Last but not least: Pianist Sir András Schiff on Last Sonatas Project

Editor’s note: Pianist Sir András Schiff performs three concerts of the “The Last Sonatas” by Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert February 16-20, 2016. Below is his reflection on the project.

Photo: Sir András Schiff. Courtesy of the artist.

“Alle guten Dinge sind drei” — all good things are three, according to this German proverb that must have been well-known to Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert. Introducing their last three piano sonatas in three concerts — twelve works, twelve being a multiple of three — is a fascinating project that can demonstrate the connections, similarities and differences among these composers.

The sonata form

The sonata form is one of the greatest inventions in Western music, and it is inexhaustible. With our four masters of Viennese classicism it reached an unprecedented height that has never been equaled, let alone surpassed. Mozart and Beethoven were virtuoso pianists while Haydn and Schubert were not, although they both played splendidly (Schubert’s playing of his own Lieder had transported his listeners to higher spheres and brought tears to their eyes). The piano sonatas are central in their œuvres and through them we can study and observe the various stages of their development.

Lateness is relative, of course; Haydn (1733-1809) and Beethoven (1770-1827) lived long. Mozart (1756-1791) and Schubert (1797-1828) died tragically young. It’s the intensity of their lives that matters. In the final year of his life Schubert wrote the last three piano sonatas, the C Major string quintet, the song-cycle “Schwanengesang” and many other works. What more could we ask for? These last sonatas of our four composers are all works of maturity. Some of them – especially those of Haydn – are brilliant performance pieces; others (Beethoven, Schubert) are of a more intimate nature – it isalmost as if the listener were eavesdropping on a personal confession.

Lateness is relative

Both Beethoven and Schubert had worked on their final three sonatas simultaneously; they were meant to be triptychs. Similarly, Haydn’s three “London sonatas” — the only works in this series that weren’t written in Vienna — were inspired by the new sonorities and wider keyboard of the English fortepianos and belong definitely together. It would be in vain to look for a similar pattern in Mozart’s sonatas. For that let’s consider his last three symphonies — but his late music is astonishing for itsmasterful handling of counterpoint, its sense of form and proportion, its exquisite simplicity.

Let me end with a few personal thoughts. The last three Beethoven sonatas make a wonderful programme. They can beplayed together, preferably without a break. Some pianists like to perform the last three Schubert sonatas together. This, at least for me, is not a good idea. These works are enormous constructions, twice as long as those of Beethoven, and the emotional impact they create is overwhelming, almostunbearable. It is mainly for this reason that I am combining Beethoven and Schubert with Haydn and Mozart. They complement each other beautifully, in a perfect exchange of tension and release. Haydn’s originality and boldness never fail to astonish us. Who else would have dared to place an E Major movement into the middle of an E-flat Major sonata? His wonderful sense of humour and Mozart’s graceful elegance may lighten the tensions created by Beethoven’s transcendental metaphysics and Schubert’s spellbinding visions.

Great music is always greater than its performance, as Arthur Schnabel wisely said. It is never easy to listen to, but it’s well worth the effort.

Pianist Sir András Schiff performs three concerts of the “The Last Sonatas” by Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert February 16-20, 2016.

Are there artists whose “late” creativity you admire? Discuss in the comments below.

Community Spotlight: U-M Piano Professor Arthur Greene

Editor’s note: Isabel Park is a regular contributor to UMS Lobby and an undergraduate pianist in the U-M School of Music, Theatre & Dance. Isabel explores connections between the UMS season and student life.

Photo: Pianist Andras Schiff performs in Ann Arbor February 16-20, 2016. Photo by Nadia Romanini.

This winter, master pianist Sir András Schiff visits Ann Arbor for three concerts exploring the “The Last Sonatas,” later-life sonatas, of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert. He says of the sonata, that it is “one of the greatest inventions in Western music, and it is inexhaustible.”

We often view the musicians on stage as learning students or a developing performers, but, perhaps more rarely, do we think of the musicians as a teachers. Teachers can play a significant role in shaping a student’s musical style and artistic ideas. To gain some insight into the perspective of teachers and find out more about what it’s like to help younger musicians grow into independent artists, I talked to my own teacher at U-M, Arthur Greene.

Isabel Park: We’ve worked on the Beethoven Op. 109 together. Can you give an overview of the process of teaching a piece from the teacher’s perspective?

Arthur Greene: There are two sides to teaching. One is communicating and developing a conception of the work – to put it in an overly simplistic way, what the work means. The other is responding to the particular student’s way of playing and learning. With a late Beethoven sonata, our work is weighted towards the meaning of the music, because it is so particular, dense, and at first enigmatic. As far as the student’s playing, I always try to combine technical suggestions with musical ideas, based on what is working or what is not working for the student.

IP: I know this is a difficult question, but when is a piece “good enough” or ready to be performed?

AG: We had a visiting “great artist” when I was first teaching at Michigan, Eugene Istomin, to teach every few weeks. He said that in his life there were never any performances he was happy with, and usually he was very distressed after playing, because they fell so far short of perfection. I don’t think like that. When the music feels part of you, well memorized, with technical issues working 90% of the time, and if you feel you have something to say with the piece, it is ready to play.

IP: Is there anything that, say, can’t be taught to a student – or anything that you consider to be the responsibility of the student?

