The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess and the Quest for American Opera

This essay is written in conjunction with The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess. UMS Presents Opera in Concert: The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess Saturday, February 17th at Hill Auditorium in Ann Arbor.

“The Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess and the Quest for American Opera” is written by Mark Clague, the Editor-in-Chief of the George and Ira Gershwin Critical Edition.

Photo: Porgy and Bess. Courtesy of Ira and Leonore Gershwin Trusts.

For me, the opera Porgy and Bess (1935) is about resilience, about a community’s hope for a better future despite the cruel evidence of experience. Catfish Row amplifies the struggle of American society with racial injustice, poverty, sexism, addiction, sexual violence, natural disaster, murder, and the divisions of society into north and south, sacred and secular, black and white. I wish that performing this very human drama—written and premiered more than 80 years ago—was simply an act of remembrance. I wish that it served only as a reminder of a past forgotten at our peril, of inequities and diseases vanquished, of civil rights heroes who, responding to injustice across the nation, bravely confronted and solved these very American problems. If this were true, Porgy and Bess would celebrate a transcendent human spirit while serving as a warning about an era that should never return. Unfortunately, Porgy and Bess is not simply a memory, but a living document. The injustices it confronts remain.

It is thus with tragic intensity that in 2018 Porgy and Bess still expresses a potent and contemporary urgency that resonates with our everyday lives. The opera’s plot is propelled by the bias of white law enforcement—false accusations, facile assumptions, a rush to judgment in the absence of real justice—while today black men in America are disproportionally killed by the police. In Act II, a hurricane kills most of the men of the fishing village, while stealing both mother and father from an infant in whom hopes of a bright future had been placed. This past year in the U.S., three major hurricanes—Harvey, Irma, and Maria—hit American shores, making the storm’s warning bells in the opera that much more potent. When Crown attacks Bess during the Kittiwah Island picnic, it recalls the growing list of accusations of sexual misconduct in today’s news. At the end of the opera, addiction enslaves Bess to a life of prostitution, while in 2016 opioid addiction killed more than 20,000 Americans. In facing these issues, performing Porgy and Bess offers an opportunity for dialogue—not just about the past but about the present.

The insidious danger of Porgy and Bess as a cultural monument is that its black characters can be interpreted as caricatures, not dramatic personae. In a society in which whites are privileged and blacks are not, the enthralled listener to Gershwin’s music can experience Catfish row uncritically. Crown can be seen not as a troubled contradiction caught in a desperate cycle of survival and addiction, but as a stereotype reinforcing white fears of black violence. Read in racist terms, the poverty of Catfish Row becomes emblematic of black (in)capability rather than a depiction of a community of working class strivers facing a mountain of unequal opportunity.

To sponsor a performance of Porgy and Bess, then, is to take on the responsibility for contextualizing and informing the opera’s audience of both its racist dangers and its artful activism.

As a white man leading the Gershwin Initiative at the University of Michigan, I have struggled with the meaning of preparing the score of Porgy and Bess for posterity. What is the opera’s legacy? I admit that in 2013, when we began work on the new score only months after the re-election of the United States’ first black President, the question seemed all but answered. Today the question is again potent. On one hand, I, too, am enchanted by George Gershwin’s music, Ira’s words, and the Heyward’s story, which combine to forge what for me is the opera’s very human expression of passion, pain, and possibility. I was further driven by personal loyalty to my fellow scholar, Wayne Shirley, as I want to help bring his virtuoso feat of scholarly editing to print.

Yet, ultimately, the answer to this question cannot be mine. I am sensitive to the call from former U-M professor Harold Cruse (1916–2005) asking black artists of the 1960s to boycott Porgy and Bess. As described in his 1967 book The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual, Gershwin’s opera was “a symbol of that deeply engrained, American cultural paternalism” that obscured black artists’ originality in “Negro theatre, music, acting, writing, and even dancing, all in one artistic package.” For Cruse, the success of Porgy and Bess became a barrier to the realization of other new works of black authorship.

Photo: Porgy and Bess. Courtesy of Ira and Leonore Gershwin Trusts.

The way out of this paradox of appropriation is to democratize the controls of cultural production such that African American writers, lyricists, and composers can tell their own stories. And it cannot stop there. #OscarsSoWhite must give way to more than Selma, Moonlight and Get Out. The theater must go beyond Hamilton. Works by women, Latin Americans, Native Americans, Asian American—any and all authors—deserve a chance to thrive on their artistic merits and message.

Studying Porgy and Bess has convinced me that its all-white creative team, while writing from their own necessarily limited perspective and experiences, saw the opera as an opportunity to bring the talents of black artists to the cultural mainstream. Their activism—if it can be called that—balanced entertainment with a focus on an American experience typically excluded from popular production. While African American composers such as Scott Joplin, Harry Lawrence Freeman, and James P. Johnson had written operas about the black experience before Porgy and Bess came on the scene, the celebrity of George Gershwin was necessary in 1935 to bring the story of black America to Broadway. That the composer turned down a $5,000 commission from New York’s Metropolitan Opera (about $100,000 in today’s dollars), in order to avoid the use of white choristers in blackface, speaks to the composer’s own growth since the failure of his 1921 blackface musical drama Blue Monday.

Countless musical moments in Porgy and Bess speak to the Gershwins and Heywards’ respect for black creativity. The composer spent nearly ten years preparing for the work, after reading DuBose Heyward’s novel Porgy in 1926. Gershwin’s creative gifts were so facile that such a period of study and preparation was unprecedented in his professional life. He seemed to know that Porgy and Bess would be the most challenging project he had yet faced.

The lullaby “Summertime” is the first aria heard in the opera. It gives voice to the dreams of a mother for her child. The beauty of its first note—a difficult entrance, soft and high in the soprano’s tessitura, belies the challenges facing Jake and Clara’s newborn son. The song’s hope and soaring lyricism serves as a tragic foil that foreshadows the loss to come, yet its endless melody is also the seed of the resilience that will allow Catfish Row to carry on after tragedy.

Gershwin did not quote African American music in Porgy and Bess verbatim, but created original music that evokes its style and sensibilities. His music draws from the performances of Cab Calloway in New York, and especially from the music of the Gullah people, who lived on and around the Georgia Sea Islands near Charleston, South Carolina, where the opera is set. Gershwin resided on one of these islands—Folly Island—for a month in the summer of 1935 to experience its soundscape. Echoes of his research can be heard throughout the opera, as when Robbins is killed and his wife Serena sings “My Man’s Gone Now,” an intimate cry of love lost and dreams thrown into disarray. In response, the Catfish Row community rallies to support his widow and their children, mirroring their devastation in the spiritual-like anthem “Gone, Gone, Gone.”

The paternalism of which Cruse complained is evident in the Heywards’ introduction to the play Porgy, upon which the opera’s libretto is based. However, it also reveals the playwrights’ excitement to invite black actors into a collaborative process in which they would contribute their own creativity to the storytelling. In fact, the vendors’ cries—selling deviled crab, honey, and strawberries—were not part of the original novel, but instead were added to the text by the black actors themselves to increase the drama’s realism. In the opera, singers can steal the show with these evocative calls. The Strawberry Woman and Crab Man’s rising slides give voice to the day-to-day struggle for existence with virtuoso power and emotional eloquence. The collaborative legacy hidden in these moments between art and artist continues to nourish the opera as a whole today, as a new generation of singers bring their own talents, character research, and emotional understandings to some of most demanding and artistically challenging vocal roles in all of opera’s repertory.

Photo: George and Ira Gershwin and Dubose Heyward. Courtesy of Ira and Leonore Gershwin Trusts.

Finally, Porgy’s climactic expression of duty in the face of the impossible—“Lord, I’m On My Way”—fulfills for me the essential message of DuBose Heyward’s novel and the newspaper clipping that served as its inspiration. Heyward had read a brief notice in a Charleston paper about Samuel Smalls, a local character and disabled beggar known as “Goat Sammy.” Smalls was apparently wanted by the police on the charge of attempted murder, and, for Heyward, the thought that a black man, crippled both physically and economically, could be so bold as to attempt to take another’s life seemed the inspiration for a powerful story. Born and raised in Charleston, the writer changed “Sammy” to “Porgy,” resulting in the 1925 novel. It is a tale of the transformation of a weak beggar into a determined, strong, and dynamic force.

