The Perpetually Classical String Quartet

On left, Takács Quartet, and on right, Danish String Quartet. Photos by Ellen Appel and Caroline Bittencourt.

Later this fall, UMS will present performances by two renowned string quartets. In November, the upstart Danish Quartet will make their UMS debut, and the next month will see the return of the much-beloved Takács Quartet, who last performed to Ann Arbor audiences in April, 2013.

Both groups are presenting remarkably similar programs. Each will open with a Haydn quartet (both in C major, no less!), then perform quartet written in the last twenty years, and close with a Romantic quartet: Beethoven for Danish Quartet, and Dvořák for Takács. I have written previously about the way programs like these, which juxtapose older and newer string quartet compositions, demonstrate the history of the genre, namely the changes string quartet music has undergone from the Classical era to today and the recent past. At the risk of contradicting myself, I think the Danish and Takács Quartet’s programs more aptly demonstrate the way string quartet music has not changed over time. Truthfully, this kind of continuity is always present in string quartet music because the ensemble has not changed at all since Haydn wrote his first quartet in the 1760s.

Two violins, a viola, and a cello

By contrast, composers, from Beethoven to the students in the University of Michigan’s music composition department, constantly tinker with the orchestra to create different, seemingly new, sounds. Even the piano continued to evolve, mechanically speaking, throughout the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries. But, the string quartet has consisted of two violins, a viola, and a cello for over 250 years – it may be a perpetually Classical ensemble. Obviously, nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first century composers have stretched the sonic envelope of string quartet music to incredible lengths.

Black Angels by George Crumb

Devoted patrons of UMS’s Chamber Arts Series may remember the Kronos Quartet’s two performances from January 2014, when they performed, among other works, George Crumb’s Black Angels. Here, Crumb amplifies the quartet and asks its performers to yell and play various percussion instruments. This may seem like an irrevocable departure from the traditional corpus of string quartet music, but that is not the case. One of Black Angels’ more subdued movements features a heartbreaking quotation from Schubert’s String Quartet No. 14, “Death and the Maiden” – despite the experimental daring of Crumb’s sound world, Black Angels still contains a vibrant connection to the string quartet’s Classical heritage.

Arcadiana by Thomas Adés

Thomas Adés and Timo Andres, the living composers who will be performed by the Danish and Takács String Quartets, also maintain an awareness of the past in their music. Adés’ quartet Arcadiana, which appears on the Danish String Quartet’s program, features a potent allusion to one of Franz Schubert’s celebrated art songs, Auf dem wasser zu singen. Here, Adés interpolates quotations from Schubert’s song with his own musical material in a manner that contemplates what Adés observes as the most important theme of the original song’s texts: vanishing time. Accordingly, this movement of Arcadiana is strikingly characterizes by the sense of temporal unevenness; the quartet’s members do not wholly come together until the beginning of the subsequent movement. Although it has seven labeled movements, Arcadiana is composed very fluidly, and typically performed so that each section into the next without interruption. Similarly, though “Auf dem wasser zu singen” is the only part of Arcadiana to make an explicit reference to nineteenth century music, the rest of the work clearly expresses a kind of refracted anachronism that draws heavily on traditional compositional precedents. Much of the work is typified by active gestures and fleeting melodic and harmonic ideas, except for the penultimate movement, “O Albion”, which is a stunningly simple and beautiful statement in counterpoint.

An interview with Timo Andres

Timo Andres’ Strong Language, which will be played in between Haydn and Beethoven on the Takács Quartet’s December program, is more of a mystery because it has not yet received its premiere performance. However, Andres discusses the work at length on his website, describing it as an exercise in musical economy: “Strong Language has three movements and exactly three musical ideas.” Andres is also a renowned pianist, who frequently performs standard repertoire alongside his own compositions and those of other living composers. Thus, it seems likely this new work for string quartet will possess some kind of grounding in Classical music’s tradition. Certainly, this is the case in Andres’ last quartet, Early to Rise (2013), which, like Arcadiana, makes allusions to nineteenth century German art song (though, Andres’ work references Schumann, not Schubert). Per Andres’ description, Strong Language indeed seems to embrace numerous traditional compositional techniques, though its final movement features atypical instrumental sounds, such as scrapes and knocking.

Nevertheless, it is likely Strong Language, just like Arcadiana, will provide further evidence that the string quartet, as a genre and ensemble, is perpetually Classical. Even the purported noise elements in Strong Language’s closing movement are nothing new – George Crumb’s aforementioned Black Angels features similar effects and is forty-five years old.

Of course, the consistency in the string quartet and its repertoire I point out here does not represent a weakness for the ensemble, but, rather, an incredible strength. To support the expression of so many different composers over 250 years of Western musical history with the same instrumentation tells us a great deal about the enormous value of the string quartet as a medium. Be sure to consider the enduring strength of this musical tradition when it is on full display in the surely masterful performances the Danish String Quartet and Takács Quartet will share with UMS audiences in November and December.

The Danish String Quartet performs on November 6, 2015, and the Takács String Quartet returns on December 6, 2015.

Interested in more? Garrett Schumann is a regular contributor to UMS Lobby.

Artist Interview: Composer Gabriela Lena Frank

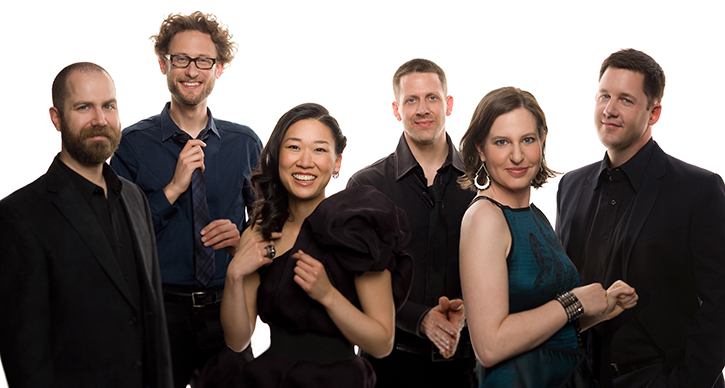

The Sphinx Virtosi, who’ll perform with composer Gabriela Lena Frank on September 27, 2015. Photo by Kevin Kennedy.

The Sphinx Virtuosi, led by the Catalyst Quartet, is one of the nation’s most dynamic professional chamber orchestras. Comprised of 18 of the nation’s top Black and Latino classical soloists, these alumni of the internationally renowned Sphinx Competition come together each fall as cultural ambassadors. When they perform in Ann Arbor on September 27, their program, entitled “Inspiring Women,” will focus the spotlight on female composers and works inspired by great women.

Composer, pianist, and U-M alumna Gabriela Lena Frank will perform the world premiere of her new concerto with the ensemble, co-commissioned by UMS, the Maxine and Stuart Frankel Foundation, and Linda and Stuart Nelson, among others.

Composer and UMS Lobby contributor Garrett Schumann recently chatted with Gabriela Lena Frank about the new concerto, working with Sphinx, and returning to Detroit area for the first time after completing her graduate degree at the University of Michigan over a decade ago.

Garrett Schumann: What can you tell us about the piece that you will be performing with the Sphinx Virtuosi?

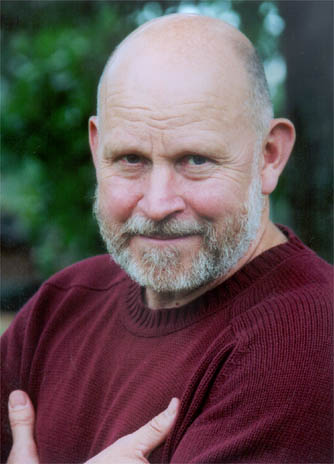

Composer Gabriela Lena Frank. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Gabriela Lena Frank: This will be the premiere, a UMS co-commissioned work for piano and string ensemble. Although technically the commissioned piece is a piano concerto, I don’t see it that way. The piano does have a central role, but I always wanted it to be something that would be believable as, say, a piano quintet. To that end, the strings are important as the piece has that chamber music kind of feel to it. So, that’s the first thing.