AG: Almost everything is the responsibility of the student. Most great teachers, such as Theodore Leschetizky, would have been unknown if they didn’t have students the caliber of Ignaz Friedman and Artur Schnabel. Teachers can inspire and guide, but the student should not rely on the teacher ultimately, or else he or she will never be an artist.

IP: What kind of a role do these classical sonatas play in the piano/classical music repertoire in general and in the repertoire of a pianist?

AG: Beethoven, Mozart, and Haydn represent the summit of the tonal system, and their sonatas are simply great music, so I can’t imagine being a pianist without playing them.

IP: For this program, Schiff is exploring the “last” sonatas of four master composers and the ways in which later-life creativity or near-death creativity was expressed for each of them. What’s your take on this programmatic structure, especially given that your work focuses on nurturing the emerging creativity of student pianists?

AG: Most composers whose works I know well develop a more subtle, complex, and personal style in their later works – Chopin, Beethoven, and Mozart for example. These are the pieces I am personally most drawn too, and I am not surprised that Schiff is as well.

IP: It’s often said that one shouldn’t say the masters until one as older (this is said humorously). What do you think about this idea?

AG: Kids might not have the last word on late Beethoven, but I’ve heard horrible performances of mature works by mature pianists as well. I like the idea of a work maturing in one’s soul for many years. Also, the idea that one must learn all the patterns of earlier music of a composer before tackling the later works is dangerous, because it fosters a paint-by-numbers way of playing. It is better to consider each pattern, phrase, and piece on its own, rather than as a meme. Overly patterned playing, and the desire to find the correct way to play something, are the reasons piano playing has become so dull.

IP: What are your favorite works to introduce to students?

AG: Chopin mazurkas. They are fascinating emotionally and rhythmically, and most of them are rarely played.

Thinking about the teaching embedded in music adds another dimension of complexity and inspiration to a performance. I’m excited to listen to pianist András Schiff’s programs with an eye for these complexities.

Sir András Schiff performs three concerts in Ann Arbor February 16-20, 2016.

Student Spotlight: Jiakung Feng, U-M student pianist

Editor’s note: Isabel Park is a regular contributor to UMS Lobby and an undergraduate pianist in the U-M School of Music, Theatre & Dance. Isabel explores connections between the UMS season and student life.

Photo: Pianist Igor Levit. By Felix Broede.

Pianist Igor Levit makes his UMS debut with a program of Beethoven, Shubert, Prokofiev, and Bach on February 6, 2016. Despite his demanding program, Levit is a relatively younger, up and coming pianist.

Much takes place behind the scenes when preparing a piece for performance, and often the audience is unaware of these aspects when listening to a performance. To get a deeper understanding of being a learner musician rather than simply a performer, I reached out to Jiakung Feng, a fellow pianist who has worked on some of the pieces on Mr. Levit’s program.

Photo: Jiakung Feng

Isabel Park: Prokofiev’s Sonata No. 7 in B-flat Major is on Mr. Levit’s program for UMS. Why did you want to learn this Prokofiev piece?

Jiakung Feng: Well, I’ve always liked Prokofiev, and I’ve played some of his other works, such as Diabolical Suggestions and The Love for Three Oranges. I also played the third sonata and wanted to play one of his later ones, so I asked my teacher and he suggested the seventh one.

IP: This is undoubtedly a difficult piece to learn. How you did you approach learning it?

JK: I found the whole sonata to be challenging to understand from a musical sense and difficult to perform from a technical perspective as well. The piece is also extremely dissonant, so just from a learning perspective, it took longer for me to actually learn all the harmonies and notes. I also listened to recordings online to listen how the great pianists interpreted this work. I especially admire Richter’s rendition.

IP: Was there a section that was memorably difficult? If so, could you describe the ways in which it was challenging? How does working through these challenges fit in with your life as a musician, and also your life outside of music?

JK: I found the sections in the first movement with jumping and cascading octaves and chords difficult to learn and play accurately. There were also uncomfortable stretches (9ths) that were taxing on my hands physically. I practiced these parts by focusing on voicing to the outsides and chunking the runs into smaller bits and then joining them together after I could play the smaller sections accurately.

I think learning a piece like this teaches one how to work through a problem, which is a good skill to have for anything. Learning something like this comes with discipline and determination.

IP: Does learning new music get easier as you learn more pieces?

JK: I think it helps to have a wide range of repertoire by a specific composer because one can begin to understand the tendencies and styles of each composer, which makes learning works by the same composer easier.

For example, if you’ve played many of the Chopin Nocturnes, you might be better accustomed to adjusting the voicing, sound, and texture in a particular way that fits that set of pieces.

IP: What sets apart the first time you perform a newly learned piece? In other words, are there any unique challenges or aspects of the experience?

JK: There’s the nerves. Even if one plays for small groups of friends as a form of practicing for performance in front of a bigger audience, there’s something different about being on stage. I becomes hypersensitive, and sometimes I might hear things that I didn’t hear while practicing. It’s hard to have continuous concentration, and in the presence of a larger audience, there’s a special atmosphere and a connection to create as well.

Photo: Igor Levit. Courtesy of the artist.

