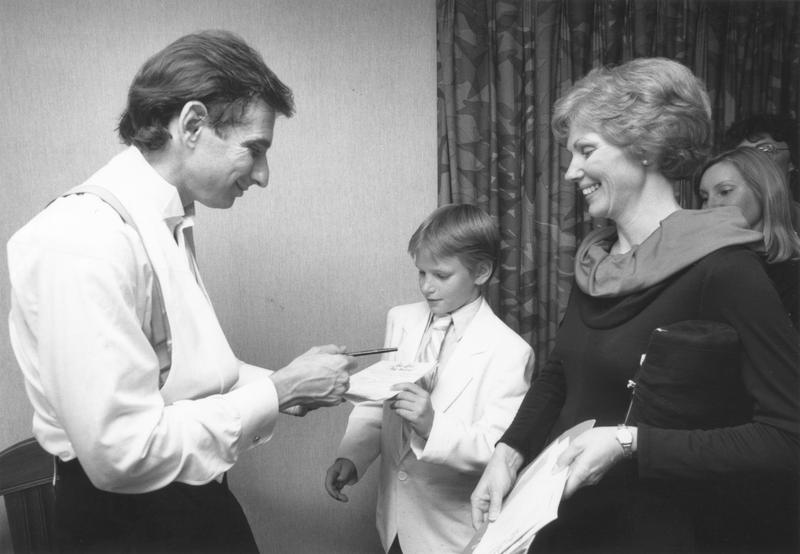

Michael Tilson Thomas at 1988 UMS May Festival

We’re getting ready for another visit from San Francisco Symphony on November 13 and 14, 2014. This visit celebrates the 70th birthday of music director Michael Tilson Thomas, and we wanted to share two archival photos from another performance featuring conductor Michael Tilson Thomas, the 1988 UMS May Festival.

In this photo, the Pittsburgh Symphony performs at 1988 May Festival with Michael Tilson Thomas conducting.

Michael Tilson Thomas signs autographs backstage in Hill Auditorium.

To learn more about the May Festival’s one-hundred year history, watch “A Space for Music, A Seat for Everyone,” our feature documentary about Hill Auditorium.

Interested in more from our archives? Check out our digital archives at umsrewind.org.

Student Spotlight: Embedded with San Francisco Symphony

Editor’s note: This summer, UMS launched a new 21st Century Artist Internships program. Four students interned for a minimum of five weeks with a dance, theater, or music ensemble part of our 2014-2015 season. Libby Seidner is one of these students. She spent five weeks with the San Francisco Symphony.

Below, Libby shares her travel stories with the orchestra in advance of their return two Ann Arbor on November 13 and November 14, 2014. They’ll perform two different programs.

Photos: On left, a photo from my first time on the Golden Gate Bridge. Walking across the Bay to Sausalito was one of my favorite SF activities. On right, view from Baker Beach. All photos by Libby Seidner.

During my first week at the San Francisco Symphony artistic planning coordinator Jim Utz asked me, “You do realize that you’ve come to the busiest symphony orchestra?” I nodded and smiled, but I had no idea what I was in for. At 52 weeks, the SFS has one of the longest seasons of any symphony orchestra. Those 52 weeks are packed with recording projects, album releases, domestic and world tours, concerts for families, as well as fantastic series concerts at their home, Davies Symphony Hall, right in the heart of San Francisco. The Symphony employs 107 musicians and 140 staff.

Being a fly on the wall of this large non-profit organization was an unbelievable learning experience. As part of my internship, I worked on artist interviews, collected behind-the-scenes photos, managed education events, the Britten Festival, an album release, and more. For college students, finding opportunities to work with a symphony orchestra while in season is nearly impossible. The UMS 21st Century Artist Internship program provided me with the professional and education experience of a lifetime.

Photos: On left, Davies Symphony Hall at night from street level. The building was designed specifically to look open and inviting from the outside. On right, a view of city hall from the third floor balcony of Davies. It was amazing to see the entire city covered in rainbow to celebrate pride week.

One of my favorite components of the internship was interviewing SFS musicians. I got to know Symphony personnel while discussing repertoire, the upcoming tour, and the historic relationship between UMS and the SFS. Over the course of the interviews, I found myself feeling closer to the orchestra and more connected to the music they were making.

While attending concerts and listening in on rehearsals I had “friends” to listen for. For example, I got to know principal clarinetist Carey Bell, who studied undergraduate clarinet performance and composition at the University of Michigan School of Music, Theatre, and Dance. We bonded over shared experiences of Zingerman’s Deli, the practice rooms of the SMTD and the amazing Ann Arbor student community.

The experience of building these relationships taught me the importance of reciprocity between audience and artist. As an audience member, I am more engaged when I have context. Building relationships with orchestra members reduced the distance I often felt as a listener. I hope to build this bridge for UMS audiences.

Photos: On left, SFS principal clarinetist Carey Bell and me after our video interview. Carey received his bachelor’s degree at the University of Michigan, studying clarinet performance and composition. On right, Carey Bell coaches a chamber group of local amateur musicians during the Community of Music Makers event.

UMS and the SFS are organizations that work well together because of their shared commitment to access and innovation. Both are looking to provide the best arts experience to as many different people as possible. While I was at the SFS, development of a new series called “Soundbox” was underway. This future concert series will take place in a smaller hall and be directed towards a younger and more diverse audience. The concerts will feature new music and have a host who’ll share insights into the performance.

Similarly, UMS encourages college students and community members to get involved in the arts through programs like U-M classes about the performances, educational electronic media, half-price student tickets, and internship opportunities. These organizations inspire me to think broadly about arts institutions as community organizers. What is the role and responsibility of an arts organization in the community?

One such inspiring SFS initiative that engages reciprocally with the community is the Community of Music Makers program, led by Lolly Lewis of the education department. These events brings local amateur musicians into Davies Symphony Hall to be coached by Symphony musicians and conductors. At the end of a day of hard work and rehearsals, the local musicians have a chance to perform on the Davies Symphony Hall stage.

