Artist Interview: Petra Haden, violinist and vocalist

Photo: Petra Haden. Photo by Steven Perilloux.

Violinist and vocalist Petra Haden has been a member of groups like The Decemberists and has contributed to recordings by Beck, Foo Fighters, and Weezer, among others. With her sisters, Petra is a member of the group the Haden Triplets and will also be familiar to UMS audiences as the daughter of the legendary jazz bassist Charlie Haden.

She performs as part of guitarist Bill Frisell’s When You Wish Upon a Star group on March 13, 2014 in Ann Arbor. The two have also created recordings together.

Greg Baise is the curator of public programs at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit. This summer, Greg spoke with Petra about working with Bill Frisell, growing up in a musical family, and her interest in the nooks and crannies of film scores.

Greg Baise: This particular UMS appearance actually encompasses two evenings and is called the Bill Frisell Americana Celebration. The first evening features Bill Frisell on guitar solo. And the second evening features you as part of When You Wish Upon a Star, a relatively new band. Can you tell me more about the band and the material you’ll be working on for the concert?

Petra Haden: We’ll play from our record, the first record [Bill and I] did together. This record came to be after I played a show in Seattle with a friend of mine, and Bill came to see that show. He was interested in what I was doing, and he called me soon after to ask if we could do a record together. I was really excited to work with him because I’m such a huge fan! We decided to record a collection of our favorite songs, a variety of music from Coldplay to Stevie Wonder to Tom Waits. “When You Wish Upon a Star” was one of the songs we worked on, and our concerts together so far have been a mixture of these songs as well as Gershwin songs.

GB: In another interview you said that Bill gets your brain. What do you mean by that?

PH: It’s something that I can’t exactly put into words. It’s so hard to describe. When we play, it’s like this language that we speak together. It’s almost like he can predict where I’m going to go next. I remember hearing him when I was younger and thinking how beautiful it was, and to finally be recording with him is a dream come true.

When I was recording with Bill for my Petra Goes to the Movies album, one of the engineers told us that we seemed like brother and sister when we worked together. So, it’s also apparent to others that we’re a good match musically.

GB: I’d love to hear about the arrangement process. Do you and Bill work together to come up with arrangements for these songs?

PH: When we started working on our first record, Bill played and I sang the melody. When we were done with the basic tracks, I added violin. I just came up with stuff on the spot. I played what I heard in my head. I came up with the string ideas for songs that I’d heard, like the songs by Stevie Wonder, and also for songs like Elliott Smith’s “Satellite,” which I’d never heard before, but Bill had played for me. That’s another way he gets my brain. He told me that I had to hear this Elliott Smith song, and that became my new favorite song. He gets my taste is in music.

GB: Listening to you as you create harmonies on the record is pretty astounding. Does it come from something that you studied, or maybe from your upbringing in a musical family?

PH: I started singing with my sisters when we were really young, probably six or seven. We used to visit my dad’s family in Springfield, Missouri. They had a radio show called “The Haden Family,” and we would sit in the living room and have fun, eat, and sing together. That’s one of the first experiences I had with singing harmonies. I remember knowing at a very young age that I loved singing harmonies, and as I grew up with my sisters, we sang just for fun.

I wasn’t really active in music in high school. But later, after I graduated, I joined a band called That Dog with my sister Rachel and another high school friend. I was involved with that band for five years. I ended up going to music school at Cal Arts (California Institute for the Arts), but just for a year, so I never really had formal music training. That’s why I tend to do everything from my head, which can be hard.

GB: Has your record with your sisters, The Haden Triplets, been in the making since your childhood?

PH: Ten years ago or so we worked with a friend who wrote a few songs for us, but we weren’t recording an album at that time—it was just for fun. Any show we played, we sang these songs, and we added [the American folk group] Carter Family songs that we’d known since we were kids. But we were all busy and didn’t pursue an album, though people often asked us when we might record.

Later, we were asked to perform at a tribute show for soul and jazz poet Gil Scott-Heron, and when percussionist Joachim Cooder found out that we were a part of it, he wanted to play drums with us. He mentioned that his dad [the guitarist Ry Cooder] was interested too, so Ry played guitar with us for that show. He’s the one who called me after to say that he was interested in producing a Haden Triplets record. I was very excited because I’m a big Ry Cooder fan. We recorded it at my sister Tanya’s house before she moved in. It’s an old, big house with tall ceilings, and it was empty, so it was a great place to record.

GB: Your most recent record is Petra Goes to the Movies. I’d like to hear about your relationship to film scores in particular.

PH: I’ve always thought about doing an A Capella “Movies” album. Since I was a kid I was obsessed with all the Superman movies. I had the vinyl for the soundtracks, and I listened to them a lot and sang the string parts in my head. That was my favorite thing about going to the movies, listening to the music. Music is what tells me the story whenever I watch a movie.

GB: In the album, you’re looking at the nooks and crannies of a soundtrack that people don’t normally look at.

PH: That’s interesting that you bring that up. Often in movies, the music that I wish was on the soundtrack doesn’t ends up on it. Like in Big Night for instance, there’s a scene that just touched me, during which the owner of the restaurant with which the brothers compete plays piano. I don’t think that’s even on the soundtrack. My friend (who engineered the album) got the video and recorded it for me so that I could hear it.

Bill plays on that album too, so it’s not entirely A Capella. He thought of the theme from Tootsie, one of my favorite movies, and that’s another example of the way that he just gets my brain.

GB: Are you planning on recording another album with Bill and the When You Wish Upon a Star group that will play in Ann Arbor, or is that to be determined?

PH: That’s to be determined. I want to record with Bill for sure, but for my next record, I’m focusing on original songs. I work really well with collaborators, so I want to find the perfect writing partner.