IP: Igor Levit, who’ll perform this piece with UMS, is a younger, emerging pianist (this will be his first U.S. recital tour). You are also a younger student of piano. Do you feel that where you are in your career or journey has an impact on how you study and perform?

JK: Ultimately, yes. Being a pianist in school is a lot more routine than being an independent artist. Every semester, we’re required to perform for a jury with with general guidelines, for example. As a result, there’s a specific timeline to how we prepare and goals to ensure that all the requirements are met.

Also, as students, we’re inevitably influenced a lot by our teachers’ interpretive choices. They serve as mentors and usually have direct experience with pieces that we’re learning for the first time, so in my case, my teacher’s musical ideas guide my playing quite a bit.

To me, it’s exciting to think of performance as not only a presentation but also a learning experience for the musician. I’m excited to attend pianist Igor Levit’s debut recital at UMS to witness this part of career as a pianist.

UMS Presents Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra 2/19

Learn more about the show on 2/19: http://bit.ly/1tIkfO7

Protected: Student Spotlight: U-M student Ce Sun, concerto competition winner

Student Spotlight: U-M First-year Student Isabel Park Sets Out to Explore Piano

Editor’s Note: Isabel Park is a first-year student at the University of Michigan, where she’s studying piano at the School of Music, Theatre, and Dance. This year, she’ll explore piano throughout our 2015 season, attending performances by pianist Yuja Wang and violinist Leonidas Kavakos (11/23), Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra with pianist Hélène Grimaud (2/19), Academy of St. Martin in the Fields with pianist Jeremy Denk (3/25), and pianist Richard Goode (4/26).

In the essay below, she explores her relationship with the piano. Follow her adventures and thoughts on UMS Lobby.

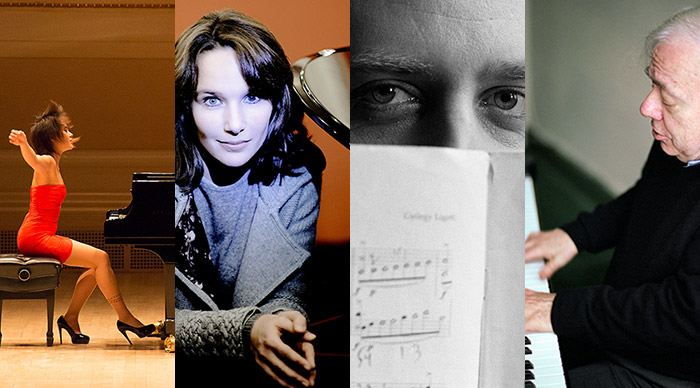

From left to right, pianists Yuja Wang, Hélène Grimaud, Jeremy Denk, and Richard Goode, all part of the 2014-2015 UMS season. Photos by Ian Douglas, Mat Hennek, and Michael Wilson.

The complexity of piano playing is astounding. Rarely do other tasks demand the intensity of full-body engagement that the piano does. Given its intricacy, piano playing can be crudely divided into technical and mental aspects; not surprisingly, a successful piano performance ultimately relies on the pianist’s adeptness in both areas, and the relative importance of each with respect to the other remains a highly disputed topic amongst pianists.

Is technique vital?

However, the relationship between a pianist’s musicianship and technical capacity is not so mutually complementary as it is often thought to be, but rather one-sidedly supplementary. Improving an aspect of one’s playing does not necessarily do the same for the other. Instead, technique supplements ability to express with a boundless sense of musicianship and musicality. Solid technique is not only a desirable, but vital to superlative piano playing that encompasses both outstanding technicality and depth of expression.

It is natural to conclude that the technical facet of piano performance is easier to approach— not necessarily easy— in the sense that improving one’s technique can be done methodically. While musicianship primarily concerns the mind, a highly equivocal part to deal with, technique mainly deals with the pianist’s physical body. The pianist can pinpoint and address specific parts of the body to enhance corresponding areas of technical facility. Not only that, technical development is easier to facilitate than musical growth because it can be measured by a universal numeric system in the form of tempi and durations, which enable objective comparisons and indications of improvement.

A unique body engagement

Yes, piano playing demands an exceptional degree of body engagement. Not only are we exercising hand-eye coordination of infinitesimal detail and precision, but the feet are also working their own set of motion. Even more uniquely, playing piano requires an unusual amount of bodily symmetry. A string player holds and draws the bow with her right hand while the left hand takes charge of fingering; similarly, a brass player manages valves with the left hand while the right hand provides support. On the piano, the hands of a pianist cover the very same keys, able even to crossover, to exchange control over different ranges, which truly gives a pianist’s hands symmetric action and equal opportunity. The bodily symmetry of piano playing also applies to the feet as they share access to the three pedals— one foot per outer pedal and a third equally distanced between the other two.

This quality of piano playing has a rather burdening implication: a pianist’s left and right hands and feet must be perfectly equivalent in terms of technical dexterity. The solution seems unrealistically simple— train each half of the body identically. Unfortunately, this proves problematic because most of us are born with dominant hands and legs that naturally possess a higher level of technical proficiency. The pianist is left with a challenge, alongside many others, of developing an artificial ambidexterity in order to master the symmetric art of piano playing.

