth showcase recital run smoothly; backstage of the Harris Theater downtown, where I assisted Hubbard Street’s main company manager during a production that featured the work of resident choreographer Alejandro Cerrudo; and the development department, where I learned about external affairs and donor profiling, and helped out behind the scenes at the aforementioned gala. And that’s just to list a few!

On left, Hubbard Street marketed the Summer Series show with ads like this all over street kiosks downtown. It was fun to learn about such marketing strategies at work, then go see them in action on my walks to and from the theater. On right, Hubbard Street’s Resident Choreographer Alejandro Cerrudo signed my program on closing night of the Summer Series.

Following the internship, I stayed on for a third month to participate in the college-level summer dance intensive. This is a program I enjoyed thoroughly last summer as well. I was happy to have Hubbard Street’s artistic staff, alumni, and current dancers give me another satisfying amount of choreography to study and a technical kick-in-the-pants. The training tested my adaptability as a dance artist, connected me with talented young dancers from around the country, and filled gaps in my technique. It was a special experience to come to the building every day and spend 8 hours in the studios just as Hubbard Street’s professional dancers do. I studied ballet, yoga, Pilates, improvisation, Gaga technique, Horton technique, partnering, and a variety of diverse repertory excerpts that required me to dance with different qualities and intentions. I sweat. A lot.

On left, one of my closest friends from school, Lena Oren, came into Chicago for the summer intensive. Here we are dancing outside of Hubbard Street’s building, located on Jackson Boulevard and Racine Avenue. On right, the summer intensive concluded with an in-studio showcase, which offered my fellow dancers and me the opportunity to perform the repertory excerpts we had been studying for the past four weeks.

Beyond working and dancing at Hubbard Street’s building in the West Loop, I found that living in Chicago in the summertime was delightful. I grew up in Milwaukee, but hanging out on Lake Michigan’s lakefront never gets old. The Brown Line to Kimball route of the Chicago Transit System (the “L,” as locals call it) offers stunning views of the downtown Loop. The Taste of Chicago food festival, the Bean, Buckingham Fountain, and the city’s diverse and characteristic neighborhoods gave me much to do and explore. I had the priceless company of my older sister, who has lived in Chicago for more than a year now, and my best friend from school, who traveled from California to participate in the summer intensive at Hubbard Street with me. We ate out, walked the lakefront, hung around Clark Street, and attended street festivals, parades, and shows. I also used my weekends to attend dance classes and shows anywhere and everywhere in an attempt to acquaint myself with Chicago’s greater dance community.

I subleased two apartments during my three months there: one from a coworker at Hubbard Street, a 15-minute walk from the West Loop (where Hubbard Street’s building is located) in the quaint, historic Little Italy neighborhood of Chicago. The other sublet was more of a gamble. I lived with a stranger far uptown at Lawrence and Clark, a location that required me to learn how to navigate Chicago’s public transportation system each morning in order to get to work. In terms of my mysterious roommate, I actually got very lucky. I lived with a Chicago and dance enthusiast who showed me around the city, specifically the characteristic area of Lincoln Square, and has become one of my closest friends.

On left, Chicago skyline from the Brown Line train north to Kimball. On right, downtown loop of Chicago from the Brown Line train north to Kimball.

And so, both inside and outside of Hubbard Street’s building, my summer in Chicago fulfilled and excited me day-by-day. The pressure of having new assignments and needing to catch on to the operations of a new department at Hubbard Street every week honestly made me a little anxious on Monday mornings (especially during my week in marketing, an area in which I had no previous experience). The variety of choreography I studied during the intensive also required me to be flexible, in more ways than one! So I learned to adapt to the diversity in both the office and the studio, and to do my best with all that was thrown my way.

My to-do list throughout those three months was anything but monotonous. Every morning when I arrived at the building, I knew I could be asked to do just about anything to help make dance happen. I rolled out a marley floor. I organized video archives. I sifted through the dusty costume cage in the back warehouse. I wrote and I researched. I faxed and I answered phones. I brainstormed and I went to meetings. I ordered and picked up gifts for the choreographer on opening night. I ran the video camera at technical and dress rehearsals. I went to dance class and came back day after day with more sore spots and bruises. I cared to finesse the individual details and qualities of each piece I was taught. I tried assuming nothing and being curious all summer long, and it was an impactful approach to my working to bridge my student experience with becoming a professional.

On left, my Chicago-based older sister and I on a city bus. On right, Here I am at the Chicago Pride Fest, one of the many summer city activities I soaked up. Others included Taste of Chicago, the Blackhawks Stanley Cup Victory Parade, and free concerts at the outdoor Jay Pritzker Pavilion.

I left Chicago with a big-picture understanding of the many factors that make up the dance powerhouse that is Hubbard Street Dance Chicago. The organization offers more than 70 classes a week to the public, rents studio space out to dance projects and companies, holds special dance education workshops through The Parkinson’s Project and The Autism Project, educates young dancers in a variety of dance styles, practices dance outreach in Chicago’s public schools, develops early career artists through the second company, and produces professional shows that feature a wide range of choreography on national and international stages.

I spent one afternoon getting lost in Hubbard Street’s media room, which contains rehearsal and performance footage that dates back to the 1980s.

I now have a personal understanding of the effort, talent, teamwork, and dedication it takes to maintain such an umbrella for dance. The company dancers themselves are no less exceptional. They are thoughtful, articulate, versatile movers who appear almost invincible in the studio and in performance. When they grace the stage of the Power Center this October, you’ll see what I mean.

Hubbard Street Dance Chicago returns to Power Center with an evening of works by choreographer William Forsythe on October 27, 2015.

Interested in more? UMS Artist Services Manager Anne Grove was once company manager of Hubbard Street Dance Chicago. Read our interview with Anne.