The performance is the most beautiful part of the event.The musicians perform for each other and a few close friends and family members. The intimacy of the small performance makes the giant hall seem less intimidating and foreign. The idea is to open up the private stage into a public place for genuine civic activity. Not only do the amateur musicians tend to become more engaged audience members and supporters of the SFS, but the Symphony musicians have had a rare chance to meet their audience. The Community of Music Makers program serves as a superlative model for community arts engagement.

Photos: On left, a local amateur string trio coached by SFS cellist Barbara Bogatin during the Community of Music Makers event. On right, after several hours of coaching, the ensembles perform for one another on the stage of Davies Symphony Hall.

In addition to connecting with the Bay Area community, the Symphony reaches a half a million listeners every year through domestic and world tours, weekly radio broadcasts, and media sales. My internship lined up with the release of the SFS’s recording of West Side Story. This live recording is the first-ever complete concert performance of Leonard Bernstein’s original score.

Having the chance to see what’s involved in a major recording release was an incredible experience. Although many of the media meetings that I sat in on were over my head, the energy surrounding the album release in those weeks was palpable—holding the CDs before they became publically available was thrilling.

The release culminated with a party at the top floor of Twitter headquarters on Market Street. Here, I got to see Michael Tilson Thomas and the stars of the recording up close, as well as hear performances of “Maria” by Cheyenne Jackson (Tony) and “I Feel Pretty” by Alexandra Silber (Maria). #IFeelPretty #SFSWSS #TonightTonight!

Photos: On left, Cheyenne Jackson and Michael Tilson Thomas at the West Side Story album release party in the Twitter building. Mr. Jackson sings the role of Tony on the album. On right, Alexandra Silber performs “I Feel Pretty” at the West Side Story album release party in the Twitter building. Ms. Silber sings the role of Maria on the album.

My internship also lined up with an SFS series concert featuring international violin soloist Gil Shaham (who’ll also perform in Ann Arbor in November!). Mr. Shaham and the SFS have had over 26 performance engagements together, and the violinist also has strong ties to Ann Arbor, having commissioned and premiered several pieces by U- M composition faculty, including William Bolcom and Bright Sheng.

I was very excited to hear Gil Shaham and the SFS play but never imagined that I would meet him. When I proposed the idea of video interviewing Gil Shaham about Ann Arbor and the upcoming tour, I expected the answer “no.” However, I was surprised and delighted that Mr. Shaham was happy to talk to me!

Meeting Gil Shaham was one of the major highlights of my internship. His extreme musical talent is matched only by his warm personality and approachability. We shared stories of Ann Arbor, performing in Hill Auditorium, the San Francisco Symphony, and UMS. Needless to say, the Ann Arbor music community is very much looking forward to the reunion and return of these artists to the stage of Hill Auditorium this November!

Photos: On left and right, the Symphony rehearses Prokofiev’s Violin Concerto No. 2 with Gil Shaham.

The Symphony’s support in this project was a testament to the character of everyone involved at the SFS. Although I was an intern, not very high up on the food chain, no one treated me that way. Whenever I had an idea or request, I was provided with the resources. I am so grateful to have had the chance to work at such a giving organization.

Photo: Several members of the Operations Department celebrate General Manager John Kieser’s birthday. From left to right: Andrea Drummond, John Kieser, Jeannette Wong, Joyce Wessling, Casey Daliyo, Nicole Zucca, and Jessica Huntsman.

Excellence and innovation were terms that I heard frequently around the Symphony office, referring to the talent on stage and off. A world-class orchestra, elite administration, and excellent people, make the San Francisco Symphony so incredibly successful as an international arts leader, a community organizer, and an orchestra. I had an amazing summer working with the best symphony orchestra in the best city. As the song goes, “I left my heart in San Francisco.”

Interested in more? Check out San Francisco Symphony through our archives.

Renegade Reflections – Guest Blog by Leslie Stainton

Editor’s Note: Lobby contributor Leslie Stainton will guest blog the San Francisco Symphony American Mavericks festival throughout this weekend. Read her notes on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday.

What’s next for Jeremy Denk? Definitely not Disneyland. After Sunday’s rollicking performance of Lukas Foss’s “Echoi”—a pseudo-string quartet that lent new meaning to the word “string”—the pianist was heading to Carnegie Hall, where the SF Symphony will reconfigure its Mavericks series for New York audiences this week. Denk said he and his fellow performers are bracing for a different kind of reception from the one they got here. I asked him after Sunday’s performance how he’d liked his week in A2:

Sunday’s concert drove home for me some of what the Mavericks series—and the Renegade series overall—have achieved:

- An expanded idea of what constitutes a musical instrument (Foss’s “Echoi” culminated in a dramatic thrashing of a dusty garbage-can lid) and the sounds that musical instruments—including the human voice—are capable of making. Piccolo as siren, bass fiddle as drumhead, soprano as piccolo. Our isle is indeed full of strange noises.

- A humbling appreciation of how conventional our musical tastes tend to be. Bach on the radio this weekend just didn’t do it for me. I’m sure I’ll swing back, but after the likes of David del Tredici, the Baroque seems a tad tame just now.

- Magnificent resonances—not just within the Mavericks series but within Renegade as a whole. Echoes of “Einstein on the Beach” throughout, most recently in yesterday’s vocal works by Meredith Monk and Morton Subotnick. Hints of the Hagen Quartet’s furious playing in yesterday’s Foss quartet, traces of the Tallis Scholars in Monk’s unorthodox blending of voices, and so on …

- The urgency of live performance—especially now, when we filter so much of our human experience through screens.

