UMS Playlist: Social Change and African Popular Music

This post is a part of a series of playlists curated by UMS staff, artists, and community. Check out more music here.

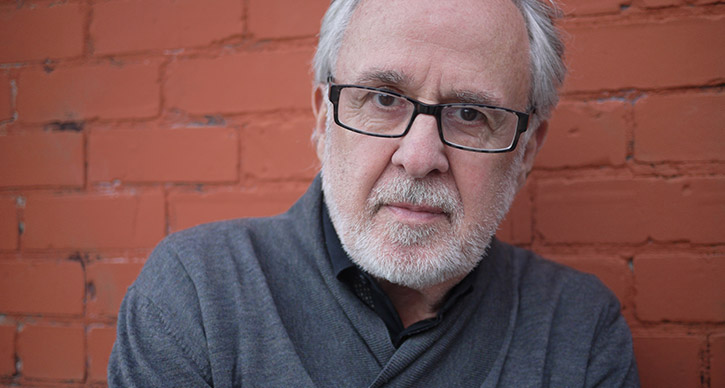

Oliver Mtukudzi. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Zimbabwe’s Afropop legend Oliver Mtukudzi performs in Ann Arbor on April 17, 2015.

“Tuku” has created 61 solo albums to date, many of which focus on political and social themes. His band The Black Spirits got its start performing songs protesting the white colonial rule of Zimbabwe in the 1960s and 70s.

Throughout his career, Tuku has refrained from direct political criticism, instead using metaphor to communicate his ideas: “The beauty of the Shona language is that it is endowed with all those rich idioms and metaphor…and the beauty of art is that you can use the power of language to craft particular meaning without necessarily giving it away. So, I used the beauty of Shona to communicate in my own way and people got the message.”

Themes of social change are common in popular African music. In this listening guide, explore some of the history of this connection.

1. Nelson Mandela commissioned the group “Sipho Hotstix Mabuse” to write a campaign theme song for his bid to be South Africa’s first democratically elected president in 1994. Simply titled “Nelson Mandela,” the song speaks frankly about the Mandela’s hopes to promote unity in the country.

2. Angelique Kidjo (who last performed in Ann Arbor in 2013) blends musical traditions from her native Benin with Western popular music, singing in English as well as her childhood languages of Fon and Yoruba. Many of her songs include themes of peace, tolerance, and liberation. In “Kulumbu,” Kidjo speaks about the nececsity for women to participate in conflict resolution after suffering disproportionately during war.

3. The title of Bassekou Kouyate’s song “Jama Ko” translates to “the gathering,” and urges for peace and reconciliation in Mali. Bassekou Kouyate last performed in Ann Arbor as part of our 2013-2014 season.

4. Tuku’s song “Wasakara” describes the corruption and violence of the government of Zimbabwean president Robert Mugabe. He sings, “Admit it, you are wrinkled/You are worn out.”

5. Thomas Mampfuno also criticizes the government in “Mamvemve,” with the lyrics “the country you used to cry for is now in tatters.” Zimbabwe’s political environment is so restrictive that Mampfuno has not visited the country since 2004.

6. In “Ndakuvara,” Mugabe is represented by an ox too stubborn to learn from its elders. Through metaphor, Tuku writes protest as subtext subtle enough to allow him to remain in Zimbabwe.

What did you think about this playlist? What songs would you add?

UMS Playlist: Evolution of Chamber Music

This post is a part of a series of playlists curated by UMS staff, artists, and community. Check out more music here.

eigth blackbird. Photo by Luke Ratray.

The Chicago-based chamber ensemble eighth blackbird performs in Ann Arbor on January 17. eighth blackbird is on the new frontier of contemporary music. As Los Angeles Times explains, “the blackbirds are examples of a new breed of super-musicians. They perform the bulk of their new music from memory. They have no need for a conductor, no matter how complex the rhythms or balances… [They are] stage animals, often in motion, enacting their scores as they play them.”

How did chamber music, which originated in the Middle Ages, evolve into the music of the blackbirds? Explore the history with our listening guide:

1. Chamber music originated during the Middle Ages as a form of entertainment for guests in palace chambers. “Mille Regretz” by Josquin des Prez (1450-1521) is an example of the style and structure of sacred music translated to a secular song that describes the pain of a lost love. The earliest chamber music often also included lutes, recorders, and early versions of the violin, viola, and cello.

