Artist Interview: Actress Aisling O’Sullivan of The Beauty Queen of Leenane

Editor’s Note: University of Michigan student Zoey Bond spent several weeks with Druid Theatre Company as part of the UMS 21st Century Artist Internship program. The Company returns to Ann Arbor with a new production of Martin McDonagh’s dark comedy The Beauty Queen of Leenane on March 9-11, 2017. The interview below is with Aisling O’Sullivan, the Irish actress who plays the beauty queen of Leenane.

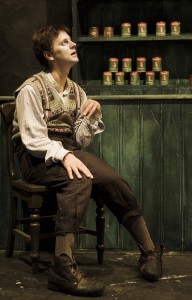

Photo: The Beauty Queen of Leenane’s Aisling O’Sullivan (left) and Marie Mullen (right). Photo by Matthew Thompson.

Zoey Bond: You’ve worked on playwright Martin McDonagh’s text before, what draws you to his writing?

Aisling O’Sullivan: It’s his characters, the dilemmas, and the wit, I suppose. It’s more than just the writing. It’s the delight I get from performing in the plays, which is so much fun to do and challenging. They are deep. They’ve got all of the colors.

ZB: As you know, this new production casts Marie Mullen in the role of the scheming mother. She won a Tony Award for the role of the daughter in the 1996 Broadway production. Last week you started wearing Marie’s boots in rehearsal, so you were quite literally stepping into her shoes. What has this part of the process been like?

AO: I found it very difficult. In the past, if I’ve seen a performance, and then I have to do my performance, I think I can do better. I don’t feel I can better than Marie. I saw her originally, and she is just extraordinary and really painfully beautiful. It would have been one of Marie’s defining performances. I’ve known her for a long time, so stepping into her shoes, I’m trying to embrace it and go, “Okay, so I’m privileged to be asked by the same director who thinks there is something I can do that might equal Marie. I’ll give it a shot.” I’m going to do something totally different, or I’ll just do what she did. I’m just trying to embrace the memory of her, and the joy that I got from it. So stepping into her shoes helps me symbolically with all of that. And her shoes are nice.

ZB: So then, the follow-up question is: After seeing the original production, has it been hard for you to create your own version?

AO: Yes. It’s difficult because of the way Martin’s work has to be rehearsed. You don’t get to do the scene over and over from start to finish without stopping. I have no idea who is developing in me until we start running the show. And then I’ll start getting the sense of who this person is. At the moment, it’s very much stop, start, stop, start, which is not conducive for me anyway. I tend to work through moods and energy shifts. I’m not getting the sense of that, which is not a problem. I’m very curious as to who’s going to appear.

ZB: What excites you about audiences seeing this today, 20 years later? What continues to be relevant?

A: Well, I think I love the universality of his darkness in relationships. I love that he puts it out there. It’s impossible not to recognize yourself in these desperate, almost psychopathic relationships.

For me, the play would be about owning your own power, or that if anyone ever encroaches on that space, you have to fight very hard to protect it. You’re in big trouble if anyone masters you — and I’m speaking here about the mother-daughter relationship. You’re in big trouble because you have no power. You’ve lost your own. And dark things can happen from that kind of powerlessness.

ZB: How do you think American audiences will respond to seeing this Irish play?

AO: I don’t know. I performed in front of an audience in America for the first time last year. And it was a very strange and scary experience for me because I’have spent 20 years performing to mostly English and Irish audiences. I can read them. If you get to know a species of audience, you can read them and you know how to play them. But with the American audiences, I had no idea of your taste and your comedy. It was a very interesting experience for me because it was unique. It was a totally different culture. I’m very interested in learning more about that. About how you respond, what’s your funny bone? What things move you?

ZB: In the play, do you have a particular scene, or a moment, or a line that you feel resonates the most with you?

AO: Not yet, but I love the humility, and honesty, and gentleness in a lot of these characters. They drop in these little, gentle sentences, and I think they are gorgeous moments for me to hear, as a performer in it, anyway. That it isn’t just razor-sharp.

ZB: How do you find the love in such a dark play? Do you think it is there?

AO: Definitely. It’s a funny thing that deep love can exist with masses of irritation. I irritate people too, I know that. As you get older, it’s less of a big deal. I’d be horrified to think I was capable of irritating anyone or boring anyone when I was younger, but now I’ve accepted that about myself. I think it’s all over the place.

ZB: Do you have a certain routine that you use to prepare for every role, or does it differ for each production?

