How to produce Einstein on the Beach

Photo: Section of a drop in Einstein on the Beach.

Photo: Section of a drop in Einstein on the Beach.

Mel Brooks’s “Producers” they’re not. “No way we’ll become become rich on this,” Linda Brumbach said yesterday at UM’s B-School in a 90-minute public conversation about the ins and outs of producing Einstein on the Beach. Brumbach is the head of Pomegranate Arts, the tiny production company that’s taken on the near-impossible task of bringing Einstein to the stage here in A2 and in 10 other venues around the world. The tour ends in Hong Kong in March 2013, and Brumbach says she’ll consider it an artistic success if “Bob, Phil, and Lucinda get the piece they want.” That’s Robert Wilson, Philip Glass, and Lucinda Childs, the artists who gave birth to the monumental opera in 1976 and have seen only two revivals since then.

After yesterday’s session, I understand why. The 1976 premiere of Einstein cost $750,000, and Wilson had to put huge chunks of that sum on his American Express card and then plead with Amex to waive interest charges. Glass had to sell the score to offset costs.

This week’s production costs a staggering $2.5 million—and that doesn’t include touring expenses. UMS President Ken Fischer said that for UMS to make money on this, “we’d have to charge $500 a ticket, and we’re not about to do that.” “I don’t think anyone can actually make money on Einstein on the Beach,” Brumbach added.

Why the exorbitant price? Consider:

• The model for Einstein’s sets costs as much as $90,000

• It takes three freight containers to ship the production

• Props include 600 pounds of dry ice

• Costumes include 30 pairs of converse high-tops

• Tech rehearsals require three solid weeks at the Power Center (the other day, Wilson spent 14 hours lighting just one scene)

• Load-in at each new venue takes three days

• Contracts for touring venues contain a 26-page technical rider

• European venues are operating in euros

• 35 press agents are needed to promote the opera worldwide

• In A2, the production requires 65 company members and 35 local stagehands

For Brumbach, the dream of producing Einstein is 12 years in the making. She first set out to revive the opera in the early 2000s, but 9/11 and its aftermath halted those plans. In 2007, it looked as though New York City Opera would partner with Pomegranate to stage the work, but the opera company’s budget was slashed and the season cancelled. A promised Paris production went nowhere. It wasn’t until UMS’s Michael Kondziolka said to Brumbach a year or two ago, “We’ll do it,” that she saw a way.

UMS is one of seven co-commissioners—three in the U.S., one in Canada, the rest overseas, and all of them “friends,” says Brumbach—who’ve gone in with Pomegranate to make this week’s historic preview performances (and subsequent tour) happen.

They’re still teching inside the Power Center as I write. One last drop is being repainted in Detroit and will be delivered to the theater at 2 pm Friday. There’s more than an element of brinksmanship to all of this. I wouldn’t want to be in Brumbach’s shoes just now, but I’m quite eager to witness her dream-come-true this weekend.

Not Quite-Live-Blogging Robert Wilson and Philip Glass Conversation at the Michigan Theatre

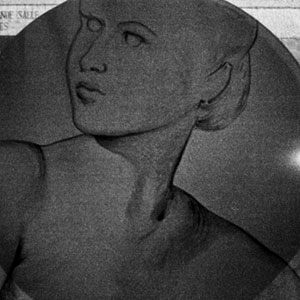

Editor’s Note: Last night’s Penny W. Stamps Speaker Series featured a conversation with Einstein on the Beach co-creators Philip Glass and Robert Wilson. Anne Bogart, acclaimed theater director, moderated the conversation. Leslie Stainton blogs about the event below.

Photo: Philip Glass and Robert Wilson.

3:45 pm*

I have to ask someone to move over a seat so that there’s room for my two friends and me. The place is jammed, top to bottom. Balcony, orchestra. There’s a sound guy behind me, and a videographer up front, and dozens of people are milling about in the aisles. You’d think the Golden Globes were taking place.

*Times are approximate

4:15 pm

After a round of introductions, director Anne Bogart, who’ll moderate the conversation, takes the podium. She tells us A2 is the place to be this coming week, because we’ll get a window into the “extraordinary trajectory of this production.” She reminds us that since its inception in 1976 and its last iteration in 1992, “our lives have become faster and faster.” Einstein, she notes, “changes the time signature”—a suggestion I find beguiling.

4:20 pm

We see documentary video footage of Glass and Wilson, with snippets of the original 1976 production. Either Glass or Wilson—I can’t remember which—describes Einstein as “the god of our time.” I wonder if that holds for the 21st century?

4:30 pm

Wilson and Glass take the stage to rapturous applause. Bogart mentions the ovation. “We haven’t done anything yet,” Glass mumbles. Laughter. Surely I’m not the only one thinking, “Oh, but you have.”