Prior to studying Heyward’s novel, the ending of Gershwin’s opera always left me disappointed. Gershwin’s optimistic music seemed to say it was possible that Porgy could find Bess, but I heard Porgy’s determination as delusion. Now, it seems to me that the opera is really the tale of Porgy’s transformation. He begins the opera as a smart, but impotent survivor who scrapes subsistence from coins dropped by sympathetic passersby. By the end of the opera, he has defeated Crown—the opera’s symbol of ultimate strength and manhood—inheriting his mantle. Thus, I have come to see Porgy’s determination to rescue Bess not as fantasy but as his newfound duty, whatever the odds. Catfish Row, too, moves on. The community itself may, in fact, be the true hero of the opera. Its heroism lies in its resilience, the inevitability of its resolve to continue in the face of repeated tragedy.

I find this same resilience in the opera itself. Porgy and Bess is a survivor. While Gershwin’s early death two years after the opera’s premiere made Porgy and Bess the heartbreaking finale of an American creative legacy, the composer certainly never intended this work to mark an endpoint. His folk opera was just another waystation on a creative journey, an improbable quest to create a credible American contribution to a European art form, using Broadway song and African American spirituals as musical inspiration. Gershwin hoped to forge a distinctively American music that gave voice to his age, with all its promise and problems. That quest does not end with Porgy and Bess.

This essay is written in conjunction with The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess. UMS Presents Opera in Concert: The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess Saturday, February 17th at Hill Auditorium in Ann Arbor.

“The Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess and the Quest for American Opera” is written by Mark Clague, the Editor-in-Chief of the George and Ira Gershwin Critical Edition.

Happy 200th Anniversary, Star-Spangled Banner!

Photo: Conductor Jerry Blackstone and University of Michigan students rehearse “The Star-Spangled Banner” in advance of their concert at Hatcher Library.

September 14, 2014 marks the 200th anniversary of the U.S. national anthem “The Star-Spangled Banner.” It’s amazing to me that the date is here! My own fascination with the anthem grew out of my teaching of an almost annual course on American music. The first class in this course always focused on the question of what an explicitly “American” music might be and why (if at all) national identity might be important. In hopes of forging a connection with my students and getting a great discussion going, I began using the U.S. Anthem as a vehicle to consider the question of national identity in music. All of my students have some relationship to the song, whether they grew up singing it in school or even if they are an international student visiting the University to study who is struck by the unusual prominence of the song in American life.

I often play Jimi Hendrix’s Woodstock Anthem as part of this session, but wanted to showcase a recording of the original song Key used as a melodic vehicle for his lyric—“The Anacreontic Song”—as well as of the first version of “The Star-Spangled Banner” in full 1814 style. It surprised me that I couldn’t find either. So, since this is the University of Michigan and we had ready access to a great recording venue and incredibly talented student musicians, we made our own! My colleague Jerry Blackstone, who conducts the UMS Choral Union among his duties directing choral music at the University as a whole, signed on as a collaborator and took the project to a new artistic level.

Our recordings are now published as part of a two-CD set titled Poets & Patriots: A Tuneful History of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” It has been featured by the Smithsonian, The New York Times, C-Span, Encyclopedia Britannica and others and its related videos have been viewed over 55,000 times on Youtube. Just today the Library of Congress released its video of the July 3, 2014 recital by Thomas Hampson that features our music. It was a lifetime thrill to be joined by University of Michigan alumni singers and to be able to present my research with Hampson at the Library’s Coolidge auditorium. Pretty good for a class project!

Jump to 6:12 for Mark Clague and Thomas Hampson:

As I continued to do research, I found the story of America’s Anthem to be ever more fascinating. Its bicentennial offered the further opportunity to share my love of the song and its story more widely. For me, the story of “The Star-Spangled Banner” is the story of American democracy in action. It’s also about the vitality of music in our lives. The anthem is more than a song; it’s a sounding board that helps us figure out who we are and who we want to be.

University of Michigan Events & Live stream

You can learn more about the song through a whole series of campus events at the University of Michigan this fall, beginning this weekend with #Anthem200 celebrations as part of the Michigan Marching Band halftime show and a 1-hour grand opening recital at the Hatcher Graduate Library on Sunday, September 14 at 4 pm. (It’s just before you head to Hill Auditorium to hear Itzhak Perlman at 6 pm). Attend the events in person, or watch online via live stream.

I truly hope you’ll be able to visit the U-M Library exhibit which features items from U-M’s incredible collections, especially the William L. Clements Library which preserves (and thus we will display) one of only a dozen surviving copies of that original 1814 sheet music edition that started our whole project.

Other Star-Spangled Banner Resources

Complete listing of events at the University of Michigan

U-M American Music Institute

StarSpangledMusic.Org

The Heart of History: Reconsidering the Great American Songbook

Editor’s note: Looking to hear selections from The Great American Songbook live? Audra McDonald performs on September 15, 2013.

Photo: Ira and George Gershwin, Beverly Hills, 1937 (Ira and Leonore Gershwin Trusts (used by permission).

If a nation kept a diary, it would be in its songs. Song is where poetry meets praxis, where the imagination hits the dance floor and the ineffable finds expression in the everyday. Verse envelops life’s detail to offer both prosaic insight and poetic pleasures; yet, in song, music expands the emotional richness of lyrical syntax, transforming words into dreams, disappointments into wisdom. Cast in the delight of melody, harmony, and rhythm, song thrives even without specific meaning. In lyrical enigma resides possibility, whether in Schubert’s Lieder or on Top 40 radio, song’s ambiguities invite association to make the popular deeply personal. Some becomes “our song,” as music collides with living. These human riches of song may well transcend time and place, yet song is equally historic, preserving ideas and events that forged a path to the present.

In the United States, entries in the Great American Diary of Song include ballads by a signer of the Declaration of Independence—Francis Hopkinson—and spirituals that tell of the strengths, sufferings, and hope of African American slaves. The legendary songwriters of Tin Pan Alley, of Broadway, of Hollywood strove for hits to catalyze immediate commercial success, yet surprisingly often they created classics that captured the concerns, optimism, and challenges of the times. Irving Berlin’s “Puttin’ on the Ritz” (1929), Yip Harburg and Jay Gorney’s “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” (1932) and “Over the Rainbow” (1939) by Harold Arlen and Harburg explore fundamental human themes while they articulate a time of traumatic change from exuberance to Great Depression and its aftermath in American history.

The Gershwin brothers had a particular knack for catching the spirit of the age and for all time. Their many love songs, such as the unknown gem “Ask Me Again” (rediscovered by Michael Feinstein and finally introduced to the public in a 1990 production of Oh Kay!), offer more than tales of heart meets heart, they tell of the everyday as universal—here in the nervous and joyous first blush of infatuation and the dreamy ideals of romance. “Fascinating Rhythm,” in contrast, merges the energy and optimism of the Twenties with its explosive cultural tension that marks jazz as the signal success of Harlem’s artistic renaissance and its quest for Civil Rights. Or maybe it’s the iconic lullaby “Summertime” from Porgy and Bess, arguably the most frequently recorded song in audio history (in competition with only Paul McCartney’s “Yesterday”) and one now forever associated with beloved UMS artist Audra McDonald in her 2012 Tony Award winning performance as Bess. The Gershwins’ creative strength is on vivid display in each rendition; their songs grow ever richer through the artistry of countless performers and performances.

It is thus with both great excitement and equal humility that the University of Michigan’s American Music Institute at the School of Music, Theatre & Dance announces the George and Ira Gershwin Critical Edition. Created in partnership with the Gershwin family, this all-new series of publications will — for the first time — bring the rigor of scholarly editing to the realization of the Gershwins’ musical legacy. On the stages of Hill Auditorium, Britton Recital Hall, and Power Center, faculty artists and student performers will bring their interpretive energies to the Gershwins’ work to inform and refine the editorial process. The project as a whole will inspire a range of courses, talks, and research examining the cultural contributions of the Gershwins in context of a broad accompanying transformation of American life, from the Victorian Age through the Jazz Age up through today.

