Heroes on Speed-Dial

Editor’s note: Emerson String Quartet and Calidore String Quartet perform on October 5, 2017. In this post for UMS, Doyle Armbrust, a Chicago-based violist and member of the Spektral Quartet, interviews the Emerson Quartet’s Lawrence Dutton and the Calidore Quartet’s Ryan Meehan on the essential tradition of mentorship.

“Who was your teacher?” It’s one of those inescapable questions every professional musician is asked regularly, in addition to, “How much did your instrument cost?,” “How old were you when you started playing?,” and “Are you sure that’s going to fit in the overhead compartment?”

The more revealing query is, “Who is/was your mentor?”

A mentor is more than a pedagogue who spends an hour a week admonishing you for johnny-come-lately intonation or taser-style vibrato. He/she is that favorited contact you keep on speed dial and don’t think twice before ringing at 11 pm to post-mortem a particularly messy break-up. Figuratively, or maybe-this-actually-happened-in-real-life-to-definitely-positively-not-me.

Mentors are proxy-parents, they are sometimes cautionary tales, they are facilitators that materialize opportunities that a young musician may never have had access to, regardless of talent. This business is not a meritocracy, and while diligence and perseverance are necessities, not all worthy talents make the cut without the shepherding and generosity of a mentor.

During my undergrad years, I was stagnating with a teacher with whom, as a first-generation musician, I didn’t have the knowledge or worldview to know to leave. As luck would have it, another university snatched him up and violist luminary Donald McInnes was flown in every other week from the University of Southern California to cover the transition. There is not a shred of doubt in my mind that without his persistent and sometimes merciless provocations during lessons, the doors he opened, or the empathetic and collegial martinis at his home — just talking about life — I would not be the musician I am today.

Mentorship is essential, and as it turns out, not the easiest concept to define. I made calls to violist Lawrence Dutton of the Emerson Quartet and violinist Ryan Meehan of the Calidore Quartet, to try and tease out what makes this relationship so vital in this crazy show-business of the string quartet.

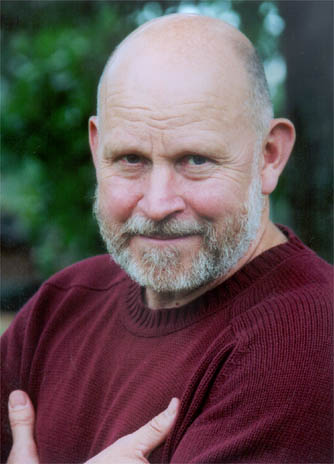

LAWRENCE DUTTON (Emerson String Quartet)

Emerson String Quartet. Photo by Lisa Mazzucco.

DA: What drew me to your concert was one word from the UMS concert blurb: “mentor.” It’s a word that has always resonated for me. What is the difference between a teacher and a mentor?

LD: I think you have to look at the context of our role in the history of string quartets. Mentoring has been a part of that process for a very long time. You could look at the Guarneri Quartet, and their mentors were, of course, the Budapest Quartet. For us, our mentors were the Juilliard Quartet, mainly. It happens because it needs to happen. It’s like luthiers — they need mentors.

A mentor can be a teacher too. It’s a combination of the two. There’s no question about that.

Probably one of the most important mentors to the Emerson Quartet was Oscar Shumsky, who Gene and Phil studied with. I did everything I could to be in his presence, like playing in a small chamber orchestra that he was conducting, or going to his recitals. This is the early 1970s, so I’m really dating myself. Shumsky was a mentor to all of us. He’s one of the primary reasons the Emerson Quartet exists! We looked up to him. We wanted to play like that.

Teaching is by definition something on a weekly basis. You can be a teacher and not a mentor. I think you can only mentor when you have people that want something very much and have the talent to try and follow in your footsteps.

DA: When I think of my mentor, I think of someone for whom the distance that exists in a teaching relationship narrows — something that becomes personal. Also, someone who created opportunities that I wouldn’t have otherwise had access to because I showed my own motivation.

LD: I would say that’s true. We’ve worked with the Calidore Quartet for several years now and they’ve had unbelievable success. That’s their doing, not ours, but we’ve done our best to help them, for instance by inviting them to play with us, as we’re doing at UMS.

DA: Is it the kind of thing where mentee texts you out of the blue to ask about something other than how to play a high ‘F’ in a Beethoven quartet?