Interestingly, piano playing is also set apart from the playing of other instruments by a factor of non-symmetry. This happens in two different, but related, respects— clefs and voices. Aside from other keyboard-natured instruments ( organ, harpsichord), the piano is the only instrument that requires the player to simultaneously read and internalize two different clefs.

A polyphonic ability

But above all, the pinnacle of piano playing and its grandeur is derived from the pianist’s polyphonic ability. Once the pianist considers the multitude of voices that he or she produces, the asymmetric factor becomes intensely complex. Although the prime examples of polyphonic music are the Bach fugues that showcase up to five voices at a time, essentially all piano music encompasses varying degrees of polyphony.

The abundance of notes is not an arbitrary flux, but rather multiple voices concurrently played. The pianist’s responsibility is to prioritize: which is the melody and which are accompaniment? He or she must voice accordingly in order to clearly and efficiently deliver the melody. The greater individuality the fingers possess, the easier this is, since the hand playing the melody is often playing an accompanying voice as well.

But the true challenge of playing polyphonic music extends beyond our fingers. The pianist’s brain must be able to process what is comparable to multiple languages to deliver a cohesive, collective body of sound. This also challenges the ears. The problem usually arises at the point of memorization. At this point, the pianist might be so accustomed to knowing the piece as the collective body of sound that she strives to produce; however, complete memory requires a detailed knowledge of each and every line of sound within the piece as well.

Being on stage

Finally, no matter how prepared, many external factors tamper with a performer’s mental condition when on stage. Performance anxiety almost always results in hyper-awareness, oversensitivity to one’s surroundings and one’s own playing, even. In many cases, the performer becomes so aware of miniscule details that perception is distorted. She could hear things within the piece that seem new or even forget the first note.

In any case, the goal is to replicate this hyper awareness in the practice room so that one simply cannot be ove-aware on stage. To combat this, isolate each sense— hearing, sight, and touch— and focus entirely on it. This level of focus is extremely difficult to maintain for prolonged periods, so dividing the movement or piece into compact sections is more productive.

Why see performances?

But given the endless ways to learn through practice and internalizing, nothing can directly replace the inspiration and teaching that transpires during a live performance. That’s why I am particularly excited to see Yuja Wang, Hélène Grimaud, Jeremy Denk, and Richard Goode live this season.

Yuja Wang has visited my hometown, San Francisco, quite a few times, and I’ve missed all of those performances. The endless mentions of her amazing technical facility and her controversial outfits have raised my curiosity as a fellow female pianist. As for Hélène Grimaud, I first heard of her through a pianist friend who raved about her live performances. Not one to praise easily, my friend has inspired me to find out first-hand what’s made her playing so extraordinary. I read Jeremy Denk‘s blog extensively, and love his very deep sense of understanding of music, something I consider quite important to good performance. On the contrary, Richard Goode remains quite a mystery to me; I know that he is part of the piano faculty at Mannes and have heard highly positive reviews of his performances. I cannot wait to see him perform live to discover what it is about him that captures those around him.

Interested in more? Follow Isabel’s thoughts and adventures here on UMS Lobby. She’ll participate in our “People are Talking!” conversations after each performance she attends.

Behind the Scenes with Yuja Wang

Piano sensation Yuja Wang (left) performs with acclaimed violinist Leonidas Kavakos (right) on November 23, 2014. Photos by Ian Douglas and Marco Borggreve.

We’re very excited for Yuja Wang’s return to Ann Arbor this November, when she’ll perform with the acclaimed Greek violinist Leonidas Kavakos. Yuja last performed in Ann Arbor in a solo recital in 2011, when we had the chance to ask her a few questions.

UMS: You’re often described as a young piano prodigy. How do you think your youth affects your performance?

Yuja Wang: If there is any effect, I think it’s unconscious or subconscious, but the pieces I learned when I was say, before 16, I would never forget, they just stick with you your whole life.

UMS: Can you talk a little about how you put together your programs? What’s your dream program?

YW: Programming is an art and I get inspired by the menus in Japanese restaurants. Variety and unity are key for me now.

UMS: What composer or work do you find most challenging to play? Do you view that as a good thing?

YW: I only play the works in public when I think I can handle it. Playing, perceiving, understanding, internalizing a work sometimes requires a lifetime, it changes when our point of view of life changes, it’s something that stays with your life, something that counts in the end.

UMS: What’s one piece of advice that you could pass on to other young aspiring musicians?

YW: Go with the flow, be creative, transcend to something more cosmic.

Did you attend Yuja Wang’s previous performances in Ann Arbor? Share your thoughts or experiences in the comments below.

This Day in UMS: Vladimir Horowitz

Editor’s Note: “This day in UMS History” is an occasional series of vignettes drawn from UMS’s historical archive. If you have a personal story or particular memory from attending the performance featured here, we’d love to hear from you in the comments.

January 31, 1930: Vladimir Horowitz in Hill Auditorium

Photos: (Left) 1930 advertisement in the Ann Arbor News (Ann Arbor News Ann Archives, Arbor District Library). (Right) Program from 1978 performance.

The great Russian pianist Vladimir Horowitz first performed in Ann Arbor on January 31, 1930, and then on another 8 occasions before 1953, when he began his long “intermission” from the concert stage. For music lovers, those years only enhanced his legend, and his return to stage in the 1970s caused a sensation.

