My Encounters with Gilberto Gil

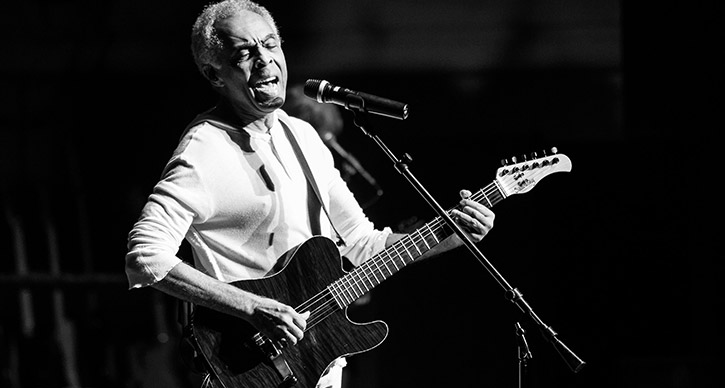

Photo: Gilberto Gil, pictured here at Hill Auditorium in 2012. He returns on April 4, 2014. Photo by Mark Gjukich Photography.

It is an honor and a pleasure to be asked by UMS to write about Gil. Yet it wasn’t so easy to know where to start. I decided not to try to cover his music career or work as Minister of Culture, but instead to write about my personal memories of Gil, some of our common friends, and what it was like to see him here in Michigan, after so many years since our last encounter.

Photo: Os Doces Bárbaros perform in 1976. Via.

Gil and I are from the city of Salvador, capital of the state of Bahia, Brazil. (Salvador is known as Bahia, just as one would say “New York” in reference to Manhattan). When I was in my early 20s, one of my best friends was Jovina, who is the niece of Caetano Veloso and Maria Bethânia, and another was Guto, who is Gal Costa’s brother. These three Bahian artists, Caetano, Maria Bethânia, and Gal Costa, together with Gil, comprised the famous group Os Doces Bárbaros (The Sweet Barbarians), which had made a spectacular entry onto the Brazilian music scene in the early 1970s, making a mark for themselves as brilliant artists and for Bahia as a font of musical talent. Through my friends, I met two of Gil’s daughters from his first marriage, Nara and Marília, and I became especially close to Sandra, Gil’s wife at that time, who was the mother of his children Pedro, Maria, and Preta.

Gil and I are from the city of Salvador, capital of the state of Bahia, Brazil. (Salvador is known as Bahia, just as one would say “New York” in reference to Manhattan). When I was in my early 20s, one of my best friends was Jovina, who is the niece of Caetano Veloso and Maria Bethânia, and another was Guto, who is Gal Costa’s brother. These three Bahian artists, Caetano, Maria Bethânia, and Gal Costa, together with Gil, comprised the famous group Os Doces Bárbaros (The Sweet Barbarians), which had made a spectacular entry onto the Brazilian music scene in the early 1970s, making a mark for themselves as brilliant artists and for Bahia as a font of musical talent. Through my friends, I met two of Gil’s daughters from his first marriage, Nara and Marília, and I became especially close to Sandra, Gil’s wife at that time, who was the mother of his children Pedro, Maria, and Preta.

Gil and Drão (Sandra’s nickname, and the title of one of Gil’s most beautiful songs) lived in the Costa Azul neighborhood. In the summer, their house was almost an obligatory stop for our group of friends. We stopped there on the way back from one of our favorite spots, Praia dos Artistas (the Artist’s beach) to hang out and chat, hear music, and have delicious food. I remember that little Preta, who is today a famous musical artist like her father, danced energetically among all of us in the middle of the living room to the sound of Brazilian Popular Music, most of which composed and interpreted by friends of the family.

In the 1980s, the city of Salvador was an effervescent center for the arts in Brazil, particularly known for the integration of its deep African heritage into its unique cultural production. This was true in all areas of culture, but there was no equal to the explosion of musical creativity and its national and international success. Bahian composers, musicians, and poets, created marvelous works and generously offered them to the world. There’s a saying in Brazil that “Bahians aren’t born, they are launched.”