LD: Without question. We’re happy to give our perspective and experience, because that’s what we have.

DA: In terms of taking on that more hands-on approach, is that something you feel internally compelled to do?

LD: It’s the natural order of things. These groups are showing immense promise and desire, and we want to do everything we can to push them and support their career. This is not a large pool we’re talking about — you have to have something special to be out there performing. It’s never been exactly easy (laughs). There have been plenty of people that have tried, and I know we’ve been very fortunate, but nobody really knows how you make it. If it was simple, everyone would be doing it.

DA: These opportunities don’t just materialize. You’ve gotten that person’s attention because you’re doing the work.

LD: Right. Peter Mennin [then President of Juilliard], Alice Tully, Bobby Mann [Juilliard Quartet], David Soyer [Guarneri Quartet], Felix Galimir, Walter Trampler — they were all big friends and fans, and we had that kind of relationship.

DA: When did you realize that Calidore was the kind of group we’re talking about — one you wanted to mentor?

LD: When we first heard them, we were like, “Wow, they have real personality and something to say about the music!” They were already distinguishing themselves.

DA: When it comes down to musical mentorship, how do you make room for your mentee’s own vision for a piece of music?

LD: On the level of Calidore, I find myself thinking, “I wouldn’t do it that way myself, but that is really working.” There’s no end to interpretation, otherwise there would only be one string quartet out there!

DA: Does mentorship need to be nimble, given how different the business is now from when Emerson was coming up?

LD: It’s challenging for us to even comprehend how it’s changed. I think that young quartets today have to reinvent themselves to accommodate the needs of what’s out there. Think about the fact that it wasn’t until the Guarneri Quartet in 1965 that a string quartet could make a living without a residency. Emerson came on the scene at the start of the digital age, and we got on the CD bandwagon. It’s a very short history, and we lose that perspective. There were guys in the Cleveland Orchestra that were driving cabs in the 1950s.

DA: Calidore has really rocketed into a prominent place in the chamber music world. As a mentor, is there any cautionary advice that you find yourself offering them?

LD: Well, yeah. Our career was not a skyrocket — it took a while. We only got to Europe in 1983. It was another four years before we signed with Deutsche Grammophon. It was a process, and there is no way to escape that. You’re in it for the long term.

RYAN MEEHAN (Calidore Quartet)

Calidore String Quartet. Photo by Sophie Zhai.

DA: For you, what is the delineation between a teacher and a mentor?

RM: I guess they can go hand-in-hand, and I think a teacher is almost always a mentor…at least all the music teachers I’ve had. Mentorship is about the bigger picture — goals, advice, and wisdom. They’re someone you can turn to for extra-musical help, whether that be business or personal. Teaching is the exchange of musical ideas. The Emersons have certainly been both to us. They really treat us like they do each other. There’s never the feeling that we’re the students and they’re the teachers, which is really inspiring for us. We’ve had many meals with them on the road, which have been some of my favorite memories of my life, actually. I mean, here are these people that I worshipped on recordings and on stage for so many years…and now I’m riding home with them in the car. That’s mentorship.

DA: Do you ever find yourself sending a late-night text to one of them, like, “Oh crap this thing just happened, what do I do?”

RM: We’re all very comfortable reaching out to any of them. For instance, we know we’ll always get an extremely thoughtful and thorough response from Gene to the most seemingly mundane question we might ask. Larry and Paul — actually all of them — have this insanely humorous side. Phil really considers teaching as important as performing, and he will be the one that will help us focus in on what we need to consider next in a piece.

DA: What’s an example of something non-musical that you’ve asked these guys about?

RM: Everything from the business, like, “Should we have a publicist?” Even these concerts that we’re playing with them — that was their idea and we were like, “Oh my God, I can’t believe you would do that for us!”

DA: So paint the picture for me, how did this all get started?

RM: We were at the Colburn School [in Los Angeles] and we said, we’re leaving here next year and we’re not sure what we’re doing. Five days later we got a call from the head of Stony Brook University, saying [former Emerson cellist] David Finckel had recommended us for a position studying with the Emersons and teaching the undergrads. We were dumbfounded! To be mentored by the Emersons? We had to say yes. We hadn’t met them as a group yet, but I remember that summer I went to Aspen [Music Festival] to visit, and I went backstage after their concert and said, “Hi, I’m Ryan.” They said, “Nice to meet you.” Then I said, “I’m in the Calidore Quartet and we’re looking forward to meeting you in the fall,” and then all of them immediately gave me a big hug, and it felt like we’d known each other a long time.