For the inaugural concert of the hundredth season of UMS concerts in 1978, no artist could have been more fitting. Adding to the centennial pride of the local audience, the pianist was celebrating his fiftieth anniversary of his own American debut. This 1978 performance, before an enraptured audience, featured a program of works of Chopin, Rachmaninoff, and an enraptured audience found it hard to let Horowitz go, calling him back for four encores.

Behind the Scenes with Fred Hersch

This post is a part of a series of playlists curated by artists, UMS Staff, and community. Check out more music here.

Photo: Fred Hersch performs. Photo by John Rodgers.

The New York Times has praised Fred Hersch as “singular among the trailblazers of their art, a largely unsung innovator of this borderless, individualistic jazz — a jazz for the 21st century.” We’re very excited to host the Fred Hersch Trio in Ann Arbor for two different sets on January 30.

We asked Fred Hersch to recommend some of his favorite jazz pianists.

Fred Hersch: These five pianists are all heavy favorites of mine and not so well-known here in the US. John Taylor has long been Great Britain’s finest jazz pianist – and Gwilym Simcock was his student. “Sweet Dulcinea” is by British trumpeter/composer Kenny Wheeler – with whom I have had the pleasure of playing. I have collaborated with French pianist/composer Benoit Delbecq on a double–trio project “Fun House”: two pianists, two bassists, two drummers and live electronics. He is a master of prepared piano – using mostly wooden sticks of various kinds to elicit otherworldly sounds from the instrument. Bill Carrothers and Kevin Hays are mid-career American pianists whom I follow and always enjoy.

Full list:

Benoit Delbecq: “Strange Loop” from Pursuit

Kevin Hays: “Cheryl” from Live at Smalls

Bill Carrothers: “A Gerkin for Perkin” from A Night at the Village Vanguard

Gwilym Simcock: “These Are The Good Days” from Good Days at Schloss-Emau

John Taylor: Angel of the Presence (CD) Track: “Sweet Dulcinea” from Angel of the Presence

Listen on our Spotify account:

What did you think about this playlist? Share your thoughts or song suggestions in the comments below.

Interview: Charles Hamlen on Fred Hersch

Photo: Fred Hersch performs. Photo by John Rodgers.

The New York Times has praised Fred Hersch as “singular among the trailblazers of their art, a largely unsung innovator of this borderless, individualistic jazz — a jazz for the 21st century.” We’re very excited to host the Fred Hersch Trio in Ann Arbor for two different sets on January 30.

We chatted with Charles Hamlen, chairman of IMG Artists, a classical-music management company, about his personal friendship with Fred Hersch, as well as their work together with Classical Action: Performing Arts Against AIDS.

Jesse Meria (UMS): What lead to your meeting Fred?

Charles Hamlen: I met Fred for the first time around 1993. I had just started an AIDS fundraising organization called Classical Action: Performing Arts Against AIDS. I met Fred first in the the recording industry through David Chesky, who had recorded Fred on his label. And he said, you know Fred Hersch is a great pianist, he might be interested in getting involved in Classical Action.

So Fred and I met. He had been an ardent spokesperson on behalf of AIDS and HIV for years, and he has been HIV positive for more than twenty years as well as having AIDS for many years. He offered to do a benefit recording for Classical Action. It was called “Last Night When We Were Young” and that first album, which he produced but donated to classical action, raised something like $125,000, which is amazing.

Over the years he continued to produce, I think maybe a total of 5 albums for Classical Action, and for the parent company Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS, and we had a very strong relationship, and in the course of all that we became very close personal friends. I’ve been to probably dozens and dozens of his concerts

JM: Can you talk a bit more about Classical Action specifically?

CH: Classical Action is an organization that I started back in 1993. It was really in response to the AIDS crisis, and the idea was to create an organization where performing artists and colleagues professional colleagues would be able to help raise funds for AIDS service organizations around the country.

It started out as primarily artists donating their time and then the fundraising efforts grew over the years. One of the trademarks of classical action was “house concerts,” which are benefit concerts in people’s homes.

The second or third year of its existence classical action became part of the fundraising program of Broadway Cares, a nation-wide organization with the same mission. I left Classical Action myself about four years ago, but I’ve remained closely in touch with the fellow who is now directing it.

But Fred is, probably of all the people who have donated their services over the years, he is the one who has done most, performed the most often, done the most creative projects, been the most generous, but there are hundreds and hundreds of performing artists who have donated their service sin one way or another as well as opera companies and concert presenters. UMS hosted a couple of house concerts several years back in Ann Arbor.

JM: What’s significant about the Fred Hersch Trio coming to Ann Arbor? Why should we be excited about this?

CH: Well for a number of reasons. First of all, Fred is one of the pre-eminent jazz musicians in the world. In all my travels around the world, whenever I mention Fred’s name to jazz lovers, they always say, “Oh my god, he’s a genius.” Everybody feels that way, his colleagues, audience members, and so forth.

And it’s not just for jazz aficionados. One of the great treats I think is hearing someone at that level if you don’t know him, and if you don’t know the jazz world particularly well.

I think that in terms of the quality of the music, Fred’s extraordinary creativity in improvising creates a kind of magic in his performances, and there are very few people like that. He and the trio work together like hand and glove.

JM: Do you think that Fred has been made a different musician through all of his struggles? Have they made him more passionate?