GB: Earlier, we talked about the way you’ve admired Bill’s work for a long time. You said that to work with him is almost like a dream project. Do you have a list of other dream projects, whether that’s material or collaboration?

PH: Lately, I’ve been listening to an album by Mark Isham called Vapor Drawings. I don’t know how to get in touch with him, but he’s someone I would want to work with. I would definitely love to work with [the composer] Steve Reich, to be one of his singers. His music is another way I learned to harmonize. I love that pulsating singing so much. My other favorite guitarist is Pat Metheny. I did have the chance to work with him when I worked on my dad’s record Rambling Boy. On that record, I sing on a song that Pat plays on, which was a dream come true.

GB: Thanks for taking the time to talk! I was really excited when I saw that you would be playing in with Bill Frisell.

Curious Audiences Meet Unexpected Ideas

The UMS Renegade Series returns this season. Check out the full roster of performances on this series where curious audiences are invited to meet unexpected ideas.

Interested in more? We asked our audiences who rocked their creative worlds. Check out the submissions.

Artist Interview: Kronos Quartet’s David Harrington

Photo: Kronos Quartet, with David Harrington on left. Photo by Jay Blakesberg.

The Kronos Quartet performs two different programs in Ann Arbor on January 17-18 2014, as part of a special week of “renegade” performances also featuring saxophonist Colin Stetson.

We called up Kronos Quartet founder and violinist David Harrington to chat about his take on renegade music, how George Crumb’s epic Black Angels (which will be performed in Ann Arbor) inspired him to found the Quartet, and his take on artists who re-define instruments as Colin Stetson does.

UMS: Your performances in January are a part of a series of renegade performances this season, as part of which we’re presenting many different artists who break the rules in their own time. How do you feel about that term “renegade”?

David Harrington: Well I like it! Suits me just fine! I’ve always thought of the string quartet as offering composers, performers, and audiences a sonic glimpse into the inner world that we all participate in, and when someone does that, when they listen to their own voice, their inner voice, dramatic things happen because it’s not necessarily the voice that the society listens to and that conventional rules conform to. And so I think that the term renegade fits our music perfectly.

UMS: Is there anything about your history that strikes you as particularly “renegade”?

Since I was a little kid I felt that the art form as a whole needed a little kick in the butt. When I was growing up and I’d go to string quartet concerts—I always sat in the front row, by the way, it’s a great place to sit—

UMS: Why do you say that?

DH: Because you can see the action, you can hear the stringiness of the sound, you can see the rosin fly, and that tactility, that horse hair meets the string, the flesh meets the wood…I love that aspect of what we do. And when I go to a concert I like to be sure I can feel as much of that as possible.

But when I was growing up and going to string quartet concerts, I was always the youngest one at the show. Always. And usually concerts started with Haydn or Mozart and then usually there’d be an intermission and then Beethoven. That’s what the art form was to the general public at that point.

The Vietnam War was raging as well, and so how does one find a voice that feels real? And in August of 1973, on the radio one night, I heard Black Angels by George Crumb. And for a moment the world made sense. And I didn’t have really any choice but I had to start a group in order to play that piece.

UMS: We actually had the chance to speak with George Crumb about Black Angels and how that piece came together.

DH: Well, it was premiered at the University of Michigan.

UMS: Yes, it was! And he actually talked a bit about the way Kronos Quartet performs Black Angels, with theatricality.

I can’t imagine what it would have been like for the Stanley Quartet to get the manuscript of that piece. I wish I could have been in the room and seen their faces when they saw that.

UMS: Funnily enough, George also spoke a bit a bit how he was actually a conductor for this piece.

DH: Yes I know! He conducted the premiere.

UMS: How did you decide to approach it the way that you do?

Well first of all, I thought about the effect that the piece had on me personally. It changed my whole life. And so for me, every time we’ve ever played it I’ve been aware of its power. And I’ve hoped, all of us in Kronos have hoped to transmit that kind of visceral potentially life-altering experience.

We’ve probably played it close to 200 times, in all kinds of settings from concert halls, churches, basketball arenas, opera houses. It’s been in a lot of places.

And it took sixteen years for Kronos to record Black Angels. So we did not record it until 1989. And I’ll tell you the reason. I felt the group needed to learn more about the recording studio and how to make the sound kind of jump off the record or the CD right into the imagination of the listener.

But even more importantly, I knew that our performance of Black Angels had to be the first track on a recording. So there’s no way you could avoid it. I was hoping that listeners would basically have to confront that piece right from the very first note that they heard. It took 16 years for me to figure out what would be the second track on the album.

UMS: And how did the theatrical aspect of the live performance come to be?

When I was growing up in the early 70s, people like Pierre Boulez were saying that the string quartet was dead. Well in August of 1973 when I heard Black Angels, I knew that he was wrong. That one piece has so much power and so much presence and it requires something not only of the players, but the listeners.

Every performance that we do of Black Angels is slightly different. We’re constantly refining the way we perform the piece, and the very first time we played it is so different from the way that we do it now that you would not even recognize it. I mean, you would recognize the music of it, but you would not recognize the visual aspect of it.

And the other thing I should say about the recording is that in the recording studio you are able to have a lot of control. We followed the timings that George Crumb wrote in the score as perfectly as we possibly could and what we noticed is that Black Angels is actually a short piece. It’s very compact. It’s also not a loud piece. It has loud moments but in general it’s a very reflective piece, with these outbursts. It just so happens that it starts with an outburst.

And so that recording influenced what we wanted to do in public performance. So we didn’t set out to create a theater piece. The piece itself is theater and we just tried to make the music come alive in the best way that we could.

UMS: Colin Stetson is performing along with you as part of a week of renegade performances at UMS. Do you know his work? What do you think of his work? What makes his work stand out for you if it does?