Video: Audra McDonald sings “Summertime” from The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess.

An encyclopedia never to be finished, the Great American Songbook has much to say about the past as well as the present, making it a vital locus for research and study as well as performance on campus and in the classroom and on campus. Song does more than entertain, it celebrates, it informs, it heightens the moment as it encodes ideology for analysis. Most importantly, song gives history a heart. Whether given voice in the interpretations of the art’s great singers, or by a raucous chorus of kids in the family car, song recruits the beauty of the ages as a tool for understanding, here and now.

Tweet Seats 3: Mariinsky Orchestra of St. Petersburg

Editor’s note: This season, UMS is launching a new pilot project: tweet seats. Read the complete project description and pre-interviews with participants

For the third tweet seats event, we saw the Mariinsky Orchestra of St. Petersburg:

This week’s participants:

- Paul Kitti, writer for iSPY magazine

- Mariah Cherem, Production Librarian at Ann Arbor District Library

- Mark Clague, U-M Associate Professor of Musicology and UMS Board member

- University of Michigan social media intern Taylor Davis

Read the whole tweet seats conversation.

UMS: How did tweeting affect your experience of the performance? Did you expect this effect or are you surprised by this outcome?

Mariah Cherem: At first, I did feel awkward tweeting. I felt that it took me out of the moment a bit, and removed me one more step as observing my experience in a different way. As the performance went on, there were times when I felt completely comfortable tweeting, and other times when I frankly just wanted to let go of that way of thinking because I didn’t have much (more) to say.

UMS: If you’ve participated in prior tweet seats, how did tweeting at this performance compare to tweeting at Aspen Santa Fe Ballet or at Rhinocéros?

Paul Kitti: Tweeting the orchestral performance had less of an effect on my experience than it did during the Aspen Santa Fe Ballet and Rhinocéros. It was less interruptive and I felt it didn’t take away from the experience, because I didn’t need to have my attention on the stage the whole time. It felt natural because I’m used to being on social media while listening to music.

Mark Clague: As I could hear the orchestra even while looking at my cell phone’s screen, I found tweeting the concert less disturbing than tweeting for the dance and theatre events I had experimented with previously. The sold-out audience for Mariinsky also provided an exciting atmosphere. There was more Twitter dialogue at the intermission and afterwards from friends and current students–maybe a result of the larger seating capacity of Hill Auditorium and this added to the fun for me. There was also a bit of debate about the concert and which piece was played most expertly. Several people I know who didn’t tweet were clearly following the feed and commented to me about it face-to-face encounters the next day. I did receive one disapproving Tweet response from a follower who objected to my picture of the orchestra (assembling and not taken during the performance) as a violation of decorum. The august traditions of great music in our concert halls may prove discouraging to new media. In some ways, tweeting orchestra concerts seems like the perfect entry point for social-media enabled conversations to start (since one does not have to “see” the stage constantly to experience the art fully), but on the other hand the formal nature of our classical concert rituals might make it difficult to sanction change. I wonder if Hill wouldn’t be the perfect location for an intermission tweet exchange in which all patrons were encouraged to discuss a performance during the interval and/or immediately after a performance. Because of the large seating capacity, there are likely dozens with active Twitter accounts who might want to sign on. The screens showing the stage in the lobby could instead post the twitter feed to share the discussion more broadly.

UMS: How did you feel about tweeting in Hill Auditorium?

Paul Kitti: Because I was tweeting in Hill Auditorium, I was seated in the very back row of the balcony. The place is beautiful and I got to take it all in from this perspective. I felt a considerable distance from the performance, however, and – added to the fact that I was tweeting and relaying information to the outside world – it kind of put me in suspension rather than feeling connected to the music.

Mariah Cherem: Hill is a gorgeous venue – from both a visual and auditory standpoint. It was great to be able to hear so well even in the very back corner row. I wish that I had been able to take my phone out of the box to capture more of the visuals. I should have captured some visual detail/close-ups for twitter/instagram during intermission, but frankly I was too focused on getting in a quick break!

Stay tuned for the next tweet seats event: Gilberto Gil on Saturday, November 16.

How do you feel about using technology during live arts experiences?

Tweet Seats 2: Théâtre de la Ville: Ionesco’s Rhinocéros

Editor’s note: This season, UMS is launching a new pilot project: tweet seats. Read the complete project description and pre-interviews with participants here.

For the second tweet seats event, we saw Théâtre de la Ville: Ionesco’s Rhinocéros:

This week’s participants:

- Paul Kitti, writer for iSPY magazine

- Greg Baise, Detroit-based concert promoter, arts writer, and DJ

- Leslie Stainton, U-M School of Public Health Findings magazine editor and umslobby.org contributor

- Mark Clague, U-M Associate Professor of Musicology and UMS Board member

- University of Michigan social media intern Mollye Rogel

- Michael Kondziolka, UMS director of programming, scheduled to tweet at this event, was not able to participate. See his note about why below.

Read the whole tweet seats conversation here.

UMS: So, how did tweeting affect your experience of this performance?

Paul Kitti: For this particular performance, tweeting was most often on the back burner for me. It was impossible to tweet without missing something, as the performance was in French with surtitles (and I only know about three words in French…) The outcome, which I expected, was that I enjoyed the play as well as the twitter conversation, but the dialogue I missed in the process left some holes in the experience.

Greg Baise: I found myself thinking of tweets, but waiting for lulls to post them. Some tweets got away because I was deep into the play. Initially I was concerned that my tweeting activity would be a distraction to others. It turns out it was more of a distraction to myself!

Mark Clague: I was surprised by the conversational quality of tweeting Rhinoceros. Since we were reacting to a provocative narrative characterized by inference, juxtaposition, and an epic sense of language that seemed immediately referential and symbolic, many of the tweets searched for meaning. I paid attention to the hashtag and responded to several of the other tweet experimenters, but also to a couple of friends who either attended or just reacted to my observations. One such interchange led to a couple rounds of comments and ultimately intractable disagreement in interpretation. I found myself musing on the disagreement for days afterward and discussing the show face-to-face with another friend to clarify my own understanding. I didn’t change my mind and still prefer a more open interpretation connected to contemporary events, but my commitment to that understanding is richer and deeper for the tweets. Another thing I liked is that a question occurred to me the next day and I could tweet @UMSNews to get my question answered — YES, the set was transported from Paris to Ann Arbor. Finally, I attended the play a second time the next night and did not tweet. My experience was different — I became aware of how many people were speaking French in the audience. I don’t speak French, but gradually improved my understanding of the actors as the play progressed. Also, I sat in row 8 or so close to the stage, rather than tweeting from the back of the balcony. The emotional intensity of the play was much higher sitting so much closer. I was engaged both nights: the first felt a bit more intellectual (tweeting the show in this situation felt like taking notes at an exciting lecture) while the second was more raw and emotional. I’m guessing that my experience on night #2 was richer for having “researched” the play the evening before.

Leslie Stainton: If anything, this second experience of tweeting only confirmed my earlier antipathy to the form (if that’s the right word). It probably didn’t help that I saw the show near the end of the work week and after a glass of wine, so the dim lights and French dialogue and stratospheric tweet seats combined to send me into a bit of a nap. I felt oddly detached from the performance, and I suspect part of that had to do with the isolation I now associate with tweeting live theater. You’re apart from the crowd, with your little black box and too-bright phone. The production itself was gorgeous, provocative, beautifully acted, deeply meaningful. Some of this came together for me at the end, when I really did wake up with a “pow” and suddenly wished I could see it again, without the filter of tweets, and certainly from a better seat than the ones we had. (Didn’t bother me nearly so much with Aspen-Santa Fe, but this production needed to be seen up close, I think.) What “stuck” from the experience is my realization that I don’t want to tweet again–as I said to someone on my way out, I’d prefer to keep my brain farts to myself next time. But thanks for the experiment, and thanks to UMS, as always, for going about this so intelligently and carefully. And thanks for making it possible for those who DO get something out of this medium to keep at it.