DA: One of the things that fascinates me about mentorship is that there is, by necessity, a generation gap. The game is different now than it was for the Emerson Quartet. How do you see them navigating those differences when they offer advice?

RM: Some things are the same. Certain etiquette, like that you should be the last people to leave the post-concert reception.

DA: Also, don’t be a jerk.

RM: Yeah. People don’t want to work with jerks. All these insider tips that are relevant to a performing ensemble today are ones they can impart to us, regardless of their generation.

DA: What does that rehearsal process look like, with the octet? There are decisions to be made and you’re rehearsing with people that have been around the block for four decades.

RM: I think what has kept them going for 40 years is that they are always thinking about the repertoire, even if rehearsal time is limited. They will find some small way to reinvent it.

DA: And you feel like you, Ryan, can die on a hill for your preferred tempo in the fourth movement of the Mendelssohn Octet, without bringing the wrath of God down upon yourself?

RM: I’m pretty vocal in our own rehearsals, but with the Emerson — I don’t know — they listen on another level. Their wealth of experience rehearsing with each other and other collaborators allows you to not have to speak too much. You just show your intent and they get it…without words.

DA: Let’s finish with something grand. What is that golden nugget piece of advice you envision handing down to a group you mentor in the future?

RM: Two things. From a musical point of view, I think you need to know how to give quick, efficient criticism and analysis. That goes hand-in-hand with the most important thing, which is that, whatever your opinion, it is secondary to getting along and treating your colleagues with respect — which the Emersons personify.

This post is written by Doyle Armbrust, a Chicago-based violist and member of the Spektral Quartet. He is a contributing writer for WQXR’s Q2 Music, Crain’s Chicago Business, Chicago Magazine, Chicago Tribune, and formerly, Time Out Chicago.

See the Emerson String Quartet and Calidore String Quartet on October 5, 2017.

Artist Interview: Takács Quartet Violinist Ed Dusinberre

On October 6, 2016, Takács Quartet volinist Ed Dusinberre was interviewed by U-M Professor of Musicology Steve Whiting at Literati Bookstore in Ann Arbor.

Takács Quartet performs the complete Beethoven Quartet Cycle during the 2016-17 at UMS, a tour in conjunction with the release of Dusinberre’s new book Beethoven for a Later Age: The Journey of a String Quartet.

Takács Quartet performs October 8-9, 2016 and January 21-22, March 25-26, 2017 in Ann Arbor.

The Perpetually Classical String Quartet

On left, Takács Quartet, and on right, Danish String Quartet. Photos by Ellen Appel and Caroline Bittencourt.

Later this fall, UMS will present performances by two renowned string quartets. In November, the upstart Danish Quartet will make their UMS debut, and the next month will see the return of the much-beloved Takács Quartet, who last performed to Ann Arbor audiences in April, 2013.

Both groups are presenting remarkably similar programs. Each will open with a Haydn quartet (both in C major, no less!), then perform quartet written in the last twenty years, and close with a Romantic quartet: Beethoven for Danish Quartet, and Dvořák for Takács. I have written previously about the way programs like these, which juxtapose older and newer string quartet compositions, demonstrate the history of the genre, namely the changes string quartet music has undergone from the Classical era to today and the recent past. At the risk of contradicting myself, I think the Danish and Takács Quartet’s programs more aptly demonstrate the way string quartet music has not changed over time. Truthfully, this kind of continuity is always present in string quartet music because the ensemble has not changed at all since Haydn wrote his first quartet in the 1760s.

Two violins, a viola, and a cello

By contrast, composers, from Beethoven to the students in the University of Michigan’s music composition department, constantly tinker with the orchestra to create different, seemingly new, sounds. Even the piano continued to evolve, mechanically speaking, throughout the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries. But, the string quartet has consisted of two violins, a viola, and a cello for over 250 years – it may be a perpetually Classical ensemble. Obviously, nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first century composers have stretched the sonic envelope of string quartet music to incredible lengths.