Well, first of all, I do know Colin Stetson’s work. I’m a huge fan. It’s not often that you encounter someone who has basically redefined an instrument. And those are the people that I like to work with. And whether it’s Astor Piazzola, or it’s Tanya Tagak, the great Inuit throat singer, or Wu Man, the great Chinese pipa virtuoso, these are people who have redefined their instrument or their approach to music. I believe that Colin Stetson belongs in the same sentence. When we were on tour in New York City, I went to hear him live, and it was an amazing experience.

Curious to know more? Read our interview with George Crumb, composer of Black Angels, or explore our listening guide to Colin Stetson.

Renegade Artists in 2013-2014

Photo: From “And then, one thousand years of peace” by Ballet Preljocaj. Photo by JC Carbonne.

Artists engage daily in a creative enterprise full of risk-taking, experimentation, and boundary pushing. Renegade is about artists who, in their own time and context, draw outside the lines, changing our expectations.

Complicite & Setagaya Public Theater: Shun-kin – September 18-21

With director Simon McBurney, you can expect the full box of theatrical tools — text, music, imagery, and action — put in service to big ideas that create surprise, confusion, and disruption. The result is anything but an expected night in the theater. These are experiences which last a lifetime. (Michael Kondziolka, UMS Director of Programming) Learn more

Ballet Preljocaj – November 1-2

Dance-theater (tanztheater), a 20th-century invention primarily attributed to the German expressionists, pushed audiences’ expectations about what a dance would look like, intentionally distancing itself from the traditions of classical ballet. Its aspiration: that, through dance, all artistic media would be united and achieve an all-embracing, radical change in humankind. Angelin Preljocaj’s work lives within and expands this experimental lineage. (Michael Kondziolka, UMS Director of Programming) Learn more

Steve Lehman Octet – November 9

Composer and saxophonist Steve Lehman is trailblazing new computer-driven models for improvisation, resulting in striking new harmonies. With his Octet, Lehman has achieved the first fully realized exploration of spectral armony in the history of recorded jazz. (Mark Jacobson, UMS Senior Programming Manager) Learn more

Colin Stetson – January 15-16

Colin Stetson, who performs unbroken 10-minute-plus compositions for unaccompanied bass and alto saxophones via a combination of circular breathing, overtones, and amplified vocalizations, expands the boundaries of what was previously thought possible for solo performance. (Mark Jacobson, UMS Senior Programming Manager) Learn more

Kronos Quartet – January 17-18

For nearly 40 years, the Kronos Quartet has pursued a singular artistic vision, combining a spirit of fearless exploration with a commitment to continually re-imagine the string quartet experience. They started out as classical chamber music’s original renegades and continue that cause to this very day. Two different programs explore their take on 40 years of renegade music-making, anchored by the piece where it all began — George Crumb’s Black Angels, a highly unorthodox, Vietnam War-inspired work featuring bowed water glasses, spoken word passages, and electronic effects. (Michael Kondziolka, UMS Director of Programming) Learn more

Kremerata Baltica and Shostakovich – February 6

With Kremerata Baltica and Gidon Kremer

It is hard for any of us to imagine what it means to be denounced publicly by the highest officials of one’s own government — especially during a time when everyone pretty much understood that this kind of admonishment could lead to a life of hard labor or worse. Dmitri Shostakovich not only carried on, but continued to create a body of art that pushed right back, albeit in coded and subversive ways. As a composer, he worked within an expected tradition; as a human, he raged against all manner of censorship and injustice. Shostakovich’s Anti-formalist Gallery was a dangerously satirical cantata never intended to be published or performed, as it would have imperiled his safety. During the composer’s lifetime, the work was performed only for family and close friends; it did not receive its first public performance until January 1989, 14 years after his death. (Michael Kondziolka, UMS Director of Programming) Learn more

Who are your favorite “renegade” artists or performers? Which performances from this list are you excited to see?

Renegade Reflections – Guest Blog by Leslie Stainton

Editor’s Note: Lobby contributor Leslie Stainton will guest blog the San Francisco Symphony American Mavericks festival throughout this weekend. Read her notes on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday.

What’s next for Jeremy Denk? Definitely not Disneyland. After Sunday’s rollicking performance of Lukas Foss’s “Echoi”—a pseudo-string quartet that lent new meaning to the word “string”—the pianist was heading to Carnegie Hall, where the SF Symphony will reconfigure its Mavericks series for New York audiences this week. Denk said he and his fellow performers are bracing for a different kind of reception from the one they got here. I asked him after Sunday’s performance how he’d liked his week in A2:

Sunday’s concert drove home for me some of what the Mavericks series—and the Renegade series overall—have achieved:

- An expanded idea of what constitutes a musical instrument (Foss’s “Echoi” culminated in a dramatic thrashing of a dusty garbage-can lid) and the sounds that musical instruments—including the human voice—are capable of making. Piccolo as siren, bass fiddle as drumhead, soprano as piccolo. Our isle is indeed full of strange noises.

- A humbling appreciation of how conventional our musical tastes tend to be. Bach on the radio this weekend just didn’t do it for me. I’m sure I’ll swing back, but after the likes of David del Tredici, the Baroque seems a tad tame just now.

- Magnificent resonances—not just within the Mavericks series but within Renegade as a whole. Echoes of “Einstein on the Beach” throughout, most recently in yesterday’s vocal works by Meredith Monk and Morton Subotnick. Hints of the Hagen Quartet’s furious playing in yesterday’s Foss quartet, traces of the Tallis Scholars in Monk’s unorthodox blending of voices, and so on …

- The urgency of live performance—especially now, when we filter so much of our human experience through screens.

