Einstein, Again

Some of our most exciting events during the 2011-2012 season were the preview performances of Einstein on the Beach at the Power Center in January.

Widely credited as one of the greatest artistic achievements of the 20th century, Einstein on the Beach is a rarely performed and revolutionary work that launched director Robert Wilson and composer Philip Glass to international success when it was first produced in Avignon, France in 1976, with subsequent performances in Europe and at the Metropolitan Opera. It is still recognized as one of their greatest masterpieces. This year, nearly four decades after it was first performed and 20 years since its last production, Einstein on the Beach has been reconstructed for a major international tour.

Some our staff decided to see the production again this summer at Luminato Festival. We wanted to know what it’s like to see Einstein, again.

1. What was your experience/role during the Einstein on the Beach production in Ann Arbor? Why did you decide to see the production at Luminato?

Beth Gilliland: I had the opportunity to do some “lightwalking” during the rehearsal process here in Ann Arbor. I spent many hours onstage on the spaceship, at the judges’ desk, in the courtroom, and even as Einstein – wig and all! – sitting in the “Einstein Chair” downstage right. I did get to see the entire production here in Ann Arbor, but wanted to see it again in Toronto to have a little more perspective on the show – to be more removed from the intense rehearsal process and just see it for what it is. [Ed’s Note: Beth is also our IT master at UMS!]

Jenny Graf: I manage the Ticket Office at UMS so my time (and brain) was very consumed with making sure the ticket office ran smoothly for the performances. All of the Ann Arbor performances were sold out, so that added extra stress for me. In January, I attended only the second half of the Friday preview performance. We had two other performances, but I wasn’t mentally ready to go back to one of the other performances, to sit and take it all in. However, even just seeing the second half of the production was enough to interest me. About a week later, I started regretting not seeing the whole performance. I bought a CD of Einstein and listened to it often. When the opportunity came up to see Einstein in Toronto, I jumped on it! I needed to see what I missed!

Sigal Hemy: I was an Education intern at UMS during Einstein. I wasn’t directly involved with much of the production, but I did take a few of the musicians to U-M classes. Being involved in all the build up around those classes and in the office made me really excited to see the opera in Ann Arbor. When I did see the performance here, it affected me much more than I expected. The music and the choreography were challenging, but in a way that kept me very engaged and curious. I had unanswered questions after the performance, and hoped that seeing it a second time at Luminato would let me come away with a sense of greater understanding.

2. What did you think?

BG: Interestingly enough, my mind still wandered to all the activity onstage while lightwalking – its still not possible for me to separate my personal experiences with the show from the action of merely watching the show. I guess in a certain way, everyone in the theater participates in the show at any given point – and all performances are affected by what you bring to them. Overall, though, the show has really developed – it’s much more polished – some of the music has come together beautifully with the action onstage.

JG: WOW! I was in awe. To be honest, when I heard that UMS was going to be presenting Einstein on the Beach, I was not interested in the piece. I had listened to some of the music and seen some clips and it just didn’t seem to fit my taste. I hadn’t planned on seeing the performance. In the weeks leading up to the January performances, I started getting excited about seeing Einstein. Since I thought it was more than I could handle anyway, I thought seeing just the second half would be enough to capture the experience. It only took me about a week to realize that I was wrong. I needed to see it all. June couldn’t come soon enough! I was nervous and excited to see the work in its entirety. I had decided that I was not going to leave the theater until the end unless I absolutely had to. I’m proud to say that I barely even budged in my seat because I was so captivated. It’s hard to put it into words how I felt about it. (see below) I enjoyed seeing how the production had evolved since January.

SH: The second time I saw the performance, I was able to flow with the performance, rather than being overwhelmed by the relentlessness of the work. This allowed me to take in many more of the details and assign them some sort of significance. I think in a production like Einstein, where there is so much going on, being able to anticipate anything is hugely helpful. In my case, it allowed me to catch all the detail in the lighting and in the choreography that I had missed the first time in favor of listening to the music.

3. How much did this performance stir your imagination? Overall, how strong was your emotional response to this performance?

BG: I wouldn’t say I was lost in the ‘experience’ of the show, as much as I was lost in the ‘production’ of the show, but that is likely due to my previous experience and also training in technical theater. But having seen it, you really want the people around you to enjoy it – and I found myself sometimes wanting people to pay attention to certain parts that I thought were the most brilliant, and instead there were lots of people in and out of their seats – particularly during the knee plays, which were my favorite parts. But I will say at the point after the spaceship, when the scrim depicting the atomic explosion comes in, you could hear a pin drop – it was really moving. The music and visuals had climaxed at just the right point to achieve a very emotional effect. Hair raising, chills, lump in the throat kind of effect.

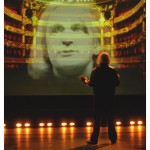

Photo: The spaceship.

JG: I had a very emotional response which was incredibly unexpected. The moment it began, I started to cry. Literally every time the music changed to a new idea, I started crying again! I was shocked at this response to the work. I’ve never been so emotionally involved in a live performance. It was all so beautifully done. One of the most beautiful moments for me was during Knee Play 4. Two of the actors are laying on glass tables and moving their bodies in interesting positions. In Ann Arbor, I was captivated by the way the lighting captured beautiful images on the backdrop of the stage that reminded me of rain water running down a window. In Toronto, Beth pointed out to me that the lighting also captured images on the backdrop of the stage below the tables that looked just like the way the actors moved their bodies in the chairs during Knee Play 2! I was blown away at that attention to detail (naturally, I cried more!). When it ended, I felt really emotionally drained. I had just witnessed something truly epic. I wonder if I’ll ever get to see it again but if I don’t, the experience I had in Toronto was amazing and I am thrilled to have been able to see it!

Knee Play 4:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=whRKj9SiHbc

SH: I think part of what made Einstein so interesting was the fact that it defied all of my expectations. As an audience member, I’m used to taking a certain amount of comfort from tropes and expectations that are always fulfilled. Einstein threw all of those things out the window, forcing me to continuously ask myself what exactly was happening. There was never a moment that my imagination was not engaged. While creating that much meaning for myself was difficult at first, I found it more and more exciting as the show went on. In fact, it was that very feeling of stirred imagination that led me to see it a second time.