Black Angels by George Crumb

Devoted patrons of UMS’s Chamber Arts Series may remember the Kronos Quartet’s two performances from January 2014, when they performed, among other works, George Crumb’s Black Angels. Here, Crumb amplifies the quartet and asks its performers to yell and play various percussion instruments. This may seem like an irrevocable departure from the traditional corpus of string quartet music, but that is not the case. One of Black Angels’ more subdued movements features a heartbreaking quotation from Schubert’s String Quartet No. 14, “Death and the Maiden” – despite the experimental daring of Crumb’s sound world, Black Angels still contains a vibrant connection to the string quartet’s Classical heritage.

Arcadiana by Thomas Adés

Thomas Adés and Timo Andres, the living composers who will be performed by the Danish and Takács String Quartets, also maintain an awareness of the past in their music. Adés’ quartet Arcadiana, which appears on the Danish String Quartet’s program, features a potent allusion to one of Franz Schubert’s celebrated art songs, Auf dem wasser zu singen. Here, Adés interpolates quotations from Schubert’s song with his own musical material in a manner that contemplates what Adés observes as the most important theme of the original song’s texts: vanishing time. Accordingly, this movement of Arcadiana is strikingly characterizes by the sense of temporal unevenness; the quartet’s members do not wholly come together until the beginning of the subsequent movement. Although it has seven labeled movements, Arcadiana is composed very fluidly, and typically performed so that each section into the next without interruption. Similarly, though “Auf dem wasser zu singen” is the only part of Arcadiana to make an explicit reference to nineteenth century music, the rest of the work clearly expresses a kind of refracted anachronism that draws heavily on traditional compositional precedents. Much of the work is typified by active gestures and fleeting melodic and harmonic ideas, except for the penultimate movement, “O Albion”, which is a stunningly simple and beautiful statement in counterpoint.

An interview with Timo Andres

Timo Andres’ Strong Language, which will be played in between Haydn and Beethoven on the Takács Quartet’s December program, is more of a mystery because it has not yet received its premiere performance. However, Andres discusses the work at length on his website, describing it as an exercise in musical economy: “Strong Language has three movements and exactly three musical ideas.” Andres is also a renowned pianist, who frequently performs standard repertoire alongside his own compositions and those of other living composers. Thus, it seems likely this new work for string quartet will possess some kind of grounding in Classical music’s tradition. Certainly, this is the case in Andres’ last quartet, Early to Rise (2013), which, like Arcadiana, makes allusions to nineteenth century German art song (though, Andres’ work references Schumann, not Schubert). Per Andres’ description, Strong Language indeed seems to embrace numerous traditional compositional techniques, though its final movement features atypical instrumental sounds, such as scrapes and knocking.

Nevertheless, it is likely Strong Language, just like Arcadiana, will provide further evidence that the string quartet, as a genre and ensemble, is perpetually Classical. Even the purported noise elements in Strong Language’s closing movement are nothing new – George Crumb’s aforementioned Black Angels features similar effects and is forty-five years old.

Of course, the consistency in the string quartet and its repertoire I point out here does not represent a weakness for the ensemble, but, rather, an incredible strength. To support the expression of so many different composers over 250 years of Western musical history with the same instrumentation tells us a great deal about the enormous value of the string quartet as a medium. Be sure to consider the enduring strength of this musical tradition when it is on full display in the surely masterful performances the Danish String Quartet and Takács Quartet will share with UMS audiences in November and December.

The Danish String Quartet performs on November 6, 2015, and the Takács String Quartet returns on December 6, 2015.

Interested in more? Garrett Schumann is a regular contributor to UMS Lobby.

Perspectives on Melody in Dvorak, Tchaikovsky, and Vasks

Artemis Quartet perform in Ann Arbor on April 19, 2015. Photo by Molina Visuals.

The Artemis Quartet’s program features two stalwarts of their usual repertoire alongside a recent work by one of Europe’s leading contemporary string composers, Peteris Vasks. Born, educated, and based in Latvia, Vasks began his musical life as a bassist before transitioning to composition in the 1970s. His experiences as a string player are likely responsible for the plentitude of pieces for string ensembles among his output. More importantly, his familiarity with the sound of string instruments equips him well to write highly evocative, highly expressive string music.

