10 Things About Robert Mapplethorpe + ‘Triptych’

Learn about photographer/artist Robert Mapplethorpe’s legacy before UMS’s world premiere of Triptych: Eyes of One on Another on March 15 & 16, 2019.

Self Portrait, 1988 © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission.

1. Robert Mapplethorpe didn’t begin his career as a photographer

In his early career, Mapplethorpe created assembled constructions and collages. These works tended to be mixed medium, combining painting, found objects, and cut outs of pornographic magazines and religious postcards. He took up photography after the encouragement from his friends John McKendry, a curator, and Sam Wagstaff, a gallery owner and Mapplethorpe’s eventual lover.1

2. His early photography was deeply rooted in 1970s New York

Mapplethorpe and his close friend and roommate Patti Smith were involved in the 1970s New York music and art scenes, frequenting legendary venues such as Max’s Kansas City and CBGBs. Mapplethorpe photographed two iconic album covers of that era: Patti Smith’s Horses and Television’s Marquee Moon. During this time, Mapplethorpe also was a staff photographer for Andy Warhol’s Interview Magazine.2

3. Mapplethorpe’s work was often controversial

During his time of rising popularity, Mapplethorpe photographed the New York’s BDSM scene in which he was involved. With regard to his work, Mapplethorpe stated, “I don’t like that particular word ‘shocking.’ I’m looking for the unexpected. I’m looking for things I’ve never seen before … I was in a position to take those pictures. I felt an obligation to do them.”3

Mapplethorpe’s work has the power to upend beliefs about black/white, female/male, queer/straight, art/porn, sacred/profane, classical/contemporary, low art/high art, and political/personal.

4. Mapplethorpe was a go-to photographer for celebrity portraits

He shot portraits of Andy Warhol, William Burroughs, Patti Smith, Philip Glass, Iggy Pop, Peter Gabriel, Grace Jones, Cindy Sherman, Truman Capote, and, of course, himself!4

Alistair Butler, 1980 (c) Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, used with permission.

5. There is a strong sense of classicism throughout his work

Mapplethorpe had an intense focus on balance, harmony, and order. Traces of classical art can be found in his treatment of the body, which was often reminiscent of sculpture. Throughout his career, he also recalled classical composition in his photography of flowers and other still life objects. This often created a tension in his work between the erotic subject matter and his “high art” depictions.

About the Production…

6. A theatrical world premiere

UMS presents the world premiere full theatrical staging of Triptych: Eyes of One on Another (the concert version premieres at the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles on March 5). In addition to vocal ensemble Roomful of Teeth and a chamber orchestra, UMS’s production at the Power Center will feature large-scale, theatrical projections of Mapplethorpe’s work (which may include graphic, sexually explicit content).

7. Bryce Dessner’s Cincinnati connection

Composer Bryce Dessner recalls the controversy and censorship trial of Robert Mapplethorpe’s 1989 collection of photographs at the Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center…

8. A broadening of perspective

Librettist Korde Arrington Tuttle found profound meaning in Mapplethorpe’s perspective during his college years…

9. Roomful of Teeth

The innovative, GRAMMY-winning vocal collective Roomful of Teeth was recently profiled in The New Yorker: “From death metal to throat singing to alpine yodelling, the experimental group is changing what it means to harmonize.” Take a listen:

10. A 30-Year Reflection

This premiere event takes place 30 years after Robert Mapplethorpe’s untimely death from AIDS on March 9, 1989. UMS is proud to present this work on the influence of Mapplethorpe’s bold, voracious view of how human beings look, touch, feel, hurt, and love one another.

Experience Triptych: Eyes of One on Another, March 15 & 16, 2019 in the Power Center.

Embrace, 1982 (c) Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used with permission

Sources:

Artist in Residence Spotlight: The Power of Being

This post is a part of a series of posts from UMS Artists in Residence. Artists come from various disciples and attend several UMS performances throughout the season as another source of inspiration for their work.

This post is a part of a series of posts from UMS Artists in Residence. Artists come from various disciples and attend several UMS performances throughout the season as another source of inspiration for their work.

Qiana Towns is author of the chapbook This is Not the Exit (Aquarius Press, 2015). Her work has appeared in Harvard Review Online, Crab Orchard Review, and Reverie. A Cave Canem graduate, Towns received the 2014 Gwendolyn Brooks Poetry Prize from the Society for the Study of Midwestern Literature. She is a resident of Flint, where she serves as Community Outreach Coordinator for Bottles for the Babies, a grassroots organization created to support and educate the residents of Flint during the water crisis.

Each year I choose a theme to live by – a leitmotif to carry me through all of the beauty and chaos a year can bring. I like to think doing this offers some perspective and guidance for how to conduct myself. It also seems to provide a starting point for engaging with the world around me.

2017 is the year of no apologies. Though if I’m being honest, there will likely be a few apologies. It’s just how I was raised and I certainly don’t want to become a microcosm of the current government administration.

What I mean to say is this: My plan for 2017 is to be the artist I’ve always wanted to be. And I do mean artist. While, quite literally, poetry has been my primary vehicle for creating art, I’m more than ready to — to continue the metaphor — get a new car. Or a bike. No apologies.

Photo: RoosevElvis. Photo by Kevin Hourigan.

Even before I attended the performance of The Team’s RoosevElvis, I imagined creating a performance piece based on a road trip I took from Los Angeles to the Bay Area just a few years back. It was a road trip inspired by Kerouac’s On the Road…but blacker and powered by all of the feminine energy of the women writers I’d connected with in L.A. I made several stops along the way including a stop at Bixby Bridge (near the location where Kerouac penned Big Sur). There were no alter-egos, no drugs. Although, whenever I tell this story back home people ask if I was high on something. Maybe they can’t fathom a woman traveling in unfamiliar territory alone, and along some of the most frightening highways and pulchritudinous sights in America.

