In Closing, An Open Letter to Propeller Theater Company

I will be frank with you: I was hoping to have my world rocked when I walked into your shows this week. I’d heard so much about you, lectures and my brother and my professor and the you tube trailers and the information on the UMS website. You seemed like just the type of company for me. And let me tell you, you fulfilled all of my twenty-two-year-old drama-English-music-geek dreams. You are a company of talented, passionate, dedicated, vocally gifted, really good looking men who make Shakespeare into something brand new while somehow getting closer to the root and core of the text than any production I’ve ever seen.

In short, I wanted my world to be rocked. And rocked it was.

But, see, I’m not all that important. And it’s not because I’m young. It’s not because I’m not a big theater critic, or I’m not some CEO who can fund you. God willing, one day I’ll have the swag to fund the arts the way I think they should be funded. I’m unimportant because you didn’t have to win me over. I already love Shakespeare.

What makes YOU really important Propeller, is not that I, a lover, was rocked. What makes you important is that all the people who are lukewarm about Shakespeare, or don’t know Shakespeare, or who just downright don’t LIKE Shakespeare, are suddenly curious.

I’ve rarely seen an Ann Arbor audience so receptive to pure slapstick and tomfoolery. We’re a stuffy liberal town generally, mixed in with the conservative elements from the surrounding areas who come in for the shows and the restaurants. But there they all sat, two older women in front of me enjoying the performance just as much as I was, as much as my mother (in from the suburbs of Detroit) was, as much as the two women who were sitting next to me speaking in French during the intermission, as much as the younger men with their dates in the front row who got pulled into the action.

Oh I’m sure some people walked out in the middle of the performances insulted, or rolled their eyes, or thought the naked man with a sparkler up his rear was just tasteless. But those, I think, were much fewer and farther between than those of us who absolutely loved what you were doing up on that stage.

Because really, it’s not everyone who can take a piece of history and make it live again. It’s not every company that can keep an audience so riveted that they watch you perform in the lobby at intermission as well as on the stage for two hours. It’s not just anybody who can take a play centuries old and plant it in our heads like it just happened, like we just heard this news, this story, today.

I already love Shakespeare, and it was obvious when I watched the shows you presented. But what was really extraordinary was that I didn’t feel alone in my unashamed and vocal enjoyment of the show. I felt, for one of the very few times in my life as an audience member, as essential to the show as the company was. And as much a part of the group of the audience, as you are Propeller, within your incredibly close knit company.

There are few things more beautiful than watching people around me discover Shakespeare. My own aunts were asking me their questions at intermission and pronounced the production “wild,” at the close, wishing they had been able to see Richard as well.

Which is exactly as it should be Propeller – they should all want more when they leave. Like any brilliant piece of art, they should still be thinking, feeling, reacting, after they walk out the door. It should stick with them. Haunt them like Richard, make them smile like Comedy, explore some part of their humanity like Shakespeare always always does. Anyone who sees this production is thinking, Propeller, where have you been all my life, for I ne’er saw true Shakespeare till this night!?

And that is simply beautiful. There will always be Shakespeare lovers like me. But many of those people who saw you this week will be thinking about Shakespeare in an entirely new way. That is something incredible.

So, my dear Propeller, take this as a open invitation from Ann Arbor. We send our love, our appreciation, and above all our gratitude. A good theater company is hard to find, but you certainly fit the bill. It was an absolute pleasure to have you. Now, come back soon, hear?

Sincerely,

Jen Leija (blogger and adamant fan)

What’s next for Propeller?

We were sitting in the Power Center late yesterday afternoon, watching the changeover from Richard III to Comedy of Errors, and Caro MacKay, executive producer of Propeller, was talking about the shift from Richard’s stark black/white and blood-red world to the trash-strewn, gaily lit, exuberant world of Comedy. “We’re putting some color in the set now,” she said, as stagehands hoisted a panel of graffiti-sprayed shingling onto the big rock ’n roll truss that frames both productions.

MacKay said the idea behind Propeller’s environment for Comedy is “what we call ‘British lager louts.’ A Costa del Sol vacation, where Brits wear silly hats and spend the day drinking lager and hanging around the beach.” She chuckled. “Costa del Ephesus!”

This afternoon was your last chance to visit—at least in Ann Arbor. (The company will do a six-week run at Boston University’s Huntington Theater later this spring.)

A few behind-the-scenes tidbits:

· It’s not a stretch to think of the chorus members as hooligans—soccer fans (witness the jerseys) whooping it up far from home.

· The setting itself is a piazza in the 1980s, a period “quite close to us and probably the height of all this silliness,” MacKay said.

· Designer Michael Pavelka came up with the design of the graffiti himself, then hired a crew of real graffiti artists to render it. But before they agreed to lift a spray can, they made Pavelka swear it was his own design—it’s part of their code of honor not to copy another graffiti artist’s work.

MacKay talked briefly about what’s ahead for Propeller after its international tour of Richard III and Comedy of Errors winds up in August. While here in A2, Propeller received the welcome news that it had received three years’ funding from the British Arts Council—“which means we’re good for four more years,” MacKay said. “We can breathe.” (The news was bittersweet, though, as it came coupled with the announcement that 206 other British arts organizations had received no funding. Many would be forced to close.)