4:35 pm

Wilson describes the early stages of Einstein’s development. He and Glass shared a “common sense of time and space,” he remembers. They agreed on a common megastructure and a total time length. Each man followed the same structure but filled it in different ways. This is a theme Wilson will repeat throughout today’s conversation: Form—whether of something as big as an opera or as minute as an actor’s gesture—is less important than how it is filled. Appearances to the contrary, the form of Einstein is “very classical, very formal,” Wilson says, and something we should all recognize—theme and variation.

4:40 pm

Glass observes that every time they’ve produced Einstein—in 1976, 1984, and 1992—they’ve drawn huge numbers of young audience members. Judging from the crowd in the Michigan, it’s still true.

4:50 pm

There’s talk of how radical it was in 1976 to produce an abstract work like this in a conventional setting like the Metropolitan Opera House—at a time when lofts and street theater were the rage. (Wilson remembers thinking, “What’s wrong with illusion?”) He and Glass had to rent the Met for a day in order to put on Einstein that day. “We didn’t actually have the money,” Glass interjects. Because of the opera’s five-hour duration, without intermission, the Met bars made a killing. I’m reminded that the Power Center can’t sell booze, which seems a pity.

5:00 pm

Wilson urges audiences to come and go during Einstein the way they would in a park. “It’s always going on, something is always happening.” This way, there’s “not so much difference between art and living. If you want to sit for five hours, that’s OK. If you leave in the second act and come back in the fourth, you’re not lost. It’s not like Shakespeare.” Much laughter.

Glass adds, “The audience completes the work. The piece by itself doesn’t work.”

5:10 pm

On process, both Wilson and Glass caution against knowing too much when you embark on a project. Glass: “If I know what I’m doing, then I don’t have anything to do.” Wilson: “As I got older, I learned that if I pre-decide, I often waste time, instead of going in with no idea. Let the beast talk to you instead of you talking to it.” Both say the starting point of a piece doesn’t matter. The process itself becomes the content.

5:15 pm

Glass gets a laugh when he recalls how John Cage once chided him: “Philip, too many notes.”

5:20 pm

Performer and choreographer Lucinda Childs joins the conversation. Bogart speaks of how riveting Childs’s performance in Einstein was when Bogart first saw it in 1976 and again in, I think, 1992. Bogart’s referring to the moment when Childs spends 20 mintues crossing the stage back and forth on a diagonal. For years Bogart wondered why she couldn’t take her eyes off Childs, what Childs had to teach her about the arts of acting and directing. The answer—proposed here by Wilson—seems to be that as an actress, Childs filled every single moment. He talks of the “sheer stamina” the production demands of actors, which is matched, he adds, by the stamina of watching it.

5:25 pm

Wilson unlocks something for me when he speaks of the difficulty some critics have with Einstein because it’s abstract. We can accept works by Jackson Pollock as abstract, Wilson explains, but not something we call “opera” or “theater.” Nor do conservatories or theater schools tend to include the term “abstraction” in their curricular vocabularies. Wilson says abstraction is liberating for him. This seems critical to understanding what we’re about to see onstage this week.

5:30 pm

Questions from the audience. Long lines form in both aisles. The first questioner wants to know why the opera has such short runs whenever it’s produced. Money, Glass answers. Wilson claims the same production will cost 3-4 times more to mount in New York City than in Paris. A stagehand at Carnegie Hall, he adds, makes more money than Obama.

Someone asks for advice for young artists. “Keep working,” Wilson urges. He’s not being facetious.

A stage-design student wants to know how to meld set, costume, and lighting design. Wilson notes that in conventional opera staging, sets often distract from sound, and vice versa. The question designers and directors should ask, he believes, is “How can what I am seeing make me hear better? Can I create something onstage that makes me hear the music better than I do when my eyes are closed?”

5:40 pm

In response to a long-winded and confusing question about novels and language, Wilson is more than generous. He speaks of his work with autistic children, of the difficulties that ensue when actors inject their own emotions and feelings into texts rather than letting the texts speak and audiences decipher their meaning for themselves. He says it’s “OK to get lost” when you’re reading a complicated novel or listening to a Shakespeare sonnet (or, we can infer, watching something like Einstein). “TV has changed our way of thinking. Do you understand? Do you get it?” TV is forever asking that, forever explaining. Wilson: “It’s OK to get lost.”

5:42 pm

The visual space in Einstein is organized in three very traditional ways, we learn. Portraits, still lifes, and landscapes. Bogart mentions the influence, as well, of vaudeville, and Wilson agrees, noting that Chaplin and Keaton are both inspirations.

5:45 pm

The session ends with an exchange that must warm the hearts of many in the crowd. An audience member asks why Wilson and Glass chose to reconstruct the show here in A2. Glass cites the financial practicalities of mounting a huge production like this in a noncommercial theater and mentions the educational benefits for both audience and cast, crew, and Glass and Wilson themselves.

But Wilson delivers the money quote. Ann Arbor, he says quietly, “is one of the cultural strongholds of this country.”