CH: And it’s not just for jazz aficionados Well, I think it’s certainly made him perhaps more deeply committed than ever. I think partly, quite frankly, because he never expected to live that long. He’s gone through several severe crises in his health, and he always seems to come back stronger.

I mean you’d have to ask him this, but my impression is that when you don’t expect to be around as long as he is, and you are, you take fuller advantage of every moment in your life than other people normally would. I think also those experiences have clearly affected the depth of his music making, both his compositions and his way of communicating through music.

Listen to an audio excerpt of the phone interview:

Interested in learning more? Listen to an artist playlist curated by pianist Fred Hersch.

Goldberg Variations – A guided tour from pianist András Schiff

Editor’s Note: András Schiff performs the Goldberg Variations at Hill Auditorium on October 25, 2013. Below is his guided tour of the work.

“Se non è vero, è ben trovato.” (If it isn’t true, it’s well invented.) Johann Nikolaus Forkel, in his 1802 biography of Johann Sebastian Bach described the history of the Goldberg Variations with the following anecdote: “Count Keyserlingk, formerly Russian ambassador to Saxony, often visited Leipzig. Among his servants there was a talented young man, Johann Gottlieb Goldberg – a harpsichordist (Cembalist) who was a pupil of Wilhelm Friedemann Bach and later of Johann Sebastian Bach himself. The count had been suffering from insomnia and ill-health and Goldberg, who also lived there, had to stay in the room next door to soothe his master’s suffering with music. Once the count asked Bach to compose some keyboard pieces for Goldberg, pieces of mellowness and gaiety that would enliven his sleepless nights. Bach decided to write a set of variations, a form that prior to this, hadn’t interested him much. Nevertheless, in his masterly hands, an exemplary work of art had been born. The count was so delighted with it, he called them ‘my variations’. He would often say: ‘My dear Goldberg, play me one of my variations.’ Bach had probably never been so generously rewarded for his music. The count gave him a golden goblet with a hundred Louis d’Or!”

Se non è vero, è ben trovato.

Like all legends, this one also suffers from dubious authenticity. It is difficult to comprehend why this work, published in 1741 by Balthasar Schmid in Nürnberg, does not bear any dedication to Count Keyserlingk or Goldberg. This excludes the possibility of a commission. It is also hardly believable that Goldberg (born in 1727) would have been sufficiently developed as a musician (at the ripe old age of 14!) to handle the extraordinary musical, technical and intellectual difficulties of this composition.

However, like all legends this one also contains some elements of truth. Bach’s works in variation form are few and far between. The rare examples are the Aria variata alla maniera italiana BWV 989 (1709), the Passacaglia in C minor for organ BWV 582 (1716/17), and the Chaconne of the D minor Partita for solo violin BWV 1004 (1720). The dates show that two decades separate the Chaconne from the Goldberg Variations. He subsequently returned to this neglected genre in 1746/47 with his canonic variations on a Christmas song for organ “Vom Himmel hoch, da komm’ ich her” BWV 769.

Bach was a composer with encyclopaedic ambitions. In all the genres of sacred and secular music that he worked with, he reached heights that even to equal – let alone surpass – would be unimaginable. Had the circumstances of his life been different, and had he been court composer in Dresden, then no doubt that Johann Sebastian Bach would have become the greatest opera composer, too. In 1731 our encyclopaedist embarked on a huge project: Clavier-Übung (Clavier exercise), a collection of pieces of various styles written for different keyboard instruments. The first part (1731) contains six partitas. It represents the highest art of Baroque dance suites. The second part (1735) juxtaposes the Italian Concerto with the French Overture (not bad for a composer who had never been outside Germany). The third part is a collection of organ pieces: the Prelude and Fugue in E flat major, the Four Duets, and several chorale preludes. In the fourth and last part, Bach wanted to finish with a crowning achievement, and thus the variations provided him with a real challenge. He probably felt a certain prejudice against this form. Many of his illustrious contemporaries had produced brilliant examples that had received much applause. Bach was never interested in cheap success and his goal was to try to elevate the usually extroverted variations onto a hitherto unknown artistic and spiritual level.

The title page announces: “Clavier-Übung containing an aria with different variations for harpsichord with two manuals”. This is one of the three instances where Bach specifically calls for such an instrument (the others being the Italian Concerto and the French Overture). The theme is a beautiful aria written by Bach in 1725 for his wife in the famous Clavierbüchlein für Anna Magdalena Bach. It is symmetrically devised in two halves of sixteen bars each. Present day listeners must be careful not to be led astray by the beguiling quality of its melody, they should first concentrate on the bass line. Standing in front of a cathedral, we are overwhelmed by its size and grandeur. Our eyes are constantly diverted towards the splendour of the towers and the cupola at the top, while we tend to neglect the foundations on which the whole building rests.

This ground bass is like that of a passacaglia or a chaconne, it is the alpha and omega of the construction. There are thirty variations, after which the Aria returns in its initial shape, thus uniting the beginning with the end. Bach clearly asks the performer to repeat each section. Not doing so would destroy the perfect symmetry and its proportions. Great music is never too long. It is certain listeners’ patience that is too short.