Propeller will reconvene in September and start work on next year’s touring shows, still to be determined. “There’s always one play Ed wants to do,” MacKay said of director Edward Hall. “He struggles a bit to find the other.”

Once they’ve picked the shows, Hall and Pavelka will come up with a set that works for both and begin rehearsals. The 14 members of the current company will get first-refusal rights for the next troupe. It’s a key part of the way this most democratic of theater companies works.

Sometime in the future, Hall wants to do his own cycle of the Shakespeare history plays—the three Henry VIs, Henry V, and Richard III. The working title is Blood Line. MacKay says they’re not sure when they’ll do it, “but we’re working toward it.”

A2 audiences who reveled in the RSC’s first residency here back in 2001—which gave us the three Henry VIs and Richard III—may find this news as tantalizing as I do. UMS, are you listening?

Propeller: Was There a Doctor in the House?

You bet. In fact, there were no fewer than 35 of them at Friday night’s performance of Richard III—med students and house officers, all part of the UM Medical Arts Program, a joint UMS–UM Medical School initiative designed to enrich physician training through exposure to the arts and humanities. Funded by the Doris Duke Foundation, the program gives UM medical students and house officers (aka residents) an inside take on concerts, plays, art exhibitions, poetry readings, and so on—all in an effort to deepen their understanding of the human beings they’ll be caring for as physicians.

Joel Howell, professor of internal medicine at UM and co-director of the program, sent this report on the group’s involvement with Propeller:

Last Wednesday evening some 35 medical students and house officers gathered at A2’s Blue Nile Restaurant to enjoy food, drink, and a stimulating discussion of Richard III—the person and the play. Guided by two splendid Shakespeare experts—UM English Professor Barbara Hodgdon and Carol Rutter of the University of Warwick—the group used the play as the starting point to discuss everything from the roots of Richard III’s behavior, to his choice for future matrimony, to what it must be like to confront death. Along the way the discussion was enlivened by images and quotations from the play.

Two nights later the same group attended Richard. Three reactions:

The amazing thing is not so much the production’s obvious connection with a hospital setting, but the holistic way we should be looking at people. It’s very easy for people in medicine to separate themselves from patients. These events underline that we’re all the same.

It was also nice to see that hospital gowns had backs to them. —Sonali Palchaudhuri, third-year UM medical student

I’m doing a rotation in psychiatry now, and I was thinking about how difficult it would be to diagnose Richard, because he’s such a complex character. Any art is a sharp critique of the boundaries and categories we have in psychiatry. —Eunice Yu, third-year UM medical student

Richard III helps to draw into relief how many people outside the medical world see the hospital setting as creepy and scary. The use of masks [in the production] is in sync with that. I thought of how I have to garb when I go into the operating room or the ICU—how that separates us and makes both doctors and patients feel less human. —John Rhyner, house officer

Propeller: In an Age of Tweets and txts, Musical Signposts

I’m seeing Richard III again today and wish I could do the same for Comedy. I want to catch and somehow memorize all the glorious, intricate, how-the-hell-did-they-do-that details of these two mind-bending productions. I’ve rarely seen a company that so exhaustively squeezes the meaning from a single line of text. Watch Richard Frame dissect and reconstruct and almost literally sculpt Dromio’s pun-packed speech about a spherical wench (in Comedy) if you want to see what I mean.

If you’ve seen either production, you’ll know that music—liturgical, folk, rock, mariachi, tango, rap—underscores and illuminates and just as often undercuts the action onstage. The company describes Richard III as a Requiem Mass, and while I wouldn’t say it’s quite that (though there’s plenty of spilled blood for the literally Mass-minded), it’s far more musical than any Richard I can remember seeing. The production opens with a somber Pie Jesu that lets you hear the gorgeous voices director Ed Hall has assembled in this miraculous little company. (I’m told at least one cast member is a former King’s College choirboy, but he’s far from the only actor with serious vocal chops.)

The Pie Jesu is a perfect example of the egalitarian and deeply collaborative way this company works. The actors went off by themselves, learned and prepared the piece (sung a cappella, like so much of their work), and brought it to Hall. (“Oh, we got to show this to Ed!” actor Chris Myles, who plays Buckingham, remembers thinking.)

Hall was blown away. The piece felt right and quickly found its way into the opening beat of the production, where it sets the tone for everything that follows—all the sacrificial blood-letting, the keening widows and inconsolable mothers, the great dirge that is this play.

“That domino at the very beginning was a great stroke of luck,” Hall said yesterday in a Brown Bag panel at UM’s Lane Hall. “If you get that right, all the other dominoes fall where they should.”

The cast creates a musical soundscape for every show they do—and it’s not just music but offstage sound effects (wind, sirens, horse hooves) and helpful pings that accompany the mention of particular characters (Richmond) or props (the gold chain in Comedy). It’s yet another way Propeller helps audiences who inhabit an age of Tweets and txts navigate the syntactical thicket of Elizabethan English.

With music and sound, as with virtually everything else in these shows, actors do most of the work. They prepare and perform songs, shift sets (all those sinister screens in Richard), deliver props, learn each other’s roles (so that anyone can step in for almost anyone in a pinch). As one company member told me, “If we have a problem to solve, we don’t go for the technological solution.” That’s a huge part of what makes these productions so fun. We’re all—actors and audience—using our imaginations in ways we seldom get to do.