4. Why do you think some arts experiences “stick”? [You remember them vividly later in life] And why don’t others “stick”? Do you think Einstein is sticky?

BG: Einstein is definitely “sticky” for me – maybe mostly due to experiencing it in Ann Arbor first – but also because it really is a “one-of-a-kind” event. Often in shows I’ve seen there are particular pieces of it that stick with you – for me a lot of them are technical aspects – or its a particular performance by a specific actor/actress/musician/dancer in the production. Its the shows that leave me feeling physically overcome at the end – emotionally drained – that I find stay with me the longest. The ones where you can’t even leave your seat when the production is over, because you’ve been that transported. And when you do finally come out of it, you find the nearest person and talk their ear off about what just happened. Einstein will probably stick with me for a long time, because of the emotional response to working on the production here in Ann Arbor, more so than the act of watching the show itself. But I certainly hope others had that same type of experience in the audience!

JG: Yes, I do think that Einstein is “sticky.” In the past few months, I have seen several UMS productions that drew my mind back to Einstein. Einstein on the Beach makes me want to slow the world down and “savor” moments more than I do. I’m not sure what makes it stick. It’s a piece that you know is from the 1970s and you can tell it’s from the 1970s yet it feels so modern at the same time. I think that the timeless qualities are part of what might make it sticky.

SH: I think that a performance sticks out in your mind when something about it is different. It could be anything from your personal circumstances on the day of the performance to the quality of the performance itself, but I think something needs to happen to prevent it from blending in with any other similar experience. In this way, Einstein is so different from any other classical performance that, for me, every single detail sticks out vividly.

5. How much did you feel a sense of connection to others in the audience?

BG: I also took the opportunity to step out in the lobby in Toronto during the performance (I watched the entire show in Ann Arbor). I was shocked at how many people were just mingling outside, some were reading, chatting, walking – it was a whole other performance just in the lobby! Fascinating opportunity to people watch, and imagine what they were thinking about the show. I didn’t talk to anyone directly, but I do remember the woman next to me in the audience would often just gasp, and say “Beautiful! Beautiful!” Most people seemed to be into it.

JG: I don’t think I really felt a direct connection with others in the audience. But I do like the notion that we shared an experience of witnessing something powerful. After the performance, many people stood outside the theater, perhaps not wanting to let go of the experience. I know that’s how I felt!

6. What questions do you still have about the production or for the directors or performers?

BG: The show is constructed in such a way that allows the audience to drift and meditate on other things outside the production, whether it be through the music or visuals or otherwise. With all the rehearsals and performances, I wonder if the performers ever get lost in the show itself – if they ever have that opportunity – or if it is too strict/technical of a performance to allow for those moments. While the experience of being in the show is I’m sure fantastic, do they feel like they’ve missed the opportunity to experience the production as so many others do? I’m also curious as to what the production is like from Jasper’s young perspective (The Boy — a child actor in the production).

JG: I wonder what the production would be like if Robert Wilson and Philip Glass weren’t directly involved in the remounting of Einstein on the Beach. Would it have the same magic if the creators weren’t putting their stamp of approval on the work? Lastly, is there going to be a new CD out of this remounting? If so, I’ll definitely add it to my collection!

Did you see Einstein in Ann Arbor, or another performance that’s”sticks” in your mind long after? What do you think makes some live performance experiences more”sticky” than others?

How to produce Einstein on the Beach

Photo: Section of a drop in Einstein on the Beach.

Photo: Section of a drop in Einstein on the Beach.

Mel Brooks’s “Producers” they’re not. “No way we’ll become become rich on this,” Linda Brumbach said yesterday at UM’s B-School in a 90-minute public conversation about the ins and outs of producing Einstein on the Beach. Brumbach is the head of Pomegranate Arts, the tiny production company that’s taken on the near-impossible task of bringing Einstein to the stage here in A2 and in 10 other venues around the world. The tour ends in Hong Kong in March 2013, and Brumbach says she’ll consider it an artistic success if “Bob, Phil, and Lucinda get the piece they want.” That’s Robert Wilson, Philip Glass, and Lucinda Childs, the artists who gave birth to the monumental opera in 1976 and have seen only two revivals since then.

After yesterday’s session, I understand why. The 1976 premiere of Einstein cost $750,000, and Wilson had to put huge chunks of that sum on his American Express card and then plead with Amex to waive interest charges. Glass had to sell the score to offset costs.

This week’s production costs a staggering $2.5 million—and that doesn’t include touring expenses. UMS President Ken Fischer said that for UMS to make money on this, “we’d have to charge $500 a ticket, and we’re not about to do that.” “I don’t think anyone can actually make money on Einstein on the Beach,” Brumbach added.

Why the exorbitant price? Consider:

• The model for Einstein’s sets costs as much as $90,000

• It takes three freight containers to ship the production

• Props include 600 pounds of dry ice

• Costumes include 30 pairs of converse high-tops

• Tech rehearsals require three solid weeks at the Power Center (the other day, Wilson spent 14 hours lighting just one scene)

• Load-in at each new venue takes three days

• Contracts for touring venues contain a 26-page technical rider

• European venues are operating in euros

• 35 press agents are needed to promote the opera worldwide

• In A2, the production requires 65 company members and 35 local stagehands

For Brumbach, the dream of producing Einstein is 12 years in the making. She first set out to revive the opera in the early 2000s, but 9/11 and its aftermath halted those plans. In 2007, it looked as though New York City Opera would partner with Pomegranate to stage the work, but the opera company’s budget was slashed and the season cancelled. A promised Paris production went nowhere. It wasn’t until UMS’s Michael Kondziolka said to Brumbach a year or two ago, “We’ll do it,” that she saw a way.

UMS is one of seven co-commissioners—three in the U.S., one in Canada, the rest overseas, and all of them “friends,” says Brumbach—who’ve gone in with Pomegranate to make this week’s historic preview performances (and subsequent tour) happen.

