Watch & Listen: Eric Owens and Lawrence Brownlee Duo Recital

Performance and live webcast from March 16, 2019 in Hill Auditorium.

Eric Owens, bass-baritone

Lawrence Brownlee, tenor

Myra Huang, piano

Full Program

Mozart “Se vuol ballare” from Le Nozze di Figaro (Mr. Owens)

Mozart “Il mio tesoro” from Don Giovanni (Mr. Brownlee)

Verdi “Infelice! E tuo credevi” from Ernani (Mr. Owens)

Donizetti “Voglio dire, lo stupendo elisir” from L’elisir d’amore (Mr. Brownlee, Mr. Owens)

Donizetti “Una furtiva lagrima” from L’elisir d’amore (Mr. Brownlee)

Faust “Le veau d’or” from Faust (Mr. Owens)

Donizetti “Ah! mes amis, quel jour de fête!” from La fille du regiment (Mr. Brownlee)

Bizet “Au fond du temple saint” from Les Pêcheurs de Perles (Mr. Brownlee, Mr. Owens)

— Intermission —

(featuring interviews with great American tenor George Shirley and the evening’s soloists)

Traditional Spirituals

arr. Damien Sneed “All Night, All Day” (Mr. Brownlee)

arr. Hall Johnson “Deep River” (Mr. Owens)

arr. Damien Sneed “Come By Here” (Mr. Brownlee)

“Give Me Jesus” (Mr. Owens)

arr. Margaret Bonds/Craig Terry “He’s Got the Whole World In His Hands” (Mr. Brownlee, Mr. Owens)

American Popular Songs

Harold Vicars and Clarence Lucas, Arr. Terry “Song of Songs” (Mr. Brownlee, Mr. Owens)

Harry Warren and Al Dubin, Arr. Terry “Lulu’s Back In Town” (Mr. Brownlee)

Frank Loesser and Louis Alter, Arr. Terry “Dolores” (Mr. Brownlee, Mr. Owens)

Oscar Hammerstein II and Richard Rogers “Some Enchanted Evening” from South Pacific (Mr. Owens)

Vincent Youmans “Through the Years” (Mr. Brownlee, Mr. Owens)

Gospel Favorites

“I Don’t Feel No Ways Tired” (Mr. Brownlee)

“Every Time I Feel the Spirit” (Mr. Brownlee, Mr. Owens)

Video: The Gershwins’ Porgy & Bess

Considered one of the greatest operas of its time, The University of Michigan’s School of Music, Theatre, & Dance details the significance of performing The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess in concert.

UMS presents The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess: Opera in Concert in association with the School of Music, Theatre, & Dance on Saturday, February 17.

The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess and the Quest for American Opera

This essay is written in conjunction with The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess. UMS Presents Opera in Concert: The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess Saturday, February 17th at Hill Auditorium in Ann Arbor.

“The Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess and the Quest for American Opera” is written by Mark Clague, the Editor-in-Chief of the George and Ira Gershwin Critical Edition.

Photo: Porgy and Bess. Courtesy of Ira and Leonore Gershwin Trusts.

For me, the opera Porgy and Bess (1935) is about resilience, about a community’s hope for a better future despite the cruel evidence of experience. Catfish Row amplifies the struggle of American society with racial injustice, poverty, sexism, addiction, sexual violence, natural disaster, murder, and the divisions of society into north and south, sacred and secular, black and white. I wish that performing this very human drama—written and premiered more than 80 years ago—was simply an act of remembrance. I wish that it served only as a reminder of a past forgotten at our peril, of inequities and diseases vanquished, of civil rights heroes who, responding to injustice across the nation, bravely confronted and solved these very American problems. If this were true, Porgy and Bess would celebrate a transcendent human spirit while serving as a warning about an era that should never return. Unfortunately, Porgy and Bess is not simply a memory, but a living document. The injustices it confronts remain.