Chris Myles said yesterday that the demands on Propeller actors are so enormous he gets “offstage fright” instead of stage fright. “When I’m onstage and my character’s in a scene, I’m fine. But offstage, I’m changing costumes, delivering props, chanting Latin. There’s always something I know I’m bound to be doing.”

Often it’s singing. Unaccompanied or accompanied by the simplest of instruments—a handheld drum, a wooden stick—the human voice is on magical display here. Hall says music is a deeply “informative” part of Propeller’s work. In the very first rehearsals, when the cast is just sitting around a table reading the script, they’ll talk about where they might want to include musical moments and debate the style of music that might work best in the production. “We spend half our time on YouTube listening to stuff.”

Happily, for another 24 or so hours, audiences in Ann Arbor don’t have to resort to YouTube. We’ve got the real thing.

Tossing Grenades At Shakespeare, and other lessons from Propeller Director Ed Hall

All week long I’ve been hearing people sing the praises of Propeller director Ed Hall. In rehearsals he’s decisive but incredibly open to ideas, firm but flexible, actors say. Company manager Nick Chesterfield told me Hall is “incredibly inclusive. Ed has a very loose way of working, in that he knows what he wants, but he doesn’t lay it on the show. I’ve never experienced a more generous environment.”

All week long I’ve been hearing people sing the praises of Propeller director Ed Hall. In rehearsals he’s decisive but incredibly open to ideas, firm but flexible, actors say. Company manager Nick Chesterfield told me Hall is “incredibly inclusive. Ed has a very loose way of working, in that he knows what he wants, but he doesn’t lay it on the show. I’ve never experienced a more generous environment.”

Having now seen Hall up close, in a riveting exchange Thursday morning with a dozen or so BFA directing students from the UM School of Music, Theatre, and Dance, I get what everyone means. Tidily dressed in a blue Oxford-cloth shirt and slacks—and looking more like a businessman on casual Friday than the director of one of Britain’s most explosive theater companies—Hall spent nearly two hours talking with students and members of the UM theater faculty and gamely fielding questions. He was affable and engaging, and the students clearly gleaned a lot from the exchange. As did I.

About the playwright with whom he’s most closely associated, Hall confessed, “If I go more than 18 months without directing Shakespeare, I go through withdrawal.”

About building a scene: “The opposite is always true. If you have a scene where two people love each other, you have to find out what obstacles they have to overcome in order to love one another.” Ditto with a scene in which two people profess to hate each other—find out what draws them together. “That’s the source of the tension, the drama.”

When directing Shakespeare, Hall often starts with the toughest scene. “If you want to do something big, get it in early.”

On directorial control: “Have a plan, but be critically prepared to let it go out the window. Give yourself up to the process of rehearsal. It’s like stepping off a cliff—if you don’t do it, the actors won’t do it. But they have to know you’re going to be there to catch them. It’s an enormous paradox—trying to control something you’re essentially letting go of.”

Much of what Hall said helped explain the great inventiveness I saw onstage in both Richard III and Comedy of Errors, whose wit and sheer physical brawn had Thursday night’s audience literally oohing and ahhing throughout the evening. Earlier in the day Hall told the UM student directors, “The more I retreat [as a director], the greater the party is onstage.” And oh, what a party.

Now in his mid-40s, Hall has directed 14 productions of Shakespeare. The first, Othello, defeated him. Hall said he tiptoed around the play, trying to do it “right,” and quickly learned his lesson. He now throws “as many grenades as possible against the notion of directing Shakespeare.” That’s not to say he’s not fiercely thoughtful about the texts—as evidenced by these razor-smart productions—but experience has taught him there’s not much to gain from reverence. Hall decries “sunset” acting—where performers look off into the distance with misty eyes while intoning the great lines (“Now is the winter …”). Says Hall: “As a director, you have a duty to cast off the burden of those lines.”

A few more observations that help illuminate the process behind the provocative shows now playing in A2:

“Shakespeare didn’t do scene changes. The moment you do a piece of design that requires the play to stop, you lose momentum.”

“The chorus is context. The context changes and evolves as you rehearse.”

“Acting Shakespeare, you have to be like a good lawyer—you have to be able to deliver rhetoric.”

“There’s no subtext in Shakespeare. The text is where the character is, and the subtext builds itself up from the text.”

“The rehearsal room is a temple for the people you’re working with. It’s a safe place. It’s a private place.”

“The more mistakes you make in rehearsal, and the faster you make them, the quicker you get to the truth. It’s all in the doing.”

And, for the audience, in the going. Go.

Richard III Recap: Taking Sides

We generally do not side with the homicidal maniacs of a given story. For example, we may see Iago’s point of view in Othello, but in the end, after all he does to ruin the lives of those around him, do we really feel all that sorry for his arrest and eventual torture?