“Aller guten Dinge sind drei” – All good things are three, thus the thirty variations are divided into ten groups of three. Each group contains a brilliant virtuoso toccata-like piece, a gentle and elegant character piece and a strictly polyphonic canon. The canons are presented in a sequence of increasing intervals, starting with the canon in unison up until the canon in ninths. In place of the canon in tenths we have a quodlibet (what pleases) which combines fragments of two folk songs with the ground bass. The tonality remains G major for the most part, with shadows of tonic minor in three variations (nos. 15, 21 & 25).

Let us go on a journey together, and let me be your guide. A guide should not talk too much, but it’s essential that she or he has already been on this trip many times, and thus can draw the passengers’ attention to the details that are relevant.

Listen to András Schiff’s recording of the Goldberg Variations on this recording and read his complete notes.

UMS’s Arts Roundup: November 12

Many members of the UMS staff keep a watchful eye on local and national media for news about artists on our season, pressing arts issues, and more. Each week, we pull together a list of interesting stories and share them with you. Welcome to UMS’s Arts Round-up, a weekly collection of arts news, including national issues, artist updates, local shout-outs, and a link or two just for fun. If you come across something interesting in your own reading, please feel free to share!

Arts Issues

- No progress made with DSO talks, so musicians travel with self-produced concert series.

- Orchestras now join the HD-broadcast performing arts trend in an effort to entice new audiences.

- Fela! musical (which appears on UMS 10/11 NT Live series) faces $5M lawsuit.

Artist Updates

- Ann Arbor resident and American opera star, Shirley Verrett, passes away at 79.

- 2011 Musical America Honorees are announced, including distinguished violinist Anne Sophie-Mutter (who has previously appeared under UMS auspices).

UMS News

- AnnArbor.com review of the Tallis Scholars’ performance at St. Francis of Assisi.

- AnnArbor.com review of Vladimir Feltsman’s piano recital in Hill Auditorium Wednesday evening.

Local Shout-Outs

- U-M musical-theater alum, Darren Criss, makes his debut as a new character on the popular TV show Glee!

- Have ideas on who should perform at Ann Arbor Summer Festival’s Top of the Park this year? Submit your ideas and your wish could be granted!

Just For Fun

- Newest member of the band? Robot musician can jam and improvise with humans!

UMS’s Arts Roundup: October 1

Many members of the UMS staff keep a watchful eye on local and national media for news about artists on our season, pressing arts issues, and more. Each week, we pull together a list of interesting stories and share them with you. Welcome to UMS’s Arts Round-up, a weekly collection of arts news, including national issues, artist updates, local shout-outs, and a link or two just for fun. If you come across something interesting in your own reading, please feel free to share!

ARTS ISSUES

- The orchestral world continues to change as Zarin Mehta steps down as President of the NY Philharmonic.

- And so does the opera world — Placido Domingo is also reducing his commitments.

- But James Levine is finally back after months of health issues that curtailed his ability to conduct.

- Arts jobs count too–NEA chief advocates the legitimacy and worth of creative jobs in the arts during hard economic times.

- Is opera worth the expense? Alex Ross voices his opinion regarding the Met’s $16 million Wagner opera cycle.

ARTIST UPDATES

- Stephen Sondheim at 80: An interview with the man who revolutionized the world of musical theater.

- Dancer/choreographer Trisha Brown featured at the Whitney Museum of American Art in program of her seminal works.

UMS NEWS

- Rosanne Cash brings superb voice and new depth to classic and new country tunes alike during her performance of “The List” at Hill Auditorium on Saturday night [review].

- Jordi Savall brings music of Spain and Mexico to St. Francis Church [review].

LOCAL SHOUT-OUTS

- Play the piano? Always wanted to try? Now’s your chance! Pull up a seat and try out any of the seven Pianos ‘Round Town, located on the sidewalks of Depot Town and Downtown Ypsilanti.

- And you can play your own melody for UMS — at intermission of the Mariinsky Orchestra and Takacs Quartet concerts (Oct. 10 and Oct. 14 respectively).

- A potential sign of hope emerges for struggling arts institutions in Michigan with the Detroit Institute of Arts likely to get $10M from the state.

JUST FOR FUN

- Once again, the hills will be alive with the sound of music, as Oprah reunites the original Sound of Music cast members.

- Dancers morph into human sculptures around Manhattan as part of the Bodies in Urban Spaces project.

UMS’s Arts Roundup: August 27

Many members of the UMS staff keep a watchful eye on local and national media for news about artists on our season, pressing arts issues, and more. We thought we’d pull together a list of interesting stories each week and share them with you. Welcome to UMS’s Arts Round-up, a weekly collection of arts news, including national issues, artist updates, local shout-outs, and a link or two just for fun. If you come across something interesting in your own reading, please feel free to share!

Arts Issues

- Pianomania puts the wishes of the world’s greatest pianists in the spotlight from the perspective of their Steinway technician

- The Wall Street Journal takes a look at how a new generation of leadership is changing the role of art museums

Artist Updates

- Just who is Grupo Corpo? Here’s a primer from UK’s The Guardian

- And now that you know them, check out a review of Grupo Corpo’s latest work, Parabelo

- In tough times, the Seattle Symphony opts for a “new” approach, commissioning 18 new works for the 10/11 season

- The New York Times reviews a new biography about Ballets Russes master Serge Diaghilev

Local Shout-Outs

- Introducing a new ballet troupe in metro Detroit – crazy talk or toast of the town?