AO: I don’t, but I’ll tell you what happened. I have been very instinctive until fairly recently, in that I would come completely open and unprepared to the first day of rehearsal. That was the way I worked and great things could come because I hadn’t made any decisions. Well, I worked on my first Shakespeare with this company last year. I was playing a fairly major part, and I’d never spoken a word of Shakespeare in my life.

I turned up one day, one big Bambi in the forest and the tiger Shakespeare stepped out of the trees. I was pretty much on stage for five hours speaking pure poetry and not understanding it. That was a baptism of fire, and since then, I try to come as prepared as I can be, in terms of learning the lines. I don’t have them off, but I know where they’re going, and then I come into the rehearsal space having done a bit of work. I think that makes me feel much more like an artist.

People who have gone to drama school are horrified listening to me going, “What? No preparation at all?” [Laughs]

ZB: So, there is a fine line between coming prepared and knowing enough, but not knowing too much, so that you can still discover.

AO: Yes. I think if you come in with some ideas, your mind has worked enough on it that you can change course. But if you come in with no ideas, you’re just going to accept the ideas that come to you. I think the crucial bit for me is to love the character. Even if you’re playing a psycho, to find something that you love.

ZB: That’s a good lead into my next question. With which parts of Maureen do you feel you identify?

AO: I identify with the weakness in her, the self-doubt, the way she tries to protect herself in her relationships. I see so much of me, and so much humanity, in her. That’s what is so brilliant about the play. Martin McDonagh was so young when he wrote it, and he just hit the seam of something about human beings that doesn’t often get shown.

Druid Theatre Company returns to Ann Arbor with a new production of Martin McDonagh’s dark comedy The Beauty Queen of Leenane on March 9-11, 2017.

Three patrons, three perspectives: The Cripple of Inishmaan

The Cripple of Inishmaan opened at the Power Center last night to rave reviews in the press and in the audience. Here, three distinct voices — a theater critic, a drama professor, and a student — give three distinct perspectives on the play. Read on for what they have to say and tell us: what did you think?

SALLY MITANI, THEATER CRITIC: To tell you the truth, I was all set to write something else. When you know you’re going to go ablogging at 11 p.m., it helps to have thought of a few possible directions ahead of time. But The Cripple of Inishmaan just surprised me with its straightforward simplicity and sweetness, so I tore up the notes. I’d never seen any of Martin McDonagh’s plays before but I’d read a bit about him and thought I’d caught his drift—edgy, ironic, the kind of guy that is a little scared to be caught looking like a sap. Scan his wiki and you’ll see: dark comedy, blah blah, black comedy, blah blah, ironic, black, dark, blah blah, works with Tom Waits and Christopher Walken. Check. Not that I have anything against this strain of art, but Cripple isn’t it. (Note to self: never use the phrase “dark comedy” again. Its currency has apparently been weakened to include anything that is sad and funny at the same time. At this rate we’ll be calling all of Chekhov a black comedy.)

SALLY MITANI, THEATER CRITIC: To tell you the truth, I was all set to write something else. When you know you’re going to go ablogging at 11 p.m., it helps to have thought of a few possible directions ahead of time. But The Cripple of Inishmaan just surprised me with its straightforward simplicity and sweetness, so I tore up the notes. I’d never seen any of Martin McDonagh’s plays before but I’d read a bit about him and thought I’d caught his drift—edgy, ironic, the kind of guy that is a little scared to be caught looking like a sap. Scan his wiki and you’ll see: dark comedy, blah blah, black comedy, blah blah, ironic, black, dark, blah blah, works with Tom Waits and Christopher Walken. Check. Not that I have anything against this strain of art, but Cripple isn’t it. (Note to self: never use the phrase “dark comedy” again. Its currency has apparently been weakened to include anything that is sad and funny at the same time. At this rate we’ll be calling all of Chekhov a black comedy.)

So forget “dark comedy,” whatever that means. It’s a sweetly brutal play about a small bunch of goofballs and gossips on a desolate, windswept western Ireland outpost in the 1930s. It strikes me as fairly representational of real life. I’d say “except that everyone’s much wittier than in real life,” but I’ve spent quite a bit of time in Ireland, and people there simply are wittier than in real life. We’re probably better at spatial relations or math or something, but, really, the Irish have some verbal skills that are uncanny. The Druid Theatre is marvelous, of course. Seeing them do this play is like seeing the Royal Shakespeare Company do Shakespeare or Comédie Française do Molière. They’re a Galway theatre company; the play is set in the Aran Islands, right out their back door. Druid’s the benchmark for how it ought to be done, so let’s not even waste any time talking about the quality of the production. (Except to say that it can be a bit of a strain to listen to all that dialect for two and a half hours. I had to take a breather once in awhile and, in fact, missed a few short chunks of the plot. I haven’t a clue why BabbyBobby beat up Billy—I was wandering around in my own brain for a minute, marveling at how much easier my version of English is to understand than the Druid Theatre’s, and suddenly poor Billy’s getting the tar beat out of him. You might have your moment like this too.)