Michael Kondziolka: I bailed on my commitment to be a tweet seater last night. Not because I didn’t want to try it out, but because if became clear that the General Manager of Théâtre de la Ville and the US tour producer of Rhinocéros wanted to sit with me at the opening night performance. I didn’t want to run the risk of offending anyone by creating a moment of “cultural misunderstanding.” After the show, I mentioned this to them both and they were, not surprisingly, first a little put off by the whole notion of tweet seats and, after more conversation, intrigued. I shared the tweet stream with them…and they seemed to like it. Interestingly, there seems to be very little commitment or conversation at the moment in Paris around the role of social media in connecting with audiences OR in building or attracting new audiences. At least this seems to be the case at TdlV. The GM of TdlV wanted as much information on the topic as I could give him…clearly he knows that he needs to look at these issues very seriously. Imagining what the experience of tweeting during last night’s performance would have been like gives me a rash. The complexity of the show…the layers of meaning and metaphor embedded in the text….how that meaning is delivered through the force of the acting and physical performance…PLUS the reading of super-titles (my French is only so-so)…was a lot to take in and make sense of from time to time. The idea of another layer — the processing of my thoughts and experiences and transmitting them in real time on a little illuminated keypad with my thumbs in real time — might have sent me around the bend. But I am still willing to try at an upcoming show!!

UMS: What do you think makes for a performance “sticky” (the performance “sticks” in your memory months or years later)? Do you think live tweeting a performance make it more or less likely to be “sticky”?

Molly Roegel: The quality of a performance in terms of acting, directing, music and set design, makes it “sticky” for viewers, as well as the relevance to them and how much they can personally understand. Live tweeting made this performance far less sticky to me as I could not pay attention to the subtitles, Instagram, Twitter, and the actual performance in any sort of way that would have allowed me to get the full experience of the play. I greatly enjoyed live tweeting but it was definitely not conducive to gaining the full scope of the play.

Mark Clague: Tweeting Rhinoceros has certainly made the experience more memorable or “sticky” for me. Four days later I can remember specific lines of dialogue and the emotion of the play remains vivid. I’ve had several conversations about the play with friends inspired by my twitter exchanges and reviewed my tweets archived on Twitter.com to review the performance, which reminded me of several personal responses that had begun to fade. Tweeting the show is definitely a source of distraction — I’m watching my cell phone screen at times rather than the stage. However, it’s not like I avoided all distraction the next night when I wasn’t tweeting on assignment. For the most part, I found that tweeting enhanced my attention and put me in a mindset to parse and understand the show. If the purpose of art is to get us to think and to think in unexpected ways, Twitter seems (for me at least) to serve this goal. If tweeting an art experience were to become more routine and typical, I wonder if some sort of compromise that takes the best of both my night 1 & 2 experience would be possible. One could tweet intermittently and engage with a broader conversation as the show inspired it. The brevity of Twitter leads to an immediacy and directness that might balance emotional reaction with analytical understanding.

Stay tuned for the next tweet seats event: Mariinsky Orchestra of St. Petersburg on Saturday, October 27.

How do you feel about using technology during live arts experiences?

Tweet Seats 1: Aspen Santa Fe Ballet

Editor’s note: This season, UMS is launching a new pilot project: an experiment at the cross-section of live performing arts and technology commonly known as “tweet seats.” Read the complete project description and pre-interviews with participants here.

For the first tweet seats event, we saw Aspen Santa Fe Ballet:

This week’s participants:

- Leslie Stainton, U-M School of Public Health Findings magazine editor and umslobby.org contributor

- Paul Kitti, writer for iSPY magazine

- Mark Clague, U-M Associate Professor of Musicology and UMS Board member

- University of Michigan Director of Social Media Jordan Miller

Read the whole tweet seats conversation here.

UMS: How did tweeting affect your experience of the performance?

Paul Kitti: Tweeting about the performance to people I knew weren’t in attendance made me more conscious about not only how I was perceiving the experience, but how others might. I also feel if I hadn’t been actively thinking about things to say about what I was seeing, I would have viewed it more passively – almost as if in a trance. I think it was a good thing to be viewing the performance analytically, but at the same time, it somewhat took away from the dreamy, ethereal effect of the ballet.

Mark Clague: I was looking forward to the performance with added anticipation knowing that I’d be participating in the Tweet Seats experiment. For me, the result was positive in that it focused my attention into distilling my experience into pithy statements that could be shared via Twitter. There certainly were times when I had to check out from watching the dance to attend to writing a tweet, although as it turned out, I think tweeting could easily have been limited to the breaks between dances. I did feel a bit uncomfortable tweeting, knowing that I was “breaking the rules” of typical concert behavior and that the glow of my smart phone’s screen on my face might distract others. This distraction factor would seem to be maximized in theatrical presentations and dance where the audience is in complete darkness and the stage is lit with colored lighting and other effects that are vital to the aesthetic of the performance. Dance / theater must be watched so it prompts the question of whether an instrumental concert might be more hospitable for tweeting as one can hear and look at a handheld device at the same time, plus audience lighting is low but not black for say an orchestral concert which would make screen glow less remarkable.

Leslie Stainton: I think I felt a bit the way I did in third grade, passing notes back and forth during class and hoping I didn’t get caught, meanwhile missing most of what the teacher was trying to teach. I’m afraid the experience has not changed my (admittedly biased) opinion that tweeting–and much of social media, for that matter–is a largely superficial, narcissistic activity beloved by people with a tendency toward ADD. I didn’t mind tweeting during intermission, but when I did it during the performance I completely missed what was happening onstage and disrupted any sort of narrative continuity. I found myself thinking more about how clever I could be tweeting than about what the pieces were trying to say to me. It kept me from delving more fully into the experience. I was “present,” yes, but mostly to myself and the small gaggle of people who were tweeting and following tweets. In retrospect, I think I got the lesser end of the deal.

Do we really need to “perform” as we watch performances? And what about those audience members who were spending their time tracking tweets rather than engaging fully with what was happening onstage? And what about the poor performers–going through their extraordinary paces to a distracted audience?

Jordan Miller: I think that the tweeting greatly enhanced my experience. I was able to share my thoughts with a whole variety of people, and to hear what they had to say. There were some people tweeting with a much greater knowledge of dance than I have, and that helped me appreciate aspects I wouldn’t have even thought about.

UMS: Did you expect this effect or are you surprised by this outcome?

Paul Kitti: I really didn’t know what to expect, but I wouldn’t say I was surprised. The ongoing tweet conversation made it feel more like a community experience, which I thought was cool.

Mark Clague: One surprise to me was that our tweeting didn’t really amount to a conversation. I think this was because we were sitting together at the back of the hall and thus our dialogue happened by turning to each other in response to a tweet rather than using twitter. Several times one person would turn to another at an intermission break to say “nice tweet,” or to discuss a topic that might have been too sensitive to post to the world — for example, the sexual overtones of the opening dance. In this sense, tweets did create a conversation and introduced me to new people, but tweets served as conversation starters for a face-to-face dialogue rather than the conversation itself. I can imagine a twitter section doing something similar in that those who choose to sit there are making a statement that they are engaged in the performance to search for things to share and discuss. Therefore, one doesn’t feel awkward in turning to a neighbor during the show to find out their twitter ID name and to ask a face-to-face followup based on some observation. I’d love to experience a performance in which several dozens of tweeters were engaged as I wonder how the momentum of the electronic conversation might be different. I made new friends at the Santa Fe performance via Tweeting and what surprises me is that I’d recognize them today if they sat next to me on a campus bus. Rather than substituting for person-to-person engagement with virtual friends, my twitter seat experience created real world connections.