The road trip that is RoosevElvis drove the audience through an exploration of self-identity. It reminded me of the part of America that still wants to define itself as the land of the free and the home of the brave. I might argue that it is neither, but that’s a discussion for another time. Either way, RoosevElvis seemed to ask the audience to pause and consider how each of us embrace or reject ideas about who and what we are in America. The performance piece I’m working to create may answer this question or it may add other questions to the list. It may do both.

Photo: portrait of myself as my father. Photo by Anna Lee Campbell.

Somewhere in my creative process I have coupled the aforementioned experience with the sheer rawness of Nora Chipaumire’s portrait of myself as my father. If I had a comfort zone, “portraits” would probably have taken me out of it. I thought to myself, “Isn’t this what art is supposed to do?” I need to do more of this. Meanwhile, I clandestinely watched as the people around me began to shift as the performance carried the audience through exploration of sex and the black male body. It got hot in there. Even after the artist shifted to other subject-matter, the heat of the moment did not leave us and Chipaumire did not offer a single apology.

I have not given myself any deadlines or requirements for the development of my first performance piece. I have only given myself permission to embrace the fullness of being an artist. Actually, I’m sure this is enough.

Follow this blog for more updates from Qiana throughout this season. Learn more about Renegade this season.

Unlocking the Technology and Technique Behind Complicite’s The Encounter

Editor’s note: On October 2, 2016, Complicite’s The Encounter Sound Designer and Olivier Award Winner Gareth Fry visited Ann Arbor on behalf of a partnership between UMS and the Ann Arbor District Library. Jocelyn Aptowitz attended the workshop. The Encounter comes to Ann Arbor March 30-April 1, 2017.

Photo: Simon McBurney during a moment in The Encounter. Photo by Gianmarco Bresadola.

There is whisper coming from behind me. I am in Brazil, and someone is moving around me, telling me a story. I can hear the Amazon Rainforest: a mosquito buzzes in my right ear, the faint gurgle of a river up ahead.

When I open my eyes, I have not moved from The Secret Labin the basement of the Ann Arbor District Library. I am at my table; the whispering, the mosquito, and the river were all a trick courtesy of binaural sound.

Gareth Fry, the sound designer for Complicite’s The Encounter shows us only a small slice of the experience that we could expect at the performance this spring, following a three-month Broadway run this fall. It’s no wonder The New York Times calls this production “one of the most fully immersive theater pieces ever created.”

So, what is binaural sound?

One way to describe the experience of listening to a binaural recording is that it is listening in 3D. Unlike conventionally recorded sound, binaural recordings give the listener the sense of the relationship of between where the sound was produced in relation to the microphone which recorded the sound. In fact, binaural recording replicates the volume, timing, and distance of sound so perfectly that one feels immersed in that environment.

Why is binaural sound special?

A conventional microphone has no sense of space. Any sound that is recorded on a conventional microphone is generally broadcast directly back to the center of the room. Binaural recordings, on the other hand, allow the audience to use their hearing to calculate an environment around them. Humans are naturally equipped to have a very accurate sense of direction with respect to sound. Binaural sound uses shading (how our right and left ear hears sound differently) to reproduce the processing our brains automatically do for us in a given environment.

How is binaural sound recorded?

Binaural recordings are created using a binaural head, which contains a microphone in each ear. Fun fact: The binaural head was first unveiled at the 1933 Chicago World Fair by AT&T. Fry’s own head for The Encounter is nicknamed Frida, and The Encounter team flew to the Javari Valley in Brazil with their equipment to record the sounds heard in the performance.

What are the challenges associated with binaural sound?

Because binaural recordings recreate the environment of space that the sound was recorded in, it picks up a lot of ambient noise. This is a challenge for sound because all the recordings need to be very carefully captured to avoid unwanted noise. For example, when recording for The Encounter, Fry and his team had to be very careful not to whisper or use any noisy equipment while recording.

The Ann Arbor District Library has binaural recording equipment available for circulation! For more information, please email tools@aadl.org, and make your own field recording.

See The Encounter in Ann Arbor on March 30-April 1, 2017.

Artist in Residence Spotlight: Taking part in the Performance

This post is a part of a series of posts from UMS Artists in Residence. Artists come from various disciples and attend several UMS performances throughout the season as another source of inspiration for their work.

This post is a part of a series of posts from UMS Artists in Residence. Artists come from various disciples and attend several UMS performances throughout the season as another source of inspiration for their work.

Barbara Tolzier works in photography with forays into media and video. After an engineering career that took her to Pennsylvania and the Netherlands, Barbara reconnected with photography in 2009 — she studied with Nicholas Hlobeczy in college — and in 2012 started taking photo classes at Washtenaw Community College, where she went on to earn an Associate’s Degree in May of 2016. She has exhibited at the Ann Arbor Street Art Fair, The Original and in group shows at 22 North Gallery, Washtenaw Community College, and Kerrytown Concert House. She lives and works in Ann Arbor.

Without any introduction, Igor and Moreno walk past white curtains onto a white stage. They stand there, looking at the audience. We know they can see us because the house lights are up.

They start singing. Eventually, they start bouncing. Then, while bouncing, they remove their street clothes (jackets, jeans, socks and shoes) to reveal t-shirts and gym shorts.

The two men bounce. They look at the audience. The lights dim, their song ends, and they continue to bounce, moving around the stage, occasionally hitting the place where the show’s floor is just-that-far-away from the underlying stage and making a different sound as their weight lands on it.

