What makes music sacred?

Photo: On left, Apollo’s Fire, who perform Bach’s St. John Passion on March 15, 2016. On right, Simon Shaheen, who performs in Zafir on April 15, 2016. Photos courtesy of the artists.

Many people have a “sacred” song—one that especially resonates with or inspires. But what is the meaning of “sacred,” and what about music resonates so deeply? To try to get a sense of the answers to these questions, I asked surveyed a group of University of Michigan students about music that they consider sacred.

For some, a work calls to mind their religious origin and helps them seek a connection with a greater power. Hitomi, recent LSA music graduate, describes her sacred song: “The very first song that came to mind was Ave Maria. I feel that the lyrics evoke spirituality. It’s also a commonly known [religious] piece, so that’s why I associate the melody with connecting with spiritual existence. I experience a sense of serenity and calmness when I listen to Ave Maria. It’s like I’m getting cleansed from all of the negative feelings I might have at the moment.”

For others, like Abigail, a viola performance major, the “sacred” quality of music has to do with the context in which a piece was written. When asked about musical works that are sacred for her, Abigail explains: “Tchaikovsky’s 6th symphony is sacred to me; it’s very emotionally volatile. It’s especially dear to me because it was the last symphony Tchaikovsky wrote before he died, and there’s been so much discussion over what the symphony meant and whether it was a “suicide note.” I feel like the symphony is so emotionally intense that Tchaikovsky definitely had to have been going through something big in his life, but as far as I know, nobody’s really sure exactly what that was. I kind of like the mystery though — it leaves a lot more room for imagination.”

Monica, trumpet player in the Michigan Marching Band, holds a special affinity with the lyrics of her sacred song, Sara Bareilles’s Uncharted. Monica explains, “[The song] is about what to do when confronted with the unknown, when you are afraid of which direction to go in next, and about taking risks for yourself rather than follow what everyone else is doing. My favorite line is ‘compare where you are to where you want to be and you’ll get nowhere.’ [Uncharted is a song] of introspection, agency, and assurance. It suggests that ‘gold’ is not extra valuable just because everyone else seems to want it. Something ‘uncharted’ can be more valuable because you have the opportunity to make it mean as much as you want it to for yourself.”

Some songs are sacred because when we listen to them, they call to mind memories. Penny Stamps School of Art student and acoustic guitar enthusiast Hayden tells the story of her sacred song: “The Moon Song by Karen O made me cry the first time I heard it.” Hayden continues, “I was watching the movie Her on a long flight home from Ireland. I made it my mission to find out what the song [in the movie] was, and to learn it. I don’t really use my ukulele—you’ll usually find me jamming on guitar—but I picked it up so I could learn the Moon Song. [The song is] not even in my vocal range, but it gives me the warm fuzzies whenever I play it. I think that I like it so much because it brought me a dose of joy when I was sad to be a leaving a place where I wanted to stay, and on a mode of transportation that scares me to death. [The song] has that same dose of joy every time I plunk it out on my ukulele.”

Ryan, bassoon player in the Akropolis String Quartet, recalls the childhood memory tied to his sacred song, I Believe I Can Fly by R. Kelly. He says, “This might be a strange choice, especially because I will admit to knowing very few of the lyrics (just the famous chorus), and I haven’t listened to the studio recording of it in years. But, I associate that song with my deep childhood love of the movie Space Jam, starring Michael Jordan and Bugs Bunny. That movie taught me, in equal importance, the necessity of hard work and joy in the pursuit of my dreams (at the time, a career as a basketball player, but eventually music…). Since, the song has become a mental soundtrack much of the work I’ve put forth in life, and I have probably song the chorus out loud in front of people more than anything else I’ve ever heard. Sometimes I sing it in jest, sometimes I sing it sincerely—in private of course.”

Music can be sacred for many reasons. From Bach’s St. John’s Passion performed by Apollo’s Fire to the music of Andalucia in Simon Shaheen’s Zafir performance, there are many definitions of the sacred to explore through UMS performance in the upcoming season.

What’s your “sacred” music? What makes it sacred for you?

Zafir: World of the East

Simon Shaheen performs as part of the Zafir program on April 15, 2016 in Ann Arbor. Photo by Patrick Ryan.

The language of lyric, the spirituality of song: music embodies how a people live and feel, how they dance. As the Arabic World remains mysterious and misunderstood in the West, I encourage you to pause, be present, and immerse yourself in Zafir: the winds carrying the music of the Arabic World. Through his band Qantara (Arabic for arch), Simon Shaheen reveals the gateway to a new musical blending of cultures. Shaheen seamlessly infuses classical Arabic music with hints of Jazz, Western Classical, and Flamenco music, a blend that transcends the boundaries of both geography and genre.