Leslie Stainton: I’m not convinced the activity of tweeting enriched my experience of the concert in any way. I’ll try it again Thursday (though can’t promise how actively I’ll tweet during a show, in French, that has no intermission!). It certainly doesn’t seem to be the same sort of reflective activity as, say, blogging, or writing up a comment for the Lobby. Maybe I’ll change my mind? Doubt it!

Jordan Miller: I hadn’t expected the conversation to be so robust. Not only were the official “tweeters” engaging, but there were other audience members tweeting during intermission and before and after the performance as well, and that was very cool. In fact, I was able to meet up with a student who was at the show and talked to her afterward.

Stay tuned for the next tweet seats event: Théâtre de la Ville’s Ionesco’s Rhinocéros on Thursday, October 11.

Presenting: UMS Tweet Seats Pilot Project

TWEET SEATS EVENTS

Tweet Seats 1: Aspen Santa Fe Ballet. Find out what happened.

Tweet Seats 2: Théâtre de la Ville: Ionesco’s Rhinocéros. Find out what happened.

Tweet Seats 3: Mariinsky Orchestra of St. Petersburg. Find out what happened.

Tweet Seats 4: Find out what happened.

WHAT ARE TWEET SEATS?

This season, UMS is launching a new pilot project: an experiment at the cross-section of live performing arts and technology commonly known as “tweet seats.”

Tweet seats refer to seats in which tweeting is permitted during the performance.

UMS has invited 5-7 people to participate in our tweet seats pilot project at 4 select performances. Only these 5-7 tweet seats participants will be permitted to use devices to participate in this pilot project; for the rest of the audience, our standard device policy applies (“Turn off all cellphones and electronic devices”).

The tweet seats participants will silence their phones and dim back-light to lowest setting; we’ve also prepared individual phone containers which will almost completely minimize any light emitted from the devices so that the experience of other patrons is not affected by tweet seats. Ensuring a smooth performance experience for all is our top priority.

At each of the 4 designated performances, participants are required to tweet 3-5 times using the hashtag #umslobby. No specific instructions for content of tweets are given. We’ll follow up with participants after the performance and chat with them about their experience; interviews will appear here on UMS Lobby.

You can follow or join the conversation after the performance here.

WHY TWEET SEATS?

Studies show that for some, engaging with technology is the preferred method of processing a performance and of “being present” at a performance.

In one such study, (“Making Sense of Audience Engagement”) Alan Brown & Rebecca Ratzkin refer to this subset of audiences as “technology-based processors.” They “love all forms of online engagement, and appear to be growing in number, especially among younger audience segments. Technology-based processors search for information online before and after the event. They connect with others on Facebook and other social media, and are most likely to read and contribute to blogs and discussion forums on the arts organization’s website. Their motivations are both intellectual and social in nature.”

So, we thought, let’s get together a group of people with differing attitudes towards technology to learn more about the effects of using technology during a live performance experience for all.

Our question: what can experimenting with technology teach us about being “engaged” or “present” at a performance?

OUR PARTICIPANTS:

We’ve pre-interviewed some of our participants so that you can get to know the range of attitudes that are part of the project. We asked them questions like:

- In one sentence, how would you describe your relationship with technology?

- What kinds of arts experiences do you like or look forward to most?

- To you, what does it mean to “be present” during a performance or another arts experience?

- What are you looking forward to in this experiment of experiencing performing arts with technology? What questions, concerns, reservations, or anxieties do you have about this experiment?

Learn more about them & their thoughts about technology and this pilot project below :

- Leslie Stainton, U-M School of Public Health Findings magazine editor and umslobby.org contributor

- Michael Kondziolka, UMS Director of Programming

- Mariah Cherem, Production Librarian at Ann Arbor District Library

- Paul Kitti, writer for iSPY magazine

- Mark Clague, U-M Associate Professor of Musicology and UMS Board member

- Greg Baise, Detroit-based concert promoter, arts writer, and DJ

- Garrett Schumann, composer, U-M Master of Music in Composition student, and umslobby.org contributor

- Neutral Zone and the University of Michigan participants

INTERVIEWS

UMS : Tell us about you. If you have an online presence you like to share publicly please tell us the relevant websites or user names/handles.

Leslie Stainton: I’m an editor at the UM School of Public Health and the author of a biography of Spanish playwright and poet Federico Garcia Lorca and a history/memoir of an American theater. My website is lesliestainton.com.

Greg Baise: I am Detroit-based concert promoter, arts writer, and occasional DJ. Some of my playlists can be found at vivaradio.com/lavie

Paul Kitti: I am a writer for iSPY Magazine, a monthly entertainment publication. I’ve spent the past two years covering a wide range of local events, including concerts, festivals, and screenings. Music and writing consume most of my brainpower, and I’ve found Ann Arbor to be an ideal environment for discovering new artists. In addition to journalism, I’ve held positions within U of M’s Athletic Department and Career Center. Magazine: http://mispymag.com/ LinkedIn: http://www.linkedin.com/profile/view?id=91711849&trk=tab_pro

Mark Clague: I’m an Associate Professor of Musicology, American Culture, African American Studies, and Non-Profit Management (whew!) at the University of Michigan School of Music, Theatre & Dance as well as a member of the UMS board. I tweet as @usmusicscholar and have a couple of WordPress blogs, including one on the bicentennial of the U.S. National Anthem (osaycanyouhear).

Michael Kondziolka: My name is Michael Kondziolka and I am the Director of Programming at UMS. My online presence is limited to Facebook and a couple of blogs that I regularly comment on.

Mariah Cherem: My love of music started with singing as a toddler, and has followed me through years of violin, various bands, and the occasional DJ set. My interest in how communities articulate their values through policy led me to EMU’s Arts Management MA program. A few years later, curiosity about online communities and the interplay between on and off-line behavior led me to UM’s School of Information. I now count myself extraordinarily lucky to be bringing all of these interests together in my work as a Production Librarian at AADL.

Garrett Schumann: I am a composer pursuing my doctorate in Music Composition at the University. In addition to writing music, I host a music show on Washington Public Radio called We Are Not Beethoven where the ever-changing place music holds in the 21st-Century world is discussed. Learn more at garrettschumann.com and follow me on twitter @garrt.

UMS: In one sentence, how would you describe your relationship with technology? OK, you can elaborate beyond this first “thesis” sentence if you would like.

Greg Baise: If a new record comes on vinyl with a digital download, I always opt for the vinyl over the cd. If the vinyl doesn’t come with a digital download, I buy the vinyl anyways.

Leslie Stainton: Troubled! I’m dependent on it, like everyone, and annoyed by it. I want it to do what I need it to do, and that’s it—I’m not a gadget person, don’t like games, don’t find technology interesting for its own sake. While I see the utility of social media, it strikes me as a giant time suck, and so I seldom engage—though I do enjoy blogging for UMS. I enjoy the way it makes me think more deeply about what I’ve seen onstage. I’ve done some tweeting and Facebook posting for the School of Public Health, but not enough to feel confident or particularly comfortable in either area.

Mariah Cherem: Technology can be fun and fascinating and super-mind-blowingly-cool, but I’m most interested in how people use it to connect to each other, to information/resources that they need, and to things that they’re passionate about. Also, I think our definitions of what constitutes “technology” are constantly shifting. A pen or a typewriter doesn’t seem like technology now, but there was once a point when it did.

Michael Kondziolka: I have an enigmatic relationship with technology. I tend to be a late adopter….and, while I accept that technology is here to stay, I sometimes bemoan its impact on our culture. In my view, the irony of “connectivity” embedded in much of mythology/ideology of social media is one of the great farces of our time: users seem decidedly less connected. (This is in no way an insightful observation as much has been written on the topic.) This fundamental concern aside, I can be a fanatical user of technology from time to time and I don’t think I could give up my iPhone at this point. I have social media sites that I use on a semi-regular basis. At the end of the day, I have a very healthy skepticism and think it is important to push back on assumptions in all sectors of life.

Garrett Schumann: I believe the Internet Web-based media have created a new and unprecedented aesthetic experience in the 21st Century, and it is imperative for those involved in the performing arts and other parts of culture to interact with and embrace those technologies if their work is to remain relevant to society at large.