2. The string quartet, one of the most common chamber ensembles, developed into its current form in the early 17th century. Since then, composers from Haydn to Beethoven to Shostakovich have revered the string quartet’s form because of the challenge of writing four unique parts that constantly change and interact with one another. The string quartet includes two violins, viola, and cello. In this track, listen for Beethoven’s mastery of “counterpoint,” the relationships between the voices.

3. Chamber music in the 20th century brought together new instrument groupings. The brass (featuring two trumpets, trombone, French horn, trombone, and tuba) rose in popularity in the 1940s. Victor Ewald is widely considered to the first composer of brass quintet music.

4. Chamber music concepts extend across genre; though “chamber music” is primarily used to describe classical music, the John Coltrane Quartet exemplifies excellent chamber music playing.

5. eighth blackbird illustrates the vast range of 21st century chamber ensembles. On this track, the group performs Steve Reich’s minimalist composition “Fast: 8:39.”

6. eighth blackbird showcases its virtuosic ensemble connectivity with Thomas Adés’ rhythmically complex “Catch.”

7. eighth blackbird collaborates with electronic music composer Dennis Desantis on the track “strange imaginary remix.”

What did you think about this playlist? Share your thoughts or song suggestions in the comments below.

Listening Guide in Samples: Bob James

Jazz keyboardist and composer Bob James is also one of the most sampled musicians in the history of hip-hop. He’ll perform in Ann Arbor on November 15, 2014. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Hip-hop appropriated the soul and rhythms of many genres of music and cultures, and hip-hop is contagious. It’s a force that blasted its way out of the inner city into bedrooms and basements everywhere.

Hip-hop is rooted in making something out of nothing, using the few tools at the musicians’ disposal to create art that paints a picture of a part of society largely ignored. Before hip-hop’s inception, jazz, blues, soul music, and rock-n-roll were the prior generations’ outlets for creating a rich counter-culture that would influence the communities of the future. Hip-hop was an explosive melting pot of all of these cultures, and so it wasn’t shocking that many of musicians who had begun to experience success in earlier decades enjoyed a new life through sampling in hip-hop. One such example is jazz pianist Bob James.

From One by Bob James:

In the 70s, James was arranging and producing with many fellow jazz artists, including on saxophonist Grover Washington Jr.’s classic albums, while also putting out his own solo albums like One or Two. These albums and his other music would become the foundation of many hip-hop staples of the 80s and 90s. The worlds Bob James would create during this time, while working with musicians such as saxophonist Dave Sanborn, singer Hubert Laws, and drummer Idris Muhammad, to name a few, were filled with a massive soul that mixed dreams of fantastical lands with the struggles of reality. The culture of hip-hop would reinvent that feeling in the following generations.

“Angela” by Bob James:

Bob James, who is an alumnus University of Michigan, would go on to success in the jazz world, but his music really entered American living rooms everywhere when he penned “Angela,” the theme music for the popular TV show Taxi that aired from 1978 to 1983 and spawned a slew of well-known actors and comedians. Later on, “Angela” would be sampled by Bay Area hip-hop group Souls Of Mischief for their song “Cab Fare”, which was slated for their 1995 full length album No Man’s Land but was unfortunately axed because they could not get the sample legally cleared (it’s out there now, go look for it!).

The works of Bob James have been sampled many times within hip-hop as well as by R&B and drum-n-bass artists, but there are two specific songs that have been used more than anything else and have lead to some well-known hip-hop records.

“Nautilus” by Bob James, sampled:

From the Bob James’ 1974 album One, the closing track titled “Nautilus” has given us great hip-hop songs over the years. As we enter the first few seconds of “Nautilus,” we hear the haunting sounds would be sampled by the legendary producer DJ Premier for Jeru The Damaja’s “My Mind Spray” from his 1994 album The Sun Rises In The East. Then, a few seconds later, right as the song really kicks in, is the sample that the Wu Tang Clan’s The RZA used for fellow group-mate Ghostface Killah’s “Daytona 500” from his 1996 solo album Ironman. “Nautilus” has been sampled in dozens of other songs including by Eric B. & Rakim (“Let the Rhythm Hit ‘Em”) and Soul II Soul (“Jazzie’s Groove”), but it’s the segment about two-thirds into the composition, during another ghostly breakdown, that Run D.M.C. would pick up and turn into the main infectious sample for their renowned record “Beats to the Rhyme.”