The second thing is that like a lot of my work, this piece draws inspiration from Latin American folk idioms. The name of the piece is Cuentos Errantes, which means “wandering stories.” It is inspired by the utopian concept of mestizaje as envisioned by the Peruvian writer, José María Arguedas (1911-1969) in which cultures can co-exist without one subjugating another. As a mixed race American-born mestiza, I’ve long been enamored with the poetry, music, and cuisine of my mother’s beautiful homeland of Perú, and explore these in my compositions, and Cuentos is the newest of these efforts.

GS: The other half of the title of this new piece is “Four New Folk Songs,” which leads me to believe that you don’t quote existing folk songs. Is it more modeling or do you actually reproduce songs?

GLF: No quotes. But there are hallmarks and characteristics of what you might find in folk music. It’s very liberally reinterpreted.

GS: I think I saw in a different interview that you’re “coming out of retirement” to play in this performance, as a pianist?

GLF: [Laughs] Oh my goodness.

G: Can you talk about that a little bit? I know you were nominated for a Grammy as a pianist, so that means you’ve got chops.

GLF: You know, at the time I was nominated, I happened to be playing with great musicians. Really! I was stuck to them. We did the CD, and I played on a couple of pieces, so it wasn’t that I was nominated, I was nominated alongside them.

But it is true. I would say composing is maybe 90% of my life and the other 10% is playing. When I was younger and studying at University of Michigan, and shortly after, I played quite a bit. And I was beginning to get some gigs professionally, and then the composing just took its own trajectory.

I always thought I had more to offer as a composer. You know, the University of Michigan is turning out these pianists that can play new music, as well as Beethoven and Mozart. My Mozart and Beethoven might be interesting to a few. [Laughs] But, although I love listening and have great appreciation for people who play the standard repertoire, my contribution is really in the other less common repertoire that I can play, and I can compose a lot more repertoire than I can play.

GS: How about your relationship with Sphinx. Your received the Sphinx Medal of Excellence in 2013, and in 2014 you were a part of a panel about race and composition with Sphinx founder Aaron Dworkin and others at the Sphinx Con, an annual conference focusing on ethnic and racial as well stylistic diversity in classical music. How long have you known about the Sphinx Organization and how long have you been working together?

GLF: I knew the founders before they founded Sphinx when we were students at the University of Michigan together. I saw the beginnings of these ideas, what it means to have some sort of diverse background going into classical music. For Aaron Dworkin that came in the form of expanding his string playing to education and and advocacy. So that’s when he founded the Sphinx Organization.

The award was an incredible honor, and the UMS performance will be the first time I work with the organization creatively, a full concert with rehearsing, creating a body of work, and so forth.

GS: I’ve known you for a long time, and I think it’s not just your heritage and how it comes across in your music that sets you apart, but also in the other things that you do as a composer. Your participating in panels and demonstrations, for example. Some composers feel they should only express themselves and their music, not necessarily give presentations or do that sort of work that I think you do very well. Where does that come from? What drives you to be a communicator for diversity as well as a composer?

GLF: Well, you know, everyone is more or less comfortable with public speaking. I didn’t plan on that, it was an accident. I happened to discover other ways in which I could enjoy music with people. For example, just talking about it. I think I discovered this in grad school, so it was rather a late discovery.

I also always wanted to make sure that this doesn’t come at the expense of the music itself, too. There are musicians who consider themselves advocates more than players or artists. And that’s great. I’m inclined to first make sure that I’m the best composer I can possibly be. I think I’ll provide more benefit to the music community if I keep my head on straight.

But engagement of this type enhances what we composers can offer. I’m very happy when I see the next generation be so proactive, in terms of making even more connections beyond the stage. I don’t know, it might be a little bit of my Berkeley hippie upbringing. [Laughs]

GS: Let’s talk about your connection to Southeast Michigan. You went to Michigan for your doctorate, but now you’re the composer-in-residence with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. What do you feel your connection to the area is, and how has it changed since you’ve re-rooted here?

GLF: That’s a great question. I think you touched on it. There is a difference from when I was in school. I think it’s safe to say that a lot of students in Ann Arbor don’t necessarily get to know Detroit. It’s a drive, so there can be transportation reasons. Most people don’t go there to hang out; they go for an event. You get in and get out. I went to a few DSO concerts when I was at Michigan for my doctorate. And that was about it.

In the years that have passed since I graduated, I have also been composing for other orchestras. It’s amazing when you get to a city and you start to get to know the place and the people. Your world gets larger, and you start composing music. You talk to civilians. You know, people who are not musicians. [Laughs]

When the DSO came to me, I thought, now it’s my turn to be in one of our great cities that’s fallen on hard times. Maybe also with my connection to the area and Ann Arbor, in some sense I wanted to rectify how I had neglected Detroit in the past. What I’ve learned as the composer in residence with different orchestras now is a sense of humility. I’m not going to be able to change a lot of things, but I can give what I can give.

It has been amazing to witness how Detroit is changing. Every time I go back I see another part of the city that has developed. A community garden has sprung up. Or, a building has been bought and is being renovated. The changes are tremendous. Artists are coming in. Musicians, writers, visual artists are buying warehouses and setting up. Being there when the new mayor was voted in, seeing long lines of people getting ready to vote, when sometimes people don’t vote across the country. The sense of community is incredible.

GS: I have one more question. I can’t help myself because I’m doing this for UMS. I’m curious; did you go to a lot of UMS concerts when you were a student here? And is this your first time having your music as part of a UMS performance?

GLF: Not the first time for my music, but I wasn’t at the concerts when my music was performed at UMS before. So, from my perspective, this will feel like the first time.

But, yes, I did all the student rush things every year when I was a student. We’d stand in a long line. [Laughs]

GS: Oh yeah! That’s how I saw Einstein on the Beach.

GLF: I remember one time, the very first year I was a student, we stood in the rain for hours, oh man. I can’t wait to come back! UMS was one of the earliest supporters of Sphinx. Sphinx has its roots here in the Ann Arbor and Detroit area, so the Sphinx concert is going to be a very special one.

Interested in more? Explore the archive of Garrett’s interviews with UMS visiting artists.

Garrett Schumann: Embracing the New

Editor’s Note: Garrett Schumann is a regular contributor to UMS Lobby.

Photo: A tandem bicycle.

My summer has been full of new experiences. By the second week of June, I was newly married, a recently minted Doctor of Musical Arts, and — only in the most nominal sense — had become an internationally recognized scholar of heavy metal music.

Over the subsequent months, I visited several new places, my wife, Shana, and I rode a tandem bicycle (and, yes, we are still married), and, while in Helsinki, Finland, I drank a licorice-and-sea-salt liqueur for the first — and, likely, last — time. These experiences, and the rest of the season’s discoveries and upheavals, have been spontaneous and inevitable, challenging and euphoric. I have found it hard not to celebrate everything I’ve done this summer, happy or otherwise, because my life has changed irreversibly. I will never again be a student, for example, which has been my primary occupation for over twenty years, and now, with Shana at my side, my life, and the way I make life decisions is, wondrously and beautifully different.

Weddings and transformation

We had a Jewish wedding ceremony, so we broke glass to punctuate our entry into the world as a newly married couple. My family is not Jewish, so, in the weeks leading up our wedding day, I looked into the meaning of the glassbreaking so that I would better understand it, and be better equipped to explain this ritual to my friends and family. One interpretation I was familiar with is that the broken glass serves to remind the couple, and everyone at the wedding, that life is full of happiness and sadness, good things and bad. A different reading of the glass’s symbolism, which my mother-in-law directed me to, is that breaking the glass represents the fundamental transformation the couple’s experience; the glass is irreparably altered, changed from a solid, singular object into a collection of many pieces. The wedding also transfigures the couple: our lives are no longer wholly individual, but united by love and commitment.

To be strictly literal, breaking the glass represents the opposite effect of getting married – unlike the light bulbs we stepped on, marriage has not shattered my wife or me, but has made us stronger and more connected. Nonetheless, I am fond of what the ritual symbolizes.