Satisfying for the soul

“I want to create a world music exceptionally satisfying to the ear and for the soul,” says Shaheen. “This is why I selected members for Qantara who are virtuosos in their musical forms.”

Shaheen himself is a violin and oud virtuoso (the oud is a traditional Arabic instrument and the predecessor of the western lute). He is accompanied by guitarist, pianist, and vocalist Juan Pérez. The vocalist Nidal Ibourk provides a backdrop of classical Arabic vocal tones. These three combine their acoustic talent with the visual talents of Auxi Fernandez, a flamenco dancer. Fernandez and Rodríguez cultivate the essence of the flamenco tradition from Andalusia (southern Spain). Their cante jondo, or deep song, style is the most serious of the three styles of flamenco music. However, this duo’s tunes are lightened with sparks of Spanish folk music and punctuated with falsetas (short, instrumental measures between sung verses to accompany dance). The quartet’s combined talents as Qantara are represented in Zafir.

Shaheen, born in Palestine to a family of skilled musicians, emphasizes the influence traditional Arabic styles had on him as a child. Umm Kalthoum “used to come on the air on the first Thursday of each month,” Shaheen recalls. “I always remembered much of any new song she sang. The next morning I would…hum different parts for my father, and he would note them.”

World of the East

“Imagine a singer with the virtuosity of Joan Sutherland or Ella Fitzgerald, the public persona of Eleanor Roosevelt, and the audience of Elvis…You have Umm Kulthum,” says Virginia Danielson of Harvard Magazine. For many, Umm Kalthoum was the international sensation from the 1920’s to the 1970’s. The Egyptian-born actress, singer, and songwriter remains idolized across the Arabic World, given the nickname Kawkab al-Sharq, or World of the East. Her sensual and powerful contralto voice combines a sense of beauty with her own poetic lyrics, unfolding as a revelation of reality and experience to her audience. Her most captivating quality is the spontaneous creativity she exhibits in performance. As crowds listened to her improvise the same songs, they claimed to feel unique emotions each time: her emotions. This interpersonal relationship felt by her audience remains a defining quality of her distinct style and success as an artist, even after her death in 1975.

Umm Kalthoum’s style of improvisation is easy to spot in Shaheen. His album Taqasim: The Art of Improvisation in Arabic Music, underscores his talents as a collaborator and member of Qantara.

Qantara exists at the cultural interface between Flamenco and Arabic tradition, with emphasis on the longstanding legacy of Umm Kalthoum. “If it [Arabic culture] is kept as a kind of puzzle…then definitely there will be hate and fear,” says Shaheen.

From Spain to Arabia, and everything in between, Qantara acts as an archway welcoming audiences into a surprisingly palatable and unusual world. What better way to understand cultures than through music, the language we use when words fail. As such, I invite you to uncover an artfully crafted performance that bridges and collides worlds of tradition together, right here in Ann Arbor in the Michigan Theater.

See Zafir: Musical Winds from North Africa to Andalucía on April 15, 2016 at the Michigan Theater in Ann Arbor.

References

“Bridges.” Interview by Marty Lipp. RootsWorld 2001: n. pag. Roots World. Web. 5 Jan. 2016.<http://www.rootsworld.com/interview/chava-simon.html>.

Campbell, Kay H. “Biography.” Official Website of Simon Shaheen. N.p., n.d. Web. 05 Jan. 2016.

Campbell, Kay H. “Simon Shaheen.” Aramco World May-June 1996: n. pag. Aramco World. Web. 5 Jan. 2016.

Danielson, Virginia. “Umm Kulthum Ibrahim.” Harvard Magazine. Harvard Magazine Inc., 01 July 1997. Web. 05 Jan. 2016.

Explore: Connections Between UMS and U-M Museum of Art

Visual and performing arts have a close relationship. We asked our partners and friends at UMMA (U-M Museum of Art) to link performances on the UMS season with visual art works that are part of the museum’s permanent collection.

Related performance: Tanya Tagaq in concert with Nanook of the North

February 6, 2016

Artwork: Kenojuak Ashevak (Canadian, 1927-2013). Sun Owl, 1963. Stonecut print on paper. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Eugene B. Power, 1964/2.103

Artwork: Kenojuak Ashevak (Canadian, 1927-2013). Sun Owl, 1963. Stonecut print on paper. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Eugene B. Power, 1964/2.103

Like Tanya Tagaq, Kenojuak Ashevak was from Nunavut and her art was inspired by her Inuit experience. She often depicted animals from the Arctic such as this owl, but, also like Tagaq, she relies on her creativity and imagination. Ashevak explained that she drew as she thought, and so she produced spontaneous and improvisatory images.