There is nervous laughter as the audience isn’t quite sure what is going on, except bounce bounce bounce, sometimes quieter, sometimes louder, sometimes upstage, sometimes downstage. Bounce bounce bounce. The rhythm is steady, the performers are watching us, interacting with us, bouncing through the aisles. Bounce bounce bounce.

There is no music. Only bounce. Only the interaction between the performers and the audience. The sound is reminiscent of so-called minimalist music. Bounce bounce bounce. Pattern but no pattern but exertion and bounce. And watching. They are watching us watching them.

Who are they seeing, those two men bouncing on a white stage? What do they expect from us?

They expect us to share in their experience. We do not bounce, not most of us, anyway. They bounce from backstage with stacks of red cups, those red cups that are so ubiquitous when the students return. We laugh, and we share the cups, passing them from viewer to viewer. And then comes the Vernor’s. And more laughter. And we pass bottles from viewer to viewer, each person taking a token amount, ensuring everyone can share in the boon.

And for the whole time we watch them bounce bounce bounce.

And for the whole time we watch them bounce bounce bounce.

It’s hypnotic. Bounce bounce bounce. Bouncing all over the stage, single and together. Occasionally one will leave the stage, leaving the other to occupy our attention, and returns bouncing to the same rhythm when as he left.

There’s an interlude, during which the performers change costumes by removing t-shirts that they’ve picked up on one of their backstage jaunts. The lights start to change: dimmer, warmer, more intimate. They see us with their costumes, shirts with eyes printed on them, as we watch them.

Bounce bounce bounce. Slowly we become aware of a droning sound, the sound of electronic feedback. Bounce bounce bounce morphs into a pas de deux as the sound intensifies. The eye shirts are removed. They stop watching us. The rhythm remains but the dance becomes less and less bouncy. They watch each other. The sound is a heartbeat. Sound replaces bounce. The men dance with each other instead of dancing to the audience. They whirl and spin and spin and whirl. We can hear their breathing. They sing to each other. They don’t see us, even when they face us. They spin. They spin. They spin. Their breath gets faster faster faster. The heart beats faster faster faster. The sound stops.

The pair dance off of the stage. The lights come up. It is finished.

I leave the theater in the quiet cold January night, texting one word: wow.

I realize I have learned something. Minimalism can evoke story. Oddness can influence emotion. Intensity can spur contemplation. Audience and artist together make the work.

Follow this blog for more updates from Barbara throughout this season. Learn more about Renegade this season.

Artist in Residence Spotlight: Appreciating the Whole Performance

This post is a part of a series of posts from UMS Artists in Residence. Artists come from various disciples and attend several UMS performances throughout the season as another source of inspiration for their work.

This post is a part of a series of posts from UMS Artists in Residence. Artists come from various disciples and attend several UMS performances throughout the season as another source of inspiration for their work.

Simon Alexander-Adams is a Detroit-based multimedia artist, musician, and designer working within the intersection of art and technology. Simon has composed music for a number of short films, animations, and theatrical and dance performances. His compositions have been performed at international festivals, including the Ann Arbor Film Festival and Cinetopia. He also performs frequently on keyboard and electronics with the glitch-electronic free-jazz punk band Saajtak. Simon earned his MA in Media Arts in 2015 from the University of Michigan’s School of Music, Theatre & Dance.

Sometimes I see a performance that has a clear and direct impact to my work. Performances such as Royoji Ikeda’s superposition and Amon Tobin’s ISAM steered my focus towards multimedia performance that combines music, visuals, and staging, and pointedly influenced my visual and sonic aesthetics. Then there are the shows that are highly impactful, and I know will influence me, but I can’t quite put my finger on how. It’s this type of artistic understanding that grows over a lifetime – the complexity of long forms, the nuance of symbolism, and the power of ambiguity. These shows are undeniably inspirational, yet the substance of their awe is often elusive.

One such performance I saw recently was the Batsheva Dance Company’s Last Work. The movement was highly compelling, and the music and sound design fresh and beautifully unexpected. It worked on all technical levels, and yet this wasn’t what really made it powerful for me. It was the form – the way the piece unfolded – that struck me. Without the quality of the components, the whole would have suffered, but ultimately it was the gestalt that stuck with me more so than a particular element.

Soon after seeing Last Work I dived into developing interactive visuals for Saajtak, a new-music / avant-rock quartet I play with. The challenge was to develop visual content that contributed to a multimedia experience, without overshadowing the musical performance. As our music consists of long, intricate forms, I wanted the visuals to compliment this complexity.

The process, which took place over about a week of work around the clock, felt like a blur. I was in what both musicians and athlete’s alike call the “zone.” While there isn’t a direct relationship between Last Work and my work for Saajtak, Last Work was an important piece, among many others, that contributed to my greater understanding of long forms in multimedia contexts. Seeing the piece also energized me in a way that I leveraged in my own art making. My art draws from personal experience – I fluctuate in waves of intake and expression – absorbing moments of life, and synthesizing them through the creative process.

Video created by Ben Willis, Saajtak bassist and former UMS artist in residence.

Follow this blog for more updates from Simon throughout this season. Learn more about Renegade this season.

On Being African at the University of Michigan

Moment in portrait of myself as my father. Photo by Gennadi Novash.

Nora Chipaumire’s portrait of myself as my father is a piece of many origins. All aspects of Chipaumire’s identity as an African, a woman, a black woman, an African woman, and an African-American woman seep into her work. In this “love letter to black men,” she explores the complex tangle of conceptions, stereotypes, expectations, vulnerabilities and strengths of the black African male.