It is thus with tragic intensity that in 2018 Porgy and Bess still expresses a potent and contemporary urgency that resonates with our everyday lives. The opera’s plot is propelled by the bias of white law enforcement—false accusations, facile assumptions, a rush to judgment in the absence of real justice—while today black men in America are disproportionally killed by the police. In Act II, a hurricane kills most of the men of the fishing village, while stealing both mother and father from an infant in whom hopes of a bright future had been placed. This past year in the U.S., three major hurricanes—Harvey, Irma, and Maria—hit American shores, making the storm’s warning bells in the opera that much more potent. When Crown attacks Bess during the Kittiwah Island picnic, it recalls the growing list of accusations of sexual misconduct in today’s news. At the end of the opera, addiction enslaves Bess to a life of prostitution, while in 2016 opioid addiction killed more than 20,000 Americans. In facing these issues, performing Porgy and Bess offers an opportunity for dialogue—not just about the past but about the present.

The insidious danger of Porgy and Bess as a cultural monument is that its black characters can be interpreted as caricatures, not dramatic personae. In a society in which whites are privileged and blacks are not, the enthralled listener to Gershwin’s music can experience Catfish row uncritically. Crown can be seen not as a troubled contradiction caught in a desperate cycle of survival and addiction, but as a stereotype reinforcing white fears of black violence. Read in racist terms, the poverty of Catfish Row becomes emblematic of black (in)capability rather than a depiction of a community of working class strivers facing a mountain of unequal opportunity.

To sponsor a performance of Porgy and Bess, then, is to take on the responsibility for contextualizing and informing the opera’s audience of both its racist dangers and its artful activism.

As a white man leading the Gershwin Initiative at the University of Michigan, I have struggled with the meaning of preparing the score of Porgy and Bess for posterity. What is the opera’s legacy? I admit that in 2013, when we began work on the new score only months after the re-election of the United States’ first black President, the question seemed all but answered. Today the question is again potent. On one hand, I, too, am enchanted by George Gershwin’s music, Ira’s words, and the Heyward’s story, which combine to forge what for me is the opera’s very human expression of passion, pain, and possibility. I was further driven by personal loyalty to my fellow scholar, Wayne Shirley, as I want to help bring his virtuoso feat of scholarly editing to print.

Yet, ultimately, the answer to this question cannot be mine. I am sensitive to the call from former U-M professor Harold Cruse (1916–2005) asking black artists of the 1960s to boycott Porgy and Bess. As described in his 1967 book The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual, Gershwin’s opera was “a symbol of that deeply engrained, American cultural paternalism” that obscured black artists’ originality in “Negro theatre, music, acting, writing, and even dancing, all in one artistic package.” For Cruse, the success of Porgy and Bess became a barrier to the realization of other new works of black authorship.

Photo: Porgy and Bess. Courtesy of Ira and Leonore Gershwin Trusts.

The way out of this paradox of appropriation is to democratize the controls of cultural production such that African American writers, lyricists, and composers can tell their own stories. And it cannot stop there. #OscarsSoWhite must give way to more than Selma, Moonlight and Get Out. The theater must go beyond Hamilton. Works by women, Latin Americans, Native Americans, Asian American—any and all authors—deserve a chance to thrive on their artistic merits and message.

Studying Porgy and Bess has convinced me that its all-white creative team, while writing from their own necessarily limited perspective and experiences, saw the opera as an opportunity to bring the talents of black artists to the cultural mainstream. Their activism—if it can be called that—balanced entertainment with a focus on an American experience typically excluded from popular production. While African American composers such as Scott Joplin, Harry Lawrence Freeman, and James P. Johnson had written operas about the black experience before Porgy and Bess came on the scene, the celebrity of George Gershwin was necessary in 1935 to bring the story of black America to Broadway. That the composer turned down a $5,000 commission from New York’s Metropolitan Opera (about $100,000 in today’s dollars), in order to avoid the use of white choristers in blackface, speaks to the composer’s own growth since the failure of his 1921 blackface musical drama Blue Monday.