Related performance: Camille A. Brown & Dancers: Black Girl — A Linguistic Play

February 13, 2016

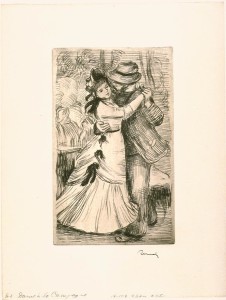

Artwork: Pierre Auguste Renoir (French, 1841-1919). Dance in the Country, c. 1890

Artwork: Pierre Auguste Renoir (French, 1841-1919). Dance in the Country, c. 1890

Soft-ground etching on paper. Museum Purchase, 1959/1.102

In Renoir’s beloved image of country dance we see an earlier century’s ritual of recreation. Although more restrained than contemporary dance, it represents social dance, one of the inspirations for choreographer Camille Brown’s work.

Related performance: Nufonia Must Fall

March 11-12, 2016

Artwork: P. Grasnick (n.d.). Aelita, 1924

Artwork: P. Grasnick (n.d.). Aelita, 1924

Lithograph on buff woven paper, laid down on canvas. Gift of James T. Van Loo, 2013/2.233

This poster is for the movie Aelita, which is often called the first Soviet science fiction film, created during the sometimes hope-filled beginnings of the Soviet Union. A mysterious radio message is beamed around the world, and among the engineers who receive it are Los, the hero of the film. Aelita is the daughter of Tuskub, the ruler of a totalitarian state on Mars. With a telescope, Aelita is able to watch Los who obsesses about being watched by her. He builds a spaceship and travels to Mars where he is thrown in prison, begins a proletarian uprising and experiences the confusion of reality and fantasy. While Nufonia Must Fall is no sci-fi film, it is based on a graphic novel of the same title, and viewers might find similarities between the genres.

Related performance: Gil Shaham Bach Six Solos

with original films by David Michalek

March 26, 2016

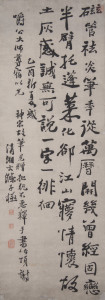

Artwork: Shitao (Shih-t’ao; Chinese, 1642-1707) Ode on a Wanli-era Imperial Brush Ink on paper, 1705. Museum purchase made possible by the Margaret Watson Parker Art Collection Fund, 1965/2.75.

Artwork: Shitao (Shih-t’ao; Chinese, 1642-1707) Ode on a Wanli-era Imperial Brush Ink on paper, 1705. Museum purchase made possible by the Margaret Watson Parker Art Collection Fund, 1965/2.75.

Taking an honored and beloved corpus of music from the past, Gil Shaham transforms its familiar beauty into a fresh, contemporary work of art. Similarly, Shitao receives a beautiful gift, a porcelain-handled calligraphy brush, from an earlier generation and uses it to write a poem and create a calligraphic masterpiece. The era and form are new but the inspiration is classic.

Related performance: Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán

April 1, 2016

Artwork: Artist Unknown, Mexican, Colima Culture Seated Figure, c. 700 Terracotta Museum purchase made possible by a gift from Helmut Stern, 1983/1.355Artist Unknown, Mexican, Colima CultureSeated Figure, c. 700TerracottaMuseum purchase made possible by a gift from Helmut Stern, 1983/1.355

Artwork: Artist Unknown, Mexican, Colima Culture Seated Figure, c. 700 Terracotta Museum purchase made possible by a gift from Helmut Stern, 1983/1.355Artist Unknown, Mexican, Colima CultureSeated Figure, c. 700TerracottaMuseum purchase made possible by a gift from Helmut Stern, 1983/1.355

This lovely terracotta seated figure is an example of the native arts and culture celebrated by Mexican visual and musical artists. Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán transform a regional folk music into a world-class art form.

Related performance: Zafir: Musical Winds from North Africa to Andalucia

April 15, 2016

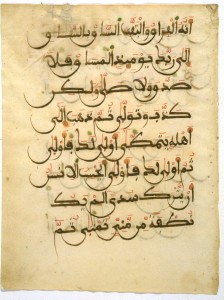

Artwork: Artist Unknown, North Africa Qur’an manuscript leaf in Maghribi script, 13th century Ink, red ochre, paper Museum Purchase, 1959/1.146

Artwork: Artist Unknown, North Africa Qur’an manuscript leaf in Maghribi script, 13th century Ink, red ochre, paper Museum Purchase, 1959/1.146

For Muslims, Arabic script, representing the language of the Qur’an, is a thing of sublime beauty. This page is written in a script called Maghribi, a variation of the earlier, angular, Kufic script. Maghribi features sweeping curves that loop across the page and was developed in North Africa and Spain. This Qur’an page combines traditions of the Middle East, Spain and North Africa as does the music of Simon Shaheen and Zafir.

Interested in more? Visit the U-M Museum of Art today.