UMS Artist in Residence Update: Tanya Tagaq and the Poetry of Ecojustice

Editor’s note: Russell Brakefield is a poet and one of our 2015-2016 artists in residence. As part of this program, artists in residence attend UMS performances to inspire new thinking and creative work within their own art forms. Russell attended UMS Night School: Constructing Identity, featuring Taylor Mac and Tanya Tagaq, as well as Tanya Tagaq’s performance with Nanook of the North. Below is his response to the class and performance:

In her conversation as part of the UMS Night School’s series Constructing Identity it became apparent to me that Tanya Tagaq, in addition to being a well-renowned Inuk throat singer, is also a poet. Her work, she said, is interested in better representing the intense relationship her people share with the land. “The land eats us the way the city eats you,” she said. “Even our thread comes from sinew. We have a diet of souls.” What language, I thought. What voice! What purpose!

Pictured from Left to Right: Clare Croft, Taylor Mac, Tanya Tagaq, Jim Leija at UMS Night School.

The first issue of Poetry Magazine in 2016 carries with it the enigmatic theme of Ecojustice. In the introduction to the issue Melissa Tuckey writes that Ecojustice poetry “lives at the intersection of culture, social justice, and the environment. Aligned with environmental justice activism and thought, Ecojustice poetry defines environment as the place in which we work, live, play, and worship. It is poetry born of deep cultural attachment to the land and poetry born of crisis. It is poetry of interconnection.” This then—it seems to me—is the poetry of now, art that is essential, art that is necessary. Or perhaps this is the poetry of the perpetual now, evoked over and again in the ever-changing rush of violations against the environment, against marginalized peoples, the coupled plague there.

No matter the exact definition or the flourish of devastations that necessitates a genre such as Ecojustice, I’d like to place Tanya Tagaq and her breathtaking Nanook of the North performance squarely under this distinction. And her performance clarifies something else that I believe is crucial for art using this term—this performance was not only important but also transformative. It asked of its audience to feel as much as it asked of its audience to know. During her conversation for the UMS Night School Tagaq discussed her interest in inviting her audience to breathe, to leave the theater breathing in the experience of her people. She discussed her hope that this bodily reaction to her work would juxtapose with what the audience saw on the screen and disrupt what they knew already about the film Nanook of the North.

Photo: Tanya Tagaq. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Photo: Tanya Tagaq. Photo courtesy of the artist.

The 1922 documentary is a spectacular work of art on its own, but it is also deeply afflicted with the stereotypes of its time. The film follows an Inuk man through his daily life in the Canadian Arctic. Often thought of as the first full-length documentary, the film was the source of an influx of dramatic ethnographic documentaries in the twentieth century. A New York Times review of the film from the year of its release praises filmmaker Robert J. Flaherty’s skill and innovation, which allows Nanook’s life to be “filled out, humanized, touched with the humor and other high points of a recognizably human existence. Thus there is body, as well as dramatic vitality, to Nanook’s story.”

But despite these groundbreaking cinematic achievements, this film also serves as a lasting reminder of the sneaky hand of history, the way people and places were routinely misrepresented or exploited in the name of art and entertainment by a dominating class of public artists. As a lasting and widely disseminated piece of art, the film perpetuates cultural insensitivity in the way that much popular culture of certain time periods does. Even as an effort of recording the practices of a people on the edge of displacement, the film raises questions for the artist and the archivist that harken back to the earliest conflicts with anthropological involvement.

Tanya Tagaq’s performance responds to both the positive impressions of the film and the negative. She embrace’s Nanook of the North for its representation of the hardships of life for her people. She draws connections between the landscape that is depicted so vividly in the film and the rich heritage and power of her people. But she also calls attention to the way the movie wrongly depicts Inuit culture, the stereotypes represented there, the omissions made out on the ice.

Her Nanook of the North performance combines traditional throat singing with other vocal textures, breath work, and movement. Tagaq’s performance is visceral, athletic, and jarring. And the performance does something the film cannot do by itself. She is not simply saying, look at this thing that is both beautiful and deeply flawed. She provides, in her accompaniment, a filter that accounts for cultural context. She provides a filter for our renewed sense of duty towards people, landscapes, and the relationships between the two. She makes art that ruptures the intellectual response to colonial fallout and instead invites audiences to re-read and re-feel the film. She invites us to breathe.

Photo: Tanya Tagaq. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Photo: Tanya Tagaq. Photo courtesy of the artist.