Zimbabwean influences, unique venue

A dizzying combination of Zimbabwean and African dance traditions, garb, and music help to tackle these big questions. Traditional Zimbabwean music rooted in polyrhythmic beats combines with Zimbabwean dance, an art form which requires a considerable amount of strength and agility to perform. Chipaumire uses these tools to celebrate the strength, resilience, and inherent defiance of the black body. She fuses her Zimbabwean heritage with her contemporary dance training to create this piece. Wearing traditional African gris-gris (a talisman used in Afro-Caribbean cultures for voodoo) with football pads, Chipaumire explores the black male at the crossroads of two cultures and identities.

Nora Chipaumire in portrait of myself as my father. Photo by Elise Fitte Duval.

The piece is set in a boxing ring and will be performed in at the Detroit Boxing Gym, where a program to support kids living in Detroit’s toughest neighborhoods is based and focuses on helping young black males find fruitful after-school activities to grow and develop real-life skills with positive role models.

It is not only a fitting location for Chipaumire’s exploration of black masculinity in a postcolonial world but also serves as a perfect setting for her vigorous, high-energy performance. Chipaumire has also spoken out about the brutal policing of black sexuality and masculinity, and celebrates her heritage through her art.

On Being African at the University of Michigan

African students at the University of Michigan have a unique perspective on the challenges and stereotypes Africans experience in America. Tochukwu Ndukwe, a Nigerian-American kinesiology student born in Nigeria and raised in Detroit, spoke about how his identity as a Nigerian-American student informs his experiences at the University of Michigan. In a school that is overwhelmingly white (a mere 4.4% of the population is Black or African-American), he immediately stands out.

In fourth grade, Ndukwe met a Nigerian student who embraced his culture unapologetically. This student was unafraid to educate other students about why he brought a different kind of lunch to school, or the differences between his how his parents raised him in an African household. Ndukwe was inspired by this classmate, but did not to truly publicly embrace his culture until high school. Torn between wanting to fit in with other black students and wanting to celebrate his culture in public, Ndukwe was both surprised and excited by the strength, unity, and pride of African students at the University. He now serves as president of the African Student Association (ASA), an organization that arranges cultural shows, potlucks, and mixers with other ethnic organizations on campus. Their flagship event is the African Culture Show, a massive celebration of African music and dance that packs the Power Center every year. This year’s show is titled Afrolution: Evolution of African Culture, an inquiry into the future of Africa by African students.

Ndukwe lauds African music as a crucial tether for African students to relate to the culture in their home country. He says that music allows African students to connect with their culture no matter where they are, which is especially important in Ann Arbor, which lacks the music, values, and language of their home countries.

“African music and dance are becoming more and more American,” Tochukwu says. “People there look up to America, they want to be American. African artists are beginning to collaborate with American artists, and I’m like ‘No, don’t lose your culture! It’s so rich!’” Africans are bombarded with American media and feel an increasing pressure to conform music and dance styles to that of American–particularly black American–culture, Ndukwe says.

A very loaded question

We begin discussing gender norms in Nigerian societies (he says many of the Nigerian gender norms are found throughout Africa) and a broad smile spreads across his face. “Oh, boy…you’ve asked me a very loaded question. I don’t even know where to start.”

He says, “African men are expected to be the breadwinners. They’re supposed to be strong, stoic, devoid of vulnerability. They are expected to be the disciplinarian of the family while women are expected to stay home…cook, clean, care for the children.” He explains that the expectation for men to be “macho”, and “hypermasculine” oppresses women, and that the division between genders prohibits women from getting an education and becoming financially independent.

“Mental health hasn’t even begun to be a topic in the general cultural discourse. There’s no such thing as depression, as anxiety for anyone, let alone men. So many men suffer in silence because of it.” As pressures mount for men to be sole breadwinners, disciplinarians, protectors of the family–stoic and strong–many men are subsequently unable to express their emotions with the women they care about. Ndukwe’s background as a Nigerian-born man raised by Nigerian parents tightly bound to their culture informs his relationship with women today. On a personal note, he says that he struggles to express his affection with his significant other. This leads to gaps in communication and rifts in his relationships that are often difficult to repair.

portrait of myself as my father comes at an especially important time. As the consequences of the narrow and stereotypical perception of black men enter the mainstream consciousness, this piece opens the door for discussion.

How does the representation of the black body impact the perception of self as a black woman, an African woman, and an American woman? How has colonialism seeped into the treatment of the black performing body?

Nora Chipaumire asks and investigates these questions in portrait of myself as my father.

See the performance November 17-20, 2016 at the Detroit Boxing Gym in Detroit.

Artist in Residence Spotlight: Transforming Music Notation

This post is a part of a series of posts from UMS Artists in Residence.

Simon Alexander-Adams is a Detroit-based multimedia artist, musician, and designer working within the intersection of art and technology. He has directed multimedia performances that enable connections between sonic, visual, and kinetic forms; designed new interfaces for musical expression; and produced interactive installation art. Simon’s compositions have been performed at international festivals, including the Ann Arbor Film Festival and Cinetopia.

Renegades in art are incredibly important. They remind us that our carefully constructed systems and rule books for life are just that – constructed. They can give us the jolt necessary to become aware of the patterns that enclose our perception, and if we let it, provide the space for transformative experiences.

I believe we all start life with intense curiosity, open minds, and a strong sense of exploration. In a way, it is requisite to organize the mass of sensory information that bombards us as we come into existence. Language develops and solidifies, be it spoken or sung, sonic or visual, coded, logical, emotional, or physical. We learn the rules, syntax, and conventions associated with language – and if we don’t we fail to communicate with one another. In essence, we love rules, systems and predictability.