“Take Me to the Mardi Gras” by Bob James, sampled:

While the sampling of “Nautilus” spawned many hip-hop tracks, James’s 1975 album Two and the song “Take Me to the Mardi Gras” resulted in some of the most legendary tracks. The bells and drum breaks from “Mardi Gras” would be most famously sampled by hip-hop legends like Run D.M.C. (“Peter Piper”), LL Cool J (“Rock The Bells”), and the Beastie Boys (“Hold It Now, Hit It”). “Take Me to the Mardi Gras” isn’t just the foundation for these celebrated songs, it’s also the backdrop for the sound of late 80s hip-hop culture. Those bells and drums from “Mardi Gras” create the vision of inner city kids break-dancing on the sidewalks, spitting rhymes on the corner, or tagging graffiti on a wall downtown.

Bob James has continued to produce and arrange music as a highly successful solo jazz artist and along with his legendary band Four Play, but his work from the 1970s as a producer, arranger, and as solo artist has left a lasting effect on in the hip-hop world, an effect that will continue for generations of emcees and producers to come.

Interested in learning more? Check out Kelly Frazier’s listening guide to pianist Ahmad Jahmal, who’s also been sampled into the hearts of hip-hop.

Wild Forces at Play

Photo: Colin Stetson, who performs in Ann Arbor on April, 18, 2018. Photo by Scott Irvine.

It begins with a deep breath, followed by resonant palpitations underlying the emergence of whistles, screeches, honks, and warbles that are progressively arranged and hoisted into a creature of dazzling, dizzying complexity. At each moment in this evolution of sound—highlighted by its spiraling melody and blistering ostinati—collapse feels imminent, and chaos, inevitable.

This specimen, “And It Thought to Escape,” exemplifies the unpredictable long-form sonic structures created by the saxophonist Colin Stetson. “And It Thought to Escape” clocks in at over eight minutes, and yet this song seems to fly by, as do others by Stetson, whose gradual and fitful development of melody is surprising and mesmerizing.

“And It Thought to Escape”

A sweat-flecked, lung-wringing feat

Avant-garde, jazz, and indie music scenes are frothing over with innovative and talented musicians whose songs explore dissonance, repetition, and non-traditional forms, especially through the use of digital effects and loops. What distinguishes Stetson from the masses is his virtuoso technique on saxophone—including alto, tenor, baritone, and the formidable bass—clarinet, and French horn.

He’s a master of circular breathing—the method of using stored air in the cheeks to continue playing while inhaling through the nose, in order to produce a seamless sound—which allows him to perform and record his long solos live and in a single take, without overdubbing or loops. Stetson has honed his circular breathing for twenty years; he learned it at age fifteen, from a music instructor who told Stetson that the technique would help him interpret classical string music without having to pause and take breaths.

While the method is somewhat tricky to learn, its use isn’t rare among wind instrumentalists. Stetson’s use of circular breathing is remarkable, though, given the extreme intensity and duration of his songs, such as the leviathan “To See More Light,” a fifteen minute song from his latest solo album, New History Warfare, Volume 3: To See More Light. The song opens with disconnected blares of the saxophone and passes through tonal states of frenzy, delirium, and grim weariness, before arriving at a warm and vaulted unity.

There’s a raw physicality to Stetson’s music. It howls. It heaves and churns. Watch Stetson perform live and a song becomes more than a song but a sweat-flecked, lung-wringing feat of musicianship requiring tremendous stamina. In many songs we hear his breathing: it’s a faint breeze in “To See More Light,” and a steady gust filling the interstices between lightning-fast synth-sounding trills in “Nobu Take” on New History Warfare, Volume 1. “This all originates in breath. It’s all tied to breath, it’s all tied to my body,” said Stetson about his music in a 2011 interview with Jian Ghomeshi, host of the CBC talk program Q. Stetson discussed his reason for avoiding digital gadgetry, explaining that his music, from the moment of its composition, is inexplicably bound with the physical process of its creation. “The parameters that I had set up for myself, initially, [were] just that everything that could be captured in the moment, physically, by me with the instrument, was fair game, but no additions, no effects, no electronics or anything like that.”