We generally do not side with the homicidal maniacs of a given story. For example, we may see Iago’s point of view in Othello, but in the end, after all he does to ruin the lives of those around him, do we really feel all that sorry for his arrest and eventual torture?WITH VIDEO: Sex, Blood, & Body Bags: “Richard III” Opens at Power Center

Nick Chesterfield, Propeller’s company manager, has a soft spot for the Power Center. It was here, in Dressing Room A, where in 2003, during the RSC’s run of Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, Nick learned that his wife, then 26 weeks pregnant, was going to give birth to a son. That boy is now seven years old and already showing a proclivity for the theatrical life, his dad says proudly. “He likes to stay up late.”

Nick is back in town this week with Propeller and happy to be here. By comparison to the RSC, his former employer, he says Propeller is “tiny”—just 14 ensemble members, a handful of stage managers and technicians, and no real home to speak of. “When we don’t have a show we don’t have a company. Our office is where we are. Our theater is where we are. The work is where we are.”

Right now that’s in the Power Center, where an appropriately powerful Richard III—full of blood and plenty of gore, but also, surprisingly and happily, quite a lot of laughs—opened last night. “It’s bloody, but it’s bloody with a twinkle,” Nick told me a couple of hours before the show, moments after the company had finished a long cue-to-cue rehearsal.

While technicians checked sound levels, secured the stage floor, and adjusted lights for the evening performance—Richard’s American debut—Nick talked about the production and the completely seductive way Richard worms his way into audience’s hearts. “You like him, and you’re horrified and repelled by him. He’s horrific but sexy at the same time.” Nick says he’s always interested in seeing how people react to Shakespeare’s most notorious king—and by the way they respond to the show’s considerable violence. Crowds in Edinburgh and Barcelona relished it. Nick was curious to see how the citizens of Ann Arbor would react (see the video below).

I guessed Nick could tell me a few details about the gore we see onstage in this ghoulish, oh-so-delicious show, and I was right. Here are three details to—dare I say?—savor:

- Intestines. Specially created for this production, they’re made of sausage casings stuffed with Readybrek—an instant oatmeal, very powdery, which looks like “gray gruel,” Nick says. Coat them with blood, and you’ve got Buckingham’s bowels.

- Blood. It’s washable, edible, nontoxic, and comes in three thicknesses, including arterial and veinous. Propeller goes through pints of it with every show.

- Body bags. They’re “quite spooky” backstage, especially if you stumble over them, and the company buys them by the dozen. An unsettling revelation: “We’ve discovered they’re not as robust as we’d thought.”

And the chain saw? Here’s everything you need to know:

“The Boys” Are In Town

So I’ve basically been given everything I ever wanted from life: a group of British men, playing Shakespeare, just for me.

That is to say that I got to sit in on Propeller’s cue-to-cue rehearsal Wednesday afternoon before attending the opening night of Richard III. And really, Shakespeare is just so much more legitimate with British accents.

I don’t yet know Richard well enough to say if their craft will be excellent, but there is one thing I can speak to – the sheer, brilliant togetherness of this group of men that makes me think Professor Rutter’s earlier insistence of the troupe as “The Propeller Boys” and “The Pack” is based entirely on fact.

They move like a unit, from ensemble to individual part and back again. Collaboration is everywhere, from “I thought I might stand there,” to “a little more upstage please, because the house is so wide,” each actor having a say in where he goes and knowing exactly why. The equality between directors, techs, and actors is evident in the mutual respect with which direction and suggestion are given and received. In the brief moments when the actors aren’t marking their cue-to-cue, it becomes clear that the ensemble is working as a single unit, a single entity never missing a beat, bringing individuals out of its midst, but always, always returning to the ensemble state, the troupe, which is so much more important than each individual part. They work as a seamless whole putting the focus where it should be : on The Story. The Journey. The thing the audience really comes to live through.

They are comfortable. They are professional. They are, even while marking, a clearly talented group of actors. If I’m any judge at all of the various instruments of torture hanging from the set pieces, I imagine Wednesday evening will be a brutal experience. At this point, the only thing I’m sure of is that “The Propeller Boys” are sure not to disappoint.

WITH VIDEO: From the Bard to the Boardroom…

In all the talk about the mechanics of producing Shakespeare, it’s easy to forget that these plays are also about real issues—the kinds of things we grapple with in our own lives. Richard III, for example, asks about leadership. What does it take to be an effective leader? Strength? Decisiveness? Morality? A willingness to listen to others? (Look at the Middle East today to see how relevant these questions are.)

These same issues surfaced in Tuesday’s workshop, “From the Bard to the Boardroom,” with the Ross Leadership Initiative at UM’s Ross School of Business. Nearly 50 B-school students attended the session in a sunny sixth-floor room, and Carol Rutter, professor of English at the University of Warwick, put them through their paces. She started by having them take off their shoes and just walk around the room, then walk as if they were the most important person there—“as if you were Obama,” she said—and then as if they were the least significant person in the room. And so on. The idea was to understand status and how it shapes physical behavior.

From there it was on to a nonmusical version of musical chairs—an exercise designed to foster teamwork—and finally to a spoken dialogue plucked from Antony and Cleopatra (although the students didn’t at first know that):

A: Welcome to Rome.

B: Thank you.

A: Sit.

B: Sit, sir.

A: Nay, then.

It was fascinating to see the variety of ways two students could interpret that simple exchange.