As in the rest of Brazil, counter-cultural protests against the two-decade-long military dictatorship (1964-1985) had provided some of the stimulus for a uniquely creative generation. In 1969, during the most repressive phase of the dictatorship, Gil and Caetano Veloso had themselves been arrested and exiled for their brilliant, unconventional contributions to anti-authoritarian artistic expression. But the surge of artistic productivity in Bahia, and the city’s rise to prominence as the heart of Afro-Brazilian culture, reached its zenith after the dictatorship’s political opening in the late 1970s. Exiles returned home influenced by their experiences abroad and eager to re-immerse themselves in their country’s artistic milieu. In Gil’s case, I believe exile in London immersed him in the Afro-Caribbean music scene, inspiring him to seek a new Afro-Brazilian sound. After he came home in 1972, he contributed immensely to Bahia’s new cultural eminence.

I don’t know whether other young people like me in Bahia during the late 1970s and early 1980s were aware of what a privilege it was to be part of all of this, to live it as a matter of course. I remember saying to myself sometimes, “this is just too good.” In the summer, Bahia was THE place to be. It was hard to keep up with so many street festivals – those that combined religious and carnival processions with pre-carnival parties and dances – and public rehearsals of the carnival “blocks,” the floats and musical performances of the different groups of artists and revelers that created the biggest street carnival in the world. Gil’s “carnival block” was the beautiful Afro-Brazilian Afoxé Filhos de Ghandi (Sons of Ghandi).

There were also the festivities at the houses where different groups that practiced the Afro-Brazilian religion, Candomblé, worshipped. Most of my friends and I frequented gatherings of the Candomblé of Mãe Menininha do Gantois. And there were always marvelous concerts and music festivals, many featuring Gil and the other Doces Bárbaros, at the Castro Alves Theater and the Concha Acústica (Acoustical Shell) downtown, followed by bull sessions in bohemian bares such as Beco dos Artistas (Artists’ Corner) and the Afro-Brazilian Zanzi Bar, owned by Ana Célia and her siblings Danda, Macalé, Bené, and Neide, for whom Gil wrote the song “Lady Neide.”

Some of my memories of Gil are like photographs that remind me of Gil’s contagious tranquility. I once gave him a ride from the neighborhood of Barra to Pituba, about a 10-20 minute drive along the city’s coastline. At one point, the moon appeared in the sky, beautiful. I saw it when I turned around to talk to Gil. It seemed to be moving alongside the moon that Gil had painted onto his hair to promote his new record, Luar (“Moonlight”) (and I think there was a star on the other side of his head, but I’m not sure. Was there, Gil?). Another memory is of him sitting outside Caetano’s house in the urban neighborhood of Ondina, playing guitar and singing Gaivota (Seagull), as if no one else were there and at the same time as if everyone and the music and the singing were one thing. A picture of simplicity and harmony.

Perhaps my fondest memory of those times is of long days spent at beautiful beaches such as Porto da Barra, with its incomparable sunset. All of us loved the Porto beach, as we called the small stretch of sand. I was a devotee of Frescobol (fast-paced paddle ball, commonly played on Brazilian beaches), and played it all day long at that beach. Gil was a frequent spectator, always commenting on the game and telling us how much he loved to watch.

It’s been some thirty years since those days. By the mid-1980s, I had left Bahia for Rio de Janeiro, and was no longer present for every Bahian summer. Gil and my friend Drão eventually separated; Gil later married his current wife Flora (for whom he also wrote a beautiful song). Our group of friends was also no longer the same, with people having gone in different directions. I no longer ran into Gil, and, even before I moved to the United States, I hadn’t seen him for many years.

When UMS had the excellent idea of bringing Gil for a show at Hill Auditorium in 2007, I was very happy at the prospect of reliving some of the emotion of those magical times through his live performance of so many amazing songs. I thought he probably wouldn’t remember me, much less my name, after so many years and out of context. To my surprise and delight, when we met at the pre-show rehearsal at Hill, he stopped in front of me and we exchanged glances that revealed immediate recognition, although his expression suggested a high-speed re-winding of his memory to try to fit me somewhere in the past. After a moment, the energy of those times in Bahia manifested itself harmoniously. We both smiled, we hugged, and he asked: “Where’s the frescobol?”

Gilberto Gil performs at Hill Auditorium on April 4, 2014.