Music is like weddings…

Our stepping on the glass signaled simultaneously the end of one interval in our lives and the onset of a new period, marked by the unknown promise of the future together. I suppose many points in life can be described in these, or similar, terms. We happen upon countless events whose endings dually serve as closure for what has passed and the initiation of something new. According to Christopher Hasty, a music theorist based at Harvard, we also perceive music, and musical time, in this way. In the most abstract sense, he argues we can only understand a sound’s duration once it has ended, and such endings also operate as the beginnings new, indeterminate, sonic durations.

Practically, however, Hasty notes the characteristics of past musical events impact how we interpret the present. In a way, we are biased towards the hope that what is newly becoming in a piece of music will reproduce elements of what has already come to pass.

And then there’s heavy metal…

I discovered Hasty’s theories on musical time while researching a new paper on meter in heavy metal music I will present at the Ann Arbor Symposium IV, a popular music conference organized by the University of Michigan School of Music, Theatre, and Dance.

Surprisingly, I find his philosophy is applicable to the new period in my professional and artistic life. Now that I am out of school, I face the new challenge of structuring my time so that I can fulfill the potential of my scholarly work and my ever-present drive to compose new music. Outside of the University of Michigan’s institutional framework, I must pursue and secure new opportunities for myself as a composer, researcher, teacher, and so forth. So far, I have succeeded in each of these arenas. I am presenting at the aforementioned Ann Arbor Symposium, I secured a performance of my song-cycle Bound at New Music Detroit’s Strange and Beautiful Music marathon concert in September, and I will continue to teach aural theory for the University of Michigan’s Musical Theatre department this coming school year, as a lecturer. However, each of these opportunities will eventually terminate, and, like with a musical event, that conclusion will mark the beginning of a new, indeterminate, period of finding out what will happen next.

New kinds of freedom

As daunted as I may be by this projected future, I find it exciting to embrace the new. The last nine years of my life — from the day I matriculated into my undergraduate degree on the quad of Rice University, to May 1, 2015, when I was hooded as a new Doctor of Musical Arts on the stage at Hill Auditorium — have been dominated by classes, exams, and lessons. The constant newness of my present may be riddled with uncertainties, but it is also replete with freedoms. I may be in an uncharted professional/artistic place, but being in Ann Arbor, teaching at the University, working with UMS, and having my wife and friends whom I have known for years in my life means I am also surround by enormously supportive continuities. The future is, perhaps, not too different from the life I have known; and, newness, after all, is just a natural byproduct of time’s passage. To paraphrase the final pages of Thomas Mann’s novel The Magic Mountain: time, we say, will go on, in its furtive, unobservable, competent way, bringing about changes.

You can too: Just listen to new music

The excitement of embracing the new I find myself immersed in is, of course, available to all of you without needing to undergo major life changes. Just listen to new music. As the philosopher Suzanne Langer wrote, “music makes time audible.” So, when we listen to music we do not know, we experience the newness of the future just like we do in life. On the other hand, you can escape the perception of time’s newness – to an extent – by listening to music you know well, as a familiar piece of music can be uncannily predictable.

If you find yourself intrigued by this notion, test it out during UMS’s upcoming season. Look at UMS’s concert schedule and select something new and something you know. During the performances, consider how your experience of time changes because of the music; and, once you have attended both, think about how this perception differed between the two events. This experiment will work best if you choose to compare listening experiences that are as different as possible. So, if you have a history of subscribing to the Choral Union Series, plan to hear Pinchas Zukerman play Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D major on January 11, but first attend the renowned Japanese Butoh dance group Sankai Juku’s performance on October 23. Likewise, if you love the contemporary offerings of UMS’s Jazz series, circle The Bad Plus’s concert with Joshua Redman on April 23 in your calendar, but also plan to hear the world-class early music ensemble Apollo’s Fire perform Bach’s St. John’s Passion on March 15.

Music makes time audible

Paying attention to how we experience time through music is just one of the wonderful ways we can learn about life by engaging with art. I believe that music, more than any other artistic discipline, provides us with a conduit to connect with the furtive flow of time that ensures every experience we have is new, if only temporally. I believe listening to unfamiliar music exposes us to perceptual obstacles analogous to the challenges inherent to the constant newness of life’s unfolding. A new piece of music can be a self-contained simulation for facing unexpected moments in time; and, though we cannot be fully prepared for what the future will bring us, it is interesting to consider our experiences listening to music as practice for life’s inevitable uncertainties.

Music can teach us that an indeterminate future can be equally as beautiful as it can be intimidating, that the unknown is also full of splendor. There is something ineffably glorious and stunning about the moments when a piece of music surprises you in a manner that seems inevitable. A related serendipity occurred at our wedding, when my wife’s procession to the chuppah lined up with the accompanying music exactly as I had dreamt it would. I was overwhelmed by incredulity and assurance, a calm wonder that, with my wife, any changes the passing of time may bring will now be so much more beautiful to experience. Three months later, I recognize I am excited for my life’s newness thanks to moments like this, the continuity of my family and community, and the way my years of listening to music – unfamiliar and otherwise – has helped me practice embracing the new with vigor and optimism.

Do you often listen to unfamiliar music? Do you notice a difference in your experience of listening to the new and familiar?

Perspectives on Melody in Dvorak, Tchaikovsky, and Vasks

Artemis Quartet perform in Ann Arbor on April 19, 2015. Photo by Molina Visuals.

The Artemis Quartet’s program features two stalwarts of their usual repertoire alongside a recent work by one of Europe’s leading contemporary string composers, Peteris Vasks. Born, educated, and based in Latvia, Vasks began his musical life as a bassist before transitioning to composition in the 1970s. His experiences as a string player are likely responsible for the plentitude of pieces for string ensembles among his output. More importantly, his familiarity with the sound of string instruments equips him well to write highly evocative, highly expressive string music.

A strong melodic focus

While it may seem that Vasks, Dvořák, Tchaikovsky have little in common beyond the fact they are all European composers, this is not wholly the case. All three create music with a strong melodic focus that gravitates toward a clear lyrical style. Of course, Vasks enjoys and employs more freedom than Dvořák or Tchaikovsky, whose aesthetic choices were effectively dictated by a syntax of musical ideas shared among essentially all contemporaneous European composers. Indeed, melody is a de rigeur element of nineteenth century music, and Tchaikovsky is regarded as one of the best melodists in history. The Quartet No. 1 in D major (1871), part of the Artemis Quartet’s April 2015 program, certainly lives up to his reputation, although its tunes may not be as famous as those featured in Tchaikovsky’s ballets.

More interesting are the melodic experiments present in Dvořák’s Quartet in F Major, “American” (1893), which contains the pentatonic scale in abundance. The presence of this five-note scale, which also appears prominently in Dvořák’s Symphony No. 9, “From The New World” (1895), may have garnered the quartet’s nickname, as the pentatonic melodies suggest non-white American folk music. Dvořák wrote fondly of African-American music, which he heard while living in the United States, and it’s reasonable that he may have tried to refer to this tradition in the pieces he composed during this period.

Thinking beyond the movement

Although Vasks values melody in a very traditional sense, he treats it more dynamically than Dvořák or Tchaikovsky. As you will hear, Vasks thinks beyond the movement of one note to another; he develops color, register, and texture as well. Vasks’ string orchestra work Musica Dolorosa (1983) demonstrates this quality very clearly, moving from a mournful, romantic melody to an intense, aleatoric swarm of dissonance. Although there is no existing recording of Vasks’ String Quartet No. 5 (2008), his other quartets possess these same characteristics, despite the more limited instrumentation. Thus, it seems fair to expect the same in his more recent work.