“Nobu Take”

From digital to otherworldly

It’s clear that Stetson’s parameters have been more liberating than limiting. He has undertaken a serious exploration into the sonic-making capabilities of the saxophone. Not only is he adept at creating densely layered music, but he does so with a variety of sounds, rhythms, and textures not commonly found in solo saxophone music. The music is deeply human, but its sound can range from digital to otherworldly. In “Tiger Tiger Crane” on New History of Warfare, Volume 1, Stetson uses the saxophone keys to tap out a ghostly hip-hop rhythm. There are trenchant, wordless vocals that frequently surface out of fuzz and static on the albums New History Warfare, Volume 2: Judges and To See More Light.

While recording the songs for Judges, Stetson used up to twenty-four microphones—in the studio and attached to his sax and himself, including a dog-collar microphone over his vocal chords—in order to capture the full spectrum of sounds he was producing. The song “Judges” is an excellent example of Stetson’s polyphonic abilities: he lays down an irresistible rhythm and bass line and then adds a lacerating wail as fierce as rock music’s most scorched-earth vocals. In the first video below, Stetson performs “Awake on Foreign Shores” and “Judges.” In the second video, he dissects the different sounds that comprise “Judges.”

On “A Takeaway Show”

Colin Stetson breaks down “Judges”

Stetson is an Ann Arbor native who studied at the University of Michigan. Older jazz lovers might remember him as a member of the popular avant-garde jazz-funk group Transmission, which performed around Ann Arbor and Detroit during the latter half of the ‘90s. Younger music fans are sure to recognize the groups and artists he’s performed, recorded, or toured with, including the Arcade Fire, Bon Iver, TV on the Radio, Tom Waits, David Byrne, The National, Laurie Anderson, Antibalas, Lou Reed, among many others. All music enthusiasts are sure to find something to enjoy in his solo work, which he began focusing on in 2003 while living in New York City.

In 2008, Stetson released his debut solo album, New History Warfare, Volume 1, followed by 2011’s Judges and 2013’s To See More Light. Each album in this conceptual trilogy is unique; when considered as a whole, they reveal an emotional, physical, and mental deepening of Stetson’s craft. Each album balances long, epic songs with short pieces that span just a minute or two in length and which serve as heightened meditations on a discrete phrase or rhythm. There is some over-dubbing of guest vocals: Laurie Anderson supplies ominous spoken word pieces to Judges, and Bon Iver’s Justin Vernon lends his distinctive, soaring voice to songs on To See More Light, including “Who The Waves Are Roaring For.”

“Who The Waves Are Roaring For”

I’ve resisted labeling Stetson’s music as one genre or the other, because it’s something that Stetson refuses to do. And for good reason: his musical aesthetic, while at one time rooted in free jazz, is so healthy and permeable that it has allowed many different styles and genres to enrich it, without being stunted or saturated by one in particular. There’s jazz, pop, hip-hop, metal, post-rock, drone, minimalism, folk, electronic, and more. Whether your record collection contains Evan Parker or Sonic Youth, it’s easy to find something to enjoy in Stetson’s impressive and groundbreaking body of solo saxophone works. To return to Jian Ghomeshi’s interview with Stetson, Ghomeshi at one point asked Stetson to comment on the fact that his music doesn’t resemble most saxophone music, that Stetson was “creating music that isn’t even identifiable as sax.”

“It will be identifiable as sax,” Stetson responded. “Everything that I use is stuff that has really been utilized for decades in the free jazz and free improvisation traditions. I’m just re-contextualizing. I’m telling my own story with it.”

In Studio Q:

[LISTENING GUIDE] Introduction to Sarod

Ustad Amjad Ali Khan performs on February 16 in Ann Arbor’s Hill Auditorium.

The sarod is an Indian stringed instrument used mainly in North Indian (Hindustani) classical music. The sarod’s ancestry links to the Afghan rabab, which is a wooden Central Asian lute that is covered with skin. Similar to the sitar, its more well-known stringed instrument cousin, the sarod is a smaller stringed instrument that is held in the musician’s lap. The conventional sarod is a lute-like instrument with 17 to 25 strings. Of these, four to five strings are used to play the melody, while one to two are drone strings, two are chikari strings, and nine to ten are sympathetic strings.

The sarod is an Indian stringed instrument used mainly in North Indian (Hindustani) classical music. The sarod’s ancestry links to the Afghan rabab, which is a wooden Central Asian lute that is covered with skin. Similar to the sitar, its more well-known stringed instrument cousin, the sarod is a smaller stringed instrument that is held in the musician’s lap. The conventional sarod is a lute-like instrument with 17 to 25 strings. Of these, four to five strings are used to play the melody, while one to two are drone strings, two are chikari strings, and nine to ten are sympathetic strings.