***

When I was in middle school, I started taking cello lessons. My teacher taught using the ubiquitous “Suzuki method” that so many early string players remember (fondly or not). Yet, this was not the only method she used. She supplemented this method with fiddle tunes transposed for cello, composition assignments, and improvisational exercises, encouraging exploration simultaneously with traditional mastery of the instrument.

I remember one assignment was to create my own musical instrument, along with a corresponding notation system. I explored my house looking for objects that might be utilized to make interesting sounds. Eventually, I settled on a broken piece of a toy walkie-talkie headset, scraping it along a metal grate by our fireplace in various gestures. I then created a set of glyph’s to represent each gesture, and composed a short piece using my notation system. At the time, this seemed completely normal. Music was already notated using graphic notation (albeit a standardized one); however, there was certainly no notation I knew of to write for walkie-talkie and metal grating. It seemed paramount that one should exist.

Excerpt from Seven Systems by Simon Alexander-Adams

Fast forward 15 years or so and I find that I’m still making graphic scores .The difference is that I am more aware of the history of graphic notation – from Earle Brown, to Cornelius Cardew and Iannis Xenakis – and I let what I know of the practice inform my own. While graphic notation was definitely a renegade act in the 1950’s, I don’t see it as one at present since it has been in practice for over 60 years with countless composers making use of non-traditional notation systems. Yet, to some, graphic notation is still very much a renegade act. For those who have a rigid conception of the “rules” of musical notation and believe in a strict adherence to them, it certainly is renegade. Like many things in life, a renegade act is ascribed meaning through social and historical context – both of which differ per individual experience. In a similar way, we might unwittingly perform renegade acts as a child (disobeying authority figures, making graphic scores for household items). It isn’t until we have a concept of the rules that we can intentionally break them, and embody the spirit of a renegade. Ultimately, it becomes a question of intention and perspective.

So, why is it important that we encourage renegade musical and artistic work? I believe it is to question many of the social norms that are ingrained to the point that they have become the background of our existence. In the same way we tune out the noise of an airplane or lawnmower in the distance once it remains long enough, we are great at tuning out any pattern in life that remains constant for too long. Renegade art has the power to expose these patterns to us, allowing us to question our values, actions and way of being. Art can transform us if we let it.

Follow this blog for more from our artists in residence as they attend Renegade performances this season

Artist in Residence Spotlight: Fresh and New

This post is a part of a series of posts from UMS Artists in Residence.

This post is a part of a series of posts from UMS Artists in Residence.

Born and raised in Miami, FL, Nicole has sought a diverse musical training with the intention of exploring a limitless life through the arts. As a member of the Michigan Percussion Quartet she performed and organized an outreach tour throughout South Africa. In 2014, Nicole was a recipient of the International Institute Individual Fellowship grant, which allowed her to travel to Berlin to work alongside Tanz Tangente Dance Company.

“It’s lighter than you think.”

This tiny snippet from John Cage’s 10 Rules for Student and Teacher is one of the most valuable pieces of advice I’ve ever come across. I’m fresh out of school and feel like someone who’s just eliminated meat or gluten from her diet and finds new endless sorts of energy. Or perhaps like someone who’s started to do yoga and can turn her neck enough to look behind her and sit cross-legged without every part of her leg going numb for the first time in her life. Basically what I’m trying to say is that I’m able to approach my projects these days with freshness, excitement, and questions… and it’s THE BEST.

I’m very fortunate to have just returned from a summer working in Aspen, Colorado. Even though I grew up under the Miami sun, I’ve never spent more time outside than I did these past few months. Every day I was going on hikes beyond timberlines at 12,000 feet elevation and trying my best to take deep full breaths while looking at the never-ending mountain tops that surrounded me. I couldn’t help but smile inside and out at the natural beauty that had barely been groomed by humans. So, I guess I could say that’s a little bit about what inspires my work. I’d like my projects to feel as if they have natural beauty, with only the tiniest bit of help from humans.

Photo: Sawatch Range Just South of Aspen, Colorado. Photo by Ken Lund.

Aside from the mountains, anytime I come across mind-blowing projects, whether in person or through the Internet, these gems inspire me most. The reason I keep making work is that I hope that the happiness, inspiration, and lightness I feel when I find these projects might transfer to someone else coming across my work.

This is why I love the idea of renegade. Here’s my final tangent for this blog: When I visit my friend at his coffee shop, we always laugh the moment I step up to the counter because he knows exactly what I’m thinking: Do I order some wacky “fun drink” concoction or my go-to classic, a dirty chai. Most times, I get too excited by the prospect of finding a new favorite drink, so I end up trying something along the lines of a mocha-soy-espresso-cold-brew-n

In these prime weeks of fall, I will be visiting Pictured Rocks for the first time and hopefully catching some beautiful changing colors. I will be backpacking with friends and on the drive up, we will probably listen to the new Bon Iver album many times. I’m lucky enough to have time for a trip like this, but I urge you at least to take a walk in the beauty that surrounds us here in this magical state and try to find something new.

Follow this blog for more from our artists in residence as they attend Renegade performances this season.

Artist in Residence Spotlight: The Contrary at Michigan

This post is a part of a series of posts from UMS Artists in Residence.

This post is a part of a series of posts from UMS Artists in Residence.

Qiana Towns’s work has appeared in Harvard Review Online, Crab Orchard Review, and Reverie. A Cave Canem graduate, Towns received the 2014 Gwendolyn Brooks Poetry Prize from the Society for the Study of Midwestern Literature. She is a resident of Flint, where she serves as Community Outreach Coordinator for Bottles for the Babies, a grassroots organization created to support and educate the residents of Flint during the water crisis.