Countless musical moments in Porgy and Bess speak to the Gershwins and Heywards’ respect for black creativity. The composer spent nearly ten years preparing for the work, after reading DuBose Heyward’s novel Porgy in 1926. Gershwin’s creative gifts were so facile that such a period of study and preparation was unprecedented in his professional life. He seemed to know that Porgy and Bess would be the most challenging project he had yet faced.

The lullaby “Summertime” is the first aria heard in the opera. It gives voice to the dreams of a mother for her child. The beauty of its first note—a difficult entrance, soft and high in the soprano’s tessitura, belies the challenges facing Jake and Clara’s newborn son. The song’s hope and soaring lyricism serves as a tragic foil that foreshadows the loss to come, yet its endless melody is also the seed of the resilience that will allow Catfish Row to carry on after tragedy.

Gershwin did not quote African American music in Porgy and Bess verbatim, but created original music that evokes its style and sensibilities. His music draws from the performances of Cab Calloway in New York, and especially from the music of the Gullah people, who lived on and around the Georgia Sea Islands near Charleston, South Carolina, where the opera is set. Gershwin resided on one of these islands—Folly Island—for a month in the summer of 1935 to experience its soundscape. Echoes of his research can be heard throughout the opera, as when Robbins is killed and his wife Serena sings “My Man’s Gone Now,” an intimate cry of love lost and dreams thrown into disarray. In response, the Catfish Row community rallies to support his widow and their children, mirroring their devastation in the spiritual-like anthem “Gone, Gone, Gone.”

The paternalism of which Cruse complained is evident in the Heywards’ introduction to the play Porgy, upon which the opera’s libretto is based. However, it also reveals the playwrights’ excitement to invite black actors into a collaborative process in which they would contribute their own creativity to the storytelling. In fact, the vendors’ cries—selling deviled crab, honey, and strawberries—were not part of the original novel, but instead were added to the text by the black actors themselves to increase the drama’s realism. In the opera, singers can steal the show with these evocative calls. The Strawberry Woman and Crab Man’s rising slides give voice to the day-to-day struggle for existence with virtuoso power and emotional eloquence. The collaborative legacy hidden in these moments between art and artist continues to nourish the opera as a whole today, as a new generation of singers bring their own talents, character research, and emotional understandings to some of most demanding and artistically challenging vocal roles in all of opera’s repertory.

Photo: George and Ira Gershwin and Dubose Heyward. Courtesy of Ira and Leonore Gershwin Trusts.

Finally, Porgy’s climactic expression of duty in the face of the impossible—“Lord, I’m On My Way”—fulfills for me the essential message of DuBose Heyward’s novel and the newspaper clipping that served as its inspiration. Heyward had read a brief notice in a Charleston paper about Samuel Smalls, a local character and disabled beggar known as “Goat Sammy.” Smalls was apparently wanted by the police on the charge of attempted murder, and, for Heyward, the thought that a black man, crippled both physically and economically, could be so bold as to attempt to take another’s life seemed the inspiration for a powerful story. Born and raised in Charleston, the writer changed “Sammy” to “Porgy,” resulting in the 1925 novel. It is a tale of the transformation of a weak beggar into a determined, strong, and dynamic force.

Prior to studying Heyward’s novel, the ending of Gershwin’s opera always left me disappointed. Gershwin’s optimistic music seemed to say it was possible that Porgy could find Bess, but I heard Porgy’s determination as delusion. Now, it seems to me that the opera is really the tale of Porgy’s transformation. He begins the opera as a smart, but impotent survivor who scrapes subsistence from coins dropped by sympathetic passersby. By the end of the opera, he has defeated Crown—the opera’s symbol of ultimate strength and manhood—inheriting his mantle. Thus, I have come to see Porgy’s determination to rescue Bess not as fantasy but as his newfound duty, whatever the odds. Catfish Row, too, moves on. The community itself may, in fact, be the true hero of the opera. Its heroism lies in its resilience, the inevitability of its resolve to continue in the face of repeated tragedy.