- The urgency of a vibrant cultural life—and the need to support it. (Thank you again, Maxine and Stuart Frankel.) Yesterday’s paper brought news of dwindling arts support in Europe. Artists and arts organizations are being asked to justify their existence by demonstrating economic impact. It’s a killer for small, weird stuff like the kind of music we’ve just spent four days absorbing, or something as mind-opening as Robert Lepage’s “Andersen Project.” And yet how vital the enterprise is to being human. I was reminded of it at last week’s American Orchestra Summit here in A2, when two bright and gifted teenagers talked about what music—hearing it, playing it, studying it—meant to their existence. This stuff saves lives, don’t kid yourself.

- The many ways that unconventional work stretches performers and audiences alike. A friend remarked to me yesterday that he’d never much liked contemporary music before, but the Mavericks series had changed him. I feel the same way. This has been a mind-expanding experience—a giant “Maverick martini,” without the hangover.

I asked a few people who’ve been closely involved with the Renegade series since its inception to reflect on the past two months—high points, low points, and everything in between:

“Stretch. That’s the word that’s come to my mind most often over the past 10 weeks, and especially in the past four days with the SFS. I love this feeling that, even when I think I’ve seen it all, something like the Renegade series stretches me in new and exciting ways as an audience member. I’ve felt myself grow, becoming more willing to tackle the ambiguous or unfamiliar, and to give myself over to these experiences in the moment. The big gift of Renegade for me is that it seems to have opened up a much more public conversation about what UMS is putting on the stage, and audiences are describing their experiences in more nuanced and complex ways (we’ve made good progress away from the like/dislike dichotomy!). With Renegade, we set upon a journey of intentional watching/listening/experiencing. It’s been interesting to see how some of us really embrace that idea, and it begins to change in new and exciting ways how we experience performance. And now that the journey has come to an end, I’m aware of how exhausting it can be to be stretched, but I’m looking forward to using this greater capacity that I’ve developed within myself and applying it to next season.”—Jim Leija, Education Director, UMS

“I was constantly on my toes. I was surprised and never knew what to expect. Just as I would sit back and say, ‘Well, yes, yes. this is going to be something I’m familiar with,’ WHAAM, something would happen to engage me/entrance me/surprise me. I am exhausted by LISTENING to all that fabulous music.”—Prue Rosenthal, Former Chair, UMS Board of Directors

“I will admit that I approached the series with some trepidation, not being sure if audiences would be receptive to the works programmed on the series. It was such a thrill on Thursday night to see the instantaneous positive response – a response that mostly continued throughout the four concerts. Not everybody liked everything, nor would I expect them to, and in all honesty, I wish more of the dissenters had posted on the Lobby also. But there was something really powerful about hearing so much modern music in a concentrated timeframe and realizing that it isn’t as scary as it looks on paper. I wish we could clone MTT, who is able to bring meaning to the pieces with just a few words about each composer. One commenter on the Lobby website was dismayed by this music being ‘ghettoized’ (my word, not the commenter’s) in one program, and thought it would be better to have it interspersed with other, more traditional works. But I’m not convinced of that. Henry Cowell in the context of Tchaikovsky or Brahms will have a decidedly different impact than when heard in the context of Varese, Ruggles, or Harrison. These concerts were a great way to introduce the idea that modern music IS accessible and enjoyable, not that it’s medicine that you need to take in order to get the Beethoven. On the whole, I was so proud of our community for embracing this festival wholeheartedly. It’s fine not to like everything – heck, I run fleeing whenever Brahms is on the program! – but the willingness to embrace the unknown was just another example of why I live in Ann Arbor.”—Sara Billmann, Director of Marketing & Communications, UMS

“What made me happiest about Mavericks and Renegades was not always knowing in advance what was going to ‘work.’ Concert programming so often presents us with an unbroken string of success stories, and that was definitely not the case with the American Mavericks’ works, several of which were ‘hot off the press.’ I was thrilled by Varèse, Cowell, Bates (of whom I’d never heard), and Foss . . . and bored by Monk and Subotnick (I don’t handle rhythmic monotony well). What was exciting in most cases, though, was not knowing what to expect. This has been an ear-freshening semester, and UMS has my sincere thanks for that.”—Steven M. Whiting, Professor, UM School of Music, Theatre and Dance; Guest Lecturer, UMS Night School

“I’ll never forget the bookends of the series — Einstein and the San Francisco American Mavericks concerts. Both were transformative to my perspective on culture in American life—watching Einstein be remounted and come into being on campus was phenomenal and gave me a rich appreciation of the work; the symphonic realization of Ives’s Concord Piano Sonata clarified my vision of the work and is still ringing in my ears. Over the course of the Renegades Series, I’ve come to see the figure of the Maverick in American culture as less of an outlaw and more of a driver of innovation, really a thought leader. That Mavericks have become a tradition in America and across the globe gives me hope that we can solve the problems that we face as a nation and world citizens. I’m certain that the Renegade Series has inspired the whole campus, faculty and students alike. Another takeaway has been the incredible value of attending shows that I don’t usually attend — for me dance and theater. UMS provides us with a rich variety of cultural experiences, and I think we as audience members need to challenge ourselves more often to attend things outside of our experience. Certainly the students in my Mavericks and Renegades class have discovered the value of expanding their cultural diet, we’ve all grown as a result.”—Mark Clague, Associate Professor of Music; Instructor, UMS Night School

Gesualdo: Rebel or Rogue? [with Audio]

On February 16, at 7:30 p.m. at St. Francis of Assisi Church, the University Musical Society presents the Tallis Scholars. This British group of about ten singers has spawned a whole industry of a cappella ensembles that aspire to sonic purity, contemplative calm, timelessness. What could the Tallis Scholars—Scholars!—possibly have to do with this season’s Pure Michigan Renegade Series, of which they are a part?