…there was one time when the Chair of the English department forbade me from showing Salvador Dali’s Un Chien Andalou in class. Guess what happened next?

I have always been what my grandmother called mouthy. The ‘yes, I heard you say no more questions, but I have another question’ type, one with a strong will and strong mind. I am like my mother—the woman who introduced me to the arts even before I exited her womb. She told me to make something of myself, so I did.

I made myself a force to be reckoned with: Woman. Bad ass. Academic. Poet. Advocate. Friend. Mother. Good girl. Artist.

Renegade.

I am drawn to art that reflects the dissimilarities in my personality, and art that exposes the oddity in every living thing. And the dead things, too.

Like macadam, all of the pieces of me fit together and are simultaneously broken. I am split into pieces and these pieces make the road that led me here, to UMS’s Renegade Artist-in-Residence program.

I first thought to myself, Renegade? At the University of Michigan? How contrary.

Just like me.

As I perused the list of shows I thought about how RENEGADE might inspire new roads and offer fresh wombs to birth work in mediums I’ve not yet explored.

I am interested in the ways humans function in different spaces as well as how personal identities contribute to individual and collective successes and failures.

Truthfully, I have a lot of questions. Each morning, I awake with a head full of questions. Poetry provides the space to consider all of the possible answers, which is not to say I am interested in the “answers.” My greatest joy is the pursuit.

Most significantly, my work is influenced by and dedicated to the marginalized and the disenfranchised. It explores the quiet corners where voiceless citizens gather to forge unbreakable bonds. I hear them. I am—on some level—them. My poems are often concerned with environments and how environs speak to the conditions of our lives and society at large. Langston Hughes’ “Mother to Son” was the first poem I ever committed to memory. I was three years old; my mother would recite the poem daily as she rehearsed for a localhttp://artists in residence stage production. Five years after she passed on, it became my mantra and the thread that bound me to her and to poetry.

Follow this blog for more from our artists in residence as they attend Renegade performances this season.

Artist in Residence Spotlight: Inspiration in the Unusual

This post is a part of a series of posts from UMS Artists in Residence. Artist in Residence Barbara Tozier works in photography with forays into video and multimedia. Born in Ohio, she settled in Michigan in 1997 after an engineering career that took her to Pennsylvania and the Netherlands. She currently works and lives in Ann Arbor. She shares her sources of inspiration in the post below.

This post is a part of a series of posts from UMS Artists in Residence. Artist in Residence Barbara Tozier works in photography with forays into video and multimedia. Born in Ohio, she settled in Michigan in 1997 after an engineering career that took her to Pennsylvania and the Netherlands. She currently works and lives in Ann Arbor. She shares her sources of inspiration in the post below.

At the skatepark. Photo Credit: Barbara Tozier, UMS 2016-17 Artist in Residence.

Inspiration comes from seeing people doing what they enjoy.

On the surface, the kickoff to the UMS Renegade series, Falling Up and Getting Down was a weird juxtaposition. While skateboarding and improvisational jazz are not usually considered analogous, they definitely are. Knowing your instrument. Knowing your tools. Knowing your capabilities, but not being limited by them. Willingness to experiment, to fall down, to play a wrong note… traditionally we’re expected to learn in private and only perform or share the “final” or “best” product of our learning. Yet improvisation is all about discovering what is “best” at the moment you’re doing the thing, and the joy of the experience. These shared traits made for a fascinating performance on a beautiful Sunday afternoon. This surprised me, as I’m not normally a fan of skating nor jazz.

It was also a perfect way for me to start this Residency. I applied because in my own work I explore genre-bending ideas, I experiment, and I like to think of new ways to approach the practice of photography. I expect that the upcoming performances in the Renegade series, such as Idiot-Syncrasy, The Encounter, and Music for 18 Musicians will also be positively surprising. I already know that these pieces speak to the notion that unusual work can be appreciated and celebrated, which is exciting to me as an artist. I’m proud that I can be a part of it and look forward to learning more.

I have a small problem, though. The plan for this post was to describe what inspires my art, and maybe could inspire you too. However, as a person without traditional art-school training (the wonderful WCC program in Photography is technical), I find it difficult to explain my work and why I make the pieces that I do. That said, I am willing to make the attempt to explain myself.

My art is about making things for me, and for exploring aspects of myself that I cannot uncover any other way. My art is about experimenting, failing, adapting, and learning. My art is about the joy of doing, exactly like the skaters enjoyed nailing those tricks.

When I’m asked “who’s your favorite photographer?” I usually respond with, “I don’t have one.” This tends to confuse people. I like looking at photographs for their aesthetic value, and as I’ve learned more about technique I can better appreciate the efforts of the photographer to make the image, but I’m not particularly interested in emulating any particular photographer. For me, inspiration comes from seeing something beautiful and wondering how I can express that beauty with photography. Inspiration comes from picking up a random bit of film and wondering what I can make with it. Inspiration comes from thinking about how to present photographs outside of a screen or a wall.

My inspiration comes from wanting to be part of the unusual, it comes from wanting to know more about how things work, it comes from within. Sometimes it comes from just sitting down and doing the work. Doing the work makes the improvisation possible.

Tune In Before Select Renegade Performances

21st Century Artist Intern Hillary Kooistra gives a pre-show Tune In for Trisha Brown Dance Company’s performance February 21, 2015.

21st Century Artist Intern Hillary Kooistra gives a pre-show Tune In for Trisha Brown Dance Company’s performance February 21, 2015.

Tune In with UMS for a brief pre-performance talk before select Renegade series performances; the next Tune In is before Bill Frisell’s solo performance on 3/12. Just 15 minutes long, each Tune In offers interesting information and provocative questions for thinking about, listening to, and watching the performance. The Renegade series celebrates artistic innovation, experimentation, and discovery.