A strong melodic focus

While it may seem that Vasks, Dvořák, Tchaikovsky have little in common beyond the fact they are all European composers, this is not wholly the case. All three create music with a strong melodic focus that gravitates toward a clear lyrical style. Of course, Vasks enjoys and employs more freedom than Dvořák or Tchaikovsky, whose aesthetic choices were effectively dictated by a syntax of musical ideas shared among essentially all contemporaneous European composers. Indeed, melody is a de rigeur element of nineteenth century music, and Tchaikovsky is regarded as one of the best melodists in history. The Quartet No. 1 in D major (1871), part of the Artemis Quartet’s April 2015 program, certainly lives up to his reputation, although its tunes may not be as famous as those featured in Tchaikovsky’s ballets.

More interesting are the melodic experiments present in Dvořák’s Quartet in F Major, “American” (1893), which contains the pentatonic scale in abundance. The presence of this five-note scale, which also appears prominently in Dvořák’s Symphony No. 9, “From The New World” (1895), may have garnered the quartet’s nickname, as the pentatonic melodies suggest non-white American folk music. Dvořák wrote fondly of African-American music, which he heard while living in the United States, and it’s reasonable that he may have tried to refer to this tradition in the pieces he composed during this period.

Thinking beyond the movement

Although Vasks values melody in a very traditional sense, he treats it more dynamically than Dvořák or Tchaikovsky. As you will hear, Vasks thinks beyond the movement of one note to another; he develops color, register, and texture as well. Vasks’ string orchestra work Musica Dolorosa (1983) demonstrates this quality very clearly, moving from a mournful, romantic melody to an intense, aleatoric swarm of dissonance. Although there is no existing recording of Vasks’ String Quartet No. 5 (2008), his other quartets possess these same characteristics, despite the more limited instrumentation. Thus, it seems fair to expect the same in his more recent work.

In program notes written for his publisher, Vasks describes elements of his dramatic String Quartet No. 5 as, “atmospheric”, “a cry of utter desperation”, and, “a forgiving, loving look at a world tortured by grief and contradictions.” Structurally speaking, this quartet marks a departure for Vasks. String Quartet No. 5 has only two movements – being present and so far…yet so near – while the previous four all have at least three, with his String Quartet No. 4 (199) sporting five wildly contrasting movements. It will be interesting to see whether the seemingly condensed form of the String Quartet No. 5 manifests a unified and cohesive piece, or if the two titled movements simply represent two adjacent, yet individual, regions of diverse, free, and expressive musical ideas.

Interested in more? Explore our listening guide to the evolution of the string quartet.

Backstage with Emerson String Quartet

The Emerson String Quartet performance on September 27, 2014 featured a world premiere of a new work by composer Lowell Liebermann. Here is the composer and the quartet backstage with U-M emerita history of art professor Ilene Forsyth, whose remarkable gift to UMS endows a Chamber Arts Series concert annually.

Did you attend the performance? Don’t forget to tell us what you thought.

Artist Interview: Cellist Paul Watkins, Emerson String Quartet

Photo: Emerson String Quartet. Photo by Lisa Marie Mazzucco.

The Emerson String Quartet returns to Ann Arbor on October 5, 2017 to perform with Calidore String Quartet.

Cellist Paul Watkins joined the quartet in May 2013. UMS Lobby contributor and composer Garrett Schumann chatted with Paul about what it’s like to join the quartet, his British sense of humor, and his role as artistic director at the Great Lakes Chamber Music Festival.

Garrett: You joined Emerson Quartet during the 2013-2014 season. We often hear about the demands of precision and cohesion that string quartets require. What has the process of assimilating you, a new voice, into the Emerson Quartet been like?

Paul: Well, you know, it has its challenges because I’m coming into a group of guys that’s worked together for the last 37 years. And in fact, in the case of Phil [Setzer, violin] and Gene [Drucker, violin], they’ve known each other and each other’s playing since they were college students, going back more than forty years. There’s a degree of responsiveness that they have to each other which I have to catch up with. But luckily when we played together for the first time, I think we all felt a very natural and quick connection in our styles of playing. Good basics to work from. But we’ve had to rehearse a lot over the last year, probably more than the quartet was used to.

Garrett: I saw that the press release announcing your joining the group noted your vibrant sense of humor.

Paul: Ah! Did it! Good.