Let’s start with the gruesome facts associated with the composer at the center of the night’s program. Carlo Gesualdo (1566?–1613), the nephew of Counter Reformation enforcer Carlo Borromeo, was a prince and landholder in Venosa in southeastern Italy. Around 1588 his wife, the noblewoman Donna Maria d’Avalos, began an affair with a gentleman in the vicinity. In 1590 Gesualdo, using wooden copies of room keys he had had made, found the pair in bed together, stabbed them both, and hung their corpses in front of his castle for all to see. The story was retold repeatedly by poets of the day in a sixteenth-century equivalent of headline news.

Gesualdo, as a nobleman, was immune to prosecution, although he had plenty to fear from the relatives of his wife and her lover. He was never arrested, but he spent most of the rest of his life either on the road, investigating new musical developments, or, later on, locked up in his castle, writing music for concerts at which he himself was the audience.

The madrigals he wrote during his later years lay buried for three hundred years, but they fascinated musical modernists who unearthed them. Filled with hyper-expressive settings of texts about searing jealousy and betrayal, they seemed to push the boundaries of dissonance that was possible under the rules of Renaissance polyphony, and to anticipate music that was centuries in the future. The first performers of the madrigals, in fact, were mostly not early music specialists but the group of performers led by Robert Craft, the prominent American champion of Igor Stravinsky’s music.

Gesualdo wrote less sacred music, but the Tenebrae Reponsories (“tenebrae” means “shadows” and refers to Christian services celebrated in the days before Easter; a responsory is a setting of a text that contains an answering section) that he composed at the end of his life are among his very greatest works. In these pieces the thorny question of how Gesualdo’s life and music are related reaches an especially sharp point. Consider this setting of “O vos omnes” composed by Gesualdo in 1611, two years before his death:

“O vos omnes qui transitis per viam, attendite et videte si est dolor similis sicut dolor meus,” says the responsory text—”O you who walk down the road, pay attention and see whether there is any sorrow like my sorrow.” The text comes from the Lamentations of the Prophet Jeremiah and originally described the sack of Jerusalem in the sixth century B.C.E. It was repurposed for the Passion story. But it’s hard not to think of Gesualdo himself as the subject when the words “similis sicut dolor meus” are repeated in tonal regions unthinkably distant from the piece’s home base.

*****

Was Gesualdo really a renegade as well as a murderer? Was he even a “modernist” of his time? Some would say no — his chromaticism did not lead to a new language but only explored the strangest corners of an old one. The truly new music of the first decade of the 1600s was opera, which he did not touch. Gesualdo’s music was closed up in an emotional hothouse, and one word that’s been used to describe it is Mannerist — looked at from a certain angle, the jarring contrasts in his works were musical equivalents of El Greco’s light and shade. Or perhaps his artistic counterpart was Giuseppe Arcimboldo, the Italian who painted surreal human heads made up of vegetables, plants, and even books.

Photo: Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s Vertumnus.

What is a renegade, anyway? Does change in the arts come from an avant-garde, or does it bubble up from below? Do musical traditions tend to shock most when they begin, or when they’re coming to an end?

Whatever your ultimate answers to these questions may be, the music of Don Carlo Gesualdo has lost none of its ability to shock as it enters its fifth century of existence. If you’ve never heard Gesualdo at all, or if you know him only through the few tortured madrigals that circulate among college singing groups, hear how the language of his last years was refracted through sacred texts in the magnificent Tenebrae Responsories, somber Holy Week thoughts from a prince whose life and music intertwined in profound ways.

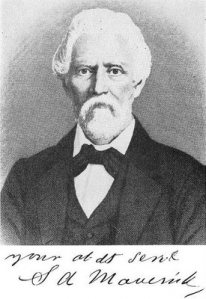

UMS Night School Report – Einstein on the Beach

On the topic of “maverick,” one of the words being used to describe the artists on offer in the Renegade series, I learned at yesterday’s first UMS “Night School” session that its primary meaning is an “unbranded calf or yearling.” The term comes from one Samuel Augustus Maverick (1803-1870), an American rancher who refused to brand his own calves so that he could claim any unbranded calf he found as his own. Needless to say, he wasn’t a popular guy in his neighborhood. More broadly, the word “maverick” refers to something—a calf, for instance, or maybe a composer—that lacks any markings of ownership. I suppose that’s what John McCain had in mind in four years ago, but I’m glad UMS is reclaiming the word for us in something like its original context, and I’m intrigued to think of artists like Robert Wilson and Olivier Messiaen (whose From the Canyons to the Stars is next up in the Renegade series) as stubborn ranchers who flat-out won’t, or can’t, brand their work.

Lots of talk at last night’s class—attended by more than 70 people—about what to expect at next week’s Einstein on the Beach. Instructor Mark Clague went over what EoB is (an opera with poetic texts, recitative, an orchestra pit, and a mythic hero) and is not (Aida). Of particular note are the work’s five-hour length and non-narrative structure, and the attendant challenges for audience members. If I leave to go to the bathroom, how will I know what I’ve missed? people wanted to know. Just how repetitive is it? I caught up with Dennis Carter, head usher for UMS, who came to last night’s class to prepare himself for next week’s event.

Inspired? What do you think it means to be a “renegade”?

Einstein as a Cultural Figure – Interview with Physicists

On Saturday, January 21, Einstein on the Beach composer Philip Glass will join a panel of special guests to ponder the cultural significance of Albert Einstein at Saturday Morning Physics. We asked guests Sean Carroll, a theoretical physicist from the California Institute of Technology who has been featured on Comedy Central’s The Colbert Report, and Michael Turner, a University of Chicago cosmology scholar who co-authored The Early Universe, a few questions.