And of course it drove home the point that with Shakespeare (or any playwright, for that matter) acting is everything. There’s no fixed way to interpret dialogue. It’s a matter of context, status, personality, motives, etc. The B-school students got it right away. (Were they all actors in a former life, or what?!)

The last, and longest exercise in the 90-minute workshop had the students divide into groups and develop a “vision” or “theory” of leadership. Each group received a packet of materials—photos of actors playing Richard III, images of objects and people, passages of dialogue from the play—to help narrate their vision.

Rutter outlined the students’ “brief”: England Corp. has just emerged from a bloody, five-year takeover battle. The Yorks have taken power, the CEO has died, and a fight over his successor is brewing. There are three sons: the hapless, profligate, terminally ill Edward; the suave George; and the ruthless Richard. A fourth possibility lurks outside the “family firm”—Richmond, a Tudor (aka the Good Guy).

Who will run England Corp.? And what qualities did the B-School students think this new CEO should possess?

Rutter explained to me in an aside that her aim with the workshop—which she’s done previously with lawyers—is to cultivate leadership in the very process of trying to define it. Like real-life leaders, the students in the workshop have to examine, analyze, and sort materials they don’t recognize and then make decisions. “The exercise reproduces the process we want them to think about. Process is content.”

I found the outcomes relevant not only to Richard III, but to what’s happening throughout the Middle East, where the very question of succession is sending demonstrators to the barricades.

Some comments from the B-School workshop participants:

“Our ideal leader would have trusted advisors, be educated, and want people to be educated.”

“Good leadership begins with a vision of what leadership is.”

“A good leader should be able to make difficult decisions that people may not agree with.”

“A leader needs to be able to work within existing organizations—and not just be an outsider, a rebel.”

“Hitler was morally bankrupt, but he was a brilliant leader.”

“Leadership starts with integrity.”

On my way out of the workshop, I ran into a first-year MBA student, Nate Fernando, who’d taken part in the session. He told me he’d loved the experience, because fiction “helps you reflect on things in ways that real-life scenarios don’t. It makes you think about people’s motivation, for instance.”

He added, “You see these characters in your own life every day.”

That’s a chilling thought.

Daily Propeller Updates: Links to all the stories from our guest bloggers

Our guest bloggers, Leslie Stainton and Jen Leija, will be blogging all week long on the UMS Lobby. I’ll be compiling links here to each of their stories so that you can easily follow all their reporting from the week. Hope you enjoy! And, please, feel free to comment because Leslie and Jen would love to hear from you.

- Meet Our Guest Bloggers

We’ve asked two community members, Leslie Stainton and Jen Leija, to cover all the Propeller events and report about them here. Our bloggers will have behind-the-scenes access and will bring you recaps and reporting from all of Propeller’s performances and residency activities.

- People Are Talking: Richard III and The Comedy of Errors

Tell us what you thought! This is the place to comment on the performance, and hear what others are saying.

- In Closing, An Open Letter to Propeller

You are a company of talented, passionate, dedicated, vocally gifted, really good looking men who make Shakespeare into something brand new while somehow getting closer to the root and core of the text and than any production I’ve ever seen.

- What’s Next for Propeller?

Sometime in the future, Hall wants to do his own cycle of the Shakespeare history plays—the three “Henry VI”s, “Henry V,” and “Richard III.” The working title is “Blood Line.” MacKay says they’re not sure when they’ll do it, “but we’re working toward it.” A2 audiences who reveled in the RSC’s first residency here back in 2001 may find this news as tantalizing as I do. UMS, are you listening?

- Propeller: Was there a doctor in the house?

You bet. In fact, there were no fewer than 35 of them at Friday night’s performance of Richard III—med students and house officers, all part of the UM Medical Arts Program, a joint UMS–UM Medical School initiative designed to enrich physician training through exposure to the arts and humanities

- Propeller: In an Age of Tweets and txts, Musical Signposts

I suspect it’s the music as much as anything that makes me want to see—to hear—these plays more than once. I suspect that’s the part of Propeller’s work that will linger the longest with me after the company packs its bags and heads back to London tomorrow (may they return!).

- Richard III Recap: Taking Sides

Propeller gives us Shakespeare inside out – covered in blood and steeped in the realities of humanity, that begs us to question who we are. And why, however unwittingly, we side with the diabolical murderer after all.

- Tossing Grenades at Shakespeare—and Other Lessons from Propeller Director Ed Hall

All week long I’ve been hearing people sing the praises of Propeller director Ed Hall. Having now seen Hall up close, in a riveting exchange Thursday morning with a dozen or so BFA directing students from the UM School of Music, Theatre, and Dance, I get what everyone means.

- Sex, Blood, & Body Bags: Richard III Opens at Power Center

Last night, an appropriately powerful Richard III—full of blood and plenty of gore, but also, surprisingly and happily, quite a lot of laughs—opened at the Power Center.

- “The Boys” Are In Town

So I’ve basically been given everything I ever wanted from life: a group of British men, playing Shakespeare, just for me. That is to say that I got to sit in on Propeller’s cue-to-cue rehearsal Wednesday afternoon before attending the opening night of Richard III.

- From the Bard to the Boardroom..