Garrett: I’m wondering what you have to say about that. Do you think that part of your personality had any specific implications in your first season with the group, or is there any particularly funny anecdote from your first season that would match the expectations that were built by that press release?

Paul: [Laughs] That’s very interesting. I think all three of the guys in the quartet apart from myself have got very highly developed senses of humor. So you know, we fool around in rehearsals. Maybe the subject of a lot of our jokes in our first year has been the difference between British English and American English. One thing that comes to mind, too, is just before I gave my first official concert with the quartet, they gave me a little spoof “welcome” pack, which had various characteristics of the individuals in the quartet, slightly exaggerated. It’s been quite funny for me to discover that pretty much all of the things that were there are absolutely true. [Laughs]

Behind the scenes with Emerson String Quartet:

Garrett: [Laughs] So, the program that you’ll be performing at UMS has Beethoven and Shostakovich and also has the new piece by Liebermann that was a UMS co-commission. Could you talk about the process of creating a program with the quartet? What are the things that you discussed and thought about when you designed it?

Paul: I think for a lot of quartets that have been together for a long time, each individual member of the quartet tends to have a different role. And in our quartet, Philip has a lot of responsibility for programming, it’s something that he loves doing. He really relishes the prospect of putting together different pieces and relating composers to each other within a program or within a concert series. While he does the lion’s share of that work, we other three have a lot of input as far as that’s concerned.

Since I joined the quartet, I’ve also shared the repertoire that I’m particularly interested in. For me, Beethoven string quartets are still really the towering achievement in string quartet literature. Nothing’s equaled or surpassed them since he wrote them. My top priority personally was to explore as many Beethoven string quartets as soon as possible with the Emerson.

Garrett: How do you think Ann Arbor audiences will feel about this program with its mixture of very traditional Beethoven and Shostakovich and also this new piece, which none of us will have heard of course?

Paul: Exactly. We haven’t heard it yet! It’s nearly ready. As with a lot of composers, they write very close to deadline, but we’re expecting it to arrive really any day now, so that we could start working on it over the summer. Lowell Liebermann is a very lyrical composer…I’m not sure! I’m nervous to commit to anything in particular about the piece because I’m not sure what kind of piece he is going to write! In a way that’s a kind of surprise.

Garrett: I’m a composer myself so I understand your hesitance to commit anything because who knows! Well, your other big news in addition to the Emerson String Quartet is your new position with the Great Lakes Chamber Music Festival.

Paul: Indeed! I’m very excited about that.

Garrett: What attracted you to that position?

Paul: Actually, in a couple of hours, I’ll go to Detroit because it’ll be the opening of the 2014 festival. The Great Lakes Festival has a very strong personal connection for me because Detroit is the home town of my late mother-in-law Ruth Laredo, who was a very distinguished American pianist and a wonderful lady and a powerful influence on me and many other people.

Her sister still lives there, so they’re a great family connection. She was also a great friend and artistic companion to James Tocco when he founded the festival twenty years ago with his brother.

There’s also a wonderful team of people working for that festival, and it seems that it has a very unique and welcoming atmosphere. This all made me think that working for the festival would be a great challenge but also a great sort of privilege. It’s the first time that I’ve been an artistic director of a major chamber music festival, so I’m very excited to see that work put into practice.

Garrett: What are you thinking about programming, what’s coming up for the festival now that you’re starting your position in August?

As far as programming is concerned, I think what James Tocco has done over the last twenty is very, very good. I want to take that all and develop it. Because I have a British and European background, I want to encourage much more collaboration and cross-pollination between American and European artists. In 2015, we’re going to call it “Coming to America,” which is essentially a kind of short hand for my personal experience of moving to America as a European musician, but also for American composers who have been influenced by Europe, and vice versa.

The opening concerts of the 2015 festival are also going to feature the Emerson String Quartet. That’s an opportunity for me to bring my new friends at the quartet to meet my new friends in Detroit and get things off to a really exciting start.

Garrett: That sounds wonderful. Michigan has a lot of great musicians, composers, and a lot of excited people to hear it. We can’t wait to experience the festival next year.

The Emerson String Quartet performs in Ann Arbor on October 5, 2017.

Updated 7/10/17

The Audio-Biography Of The String Quartet

Photo: Elias String Quartet. Photo by Benjamin Ealovega.