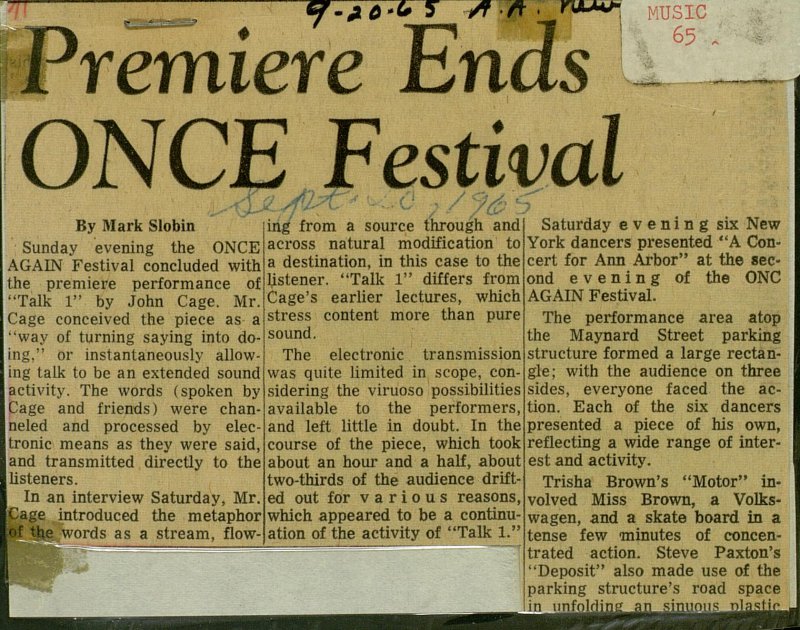

Trisha Brown’s “Motor” at 1965 ONCE Festival

50 years ago choreographer Trisha Brown revved things up with “Motor,” a choreographic work for Volkswagen Beetles that had its world premiere in Ann Arbor’s Maynard Street parking garage. Check out more about this Ann Arbor News clipping: http://bit.ly/1vKHDg0

Did you go see Trisha Brown Dance Company’s performances 2/21-22? What did you think?: http://bit.ly/1A1FhKt

eighth blackbird audience

An excited crowd waits for the eighth blackbird performance! Did you attend? Don’t forget to share your thoughts.

Curious Audiences Meet Unexpected Ideas

The UMS Renegade Series returns this season. Check out the full roster of performances on this series where curious audiences are invited to meet unexpected ideas.

Interested in more? We asked our audiences who rocked their creative worlds. Check out the submissions.

Artist Interview: Kronos Quartet’s David Harrington

Photo: Kronos Quartet, with David Harrington on left. Photo by Jay Blakesberg.

The Kronos Quartet performs two different programs in Ann Arbor on January 17-18 2014, as part of a special week of “renegade” performances also featuring saxophonist Colin Stetson.

We called up Kronos Quartet founder and violinist David Harrington to chat about his take on renegade music, how George Crumb’s epic Black Angels (which will be performed in Ann Arbor) inspired him to found the Quartet, and his take on artists who re-define instruments as Colin Stetson does.

UMS: Your performances in January are a part of a series of renegade performances this season, as part of which we’re presenting many different artists who break the rules in their own time. How do you feel about that term “renegade”?

David Harrington: Well I like it! Suits me just fine! I’ve always thought of the string quartet as offering composers, performers, and audiences a sonic glimpse into the inner world that we all participate in, and when someone does that, when they listen to their own voice, their inner voice, dramatic things happen because it’s not necessarily the voice that the society listens to and that conventional rules conform to. And so I think that the term renegade fits our music perfectly.

UMS: Is there anything about your history that strikes you as particularly “renegade”?

Since I was a little kid I felt that the art form as a whole needed a little kick in the butt. When I was growing up and I’d go to string quartet concerts—I always sat in the front row, by the way, it’s a great place to sit—

UMS: Why do you say that?

DH: Because you can see the action, you can hear the stringiness of the sound, you can see the rosin fly, and that tactility, that horse hair meets the string, the flesh meets the wood…I love that aspect of what we do. And when I go to a concert I like to be sure I can feel as much of that as possible.

But when I was growing up and going to string quartet concerts, I was always the youngest one at the show. Always. And usually concerts started with Haydn or Mozart and then usually there’d be an intermission and then Beethoven. That’s what the art form was to the general public at that point.

The Vietnam War was raging as well, and so how does one find a voice that feels real? And in August of 1973, on the radio one night, I heard Black Angels by George Crumb. And for a moment the world made sense. And I didn’t have really any choice but I had to start a group in order to play that piece.

UMS: We actually had the chance to speak with George Crumb about Black Angels and how that piece came together.

DH: Well, it was premiered at the University of Michigan.

UMS: Yes, it was! And he actually talked a bit about the way Kronos Quartet performs Black Angels, with theatricality.

I can’t imagine what it would have been like for the Stanley Quartet to get the manuscript of that piece. I wish I could have been in the room and seen their faces when they saw that.

UMS: Funnily enough, George also spoke a bit a bit how he was actually a conductor for this piece.

DH: Yes I know! He conducted the premiere.

UMS: How did you decide to approach it the way that you do?

Well first of all, I thought about the effect that the piece had on me personally. It changed my whole life. And so for me, every time we’ve ever played it I’ve been aware of its power. And I’ve hoped, all of us in Kronos have hoped to transmit that kind of visceral potentially life-altering experience.