They’re still teching inside the Power Center as I write. One last drop is being repainted in Detroit and will be delivered to the theater at 2 pm Friday. There’s more than an element of brinksmanship to all of this. I wouldn’t want to be in Brumbach’s shoes just now, but I’m quite eager to witness her dream-come-true this weekend.

Not Quite-Live-Blogging Robert Wilson and Philip Glass Conversation at the Michigan Theatre

Editor’s Note: Last night’s Penny W. Stamps Speaker Series featured a conversation with Einstein on the Beach co-creators Philip Glass and Robert Wilson. Anne Bogart, acclaimed theater director, moderated the conversation. Leslie Stainton blogs about the event below.

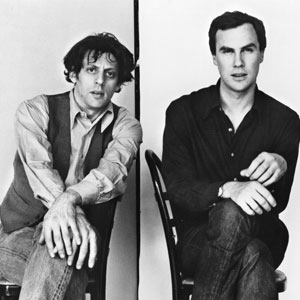

Photo: Philip Glass and Robert Wilson.

3:45 pm*

I have to ask someone to move over a seat so that there’s room for my two friends and me. The place is jammed, top to bottom. Balcony, orchestra. There’s a sound guy behind me, and a videographer up front, and dozens of people are milling about in the aisles. You’d think the Golden Globes were taking place.

*Times are approximate

4:15 pm

After a round of introductions, director Anne Bogart, who’ll moderate the conversation, takes the podium. She tells us A2 is the place to be this coming week, because we’ll get a window into the “extraordinary trajectory of this production.” She reminds us that since its inception in 1976 and its last iteration in 1992, “our lives have become faster and faster.” Einstein, she notes, “changes the time signature”—a suggestion I find beguiling.

4:20 pm

We see documentary video footage of Glass and Wilson, with snippets of the original 1976 production. Either Glass or Wilson—I can’t remember which—describes Einstein as “the god of our time.” I wonder if that holds for the 21st century?

4:30 pm

Wilson and Glass take the stage to rapturous applause. Bogart mentions the ovation. “We haven’t done anything yet,” Glass mumbles. Laughter. Surely I’m not the only one thinking, “Oh, but you have.”

4:35 pm

Wilson describes the early stages of Einstein’s development. He and Glass shared a “common sense of time and space,” he remembers. They agreed on a common megastructure and a total time length. Each man followed the same structure but filled it in different ways. This is a theme Wilson will repeat throughout today’s conversation: Form—whether of something as big as an opera or as minute as an actor’s gesture—is less important than how it is filled. Appearances to the contrary, the form of Einstein is “very classical, very formal,” Wilson says, and something we should all recognize—theme and variation.

4:40 pm

Glass observes that every time they’ve produced Einstein—in 1976, 1984, and 1992—they’ve drawn huge numbers of young audience members. Judging from the crowd in the Michigan, it’s still true.

4:50 pm

There’s talk of how radical it was in 1976 to produce an abstract work like this in a conventional setting like the Metropolitan Opera House—at a time when lofts and street theater were the rage. (Wilson remembers thinking, “What’s wrong with illusion?”) He and Glass had to rent the Met for a day in order to put on Einstein that day. “We didn’t actually have the money,” Glass interjects. Because of the opera’s five-hour duration, without intermission, the Met bars made a killing. I’m reminded that the Power Center can’t sell booze, which seems a pity.

5:00 pm

Wilson urges audiences to come and go during Einstein the way they would in a park. “It’s always going on, something is always happening.” This way, there’s “not so much difference between art and living. If you want to sit for five hours, that’s OK. If you leave in the second act and come back in the fourth, you’re not lost. It’s not like Shakespeare.” Much laughter.

Glass adds, “The audience completes the work. The piece by itself doesn’t work.”

5:10 pm

On process, both Wilson and Glass caution against knowing too much when you embark on a project. Glass: “If I know what I’m doing, then I don’t have anything to do.” Wilson: “As I got older, I learned that if I pre-decide, I often waste time, instead of going in with no idea. Let the beast talk to you instead of you talking to it.” Both say the starting point of a piece doesn’t matter. The process itself becomes the content.

5:15 pm

Glass gets a laugh when he recalls how John Cage once chided him: “Philip, too many notes.”

5:20 pm

Performer and choreographer Lucinda Childs joins the conversation. Bogart speaks of how riveting Childs’s performance in Einstein was when Bogart first saw it in 1976 and again in, I think, 1992. Bogart’s referring to the moment when Childs spends 20 mintues crossing the stage back and forth on a diagonal. For years Bogart wondered why she couldn’t take her eyes off Childs, what Childs had to teach her about the arts of acting and directing. The answer—proposed here by Wilson—seems to be that as an actress, Childs filled every single moment. He talks of the “sheer stamina” the production demands of actors, which is matched, he adds, by the stamina of watching it.

5:25 pm

Wilson unlocks something for me when he speaks of the difficulty some critics have with Einstein because it’s abstract. We can accept works by Jackson Pollock as abstract, Wilson explains, but not something we call “opera” or “theater.” Nor do conservatories or theater schools tend to include the term “abstraction” in their curricular vocabularies. Wilson says abstraction is liberating for him. This seems critical to understanding what we’re about to see onstage this week.

5:30 pm

Questions from the audience. Long lines form in both aisles. The first questioner wants to know why the opera has such short runs whenever it’s produced. Money, Glass answers. Wilson claims the same production will cost 3-4 times more to mount in New York City than in Paris. A stagehand at Carnegie Hall, he adds, makes more money than Obama.

Someone asks for advice for young artists. “Keep working,” Wilson urges. He’s not being facetious.

A stage-design student wants to know how to meld set, costume, and lighting design. Wilson notes that in conventional opera staging, sets often distract from sound, and vice versa. The question designers and directors should ask, he believes, is “How can what I am seeing make me hear better? Can I create something onstage that makes me hear the music better than I do when my eyes are closed?”

5:40 pm

In response to a long-winded and confusing question about novels and language, Wilson is more than generous. He speaks of his work with autistic children, of the difficulties that ensue when actors inject their own emotions and feelings into texts rather than letting the texts speak and audiences decipher their meaning for themselves. He says it’s “OK to get lost” when you’re reading a complicated novel or listening to a Shakespeare sonnet (or, we can infer, watching something like Einstein). “TV has changed our way of thinking. Do you understand? Do you get it?” TV is forever asking that, forever explaining. Wilson: “It’s OK to get lost.”