I find this same resilience in the opera itself. Porgy and Bess is a survivor. While Gershwin’s early death two years after the opera’s premiere made Porgy and Bess the heartbreaking finale of an American creative legacy, the composer certainly never intended this work to mark an endpoint. His folk opera was just another waystation on a creative journey, an improbable quest to create a credible American contribution to a European art form, using Broadway song and African American spirituals as musical inspiration. Gershwin hoped to forge a distinctively American music that gave voice to his age, with all its promise and problems. That quest does not end with Porgy and Bess.

This essay is written in conjunction with The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess. UMS Presents Opera in Concert: The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess Saturday, February 17th at Hill Auditorium in Ann Arbor.

“The Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess and the Quest for American Opera” is written by Mark Clague, the Editor-in-Chief of the George and Ira Gershwin Critical Edition.

UMS’s Arts Roundup: October 1

Many members of the UMS staff keep a watchful eye on local and national media for news about artists on our season, pressing arts issues, and more. Each week, we pull together a list of interesting stories and share them with you. Welcome to UMS’s Arts Round-up, a weekly collection of arts news, including national issues, artist updates, local shout-outs, and a link or two just for fun. If you come across something interesting in your own reading, please feel free to share!

ARTS ISSUES

- The orchestral world continues to change as Zarin Mehta steps down as President of the NY Philharmonic.

- And so does the opera world — Placido Domingo is also reducing his commitments.

- But James Levine is finally back after months of health issues that curtailed his ability to conduct.

- Arts jobs count too–NEA chief advocates the legitimacy and worth of creative jobs in the arts during hard economic times.

- Is opera worth the expense? Alex Ross voices his opinion regarding the Met’s $16 million Wagner opera cycle.

ARTIST UPDATES

- Stephen Sondheim at 80: An interview with the man who revolutionized the world of musical theater.

- Dancer/choreographer Trisha Brown featured at the Whitney Museum of American Art in program of her seminal works.

UMS NEWS

- Rosanne Cash brings superb voice and new depth to classic and new country tunes alike during her performance of “The List” at Hill Auditorium on Saturday night [review].

- Jordi Savall brings music of Spain and Mexico to St. Francis Church [review].

LOCAL SHOUT-OUTS

- Play the piano? Always wanted to try? Now’s your chance! Pull up a seat and try out any of the seven Pianos ‘Round Town, located on the sidewalks of Depot Town and Downtown Ypsilanti.

- And you can play your own melody for UMS — at intermission of the Mariinsky Orchestra and Takacs Quartet concerts (Oct. 10 and Oct. 14 respectively).

- A potential sign of hope emerges for struggling arts institutions in Michigan with the Detroit Institute of Arts likely to get $10M from the state.

JUST FOR FUN

- Once again, the hills will be alive with the sound of music, as Oprah reunites the original Sound of Music cast members.

- Dancers morph into human sculptures around Manhattan as part of the Bodies in Urban Spaces project.

This Day in UMS History: Beverly Sills (September 23, 1977)

This Day in UMS History – September 23, 1977

Hill Auditorium

Beverly Sills, soprano

Charles Wadsworth, piano

Let the Bright Seraphim from Samson–Handel

Un moto di gioia, K. 579–Mozart

Bester Jüngling from Der Schauspieldirektor, K. 486–Mozart

Alleluia from Exsultate Jubilate, K. 165–Mozart

Many artists presented by UMS over its 132-year history have a long and rich history of performances with the organization. Soprano Beverly Sills was certainly no exception. Throughout the 1970s, Beverly Sills made numerous appearances under UMS auspices, culminating with this, her final appearance in 1977, just a few short years before announcing her retirement in 1980.