- The urgency of a vibrant cultural life—and the need to support it. (Thank you again, Maxine and Stuart Frankel.) Yesterday’s paper brought news of dwindling arts support in Europe. Artists and arts organizations are being asked to justify their existence by demonstrating economic impact. It’s a killer for small, weird stuff like the kind of music we’ve just spent four days absorbing, or something as mind-opening as Robert Lepage’s “Andersen Project.” And yet how vital the enterprise is to being human. I was reminded of it at last week’s American Orchestra Summit here in A2, when two bright and gifted teenagers talked about what music—hearing it, playing it, studying it—meant to their existence. This stuff saves lives, don’t kid yourself.

- The many ways that unconventional work stretches performers and audiences alike. A friend remarked to me yesterday that he’d never much liked contemporary music before, but the Mavericks series had changed him. I feel the same way. This has been a mind-expanding experience—a giant “Maverick martini,” without the hangover.

I asked a few people who’ve been closely involved with the Renegade series since its inception to reflect on the past two months—high points, low points, and everything in between:

“Stretch. That’s the word that’s come to my mind most often over the past 10 weeks, and especially in the past four days with the SFS. I love this feeling that, even when I think I’ve seen it all, something like the Renegade series stretches me in new and exciting ways as an audience member. I’ve felt myself grow, becoming more willing to tackle the ambiguous or unfamiliar, and to give myself over to these experiences in the moment. The big gift of Renegade for me is that it seems to have opened up a much more public conversation about what UMS is putting on the stage, and audiences are describing their experiences in more nuanced and complex ways (we’ve made good progress away from the like/dislike dichotomy!). With Renegade, we set upon a journey of intentional watching/listening/experiencing. It’s been interesting to see how some of us really embrace that idea, and it begins to change in new and exciting ways how we experience performance. And now that the journey has come to an end, I’m aware of how exhausting it can be to be stretched, but I’m looking forward to using this greater capacity that I’ve developed within myself and applying it to next season.”—Jim Leija, Education Director, UMS

“I was constantly on my toes. I was surprised and never knew what to expect. Just as I would sit back and say, ‘Well, yes, yes. this is going to be something I’m familiar with,’ WHAAM, something would happen to engage me/entrance me/surprise me. I am exhausted by LISTENING to all that fabulous music.”—Prue Rosenthal, Former Chair, UMS Board of Directors

“I will admit that I approached the series with some trepidation, not being sure if audiences would be receptive to the works programmed on the series. It was such a thrill on Thursday night to see the instantaneous positive response – a response that mostly continued throughout the four concerts. Not everybody liked everything, nor would I expect them to, and in all honesty, I wish more of the dissenters had posted on the Lobby also. But there was something really powerful about hearing so much modern music in a concentrated timeframe and realizing that it isn’t as scary as it looks on paper. I wish we could clone MTT, who is able to bring meaning to the pieces with just a few words about each composer. One commenter on the Lobby website was dismayed by this music being ‘ghettoized’ (my word, not the commenter’s) in one program, and thought it would be better to have it interspersed with other, more traditional works. But I’m not convinced of that. Henry Cowell in the context of Tchaikovsky or Brahms will have a decidedly different impact than when heard in the context of Varese, Ruggles, or Harrison. These concerts were a great way to introduce the idea that modern music IS accessible and enjoyable, not that it’s medicine that you need to take in order to get the Beethoven. On the whole, I was so proud of our community for embracing this festival wholeheartedly. It’s fine not to like everything – heck, I run fleeing whenever Brahms is on the program! – but the willingness to embrace the unknown was just another example of why I live in Ann Arbor.”—Sara Billmann, Director of Marketing & Communications, UMS

“What made me happiest about Mavericks and Renegades was not always knowing in advance what was going to ‘work.’ Concert programming so often presents us with an unbroken string of success stories, and that was definitely not the case with the American Mavericks’ works, several of which were ‘hot off the press.’ I was thrilled by Varèse, Cowell, Bates (of whom I’d never heard), and Foss . . . and bored by Monk and Subotnick (I don’t handle rhythmic monotony well). What was exciting in most cases, though, was not knowing what to expect. This has been an ear-freshening semester, and UMS has my sincere thanks for that.”—Steven M. Whiting, Professor, UM School of Music, Theatre and Dance; Guest Lecturer, UMS Night School

“I’ll never forget the bookends of the series — Einstein and the San Francisco American Mavericks concerts. Both were transformative to my perspective on culture in American life—watching Einstein be remounted and come into being on campus was phenomenal and gave me a rich appreciation of the work; the symphonic realization of Ives’s Concord Piano Sonata clarified my vision of the work and is still ringing in my ears. Over the course of the Renegades Series, I’ve come to see the figure of the Maverick in American culture as less of an outlaw and more of a driver of innovation, really a thought leader. That Mavericks have become a tradition in America and across the globe gives me hope that we can solve the problems that we face as a nation and world citizens. I’m certain that the Renegade Series has inspired the whole campus, faculty and students alike. Another takeaway has been the incredible value of attending shows that I don’t usually attend — for me dance and theater. UMS provides us with a rich variety of cultural experiences, and I think we as audience members need to challenge ourselves more often to attend things outside of our experience. Certainly the students in my Mavericks and Renegades class have discovered the value of expanding their cultural diet, we’ve all grown as a result.”—Mark Clague, Associate Professor of Music; Instructor, UMS Night School

Unpacking the sets for John Cage’s Song Books

Unpacking the sets for John Cage’s Song Books on Friday, March 23 at Hill Auditorium. Join the discussion and read audience reactions here.

From the UMS Video Booth

Our video booth had a long run over the weekend at the San Francisco Symphony American Mavericks festival.

The Lives of Men – Guest Blog by Leslie Stainton

Photos from the UMS Archive. 1. L-R: Gordon Mumma with visiting composer Morton Feldman, ONCE Festival (1964), Ann Arbor. (Photo: Donald Scavarda) 2. Morton Feldman in Ann Arbor, ONCE Festival (1964). (Photo: Makepeace Tsao, courtesy of the Tsao Family)

Editor’s Note: Lobby contributor Leslie Stainton will guest blog the San Francisco Symphony American Mavericks festival throughout this weekend. Read her notes on Friday and Saturday.