The program the Elias String Quartet will share in its UMS debut on March 18 is like a sonic timeline of Classical Music’s most important genres, the string quartet. The three works the group will perform – Beethoven’s String Quartet in E minor, op. 59, no. 2., Debussy’s String Quartet, and György Kurtág’s Officium Breve – fit together like a veritable textbook on how the string quartet was established, codified, and subsequently transformed from the nineteenth century through the 1980s. It is extremely unusual, and very exciting, to have so succinct and comprehensive a portrayal of music history available on a single concert program.

Of course, this history begins with Beethoven, whose “middle” period works, such as the op. 59 quartets, represent his great turning point from an extremely skilled and gifted Classical composer, to the daring and freely minded Romantic hero music lovers glorify today. Beethoven’s metamorphosis was extremely precipitous to the history of Classical Music in the nineteenth century, and the String Quartet in E Minor, op. 59, no. 2 is certainly part of this legacy. This specific work contains numerous instances of Beethoven’s personality infecting the music’s form and affect; for example, in a likely allusion to the impolite Russian count who commissioned the set this quartet is part of, the work’s scherzo movement features an indelicately harmonized melody that was popular in Russia.

In light of the nearly invincible grip Beethoven’s influence had on nineteenth century composers, it is reasonable to think Debussy considered the German’s quartets when he penned his own in 1893. With that said, Debussy’s String Quartet, like his other music, breaks Beethoven’s mold in a number of ways, most obviously in its exploitation of instrumental color (listen for the prominent pizzicato passages in the second movement!). However, we should not interpret Debussy’s innovations as dismissive – rather, he makes vital changes to a genre that was over a century old at the time, and the musical expressions he explores are echoed by other composers in the early twentieth century, such as Maurice Ravel and Leoš Janáček, among others.

If Debussy’s String Quartet upholds through modification the traditional character of the string quartet as a stand-alone art form, a work like Kurtág’s Officium Breve shows how composers at the end of the twentieth century sought to more totally liberate this ensemble from its longstanding heritage. Officium Breve is starkly different from the other two works on the program – it is made up of fifteen short movements and is populated by constantly-shifting sounds and textures that represent extremely terse expressions on the part of the composer. Ranging from violent explosions of sound to tender periods of quietude, this work is enormously vibrant and deeply captivating.

Despite the fact Officium Breve bears little salient resemblance to the heart of its genre’s tradition, Kurtág’s work echoes the philosophy conveyed in the quartets of Beethoven and Debussy: existing forms may, and should, be altered in the name of artistic expression and ego. Placing living composers in a linear context with widely performed and recognized historical composers helps us, as listeners, observe how recently written music relates to the traditions with which we are more familiar. Unlike ensembles that predominantly program music from the nineteenth or eighteenth centuries, the Elias String Quartet is inviting its audience to share in these connections and is giving us a chance to see how a hugely important genre in Classical Music has grown over its centuries-long life.

Interested in more? Read more Garrett Schumann’s writing on UMS Lobby.

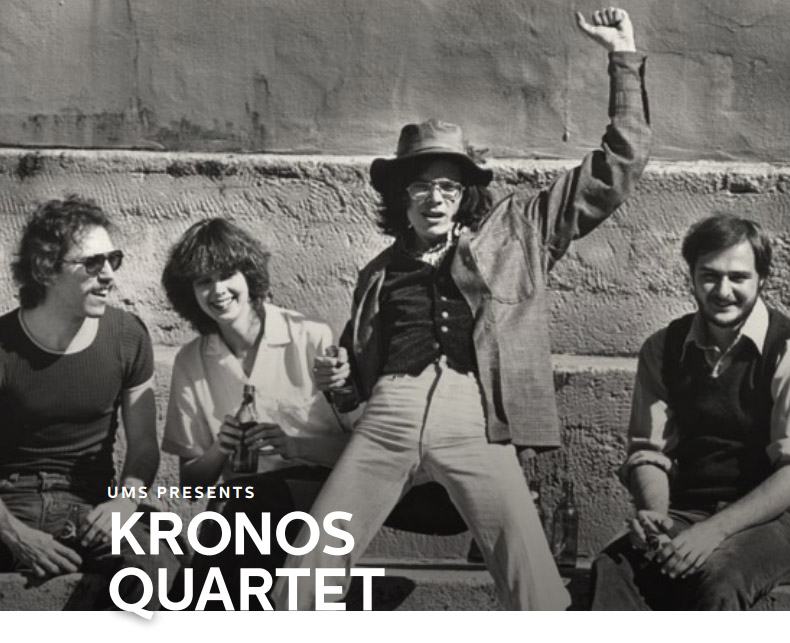

Archival Photo: Kronos Quartet

Photo: Kronos Quartet. Courtesy of the artist.