Paul Kitti: I’m an email addict, avid texter and internet junkie with a loyalty to Apple products. Despite growing fully accustomed to the constant technological buzz of my generation, I still prefer hard copies of books and magazines.

Mark Clague: I enjoy exploring technology for new views on our world and to grow my own creativity, skills, and perspectives.

UMS: This pilot includes a broad range of performing arts experiences: theater, dance, global music, orchestral performance. What sorts of performing arts experiences are you most familiar with? More broadly, what kinds of arts experiences do you like or look forward to most? What do you wish to have more experience with?

Leslie Stainton: I did my BA in drama and my MFA in dramaturgy, so I’m passionate about live theater and know a fair amount about it, or at least once did. I’ve studied dance off and on and am interested in the form, though don’t know as much about it as I probably should. Ditto music: I’m married to a musicologist, and we attend many concerts and talk about music and listen to it at home. But I’ve never taken a theory course so don’t understand it in the kind of depth I’d like. I’m far more drawn to classical music than to popular forms, jazz, country, or so-called global music. I adore museums—think of them as spiritual centers and seek them out almost every time I travel—and spent six years working for UMMA. I’m interested in arts experiences that provoke and challenge, that cross traditional genres and boundaries, that make me think more profoundly.

Mariah Cherem: I am most interested in (and luckily can attend) the orchestral performance and the performance by Gilberto Gil. In general, at some point I’d love to do UMS “Night School” related to a dance performance, as that’s an area I feel that might help my enjoyment even more.

Greg Baise: In music, I’m mostly familiar with rock, world music, contemporary classical music and modern dance. I’m very interested in art history in general, and modern art in particular, especially stuff that’s too current for the latest art history surveys. I’d love to get deeper into experimental theater and more modern dance.

Paul Kitti: I’ve played a couple instruments and attended several classical concerts. The most memorable performance I’ve witnessed was “Einstein on the Beach” as presented by UMS earlier this year. My knowledge about theatre and dance is limited, although I’ve grown more and more interested in these types of productions over the past year. The art-related experiences I look forward to most are the ones involving music and/or acting.

Garrett Schumann: Because I am a composer I am most familiar with music and musical performances. However, I love all kinds of performing arts and cultural experiences from dance shows to theatrical performances and, particularly, contemporary arts exhibits.

Michael Kondziolka: Relatively speaking, I have a lot of experience with most forms of the performing arts and a passing familiarity with the others. I am least familiar with some forms of contemporary popular music and culture. I look forward to a broad range of experiences from the very traditional to the very experimental.

Mark Clague: My primary arts experience is as an orchestral musicians (bassoonist), but I also masquerade as a photographer, saxophonist, and singer. Inspired by John Cage, I like to challenge myself to explore new kinds of art and to open myself up to new ideas and experiences. Thus I’ve increasingly attended UMS dance, theater, and world music events to stretch beyond my orchestra and jazz comfort zone.

UMS: Why did you decide to participate in this project?

Michael Kondziolka: As a way of testing my own, sometimes staunch, assumptions.

Greg Baise: UMS’s programming plays a huge part in my cultural activities. HUGE. I’m still astounded that within the past year I’ve seen the Gate Theatre, Einstein on the Beach, and Jessye Norman perform John Cage, all thanks to UMS. I hope I can contribute through these tweet seats and raise awareness of UMS’s presence and programming. And I’m honored to be asked to participate.

Mariah Cherem: In general, I think very highly of UMS’s programming. I’m not often able to attend that many performances, however, due to time and budget constraints. I’ve been interested in how various technologies can help or hinder enjoyment or engagement in experiences (in this case, it’d be performances). I’m not sure that I think that Tweeting about performances is really quite right for me, but I’m willing to give it a shot and try it in the name of experimentation. This idea pushes me a little bit out of my comfort zone of “things I tweet about” or talk about online, and I think that nudging around one’s boundaries now and then is important.

Garrett Schumann: I use twitter a lot in my life both for fun and for professional purposes, so I feel like I am experienced enough with the technology to contribute a meaningful opinion to this project’s discussion. Also, I think the tweet-seat question is emblematic of performing arts organizations’ struggle to maintain relevance in the 21st-century.

Paul Kitti: I appreciate what UMS brings to Ann Arbor, and I’ve immensely enjoyed my past experiences with their productions. Honestly, the opportunity to witness and participate in these events is something I knew I couldn’t pass up.

Mark Clague: I’ve heard a lot of buzz about Tweet Seats and enjoyed the few times I’ve surreptitiously tweeted at an arts event and thus wanted to try it out for myself when it was “legal.”

Leslie Stainton: Because I’m addicted to working with UMS?!

UMS: To you, what does it mean to “be present” during a performance or another arts experience?

Garrett Schumann: Obviously, attending an event is step one to ‘being present’, but I think the phrase involves incorporating the experience you’ve had at a concert/performance into your life at large. By this, I mean talking to people you know about what you’ve seen/heard, breaking down your experience in conversations and sharing it with others either online or in person.

Greg Baise: Hmm. Present? Paying attention. Learning. Enjoying. Not distracted. Taking it in in the present, and remembering it for later, too.

Paul Kitti: Art requires the beholder to suspend all preconceptions and unrelated thoughts; to be present during an arts experience is to lend your mind as best as you are able to what is before you, constantly trying to identify the message, meaning, uniqueness or beauty of what you’re seeing and hearing.

Leslie Stainton: To shut out the workaday world and become utterly absorbed in the experience at hand; to come away with some new understanding.

Mariah Cherem: The ideas of presence and focus are those that I struggle with most when thinking about how this experience might go. For me, I often don’t want to be the lens – don’t want to be capturing pieces of something, as then I become detached. Even at rock shows, I get a little annoyed when the guy in the front feels the need to film everything instead of just getting into it and being “in the moment.” However, at the same time, I think that there may be potential for people to raise awareness of their experience of a particular musician, play, etc. via social media channels. I don’t want the arts to get lost in our larger conversations because we “shouldn’t” be talking about them in some way or another – using some tech or another.

Mark Clague: It’s more than just physically attending; To be present is to connect with the art and engage with it, allowing the motivations, messages, and even the spiritual dimension of the art to converse with you. For me Twitter is one way to honor that conversation by translating my nebulous experience into 140-character thoughts, documenting and sharing these, and potentially chatting with others about these reactions.

Michael Kondziolka: This, for me, is the nub of the issue. I do not tend to believe that a mediating device can truly help in this regard. Of course, there are tools that can help mediate the experience and enhance it — infra-red listening devices, subtitles, etc. But, at the end of the day, those are mediating tools which are necessary to aid the user in accessing some aspect of the presentation that they otherwise could not. Critique, the intellectual processing and analysis of what has happened, starts during the performance but is codified through words after the performance. (“How can I put this experience into words….?”) Even a non-critique, a purely emotion-based exclamation – “I loved that!” — to be tweeted, takes one out of the experience. I have yet to understand what/why/how the dimension of time plays into all this. I can’t wrap my head around why something tweeted in real time — at the moment it is felt or realized during a performance — is more valuable than something tweeted during a natural break in a performance — at intermission or after the show. (“Wow…impressive return to the tonic key!”) That is how we have always tended to process our collective experiences pre-technology…and I don’t understand why we frame the real-time possibilities offered by tweeting to be somehow better…or an improvement. (It may be, as umsLobby’s Musiclover would call it, a “disimprovement.”) I view the communication that takes place between a performer and an audience member — whether it be lyric, declaimed or movement based – to be sacred. Therefore, anything that breaks that bond is anathema to the notion of being “being present.” I also subscribe to basic norms, rightly or wrongly, of what I was taught to believe are civil manners — if someone is speaking (or performing) they deserve your full attention.

When I really drill down on this topic, I realize that I actually believe that the use of technology in new and possibly intrusive ways — in this instance, as part of the performance experience — is most probably an ideological metaphor of independence: a classic moment of generational division.. (“Look Ma, we have our own ways of doing things.”) And that ideological position probably exists outside the forum that is being created to address this question.