In program notes written for his publisher, Vasks describes elements of his dramatic String Quartet No. 5 as, “atmospheric”, “a cry of utter desperation”, and, “a forgiving, loving look at a world tortured by grief and contradictions.” Structurally speaking, this quartet marks a departure for Vasks. String Quartet No. 5 has only two movements – being present and so far…yet so near – while the previous four all have at least three, with his String Quartet No. 4 (199) sporting five wildly contrasting movements. It will be interesting to see whether the seemingly condensed form of the String Quartet No. 5 manifests a unified and cohesive piece, or if the two titled movements simply represent two adjacent, yet individual, regions of diverse, free, and expressive musical ideas.

Interested in more? Explore our listening guide to the evolution of the string quartet.

Artist Interview: Jennifer Koh, violinist

Insightful and passionate violinist Jennifer Koh talks with UMS Lobby contributor and composer Garrett Schumann about creative programming choices, contemporary works, and the power of music.

The virtuoso violinist returns to Ann Arbor (following her 2012 appearance in the Philip Glass and Robert Wilson opera Einstein on the Beach) with the third and final part of her Bach and Beyond series on Friday, February 6, 2015.

Garrett Schumann: Throughout your career you’ve maintained a consistent interest in programming contemporary and often newly-commissioned works alongside standard pieces in the violin repertory. Where did this passion for combining tried-and-true pieces with new pieces come from in your development as a violinist?

Jennifer Koh: I think it was always just curiosity. When you first make your foray into discovering classical music, it’s really new to you. Now, to me, it doesn’t really matter what time period the music comes from, whether it is “new” or “old.” The one thing that has been such a great pleasure about working with contemporary music is that I can actually get to meet and work with living composers, and that has been a really wonderful, beautiful part of doing the work.

GS: Do you think that putting older pieces next to contemporary work brings new things out of them?

JK: Everything is in context. We live in a certain age, and every day that passes takes us one day further away from the society of Bach, for example. I actually remember hearing a program by Peter Serkin. This program was a little unusual for him; he was doing all the Bach concerti, and what was fascinating was that everything sounded so modern. I realized that art is about re-discovering.

When I first created the Bach and Beyond program, I bookended the program with Bach because I wanted to create a journey through history and into our contemporary landscape and then return to Bach. You create this circular journey, and you realize that the experience of listening to the things in the middle changes how you hear Bach. And, in a way, it also changes how you frame each of the composers.

I feel that contemporary music links us to the past because it does have this history. Most composers work within the richness of that tradition, but they also add their personal viewpoint to it. The great thing about art, and the great pleasure for me personally as a musician, is that it has the ability to change the world. It creates a situation where people can have a space to be very present, but also go to places that they normally don’t want to go to and access those emotions that they don’t necessarily experience every day.

GS: Speaking of this sort of cyclical nature of Bach and Beyond, what’s really interesting about your performance this season is that when you did your first UMS performance in 2010, you were at the beginning of the Bach and Beyond series. Now that it’s coming to a close, how does that feel?

JK: It’s been an interesting process. I actually remember the very beginning, when it was still very difficult to convince people to do this solo violin program. And I remember when I first came up with the idea, a lot of people said, “Nobody’s going to want to book that.” Nobody does solo violin programs. But now, Bach and Beyond has become much more accepted, so one of the beautiful things for me has been that people have begun to see violin as an instrument that has enough timbre to hold an entire program.

I was also at UMS with Einstein on the Beach, and that experience opened my world in a wonderful way. Those performances were the first preview performances of Einstein, and the first extensive rehearsal process was there. It feels like UMS has been a starting point, and so it’s nice for me to return.

GS: What was the experience of working with director Robert Wilson during Einstein on the Beach like for you?

JK: It was really organic in the sense that it’s always been interesting for me to work with artists that I really admire and respect. When I first met [Robert Wilson], I was intimidated. But then, when I saw how he worked, I felt an immediate connection. I respected his working style because he is a perfectionist, and that’s something that I do myself.

When I got the call for Einstein, I knew immediately that I wanted to be a part of it. But I was actually terrified because I don’t have any acting background. But things that terrify me, I find the most interesting. For example, doing Bach and Beyond when I first thought of it was terrifying as well.

What I hope in the end for any piece, whether it’s Einstein or Bach and Beyond, is that people who actually hear the piece trust you. And that they’ll go along on the journey.

GS: Now that Bach and Beyond is wrapping up, what do you have set up for the future?

JK: My next purely performance-based project is called Bridge to Beethoven. That is really an exploration of all ten Beethoven sonatas, but will also have four new works in conversation with it.

When I first came up with the idea, I had just seen a production of Julius Ceasar by the Royal Shakespeare Company. They had made Julius Ceasar a despotic military junta leader in Africa. Again, that inspired me to think about how changing the setting can really alter our assumptions.

So when I was exploring the Beethoven sonatas, I wanted to approach the assumptions that we have in our current psychology. For a lot of people, Beethoven is the “definition” of classical music. If you say “Beethoven,” people tend to have a very specific perception of the music. The question for me, became, “How has classical music evolved?” If you look at his music, he was quite a revolutionary, but now oftentimes it’s performed such that it doesn’t sound new, it doesn’t sound modern. For me, what was important was to bring out these parts of the music that are not just “elevator music.” To really hear those revolutionary aspects in his compositional process.

What’s also interesting to me and helped to inspire this project is that I come from a non-musical background, but at one point, I discovered music is something that I love. Many American composers also come from non-musical families, so what is it about music that draws us to that platform? I wanted to create that kind of dialogue in a compositional way.

My ethnic roots are also in a country halfway across the world in Asia. How is it that I came across classical music? How is it that this art form has changed my life to the degree that I can’t imagine my life without music? Questions like this are reflected in the project as well.

Anyhow, we’re actually starting it late next season and we start it in California, then we take it to Virginia, and then it will go to New York.

GS: Well, I have to say that as a young idealistic grad student, I really appreciate the consideration you put into the program and the fact that you want to address issues that are larger than the music or parts of the music, these are things that are sometimes missed in the traditional setting.

JK: I agree. There is this idea of reaching outside of what you already know, and it’s becoming less and less common. I think that the arts are great because they are an open experience that’s about empathy, about having an experience that you don’t have on a normal basis.

Interested in learning more? Check out other interviews by Garrett Schumann.

Artist Interview: Flutist Tim Munro, eighth blackbird

Eighth blackbird. Photo By Luke Ratray.

The Chicago-based ensemble eighth blackbird combines the finesse of a string quartet, the energy of a rock band, and the audacity of a storefront theater company in a dazzling performance coming to Ann Arbor’s Rackham Auditorium Saturday, January 17, 2015.

Composer and UMS Lobby contributor Garrett Schumann chatted with eighth blackbird flutist Tim Munro about the group’s unique instrumentation, theatrical flair, and magical moments onstage.

Garrett Schumann: What is eighth blackbird?

Tim Munro: Well, eighth blackbird is a chamber music ensemble specializing in music by living composers. One week we might play music that’s influenced by indie rock, the next music influenced by Balinese Gamelan, the next by an abstract piece of modern visual art.

We often memorize the music that we play, which allows us to take away stands and to have a greater intensity of communication on stage and with the audience. Sometimes that means we actually move around the stage to make manifest some of the relationships that are already inherent in the music. So a lot of the time we are trying to make this new composed music more immediately vibrant and engaging for audiences.

GS: Terrific. When you created the group in 1996 there had been ensembles with the same instrumentation as eighth blackbird for a few decades. How consciously did you guys see yourselves as emerging from that kind of ensemble tradition?

TM: To speak about the instrumentation first, eighth blackbird was sort of a put-together group. At the Oberlin conservatory, this conductor, Jim Weiss, put the group together to play more challenging repertoire, stuff that isn’t normally covered in the run of conservatory conductor. And this instrumentation seemed like the perfect kaleidoscope in everything. You have strings, you have winds, you have piano, you have percussion. You’re able to sound like you’re a string quartet, you’re able to sound like you’re a piano trio, you’re able to sound like a percussion ensemble, you’re able to sound like a full orchestra and there is just every combination possible in this instrumentation. This, I think, is why in the 20th century, it really exploded.