It does also help to know about Man of Aran, even more so to have seen Man of Aran, which Martin Walsh (my fellow blogger here) was so wonderful to show this week at the Residential College. It’s a real-life early documentary made in the Aran Islands, around which the plot of Cripple revolves. And yet, it ultimately isn’t that important to the plot. I was going to rattle on about the complex relationship people in remote and beautiful places have with the people who anthropologize them, which I had surmised would be the theme here. That’s rich terrain, but it’s terrain that McDonagh more or less leaves alone, and instead he tells a sturdier, crueler story about a crippled boy. With jokes.

Sally Mitani is the theatre critic for the Ann Arbor Observer.

SARA BISCHELL, U-M STUDENT: In the world of Martin McDonagh, if one were to row up to the rocky shores of the Isle of Inishmaan, the first thing to greet the eye would be a giant, weather worn sign proclaiming “Welcome to Inishmaan: Where Honesty is the Best Policy.” It is that honesty, so brutal, and so endearing, that makes Martin McDonagh’s Cripple of Inishmaan such a beautiful piece of theater. Every character, from Billy the cripple’s elderly aunties to the pompous town gossip Johnnypateenmike (deficiency of space bar intended), at some point displays an incredible level of honesty. These characters say things that in our wildest dreams we wish we could say to our enemies, to our friends, and to that one person in town who just can’t seem to stop talking, and because we have all been close to that temptation, perhaps even succumbed to it, the laughter is inevitable as are the tears. McDonagh sends you on an undulating journey between these extremes.

SARA BISCHELL, U-M STUDENT: In the world of Martin McDonagh, if one were to row up to the rocky shores of the Isle of Inishmaan, the first thing to greet the eye would be a giant, weather worn sign proclaiming “Welcome to Inishmaan: Where Honesty is the Best Policy.” It is that honesty, so brutal, and so endearing, that makes Martin McDonagh’s Cripple of Inishmaan such a beautiful piece of theater. Every character, from Billy the cripple’s elderly aunties to the pompous town gossip Johnnypateenmike (deficiency of space bar intended), at some point displays an incredible level of honesty. These characters say things that in our wildest dreams we wish we could say to our enemies, to our friends, and to that one person in town who just can’t seem to stop talking, and because we have all been close to that temptation, perhaps even succumbed to it, the laughter is inevitable as are the tears. McDonagh sends you on an undulating journey between these extremes.

McDonagh also helps to humanize the characters by combining the brazen honesty with dialogue that becomes frequently repeated throughout the play. There are countless lines revolving around the same jokes, but somehow the delivery does not grow old. Rather, the repetition adds an element of comfort. During some of these awkward, often-cruel repartees between the characters, they toss in a joke that we have heard at least three times before, but it’s soothing in a way. The countless repetitions of references to Bartley’s fascination with telescopes, for example, eases the tension in the scene as Helen gives an unflinching description of how Billy’s parents died. The moment of humor injects the scene with hope and laughter, and in my mind I compared it to any one of the moments in my life where situations have gotten sticky and small blurbs of humor have broken down the barriers. Where theatrical comedy was concerned, the cast members had incredible timing, naturalistic but hilarious facial expressions, and the ability to transcend the boundaries that come between an Irish brogue and an American audience. They were phenomenal. The show was gut wrenching yet poignant.

And that is my honest opinion.

Sarah Bichsel is a sophomore at the University of Michigan majoring in English and Communications. She loves theater, music, baked goods, and well-made films.

MARTIN WALSH, U-M DRAMA PROFESSOR: I would rate The Cripple of Inishmann along with The Beauty Queen of Leenane as the best work of Martin McDonagh. Beauty Queen is the darker, more tragic of the two, but both share the playwright’s characteristic black comedy, intricate plotting, and rich ensemble of eccentric characters.

MARTIN WALSH, U-M DRAMA PROFESSOR: I would rate The Cripple of Inishmann along with The Beauty Queen of Leenane as the best work of Martin McDonagh. Beauty Queen is the darker, more tragic of the two, but both share the playwright’s characteristic black comedy, intricate plotting, and rich ensemble of eccentric characters.