The late 60s and early to mid 70s were considered the high points of Beverly Sills’ career, as evidenced by her appearance on the cover of Time magazine in 1971, where she was described as “America’s Queen of Opera.” Beverly Sills’ first UMS appearance on January 30, 1971 was also a solo recital with Charles Wadsworth accompanying her on piano. On that particular program, Sills sang three arias from Handel’s opera seria Giulio Cesare. It is interesting to note that in 1966, Sills’ performance as Cleopatra in the New York City Opera’s revival of Handel’s then virtually unknown Giulio Cesare, is what many argue made her an international opera star.

Her final UMS program featured an aria from Handel’s oratorio Samson, considered by many to be one of Handel’s finest dramatic works, as well as three pieces by Mozart: concert aria “Un moto di gioia”, “Bester Jüngling” from the comic singspiel Der Schauspieldirektor (one of the only four vocal numbers in that piece), and “Alleluia” from the final allegro section of Mozart’s religious solo motet Exsultate Jubilate.

Following her retirement from performing, Beverly Sills remained quite active with the New York City Opera, serving on their board until 1991. Following that, she also served as chairman of Lincoln Center until 2002, and then as chairman of the Metropolitan Opera. Beverly Sills lost her battle with lung cancer on July 2, 2007 at the age of 78.

I hope you will take a moment to enjoy the video below and hear for yourself (if you weren’t able to attend any of her UMS performances!) the beauty and purity of tone of Beverly Sills’ voice as she sings one of my all-time favorite Mozart arias “Ruhe sanft, mein holdes Leben” from Zaide.

UMS’s Arts Roundup: September 3

Many members of the UMS staff keep a watchful eye on local and national media for news about artists on our season, pressing arts issues, and more. We thought we’d pull together a list of interesting stories each week and share them with you. Welcome to UMS’s Arts Round-up, a weekly collection of arts news, including national issues, artist updates, local shout-outs, and a link or two just for fun. If you come across something interesting in your own reading, please feel free to share!

Arts Issues

- “Soundcheck Smackdown” looks at the impact and value of live cinema broadcasts.

- The New York Times asks, “Does music make you exercise harder?”

Artist Updates

- Detroit Symphony Orchestra musicians authorize strike after talks fail

- A look at the Royal Shakespeare Company’s new digs

- The struggles of historic Beijng Opera in the 21st Century

- The Village Voice chats with jazz pianist Vijay Iyer about his new album, Solo

Local Shout-Outs

- No Labor Day Weekend plans? Head downtown to the 2010 Detroit International Jazz Festival.

Just For Fun

- Graduating from Kindergarten hardly an accomplishment for this 6-year-old piano prodigy.

- Need to kickstart your workday? Flashmob-turned-flashdance got things jumping at Liverpool Station.

UMS Arts Round-up: August 6

Many members of the UMS staff keep a watchful eye on local and national media for news about artists on our season, pressing arts issues, and more. We thought we’d pull together a list of interesting stories each week and share them with you. Welcome to UMS’s Arts Round-up, a weekly collection of arts news, including national issues, artist updates, local shout-outs, and a link or two just for fun. If you come across something interesting in your own reading, please feel free to share!

Many members of the UMS staff keep a watchful eye on local and national media for news about artists on our season, pressing arts issues, and more. We thought we’d pull together a list of interesting stories each week and share them with you. Welcome to UMS’s Arts Round-up, a weekly collection of arts news, including national issues, artist updates, local shout-outs, and a link or two just for fun. If you come across something interesting in your own reading, please feel free to share!

National Issues

- In Seattle, dance class (modeled after Mark Morris’ Dance for PD) helps Parkinson’s patients

Artist Updates

- Alec Wilkinson of The New Yorker sits in on Wynton Marsalis’s latest project

- Politics as unusual? Wyclef Jean contemplates run for Haitian presidency

- A match made in heaven or a shotgun wedding? The Wall Street Journal discusses a possible merger between the Kennedy Center and the National Opera

- Boston Pops conductor Keith Lockhart takes the helm at the BBC Concert Orchestra

Local Shout-Outs

- Ann Arbor theater troupe Performance Network announces its 2010/11 season.

