Perspectives on Melody in Dvorak, Tchaikovsky, and Vasks

Artemis Quartet perform in Ann Arbor on April 19, 2015. Photo by Molina Visuals.

The Artemis Quartet’s program features two stalwarts of their usual repertoire alongside a recent work by one of Europe’s leading contemporary string composers, Peteris Vasks. Born, educated, and based in Latvia, Vasks began his musical life as a bassist before transitioning to composition in the 1970s. His experiences as a string player are likely responsible for the plentitude of pieces for string ensembles among his output. More importantly, his familiarity with the sound of string instruments equips him well to write highly evocative, highly expressive string music.

A strong melodic focus

While it may seem that Vasks, Dvořák, Tchaikovsky have little in common beyond the fact they are all European composers, this is not wholly the case. All three create music with a strong melodic focus that gravitates toward a clear lyrical style. Of course, Vasks enjoys and employs more freedom than Dvořák or Tchaikovsky, whose aesthetic choices were effectively dictated by a syntax of musical ideas shared among essentially all contemporaneous European composers. Indeed, melody is a de rigeur element of nineteenth century music, and Tchaikovsky is regarded as one of the best melodists in history. The Quartet No. 1 in D major (1871), part of the Artemis Quartet’s April 2015 program, certainly lives up to his reputation, although its tunes may not be as famous as those featured in Tchaikovsky’s ballets.

More interesting are the melodic experiments present in Dvořák’s Quartet in F Major, “American” (1893), which contains the pentatonic scale in abundance. The presence of this five-note scale, which also appears prominently in Dvořák’s Symphony No. 9, “From The New World” (1895), may have garnered the quartet’s nickname, as the pentatonic melodies suggest non-white American folk music. Dvořák wrote fondly of African-American music, which he heard while living in the United States, and it’s reasonable that he may have tried to refer to this tradition in the pieces he composed during this period.

Thinking beyond the movement

Although Vasks values melody in a very traditional sense, he treats it more dynamically than Dvořák or Tchaikovsky. As you will hear, Vasks thinks beyond the movement of one note to another; he develops color, register, and texture as well. Vasks’ string orchestra work Musica Dolorosa (1983) demonstrates this quality very clearly, moving from a mournful, romantic melody to an intense, aleatoric swarm of dissonance. Although there is no existing recording of Vasks’ String Quartet No. 5 (2008), his other quartets possess these same characteristics, despite the more limited instrumentation. Thus, it seems fair to expect the same in his more recent work.

In program notes written for his publisher, Vasks describes elements of his dramatic String Quartet No. 5 as, “atmospheric”, “a cry of utter desperation”, and, “a forgiving, loving look at a world tortured by grief and contradictions.” Structurally speaking, this quartet marks a departure for Vasks. String Quartet No. 5 has only two movements – being present and so far…yet so near – while the previous four all have at least three, with his String Quartet No. 4 (199) sporting five wildly contrasting movements. It will be interesting to see whether the seemingly condensed form of the String Quartet No. 5 manifests a unified and cohesive piece, or if the two titled movements simply represent two adjacent, yet individual, regions of diverse, free, and expressive musical ideas.

Interested in more? Explore our listening guide to the evolution of the string quartet.

UMS Playlist: Classical Music Old Friends from Communications Director Sara Billmann

This post is a part of a series of playlists curated by UMS staff, artists, and community. Check out more music here.

Photo: San Francisco Symphony, who’ll perform Mahler Symphony No. 7 at Hill Auditorium on November 13, 2014.

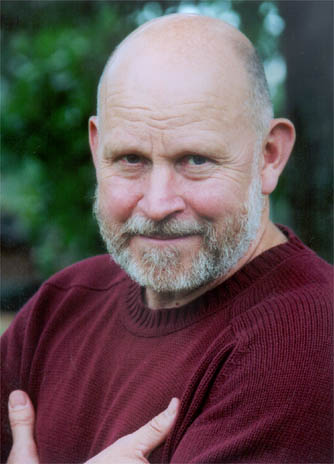

I grew up in a small town in Wisconsin and studied piano from age 5 and oboe from age 11 in a family where music was central. My mother was a piano teacher, taught vocal music in the public schools, and directed her church choir; my sister became a professional horn player and freelances in New York; and even my father, a middle school math teacher for over 35 years, participated by periodically singing in a local chorus and playing the baritone in a local German band.