UMS Staff Picks: pianist Rafal Blechacz selected by Susie Bozell Craig, Marketing and Corporate Partnerships Manager

SN: Although a relatively young artist, Rafal Blechacz has already established himself as a rising star in the international classical music community. How has he, at only 25 years of age, made his mark in that community and around the world?

SBC: Although he’d won several major piano competitions already, when one wins the Chopin Competition it comes with incredible opportunities. Winning the Gold Medal and all individual prizes in 2005 opened the door for him to perform at Tchaikovsky Hall in Moscow with the Mariinsky Orchestra and Valery Gergiev, at the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, Wigmore Hall in London, and the Palais des Beaux Arts in Brussels among others. It also helped secure a five-year recording contract with Deutsche Grammophon which has so far resulted in three albums, including perhaps the best recording of Chopin’s Preludes I’ve ever come across.

SN: What “flavor” does he bring to his performance that distinguishes him as such an impressive talent?

SBC: What impresses me so much about Rafal is the incredibly musical maturity he possesses. In many ways, technical prowess is the easy part. But the ability to spin phrases with perfect balance and timing, to not take too many liberties while still drawing out poignancy, the achievement of an incredibly organic result…this takes true mastery. Artists can work for years and still not achieve this.

SN: What are you most looking forward to about his upcoming Ann Arbor performance?

SBC: Chopin is one of my favorite composers for the piano, and to hear a true artist perform his works, which are so romantic with their sense of longing, nostalgia, grief…I think it will be an incredibly emotional experience.

SN: What other events are on your “must see” list for the 10/11 season?

SBC: I’m looking forward to both of the Russian orchestras, the Mariinsky and St. Petersburg, with their blockbuster programs; also Susurrus as a totally unique and intimate experience; and the two Shakespeare plays with Propeller Theater Company, both of which are new to me.

SN: What do you enjoy doing outside of work?

SBC: I’m a pretty active tennis player, and I before I started working at UMS I made a living as a flutist and still enjoy practicing and teaching. My husband and I are also looking forward to the birth of our first child late this fall.

SN: What have you been listening to on your iPod?

SBC: Well, yesterday I listened to Rachmaninoff’s second and third piano concertos in preparation for the season. I’m headed over to Lake Michigan next weekend and that always brings out summertime favorites like Jack Johnson and a quirky folk band from northern Michigan called Third Coast. It’s got a pretty wide array of artists to suit the occasion and mood.

Which pianist featured on the 10/11 season are you most looking forward to hearing?

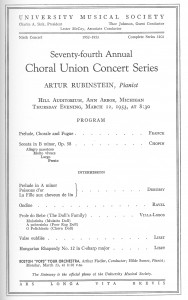

This Day in UMS History: Artur Rubinstein (March 12, 1953)

March 12, 1953

Hill Auditorium

Artur Rubinstein, pianist

There are a few musicians with whom I’d love to sit down and have a conversation. Bach, certainly, to ask him how he wrote such incredible counterpoint. Mozart, just to joke around with (although I also have a bone to pick with one of his doublings in the last movement of the D major K. 499 string quartet). Some I’d just be content to hear play: Paganini, for instance, or Joseph Joachim. Rubinstein fits into both categories: by all accounts his playing was arresting (certainly the recordings I’ve heard are), and, judging by his memoirs My Young Years, quite an entertaining companion as well.

The Arthur Rubinstein International Music Society has this to say about Rubinstein:

“Arthur Rubinstein represented in both his life and his music-making a unique joie de vivre. That alone would set him apart in this serious musical age, where there is a high degree of skill but very little charm or poetry. Arthur Rubinstein was able to communicate joy in his playing. He loved the piano, he loved the music he played, and he was always able to charm audiences all over the world with one of the most extraordinary personalities that this century has seen.

In his long life he saw interpretation pass from Romanticism to the percussionism of Bartók and Prokofiev, and then to the literalism brought in by the anti-Romantic movement, in which young pianists were trained to observe only the printed note, keeping themselves out of music. Rubinstein did not like what he heard. He realized, as all great artists do, that music means nothing until brought to life by an imaginative, sympathetic player. He knew that it was the function of the interpreter to refract the message of the composer through the prism of his own mind. Otherwise a robot could do the job as well.

Perhaps the example of his own life, and of the many great recordings he left, will spur young artists…to be their own masters, to realize that there is more to music than merely playing the notes correctly, to make music with a big mind and a big conception that not only reproduces the notes but also transcends them.”

I highly recommend reading their entire bio of Rubinstein.

Here’s the program from 1953:

Franck: Prelude, Chorale and Fugue

Chopin: Sonata in b minor, Op. 58

Debussy: Prelude in a minor; Poissons d’or; La Fille aux cheveux de lin

Ravel: Ondine

Villa-Lobos: Prole do Bebe (The Doll’s Family)

Liszt: Valse oubliée

Liszt: Hungarian Rhapsody No. 12 in C-sharp minor

“This day in UMS History” is an occasional series of vignettes drawn from UMS’s historical archive. If you have a personal story or particular memory from attending the performance featured here, we’d love to hear from you in the comments.