I think the biggest influence on eighth blackbird is an ensemble with a different instrumentation, which is the Kronos Quartet. It plays a hugely diverse range of material. Everything from the wildest, most experimental modernism to the kind of obvious, fun-loving minimalist to collaborations with popular artists and world music– and doing it in a way that made it visually engaging to audiences, but was casual enough that people could feel relaxed. So I think that was the biggest influence on eighth blackbird in its earliest stages.

GS: How do you come with this diversity of programming? What do you think it is about eighth blackbird that does that diversity so well?

TM: I think that’s something that we try very hard to represent in our programs not just because we want to check all the boxes, but because we want people to never feel bored, but to always have people engaged in a concert. The diversity of the programming just reflects the diversity of different proclivities within the ensemble. Each performer in eighth blackbird is part of the artistic direction of the collective. We are all music directors of eighth blackbird and we are all coming from very different places. We all have different music that we love and I think our programs are reflective of the enthusiasm of the group all together.

What unites all of the music that we play is something in it that is unique: a color that we haven’t heard, a particular approach to constructing a piece that we haven’t done before, a spark that inspires the piece that we haven’t encountered before… something that we can then play with theatrically. So each piece on the program in some way captures something that is unique even if they are in totally different worlds. Everything on the program gives us a little something atypical or strange.

GS: Composer and Northwestern professor Lee Hyla passed away suddenly in June 2014. What was your group’s relationship with Lee Hyla and his piece “Wave”?

TM: Well, it was such a shock for everyone in the ensemble and for the whole music community in Chicago because he was such a huge presence. He’s an original. His music has a rawness and an unvarnished-ness that feels so appropriate and typical of someone of that sort of American maverick tradition. Every member of the group has a particular fondness for one of Lee’s pieces and we all loved his music. We don’t know him well personally, I don’t think anyone in the group knew him terribly well, but we are all such huge fans and were all so excited to be able to commission the piece.

I can tell you that already in rehearsing this we’ve discussed how the piece is put together. It’s a lot of fragments, it’s a piece that’s shards of things. Beautiful, pummeling, fractal, little elements that are all in shards, sort of constructed. And when we come to the moment of rehearsal where we don’t quite know our way forward, that’s often when we will talk directly with the composer. And so whenever that happens, we have that voice in the room, but we won’t be able to do that. So I’m not sure how it will affect our performance. It’s too soon for us to say.

Maybe because this is the only piece of his that we’ll ever be performing posthumously, there may be something different about the way that we and future groups approach it. It’s a piece that’s actually in its kaleidoscopic-ness begins with this vast, incredibly slow, incredibly astute music, and the last voice is the cello who has this upward gesture that almost feels like a question mark. I don’t know if one should put any emphasis on that, but for us, this performance asks us to think about those things.

Interested in learning more? Check out other interviews by Garrett Schumann.

Prokofiev, Shostakovich, and the Year 1936

Pianist Behzod Abduraimov, who’ll perform with the Mariinsky Orchestra on January 24, 2015. The program features works by Prokofiev and Shostakovich. Photo by Ben Ealovega.

1936 was a portentous and dramatic year in the lives of Sergei Prokofiev and Dimitri Shostakovich. That summer, Prokofiev would move his family and career from Paris back to the Soviet Union under the impression that he would be able to compose relatively freely and continue touring abroad. However, when Prokofiev arrived in Moscow, his passport was confiscated. He was trapped. Meanwhile, in January of 1936, Shostakovich became a target of state-guided criticism and censorship. After rising to stardom in 1935, Shostakovich’s future as a composer was suddenly in jeopardy.

Prokofiev and Russia’s greatest expatriate composer

Prokofiev’s 1921 Piano Concerto No. 3, to be performed by the Mariinsky Orchestra on January 24, 2015 at Hill Auditorium, in many ways, symbolizes the brilliant career that he unwittingly relinquished when he returned home in 1936. Premiered by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra three years after Prokofiev’s original emigration from Russia, the work did not garner much attention for another year, when renowned conductor Serge Koussevitsky presented the piece in Paris. Prokofiev even performed alongside the London Symphony Orchestra when the concerto was first recorded in 1932.

The Piano Concerto No. 3 remains one of Prokofiev’s most popular works, and represents the composer’s appropriation and manipulation of Romantic styles and forms. Typical of Prokofiev’s piano music, the soloist’s part is impressively virtuosic and bumptious, particularly during the concerto’s rousing finale. The work’s three movements follow a traditional slow-fast-slow scheme, but its overall content is slightly more dissonant than Prokofiev’s later works, as he did not start to seek a simpler style until the mid-1930s.

Excerpt from Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 3 performed by Mariinsky Orchestra. Courtesy of Mariinsky Label. Catalog also available via iTunes.

Although Prokofiev was already well known in the West in 1921, the Piano Concerto no. 3 certainly contributed to the international success he enjoyed from 1918-1936. When Prokofiev returned to Moscow, he did so believing his career would continue as it had. Exactly why Prokofiev left Paris is unknown, but one theory involves Shostakovich’s fall from grace. Despite Prokofiev’s fame in Europe and America, he had to compete with Rachmaninov and Stravinsky for the title of Russia’s greatest expatriate composer. Seeing that Shostakovich’s career might be over, Prokofiev may have thought he could return to Russia without a rival, and enjoy the national celebrity all to himself.

“At the same time Prokofiev returned to Russia a hero, Shostakovich’s career began to fall apart.”

Shostakovich’s challenges began less than a month into 1936, when, on January 28, the newspaper Pravda published a state-directed condemnation of his hugely successfully opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District entitled “Chaos Instead of Music.” The work had received 177 performances in Moscow and Leningrad in two years, but was suddenly derided by the mouthpiece of the Soviet state. Two similar articles hit newsstands in the following months, each criticizing Shostakovich’s music on the grounds that it violated Stalin’s cultural paradigm of “social realism.” At the same time Prokofiev returned to Russia a hero, Shostakovich’s career began to fall apart.

Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 4 immediately suffered from this new government criticism. Coming off the high of Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, Shostakovich was halfway finished with the work when “Chaos Instead of Music” was published. Given Shostakovich’s new public circumstances, his friends and colleagues urged him to placate Pravda with the new symphony, which Shostakovich refused to do. He arranged a premiere performance with the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra for December 1936, but it was cancelled under ambiguous circumstances. The Symphony No. 4 did not receive it first performance until 1961, when the Soviet cultural ministry finally relaxed its expectations for Shostakovich and other Russian artists.

Excerpt from Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 4 performed by Mariinsky Orchestra. Courtesy of Mariinsky Label. Catalog also available via iTunes.

Unlike Shostakovich’s previous two symphonies, Symphony No. 4 (which is also part of the Mariinsky Orchestra’s program this January), does not feature vocalists, but rather relies on a large orchestra. It is an enormous, hour-long work that is filled with subtle suggestions of Mahler, whose music Shostakovich studied enthusiastically. The symphony’s form is unusual in its three movements of drastically imbalanced lengths. Almost bizarrely, the symphony’s outer movements are both over twenty minutes long and the inner movement lasts less than ten. However, in listening, the piece seems fairly continuous, and exhibits embryonic forms of the distinct musical characteristics Shostakovich would develop over the rest of his career.

Although Shostakovich’s Fourth Symphony was buried by the controversies of 1936, he rebounded quickly. The next year, Shostakovich premiered his landmark Symphony No. 5, which redeemed himself both with audiences and Soviet leadership. At the same time, Prokofiev was struggling with the unexpected realities of his new life in Russia. Not only was his passport terminated upon his return to the country, but he met much more resistance from the cultural ministry than he had anticipated.

For the remainder of Prokofiev and Shostakovich’s time as contemporaries, their careers were very much alike. Despite their differences, Prokofiev and Shostakovich shared in the classic dilemma of Soviet-era composers: the struggle to simultaneously satisfy one’s artistic desires and the desires of state.

Interested in learning more? Explore the Mariinsky Orchestra’s history in Ann Arbor through our archives.

Artist Interview: Cellist Paul Watkins, Emerson String Quartet

Photo: Emerson String Quartet. Photo by Lisa Marie Mazzucco.