It’s easy to forget that these plays are also about real issues—the kinds of things we grapple with in our own lives. Richard III, for example, asks about leadership. These issues surfaced in Tuesday’s workshop, “From the Bard to the Boardroom,” with the Ross Leadership Initiative at UM’s Ross School of Business.

- A new kind of Shakespeare?

Perhaps the most staggering moment of Monday night’s panel was Professor Rutter’s insistence that the breaking of the fourth wall is pivotal in Propeller’s productions. Simply, that men playing women is not the biggest leap of imagination we all take when we go to the theater, and that if we trust the actors, their craft and skill and dedication, to entertain us, then we will be glad to see actors acting rather than imagining them to be the characters they portray.

- Propeller: What would Brook think?

Peter Brook’s “The Empty Space” published in 1968, has long been a touchstone for anyone who cares about the theater. The book came up last night during Carol Rutter’s energetic talk at the UM Museum of Artabout the Propeller Theater Company and its uniquely “rough” style of performance.

- Propeller: Q&A with UMS Programming Director Michael Kondziolka

For years, Michael Kondziolka, UMS’s Programming Director, has been my go-to guy for all things cultural. If Michael says see it (as he does about Propeller), I move heaven and earth to heed the call. So I asked him how Propeller caught his eye…

- Caro MacKay, Producer for Propeller, Shows Some Love for Ann Arbor Audiences

Caro MacKay, executive producer of Propeller, will zip into Ann Arbor to see her company in action, but over the weekend she was at home in London, where I reached her by phone. The former Royal Shakespeare Company producer knows us well—she was here for both the first and second RSC Ann Arbor residencies, in 2001 and 2003.

A new kind of Shakespeare?

The very British, and very emphatic, Professor Carol Rutter of University of Warwick presided over Monday evening’s lecture festivities (“An Introduction to UK’s Propeller Company”) at UMMA. And I must be completely candid – my first thought was that I was definitely the youngest person in the room. In a crowd of 40 plus people, my 22 years old was a drastic change from a median age of 45. But it’s clear from the presentation that followed that UMS and indeed, Propeller, is a new rather than an old look at Shakespeare.

Looking at the presentation of photographs behind Rutter, I’m already entranced with the visual extremes to which Propeller seems to go. Blood splattered on the stage, half-masked faces, sparkling red heels on a devilishly smiling actor. An entire set in twenty small suitcases. I caught a few comments about the goal of Propellor as a company that “would build the set with people,” that had “the ability to travel light and tour anywhere.” But what stopped me entirely was Rutter’s statement about the type of theater I was about to see. She said it was playful, as I personally believe Shakespeare should always be. That it was demystifying, as I wish all Shakespeare lovers would believe it should be. And then she said that it was, “Frequently dangerous, always disruptive … and constantly provocative.”

And that, my dear friends, is just exactly what Shakespeare is.

Shakespeare is also the raucous run of an all-male stage – which Propeller embodies with the actors who call themselves ‘the Propeller boys’ and ‘The Pack’. Professor Rutter spoke about the somewhat controversial all-male make up of the company after which I asked a brief question about whether this persuasion seemed to alienate female theatergoers. The negative answer in itself was not as fascinating as her explanation: that men playing women allows the men to be brutal in ways they cannot be with female actors and that it frees a woman from being the paragon of theatrical beauty, talent, and grace, taking on the many abuses that Shakespearean women undergo. Perhaps the most staggering moment of this explanation was Professor Rutter’s insistence that the breaking of the fourth wall is pivotal in Propeller’s productions. Simply, that men playing women is not the biggest leap of imagination we all take when we go to the theater, and that if we trust the actors, their craft and skill and dedication, to entertain us, then we will be glad to see actors acting rather than imagining them to be the characters they portray.

Since the first question after the end of Professor Rutter’s presentation was about whether the company edits the original text or not, I can’t imagine everyone is excited to see the gritty, controversial, upcoming productions of Richard III and Comedy of Errors. But as an unconventional (read: young) lover of theater, the English language, and the incredible combination of the two in Shakespeare, I can unequivocally say that I am.

Propeller: What would Brook think?

Peter Brook’s The Empty Space published in 1968, has long been a touchstone for anyone who cares about the theater. The book came up last night during Carol Rutter’s energetic talk at the UM Museum of Art (UMMA) about the Propeller Theater Company and its uniquely “rough” style of performance. Rutter, a professor of English at the University of Warwick and UM grad, admits she stayed away from Propeller for more than a decade because she thought they’d be too “adolescent” for her tastes. She finally went two years ago, “and I thought, where has this been all my life? I’d finally grown up enough to find all the childlikeness and playfulness of the ensemble delightful.”

Rutter calls Propeller a perfect example of Brook’s idea of “rough” theater, which he describes as:

Salt, sweat, noise, smell: the theater that’s not in a theater, the theater on carts, on wagons, on trestles, audiences standing, drinking, sitting round tables, audiences joining in, answering back: theater in back rooms, upstairs rooms, barns; the one-night stands, the torn sheet pinned up across the hall, the battered screen to conceal the quick changes.

It’s the Elizabethan stage, Punch and Judy, plays in prisons and on streets. Risky theater that lives by its wits. Theater stripped to its essence—which is to say theater as acting.