I’m drawn to the idea of Ecojustice in part because it attempts to collapse the gulf between intellectual and emotional response. It also attempts to collapse the gap between social issues and issues of ecology. It is about connectivity. Somewhere amidst the heartbeat of Tagaq’s performance— drummer Jean Martin and violinist Jesse Zubot add a wild soundscape to the piece—I found my attention divided between the music and the film. I was drawn back and forth between the film and Tagaq’s winding, dramatic performance. I felt myself giving over to her incredible vocal work and at times needed to close my eyes. Tagaq was representing everything at once— the beauty and hardship of her people, the injustices there, the wreck of the land, her own place in the history of all this.

This performance made me thankful for the poets I read in my youth, poets like Wendell Berry and, more recently, poets like C.D. Wright. These poets, like Tagaq, showed me the potential of art to speak to the mistakes of history and the troubles of now. This type of work offers artists an opportunity to reclaim the past and unwind it, unfold it.

All art is a form of translation and all translation is a form of theft. And yet here Tanya Tagaq translates the miswritten story of the past and reaches into future, into the violent landscape of possibility we call innovation.

Interested in more? Follow the adventures and process of other UMS Artists in Residence.

UMS Night School: Constructing Identity Together – Session 4 Recap

Please note: This post is a part of series about the free and open to the public UMS Night School. UMS Night School: Constructing Identity runs January 18-February 15, 2016.

This past Monday, I attended my second UMS Night School session. For this week’s session, we discussed this past weekend’s performances by Tanya Tagaq and Taylor Mac.

The discussion focused on how Taylor Mac and Tanya Tagaq made their performances accessible and relatable to audiences; some of the UMS Night School participants noted that Taylor and Tanya’s performances were “welcoming” and “inviting.” Talk about constructing identity together! These two artists really went above and beyond in engaging their audiences, whether it was physically (like Taylor Mac) or emotionally (like Tanya Tagaq), or both!

We then moved into a discussion of upcoming performance of Camille A. Brown’s Black Girl–Linguistic Play, occurring this Saturday, February 13, 2016 at 8 pm in the Power Center. This time around, the discussion was lead by guest speakers Robin Wilson (Associate Professor of Dance) and three University of Michigan students in the School of Dance: Michael Parmelee, DeeDee Fattore, and Selena Moeljadi, all of whom had the experience of being involved in Camille A. Brown’s City of Rain.

Camille A. Brown’s City of Rain, performed by the Mason Gross School of the Arts.

While the video above does not feature our awesomely-talented guest speakers, it does feature some of the emotion that our speakers said they’ve learned to channel in their performance of City of Rain, which was featured in the University of Michigan Dance Department’s most recent showcase, Momentum, which ran from February 4-7, 2016.

Robin Wilson shared her experience of what it was like to be the Rehearsal Director for City of Rain, while the students shared their experience of being in the midst of City of Rain.

What did you learn?

Jim asked the guest speakers what they learned from their experiences of City of Rain. Students mentioned “grief” and “sadness” in the physical movements that they experienced. They had to dig deep to successfully understand those (and other) emotions in the choreography. The students could’ve simply emulated the emotion that Camille A. Brown suggested, however, this would be similar to an instrumentalist emulating the emotion that a composer intended in a piece, or similar to an actor emulating emotions onstage. Sure, that might look and sound fine and dandy, but it would be different from the real thing. The real thing is when students draw upon their own grief, their own sadness, their own emotion to make Brown’s choreography much more powerful.

Robin Wilson, as Rehearsal Director, assisted in this process. She summed it up nicely: “We want a cake with the rum soaked through [not a cake with frosting on top]!”

Student DeeDee Fattore said that in her research she has found that she really loves that Brown’s work is so relatable; anybody – dancer or audience member – can relate to the movements and emotions in her work. Fattore says this is something that she would like to be able to do in her own work as a choreographer.

Black Girl – Linguistic Play

We shifted gears toward the end of the class to talk about Camille A. Brown’s Black Girl – Linguistic Play, which will be performed this Saturday, February 13, 2016 at 8 pm in the Power Center.

We shifted gears toward the end of the class to talk about Camille A. Brown’s Black Girl – Linguistic Play, which will be performed this Saturday, February 13, 2016 at 8 pm in the Power Center.

Asked what “Black Girl” really means, Wilson pointed out that it’s an important specificity. “Black” in this context is vernacular, being unapologetically oneself, and also implies that the work is perhaps intentionally less refined than and less conforming to the African American cultural identity. “Girl” in this context is associated with sass, playfulness, being yourself. Camille uses the title “Black Girl” to hone in on the identity and experience of being a “Black Girl.” Tickets to the performance are still available.

This session really pumped me up for the performance this weekend, and I walked out of the Alumni Center feeling inspired and full of new perspectives and insights.

I’m telling you, if you are looking to expand your horizons, these classes are amazing! There is only one session left, so join us next Monday, February 15, at 7 pm in the Alumni Center for Reflection and Graduation.