Biography kept popping up. From Saturday’s pre-concert presentation on Charles Ives and his Concord Sonata, to the intros to each of the evening’s pieces, to the final, riveting and mercurial Concord Symphony, character and personality held center-stage throughout last night’s program. I’ve devoted huge parts of my life to writing and reading biography, so I generally don’t need convincing, but I found myself wondering at times last night whether it makes a difference to know, for example, that Carl Ruggles hated Brahms and destroyed much of his own work, or that Morton Feldman was a friend of Mark Rothko. In the end, I think it does.

Before each of the three pieces on Saturday’s program, Michael Tilson Thomas spoke briefly, and fondly, about its composer. Of the difficult and “craggy” Carl Ruggles, whose “Sun-treader” (1931) opened the evening, MTT said, “He spent most of his life pent-up in a small, one-room schoolhouse in Vermont with a piano a pot-bellied stove, and his adoring wife.” On weekends, Ruggles was visited by the likes of Thomas Hart Benton (who used the composer as a model for Ahab in his illustrated “Moby Dick”). Ruggles produced a slender oeuvre—just a dozen or so works—and they’re filled with defiance, rage, deep sorrow, and an aching passion, MTT said. “You instantly know it’s a statement by Carl Ruggles. So get ready.”

And he was right. With its huge and sober sounds, beautiful and raging all at once, “Sun-treader” seemed to me a palpable cry. I kept thinking of Icarus, striding toward the sun in his doomed chariot. And of Ruggles himself—a man who denounced the mainstream, an outlier unafraid of gods.

If Ruggles was a small man who wrote big, MTT said by way of introduction to the second work on the program, Morton Feldman was a big man who wrote delicate music. And then MTT launched into a brief imitation of Feldman—put on your best Brooklyn accent, and you’ve got it. “Dis work is de classiest ting Ay eva wrote,” Feldman (in MTT’s version) might have said about his “Piano and Orchestra” (1931), which MTT described as a cross between Webern and Duke Ellington. Elegant it was, as subtle and moving as a Rothko canvas (to which both MTT and the program notes likened Feldman’s work—MTT noting that “time” was Feldman’s “canvas”).

At one point during this languid piece, I felt as if I were hearing a deeply sophisticated “Peter and the Wolf,” so magically did the work illuminate each instrument in the orchestra, allowing us to focus on color and tone rather than the usual culprits, melody and rhythm. (Is it stretching things to suggest this functioned at least in part as a “biography” of an orchestra?)

Biography returned full-force in Charles Ives’s “Concord Symphony,” the last work on Saturday’s program, with its four sections devoted to four men who inhabited the legendary town where the American Revolution erupted—Emerson, Hawthorne, Alcott, Thoreau. MTT described the symphony as an epic, and it was. Big, bracing, with sudden and exquisite moments of tenderness nestled among passages of utter fury. I’ve always liked Ives, the Connecticut iconoclast who made his living selling insurance and persisted in writing works that few wanted to hear. But this piece brought him to life in ways I hadn’t heard before—and underscored the majesty and “Americanness” of his often nostalgic vision. A woman I spoke to after the performance summed it up: “This felt almost classical,” she said—especially after Friday night’s foray into the world of John Cage.

I do have one question about biography—where are the women in this series?

During intermission, I cornered the American composer and U-M faculty member Michael Daugherty, who was sitting a few rows in front of me, and asked him what these concerts meant to him:

Word has it that Carnegie Hall is having a tougher time filling its house for these concerts next week than Hill (a larger hall in a far smaller community). It’s a credit to Ann Arbor audiences, as Daugherty reminded me:

Cat Calls, Cheers, and the Glories of Sound – Guest Blog by Leslie Stainton

Photo: From left to right: Jessye Norman, Michael Tilson Thomas and Meredith Monk perform in John Cage’s Song Books during the San Francisco Symphony’s American Mavericks Festival at Davies Symphony Hall in SF on March 10. Photo credit: Kristen Loken.

Editor’s Note: Lobby contributor Leslie Stainton will guest blog the San Francisco Symphony American Mavericks festival throughout this weekend. Her first post is here.

The ride—we’ve definitely moved from journey to ride—continued on Friday night with a rollicking three-hour Mavericks program that included a witty tribute to Beethoven, a tempestuous plunge into the pleasures of sirens and things that go thwack, a surprisingly lyrical piece by the same Henry Cowell who’d shattered any peace on Thursday night, and the evening’s most talked-about event—a gloriously funny, straight-from-the-Sixties, half-hour spectacle by John Cage, featuring Jessye Norman, Meredith Monk, Joan La Barbara, and Michael Tilson Thomas. The latter showed off his prowess at the blender by whipping up a smoothie. (Recipe not included.)

Here’s what Bob Wallin, who sat behind me (and is no musical slouch, being a season ticketholder at UMS, Lyric Opera, and Michigan Opera Theater), had to say about it:

Wallin wasn’t alone. When the lights fell on the last of Cage’s mania, someone in the audience began booing. It’s the first time anyone I spoke to can remember a boo in Hill Auditorium. Was he a plant? UMS’s marketing director Sara Billmann swears not, as does San Francisco Symphony’s Susan Key. So here’s my challenge: will the real booer please come forward?

Out in the lobby during intermission, I encountered Garrett Schumann, a composition student at U-M, who thought it was all great fun. He especially liked it that audience members literally stood up to the booer with cheers, thunderous applause, and a standing ovation. Here’s Schumann’s take:

I later ran into a former music buyer for Borders who felt much the same. “I mean, you come to a John Cage concert, what do you expect? It’s not as if this is 1913.”

Whatever else you thought of the Cage piece—which had to have cost a small fortune, by the way, given all the personnel and technology assembled onstage—it was a hoot to be there. A Happening in 2012 in staid Hill Auditorium? Worth every excruciating minute.