UMS Lobby: This winter we’re presenting a series which focuses on performing arts “renegades” and examines thought-leaders, game-changers, and history-makers in the performing arts. Could you talk a bit about what it means to be a “renegade” in the sciences?

Sean Carroll: Being a renegade is very easy — being a successful renegade is very hard. In science, there are things we are quite sure are true; things that we believe are very likely to be true; and things we’re just guessing about. A successful renegade has to accept what is really true, while throwing out just those things that we mistakenly believe are true. It’s a difficult balancing act.

Lobby: How did Albert Einstein fit into this idea of ‘renegade’?

SC: Einstein was in many ways a renegade, able to discard precious beliefs that other physicists held on to; but he was also a true expert, who understood the established physics of his time as well as anyone. He had strong philosophical intuitions about how the world works, which can be a curse as well as a blessing. When the world really does line up with your intuitions, you can see further than anybody; when it doesn’t, you can find yourself wandering down a blind alley. Einstein experienced both alternatives in his career.

Michael Turner: I think it is harder to be a renegade in the hard sciences (I don’t like using the word renegade), particularly theoretical physics, since our rules are well-defined: our goal is to describe reality with mathematics, and if we are lucky to use these mathematics to make predictions about the physical world in regimes we have yet to experience. Nonetheless, there is still room for creativity and game changers, Einstein was certainly one of them. (There is an analogy here to chess, where there are fixed rules, but creativity plays a big role. I know less about music, but there are rules and there are rule-changers.) Our game changers cause us to look at the physical world in a different way, still with equations, and by doing so to achieve a deeper understanding and to predict things that haven’t been discovered yet. In Einstein’s case, he changed how we describe space, time and gravity — and of course he played a key role in helping to formulate quantum mechanics. Einstein did so in such a fundamental way that is possible to summarize his contributions in one sentence: He taught us that time warps, space is flexible and god plays dice! But he did so with equations — and his equations reduce to the old equations — Newton’s and Galileo’s — in physical situations where things move slowly and gravity is not strong. His general relativity predicts new phenomena including black holes, gravitational waves and repulsive, but it also reduces to Newton’s theory in more familiar realms (e.g., our solar system). Creativity in the world of science is constrained by what we already know and what we can learn about the physical world. I think constrained creativity is actually much more challenging and produces more interesting results.

Lobby: How has the concept of “renegade” evolved since Einstein’s time?

MT: Physics in particular and science in general has always attracted interesting characters (notice I am refusing to use the word renegade) — Dirac, Schroedinger, Feynman, Hawking to mention but a few. Thinking Different (to borrow from Steve Jobs) is often the key to a new insight or formulation. All of our game changers have had in common the ability to look at what we know and view it (or formulate it) in a new way or to ask a new question. Because science basically tells us what our place in the Universe and the rules that we have to follow, the thought leaders often attract the public’s attention. Few have achieved the stature of Einstein (Time’s Man of the Century if I remember correctly). For Einstein, there was a convergence of big paradigm shift, interesting character, and fundamental change in the center of science, with the advent of relativity and quantum mechanics, a shift from 200+ years of British domination to Europe. Then of course, Einstein helped to lead the exodus of European scientists to the US which resulted in our dominance of science over the past half century. To return to your original question, I am not sure renegade has evolved much.

SC: It is arguably more difficult to become a successful renegade now than during Einstein’s time. We know more, for one thing, but we also have a larger and more competitive scientific workplace. There is tremendous pressure on young people to produce productive work very quickly, which is very difficult if you want to buck the prevailing trends. True genius nevertheless usually wins out.

Lobby: In your view, is there an intersection between “renegades” in the humanities and the sciences? If not, what’s different? If yes, what is it?

SC: I think there is a difference, because science has a greater background of established wisdom that must be incorporated rather than overthrown. This acts as a constraint on useful forms one’s rebellion might take; Einstein invented a theory of gravity that supplanted that of Isaac Newton, but his theory had to reduce to Newton’s in an appropriate regime. So the arts and humanities have greater freedom, which can be both good and bad. Sometimes constraints are useful.

MT: I think the common theme that game changers in any creative endeavor is the ability to comprehend and understand what has come before and then re-imagine it, view it in a new way and from that to go to somewhere new. I like the way Charlie Parker put it: first you learn your sax, then you learn your music, then you just play. (Reverse the order and you just have noise.)

Lobby: Sean, as someone interested in a unified theory of time, have you gained any insights about what it means to look at such unifying questions, and especially to question such fundamental experiences as the arrow of time?

SC: Time is an interesting case, because it’s a familiar everyday concept as well as a central object in our scientific theories. As a result, even many professional physicists find it very difficult to look at how time works in its own right, without being affected by the way it is manifested in our personal experience. I have found it very useful to look at the problem from different perspectives as possible.

Lobby: Michael, As someone who focuses on the earliest moments of the universe’s creation, have you gained any insights about moments of creation or creativity in general?

MT: My experience is that moments of creativity are always unplanned and usually a surprise. They usually follow a struggle to comprehend and confusion; then pop! A new insight.

Lobby: Why were you interested in pursuing this area of research?

MT: What is wonderful about science is the diversity of ways you can contribute and how the different ways attract different people. I am a big picture guy. I like to try to understand the grand scheme. Cosmology and the birth of the Universe is a natural for me. Others, like to be able to understand every little detail how how something works — e.g., how stars evolve and explode and produce the chemical elements we are made of. Both the big picture and the small details are fascinating and important — and breakthroughs come from both.

SC: I became interested in cosmology at a very young age, about ten years old. It wasn’t until graduate school that I came to understand the connection between cosmology and the arrow of time. Once I did, I thought that this was an area that deserved more attention from working cosmologists. That’s still true!