UMS: What are you looking forward to in this experiment of merging performing arts with technology? What anxieties, concerns, reservations, or questions do you have about this experiment?

Paul Kitti: I’m looking forward to simply experiencing these productions, and the chance to offer input and be engaged through technology is kind of an added bonus.

Greg Baise: I’m looking forward to new cultural experiences, and sharing my impressions and observations. And also getting feedback – I hope I say stuff that’s of interest to both my friends and to total strangers. I might be a little reserved about thinking about (or over-thinking) what I tweet, maybe to a point where I’m concentrating more on the tweet than the performance. Also, I’m concerned about interfering with the enjoyment of others through use of technology and wonder how isolated we will be from the general audience.

Michael Kondziolka: I am looking forward to the basic act of testing one’s strongly held views. I am most concerned about breaking the scared bond and I take solace in the fact that I can go again and have the same experience in a completely unmediated, truly present, way on a subsequent evening. Anxiety would come in the form of worrying that, through my actions, I am interfering in someone else’s sacred moment.

Leslie Stainton: I’m honestly not sure about my ability to tweet—haven’t quite gotten the hang of 140 characters and don’t really understand hashtags. I’m also frankly worried about the ADD element of all this—trying to multitask while watching a performance. I’m not at all sure I’ll enjoy the experience or want to repeat it, but I’m sufficiently curious I’m willing to try it once.

Mariah Cherem: I think that my answers to the two questions above actually already hit on these points! : )

Garrett Schumann: I’m most interested in the arguments against allowing twitter into the concert hall. Because I am unabashedly in favor of the ‘tweet seat’ idea, my bias tends to inhibit my ability to relate to the dissent that is out there, and I look forward to an opportunity to learn more about viewpoints that oppose mine.

Mark Clague: I’m looking forward to the real-time conversation with other Tweet-seaters; my only worry is in getting criticism from other patrons who either think we’re doing something wrong or who just personally object to social media in an arts event.

Stay tuned for more interviews with our participants about their experiences over the course of the pilot project.

People are Talking: UMS Night School – Session 4

UMS Night School is a free and open to the public series of “classes”, which include a 30-minute discussion of each performance in Pure Michigan Renegade, plus a 60-minute intro session for the next performance on the series. You’ll find follow-up conversation, coverage, and materials here on the Lobby.

See someone with this button? Start a conversation about ‘renegade’ works.

See someone with this button? Start a conversation about ‘renegade’ works.

SYLLABUS

HOMEWORK

“Required Reading” and “Required Watching” from Malcolm Tulip, Associate Professor of Theatre at U-M

1. The Turnip Princess: a newly-discovered fairy tale

“Once upon a time, the historian Franz Xaver von Schönwerth collected fairytales in Bavaria, which were locked away in an archive until now.”

2. Interview with Robert Lepage for Theatre Music Canada.

In Lypsinch (2007) Lepage intends to “show us a mosaic of human struggles for identity, to assemble a composite portrait of contemporary society voicing over and dubbing out our primal emotional needs. Lepage wants to make us aware of how we control and doctor the sounds surrounding us to cover up the voices of those in genuine need.” via Village Voice

3. Director Robert Lepage Speaks on what inspired him to create The Nightingale & Other Short Fables, a collection of works by composer Igor Stravinsky that made its world premier in October 2009.

4. More about The Andersen Project

A slideshow of images from the production

Preview in Paris Voice: “the piece is not a retelling of any one of Anderson’s tales but rather an open-ended study, undertaken to examine, create around and perhaps finally understand better both the creator and his work.”

5. More about Hans Christian Andersen

The Hans Christian Andersen Center (with complete works)

The Dryad

The Shadow

Elsewhere on the Lobby:

Our interview with The Andersen Project’s lead actor Yves Jacques, and 5 Things to Know About The Andersen Project.

YOU SUGGESTED…

We’ll add your suggestions for further reading, listening, and watching here.

What did you think of this session of Night School? What’s still not making sense? What are you excited about?

UMS Night School Report – Einstein on the Beach

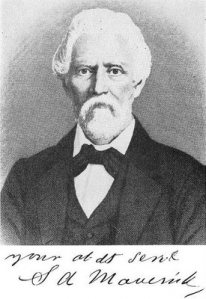

On the topic of “maverick,” one of the words being used to describe the artists on offer in the Renegade series, I learned at yesterday’s first UMS “Night School” session that its primary meaning is an “unbranded calf or yearling.” The term comes from one Samuel Augustus Maverick (1803-1870), an American rancher who refused to brand his own calves so that he could claim any unbranded calf he found as his own. Needless to say, he wasn’t a popular guy in his neighborhood. More broadly, the word “maverick” refers to something—a calf, for instance, or maybe a composer—that lacks any markings of ownership. I suppose that’s what John McCain had in mind in four years ago, but I’m glad UMS is reclaiming the word for us in something like its original context, and I’m intrigued to think of artists like Robert Wilson and Olivier Messiaen (whose From the Canyons to the Stars is next up in the Renegade series) as stubborn ranchers who flat-out won’t, or can’t, brand their work.

Lots of talk at last night’s class—attended by more than 70 people—about what to expect at next week’s Einstein on the Beach. Instructor Mark Clague went over what EoB is (an opera with poetic texts, recitative, an orchestra pit, and a mythic hero) and is not (Aida). Of particular note are the work’s five-hour length and non-narrative structure, and the attendant challenges for audience members. If I leave to go to the bathroom, how will I know what I’ve missed? people wanted to know. Just how repetitive is it? I caught up with Dennis Carter, head usher for UMS, who came to last night’s class to prepare himself for next week’s event.

Inspired? What do you think it means to be a “renegade”?

Why Renegade? with Time-Warping Powers

Photo: Philip Glass and Robert Wilson.

Photo: Philip Glass and Robert Wilson.

There was much to mull over at last Monday night’s roundtable discussion of the Renegade series. Panelists talked of the series as a 10-week, 10-performance “journey,” an “adventure.” They described it as a conceptual frame “for exploring how artists create innovative work.” (If the series does nothing else, I hope it gives us a new vocabulary for talking about “innovation,” that tired phrase.) Danny Herwitz of the UM Institute for the Humanities made a compelling case for a uniquely American brand of “renegade,” invoking figures as disparate as Whitman and Aaron Copland, Emerson and Clint Eastwood, John Cage and John Wayne. “In America a renegade is someone who refuses the templates of convention,” Herwitz said, and issued something of a challenge when he suggested the series might allow us to imagine the country’s future at a time when many of us have lost faith in that future. “To remember the voices of these composers”—Cage, Copland, Philip Glass—“is to remember something about the experiment in which we were born.”

But more than anything I came away from the discussion thinking about time. Maybe it’s because I’m into my fifties and ever more keenly aware I’m on the short end of the lifespan stick. I think of the old woman in Emily Mann’s play Annulla who says, “Everything has gone by so fast.” Maybe it’s the world we inhabit, this cacophany of blogs and tweets and video clips, information coming at you so fast you can barely skate the surface. Increasingly I find myself wanting silence and space, the ability to make a connection that doesn’t involve an electronic gadget.

In his marvelous book Einstein’s Dreams, the novelist and physicist Alan Lightman writes of the ways that time bends experience—a phenomenon we came to understand with particular clarity in the last century, thanks in large part to Einstein himself. Lightman describes how time moves “in fits and starts,” how it “struggles forward” when one is rushing a sick child to the hospital and “darts across the field of vision” when one is eating a good meal with close friends “or lying in the arms of a secret lover.”

It is this sense of time as somehow malleable—and also manipulable—that marks many of the works in the Renegade series, most obviously, perhaps, Einstein on the Beach, which UMS’s Michael Kondziolka described on Monday as a “durational experience. If you give yourself over to it, you feel as if you’ve walked through the looking glass.”

Time, said Danny Herwitz, “is fundamental to a lot of these Renegade artists. They at once speed everything up and slow it down. They’re trying to put you in a different frame of reference.” And more provocatively: “There is a way in which [these artists] rescue one from the frame of modern life.”