The Emerson String Quartet returns to Ann Arbor on October 5, 2017 to perform with Calidore String Quartet.

Cellist Paul Watkins joined the quartet in May 2013. UMS Lobby contributor and composer Garrett Schumann chatted with Paul about what it’s like to join the quartet, his British sense of humor, and his role as artistic director at the Great Lakes Chamber Music Festival.

Garrett: You joined Emerson Quartet during the 2013-2014 season. We often hear about the demands of precision and cohesion that string quartets require. What has the process of assimilating you, a new voice, into the Emerson Quartet been like?

Paul: Well, you know, it has its challenges because I’m coming into a group of guys that’s worked together for the last 37 years. And in fact, in the case of Phil [Setzer, violin] and Gene [Drucker, violin], they’ve known each other and each other’s playing since they were college students, going back more than forty years. There’s a degree of responsiveness that they have to each other which I have to catch up with. But luckily when we played together for the first time, I think we all felt a very natural and quick connection in our styles of playing. Good basics to work from. But we’ve had to rehearse a lot over the last year, probably more than the quartet was used to.

Garrett: I saw that the press release announcing your joining the group noted your vibrant sense of humor.

Paul: Ah! Did it! Good.

Garrett: I’m wondering what you have to say about that. Do you think that part of your personality had any specific implications in your first season with the group, or is there any particularly funny anecdote from your first season that would match the expectations that were built by that press release?

Paul: [Laughs] That’s very interesting. I think all three of the guys in the quartet apart from myself have got very highly developed senses of humor. So you know, we fool around in rehearsals. Maybe the subject of a lot of our jokes in our first year has been the difference between British English and American English. One thing that comes to mind, too, is just before I gave my first official concert with the quartet, they gave me a little spoof “welcome” pack, which had various characteristics of the individuals in the quartet, slightly exaggerated. It’s been quite funny for me to discover that pretty much all of the things that were there are absolutely true. [Laughs]

Behind the scenes with Emerson String Quartet:

Garrett: [Laughs] So, the program that you’ll be performing at UMS has Beethoven and Shostakovich and also has the new piece by Liebermann that was a UMS co-commission. Could you talk about the process of creating a program with the quartet? What are the things that you discussed and thought about when you designed it?

Paul: I think for a lot of quartets that have been together for a long time, each individual member of the quartet tends to have a different role. And in our quartet, Philip has a lot of responsibility for programming, it’s something that he loves doing. He really relishes the prospect of putting together different pieces and relating composers to each other within a program or within a concert series. While he does the lion’s share of that work, we other three have a lot of input as far as that’s concerned.

Since I joined the quartet, I’ve also shared the repertoire that I’m particularly interested in. For me, Beethoven string quartets are still really the towering achievement in string quartet literature. Nothing’s equaled or surpassed them since he wrote them. My top priority personally was to explore as many Beethoven string quartets as soon as possible with the Emerson.

Garrett: How do you think Ann Arbor audiences will feel about this program with its mixture of very traditional Beethoven and Shostakovich and also this new piece, which none of us will have heard of course?

Paul: Exactly. We haven’t heard it yet! It’s nearly ready. As with a lot of composers, they write very close to deadline, but we’re expecting it to arrive really any day now, so that we could start working on it over the summer. Lowell Liebermann is a very lyrical composer…I’m not sure! I’m nervous to commit to anything in particular about the piece because I’m not sure what kind of piece he is going to write! In a way that’s a kind of surprise.

Garrett: I’m a composer myself so I understand your hesitance to commit anything because who knows! Well, your other big news in addition to the Emerson String Quartet is your new position with the Great Lakes Chamber Music Festival.

Paul: Indeed! I’m very excited about that.

Garrett: What attracted you to that position?

Paul: Actually, in a couple of hours, I’ll go to Detroit because it’ll be the opening of the 2014 festival. The Great Lakes Festival has a very strong personal connection for me because Detroit is the home town of my late mother-in-law Ruth Laredo, who was a very distinguished American pianist and a wonderful lady and a powerful influence on me and many other people.

Her sister still lives there, so they’re a great family connection. She was also a great friend and artistic companion to James Tocco when he founded the festival twenty years ago with his brother.

There’s also a wonderful team of people working for that festival, and it seems that it has a very unique and welcoming atmosphere. This all made me think that working for the festival would be a great challenge but also a great sort of privilege. It’s the first time that I’ve been an artistic director of a major chamber music festival, so I’m very excited to see that work put into practice.

Garrett: What are you thinking about programming, what’s coming up for the festival now that you’re starting your position in August?

As far as programming is concerned, I think what James Tocco has done over the last twenty is very, very good. I want to take that all and develop it. Because I have a British and European background, I want to encourage much more collaboration and cross-pollination between American and European artists. In 2015, we’re going to call it “Coming to America,” which is essentially a kind of short hand for my personal experience of moving to America as a European musician, but also for American composers who have been influenced by Europe, and vice versa.

The opening concerts of the 2015 festival are also going to feature the Emerson String Quartet. That’s an opportunity for me to bring my new friends at the quartet to meet my new friends in Detroit and get things off to a really exciting start.

Garrett: That sounds wonderful. Michigan has a lot of great musicians, composers, and a lot of excited people to hear it. We can’t wait to experience the festival next year.

The Emerson String Quartet performs in Ann Arbor on October 5, 2017.

Updated 7/10/17

The Audio-Biography Of The String Quartet

Photo: Elias String Quartet. Photo by Benjamin Ealovega.

The program the Elias String Quartet will share in its UMS debut on March 18 is like a sonic timeline of Classical Music’s most important genres, the string quartet. The three works the group will perform – Beethoven’s String Quartet in E minor, op. 59, no. 2., Debussy’s String Quartet, and György Kurtág’s Officium Breve – fit together like a veritable textbook on how the string quartet was established, codified, and subsequently transformed from the nineteenth century through the 1980s. It is extremely unusual, and very exciting, to have so succinct and comprehensive a portrayal of music history available on a single concert program.

Of course, this history begins with Beethoven, whose “middle” period works, such as the op. 59 quartets, represent his great turning point from an extremely skilled and gifted Classical composer, to the daring and freely minded Romantic hero music lovers glorify today. Beethoven’s metamorphosis was extremely precipitous to the history of Classical Music in the nineteenth century, and the String Quartet in E Minor, op. 59, no. 2 is certainly part of this legacy. This specific work contains numerous instances of Beethoven’s personality infecting the music’s form and affect; for example, in a likely allusion to the impolite Russian count who commissioned the set this quartet is part of, the work’s scherzo movement features an indelicately harmonized melody that was popular in Russia.

In light of the nearly invincible grip Beethoven’s influence had on nineteenth century composers, it is reasonable to think Debussy considered the German’s quartets when he penned his own in 1893. With that said, Debussy’s String Quartet, like his other music, breaks Beethoven’s mold in a number of ways, most obviously in its exploitation of instrumental color (listen for the prominent pizzicato passages in the second movement!). However, we should not interpret Debussy’s innovations as dismissive – rather, he makes vital changes to a genre that was over a century old at the time, and the musical expressions he explores are echoed by other composers in the early twentieth century, such as Maurice Ravel and Leoš Janáček, among others.

If Debussy’s String Quartet upholds through modification the traditional character of the string quartet as a stand-alone art form, a work like Kurtág’s Officium Breve shows how composers at the end of the twentieth century sought to more totally liberate this ensemble from its longstanding heritage. Officium Breve is starkly different from the other two works on the program – it is made up of fifteen short movements and is populated by constantly-shifting sounds and textures that represent extremely terse expressions on the part of the composer. Ranging from violent explosions of sound to tender periods of quietude, this work is enormously vibrant and deeply captivating.