5:42 pm

The visual space in Einstein is organized in three very traditional ways, we learn. Portraits, still lifes, and landscapes. Bogart mentions the influence, as well, of vaudeville, and Wilson agrees, noting that Chaplin and Keaton are both inspirations.

5:45 pm

The session ends with an exchange that must warm the hearts of many in the crowd. An audience member asks why Wilson and Glass chose to reconstruct the show here in A2. Glass cites the financial practicalities of mounting a huge production like this in a noncommercial theater and mentions the educational benefits for both audience and cast, crew, and Glass and Wilson themselves.

But Wilson delivers the money quote. Ann Arbor, he says quietly, “is one of the cultural strongholds of this country.”

With that, Bogart ends the discussion and sends us out into the cold. The sun has set, the sky is a pale lavender, and the street lights are glittering. The place feels even brighter than it did two hours ago, in full daylight.

[VIDEO] Einstein on the Beach – Original Creative Team

This winter UMS is presenting a 10-week, 10-event ‘renegade’ series focusing on thought-leaders and game-changers in the performing arts.

The opera Einstein on the Beach opens the series. Widely credited as one of the greatest artistic achievements of the 20th century, Einstein launched director Robert Wilson and composer Philip Glass to international success when it was first produced in Avignon, France in 1976.

In this video, featuring the original creative team, Philip Glass remembers the first night of Einstein, Robert Wilson sits next to Arthur Miller, and Lucinda Childs recollects the “Supermarket Speech.”

Part of Pure Michigan Renegade.

The 2012 production of Einstein on the Beach was commissioned by: University Musical Society of the University of Michigan; BAM; the Barbican, London; Cal Performances University of California, Berkeley; Luminato, Toronto Festival of Arts and Creativity; De Nederlandse Opera/The Amsterdam Music Theatre; Opéra et Orchestre National de Montpellier Languedoc-Rousillon. Produced by Pomegranate Arts, Inc.

Interested in Einstein Revival? – An Anatomy of auditioning for Einstein on the Beach

Editor’s Note: Lindsay Kesselman will sing with the Phillip Glass Ensemble for the duration of the 2012-2013 international tour of Einstein on the Beach. She’ll also be guest blogging on umsLOBBY.

I don’t know about you, but I am a fan of Philip Glass. My iPod contains everything from his symphonies to his string quartets, his film scores and solo piano music, and of course, his operas. I listen to him in the car, while I’m cooking, while I’m thinking, at the gym… sometimes you are just in a Philip Glass kind of mood. So, you can understand why I briefly stopped breathing when I received an email from a new music-singing friend last March entitled, “Interested in Einstein Revival?” I wondered how quickly I could respond without sounding desperate, but then promptly ignored this concern and wrote back, um…yes. I was interested.

As a singer, I’m usually fairly zen about auditions. Many variables are out of our control, so I try to be prepared, do my best work, but spend as little time obsessing about it as possible. I pretend I don’t care about the outcome, and tell myself that I will be successful regardless of whether or not I get the part.

The truth was, however, that this time I did care, and no amount of denial-ridden inner monologue would convince me otherwise. I sent in a resume and samples of my singing and then tried to preserve my outer calm while I waited. I didn’t have to wait long before being invited to come to New York in early May to audition at the Baryshnikov Arts Center for a chorus role.

Being part of Einstein on the Beach was beginning to become a real possibility, so I let myself get a little bit excited. I started listening to sections of the piece and I watched a wonderful documentary on the making of Einstein entitled “Einstein on the Beach: The Changing Image of Opera” which, as a side note, I would recommend highly to anyone as a fascinating introduction to the piece, or as a way to learn more for those that are already familiar with it. (All the members of my family “might” be receiving this documentary for Christmas this year.)

I also started practicing, both the piece I had decided to sing for the audition, as well as exercises I drew from Einstein. The text of the opera is comprised of numbers and solfege syllables, sometimes sung very rapidly and in constantly-changing rhythmic meters. I figured that if by some chance I was cast, I would need to start practicing immediately so I would not become hopelessly tongue-tied in rehearsals.

So, I auditioned in NYC for Lisa Bielawa, Michael Riesman, and Linda Brumbach. I was the first to sing that day (we were asked to prepare something in English), and then Michael Riesman asked me to say aloud 1 2 3 4, 1 2 3, 1 2 3 4 1 2 3, etc as quickly as possible. Aha!! My compulsive practicing of numbers had paid off. The audition was over before I knew it, and I flew home to wait again, with ever-building excitement and anticipation.

Fortune smiled, and I was invited to a callback audition three weeks later, this time to sing excerpts from Einstein, the choruses “Night Train” and “Spaceship,” as well as to complete a movement/dance audition. I arrived at the DANY Studios along with 24 other singers, all vying for 12 spots (3 of each voice type). Everyone knew each other, greeted each other warmly, with hugs, like at a big family reunion. I remember thinking about how COMPLETELY different this was from any other audition I’d ever done, and I’d hoped I’d have the opportunity to become part of this strange and wonderfully supportive community.

We were divided in half, and when it was our turn, we filed into a dance studio and faced a long table. There were many important people in the room, including a camera crew for an upcoming documentary, but I found myself staring directly at Robert Wilson. I knew what he looked like and had known he would be there, but as soon as I saw him, various highlights from his staggeringly impressive bio began running through my brain like ticker-tape, and I was stunned. I took a deep breath and decided I could be star-struck later: now was the time to focus.

We sang through the prepared sections up to tempo, I was asked to jump up to a descant line above the choir, and I started feeling pretty good. This wasn’t so bad, I thought. Then, we were divided in half again for the dance audition. Ever since the callback invitation, I tried to psych myself up for this part, but let’s be clear: I am not a dancer by any stretch of the imagination. We started off easily enough, with some focus and posture exercises. Then, Wilson asked us to cross the room, but to take at least 3 minutes to do so (very, very slowly) and, not allowing the initiation point of our movements to be seen. A fascinating challenge, one that required us to spend at least the first 30 seconds to transfer our weight to one foot.

Then, my moment of truth came. Robert Wilson left his place at the table to demonstrate a “routine” for us, which we were to instantly memorize and then re-create. As we watched, our collective adrenaline turned quickly to collective dread as the slow, stylized movement of the routine kept going… and going. Silently, I cursed my 10-year-old self for not continuing with ballet. I thought, “Well, that’s it. This was fun, but my lack of dance training will cost me this job.” No one moved a muscle when Wilson told us it was our turn. Then, slowly we forced our legs back to our positions and made the routine up the best we could, mimicking the style of the movement, if not its exact steps.

Ultimately, a miracle happened, and, a few days later, I got the invitation to join the tour. Now, months later, I am still giddy with excitement at the adventure that is about to begin. As I become familiar with each segment of my 85 page score, which will eventually expand into 4 ½ hour show, I know that in a matter of weeks, I will be singing this music in my sleep and it will become a part of who I am for the next 13 months.

My voice teacher in graduate school always told me that my path would be different, that it would probably be somewhat non-traditional, but that I would find my way. This year that path has led me to Philip Glass and Einstein on the Beach and I truly could not be more grateful.

Have a question for Lindsay, or curious about something to do with Einstein on the Beach? Use the hashtag #askeinstein on Twitter or comment below.

Einstein on the Beach: Q&A with Lindsay Kesselman

Widely credited as one of the greatest artistic achievements of the 20th century, Einstein on the Beach is a rarely performed and revolutionary work that launched director Robert Wilson and composer Philip Glass to international success when it was first produced in Avignon, France in 1976, with subsequent performances in Europe and at the Metropolitan Opera. It is still recognized as one of their greatest masterpieces. Now, nearly four decades after it was first performed and 20 years since its last production, Einstein on the Beach will be reconstructed for a major international tour, including the first North American presentations ever held outside of New York City.

Widely credited as one of the greatest artistic achievements of the 20th century, Einstein on the Beach is a rarely performed and revolutionary work that launched director Robert Wilson and composer Philip Glass to international success when it was first produced in Avignon, France in 1976, with subsequent performances in Europe and at the Metropolitan Opera. It is still recognized as one of their greatest masterpieces. Now, nearly four decades after it was first performed and 20 years since its last production, Einstein on the Beach will be reconstructed for a major international tour, including the first North American presentations ever held outside of New York City.

Prior to the production’s final technical rehearsals and world première in Montpelier, France, UMS will host the production’s creators, musicians, performers, and crew for three weeks as they reconstruct and rehearse the work for what is likely to be the final world tour designed and led by its original creative team. A rare chance to see a work of this scale in progress, these preview performances will be the only opportunity to see Einstein on the Beach in the Midwest.

Lindsay Kesselman will sing with the Phillip Glass Ensemble for the duration of the opera’s 2012-2013 international tour. She’ll also be guest blogging on umsLOBBY.

UMS: As an emerging artist, how do you approach a seminal work like Einstein on the Beach?

Lindsay Kesselman: With great humility….and tons of excitement! I remember hearing about Einstein on the Beach for the first time as a freshman in my undergraduate music history class. Even then, I remember thinking that this was my kind of opera, and exactly the sort of piece I hoped to sing one day. Now, being given the chance to participate in a re-creation of this incredible work, and in a production of this size and scope, is nothing short of thrilling.

UMS: You studied at voice at Michigan State University and have Michigan roots. Does beginning with this production in Michigan hold any special importance for you?

LK: Definitely. I received a B.M. in voice and music education from Michigan State University in 2006 and, after spending a few years away, returned to live in Ann Arbor 2 years ago. I regularly attend UMS events, and feel so fortunate that we will have the opportunity to workshop the piece and give preview performances here at the Power Center. This is a wonderfully vibrant community, filled with people who are curious and interested in a diverse array of arts, and I am so excited that they will have the chance to see this production first. For me personally, it will be wonderful to share this experience with my local family and friends, and it will be a luxury to be home during the month of January!

UMS: What are you most looking forward to during this production? What do you hope to learn from your work on this production?

LK: There are so many things to which I am looking forward…the chance to learn from the extraordinary visionaries and creators of this piece, Philip Glass, Robert Wilson and Lucinda Childs, will be a once-in-a-lifetime privilege. Learning from and growing with the remarkable members of the Philip Glass Ensemble, my fellow singers, and the entire cast and crew, will be life-changing. And certainly, having the chance to introduce this piece to a new generation of audiences across the world will be humbling and truly unforgettable.

Have a question for Lindsay, or curious about something to do with Einstein on the Beach? Use the hashtag #askeinstein on Twitter or comment below.

Renegade Series will shake up your mud months

Some renegades: 1. Einstein on the Beach and 2. Random Dance.

A friend from Minneapolis was visiting earlier this summer, and we got to talking about the dreaded “mud months” up here in the icy north—February, March, alas, even April. Our friend mentioned that she’d spent a week in Arizona last February, but when I said I envied her, she shook her head. “Actually,” she said, “I cut my trip short. I couldn’t wait to get back.”

“What made you do that?”

The cultural life, she said. “There’s no cultural life down there.”

With apologies to the Heard Museum and Ballet Arizona, I think she’s got a point. And I’ve promised myself that this year, no matter how bad it gets, I’m not going to complain when it’s mid-March and I’m shoveling snow for the third time in a week, because the cultural offerings in Ann Arbor more than compensate. (Of course nothing about winter seems bad right now, so long as there are no mosquitoes.)

I’m actually looking forward to the mud months of 2012, because that’s when UMS—in what’s either a brilliant move or a potentially ruinous gesture of faith in the weather gods—is presenting its Renegade series. For me it’s the most tantalizing thing on offer this season, and I’ll be tracking it here on the Lobby, hoping to answer some of the questions I’ve long had about the process of art and art-making, and what makes some artists true outposts of genius and others mere followers. The series starts in January with a reconstruction of the 1976 opera Einstein on the Beach and winds up in late March with the San Francisco Symphony’s “American Mavericks” series, and in between covers a wide and intriguing arc of genres and eras. Beethoven, Gesualdo, Robert Lepage, Jessye Norman, Meredith Monk, Robert Wilson, Philip Glass—they’re all part of it, and they’ll all be here, in spirit or person, as we hunker down under Michigan’s gray skies and count the days until the crocuses bloom.

Because he has as much to do with the evolution of this series as anyone on the planet, I’m starting my personal Renegade “journey” with UMS Programming Director Michael Kondziolka:

LS: What’s the genesis of the Renegade series?

MK: I’ve been having a conversation for 10 years about Einstein on the Beach. And I was also having a conversation with the San Francisco Symphony about a remount of their American Mavericks festival—the first one they did was 10 years ago, in San Francisco. Both of these conversations were long-term and ongoing. And there was a moment when I realized, “Huh! It appears that both of these projects are going to land in the same season.” And when I realized that, I started thinking about the commonalities.

The American Mavericks festival is really all about Michael Tilson Thomas’s vision for a certain kind of American sensibility and “mavericky-ness” when it comes to orchestral music composition—what it means to be American, and what it means to be an innovator and an experimenter. And how can that not in some way relate to Einstein on the Beach, which is, of course, an American work of music, theater, or opera that very much embodied those same ideas of risk-taking, innovation, scale, in creating something really new.

That, strangely enough, collided with another moment that I had last season, where I’m sitting there listening to Pierre Boulez talk about his life, his ruminations on the 20th century, and his role in that. And a student asked a really wonderful question about what the new electronically based media means for music and composition. And Boulez said, “Je ne suis pas un prophète.” “I’m not a prophet. ” And he started to expound on artistic works that are truly important, that are game-changers—works we could never, ever have possibly anticipated, and once we’ve experienced them, could never imagine living without. This was his definition for something that’s truly important.

And I guess it was that statement from such an important intellectual, about art and culture, and these two projects that were long-term conversations, coming together and forming the possibility of a thread of performances devoted to this idea of work that really has changed the direction of the form.

LS: I like the term “game-changers.”

MK: It also felt very zeitgeisty to me. That these things came together at a time when our popular discourse, and our popular political discourse, is just polluted with vocabulary about innovation. “Innovating our way out of the difficulties that we face today.” “Being a maverick.” “I’m the real maverick.” All of this bullsh!t that’s kind of like wallpaper, but there’s no real there there. And of course there are lots of examples of real mavericks, of people who are really innovating, but it also seems kind of … cheap. We’re cheapening the meaning of some of these ideas, of what it means to be a real change-agent.

LS: Why “renegade”?

MK: Ultimately we wanted to choose a word that hasn’t been overused, a word that maybe made people feel both a little bit curious and a little bit uncomfortable. I like the word, because it toggles between the artists, their artistic output, and the audience. What does it mean if you’re an audience member who chooses to go to these sorts of events? Are you a little bit of a renegade? Are you taking a risk? How do you feel about taking that risk, and what do you get out of taking that risk? As consumers of the arts—as listeners and observers—it is the moments when we take risks, or step into something that we have no idea what it is, and are completely bowled over and changed, that matter. Period.

LS: In an ideal world, what do you hope audiences might take away from this?

MK: In a dream world, I want the takeaway to be something really simple. I want people to leave the experience with some sense of that quality of innovation, or change-agency, or specialness, that defines the work as part of this series.

LS: You start with a bang—Einstein on the Beach—and end with another bang, the San Francisco Symphony’s Mavericks series. So how did you decide to flesh out the middle?

MK: How did I want to fill in that time between those two bookends (which is what we’re calling them)? The one thing that was really important to me was that it not focus only on work of the last 50 years. I didn’t want this to feel like a quote-unquote contemporary music series. I wanted to tell a much larger story about moments of extreme change. So I asked Peter Phillips of the Tallis Scholars to put together a Renaissance mavericks program. And we’ve included the Hagen String Quartet’s all-Beethoven concert as a wonderful way of creating an opportunity to understand how Beethoven really changed classical music aesthetics. That’s an obvious concert to include in a series like this. I think Beethoven’s the ultimate maverick.

LS: Beyond just having an interesting cultural experience, and coming away saying, “Wow, I was there for that,” does a series like this have the potential to change our culture by changing the audience? In the best of all possible worlds, how might this shake people up? What might they get from this that goes beyond just the bragging rights, and the curiosity factor?

MK: Obviously, if entering into an unexpected experience opens those kinds of ideas up in an audience member’s mind, that for me would be a very important, possibly transformative takeaway—because we’re reminded, ultimately, of the intrinsic value of the arts and not just the instrumental value of the arts. Now: is that any different from the experience I want people to have when they go to the all-Brahms program with the Chicago Symphony? Probably not.

LS: It does seem that when you’re packaging this as “renegade,” you’re focusing on the process of creating this art, rather than just, “Let’s go hear these great works that are part of the canon.” I mean, how did they get to be part of the canon in the first place?

MK: Exactly.

LS: And what does that mean for us, and how and where we need to move our culture forward?

MK: That’s right. I think you’re right. I also think that accessing a lot of work really ultimately has everything to do with giving yourself permission. Einstein on the Beach, for example, is a five-plus hour work without an intermission …

* * *

In my next post: More from Michael Kondziolka on Einstein on the Beach.

What do you think? Do renegade works fill audiences with renegade spirit? Have you attended a ‘renegade’ work?

11/12 International Theater Series

This year’s International Theater Series features three productions at the Power Center. The series begins with Ireland’s acclaimed Gate Theater Company performing a double-bill of two one-act plays by Samuel Beckett, Endgame and Watt. As previously announced, the series continues with Einstein on the Beach, the seminal opera by Philip Glass and Robert Wilson with choreography by Lucinda Childs. Considered one of the most remarkable performance works of our time, this performances launches a world tour of what will likely be the last reconstructions of this work designed and led by its original creators. Closing the series is The Andersen Project, a solo performance created by Canadian theater visionary Robert Lepage and performed by Yves Jacques that explores sexual identity, unfulfilled fantasies, and the thirst for recognition and fame through Hans Christian Andersen’s timeless fables.

Subscription packages go on sale to the general public on Monday, May 9, and will be available through Friday, September 17. Current subscribers will receive renewal packets in early May and may renew their series upon receipt of the packet. Tickets to individual events will go on sale to the general public on Monday, August 22 (via www.ums.org) and Wednesday, August 24 (in person and by phone). Not sure if you’re on our mailing list? Click here to update your mailing address to be sure you’ll receive a brochure.

Samuel Beckett’s Endgame and Watt

Gate Theatre of Dublin

Michael Cogan, director

Thursday, October 27, 7:30 pm

Friday, October 28, 8 pm

Saturday, October 29, 8 pm

Power Center

Straight from Ireland comes the Gate Theatre, largely considered the interpreter of Beckett in the world. Endgame, like Waiting for Godot, is considered one of Beckett’s most important works, written in a style associated with the Theatre of the Absurd. The bizarre adventures of Watt (a novel written while Beckett was in hiding during World War II) and his struggles to make sense of the world around him is told with elegant simplicity, immense pathos, and explosive humor. This week-long residency will be accompanied by a week-long festival of the complete Beckett works on film.

Philip Glass & Robert Wilson’s Einstein on the Beach

Lucinda Childs, choreographer

Friday, January 20, 7pm

Saturday, January 21, 7pm

Sunday, January 22, 2pm

Power Center

“The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious.” — Albert Einstein

Widely credited as one of the greatest artistic achievements of the 20th century, this rarely-performed work will be reconstructed for a major international tour (including the first North American presentations ever held outside of New York City) nearly four decades after it was first performed and 20 years since its last production. Non-narrative in form, the work uses a series of powerful recurrent images as its main storytelling device, shown in juxtaposition with abstract dance sequences created by American choreographer Lucinda Childs. Prior to the production’s final technical rehearsals and world premiere in Montpelier, France, UMS will host the creators, musicians, performers, and crew for Einstein for three weeks as they reconstruct and rehearse the work for what is likely to be the final world tour designed and led by its creators. These early preview performances will be the only opportunity to see Einstein on the Beach in the Midwest.

Click the video below to watch some excerpts from Einstein on the Beach with audio commentary from collaborator Robert Wilson.

The Andersen Project

Ex Machina

Robert Lepage, artistic director

Thursday, March 15, 7:30 pm

Friday, March 16, 8 pm

Saturday, March 17, 8 pm

Power Center

Filled to the brim with his trademark humor and visual and technological brilliance, this off-the-wall masterpiece by Canadian theater visionary Robert Lepage stars Yves Jacques (Far Side of the Moon) in a one-man tour-de-force about a Canadian writer from the rock-and-roll milieu who is unexpectedly commissioned by the Opera Garnier in Paris to write a libretto for a children’s opera. Freely inspired by the timeless fables written by Hans Christian Andersen, who as it turns out, didn’t really like children, as well as anecdotes from the author’s personal diaries, The Andersen Project keenly explores unraveling relationships, personal demons, the thirst for recognition, and compromise that comes too late.

Return to the complete chronological list.

Renegade Series

Renegade

The focus on “renegades” in the 11/12 season examines thought-leaders and game-changers in the performing arts and encompasses performances that are part of the UMS International Theater Series, Choral Union Series, Divine Voices, Dance Series, and the Chamber Arts Series. Performances under this umbrella will take place in a ten-week period from January – March 2012 and include:

- Philip Glass & Robert Wilson’s Einstein on the Beach

- From the Canyons to the Stars, performed by the Hamburg State Symphony

- The Tallis Scholars, performing Tenebrae Responses by renegade Italian Renaissance composer Carlos Gesualdo

- Random Dance, a company started by Wayne McGregor , the resident choreographer at The Royal Ballet, Covent Garden, whose groundbreaking collaborations across dance, film, music, visual art, and science is evident in the company’s presentation of FAR

- Robert Lepage’s The Andersen Project, a solo performance created by this Canadian theater visionary that explores sexual identity, unfulfilled fantasies, and the thirst for recognition and fame through Hans Christian Andersen’s timeless fables

- The four concerts of the San Francisco Symphony’s American Mavericks festival. In addition to the three orchestral concerts noted in the Choral Union Series, members of the San Francisco Symphony will present a chamber music concert to close both the American Mavericks festival and the UMS focus on Renegades.

Subscription packages go on sale to the general public on Monday, May 9, and will be available through Friday, September 17. Current subscribers will receive renewal packets in early May and may renew their series upon receipt of the packet. Tickets to individual events will go on sale to the general public on Monday, August 22 (via www.ums.org) and Wednesday, August 24 (in person and by phone). Not sure if you’re on our mailing list? Click here to update your mailing address to be sure you’ll receive a brochure.

Return to the complete chronological list.

UMS Arts Roundup: November 19

Many members of the UMS staff keep a watchful eye on local and national media for news about artists on our season, pressing arts issues, and more. Each week, we pull together a list of interesting stories and share them with you. Welcome to UMS’s Arts Round-up, a weekly collection of arts news, including national issues, artist updates, local shout-outs, and a link or two just for fun. If you come across something interesting in your own reading, please feel free to share!

Arts Issues

- What’s next on the list to download to your ipod? Ballet!

- The use of captions during plays give theaters access to new audiences, including the hearing impaired.

- 2011 Edinburgh International Festival to focus on Asian culture and influence.

Artist Updates

- World famous composer Philip Glass writes a new opera, to premiere in 2013.

- Alongside 14 others, Yo-Yo Ma is awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom—the country’s highest civilian honor—from President Obama.

UMS News

- Annarbor.com performance review of Stew & the Negro Problem at the old Leopold’s pub. Additional performances on Friday and Saturday!

Local Shout-Outs

- Intriguing exhibit opens at DIA, looking at artist fakes and the detective work used to verify artworks.

- Students host EMU music festival featuring local bands.

Just For Fun

- Check out this circus-like version of “Swan Lake” that has lately been making the rounds on youtube. Amazing or horrifying? You decide!

The Four Seasons Like You’ve Never Heard Them Before…

With next Wednesday’s “Seasons Project” featuring the Venice Baroque Orchestra and violinist Robert McDuffie performing both Vivaldi’s Four Seasons and Philip Glass’s “American” Four Seasons in Hill Auditorium, we thought you might enjoy the video trailer for the concert…

…And the opportunity to identify the seasons from Philip Glass’s concerto. Robert McDuffie says, “I specifically asked Philip Glass for four large movements, originally thinking that we would be naming the movements as seasons — until we both disagreed on what was summer and what was winter. He said, this is a great opportunity actually… why don’t we just leave it up to the audience to decide?”

UMS Arts Roundup: October 22

Many members of the UMS staff keep a watchful eye on local and national media for news about artists on our season, pressing arts issues, and more. Each week, we pull together a list of interesting stories and share them with you. Welcome to UMS’s Arts Round-up, a weekly collection of arts news, including national issues, artist updates, local shout-outs, and a link or two just for fun. If you come across something interesting in your own reading, please feel free to share!

Arts Issues

- 25-year-old Yulianna Avdeeva of Russia won the 2010 International Frederic Chopin Piano Competition, the first woman to win in 45 years…but the award did not come without controversy.

Artist Updates

- Sankai Juku just wrapped up their 2-week-run at the Joyce Theater in New York–see the Huffington Post review here.

- People are Watching: Our staff’s favorite video this week is this stunning clip of Hibiki by Sankai Juku.

- Need to get your jazz fix? Check out two clips from the Hot Club of Detroit’s new release here and here.

- Meet Vijay Iyer: last week’s feature on NPR’s Fresh Air.

- Dig into the music: New York Times Magazine interviews Arvo Pärt, whose music appears on the Tallis Scholars’ upcoming concert.

UMS News

- AnnArbor.com preview of Sankai Juku‘s Power Center performances this weekend.

- AnnArbor.com preview of the Venice Baroque Orchestra and Robert McDuffie, featuring Vivaldi’s “Four Seasons” and Glass’s “American Four Seasons” concerti next Wednesday’s performance.

- AnnArbor.com review of the Jerusalem Quartet concert.

Local Shout-Outs

- Follow tenor Nicholas Phan, U-M School of Music alum, Ann Arbor native, and a soloist in this season’s Messiah, on his way to his Carnegie Hall debut.

Just For Fun

- Where will he be in 20 years, let alone 10? Watch 3-year-old Jonathan conduct Beethoven in his living room!

- Something’s Rotten in the State of Facebook…an NPR spoof on Hamlet.

UMS Arts Roundup: October 15

Many members of the UMS staff keep a watchful eye on local and national media for news about artists on our season, pressing arts issues, and more. Each week, we pull together a list of interesting stories and share them with you. Welcome to UMS’s Arts Round-up, a weekly collection of arts news, including national issues, artist updates, local shout-outs, and a link or two just for fun. If you come across something interesting in your own reading, please feel free to share!

Arts Issues

- The Detroit Symphony Orchestra strike continues, and the DSO has canceled orchestral concerts through November 7. Non-orchestral concerts, education programs, and rentals continue as scheduled.

Artist Updates

- Soprano Joan Sutherland died Sunday at age 83. Leave your memories of her three UMS performances here.

- Rudresh Mahanthappa launched his new website this week, where you can stream his latest album, Apex.

- Muti update: Riccardo Muti is out of the hospital, recovering from extreme exhaustion from prolonged stress.

- Name the seasons! Stream Philip Glass’ American Four Seasons and follow the Venice Baroque Orchestra/Robert McDuffie Seasons Project Tour on GoogleMaps.

UMS News

- The Mariinsky Orchestra, Valery Gergiev and Denis Matsuev opened our Choral Union Series on Sunday afternoon. You can also read comments from the audience.

- Review of last night’s Schubert concert by the Takács Quartet.

Local Shout-Outs

- If you’ve never been to the U-M Halloween Concert, it’s a real treat (with some tricks too)! Members of the University Symphony and Philharmonic Orchestras perform in this annual event on October 31 at Hill Auditorium.

Just For Fun

- Ok, maybe not “for fun”…but bedbugs were found last week in dressing rooms at Lincoln Center! They’ve turned up so far at the David H. Koch Theater, home of the New York City Ballet, and have spread to the Met.

- The YouTube Symphony Orchestra returns for its second year! Get out your instruments: audition submissions close on November 28.

UMS’s Arts Round-Up: July 23, 2010

Many members of the UMS staff keep a watchful eye on local and national media for news about artists on our season, pressing arts issues, and more. We thought we’d pull together a list of interesting stories each week and share them with you. Welcome to UMS’s Arts Round-Up, a weekly collection of arts news, including national issues, artist updates, local shout-outs, and a link or two just for fun. If you come across something interesting in your own reading, please feel free to share!

Many members of the UMS staff keep a watchful eye on local and national media for news about artists on our season, pressing arts issues, and more. We thought we’d pull together a list of interesting stories each week and share them with you. Welcome to UMS’s Arts Round-Up, a weekly collection of arts news, including national issues, artist updates, local shout-outs, and a link or two just for fun. If you come across something interesting in your own reading, please feel free to share!

National Issues

- You’ve come a long way, baby. NPR asked hundreds of women working in the music business what it’s like to be working as a female musician today. Hear from Deborah Voigt, Janis Ian, Sarah McLaughlin, Jennifer Higdon, and more.

- The New York Times asks why it’s called incidental music if it’s not so incidental.

Artist Updates

- The Washington Post offers a delightful profile of Paul Taylor on the eve of his 80th birthday.

- Philip Glass’s The American Four Seasons received its US premiere at the Aspen Music Festival. Check out the trailer for a sneak peak!

- Wondering what’s coming to Ann Arbor next year as part of NT Live’s high-definition broadcast theater series? Check out this review of the new hit musical, FELA!

Local Shout-Outs

- Looking for some outdoor fun after the Art Fairs? Check out the new Land of Nod music and camping festival in Jackson, featuring plenty of local acts including The Ragbirds, Macpodz, and The Satin Peaches.

Just For Fun

- Curious about just what goes into those elaborate costumes at the Met? The New York Times has the inside scoop.