Rutter says, “What I like best is to see actors at work. I don’t want the production to get between me and the actor.” Propeller “asks actors to be the material of their own production.” That’s to say they’re not only characters and chorus, but the scenery itself. Instead of a door, you get a pair of players holding a doorknob. You get the wonderful, whimsical apparatus of the theater: false noses, garish tights, tutus and wigs, buckets of blood. Presentational—not representational—theater.

Rutter: “You’re so close to the story.”

Pit this against what Brook calls “the deadly theater,” which we’ve all seen. Conventional, commercial, safe plays, staged in trite, often sentimental ways. Old jokes, predictable effects, creaky machinery, overproduced sets. “The Deadly Theater takes easily to Shakespeare,” Brook writes:

We see his plays done by good actors in what seems like the proper way—they look lively and colorful, there is music and everyone is all dressed up, just as they are supposed to be in the best of classical theaters. Yet secretly we find it excruciatingly boring—and in our hearts we either blame Shakespeare, or theater as such, or even ourselves.

Rutter talked last night about a recent RSC production of Lear, which had an ensemble of 23 actors, ten of them spear-carriers, “doing zilch. Like cabbages.” Great in its heyday, the RSC—and they’re not alone—has become brand-name theater, Rutter believes. Lavish, heavily subsidized, unable or unwilling to take risks.

Too big to fail.

“Which is why,” she says, “we who want Shakespeare to live forever will always need companies like Propeller.” Maverick companies with anarchic ideas, free to play and to fail. Rough theater.

“What does Shakespeare gain from this collaboration?” she asked toward the end of her talk. “Those are questions I leave to you.” Comments welcome…

Caro MacKay, Producer for Propeller, Shows Some Love for Ann Arbor Audiences

Later this week Caro MacKay, executive producer of Propeller, will zip into Ann Arbor to see her company in action, but over the weekend she was at home in London, where I reached her by phone. The former Royal Shakespeare Company producer knows us well—she was here for both the first and second RSC Ann Arbor residencies, in 2001 and 2003. I asked her why she wanted to bring Propeller here…

CM: Having done two seasons at Ann Arbor, I know your enthusiasm. But you’re also a tremendously thoughtful audience, and you’re obviously in a university town, so there’s great intelligence there, and I just thought you’d really like this company. Propeller offers something different—it’s very immediate and physical theater, but it’s also very intelligent Shakespeare.

You even decided to premiere Richard III here.

CM: Yes, it’s premiering in Ann Arbor. That’s really exciting for me. I’m thrilled that we’ll be presenting both shows [Richard III and The Comedy of Errors] because you will see the measure of what the company is capable of. And the different actors—they’ll be doing something in one show and something utterly different in the other show.

What was it about Propeller that made you want to get involved with the company?

First, their love of the text. It is there in all the shows. The text is very true to Shakespeare’s text. The second thing is, for me, every really, really, really good director is a great storyteller. And I think the way that [Propeller director] Ed Hall tells the actual story is terrific. That’s what leapt out at me. It’s the clarity—the actual clarity of the story, so that you can follow it. And the energy. Propeller is enormously physical.

Tell me about the ensemble. They’re onstage the whole time, for both shows, which is so intriguing.

It’s very particular to Ed’s work. And it means everybody is in rehearsal all the time. They’re in there all the time, all the day. You’re never only called for the scenes that you’re in. Rather than having just a half a dozen people working lines in rehearsal room, you’ve got 14. Everybody is always concentrated. I just think it is a true ensemble—everybody is looking at the scene that is the play and asking what is that scene doing for the play? What is the story line behind it?

It’s an all-male ensemble. How’d a woman like you wind up being the producer?

It’s quite funny, isn’t it? A girl to be running an all-male Shakespeare company. It took me a little while for me to really go, yes, I believe in this. But after a couple of shows, I got the clue. What you find with just having one sex is that actually you’re listening to the words. Whether you’re a male or a female, you’re just listening to what Shakespeare is saying and asking, what does that mean? That’s what it allows you to do—to scrape away the sexual politics and just listen to the words.

VIDEO: Men in Dresses! Blood & Gore! Watch the Propeller Trailers

Next week, the UK’s all-male Shakespeare troupe Propeller (led by acclaimed director Edward Hall) will be taking Ann Arbor by storm with stellar new productions of Richard III and The Comedy of Errors. The shows have been receiving rave reviews and great word-of-mouth from audiences. The video trailers for both productions are here — and they are pretty awesome.

If you want to learn more about the company, you can check out their blog and this blog post from UMS staffer, Mary Roeder, who visited the Propeller company in the UK while they were rehearsing Richard III last fall.

This Day in UMS History: Royal Shakespeare Company History Plays (March 10-18, 2001)

Ten years ago today, UMS audiences began a great experiment — the Royal Shakespeare Company presenting four Shakespeare History plays (Henry VI, parts i, ii, and iii, and Richard III) over the course of 27 hours with lunch and dinner breaks built in. The productions, directed by now-RSC artistic director Michael Boyd, marked the beginning of a long relationship between the University of Michigan and Ann Arbor with the RSC. Over the past decade, this partnership has included three major residencies, as well as workshopping new plays on the U-M campus. Each residency was accompanied by dozens of free educational events for students and the public-at-large.

