Last but not least: Pianist Sir András Schiff on Last Sonatas Project

Editor’s note: Pianist Sir András Schiff performs three concerts of the “The Last Sonatas” by Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert February 16-20, 2016. Below is his reflection on the project.

Photo: Sir András Schiff. Courtesy of the artist.

“Alle guten Dinge sind drei” — all good things are three, according to this German proverb that must have been well-known to Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert. Introducing their last three piano sonatas in three concerts — twelve works, twelve being a multiple of three — is a fascinating project that can demonstrate the connections, similarities and differences among these composers.

The sonata form

The sonata form is one of the greatest inventions in Western music, and it is inexhaustible. With our four masters of Viennese classicism it reached an unprecedented height that has never been equaled, let alone surpassed. Mozart and Beethoven were virtuoso pianists while Haydn and Schubert were not, although they both played splendidly (Schubert’s playing of his own Lieder had transported his listeners to higher spheres and brought tears to their eyes). The piano sonatas are central in their œuvres and through them we can study and observe the various stages of their development.

Lateness is relative, of course; Haydn (1733-1809) and Beethoven (1770-1827) lived long. Mozart (1756-1791) and Schubert (1797-1828) died tragically young. It’s the intensity of their lives that matters. In the final year of his life Schubert wrote the last three piano sonatas, the C Major string quintet, the song-cycle “Schwanengesang” and many other works. What more could we ask for? These last sonatas of our four composers are all works of maturity. Some of them – especially those of Haydn – are brilliant performance pieces; others (Beethoven, Schubert) are of a more intimate nature – it isalmost as if the listener were eavesdropping on a personal confession.

Lateness is relative

Both Beethoven and Schubert had worked on their final three sonatas simultaneously; they were meant to be triptychs. Similarly, Haydn’s three “London sonatas” — the only works in this series that weren’t written in Vienna — were inspired by the new sonorities and wider keyboard of the English fortepianos and belong definitely together. It would be in vain to look for a similar pattern in Mozart’s sonatas. For that let’s consider his last three symphonies — but his late music is astonishing for itsmasterful handling of counterpoint, its sense of form and proportion, its exquisite simplicity.

Let me end with a few personal thoughts. The last three Beethoven sonatas make a wonderful programme. They can beplayed together, preferably without a break. Some pianists like to perform the last three Schubert sonatas together. This, at least for me, is not a good idea. These works are enormous constructions, twice as long as those of Beethoven, and the emotional impact they create is overwhelming, almostunbearable. It is mainly for this reason that I am combining Beethoven and Schubert with Haydn and Mozart. They complement each other beautifully, in a perfect exchange of tension and release. Haydn’s originality and boldness never fail to astonish us. Who else would have dared to place an E Major movement into the middle of an E-flat Major sonata? His wonderful sense of humour and Mozart’s graceful elegance may lighten the tensions created by Beethoven’s transcendental metaphysics and Schubert’s spellbinding visions.

Great music is always greater than its performance, as Arthur Schnabel wisely said. It is never easy to listen to, but it’s well worth the effort.

Pianist Sir András Schiff performs three concerts of the “The Last Sonatas” by Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert February 16-20, 2016.

Are there artists whose “late” creativity you admire? Discuss in the comments below.

What is a Basset Horn?

Kari Dion is Programs Assistant at the Ann Arbor Summer Festival and clarinetist for the Akropolis Reed Quintet. Wind players of the Chicago Symphony come together for this special concert that features two of Mozart’s compositions for wind ensemble. See Chicago Symphony Winds perform Sunday, March, 22.

Glimmers of Light and Dark with the London Philharmonic

The London Philharmonic’s concert this Tuesday, December 6, in Hill Auditorium, features an intriguing program of the familiar, dramatic and mystifying. With Mozart’s beloved Violin Concerto no. 5, Matthias Pintscher’s seething and violent towards Osiris (2005) and Tchaikovsky’s rarely performed “Manfred” Symphony, the performance will begin in a delicate, comfortable musical environment and then take the audience on a wild ride through space and time, concluding with a prodigious and fantastical tone poem.

The London Philharmonic’s concert this Tuesday, December 6, in Hill Auditorium, features an intriguing program of the familiar, dramatic and mystifying. With Mozart’s beloved Violin Concerto no. 5, Matthias Pintscher’s seething and violent towards Osiris (2005) and Tchaikovsky’s rarely performed “Manfred” Symphony, the performance will begin in a delicate, comfortable musical environment and then take the audience on a wild ride through space and time, concluding with a prodigious and fantastical tone poem.

The Mozart concerto opening the evening’s music is an admittedly incongruous aperitif to the Pintscher and Tchaikovsky, simply because those later works are rooted in extra-musical narratives, as I will explain later. The Violin Concerto no. 5 is better known as one of Mozart’s greatest achievements in the concerto repertoire, seamlessly melding technical demands on the soloist with his typically beguiling melodic ideas. According to ClassicalArchives.com, this work may be the most commonly performed violin concerto in classical music. Though the piece employs a broadened dramatic scope – and even includes the direction “aperto”, something Mozart usually limited to his operatic scores – the piece is pro forma, lovely Mozart, complete with an indefatigable supply of charming melodies to delight any and all listeners.

Try to savor the halcyon mood of the Mozart as much as possible, be cause towards Osiris and the “Manfred” Symphony could not be two more different works, both in terms of their affect and inspiration. Based on Egyptian mythology, Matthias Pintscher’s towards Osiris was commissioned by conductor Simon Rattle for a 2005 recording of Gustav Holst’s The Planets, released on the EMI Classics Label. Maestro Rattle’s aim was to have a group of living composers create a set of new works to pair with The Planets, which he dubs “The Asteroids”. Though there are no galactic connotations in towards Osiris, the piece does unfold like view a series of disconnected constellations, which eventually become more unified thanks to a gradually energizing percussion part.