UMS Night School: Constructing Identity – Session 3 Recap

Please note: This post is a part of series about the free and open to the public UMS Night School.UMS Night School: Constructing Identity runs January 18-February 15, 2016.

On Monday February 1, I attended my first UMS Night School session. For this particular week, we were lucky to have special guests Tanya Tagaq, performing February 2 at 7:30 pm, and Taylor Mac, performing February 5-6 at 8pm. The turnout for this session was high and the crowd was excited and interested to hear what the artists had to say in this casual yet upbeat interview.

Jim Leija (UMS Director of Education and Community Engagement) and Clare Croft (U-M Assistant Professor of Dance).

Pictured from Left to Right: Clare Croft, Taylor Mac, Tanya Tagaq, Jim Leija

Pictured from Left to Right: Clare Croft, Taylor Mac, Tanya Tagaq, Jim Leija

Taylor and Tanya took turns talking about their upbringing. They were both expected to adhere to the social norms of their respective communities. At a certain point, both Taylor and Tanya were tired of being told to follow the rules and decided to rebel by branching out and letting their true identities be known. Taylor stated, “When I am on stage you listen to me, I am in charge!”

What is your artistic family tree?

Both Taylor and Tanya were influenced by music and other art forms at a very young age, and neither of them are classically trained musicians. Improvisation is important to both of them as performers, because it makes each show unique and special in its own way. Both artists use their performances as a way to connect with the audience in a profound way and always have an important message they hope to portray.

The floor was then opened up to audience questions. It was refreshing to learn that both Taylor and Tanya have changed over time as performers and to learn about what their ultimate goals were at a younger age as well as what they are now. As a student, I have sometimes been scared of becoming pigeon-holed into one career mindset when in reality there are multiple options and ways to achieve my ultimate goals.

The class was a fun and awesome learning experience; it was interesting to gain more perspective about different upbringings and lifestyle choices that people from vastly different regions can have.

UMS Night School sessions are free and open to the public. Drop into one or attend them all, no registration required.

Don’t miss the next class on Constructing Identity Together: Artists and Audiences with specials guests: Robin Wilson, Michael Parmelee, Daniele Fattore, and Salina Moeljadi, Monday February 8 at 7:00 pm.

Study Up: Tanya Tagaq Teaches You to Throat Sing

Photo: Tanya Tagaq. By Ivan Otis.

Photo: Tanya Tagaq. By Ivan Otis.

“Nobody, anywhere, sounds like she does,” said the Globe and Mail of Tanya Tagaq, who performs at the Lydia Mendelssohn Theatre on February 2, 2016.

Tagaq has received many awards, but one of our favorites is Rolling Stone magazine’s “Best Scream” award for her performance at Bonnaroo festival. Her Ann Arbor performance features the Inuit throat singer accompanying a screening of Nanook of the North (1922) with a live score.

How to throat sing

Throat singers produce more than one pitch at a time through the positioning of the lips, tongue, larynx, and jaw. Though unfamiliar to most Western ears, throat singing is part of a number of global musical traditions including those of central Asia, South Africa,

and northern Canada. Inuit throat singing originated as a way for women to entertain themselves and engage in friendly competition while men were away hunting. Two women face one another closely and improvise musical patterns; the first one to laugh or run out of breath loses.

Watch this video to learn more about Inuit throat singing in its traditional form:

In this video, Tanya Tagaq explains the vocal processes used to create the basic sonic building blocks of Inuit throat singing. She usually tells her students to “spend one year trying to sound like their dog.”

Videos excerpted from UMS Learning Guide for Tanya Tagaq.

Tanya Tagaq performs at the Lydia Mendelssohn Theatre on February 2, 2016.

Explore: Connections Between UMS and U-M Museum of Art

Visual and performing arts have a close relationship. We asked our partners and friends at UMMA (U-M Museum of Art) to link performances on the UMS season with visual art works that are part of the museum’s permanent collection.

Related performance: Tanya Tagaq in concert with Nanook of the North

February 6, 2016

Artwork: Kenojuak Ashevak (Canadian, 1927-2013). Sun Owl, 1963. Stonecut print on paper. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Eugene B. Power, 1964/2.103

Artwork: Kenojuak Ashevak (Canadian, 1927-2013). Sun Owl, 1963. Stonecut print on paper. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Eugene B. Power, 1964/2.103

Like Tanya Tagaq, Kenojuak Ashevak was from Nunavut and her art was inspired by her Inuit experience. She often depicted animals from the Arctic such as this owl, but, also like Tagaq, she relies on her creativity and imagination. Ashevak explained that she drew as she thought, and so she produced spontaneous and improvisatory images.