Those who were present will no doubt fondly recall some of these images from the productions:

The three Henry VI plays were presented at 11 am, 2 pm, and 8 pm on a Saturday, with audiences returning on Sunday for the climactic production of Richard III. (There was also one mid-week cycle, which ran Tuesday, Wednesday [both matinee and evening], and Thursday.) Since that season, UMS’s theater programming has expanded significantly, with an annual commitment to presenting both live and high-definition broadcasts of international theater — including this season’s productions of Richard III and The Comedy of Errors by another British theater company, Propeller. Like the RSC, Propeller presents contemporary interpretations of Shakespeare and works with an ensemble cast; unlike the RSC, Propeller uses an all-male cast to present the Bard’s works, as would have been the case in Shakespeare’s day.

Richard III opens at the Power Center on Wednesday, March 30, and The Comedy of Errors opens the following evening. Tickets can be purchased at www.ums.org or by calling 734-764-2538.

Dispatch from across the pond: Shakespeare is on the way!

Yesterday was a very important day. In addition to marking the start of the one week countdown to our nation’s Thanksgiving binge, it was also the opening of Propeller’s production of Richard III at Coventry Belgrade. Propeller, an all-male Shakespeare company, appears here in Ann Arbor March 30 – April 3, 2011 with both Richard III and The Comedy of Errors.

At the end of last week I took a rather last minute trip to London for a long weekend (Who takes a last minute trip to London you might ask? Someone with a friend employed by an airline. The fabulous life is achieved by things like knowing pilots. And stage managers for important theater companies. And being granted a vacation day allotment. Dumb luck and circumstance.). While there, I was able to pop in on Richard III rehearsals for a couple of hours.

I had recently learned via Facebook that my friend Laura, whom I met while she was the deputy stage manager (DSM) for the Globe Theatre’s production of Love’s Labour’s Lost (presented by UMS in October 2009) that she would again be touring to Ann Arbor…this time as the DSM for Propeller! Exciting, right? So of course, when I found out I’d be going to London, I asked her if I could stop by rehearsals.

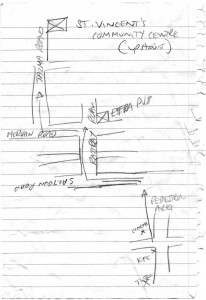

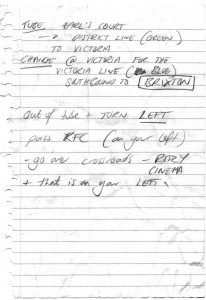

Laura gave me a call time of 9:45am on Friday and told me to report to Brixton St. Vincent’s Community Centre where the company was rehearsing. I asked her for explicit instructions on how to find the place. Being the well-armed stage manager that she is, she whipped out a spiral notebook and pencil (stage managers never use pens), drew me a map (Exhibit A), and illuminated it with written instructions (Exhibit B).

Friday morning came along, and I found the place with no trouble, even arriving with time to spare, a testament to Laura’s fine directions. I met a few members of the cast and crew and Propeller’s director, Edward Hall. The space was very small (read: I couldn’t hide like I had planned), and I was nervous that my presence would be an intrusion. Turns out my fretting was for naught, as everyone greeted me warmly. I was met with a cup of tea and questions like…”Is Michigan cold?” Yes. “Will it be cold when we’re there?” Probably. “Is Michigan like Minnesota?” They’re both funny-shaped and cold. So yes, probably.

So what should you as a potential audience member know about this company? Well, as their website says, Propeller “seeks to find a more engaging way of expressing Shakespeare” and “[mix] a rigorous approach to the text with a modern physical aesthetic.” In the case of Richard III this means the inclusion of the decidedly non-Shakespearean electric guitar, among other things. A crucial part of every Propeller production is the music. All of the music in their shows is either written by the company or sourced from music they know, and they have a tradition of producing most, if not all, sound effects live from the stage. Jon Trenchard who plays Lady Anne in Richard III (yes, you read that correctly…remember that part where I said this is an all-male company?) and Dromio of Ephesus in Comedy, is also creating and arranging music for both productions. In two incredibly entertaining installments, Jon blogs about the musical rehearsals for Richard III. They really seem to know their stuff and think very carefully and deliberately about the musical components of each show. I didn’t understand half the jargon contained in either post which is pretty solid proof of that.

Aiming High: the Richard III Requiem Mass

Judgment Day: RICHARD III The Musical?

I was really excited by what I saw – the aforementioned guitar, the triple-duty gurney/throne/horse prop, the costume and stage sketches posted on the walls, the abundance of scythes and other torture instruments (including the thing that looked like it might be used for the extraction of a giant molar), the lovely singing, and, of course, the acting. Ann Arbor audiences, you’re certainly in for a treat!

Before I leave you with some photos from the Richard III rehearsals, I wanted to offer one last highlight. I learned from Laura that during the rehearsal day prior to my visit, the group had had an epic four hour long notes session. So, the bulk of what I was seeing was the company’s rehearsal of some of these notes. The scenes to be addressed were each prefaced in a humorous fashion by Mr. Hall…some personal favorites: “That went to rat sh*t yesterday. So let’s put a bandaid on that.” and “Could we look at the other massive car crash?”

(I hope he doesn’t mind that I was taking my own notes!).