Pintscher’s music is uncommonly brutal, an affect that makes sense in light of the myth on which the composer based the piece. In a documentary EMI produced as part of their recording project with Simon Rattle, Pintscher describes the Egyptian myth of Osiris wherein the God is torn into pieces that are ultimately collected and reanimated by his wife, Isis. Towards Osiris emulates this story with startling precision. As I already noted, the musical ideas are disparate and violent, seemingly representative of Osiris’ dismembered remains The percussion part is crucial to the motivation of the music’s activity, just like the flapping of Isis’ wings as she attempts to bring her deity husband back to life. In the end, the music surges with the increasingly active lifeblood of the percussion part and the once isolated ideas of the work’s beginning come together in one sonic mass.

Tchaikovsky’s “Manfred” Symphony is similarly based on an extra-musical program, though the connection here is a little more deliberate. The narrative on which Tchaikovsky based the work is an adaptation of the supernatural-themed poem “Manfred” by Lord Byron created by the Russian critic Vladimir Stasov. In turn, Stasov’s inspiration came from Hector Berlioz’s Harold in Italy, an enormously popular work in Russia for which Stasov imagined the “Manfred” Symphony as a sort of sequel. Tchaikovsky’s participation in the project came accidentally. Initially, Stasov wished to work with Mily Balakirev, but the composer refused and (thankfully) recommended Stasov approach Tchaikovsky, instead.

Like Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique, the “Manfred” Symphony represents its program through musical ideas, some clearer than others. The long, dark opening movement is meant to evoke the desolate condition in which we meet Manfred, walking alone through the Alps as an exile, searching for relief from his regrets and memories. Themes emerge to represent the characters in the story, Manfred and his love Astarte, but do no reappear under the conventional pretexts we often see in Tchaikovsky’s works, including the beloved fantasy-overture Romeo and Juliet. Rather, Tchaikovsky writes the “Manfred” Symphony with liberal formal ideas, focusing on the music’s dramatic character over traditional structural requirements.

To this extent, the “Manfred” Symphony is very much the Richard Strauss tone poems Don Quixote or Ein Heldenleben: large, multi-movement works conceived to highlight the facets of a detailed extra-musical narrative. Armed with an uncommon sense of thematic and formal freedom, Tchaikovsky’s score is unpredictable and compelling, reflecting the emotional turmoil of Byron’s Manfred with a wide palette of orchestral colors and a multitude of captivating melodies (the latter, of course, is something we always expect with Tchaikovsky). This colorful and dramatic personality is most obvious in the final movement wherein Manfred finds himself in an underground “Hall of Evil”. Symbolically, an organ enters and signals our hero’s glorious acceptance of death and the end of his torment (listen closely to the bassoons and cellos in the piece’s final bars and you may be able to hear a very obvious allusion to the final movement of Symphony Fantastique, a work Tchaikovsky must have greatly admired).

This Day in UMS History: New York City Opera , The Marriage of Figaro (Feb 13-15, 1991)

February 13-15, 1991

Power Center, Ann Arbor

New York City Opera

The Marriage of Figaro

Music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Libretto by Lorenzo da Ponte

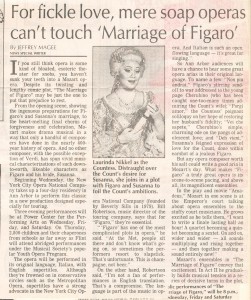

While Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro may be timeless, opera production sure isn’t. The program notes for this production of Figaro note that the company “features its popular and much-praised supertitles, an innovation in opera that clarifies all of the action onstage while preserving the integrity of the original language libretto.” Opera plots are complicated enough as it is without having to worry about reading the translations by the dim light in the theatre! And yet only twenty years ago, that’s exactly what audiences had to do.

The New York City Opera was founded in 1943 and, in addition to opera gems such as Figaro, has a repertoire of 273 works spanning five centuries of music and including 29 world premieres and 61 American and/or New York premieres of such notable works as Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle, Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Shostakovich’s Katerina Ismailova, Prokofiev’s The Love for Three Oranges and The Flaming Angel, Schoenberg’s Moses und Aron, and Glass’ Akhnaten. The company has been a leading showcase for young artists, helping to launch the careers of more than 3,000 singers, including UM alumnus David Daniels, Plácido Domingo, Renée Fleming, and Beverly Sills.

“This day in UMS History” is an occasional series of vignettes drawn from UMS’s historical archive. If you have a personal story or particular memory from attending the performance featured here, we’d love to hear from you in the comments.

This Day in UMS History: Debut of the Camerata Orchestra of Salzburg (Jan 20, 1978)

January 20, 1978

Rackham Auditorium

Camerata Orchestra of Salzburg

One of my personal favorite UMS concerts was the October 2008 presentation of violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter and the Camerata Orchestra of Salzburg with the complete Bach violin sonatas. Any orchestra that specializes in Baroque and Mozart, especially one from Mozart’s native town, has a pretty good spot in my musical pantheon. The Orchestra made its UMS debut in January 1978 with a performance of Handel, Boccherini, Mozart, and Vivaldi’s Concerto for Four Violins (as a violinist, I don’t think this piece is performed nearly often enough). The Orchestra was founded in 1952 with the original intention of specializing in Renaissance and Baroque music; it soon became evident that the orchestra had a special love for Mozart, and expanded its repertoire to include many of his works. The video above features a recent performance by Anne-Sophie Mutter with the Camerata Salzburg.

“This day in UMS History” is an occasional series of vignettes drawn from UMS’s historical archive. If you have a personal story or particular memory from attending the performance featured here, we’d love to hear from you in the comments.