The second half of the program—Henry Cowell’s riveting “Synchrony,” with its gorgeous trumpet solo; John Adams’s aptly named “Absolute Jest,” whose opening strains made hay with Beethoven’s 9th; and Edgard Varèse’s pounding “Amériques,” with no fewer than 12 percussionists and a massive brass section—had me wanting to shout with glee as I left Hill. All through the evening, I kept thinking about sound: what we hear when we’re not really listening, how beautiful something as chilling as a siren can be, how innately musical noise is, how many magnificent and bizarre and thrilling and offputting ways humans have managed to create sound. A bass drum suspended 12 feet in the air, a bassoon played with a violin bow, a heckelphone—who knew?

By the end of the evening, even my seatmate Bob Wallin had forgotten Cage:

First “Mavericks” – Guest Blog by Leslie Stainton

Photo: The SFS percussion performing in Lou Harrison’s Concerto for Organ and Percussion Orchestra as part of the Opening Concert of the American Mavericks Festival in San Francisco. (l-r James Lee Wyatt, Artie Storch, Tom Hemphill) Credit: Kristen Loken.

Editor’s Note: Lobby contributor Leslie Stainton will guest blog the San Francisco Symphony American Mavericks festival throughout this weekend.

For starters, there was the matter of dress: instead of 19th-century penguin suits, the men in the SF Symphony’s opening American Mavericks concert last night wore casual black pants and open-collared black shirts. You could feel their pleasure. That pleasure turned into radiant joy as the evening progressed, and the musicians worked their way through the bracing, at times tempestuous, at times haunting music of Copland, Cowell, Lou Harrison, and the young, Philadelphia-born Mason Bates, who performed onstage in his own evocative “Mass Transmission,” which had its world premiere last week in San Francisco.

Even if you think you hate this stuff—and for those who chafe at dissonance, there was plenty to hate—last night’s concert was a marvel. If only for the chance to see oxygen tanks take a percussive pounding center-stage. If only for the chance to hear Hill’s glorious organ get a workout the likes of which might have made Bach’s jaw drop. If only for the sheer delight of watching pianist Jeremy Denk slam his body into a Steinway again and again and come up beaming.

If only for the brief and almost gossipy talks Michael Tilson Thomas gave before each work on the program. Thomas not only knows these pieces but knew the composers and told stories about each, so as you listened to the works you could picture old Henry Cowell hanging out with an Irish cult in the woods north of San Francisco or Lou Harrison proudly driving one of the Bay Area’s first cars to run on leftover restaurant grease.

A few highlights:

7:17 pm

As the orchestra tunes up onstage—no happy trills here, but rather discordant tones, squeaks, mournful bleats—I read with admiration a short program note by co-sponsor Maxine Frankel, who says she and her husband helped fund these concerts to ensure that UMS “has the flexibility to consider the new, the different, the innovative, and the cutting-edge.” In a country whose public schools are slashing arts education, we desperately need this kind of thinking. Thank you, Frankels.

7:35 pm

Michael Tilson Thomas takes the stage. “What does it mean to be a maverick?” he asks. The next four nights will help shape answers.

7:48 pm

Midway through Copland’s “Orchestral Variations,” percussionists are snapping their fingers. My husband and I look at each other and grin. “This is so refreshing,” he says to me later. “The array of different sounds.”

7:55 pm

Introducing Henry Cowell’s “Piano Concerto,” MTT (as orchestra members call him) speaks of the composer as a Bay Area “maverist” famous for “vast splodges of notes.” Thomas says we can expect to hear traces of Cowell’s prodigious knowledge as an ethnomusicologist—and we do.

7:58 pm

The opening notes of Cowell’s concerto sound like cars in traffic. But then: surprising beauty. I feel for a moment as if I’m at a cocktail party with someone rippling the piano in the background. Jeremy Denk’s face is a wonder: he grimaces, shakes his jowels, heaves his body into the keyboard.

8:06 pm

The piano as machine gun.

8:10 pm

Denk convulses. He’s playing impossibly fast. Chopsticks on speed.

8:14 pm

Utter cacophony suddenly and bewilderingly culminates in an almost kitschy Hollywood ending. We’re done. The audience erupts. My friend Jim Kister, who’s sitting two rows in front of us, and whose musical tastes run to the conventional, takes his time applauding. During intermission I ask him what he thought:

8:28 pm

I ask one of the ushers how she liked the first half. “It’s unique,” she says, tight-lipped. And then: “I’m anxious to see what they do with the oxygen tanks.” She means the string of big tanks parked downstage left, which have yet to be used. There are also big wooden drums, suspended gongs, chimes, a celesta.

8:40 pm

The U-M Chamber Choir takes the stage for Mason Bates’s “Mass Transmission.” Shouts of recognition from friends in the crowd. Bates himself looks like a college kid—skinny, dressed in a pullover and jeans, I think. He’ll function like a DJ on what he calls “electronica”—digital samplings and techno beats.

8:57 pm

This piece is gorgeous. Consonant, accessible. “Maverick” doesn’t have to be ugly, I realize. I didn’t expect to be moved to tears tonight, but Bates achieves it with his lyrical rumination on communication, technology, and the love between a mother and her daughter. Earlier he’s described this piece, about one of the world’s first long-distance communications initiatives, as “basically a story of skyping in 1920.”

9:04 pm

An ethereal ending—tones just drift off, and we’re left to contemplate the (presumably now-dead) real-life mother and child at the heart of this piece, and the way we live today vs. the miracle of this kind of communication nearly a century ago. How clever of Bates to use new technology to simulate and suggest the old. And through it all, the power of the human voice (which Bates says represents “the most beautiful animal warmth we have.”)