Despite the fact Officium Breve bears little salient resemblance to the heart of its genre’s tradition, Kurtág’s work echoes the philosophy conveyed in the quartets of Beethoven and Debussy: existing forms may, and should, be altered in the name of artistic expression and ego. Placing living composers in a linear context with widely performed and recognized historical composers helps us, as listeners, observe how recently written music relates to the traditions with which we are more familiar. Unlike ensembles that predominantly program music from the nineteenth or eighteenth centuries, the Elias String Quartet is inviting its audience to share in these connections and is giving us a chance to see how a hugely important genre in Classical Music has grown over its centuries-long life.

Interested in more? Read more Garrett Schumann’s writing on UMS Lobby.

A Slice Of Cold War History With Kremerata Baltica

Editor’s note: The program for this performance was altered slightly at the request of the artists. Check out our up-to-date program information.

Photo: Gidon Kremer, violinist and leader of Kremerata Baltica. They’ll perform in Ann Arbor on February 6, 2014. Photo courtesy of ECM.

Wrapped up in the legend of the Cold War is the very real, yet greatly unreported, cultural conflict waged by agencies in the Soviet Union and the West. Composers, along with other artists, were influenced – knowingly and unknowingly – into acting as pawns in the larger struggle, and both sides attempted to steer their culture in opposition to the enemy’s. This process was most apparent in the Soviet Union, where, particularly during Stalin’s reign, composers constantly worked under the fear that their next work may violate the leadership’s agenda and that they would be censored, imprisoned or executed as a result.

The works of Dmitri Shostakovich and Mieczysław Weinberg bear the stamp of this pressure in their typifying traditional sound. Soviet leaders, such as Nikita Khrushchev, despised twelve-tone and serialist styles and expected their nation’s composers to write works that were more accessible to the average citizen. Therefore, you will find, especially in Weinberg’s Concerto For Violin And Strings and Symphony No. 10, a grandeur and expressiveness akin to late-nineteenth century Western European composers, along with a dedication to classical forms. In contrast, Shostakovich’s Anti-Formalist Gallery represents the kind of rebellions Soviet composers would use to resist the cultural ministry. The work mockingly uses excerpts from one of Stalin’s speeches in which he decries against “anti-People composers.” Yet, as boldly as Anti-Formalist Gallery critiques the Soviet regime, the work was still stunted by the regime’s grip on the composer, and the piece was not premiered until well after the composer’s death.

After World War II, government agencies in the West used financial resources to promote artists and composers whose aesthetic values conflicted with the traditionalism of the Soviet cultural agenda. On occasion, this strategy included coercing composers whose established style was more populist, such as Aaron Copland, into adopting elements of twelve-tone composition. Perhaps because he was British and not American, Benjamin Britten, whose Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge is on this concert’s program, avoided this pressure. Well known for his pacifist views, Britten wrote in his own, more traditional vernacular throughout his life, though his later works tend to be more abstract and dissonant.

Britten’s ability to avoid this cultural war play may have influenced younger composers, such as Estonian composer Arvo Pärt. Early on in his career, Pärt wrote extremely dissonant, “Formalist”, music to rebel against Soviet expectations. But, after a time, Pärt changed his style dramatically and began to write in a decidedly simplistic, if not acetic, musical language. The work of Pärt’s on the program, Cantus In The Memory Of Benjamin Britten, suggests the British composer influenced Pärt, if not in terms of aesthetics, then, perhaps, in their shared neutrality towards the cultural conflict that consumed so many other artists during the Cold War.

Weinberg, Britten, Pärt, and Shostakovich are all part of Kremerata Baltica’s program on February 6, 2014 at Hill Auditorium.

Interested in more? Read Shostakovich: A Life Remembered by Elizabeth Wilson, part of our UMS Book Club with Nicola’s Books.

Interview: Garrett Schumann interviews Composer George Crumb

Photo: Kronos Quartet. Photo by Jay Blakesberg.

Known for its renegade spirit, the Kronos Quartet will perform two different programs on January 17 and 18, 2014 in Ann Arbor. The first program will include George Crumb’s epic work Black Angels, a response to the agony of the Vietnam War,

Our regular Lobby contributor Garrett Schumann sat down for an interview with George Crumb. Read on to learn more about the composer’s influences, his life in Ann Arbor as a doctoral student, and the debut performance of Black Angels in Rackham Auditorium.

Garrett Schumann: You describe Black Angels (1970) as a reaction to the Vietnam War, and I’m curious how the meaning of the piece to you has changed or persisted in the 43 years since you wrote it?

George Crumb: Well, Black Angels was played to pieces, as you probably deduced. It’s more than 40 years old now, but I remember that it was a very difficult piece to write. As far as it relates to the Vietnam War, I had to discover that myself because I didn’t set up to write a political piece. I think that the upset in the world found its way into the music, which happens so frequently.

There are many works throughout music history that are reactions to political events, but in this case it kind of crept up on me. At a certain point, I realized that it was becoming a reflection of a lot of the anxiety and uncertainty of those days. It was a pretty bleak period.

And that coincided with all of the protest movements around the country, which kind of led to a whole new kind of America.

GS: In 2008, the New York Times reviewed a Kronos Quartet performance of Black Angels, and commented that the piece inspired David Harrington, the Kronos Quartet violinist, to form the group. I know Kronos Quartet started playing Black Angels very soon after they formed, and they have performed the piece a lot, and will perform it as part of their upcoming performance in Ann Arbor in January. I’m curious what you think their experience with the piece brings to their performance of it.

GC: It’s interesting, the Kronos Quartet quickly became well-known, but I’ve never worked with them. Most quartets would ask me to sit in and listen to their performance. I didn’t sit in on any rehearsals before they began playing it, so what they brought to it was entirely their own. It was interesting to me to see how a group of musicians would face all of the problems in the piece without my intervention.

And by the same token, I was never been in on the recording sessions. There have been quite a number of Black Angels recordings, and I sat in on many of them, but not in this case.

So those are interesting things for me, and another thing is the way they kind of superimpose a theater gesture on top of the score itself. Their interpretation is a little freer than some of the quartets who have done the work. I think the music allows room for varied interpretation, and they bring their own thing to the music.

GS: There’s a lot of imagery built into the way you write music, so do you see a theatrical interpretation as a sort of extension from that visual aspect that’s embedded in your music?

GC: Yes, I think that sort of thing seems a natural way to approach my music. There are no instructions for that in my score of Black Angels, any kind of special theater effect, but I would like to see more of that in music generally. I’ve always felt that traditional music had that curious, almost poetic, thing built into it. And the musicians have to move. In a way, they’re dancing with their instruments. This sort of thing is part of music, so I can understand how performers sometimes might even want to accentuate that side of it.

GS: What was the impulse, early on in your career, or maybe even before you knew you wanted to compose, to manipulate instruments in unusual ways, to create different sounds?

GC: Many composers had a big influence on my music. One was Béla Bartók, I felt the real power of his influence when I, myself, was a graduate student in Ann Arbor. There’s also a little of Messiaen in my music, comes out in the cello solo part of Black Angels. There’s a little Messiaen-ic sound. It’s an unconscious borrowing, but I recognize it was a borrowing later on. It’s there.

GS: What are your recollections of being here [Ann Arbor] as a doctoral student and has your experience here influenced you at all beyond your education?

I enjoyed so much studying with Ross Lee Finney, he was my only teacher during those years. He really insisted on the clarity of notation, and I’ve never had anyone else I’ve worked with who placed as much stress on that aspect. Another good thing about it is that there were so many students in the graduate program; you learn from your classmates just as much as you do from your teachers.

GS: When you wrote Black Angels, you used folk songs, which are heavily loaded as a symbol of American identity. Do you think it’s important for American composers to address those aspects of national identity directly?

GC: Well, I think it’s a strong element in music generally, and an important thing for a composer to have. If you consider a composer like Stravinsky, all the melodic elements are derived from Hungarian folk songs. And it’s hard to think of Brahms and Beethoven without all of the built-in references to German folk songs.

Black Angels quotes other composers, and it has this quasi-antique music. It’s really a pastiche. These materials can be used by composers to add a kind of depth or perspective. It’s like two different worlds coming together.

GS: Is there something you would like people who haven’t heard Black Angels before to take with them into the concert hall?