Claimed as “one of 20th century’s greatest masters of the Sarod” by Songlines World Music Magazine in 2003, Ustad Amjad Ali Khan is a sixth-generation sarod player in his family, which originated the esteemed Gwalior-Bangash gharana (a gharana is a system of social organization linking musicians or dancers by lineage or apprenticeship). It is said that Ustad Amjad Ali Khan’s ancestors had developed and shaped the instrument over several hundred years. Ustad Amjad Ali Khan was six years old when he gave his first recital on the sarod.

Ustad Amjad Ali Kahn on Improvisation in Indian Music & the Sarod

Listening guide

This year’s UMS listening guide serves as an introduction to the sarod and contains mainly Hindustani classical music featuring the instrument. You can also find more information on Ustad Amjad Ali Khan and sarod music on sarod.com

Raga Mian Ki Malhar with solo by Ustad Amjad Ali Khan

Ustad Amjad Ali Khan performs at Philharmonie Köln

Aman Ali And Ayaan Ali Khan perform at Modern School

Ayaan Ali Khan performs

Ustad Amjad Ali Khan performs Raag Maru Bihag

Interested in learning more about classical Indian music? Explore Meeta’s guide to improvisation in classical Indian music.

[LISTENING GUIDE] Improvised Classical Indian Music – Zakir Hussain & Masters of Percussion

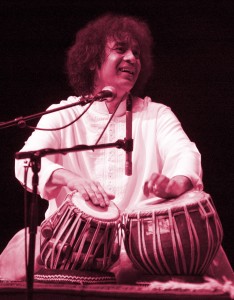

Editor’s Note: UMS is presenting Zakir Hussain & Masters of Percussion on Thursday April 12th. Zakir Hussain is the pre-eminent classical tabla virtuoso of our time. Masters of Percussion, an outgrowth of Hussain’s memorable tours with his father, the legendary Ustad Allarakha, has enjoyed successful tours in the West since 1996.

While there is a set program for this concert, no two performances of Indian classical music are ever the same. Zakir Hussain explains, “The thing about Indian art is that it’s based in improvisation. You take an idea and then you expand it in a spontaneous manner. It’s difficult to tie it down to ‘Okay, so many things will happen’, because you never know what idea will emerge, and what that would lead to, and where it will go. But the fact is that the musicians who are on stage are the best in their genre. They are considered great masters where they come from. So one thing that is for sure is that the music will be of very high quality.”

While there is a set program for this concert, no two performances of Indian classical music are ever the same. Zakir Hussain explains, “The thing about Indian art is that it’s based in improvisation. You take an idea and then you expand it in a spontaneous manner. It’s difficult to tie it down to ‘Okay, so many things will happen’, because you never know what idea will emerge, and what that would lead to, and where it will go. But the fact is that the musicians who are on stage are the best in their genre. They are considered great masters where they come from. So one thing that is for sure is that the music will be of very high quality.”

The following listening guide, curated by Meeta Banjerlee, provides an overview of Indian classical music and is a good representation of the style of music that will be played at the upcoming performance.

Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia: Deepchandi (Bansuri):

Ustad Zakir Hussain: The Great Indian Desert (Tabla)

Pandit Ravi Shankar & Philip Glass: Passages (Sitar and Orchestra)

http://youtu.be/ugIbmTKrcHc

Pandit Ravi Shankar: Rag Rasia (Sitar)

Ustad Shahid Parvez: Dhun Bhairavi (Sitar)

http://youtu.be/8t5Gm1ewRQA

Pandit Nikhil Banerjee: Raga Malkauns (Sitar)

http://youtu.be/Ldfk_2yk7AA

Pandit Ram Narayan: Raag Jogiya (Sarangi)

Pandit Ram Narayan: Raag Darbari (Sarangi)

Ustad Amjad Ali Khan: Raga Bahar (Sarod)

Ustad Rashid Khan: Thumri (Vocal)

— Meeta Banerjee began learning the sitar at the Detroit Institute for Indian Music in 1989. She has performed all over Michigan in venues such as the Detroit Institute of Arts, Ann Arbor Book Festival, and the North American Bengali Conference. In 2005, she was invited as a featured artist for the Michigan Pops Orchestra’s “Pops Around the World.” She is a member of the local Indian fusion music group Sumkali and is a University of Michigan alum.