Having taught a minicourse this semester on the plays and films of McDonagh, I have combed through most of the collected criticism on the playwright. Much of this is very positive, even enthusiastic, but there is a strong countercurrent which finds McDonagh’s work rather meretricious. These critics tend to see McDonagh as derivative, shallow, and manipulative, trading in cruel stereotypes of Irish rural people for the “hip,” well-heeled audiences of London or New York. (And, some of these critics assert, McDonagh isn’t even an Irish playwright in the first place.) Mc Donagh is faulted particularly for a lack of empathy for his creations who are reduced to grotesque puppets jerked about by a cynical and amoral puppet master. Some of McDonagh can feel like this. The Lieutenant of Inishmore, for example, seems constantly to want to top itself in transgressive humor and graphic violence in the manner of McDonagh’s master, Quentin Tarantino (ex. Inglourious Basterds).

This negative characterization of McDonagh is belied however by a play like The Cripple of Inishmaan which, in the capable and loving hands of Garry Hynes and the Druid Theatre Company comes across as both a finely crafted and a deeply felt piece of theatre. Our title character Cripple Billy is a truly complex figure superbly rendered by Tadgh Murphy. The victim of just about everyone’s casual verbal cruelty, Billy has his own mean streak. He’s as self-centered, manipulative, and callous as the rest of them. But his longing for escape, for some crumbs of affection; his quirky courage and persistence in facing his “host of troubles” win us in the end. Indeed all the characters, from the termagant Slippy Helen (a terrific Clare Dunne, sexy and repellant by turns) to the taciturn Babby Bobby (Liam Carney) have secret reserves of compassion which are occasionally allowed to seep up through the heavily crusted layers of boredom, frustration, and random cruelty that characterize this economically depressed community. Even the meddling, self-important newsmonger Johnny Pateen (Dermot Crowley) turns out to be something of a hero in the end. His supposed attempt, over several decades now, to kill his old mammy with strong drink actually seems more like its opposite – feeding her booze against doctor’s orders is probably preserving the batty ol’ thing for a second century. Add Billy’s “pretend aunties” Kate (Ingrid Craigie) and Eileen (Dearbhla Molloy), a delightful study in parental affection and early senility, with the inspired clowning of Laurence Kinlan as the perpetual adolescent Bartley, and we have a comic assemblage of characters as rich as anything in classic Irish or indeed world drama. The late “love scene” between Billy and Helen is as poignant and bitter-sweet as anything in Chekhov.

This fine Druid rendition of The Cripple of Inishmaan in what we might now call the “second generation” of McDonagh productions has convinced me that Martin McDonagh is not just the theatrical enfant terrible of the 90s but a playwright of lasting merit – and still funny as hell.

Martin Walsh is an Adjunct Professor, Department of Theater and Drama and Lecturer IV/Head of Drama Concentration, U-M Residential College.

Martin McDonagh on the Big Screen

Next week UMS welcomes the Druid Theater Company from Galway Ireland to Ann Arbor with their Martin McDonagh– scripted/Garry Hynes-directed play, The Cripple of Inishmaan. To say I’m excited is about as pointless as debating the delectability of that other magical Irish import Guinness! It goes without saying.

In advance of the performances, the U-M Residential College Drama Department is screening a few related films that we hope you can check out if you get the chance. All screenings will take place in the RC Keene Theater located in the East Quadrangle Dormitory and are free and open to the public.

Sunday, March 6, 7pm: Man of Aran

This 1934 documenty film by Robert J. Flaherty follows everyday life on the Aran Islands located off the coast of Ireland, and, at least partially, inspired The Cripple of Inishmaan which is set (at the time of the documentary’s filming) on the largest of the Aran Islands, Inishmaan. This screening will be preceded by a short performance from local Celtic music ensemble, Nutshell.

Tuesday, March 8, 7pm: Six Shooter and In Bruges

Although he might be better known as a playwright, Martin McDonagh also wrote and directed two films: the live action short, Six Shooter (2005, 27 minutes, Rated R, starring Brendan Gleeson, Rúaidhrí Conroy, and David Wilmot), and the full-length feature, In Bruges (2008, 107 minutes, Rated R, starring Colin Farrell, Brendan Gleeson, and Ralph Fiennes).

Six Shooter, his first film, won the 2006 Oscar for best live-action short. This black comedy follows a man named Donnelly (Brendan Gleeson), whose wife has just died, on an increasingly bizarre train ride in Ireland [in which] he meets a young couple whose infant has also just died, and a nameless young man with a warped sense of humor and an explosive secret (synopsis from the New York Times).