We love this archival image of the Kronos Quartet. About 40 years ago, they started out as classical music’s original renegades and continue that cause to this very day. Kronos Quartet performs two different programs on January 17-18, 2014.

Our interview with members of Brooklyn Rider

Brooklyn Rider’s Johnny Gandelsman, Nicholas Chords, Colin Jacobsen, and Eric Jacobsen talk visiting Ann Arbor and explain why they’re excited about working with banjo star Béla Fleck.

They perform at Rackham Auditorium on November 24, 2013.

Behind the Scenes with Takács Quartet

During the 2016-17 season, the Takács Quartet performs the complete cycle in only four venues worldwide, coinciding with the release of a book by Takács first violinist Edward Dusinberre, Beethoven for a Later Age: The Journey of a String Quartet. The book explores the inner life of a string quartet, melding music history and memoir as it explores the circumstances surrounding the composition of Beethoven’s quartets.

In 2013, we interviewed Dusinberre about putting together a performance program:

Last updated 4/29/2016.

Tracing the String Quartet

Photo: Takács Quartet performs. Photo courtesy of Frank Stewart /Savannah Music Festival via npr.org.

Like the Mass, Opera and the Symphony, music for String Quartet is one of the most enduring genres in Classical Music. Since the genre’s emergence at the end of the eighteenth century to the present, generation after generation of composers have found this grouping of a cello, viola and two violins, inexhaustibly fascinating. Although there are a few notable exceptions, nearly every composer from Haydn to the present day has used this genre as a place for growth, experimentation and, above all, individual expression. Armed with its deceptively simple instrumentation, the String Quartet is capable of achieving an enormous range of textures, colors and moods, a generous sampling of which will be on tap at the April 12 performance by the world-renowned Takács Quartet.

The evening’s program begins with a representative work by the father of the String Quartet, Joseph Haydn, who, arguably, invented the genre out of necessity while working at the country estate of Baron Carl von Joseph Edler von Fürnberg. The ‘Sunrise’ Quartet displays the foundational form for String Quartets in the Classical Period, which was borrowed from symphonic music. The first and last movements are fast, and intervening are a slow second movement and a minuet, or, sometimes, a scherzo, which feature lighter fast music than the outer movements. Beethoven, who studied with Haydn, continued this formalism in his charming early quartets, but by they time we get to the Quartet no. 14 in c-sharp Minor, we encounter a work that is much longer and more formally diverse than its predecessors in the genre.

Dating from the final period in Beethoven’s life, the Quartet no. 14 is a leviathan and explosive gesture of Romanticism. Although this might seem hard to believe to a contemporary audience, most of Beethoven’s late works, including this quartet, were considered wildly and undesirably avant-garde. The Quartet no. 14 breaks the rules by possessing an unprecedented structural circularity, which means the audience should consider the piece as one large musical idea, instead of a series of smaller, separate gestures grouped together under one title. This continuity is built into the performance of the Quartet no. 14, because its seven movements are played without breaks between them.

Benjamin Britten

If Beethoven’s Quartet no. 14 represents the genre’s ability to portray a composer’s idiosyncrasy, and Haydn’s ‘Sunrise’ Quartet represents String Quartet music’s formal origins, then Benjamin Britten’s String Quartet no. 3 in G major, proffers one example of how later composers balanced these seminal elements. The work uses a broad range of textures and colors, which harkens to the diverse material of the Beethoven, though String Quartet no. 3’s five movements are decidedly unrelated, which is more in tune with Haydn’s Classical Period quartets. Britten died two weeks before the String Quartet no. 3 was premiered, but the piece is not a personal requiem, despite its many haunting and beautiful passages. Nevertheless, the work is a culminating example of Britten’s music, not to mention more modern composers’ contributions to the long line of works written for String Quartet.

Garrett Schumann is a regular contributor to UMS Lobby. Read his other commentary.