Because of that background, I was constantly exposed to classical music, but there are some pieces that stand out as having made an incredible impression on me as a young musician from the time of middle school until early college. While my tastes have certainly evolved over the years, these are still my “old friends” that I love to revisit and never grow tired of.

Mahler’s Symphony No. 1: I fell in love with this piece in 7th or 8th grade and can remember being home alone, turning out all of the lights, and lighting candles to listen to an early James Levine recording in a complete solitude. Mahler could take me to a place of incredible peace, only to be interrupted by the bombastic beginning to the fourth movement, which always scared the bejeezus out of me. To this day, I’m still a pushover for Mahler and the emotional range that his symphonic and vocal works explore.

Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 2: As an oboe player, I loved playing along with the record of Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 2. It’s such a joyful piece, fun to play, but also fun to listen to. My sister would occasionally play along with me, adapting the trumpet part for horn.

Beethoven Symphony No. 9: I played this work in high school with my local orchestra (with my sister also in the orchestra and my dad in the chorus). Being immersed in the sound of full orchestra plus chorus all on one stage was a remarkable experience for a young musician.

Tchaikovsky’s Capriccio Italien: While seemingly not performed very often these days, this is one of the first classical music pieces that I can remember falling in love with, probably in about 5th or 6th grade. If I remember correctly, we had an LP that included Capriccio Italien, Marche Slave, and 1812 Overture, but it was always Capriccio Italien that I returned to time and again.

Dvorák’s “New World” Symphony: Dvorák’s works are readily accessible and easy to listen to, but certainly not “easy listening.” A recent New York Times article talked about how Dvorák ended up in Iowa, where he wrote this symphony.

Schubert: When I left Wisconsin to move to Ann Arbor to attend the University of Michigan, my sister (then a senior at the University of Wisconsin) made a couple of cassette tapes for me of some of her favorite pieces by Schubert, which I listened to constantly for several years. Among the highlights: Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau singing Die schöne Müllerin, the “Trout” Quintet and the Rondo in D Major for piano duo. Sadly, her tape ran out in the middle of the work, and it was years before I heard how it ended.

Shostakovich: Michael Gowing, the former UMS ticket office manager who retired over a decade ago, considered Shostakovich a “B movie composer,” but I always loved his works. While in college here at U-M, I heard Mariss Jansons conduct the Oslo Philharmonic in Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 7 with its Bolero-like theme, and it was an extraordinary event that began a lifelong appreciation for Shostakovich’s works. I still love listening to the string quartets (especially Nos. 7, 8, and 15), his piano quintet, and many of the symphonies. The Kirov Orchestra’s performance of his Symphony No. 13 several years ago left me in tears, completely shaken at the power of music.

Listen to various selections and recordings of Sara’s picks on Spotify:

What did you think about this playlist? Share your thoughts or song suggestions in the comments below.

Glimmers of Light and Dark with the London Philharmonic

The London Philharmonic’s concert this Tuesday, December 6, in Hill Auditorium, features an intriguing program of the familiar, dramatic and mystifying. With Mozart’s beloved Violin Concerto no. 5, Matthias Pintscher’s seething and violent towards Osiris (2005) and Tchaikovsky’s rarely performed “Manfred” Symphony, the performance will begin in a delicate, comfortable musical environment and then take the audience on a wild ride through space and time, concluding with a prodigious and fantastical tone poem.

The London Philharmonic’s concert this Tuesday, December 6, in Hill Auditorium, features an intriguing program of the familiar, dramatic and mystifying. With Mozart’s beloved Violin Concerto no. 5, Matthias Pintscher’s seething and violent towards Osiris (2005) and Tchaikovsky’s rarely performed “Manfred” Symphony, the performance will begin in a delicate, comfortable musical environment and then take the audience on a wild ride through space and time, concluding with a prodigious and fantastical tone poem.