GC: I don’t think I’m able to really verbalize that very well. And I guess what the composer should say is: Listen with open ears and try to fit it together. There are the qualities of anguish and love, even, pain; it’s a mixture of all the things our world is made of.

GS: Is there anything else you would like to add?

GC: I wanted to be sure to mention the Stanley Quartet, who did the first performance of Black Angels in Ann Arbor. I had just gotten a commission from them to do a quartet, and I said to myself, I want to write a quartet that’s unlike any other quartet. I want to do something a little original. And I didn’t realize it then how far I would push.

I think they must’ve been totally surprised when they got the score. They finished the piece, read it through. I went out to Ann Arbor a couple days early to make some explanation. They had a million questions. There were different ways of playing their instruments, there were unconventional ways they had to produce the sound.

They hadn’t played much contemporary music, so they were willing to do anything I wanted. And I ended up conducting, can you imagine? I felt like a fool conducting a string quartet, but it helped them keep it all together, and they did a marvelous performance.

There was quite an enthusiastic reception. I think they [the audience] were probably at least in their sixties, verging on seventies, so I’m sure that none of them are alive now. But they sure came through for me and they were really willing to exert themselves and put this thing together, which amazed me.

Interested in learning more? Read our interview with Kronos Quartet’s David Harrington, who describes Black Angels as the piece of music that inspired him to start the group.

Goldberg Variations: A Fun Fact

Nowadays, we celebrate the Goldberg Variations for their beauty and economy, the virtuosity the work demands of the performer and transformative journey this music affords the listener. In this, we forget how the Variations was first performed – on a harpsichord. My first composition teacher, Robert Edward Smith, is also a harpsichordist, and his recording of the Goldberg Variations captures the vibrant energy produced by this instrument’s unique expressive palette.

Photo: An Italian harpsichord. (via)

Generalized as a static instrument, the harpsichord on Robert’s recording is different, and possesses multiple registrations, much like stops on an organ. These allowed him to create gentle, muted timbres in the work’s intimate sections and boisterous, multi-layered colors in more energetic and raucous passages. Although we understand the piano to be a more dynamic instrument than the harpsichord, this special recording of the Goldberg Variations demonstrates how well the harpsichord produces different expressive colors, and suggests Bach must have been aware of this capability when writing for the instrument.

Take a listen to another performance of the Variations of the harpsichord:

Pianist András Schiff performs the Goldberg Variations at Hill Auditorium on October 25.

Why Do I Kazoo?

Truly Render – the UMS’s fabulous Press and Marketing Manager, who is responsible for conceiving the UMS Kazoo Orchestra (which I call “UMSKO”) – told me, at our first event this August, she was surprised I agreed to lead this unusual initiative. This comment struck me as both perfectly apt and a little shocking because I feel my new role as director of the UMSKO was simultaneously unforeseeable and inevitable. In other words, while Truly was dead on that I did not expect to receive her email over Memorial Day inviting me to lead a kazoo ensemble, this new endeavor rather closely aligns with many of my values as a musician and artist.

Unforeseeable and inevitable

For quite some time, I’ve been looking for ways to use my musical skills, abstruse as they are commonly manifested, to interact more closely with my local world. Community involvement, in some form, has been an almost constant presence in my life from my childhood through college, but this impulse has struggled to materialize in my life in Ann Arbor. The UMSKO offers me an avenue for me to return to this kind of activity, but unusually so. Compared to the community concerts I organized and children’s music I composed in college, or the service I participated on my way to becoming an Eagle Scout and witnessed in my mother’s work with Habitat for Humanity, this new venture is clearly different.

The word ‘outreach’ is commonly thrown around in the institutional dialect of musicians, music schools, and concert presenters. But, in my experience, is rarely acted upon with much ingenuity. As I see it, in this period of upheaval for the institutions and individuals who create, perform and present Art music in this country, much more attention and innovation has been directed to the quality of the content displayed on the stage than the way the actors behind the content interact with the people sitting in the seats.

UMS has been different, at least as long as I’ve been aware of it. UMSlobby.org, to which I’ve contributed for three years, is a special forum unto itself, and is constantly featuring new pathways for the patrons of UMS to interact with the material UMS presents each season. Last year, UMS, like many similar organizations (though, none so large), experimented with Tweet Seats, which allowed audience members to participate in a unique, extemporaneous conversation alongside a given live performance. Embracing new media like this is obviously important, but these arenas are sometimes limited insofar as they include some barriers to entry and may discourage or disrupt some patrons as much as they galvanize others.

The kazoo, on the other hand, is democratic

The kazoo, on the other hand, is as democratic, populist and universal a device for audience and community engagement as anyone, even the most ardent idealist, could hope for in the sophisticated cultural space UMS occupies. At least, this is my interpretation of the response we have received at our public appearances, and in the conversations I’ve had about this project with friends, family and strangers. Almost to a person, learning about the UMSKO has sparked instantaneously enthusiasm, and why shouldn’t it? Kazoos represent a vehicle for musical performance with virtually infinite accessibility – we have handed out kazoos to over 800 people and none has failed to produce its iconic buzzing tone.

I realized this as I manned the UMSKO’s station at Artscapade this August, where I led a string of demonstrations instructing electrically enthusiastic undergrads how to play part of the theme I’ve composed for the group. In their excited and attentive faces, it occurred to me that we weren’t just giving them something fun to do, or another way to be loud – these kazoos were empowering these students. While the technological initiatives UMS has embarked on fill a quintessential and otherwise inaccessible role in a contemporary audience’s experience of live events, they create a different kind of participatory environment then the UMSKO. Ventures like UMS Lobby and Tweet Seats open new avenues of conversation for concertgoers, and create a more immediate and active responsive zone wherein UMS patrons can connect with one another more seamlessly before, during, and after a performance.

What amazes me about the Kazoo Orchestra is how it enables participants to have a role in the creation of one of UMS’s musical products. In other words, the UMSKO doesn’t just change the way concertgoers interact, it redefines what it means to be a member of UMS’s audience. Of course, I’m basing this all on the Kazoo Orchestra’s potential – certainly, there are other UMS programs that challenge and reset the traditional parameters of concert patronage. Yet, what excites me is the possibility that these kazoos could be transformative, that they might fuse the roles of performer and listener into something more fluid and powerful, and that, in the near future, those who attend UMS events will feel invested in this organization and its offerings because UMS not only provides them with a chance to experience music from their seats but also create music with their kazoos.

There are so many superficial reasons why the UMS Kazoo Orchestra is a brilliant idea, but I believe this potential for empowerment is the most transcendent. Truly Render and the other leaders at UMS have found a constructive way to convert the ivory tower of jazz, world music, classical music, dance and theater performances into a dramatically more open space for presenters and audience members to interact essentially as peers. I feel imparting this kind of musical meaningfulness is imperative for the UMS to sustain and grow its audience, and the same is true for me and the, admittedly smaller, group of people who listen to my compositions.

That this enterprise does not feature my music in a conventional way is, to me, irrelevant because I believe my self is as much a part of my music as my music is an expression of my self. These days, there are few, if any, opportunities for living composers to meaningfully connect with about 800 people over the course of three hours. With my role as director of the UMSKO, I have been afforded the chance to build relationships with enormous numbers of excited, musically empowered, individuals – I intend to make the most of it, and so should you.

Questions about the UMS Kazoo Orchestra? Comment below. Interested in joining? Learn more.

British Classical Music Makes a Comeback

Photo: Alison Balsom, trumpet.

England has always been underrepresented in the history of Classical Music. There have been, of course, spurts when British composers or performers have made significant contributions to this tradition, but, more often than not, foreign musicians have dominated England’s musical world and drowned out the work of its native sons and daughters.

In the program of Alison Balsom’s April 20 performance, works dating from the period between English composer’s Henry Purcell’s death and English composer’s Edward Elgar’s ascent to international relevance exemplify a time when the most celebrated musical figures in England were outsiders, starting with George Frederic Handel.

Wandering interests