9:11 pm

MTT introduces the last piece, Lou Harrison’s “Concerto for Organ with Percussion Orchestra.” The stage is stripped away—just the organ and an array of often bizarre instruments (rasps, rattles, plumber’s pipes …). I’m reminded of the friend who refers to the percussion section as “the toy department.” MTT says, “This concerto represents Harrison’s extraordinary view of the musical world.” It’s got the rhythmic drive of the gamelan, of Africa, hints of 12-tone music, Middle Eastern vocal traditions.

9:20 pm

I’m hearing echoes of “Einstein on the Beach” in the organ’s runs. UMS has truly bookended its Renegade series.

9:25 pm

Medieval sounds. Beauty I didn’t expect.

9:31 pm

More echoes of “Einstein.” Was Glass a disciple of Harrison?

9:40 pm

A rousing evenings ends in a burst of percussive battering that folds into the eloquent ring of a suspended gong. Long fade to silence, and then again, the audience is on its feet. Earlier another friend I’d spotted in the audience told me, “I had a cup of coffee beforehand, because I thought I might have trouble staying awake, but it’s the last thing I needed.

Afterward, I run into Mona DeQuis and a colleague from the DSO shop, who are selling CDs in the lobby. We talk about the evening’s music:

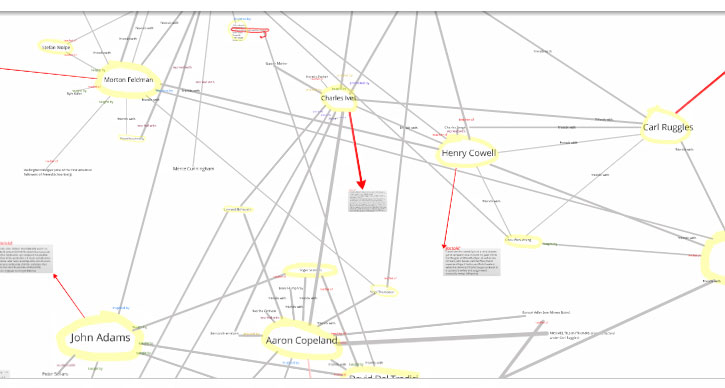

San Francisco Symphony Family Tree

The San Francisco Symphony American Mavericks festival and Michael Tilson Thomas land in Ann Arbor this week. The festival celebrates the creative pioneering spirit and the composers who created a new American musical voice for the 20th century and beyond. We wanted to find out how the composers featured on our Ann Arbor program really hang together. It turns out that they are connected.

Explore the map below to get a sense of the relationships we’ve found between these composers (friends, partners, co-workers, relationships of inspiration…). This map is not a complete picture, but begins to give a sense of the rich musical community which connects these artists and performers.

To explore, click ‘Play’ button. Scroll to zoom in and out and click and hold to move the map. For best experience, click on ‘More’ and ‘Full Screen’ to move to full screen mode. Press ‘ESC’ to exit full screen mode.

Feel free to add yet-undiscovered connections in the comments section below.

We’re thankful to Sam Richards, who compiled the research on which this map is based.

Sam L. Richards is a composer and researcher en route to a doctoral degree at the University of Michigan School of Music, Theatre, and Dance. He frequently collaborates with artists, choreographers, filmmakers, and scientists, and also operates as an interdisciplinary creative consultant for both academic and commercial enterprises.

DJ Chrome Sparks interviews composer/DJ Mason Bates

Mason Bates will be in Ann Arbor on March 22 as part of San Francisco Symphony American Mavericks festival.

Livestream Event with San Francisco Symphony

Join us Sunday, March 11 at 4 pm EST for a live web chat with mavericks Jeremy Denk and Morton Subotnick who will offer insights into the music featured in the American Mavericks festival. Submit your questions and chat with others online.

Stream: http://www.sfcv.org/mavericks

Did you miss it? Is it still a few days away? Check out our Maverick Mondays video series in the meantime.

Maverick Mondays Series

This winter, University Musical Society (UMS) is presenting a 10-week, 10-event ‘renegade’ series focusing on thought-leaders and game-changers in the performing arts. San Francisco Symphony’s American Mavericks festival will close the series.

The second American Mavericks Festival, presented by SFS as part of its centennial season, will tour in its entirety to only two US venues: Hill Auditorium and Carnegie Hall.

We’ll be featuring multimedia content for the performances each Monday as part of our Maverick Mondays series.

A behind-the-scenes look at John Adams’ Infinite Jest:

Find out what Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman sound like through Charles Ives’ Concord Symphony:

Conductor Michael Tilson Thomas and pianist Jeremy Denk discuss Henry Cowell’s piano concerto:

Composer Mason Bates talk about his new work, Mass Transmission:

San Francisco Symphony members and Michael Tilson Thomas remember the first American Mavericks Festival:

Conductor Michael Tilson Thomas talks about the meaning of “maverick”:

Learn about the American Mavericks All-Access Pass!

Renegade Series will shake up your mud months

Some renegades: 1. Einstein on the Beach and 2. Random Dance.

A friend from Minneapolis was visiting earlier this summer, and we got to talking about the dreaded “mud months” up here in the icy north—February, March, alas, even April. Our friend mentioned that she’d spent a week in Arizona last February, but when I said I envied her, she shook her head. “Actually,” she said, “I cut my trip short. I couldn’t wait to get back.”

“What made you do that?”

The cultural life, she said. “There’s no cultural life down there.”

With apologies to the Heard Museum and Ballet Arizona, I think she’s got a point. And I’ve promised myself that this year, no matter how bad it gets, I’m not going to complain when it’s mid-March and I’m shoveling snow for the third time in a week, because the cultural offerings in Ann Arbor more than compensate. (Of course nothing about winter seems bad right now, so long as there are no mosquitoes.)