The Mozart concerto opening the evening’s music is an admittedly incongruous aperitif to the Pintscher and Tchaikovsky, simply because those later works are rooted in extra-musical narratives, as I will explain later. The Violin Concerto no. 5 is better known as one of Mozart’s greatest achievements in the concerto repertoire, seamlessly melding technical demands on the soloist with his typically beguiling melodic ideas. According to ClassicalArchives.com, this work may be the most commonly performed violin concerto in classical music. Though the piece employs a broadened dramatic scope – and even includes the direction “aperto”, something Mozart usually limited to his operatic scores – the piece is pro forma, lovely Mozart, complete with an indefatigable supply of charming melodies to delight any and all listeners.

Try to savor the halcyon mood of the Mozart as much as possible, be cause towards Osiris and the “Manfred” Symphony could not be two more different works, both in terms of their affect and inspiration. Based on Egyptian mythology, Matthias Pintscher’s towards Osiris was commissioned by conductor Simon Rattle for a 2005 recording of Gustav Holst’s The Planets, released on the EMI Classics Label. Maestro Rattle’s aim was to have a group of living composers create a set of new works to pair with The Planets, which he dubs “The Asteroids”. Though there are no galactic connotations in towards Osiris, the piece does unfold like view a series of disconnected constellations, which eventually become more unified thanks to a gradually energizing percussion part.

Pintscher’s music is uncommonly brutal, an affect that makes sense in light of the myth on which the composer based the piece. In a documentary EMI produced as part of their recording project with Simon Rattle, Pintscher describes the Egyptian myth of Osiris wherein the God is torn into pieces that are ultimately collected and reanimated by his wife, Isis. Towards Osiris emulates this story with startling precision. As I already noted, the musical ideas are disparate and violent, seemingly representative of Osiris’ dismembered remains The percussion part is crucial to the motivation of the music’s activity, just like the flapping of Isis’ wings as she attempts to bring her deity husband back to life. In the end, the music surges with the increasingly active lifeblood of the percussion part and the once isolated ideas of the work’s beginning come together in one sonic mass.

Tchaikovsky’s “Manfred” Symphony is similarly based on an extra-musical program, though the connection here is a little more deliberate. The narrative on which Tchaikovsky based the work is an adaptation of the supernatural-themed poem “Manfred” by Lord Byron created by the Russian critic Vladimir Stasov. In turn, Stasov’s inspiration came from Hector Berlioz’s Harold in Italy, an enormously popular work in Russia for which Stasov imagined the “Manfred” Symphony as a sort of sequel. Tchaikovsky’s participation in the project came accidentally. Initially, Stasov wished to work with Mily Balakirev, but the composer refused and (thankfully) recommended Stasov approach Tchaikovsky, instead.

Like Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique, the “Manfred” Symphony represents its program through musical ideas, some clearer than others. The long, dark opening movement is meant to evoke the desolate condition in which we meet Manfred, walking alone through the Alps as an exile, searching for relief from his regrets and memories. Themes emerge to represent the characters in the story, Manfred and his love Astarte, but do no reappear under the conventional pretexts we often see in Tchaikovsky’s works, including the beloved fantasy-overture Romeo and Juliet. Rather, Tchaikovsky writes the “Manfred” Symphony with liberal formal ideas, focusing on the music’s dramatic character over traditional structural requirements.

To this extent, the “Manfred” Symphony is very much the Richard Strauss tone poems Don Quixote or Ein Heldenleben: large, multi-movement works conceived to highlight the facets of a detailed extra-musical narrative. Armed with an uncommon sense of thematic and formal freedom, Tchaikovsky’s score is unpredictable and compelling, reflecting the emotional turmoil of Byron’s Manfred with a wide palette of orchestral colors and a multitude of captivating melodies (the latter, of course, is something we always expect with Tchaikovsky). This colorful and dramatic personality is most obvious in the final movement wherein Manfred finds himself in an underground “Hall of Evil”. Symbolically, an organ enters and signals our hero’s glorious acceptance of death and the end of his torment (listen closely to the bassoons and cellos in the piece’s final bars and you may be able to hear a very obvious allusion to the final movement of Symphony Fantastique, a work Tchaikovsky must have greatly admired).