The Lives of Men – Guest Blog by Leslie Stainton

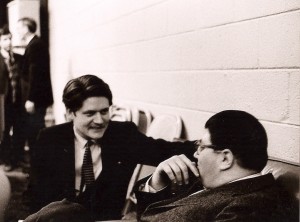

Photos from the UMS Archive. 1. L-R: Gordon Mumma with visiting composer Morton Feldman, ONCE Festival (1964), Ann Arbor. (Photo: Donald Scavarda) 2. Morton Feldman in Ann Arbor, ONCE Festival (1964). (Photo: Makepeace Tsao, courtesy of the Tsao Family)

Editor’s Note: Lobby contributor Leslie Stainton will guest blog the San Francisco Symphony American Mavericks festival throughout this weekend. Read her notes on Friday and Saturday.

Biography kept popping up. From Saturday’s pre-concert presentation on Charles Ives and his Concord Sonata, to the intros to each of the evening’s pieces, to the final, riveting and mercurial Concord Symphony, character and personality held center-stage throughout last night’s program. I’ve devoted huge parts of my life to writing and reading biography, so I generally don’t need convincing, but I found myself wondering at times last night whether it makes a difference to know, for example, that Carl Ruggles hated Brahms and destroyed much of his own work, or that Morton Feldman was a friend of Mark Rothko. In the end, I think it does.

Before each of the three pieces on Saturday’s program, Michael Tilson Thomas spoke briefly, and fondly, about its composer. Of the difficult and “craggy” Carl Ruggles, whose “Sun-treader” (1931) opened the evening, MTT said, “He spent most of his life pent-up in a small, one-room schoolhouse in Vermont with a piano a pot-bellied stove, and his adoring wife.” On weekends, Ruggles was visited by the likes of Thomas Hart Benton (who used the composer as a model for Ahab in his illustrated “Moby Dick”). Ruggles produced a slender oeuvre—just a dozen or so works—and they’re filled with defiance, rage, deep sorrow, and an aching passion, MTT said. “You instantly know it’s a statement by Carl Ruggles. So get ready.”

And he was right. With its huge and sober sounds, beautiful and raging all at once, “Sun-treader” seemed to me a palpable cry. I kept thinking of Icarus, striding toward the sun in his doomed chariot. And of Ruggles himself—a man who denounced the mainstream, an outlier unafraid of gods.

If Ruggles was a small man who wrote big, MTT said by way of introduction to the second work on the program, Morton Feldman was a big man who wrote delicate music. And then MTT launched into a brief imitation of Feldman—put on your best Brooklyn accent, and you’ve got it. “Dis work is de classiest ting Ay eva wrote,” Feldman (in MTT’s version) might have said about his “Piano and Orchestra” (1931), which MTT described as a cross between Webern and Duke Ellington. Elegant it was, as subtle and moving as a Rothko canvas (to which both MTT and the program notes likened Feldman’s work—MTT noting that “time” was Feldman’s “canvas”).

At one point during this languid piece, I felt as if I were hearing a deeply sophisticated “Peter and the Wolf,” so magically did the work illuminate each instrument in the orchestra, allowing us to focus on color and tone rather than the usual culprits, melody and rhythm. (Is it stretching things to suggest this functioned at least in part as a “biography” of an orchestra?)

Biography returned full-force in Charles Ives’s “Concord Symphony,” the last work on Saturday’s program, with its four sections devoted to four men who inhabited the legendary town where the American Revolution erupted—Emerson, Hawthorne, Alcott, Thoreau. MTT described the symphony as an epic, and it was. Big, bracing, with sudden and exquisite moments of tenderness nestled among passages of utter fury. I’ve always liked Ives, the Connecticut iconoclast who made his living selling insurance and persisted in writing works that few wanted to hear. But this piece brought him to life in ways I hadn’t heard before—and underscored the majesty and “Americanness” of his often nostalgic vision. A woman I spoke to after the performance summed it up: “This felt almost classical,” she said—especially after Friday night’s foray into the world of John Cage.

I do have one question about biography—where are the women in this series?

During intermission, I cornered the American composer and U-M faculty member Michael Daugherty, who was sitting a few rows in front of me, and asked him what these concerts meant to him:

Word has it that Carnegie Hall is having a tougher time filling its house for these concerts next week than Hill (a larger hall in a far smaller community). It’s a credit to Ann Arbor audiences, as Daugherty reminded me: