Who Are We?

Théâtre de la Ville performs Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author at the Power Center in Ann Arbor on Oct 24-25, 2014. Photo by JL Fernandez.

While I was working on a biography of poet, playwright, and theatre director Federico García Lorca many years ago, I was startled to discover that Lorca had planned to meet up with the dramatist Luigi Pirandello in Italy in 1935. The two intended to collaborate—but Lorca cancelled the trip after Mussolini invaded Abyssinia (it was one of the rare overtly political gestures of Lorca’s life), and the two men never met.

I’ve often wondered what would have happened if they had. For both playwrights shared, among other things, a fascination with the nature of theater. Lorca probed the topic throughout his life, in plays that contain plays and rehearsals within plays, plays whose cast lists include directors and actors and playwrights (including Lorca himself). He introduced all manner of theatrical claptrap into these works—puppets, masks, screens (behind which identities abruptly change), miniature stages, outlandish costumes and props.

Pirandello was similarly obsessed. You see it big time in Six Characters in Search of an Author, a play that, if done well, should produce something like imaginative whiplash in the audience. (I’ve only seen the work produced once, in a student production at NYU, with way too much scenery-chewing. But having seen Théâtre de la Ville’s exquisitely nuanced production of Ionesco’s Rhinoceros two years ago in Ann Arbor, my hopes are high.)

What’s real? Who’s acting?

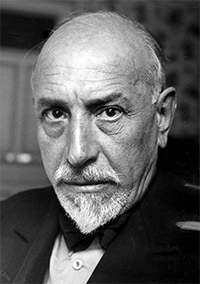

On left, Luigi Pirandello, and on right, Federico García Lorca.

What’s real? Who’s acting? Are the events and emotions we see onstage reality? Is what we experience and witness in “real life” acting? Can you trust what you see on a stage? In a conversation with your spouse or best friend or boss?

Aren’t these the questions that lie beneath the pleasures we associate with theater? (With film too, but I don’t think the experience is ever quite as acute on a screen.)

The setup for Pirandello’s exploration of theatrical artifice is straightforward: six purportedly fictional characters barge into a mostly empty theater to impose their story on a director and group of actors who are trying to rehearse a play. Actors become audience. Characters become actors. The layers multiply and confusions mount.

In line after line, we’re asked to consider the contradictions at the heart of play-making.

DIRECTOR: Then the theater is full of madmen, is that what you’re saying?

FATHER: Making what isn’t true seem true … for fun … Isn’t that your purpose, bringing imaginary characters to life?

Elsewhere the Father—one of Pirandello’s “six characters”—cries out that his story isn’t literature, it’s “life! Passion!” To which the Director responds: “That may be, but it won’t play.”

“What’s a stage?” a character asks toward the end of the play, and answers her own question. “It’s a place where people pretend to be very serious.”

The Empty Space

Exchanges like this abound—and make you question the theatrical enterprise and its conventions. Do we really need all the devices we’ve come to associate with the theater? The curtain and spotlights and scripts and applause? Peter Brook famously said (in his indispensable 1968 book The Empty Space) that in order for an act of theater to take place, all you need is for one person to walk across an empty space while another watches.

Brook published his book some 40 years after Pirandello wrote Six Characters, which opens on a stage whose atmosphere, Pirandello instructs, “is that of an empty theater in which no play is being performed.”

The Italian Pirandello grew up steeped in the venerable stuff of theater—the comic and tragic masks of the ancient Greek and Roman stage, the stock characters of thecommedia dell’arte. He understood (as did Lorca and that greatest of playwrights, Shakespeare) that identity is at the core of acting. As one of Pirandello’s six “characters” points out, “We all try to appear at our best, but we all know the unconfessable things that lie within the secrecy of our own hearts. We are not what we seem—even to ourselves.”

Don’t you change your personality according to the situation and your audience?

In another book I find indispensable, The Actor’s Freedom: Toward a Theory of Drama (1975), critic Michael Goldman probes precisely these questions. Identification is the “covert theme of drama,” Goldman writes. This isn’t simply a matter of actors identifying with roles but of “the making or doing of identity.” You watch an actor, onstage or on screen, and wonder where her private life stops and the public, performed one begins, what parts of herself we see revealed in her role.

“It should not be surprising, then,” says Goldman, “that the process of identification in this sense—of establishing a self that in some way transcends the normal confusions of self—is remarkably current as a theme in plays of all types from all periods, from Oedipus to Earnest to Cloud Nine.” Add Six Characters to that list.

And what about us? Are we characters—locked into our one and only story? Or actors, whose “solid reality as of this moment is destined to become the half-remembered dream of tomorrow,” as Pirandello’s Father puts it?

Questions to ponder, indeed. Endlessly.

Leslie Stainton’s most recent book is Staging Ground: An American Theater and Its Ghosts, a poignant and personal history of one of America’s oldest theaters, the Fulton Theatre in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

U-M Theater Community on Peter Brook’s The Suit

Director Peter Brook changed contemporary theater. His production of The Suit will be in Ann Arbor on February 19-22, 2014. We chat with University of Michigan faculty, as well as with former Royal Shakespeare Company director Michael Boyd, about why they’re excited to see the production and the importance of Brook’s work:

Interested in learning more? Check out our infographic of the highlights of Brook’s life and work.

Putting On “The Suit”

Editor’s note: Student volunteers at UMS often get the chance to take a deep dive into a performance or art form. In this essay, UMS Marketing intern Clare Brennan reflects on her experiences with “The Suit” directed by the legendary stage and film director Peter Brook. The performance will be at Ann Arbor’s Power Center on February 19-22, 2014.

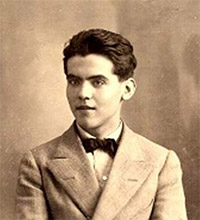

Photo: Clare Brennan and the UMS Student Committee take the suit around town as part of U-M Museum of Art’s “Love Art More” project. Photo by UMS Student Committee.

It’s not hard for me to remember one of the first books that really moved me. I was sitting in my living room, home alone on a bright August afternoon, finishing up some reading I’d been assigned for my last year of English in high school. I read the final paragraph, closed the back cover, and sat quietly for a while. I might’ve teared up a bit, if I’m being honest. The book was Alan Paton’s Cry, The Beloved Country, and it was then that I became infatuated with the stories and storytellers from South Africa.

As it turns out, my love for the French language and culture was growing right alongside this, as well as an absolute obsession with all things regarding Anglo-Saxon theater. Imagine, then, my elation when an opportunity to dive head first into The Suit fell into my lap. My nerdy heart fluttered. I accepted as nonchalantly as I could.

Apparently, my fixation with The Suit is not uncommon. Legendary theatrical director Peter Brook loved this story so much that, after directing the story once in French in 1999, he chose to return to it, this time in English. I had the chance to sit down with Michael Kondziolka, the Director of Programming here at UMS. He saw the debut of this production of The Suit last year in New York, and knew that Ann Arbor had to have the chance to see it. “It’s so painterly. A supreme colorist can use shadow and light and color and understands exactly how to use these different media to create a masterpiece. That’s what Peter Brook is doing. He knows how to use actors and written text and music and light and staging and movement and the audience, and how to craft all of that into something that is really powerful, really masterful.”

Of course, any discussion of South Africa must mention the recent passing of Nelson Mandela. The Suit is set on the cusp of Mandela’s most prominent years, and this energy of anticipation of what’s to come silently fills the stage. It provides an opportunity to see a South Africa without Mandela and his work, and as the world reflects on his incredible dedication to his country, taking a moment to step back and hear from those who came before him feels even more powerful.

With that context, The Suit might seem like a eulogy. Far from it. In talking with Michael, I got the chance to hear about what makes a Peter Brook piece tick. At the heart of each of his works is a dedication to simplicity. “This piece has a real lightness to it. And the lightness comes from the performance.” Over almost half- century of work, Brook has pared down his stages, from the intricate scenery of his staging of the Bard for the Royal Shakespeare Company to the openness of The Suit’s space. “It creates a sense of the fun of the performance. So you’ve got this really interesting visual experience. Your imagination is unlocked as an audience member, and that’s really entertaining and satisfying.” Brook trusts his audience, an honor not frequently given, and we’re free to reap the benefits.

While we covered many topics, my chat with Michael really focused on the music embedded in the show. From Schubert on the accordion to a poignantly placed introduction of Bach’s St. Matthew’s Passion (what Michael reverently referred to as “The Sistine Chapel of classical music”), it is evident that Brook knows exactly how to carefully weave music into his work. “Peter Brook is not only a master theater maker but he clearly is a student of culture, and the way in which he understands the meaning of these specific pieces of music and uses them to get his theatrical idea across.”

Studying up for The Suit has been a joy. Peter Brook knows how to tell a story, and his ability to transcend the barriers of the stage and approach each member of the audience with this incredible story of love and loss has no comparison. I’m so looking forward to seeing this show and finding what discoveries I still have left to make. The stage has a magical quality, and, in The Suit, it’s clear that Peter Brook knows it. “It’s pure poetry,” as Michael eloquently sums up. From what I can tell, I think he’s on to something .

Interested in learning more? Check out a brief infographic history of Peter Brook’s career or watch a storybook introduction to the performance.

Sources:

http://www.bouffesdunord.com/en/about-us/peter-brook

http://frenchculture.org/visual-and-performing-arts/events/us-premiere-suit-directed-peter-brook

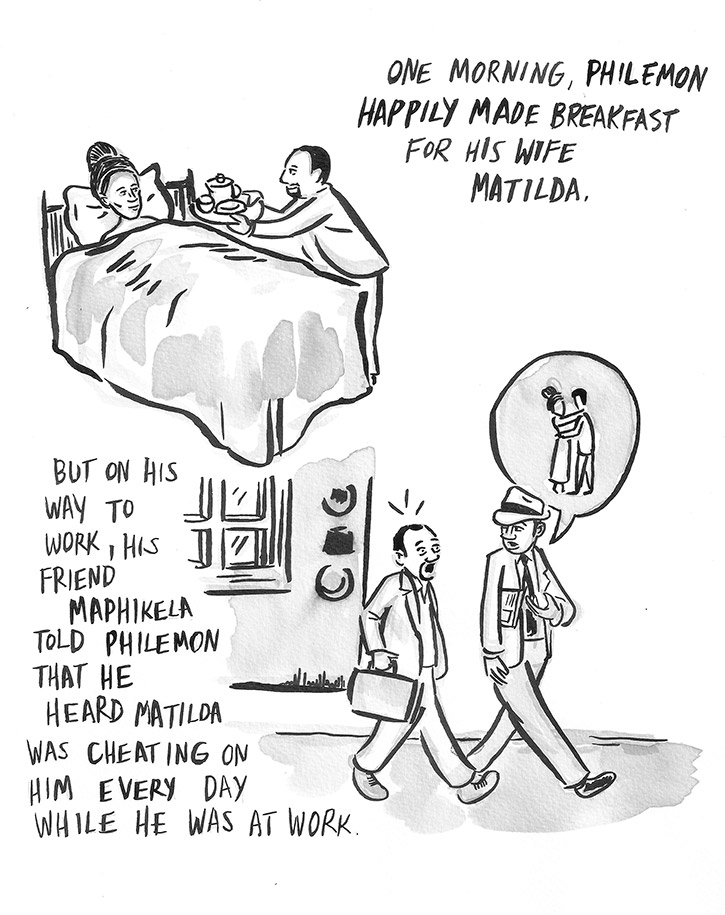

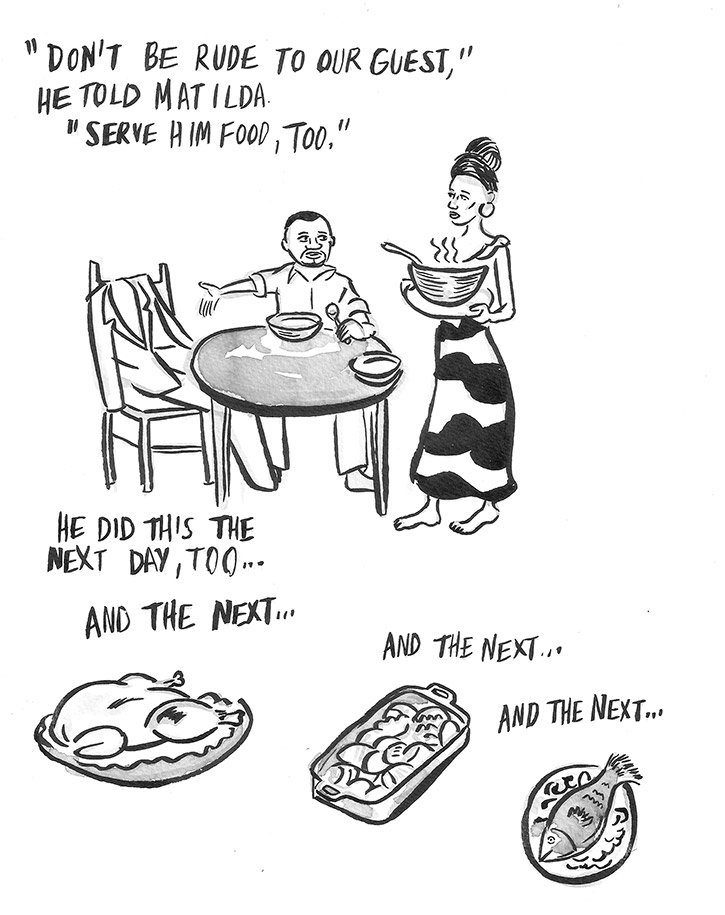

The Suit: A Storybook Introduction

The Suit will be at Ann Arbor’s Power Center on February 19-22, 2014. The play, directed by the renowned Peter Brook, is adapted from South African writer Can Themba’s witty, unsettling short story of the same name.

Our video is based on Brooklyn-based illustrator Nathan Gelgud’s “storybook” introduction to “The Suit.” Explore the stills from this video.

A [brief] UMS History Presentation: Peter Brook

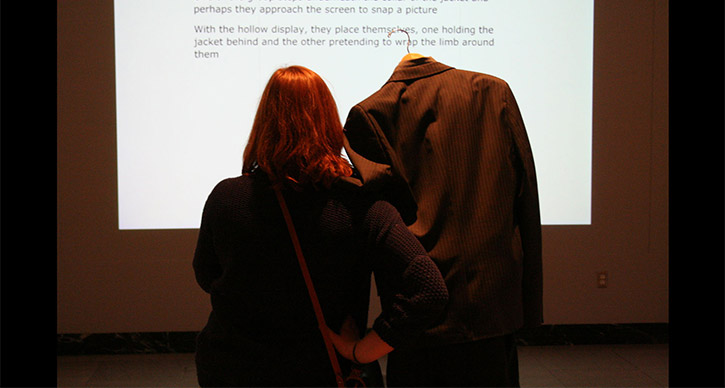

Photo: Peter Brook. Photo by Colm Hogan.

Director Peter Brook’s contributions to theater have spanned stage, film, and literary worlds. He directs The suit, performed by Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord at the Power Center in Ann Arbor February 19-22, 2014.

His legendary career has spanned decades and the world. Explore the timeline in this infographic:

The Suit: A Storybook Introduction

The Suit will be at Ann Arbor’s Power Center on February 19-22, 2014. The play, directed by the renowned Peter Brook, is adapted from South African writer Can Themba’s witty, unsettling short story of the same name.

Can Themba was a short story writer and journalist, writing investigative pieces for Drum Magazine in addition to fiction in the 1950s and sixties. Peter Brook’s 71-year career spanned the Royal Shakespeare Company, London’s West End, Paris’s Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord, and countless other companies and has irrevocably changed contemporary theater.

Brooklyn-based illustrator Nathan Gelgud has created a “storybook” introduction to The Suit.

See how things shape up on stage starting February 19. Tickets are on sale now.

These illustrations originally appeared on BAM blog. More: nathangelgud.com

Interested in reading the story? Get a special deal on the book and the performance through our UMS Book Club with Nicola’s Books.

The Power (or Not) of Place

Editor’s note: The National Theatre of Scotland performs A Christmas Carol on December 17 – January 3, 2016. The performance take place in an unconventional space: inside a box on the stage of the theater.

In my early twenties, I joined a children’s theater company and for half a year toured southeastern Pennsylvania putting on plays in elementary schools. I’d done my share of theater elsewhere, but nothing approached the energy of those performances. Every day we’d troupe off to another school to give our show and do a workshop. I’d been told children were the most demanding of audiences, but I never felt less than welcome anywhere we went, maybe because most kids were giddy with pleasure at the arrival of a bunch of costumed adults in their midst. (I played a dog.) It’s one thing to go to the theater, another to have it erupt in your cafeteria on a rainy weekday morning, much the way medieval pageants used to erupt in town squares.

We had little scenery and one change of clothes. I suspect we weren’t far from the kind of enterprise Peter Brook had in mind when he said the only thing needed for an act of theater to take place is for one person to walk across an empty space while someone else watches. The kids who sat cross-legged on carpet squares watching us perform certainly didn’t seem to distinguish between what we were doing and what took place downtown in the fancy 19th-century opera house our troupe called home—the kind of building Brook had in mind when he said of the theater: “Red curtains, spotlights, blank verse, laughter, darkness, these are all confusedly superimposed in a messy image covered by one all-purpose word.”

Photo (L to R): Palladio’s Olimpico, Radio City Music Hall, the Corner Brewery.

God knows the human thirst for stories has led to some amazing spaces: the ancient Greek amphitheaters with their literal sky, Palladio’s ornate Olimpico with its figurative one, Shakespeare’s Globe, the Sydney Opera House, Radio City Music Hall. But as pieces like Prudencia Hart remind us, it doesn’t much matter where plays are performed—or maybe it does matter, just not in ways we’ve been taught to expect. “Space that has been seized upon by the imagination,” writes Gaston Bachelard, “cannot remain indifferent space subject to the measures and estimates of the surveyor.” Performance transforms the sites we inhabit. I’ve often wondered if those elementary-school kids thought differently about their surroundings after we’d left. I hope so. Surely Ypsi’s Corner Brewery will be changed, perhaps in lasting ways, by what takes place inside it this January 8-13.

In a 2010 TED talk, Ben Cameron of the Doris Duke Foundation suggested that many purpose-built arts venues “were designed to ossify the ideal relationship between the artist and audience most appropriate to the 19th century.” Cameron and others argue that unless performing arts organizations rupture traditional thinking about arts settings, the whole culture of performance will stagnate.

It strikes me that what’s happening in the performing arts—where conventional performance venues are increasingly yielding to breweries, planetariums, armories, rivers (our own Huron!), and the local multiplex (witness the global appeal of the Met’s live broadcasts)—is not unlike what’s happening in the world of print publishing. Where either will end up is anyone’s guess, but we’re clearly changing the way we communicate—and with whom. When the Boston Lyric Opera presented two free outdoor performances of Carmen in 2002, more than 100,000 people showed up. A third of them were seeing an opera for the first time.

The National Theatre of Scotland proudly states on its website that it has “no building,” and therefore has “no bricks-and-mortar institutionalism to counter, nor the security of a permanent home in which to develop. All our money and energy can be spent on creating the work”—which they perform in places as varied as car parks, forests, Edinburgh’s Royal Lyceum, and Ypsi’s Corner Brewery.

Back when I toured with the kids’ theater troupe, we had no box office, no lobby, no lights, no stagehands, no drops descending from on high, no tickets or sound system or props— just ourselves and what we could carry in the back of a station wagon. Our audiences didn’t care. Maybe some of it had to do with their age. But I’m sure it also had to do with the enduring power of make-believe, the freedom that actors represent, and the startling discoveries that can happen when a familiar space is made new, and the audience with it.