- Blackbird Theatre, another Ann Arbor theater company, spreads its wings with a move to the Kerrytown District

Just for Fun

“Flash Opera” at the Reading Terminal by the Philadelphia Opera Chorus!

UMS’s Arts Round-Up: July 23, 2010

Many members of the UMS staff keep a watchful eye on local and national media for news about artists on our season, pressing arts issues, and more. We thought we’d pull together a list of interesting stories each week and share them with you. Welcome to UMS’s Arts Round-Up, a weekly collection of arts news, including national issues, artist updates, local shout-outs, and a link or two just for fun. If you come across something interesting in your own reading, please feel free to share!

Many members of the UMS staff keep a watchful eye on local and national media for news about artists on our season, pressing arts issues, and more. We thought we’d pull together a list of interesting stories each week and share them with you. Welcome to UMS’s Arts Round-Up, a weekly collection of arts news, including national issues, artist updates, local shout-outs, and a link or two just for fun. If you come across something interesting in your own reading, please feel free to share!

National Issues

- You’ve come a long way, baby. NPR asked hundreds of women working in the music business what it’s like to be working as a female musician today. Hear from Deborah Voigt, Janis Ian, Sarah McLaughlin, Jennifer Higdon, and more.

- The New York Times asks why it’s called incidental music if it’s not so incidental.

Artist Updates

- The Washington Post offers a delightful profile of Paul Taylor on the eve of his 80th birthday.

- Philip Glass’s The American Four Seasons received its US premiere at the Aspen Music Festival. Check out the trailer for a sneak peak!

- Wondering what’s coming to Ann Arbor next year as part of NT Live’s high-definition broadcast theater series? Check out this review of the new hit musical, FELA!

Local Shout-Outs

- Looking for some outdoor fun after the Art Fairs? Check out the new Land of Nod music and camping festival in Jackson, featuring plenty of local acts including The Ragbirds, Macpodz, and The Satin Peaches.

Just For Fun

- Curious about just what goes into those elaborate costumes at the Met? The New York Times has the inside scoop.

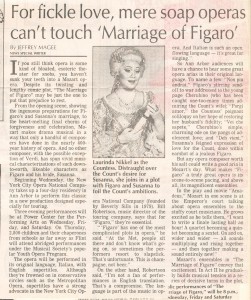

This Day in UMS History: New York City Opera , The Marriage of Figaro (Feb 13-15, 1991)

February 13-15, 1991

Power Center, Ann Arbor

New York City Opera

The Marriage of Figaro

Music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Libretto by Lorenzo da Ponte

While Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro may be timeless, opera production sure isn’t. The program notes for this production of Figaro note that the company “features its popular and much-praised supertitles, an innovation in opera that clarifies all of the action onstage while preserving the integrity of the original language libretto.” Opera plots are complicated enough as it is without having to worry about reading the translations by the dim light in the theatre! And yet only twenty years ago, that’s exactly what audiences had to do.

The New York City Opera was founded in 1943 and, in addition to opera gems such as Figaro, has a repertoire of 273 works spanning five centuries of music and including 29 world premieres and 61 American and/or New York premieres of such notable works as Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle, Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Shostakovich’s Katerina Ismailova, Prokofiev’s The Love for Three Oranges and The Flaming Angel, Schoenberg’s Moses und Aron, and Glass’ Akhnaten. The company has been a leading showcase for young artists, helping to launch the careers of more than 3,000 singers, including UM alumnus David Daniels, Plácido Domingo, Renée Fleming, and Beverly Sills.

“This day in UMS History” is an occasional series of vignettes drawn from UMS’s historical archive. If you have a personal story or particular memory from attending the performance featured here, we’d love to hear from you in the comments.