May it be so.

Having decried technology, I’ll now use it, with apologies, to let you hear another panelist, musicologist Mark Clague of the UM School of Music, Theatre, and Dance, share his thoughts on time and the Renegade series.

ONCE. MORE.: an introduction by Mark Clague

Next week UMS, the U-M School of Music, Theatre & Dance, and the U-M Institute for the Humanities present ONCE. MORE. marking the 50th anniversary of the legendary avant-garde ONCE festivals. UMS has a complete listing of events and a comprehensive festival guide posted at www.ums.org/once. To frame the week, we offer you this amazing essay from U-M professor Mark Clague:

The Creativity of Community: Ann Arbor, the University of Michigan, and the ONCE Phenomenon, 1961–68

by Mark Clague, PhD, associate professor of musicology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

“Once” signals intensity, a singularity of purpose. Never a thing, once is always in action: a fleeting opportunity to be seized in time and witnessed. Once is energy, excitement, ambition, possibility, community. Every art, in its broadest sense, aspires to once. Performance catalyzes intent to transform time into communication: while materials may be reused—performer, audience, and context are always in motion, always changing, and thus artistic expression occurs in precisely the same way only once. Yet art is often frittered away as timeless rather than timely. Static, hung on a wall or embalmed in history, its process unappreciated, it fails to communicate even once. When composers Robert Ashley, George Cacioppo, Gordon Mumma, Roger Reynolds, Donald Scavarda, and their colleagues announced ONCE—they trumpeted the raw ambition to create sounds that were original, certainly, but that also engaged, sparked debate, and echoed into the future. Thus, some five decades later, their creativity is heard “ONCE. MORE.”—not as nostalgia but as ongoing exploration. The periods in the name signal once again their interest in expression over continuity.

Roger Reynolds, Donald Scavarda, George Cacioppo (Ann Arbor, 1963). Photo: Bernard Folta, courtesy of Donald Scavarda

The first ONCE Festival of avant-garde performance comprised four concerts on successive weekends—February 24–25 and March 3–4, 1961—in Ann Arbor’s Unitarian Church (now the Vitosha Guest Haus at 1917 Washtenaw). Concerts alternated between guest artists typically from Europe or New York and recitals by the host composers. The opening concert featured members of Pierre Boulez’s “Domaine musical” ensemble from Paris with composer Luciano Berio and multi-vocalist Cathy Berberian. Pianist Paul Jacobs presented music by Schoenberg, Webern, Krenek, Messiaen, Boulez, and Stockhausen on the third concert, while concerts two and four included chamber works by Ashley, Cacioppo, Mumma, Reynolds, and Scavarda, along with then-graduate students Sherman Van Solkema and Bruce Wise. Ashley also contributed an electronic accompaniment to George Manupelli’s film The Bottleman. The concerts sold to capacity and Ann Arbor’s Dramatic Arts Center (DAC), which sponsored the event, covered a deficit of only about $125 on a total budget of $1300 (ca. $9000 in 2010 dollars).

Even before the first festival closed, its success inspired talk of a second. All told, there would be six ONCE festivals over the course of five years (1961–65), while the ONCE Group, a theatrical troupe led by Robert and Mary Ashley, remained active through 1968. Critics moaned “Once is enough” and “Once too often,” yet the festivals grew. The fourth was the largest at eight performances, while the last, held on the roof of Ann Arbor’s Thompson Street parking garage (and thus providing for the sale of more tickets), even returned a small profit to the DAC. Programs for a total of 29 festival events list some 170 works by 92 composers. Guest artists included John Cage, Eric Dolphy, Morton Feldman, Lukas Foss, Alvin Lucier, Pauline Oliveros, David Tudor, LaMonte Young, and others. By any measure, ONCE was monumental. Reviews appeared in the local press, as well as in the Musical Quarterly, Boston Globe, Toronto Star, and Preuves (Paris). Dozens of guest appearances took ONCE artists to Detroit, New York, San Diego, Los Angeles, Paris, Rome, Tokyo, and beyond, to perform under rubrics including ONCE Friends, ONCE a Month, ONCE Removed, ONCE-Off, and ONCE Echoes. Related initiatives by ONCE artists, especially Ashley and Mumma, such as the Collaborative Studio for Electronic Music, the Truck Ensemble, New Music for Pianos, and the Sonic Arts Group (later Union), carried Ann Arbor’s experimental music, film, and theater far and wide, only increasing the impact and reputation of ONCE. Similar festivals arose in Seattle, Toronto, and Tucson, while in 1963 the Ann Arbor Film Festival arose from its cinematic efforts. ONCE artists even recreated Milton Cohen’s Space Theatre at the 1964 Venice Biennale, and the festival propelled several participants to careers outside of Ann Arbor: Reynolds to the CROSS TALK presentations in Tokyo and then to UC San Diego, Mumma to the Merce Cunningham Dance Company in New York (and later to UC Santa Cruz), and Ashley to Mills College in Oakland.

ONCE Group at Robert Rauschenberg’s loft after Judson Dance Theater Festival (New York, 1965). (Front, L–R): Joseph Wehrer, Robert Ashley, unknown, George Manupelli; (second row, L–R): Yvonne Rainer, George Kleis (leaning against palm), unknown, Gordon Mumma, unknown, Cynthia Liddell; (third row, L–R): Jackie Leuzinger, Annina Nosei, unknown; (seated in back on the right holding sandwich) Caroline Blunt; others unknown. Photo: Makepeace Tsao, courtesy of the Tsao Family

The primary driving force of ONCE, however, was not fame (and certainly not fortune), but the deep desire of its composers to hear their music. Many ONCE composers were also fine musicians; their passion for new music and dedication to excellence in its performance was clearly infectious, attracting dozens of volunteer instrumentalists and even administrative talents eager to share in their work. Yet the momentum of the festivals also inspired creativity: Scavarda notes, “Suddenly we could write anything we wanted and have it heard.”(1) Although deliberately cutting edge, ONCE was not doctrinaire. Performances embraced a wide range of materials (found sound, text, film, multiphonics, non-metrical time), methods (serialism, graphic notation, indeterminacy, improvisation, electronic synthesis, tape manipulation, audience involvement, theater), and aesthetics (modernism, expressionism, collage, happenings). ONCE composers shared a common goal, but never a single artistic manifesto. For Mumma the festival was radical; for Scavarda it was simply pragmatic.

Progressive politics saturated the University’s social milieu in the 1960s. Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) held its first meeting in Ann Arbor in 1960 and on October 14 of that same year President John F. Kennedy proposed the Peace Corps from the steps of the Michigan Union. Yet many ONCE compositions were focused explorations of musical materials and procedures; they assert a right to individual creative radicalism without additional reference to contemporary events. Politics motivates the art of ONCE directly only in certain instances (e.g., Reynolds’ A Portrait of Vanzetti) but often appears obliquely (e.g., Ashley’s in memoriam…). As Ashley remembers, “Everybody was into those ideas by default because they were all around you. But the ONCE Group, by some tacit agreement, we never did anything political; it seemed in bad taste because you’d be preaching to the congregation.”(2) Nevertheless, political overtones can be heard frequently in the music of ONCE, possibly because such issues were so much a part of the era’s socio-cultural discourse.

The spark that ignited ONCE is often attributed to a car ride back to Ann Arbor from Stratford, Ontario, where Ashley, Cacioppo, Mumma, and Reynolds had attended the International Conference of Composers (August 7–14, 1960). Intended to foster exchange among the world’s leading modern composers, the symposium welcomed participants from 20 countries. These musical pioneers included Berio (Italy), Henri Dutilleux (France), Josef Tal (Israel), and Elizabeth Maconchy (England), as well as Ernst Krenek, Otto Luening, George Rochberg, Vladimir Ussachevsky, and the 75-year-old Edgard Varèse—all then living in the US. While symposium concerts were open to the public, papers and discussions were not, and thus Ann Arbor’s contingent left frustrated after having managed to speak with only a handful of their famous colleagues. They concluded that they could do a better job on their own.