With that, Bogart ends the discussion and sends us out into the cold. The sun has set, the sky is a pale lavender, and the street lights are glittering. The place feels even brighter than it did two hours ago, in full daylight.

[VIDEO] Einstein on the Beach – Original Creative Team

This winter UMS is presenting a 10-week, 10-event ‘renegade’ series focusing on thought-leaders and game-changers in the performing arts.

The opera Einstein on the Beach opens the series. Widely credited as one of the greatest artistic achievements of the 20th century, Einstein launched director Robert Wilson and composer Philip Glass to international success when it was first produced in Avignon, France in 1976.

In this video, featuring the original creative team, Philip Glass remembers the first night of Einstein, Robert Wilson sits next to Arthur Miller, and Lucinda Childs recollects the “Supermarket Speech.”

Part of Pure Michigan Renegade.

The 2012 production of Einstein on the Beach was commissioned by: University Musical Society of the University of Michigan; BAM; the Barbican, London; Cal Performances University of California, Berkeley; Luminato, Toronto Festival of Arts and Creativity; De Nederlandse Opera/The Amsterdam Music Theatre; Opéra et Orchestre National de Montpellier Languedoc-Rousillon. Produced by Pomegranate Arts, Inc.

11/12 International Theater Series

This year’s International Theater Series features three productions at the Power Center. The series begins with Ireland’s acclaimed Gate Theater Company performing a double-bill of two one-act plays by Samuel Beckett, Endgame and Watt. As previously announced, the series continues with Einstein on the Beach, the seminal opera by Philip Glass and Robert Wilson with choreography by Lucinda Childs. Considered one of the most remarkable performance works of our time, this performances launches a world tour of what will likely be the last reconstructions of this work designed and led by its original creators. Closing the series is The Andersen Project, a solo performance created by Canadian theater visionary Robert Lepage and performed by Yves Jacques that explores sexual identity, unfulfilled fantasies, and the thirst for recognition and fame through Hans Christian Andersen’s timeless fables.

Subscription packages go on sale to the general public on Monday, May 9, and will be available through Friday, September 17. Current subscribers will receive renewal packets in early May and may renew their series upon receipt of the packet. Tickets to individual events will go on sale to the general public on Monday, August 22 (via www.ums.org) and Wednesday, August 24 (in person and by phone). Not sure if you’re on our mailing list? Click here to update your mailing address to be sure you’ll receive a brochure.

Samuel Beckett’s Endgame and Watt

Gate Theatre of Dublin

Michael Cogan, director

Thursday, October 27, 7:30 pm

Friday, October 28, 8 pm

Saturday, October 29, 8 pm

Power Center

Straight from Ireland comes the Gate Theatre, largely considered the interpreter of Beckett in the world. Endgame, like Waiting for Godot, is considered one of Beckett’s most important works, written in a style associated with the Theatre of the Absurd. The bizarre adventures of Watt (a novel written while Beckett was in hiding during World War II) and his struggles to make sense of the world around him is told with elegant simplicity, immense pathos, and explosive humor. This week-long residency will be accompanied by a week-long festival of the complete Beckett works on film.

Philip Glass & Robert Wilson’s Einstein on the Beach

Lucinda Childs, choreographer

Friday, January 20, 7pm

Saturday, January 21, 7pm

Sunday, January 22, 2pm

Power Center

“The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious.” — Albert Einstein

Widely credited as one of the greatest artistic achievements of the 20th century, this rarely-performed work will be reconstructed for a major international tour (including the first North American presentations ever held outside of New York City) nearly four decades after it was first performed and 20 years since its last production. Non-narrative in form, the work uses a series of powerful recurrent images as its main storytelling device, shown in juxtaposition with abstract dance sequences created by American choreographer Lucinda Childs. Prior to the production’s final technical rehearsals and world premiere in Montpelier, France, UMS will host the creators, musicians, performers, and crew for Einstein for three weeks as they reconstruct and rehearse the work for what is likely to be the final world tour designed and led by its creators. These early preview performances will be the only opportunity to see Einstein on the Beach in the Midwest.

Click the video below to watch some excerpts from Einstein on the Beach with audio commentary from collaborator Robert Wilson.

The Andersen Project

Ex Machina

Robert Lepage, artistic director

Thursday, March 15, 7:30 pm

Friday, March 16, 8 pm

Saturday, March 17, 8 pm

Power Center

Filled to the brim with his trademark humor and visual and technological brilliance, this off-the-wall masterpiece by Canadian theater visionary Robert Lepage stars Yves Jacques (Far Side of the Moon) in a one-man tour-de-force about a Canadian writer from the rock-and-roll milieu who is unexpectedly commissioned by the Opera Garnier in Paris to write a libretto for a children’s opera. Freely inspired by the timeless fables written by Hans Christian Andersen, who as it turns out, didn’t really like children, as well as anecdotes from the author’s personal diaries, The Andersen Project keenly explores unraveling relationships, personal demons, the thirst for recognition, and compromise that comes too late.

Return to the complete chronological list.