Lobby: Michael, In one of your lectures, you discuss the “beautiful ideas” in physics, and the way most such “beautiful ideas” are not often the right ones. In fact, there is a grave yard of beautiful ideas murdered by “ugly facts” in theoretical physics. How do you think Einstein’s theories and cultural impact fit within this framework?

MT: Mathematicians and theoretical physicists are both motivated by beauty and simplicity. In physics, I believe we are motivated largely by experience: For some odd reason the rules that govern the Universe seem to be very simple and elegant, and thus we often use simplicity and beauty as a guide when exploring the unknown. But, unlike mathematics where beauty can be enough, in physics nature gets the last word: we are after all trying to find the mathematics that describes our universe, not an imaginary one more beautiful and interesting one. The most beautiful theory of cosmology was Fred Hoyle’s steady state model — but it was so simple and predictive that it was “murdered” almost instantly by hard experimental facts. Electroweak theory — the unification of the electromagnetic and weak forces which won Weinberg, Salam and Glashow a Nobel Prize — was viewed by many theoretical physicists as so inelegant that it couldn’t be correct (it is and we slowly learned to appreciate its beauty as well as look for the “grander” theory that encompasses it).

Lobby: What are some other culturally significant figures who inspire your work?

SC: I’m inspired by anyone who thinks deeply and clearly about how the world works. Galileo is an obvious hero, but for me it goes back to Lucretius, a poet and philosopher from ancient Rome. He was a naturalist and an atomist, who worked hard to understand the world in terms of matter obeying the laws of nature. We’re still working to finish his project.

—Sean Carroll is a physicist and author. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard in 1993, and is now on the faculty at the California Institute of Technology, where his research focuses on fundamental physics and cosmology. Carroll is the author of “From Eternity to Here: The Quest for the Ultimate Theory of Time,” and “Spacetime and Geometry: An Introduction to General Relativity.” He has written for Scientific American, New Scientist, The Wall Street Journal, and is a columnist for Discover magazine. He blogs at Cosmic Variance, and has been featured on television shows such as The Colbert Report, National Geographic’s Known Universe, and Through the Wormhole with Morgan Freeman.

–Michael S. Turner is a theoretical astrophysicist and the Bruce V. and Diana M. Rauner Distinguished Service Professor at the University of Chicago. He is also Director of the Kavli Institute for Cosmological Physics at Chicago, which he helped to establish. Turner was elected to the Presidential-line of the American Physical Society in 2010 and will serve as its President in 2013.

Inspired? What do you think it means to be a “renegade”?

[VIDEO] Einstein on the Beach – Original Creative Team

This winter UMS is presenting a 10-week, 10-event ‘renegade’ series focusing on thought-leaders and game-changers in the performing arts.

The opera Einstein on the Beach opens the series. Widely credited as one of the greatest artistic achievements of the 20th century, Einstein launched director Robert Wilson and composer Philip Glass to international success when it was first produced in Avignon, France in 1976.

In this video, featuring the original creative team, Philip Glass remembers the first night of Einstein, Robert Wilson sits next to Arthur Miller, and Lucinda Childs recollects the “Supermarket Speech.”

Part of Pure Michigan Renegade.

The 2012 production of Einstein on the Beach was commissioned by: University Musical Society of the University of Michigan; BAM; the Barbican, London; Cal Performances University of California, Berkeley; Luminato, Toronto Festival of Arts and Creativity; De Nederlandse Opera/The Amsterdam Music Theatre; Opéra et Orchestre National de Montpellier Languedoc-Rousillon. Produced by Pomegranate Arts, Inc.

RENEGADE Contest – Win Tickets!

This winter’s Pure Michigan Renegade series, a 10 week, 10 event series focusing on “renegades” examines thought-leaders and game-changers in the performing arts.

What’s a renegade to you? How do you know when a performing arts work or artist is truly game-changing, experimental or history-making?

Give us your answer in 7 words to enter to win tickets!

THE DETAILS

WHAT: UMS “What’s a Renegade?” Contest

REQUIREMENTS: Your definition of a performing arts renegade artist or work in exactly 7 words. This contest is free. Entries judged on creativity, renegade-ness.

DUE: January 12th, 12PM Noon.

PRIZES:

1st place: Pair of tickets to your choice of concert at San Francisco Symphony’s American Mavericks with Michael Tilson Thomas.

2nd place: 2 very special reserved seats to Robert Wilson & Philip Glass at the Michigan Theater as part of the Penny W. Stamps Speaker Series. Conversation led by acclaimed theater director Anne Bogart.

HOW TO ENTER:

(1) Tweet your entry @UMSNews

(2) Add your entry as a comment on UMS’s Facebook page during the contest period. You must label your comment as a Renegade Contest entry.

(3) Add your entry as a comment in the comments section below.

Winners to be announced by January 12th, 5PM. Questions? Ask in the comments below.

Bonus Video: Renegade composer John Cage at a game show in 1960.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?&v=7KKE0f1FGiw

Thanks to everyone who entered! Our winners, selected by UMS staff, are:

1st Place

Lesley Criscenti

Bold experimentation,

freewheeling risk,

opening minds meet.

2nd Place

Elle Bigelow

Apostate creativity

Distorting the norm

Delicious tension

Check out more of our favorites here. What was your favorite 7-word renegade definition?

UMS on Film Series

Every summer, we come up with about three dozen companion-films to the UMS main-stage season. We’ve narrowed the list to five this year – two in the fall, and three in the winter. Each expands our understanding of artists and their cultures, and reveals emotions and ideas behind the creative process.