I’m actually looking forward to the mud months of 2012, because that’s when UMS—in what’s either a brilliant move or a potentially ruinous gesture of faith in the weather gods—is presenting its Renegade series. For me it’s the most tantalizing thing on offer this season, and I’ll be tracking it here on the Lobby, hoping to answer some of the questions I’ve long had about the process of art and art-making, and what makes some artists true outposts of genius and others mere followers. The series starts in January with a reconstruction of the 1976 opera Einstein on the Beach and winds up in late March with the San Francisco Symphony’s “American Mavericks” series, and in between covers a wide and intriguing arc of genres and eras. Beethoven, Gesualdo, Robert Lepage, Jessye Norman, Meredith Monk, Robert Wilson, Philip Glass—they’re all part of it, and they’ll all be here, in spirit or person, as we hunker down under Michigan’s gray skies and count the days until the crocuses bloom.

Because he has as much to do with the evolution of this series as anyone on the planet, I’m starting my personal Renegade “journey” with UMS Programming Director Michael Kondziolka:

LS: What’s the genesis of the Renegade series?

MK: I’ve been having a conversation for 10 years about Einstein on the Beach. And I was also having a conversation with the San Francisco Symphony about a remount of their American Mavericks festival—the first one they did was 10 years ago, in San Francisco. Both of these conversations were long-term and ongoing. And there was a moment when I realized, “Huh! It appears that both of these projects are going to land in the same season.” And when I realized that, I started thinking about the commonalities.

The American Mavericks festival is really all about Michael Tilson Thomas’s vision for a certain kind of American sensibility and “mavericky-ness” when it comes to orchestral music composition—what it means to be American, and what it means to be an innovator and an experimenter. And how can that not in some way relate to Einstein on the Beach, which is, of course, an American work of music, theater, or opera that very much embodied those same ideas of risk-taking, innovation, scale, in creating something really new.

That, strangely enough, collided with another moment that I had last season, where I’m sitting there listening to Pierre Boulez talk about his life, his ruminations on the 20th century, and his role in that. And a student asked a really wonderful question about what the new electronically based media means for music and composition. And Boulez said, “Je ne suis pas un prophète.” “I’m not a prophet. ” And he started to expound on artistic works that are truly important, that are game-changers—works we could never, ever have possibly anticipated, and once we’ve experienced them, could never imagine living without. This was his definition for something that’s truly important.

And I guess it was that statement from such an important intellectual, about art and culture, and these two projects that were long-term conversations, coming together and forming the possibility of a thread of performances devoted to this idea of work that really has changed the direction of the form.

LS: I like the term “game-changers.”

MK: It also felt very zeitgeisty to me. That these things came together at a time when our popular discourse, and our popular political discourse, is just polluted with vocabulary about innovation. “Innovating our way out of the difficulties that we face today.” “Being a maverick.” “I’m the real maverick.” All of this bullsh!t that’s kind of like wallpaper, but there’s no real there there. And of course there are lots of examples of real mavericks, of people who are really innovating, but it also seems kind of … cheap. We’re cheapening the meaning of some of these ideas, of what it means to be a real change-agent.

LS: Why “renegade”?

MK: Ultimately we wanted to choose a word that hasn’t been overused, a word that maybe made people feel both a little bit curious and a little bit uncomfortable. I like the word, because it toggles between the artists, their artistic output, and the audience. What does it mean if you’re an audience member who chooses to go to these sorts of events? Are you a little bit of a renegade? Are you taking a risk? How do you feel about taking that risk, and what do you get out of taking that risk? As consumers of the arts—as listeners and observers—it is the moments when we take risks, or step into something that we have no idea what it is, and are completely bowled over and changed, that matter. Period.

LS: In an ideal world, what do you hope audiences might take away from this?

MK: In a dream world, I want the takeaway to be something really simple. I want people to leave the experience with some sense of that quality of innovation, or change-agency, or specialness, that defines the work as part of this series.

LS: You start with a bang—Einstein on the Beach—and end with another bang, the San Francisco Symphony’s Mavericks series. So how did you decide to flesh out the middle?

MK: How did I want to fill in that time between those two bookends (which is what we’re calling them)? The one thing that was really important to me was that it not focus only on work of the last 50 years. I didn’t want this to feel like a quote-unquote contemporary music series. I wanted to tell a much larger story about moments of extreme change. So I asked Peter Phillips of the Tallis Scholars to put together a Renaissance mavericks program. And we’ve included the Hagen String Quartet’s all-Beethoven concert as a wonderful way of creating an opportunity to understand how Beethoven really changed classical music aesthetics. That’s an obvious concert to include in a series like this. I think Beethoven’s the ultimate maverick.

LS: Beyond just having an interesting cultural experience, and coming away saying, “Wow, I was there for that,” does a series like this have the potential to change our culture by changing the audience? In the best of all possible worlds, how might this shake people up? What might they get from this that goes beyond just the bragging rights, and the curiosity factor?

MK: Obviously, if entering into an unexpected experience opens those kinds of ideas up in an audience member’s mind, that for me would be a very important, possibly transformative takeaway—because we’re reminded, ultimately, of the intrinsic value of the arts and not just the instrumental value of the arts. Now: is that any different from the experience I want people to have when they go to the all-Brahms program with the Chicago Symphony? Probably not.

LS: It does seem that when you’re packaging this as “renegade,” you’re focusing on the process of creating this art, rather than just, “Let’s go hear these great works that are part of the canon.” I mean, how did they get to be part of the canon in the first place?

MK: Exactly.

LS: And what does that mean for us, and how and where we need to move our culture forward?

MK: That’s right. I think you’re right. I also think that accessing a lot of work really ultimately has everything to do with giving yourself permission. Einstein on the Beach, for example, is a five-plus hour work without an intermission …

* * *

In my next post: More from Michael Kondziolka on Einstein on the Beach.

What do you think? Do renegade works fill audiences with renegade spirit? Have you attended a ‘renegade’ work?