Related performance: Camille A. Brown & Dancers: Black Girl — A Linguistic Play

February 13, 2016

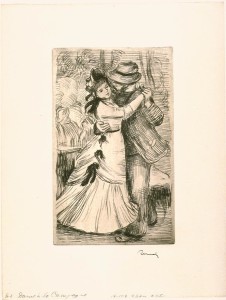

Artwork: Pierre Auguste Renoir (French, 1841-1919). Dance in the Country, c. 1890

Artwork: Pierre Auguste Renoir (French, 1841-1919). Dance in the Country, c. 1890

Soft-ground etching on paper. Museum Purchase, 1959/1.102

In Renoir’s beloved image of country dance we see an earlier century’s ritual of recreation. Although more restrained than contemporary dance, it represents social dance, one of the inspirations for choreographer Camille Brown’s work.

Related performance: Nufonia Must Fall

March 11-12, 2016

Artwork: P. Grasnick (n.d.). Aelita, 1924

Artwork: P. Grasnick (n.d.). Aelita, 1924

Lithograph on buff woven paper, laid down on canvas. Gift of James T. Van Loo, 2013/2.233

This poster is for the movie Aelita, which is often called the first Soviet science fiction film, created during the sometimes hope-filled beginnings of the Soviet Union. A mysterious radio message is beamed around the world, and among the engineers who receive it are Los, the hero of the film. Aelita is the daughter of Tuskub, the ruler of a totalitarian state on Mars. With a telescope, Aelita is able to watch Los who obsesses about being watched by her. He builds a spaceship and travels to Mars where he is thrown in prison, begins a proletarian uprising and experiences the confusion of reality and fantasy. While Nufonia Must Fall is no sci-fi film, it is based on a graphic novel of the same title, and viewers might find similarities between the genres.

Related performance: Gil Shaham Bach Six Solos

with original films by David Michalek

March 26, 2016

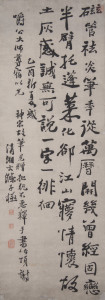

Artwork: Shitao (Shih-t’ao; Chinese, 1642-1707) Ode on a Wanli-era Imperial Brush Ink on paper, 1705. Museum purchase made possible by the Margaret Watson Parker Art Collection Fund, 1965/2.75.

Artwork: Shitao (Shih-t’ao; Chinese, 1642-1707) Ode on a Wanli-era Imperial Brush Ink on paper, 1705. Museum purchase made possible by the Margaret Watson Parker Art Collection Fund, 1965/2.75.

Taking an honored and beloved corpus of music from the past, Gil Shaham transforms its familiar beauty into a fresh, contemporary work of art. Similarly, Shitao receives a beautiful gift, a porcelain-handled calligraphy brush, from an earlier generation and uses it to write a poem and create a calligraphic masterpiece. The era and form are new but the inspiration is classic.

Related performance: Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán

April 1, 2016

Artwork: Artist Unknown, Mexican, Colima Culture Seated Figure, c. 700 Terracotta Museum purchase made possible by a gift from Helmut Stern, 1983/1.355Artist Unknown, Mexican, Colima CultureSeated Figure, c. 700TerracottaMuseum purchase made possible by a gift from Helmut Stern, 1983/1.355

Artwork: Artist Unknown, Mexican, Colima Culture Seated Figure, c. 700 Terracotta Museum purchase made possible by a gift from Helmut Stern, 1983/1.355Artist Unknown, Mexican, Colima CultureSeated Figure, c. 700TerracottaMuseum purchase made possible by a gift from Helmut Stern, 1983/1.355

This lovely terracotta seated figure is an example of the native arts and culture celebrated by Mexican visual and musical artists. Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán transform a regional folk music into a world-class art form.

Related performance: Zafir: Musical Winds from North Africa to Andalucia

April 15, 2016

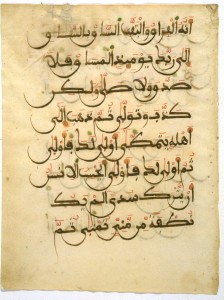

Artwork: Artist Unknown, North Africa Qur’an manuscript leaf in Maghribi script, 13th century Ink, red ochre, paper Museum Purchase, 1959/1.146

Artwork: Artist Unknown, North Africa Qur’an manuscript leaf in Maghribi script, 13th century Ink, red ochre, paper Museum Purchase, 1959/1.146

For Muslims, Arabic script, representing the language of the Qur’an, is a thing of sublime beauty. This page is written in a script called Maghribi, a variation of the earlier, angular, Kufic script. Maghribi features sweeping curves that loop across the page and was developed in North Africa and Spain. This Qur’an page combines traditions of the Middle East, Spain and North Africa as does the music of Simon Shaheen and Zafir.

Interested in more? Visit the U-M Museum of Art today.