In the fall, the films highlight deep cultural expressions which grow from communities of shared heritage. In the winter, the films tie in with UMS’s PURE MICHIGAN RENEGADE series, which focuses on artistic innovation and experimentation. We’ve created a mini film festival, Pure Michigan Renegade on Film, to extend the renegade idea and explore other artists who have created new arts frontiers.

In the fall, the films highlight deep cultural expressions which grow from communities of shared heritage. In the winter, the films tie in with UMS’s PURE MICHIGAN RENEGADE series, which focuses on artistic innovation and experimentation. We’ve created a mini film festival, Pure Michigan Renegade on Film, to extend the renegade idea and explore other artists who have created new arts frontiers.

All films (except one! see below) are presented in the U-M Museum of Art Stern Auditorium (525 S. State Street) and are free and open to the public.

Pure Michigan Renegade on Film:

Helicopter String Quartet

(1995, Frank Sheffer, 81 min.)

Wednesday, March 7, 7:00 PM at the Michigan Theater (603 E. Liberty)

Tickets: $10 general admission; $7 students/seniors/UMS and Mich Theater members; $5 AAFF members

Purchase Tickets Here

The UMS Renegade on Film series culminates at the Michigan Theatre in collaboration with the Ann Arbor Film Festival (celebrating its 50th anniversary in March 2012!!). The curators at AAFF chose an amazing documentary that captures the renegade spirit and provides a fabulous lead-in to the San Francisco Symphony American Mavericks concerts. In one of the most certifiably eccentric musical events of the late 20th century, German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen designed and executed the performance: four string quartet members playing an original piece by Stockhausen in four separate helicopters, all flying simultaneously. The sound was then routed to a central location and mixed; the work premiered, in turn, at the 1995 Holland Festival. Frank Scheffer’s film Helicopter String Quartet depicts the behind-the-scenes preparations for this event; Scheffer also conducts and films an extended conversation with Stockhausen in which the creator discusses the conception and execution of his composition and then breaks it down analytically. Featuring music by Karlheinz Stockhausen, performed by the Arditti String Quartet. Co-presented with the Ann Arbor Film Festival in partnership with the Michigan Theater, in collaboration with the U-M Museum of Art.

Past Films…

Fauborg Tremé: The Untold Story of Black New Orleans

(2008, Dawn Logsdon, 69 min.)

Tuesday, October 11, 7 pm

Connected with UMS’s presentation of A Night in Tremé: the Musical Majesty of New Orleans, this documentary follows Lolis Eric Elie, a New Orleans newspaperman on a tour of his city, a tour that becomes a reflection on the relevance of history, folded into a love letter to the storied New Orleans neighborhood, Faubourg Tremé. Arguably the oldest black neighborhood in America and the birthplace of jazz, Faubourg Tremé was home to the largest community of free black people in the Deep South during slavery, and it was also a hotbed of political ferment. In Faubourg Tremé, black and white, free and enslaved, rich and poor co-habitated, collaborated, and clashed to create America’s first Civil Rights movement and a unique American culture. Wynton Marsalis is the executive producer of the film, which also features an original jazz score by Derrick Hodge. Introducing the film is U-M American Culture faculty member Bruce Conforth, whom some may remember from last season’s series on American Roots music.

AnDa Union: From the Steppes to the City (with director Q&A)

(2011, Sophie Lascelles and Tim Pearce)

Tuesday, November 8, 7 pm

Before AnDa Union takes the stage at Hill Auditorium, filmmakers Sophie Lascelles and Tim Pearce will screen their new documentary, which follows the group of 14 musicians who all hail from the Xilingol Grassland area of Inner Mongolia. The film premieres at the London Film Festival on October 13, and Ann Arbor will be one of the first to screen it after its debut. AnDa Union is part of a musical movement that is finding inspiration in old and forgotten folk music from the nomadic herdsman cultures of Inner and Outer Mongolia, drawing on a repertoire of music that all but disappeared during China’s recent tumultuous past. Tim and Sophie will be here in Ann Arbor to introduce the film, and take audience questions after the screening.

Absolute Wilson

(2006, Katharina Otto-Bernstein, 105 min.)

Tuesday, January 10, 7 pm

Absolute Wilson chronicles the epic life, times, and creative genius of theater director Robert Wilson. More than a biography, the film is an exhilarating exploration of the transformative power of creativity – and an inspiring tale of a boy who grew up as an outsider in the American South only to become a fearless artist with a profoundly original perspective on the world. The narrative reveals the deep connections between Wilson’s childhood experiences and the haunting beauty of his monumental works, which include the theatrical sensations “Deafman Glance,” “Einstein on the Beach” and “The CIVIL WarS.”

The Legend of Leigh Bowery (with director Q&A)

(2002, Charles Atlas, 60 min.)

Monday, February 13, 7 pm

Renegade filmmaker Charles Atlas (who worked extensively with the late choreographer Merce Cunningham) introduces his 2002 documentary The Legend of Leigh Bowery. Artist/designer/performer/provocateur Leigh Bowery designed costumes and performed with the enfant terrible of British dance Michael Clark, designed one-of-a-kind outrageous costumes and creations for himself, ran one of the most outrageous clubs of the 1980s London club scene (later immortalized in Boy George’s Broadway musical “Taboo”), and was the muse of the great British painter Lucian Freud. The film includes interviews with Damien Hirst, Bella Freud, Cerith Wyn Evans, Boy George, and his widow Nicola Bowery. Charles Atlas will participate in audience Q&A immediately following the film. This film is co-presented with the U-M Institute for the Humanities which hosts Charles Atlas’s video installation “Joints Array” in February 2012.

Celebrating Mavericks

How do we innovate to make things better? What does it mean to be a maverick?

More on the themes within our 11/12 Season at Montage.