Renegade Series

Renegade

The focus on “renegades” in the 11/12 season examines thought-leaders and game-changers in the performing arts and encompasses performances that are part of the UMS International Theater Series, Choral Union Series, Divine Voices, Dance Series, and the Chamber Arts Series. Performances under this umbrella will take place in a ten-week period from January – March 2012 and include:

- Philip Glass & Robert Wilson’s Einstein on the Beach

- From the Canyons to the Stars, performed by the Hamburg State Symphony

- The Tallis Scholars, performing Tenebrae Responses by renegade Italian Renaissance composer Carlos Gesualdo

- Random Dance, a company started by Wayne McGregor , the resident choreographer at The Royal Ballet, Covent Garden, whose groundbreaking collaborations across dance, film, music, visual art, and science is evident in the company’s presentation of FAR

- Robert Lepage’s The Andersen Project, a solo performance created by this Canadian theater visionary that explores sexual identity, unfulfilled fantasies, and the thirst for recognition and fame through Hans Christian Andersen’s timeless fables

- The four concerts of the San Francisco Symphony’s American Mavericks festival. In addition to the three orchestral concerts noted in the Choral Union Series, members of the San Francisco Symphony will present a chamber music concert to close both the American Mavericks festival and the UMS focus on Renegades.

Subscription packages go on sale to the general public on Monday, May 9, and will be available through Friday, September 17. Current subscribers will receive renewal packets in early May and may renew their series upon receipt of the packet. Tickets to individual events will go on sale to the general public on Monday, August 22 (via www.ums.org) and Wednesday, August 24 (in person and by phone). Not sure if you’re on our mailing list? Click here to update your mailing address to be sure you’ll receive a brochure.

Return to the complete chronological list.

Mahler and Me: Preparing Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 from a UMS Choral Union Perspective

As a member of the UMS Choral Union for the past three years, I have thoroughly enjoyed performing some of the great masterpieces of choral music: Handel’s Messiah, Verdi’s Requiem, and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, to name a few. It has only been in the past couple of years though, that I have felt especially drawn to Mahler and his symphonies– the depth of emotion in his music never ceases to affect me in a very profound way, and I have grown to truly love his work. Last year, I learned that the Choral Union would not only be performing Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 in c minor (“Resurrection”), but we would be performing it with the San Francisco Symphony and conductor Michael Tilson Thomas. To say I was excited by this news would have been an understatement! This would be my inaugural performance of one of Mahler’s symphonies and I couldn’t wait to get started! Fortunately, I didn’t have long to wait as the Choral Union, under the guidance of conductor and music director Jerry Blackstone, began rehearsing the piece in late September of this past year.

At our first rehearsal, I sat down before warm-ups began and opened the new choral score of Mahler No. 2 that I had just picked up. I was instantly struck by what I saw on the page: straight-forward rhythms, a fair amount of unison singing between voice parts, and an awful lot of German text (my favorite language to sing in, so I wasn’t complaining). It looked almost elementary in a way, but this is not the case at all, as I have come to discover in the past several months that I have lived with this piece. Also printed in the score are a multitude of dynamics and nearly thirty different markings Mahler included, giving very specific directions on what he wanted from the chorus at various points. For example (translated from German), “Without standing out in the least” and “Somewhat slowing down again” – it is clear all of these nuances were very important to Mahler, and the vision he had for this piece. They have been equally important and emphasized by our conductor, Jerry, throughout our rehearsals as well, with no subtlety being overlooked. We were fortunate enough to have one of our recent rehearsals led by Ragnar Bohlin, the conductor of the San Francisco Symphony Chorus. As Jerry mentions in my video conversation with him, included in this blog post, this was a great rehearsal in which Mr. Bohlin helped us perfect our intonation and unification as an ensemble.

The length of time the chorus sings in this piece is actually quite short; Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 is a five-movement symphony with the chorus coming in halfway through the final movement. The text is taken from a setting of Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock’s Die Auferstehung (The Resurrection). It is quite powerful, and the music Mahler wrote for it very effectively paints the picture of the hope, renewal, and rebirth that the text describes. Jerry has paid careful attention to accurate and unified pronunciation of the German text throughout our preparation of this piece. As the text plays an integral part in conveying the emotion of the music, it has not been uncommon for him to stop us several times while rehearsing until every last vowel and syllable in a phrase is correct and sung beautifully. The orchestration when the chorus enters is minimal but builds to a full, lush sound which includes “the largest possible contingent of strings” (Mahler’s own words), seven different percussion players, the introduction of the organ, and the tolling of deep bells during the final moments of this piece.

Mahler wrote of the final movement of this symphony, “The increasing tension, working up to the final climax, is so tremendous that I don’t know myself, now that it is over, how I ever came to write it.” (Natalie Bauer-Lechner, Recollections of Gustav Mahler) I personally have been humbled by the genius of this piece, and am very eagerly anticipating the culmination of all of our rehearsals when the Choral Union shares the stage with the San Francisco Symphony and Michael Tilson Thomas on March 20 to perform this amazing work. I am quite certain this performance will be one of, if not the highlight of my singing career thus far!

Michael Tilson Thomas Conducting Master Class: Win Your Seat!

As part of the upcoming residency with the San Francisco Symphony, Michael Tilson Thomas will lead a conducting master class on Sunday, March 21 at 10am with members of Kenneth Kiesler’s U-M conducting studio and the University Symphony and Philharmonia Orchestras. As seating for observation is very limited, we’ve decided to reserve 2 seats each for up to 5 lucky winners of this contest!

We’re seeking answers to this question: “What does it mean to be a conductor?” Answers do not have to be related to music. We’re looking for interesting, compelling, and creative entries, and entries can be submitted in any format (writing, music, video, artwork, photos—be creative!).

To enter, please post your entry in the comments section below, and make sure to leave an email address so that we can contact you. Comments can be text or links to external sites hosting photos, music, or video.

UMS staff will vote on the winning entries and announce the winners on Thursday, March 18. Entries must be posted here by 5pm on Wednesday, March 17 to be considered.

We look forward to your responses!