In Bruges, the opening night film of the 2008 Sundance Film Festival, is a black comedy crime film starring Colin Farrell and Brendan Gleeson as hitmen in hiding, with Ralph Fiennes as their gangster boss. The film takes place and was filmed in the Belgian city of Bruges. Colin Farrell won a Golden Globe Award for Best Actor in a Musical or Comedy for the film, while Martin McDonagh won a BAFTA Award for Best Original Screenplay. You can view the trailer below.

UMS Staff Picks: The Cripple of Inishmaan selected by Sara Billmann, Director of Marketing & Communications

SN: The multi-award winning Druid and Atlantic Theater co-production of Martin McDonagh’s The Cripple of Inishmaan has been described as “a break-your-heart, cruelly funny evening” – what kind of theatrical journey can audience members expect to experience when they see this production?

SB: I don’t want to spoil the story, but suffice it to say that it will be quite an emotional ride.

I’ve seen two of Martin McDonagh’s plays when they were produced in New York in the mid-late 1990s, and they are simply brilliant pieces, in part because of the way they force you to re-examine your own morals. He sets up these outrageous scenes that are absolutely hilarious, then delivers the knock-out punch that makes you realize you’ve been laughing at something that is, in fact, incredibly tragic. The June issue of <i>Opera News</i> put it perfectly: “As anyone who’s ever sat through a Martin McDonagh play can attest, sometimes the only response we can muster when confronted with the searing emotional or physical pain of others is a laugh.”

I read this play poolside while visiting my in-laws in San Antonio and found myself laughing out loud on any number of occasions. Let’s face it, there are many plays where you chuckle inwardly, but something that produces a spontaneous outburst while reading to yourself is extraordinary in its own sense. And based on every production I’ve seen of McDonagh’s work, the live production will far exceed what’s on the page.

So that we could all familiarize ourselves with the play, about a dozen members of the UMS staff did a “read-through” this summer. I hope that some audience members will be interested in doing the same — we’d be interested in putting together play-reading groups for others and loaning the scripts. It’s a great way to familiarize yourself with the dialects and turns of language that really bring the piece alive. And, of course, a great way to meet new people too.

SN: What are you most looking forward to about this UMS debut performance?

SB: It’s pretty simple, really – I just can’t wait to see what they do with the production to bring it alive. I have friends who saw this production when it was on Broadway a few years ago and raved about it. Having grown up in a small town, I recognize some of the quirky characters and look forward to seeing how they are realized on stage.

SN: What other events are on your “must see” list for the 10/11 season?

SB: Just about everything! As a trained classical musician, I’m particularly interested in the big orchestras and piano recitals. I was turned on to Denis Matsuev about two years ago by someone who had heard his recording in Gramophone magazine. His playing is really quite extraordinary. I also adore Schubert and am looking forward to the three Tákacs concerts, as well as the Scharoun Ensemble performance of the Schubert Octet. I’m also looking forward to Grupo Corpo – what a great company! I could go on and on. The beauty of being the marketing director for UMS is that I start to research all of the artists we’re presenting long before we announce the season, and I always get turned on to things I never would have thought I’d enjoy…which ultimately means that the entire season becomes a “must see” for me.

SN: What do you enjoy doing outside of work?

SB: I have two kids – Elisabeth is 8 and going into 4th grade, and Harry is 6 and going into 1st grade – who keep me plenty busy. I was about to respond that I do laundry outside of work, until I saw the word “enjoy” in the question. Elisabeth loves to play baseball, so I think I’ve spent the better part of July attending her games and taking her to see the Tigers when time permits. I’m also hopelessly addicted to The New Yorker and steal moments here and there to try to stay caught up. Other hobbies include wine tasting and walking the dog – we acquired a boxer/pointer mix from the Humane Society three months ago, and I’ve become the family’s designated dog walker, which fills up a shocking amount of time each day.

SN: What have you been listening to on your iPod?

SB: Ha! The day I get to listen to my iPod will be a great day indeed. Lately my kids have been torturing me, making me listen to “Stayin’ Alive” and 1980s dance tunes (oh, to return to the days when my daughter would watch “The Barber of Seville” by choice…). But when I can wrestle it away from them, I mostly listen to Schubert lieder, Maria Joao Pires performing Schubert and Chopin, Denis Matsuev playing Rachmaninoff, and Mahler, though truth be told, the iPod doesn’t do Mahler justice. Murray Perahia‘s recital in 2000 of the Bach/Busoni Chorale Preludes and the Goldberg Variations will always rank among my top UMS performances, and I often bring back that memory with the recording “Songs Without Words” released around the same time. Angelika Kirchschlager and Fritz Wunderlich are among my favorite singers, though I will confess that I also enjoy Pink Martini in my less serious moments. And I recently loaded on a CD by a wonderful Iranian group called Ghazal.