We’ve probably played it close to 200 times, in all kinds of settings from concert halls, churches, basketball arenas, opera houses. It’s been in a lot of places.

And it took sixteen years for Kronos to record Black Angels. So we did not record it until 1989. And I’ll tell you the reason. I felt the group needed to learn more about the recording studio and how to make the sound kind of jump off the record or the CD right into the imagination of the listener.

But even more importantly, I knew that our performance of Black Angels had to be the first track on a recording. So there’s no way you could avoid it. I was hoping that listeners would basically have to confront that piece right from the very first note that they heard. It took 16 years for me to figure out what would be the second track on the album.

UMS: And how did the theatrical aspect of the live performance come to be?

When I was growing up in the early 70s, people like Pierre Boulez were saying that the string quartet was dead. Well in August of 1973 when I heard Black Angels, I knew that he was wrong. That one piece has so much power and so much presence and it requires something not only of the players, but the listeners.

Every performance that we do of Black Angels is slightly different. We’re constantly refining the way we perform the piece, and the very first time we played it is so different from the way that we do it now that you would not even recognize it. I mean, you would recognize the music of it, but you would not recognize the visual aspect of it.

And the other thing I should say about the recording is that in the recording studio you are able to have a lot of control. We followed the timings that George Crumb wrote in the score as perfectly as we possibly could and what we noticed is that Black Angels is actually a short piece. It’s very compact. It’s also not a loud piece. It has loud moments but in general it’s a very reflective piece, with these outbursts. It just so happens that it starts with an outburst.

And so that recording influenced what we wanted to do in public performance. So we didn’t set out to create a theater piece. The piece itself is theater and we just tried to make the music come alive in the best way that we could.

UMS: Colin Stetson is performing along with you as part of a week of renegade performances at UMS. Do you know his work? What do you think of his work? What makes his work stand out for you if it does?

Well, first of all, I do know Colin Stetson’s work. I’m a huge fan. It’s not often that you encounter someone who has basically redefined an instrument. And those are the people that I like to work with. And whether it’s Astor Piazzola, or it’s Tanya Tagak, the great Inuit throat singer, or Wu Man, the great Chinese pipa virtuoso, these are people who have redefined their instrument or their approach to music. I believe that Colin Stetson belongs in the same sentence. When we were on tour in New York City, I went to hear him live, and it was an amazing experience.

Curious to know more? Read our interview with George Crumb, composer of Black Angels, or explore our listening guide to Colin Stetson.

Renegade Artists in 2013-2014

Photo: From “And then, one thousand years of peace” by Ballet Preljocaj. Photo by JC Carbonne.

Artists engage daily in a creative enterprise full of risk-taking, experimentation, and boundary pushing. Renegade is about artists who, in their own time and context, draw outside the lines, changing our expectations.

Complicite & Setagaya Public Theater: Shun-kin – September 18-21

With director Simon McBurney, you can expect the full box of theatrical tools — text, music, imagery, and action — put in service to big ideas that create surprise, confusion, and disruption. The result is anything but an expected night in the theater. These are experiences which last a lifetime. (Michael Kondziolka, UMS Director of Programming) Learn more

Ballet Preljocaj – November 1-2

Dance-theater (tanztheater), a 20th-century invention primarily attributed to the German expressionists, pushed audiences’ expectations about what a dance would look like, intentionally distancing itself from the traditions of classical ballet. Its aspiration: that, through dance, all artistic media would be united and achieve an all-embracing, radical change in humankind. Angelin Preljocaj’s work lives within and expands this experimental lineage. (Michael Kondziolka, UMS Director of Programming) Learn more

Steve Lehman Octet – November 9

Composer and saxophonist Steve Lehman is trailblazing new computer-driven models for improvisation, resulting in striking new harmonies. With his Octet, Lehman has achieved the first fully realized exploration of spectral armony in the history of recorded jazz. (Mark Jacobson, UMS Senior Programming Manager) Learn more

Colin Stetson – January 15-16

Colin Stetson, who performs unbroken 10-minute-plus compositions for unaccompanied bass and alto saxophones via a combination of circular breathing, overtones, and amplified vocalizations, expands the boundaries of what was previously thought possible for solo performance. (Mark Jacobson, UMS Senior Programming Manager) Learn more

Kronos Quartet – January 17-18

For nearly 40 years, the Kronos Quartet has pursued a singular artistic vision, combining a spirit of fearless exploration with a commitment to continually re-imagine the string quartet experience. They started out as classical chamber music’s original renegades and continue that cause to this very day. Two different programs explore their take on 40 years of renegade music-making, anchored by the piece where it all began — George Crumb’s Black Angels, a highly unorthodox, Vietnam War-inspired work featuring bowed water glasses, spoken word passages, and electronic effects. (Michael Kondziolka, UMS Director of Programming) Learn more

Kremerata Baltica and Shostakovich – February 6

With Kremerata Baltica and Gidon Kremer

It is hard for any of us to imagine what it means to be denounced publicly by the highest officials of one’s own government — especially during a time when everyone pretty much understood that this kind of admonishment could lead to a life of hard labor or worse. Dmitri Shostakovich not only carried on, but continued to create a body of art that pushed right back, albeit in coded and subversive ways. As a composer, he worked within an expected tradition; as a human, he raged against all manner of censorship and injustice. Shostakovich’s Anti-formalist Gallery was a dangerously satirical cantata never intended to be published or performed, as it would have imperiled his safety. During the composer’s lifetime, the work was performed only for family and close friends; it did not receive its first public performance until January 1989, 14 years after his death. (Michael Kondziolka, UMS Director of Programming) Learn more

Who are your favorite “renegade” artists or performers? Which performances from this list are you excited to see?