Interview: Theater maker Young Jean Lee

Moments in Untitled Feminist show (left) and Straight White Men (right). Photos by Julieta Cervantes and Brian Mediana.

“Young Jean Lee is, hands down, the most adventurous downtown playwright of her generation.” (New York Times) This January, UMS showcases Young Jean Lee’s two most recent theater works on gender and identity. The plays are performed across the street from each other in the Power Center and Lydia Mendelssohn Theatre.

UMS Lobby regular contributor Leslie Stainton interviewed Young Jean Lee ahead of the visit.

Leslie Stainton: How do you define “theater”?

Young Jean Lee: I don’t have a definition for it. If someone calls it “theater,” then to me it’s theater.

To my knowledge, this will be the first time anyone’s deliberately paired Untitled Feminist Show with Straight White Men. What do you hope happens from that juxtaposition? What are you most curious about?

The shows are so different and appeal to such different audiences, but for me they’re both coming from a similar place. My hope is that seeing them back to back will encourage audiences to look for their similarities.

How do you go about choosing a language—verbal, nonverbal—for a specific work about a particular topic?

I’m always trying to find the best match between form and content. For the first workshop of Untitled Feminist Show in 2010 I wrote a script and after the showing, our audience did nothing but make academic arguments about feminism. I wanted to hit people on a more emotional, visceral level, so as we did more workshops, I kept cutting out more and more of the text until there was nothing left but movement, and the audience was forced to react emotionally. I tried hard to write words that could compete with the movement and dance, but I couldn’t. We found that movement communicated what we wanted much more strongly than words did

For Straight White Men, I saw the traditional three-act structure as the “straight white male” of theatrical forms, or the form that has historically been used to present straight white male narratives as universal. And I thought it would be interesting to explore the boundaries of that form at the same time as its content.

What role do you see for live performance in our technological age? In what ways, if any, must live performance evolve and/or adapt in a world of rapid technological change?

Theater has been around forever—it’s survived the advent of radio and television and film. It’s become part of our educational system. I don’t really see it going anywhere.

What issues are you yearning to tackle in your work (or not, given your penchant for writing about “the last thing” you’d want to write about!)?

The Native American genocide has been on my mind a lot lately.

What are you working on now?

I’m trying to figure out how to make my first feature film!

When did you first fall for live performance?

There was a summer stock theater in the town where I grew up, and my parents took me to see A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum when I was very young, and I was hooked.

Many of your pieces deal with identity. In what ways is theater especially well suited for addressing questions of identity?

I don’t know that it is. Identity is hard to address in any art form, I think.

What key trends do you see in American theater today?

I think that contemporary American theater is very aesthetically conservative, and that it charges way too much for tickets. It isn’t adventurous or challenging enough — I’m thinking of mainstream commercial theater where everything has a linear plot line and there’s very little formal experimentation. I think the New York experimental theater/performance scene is still exciting. The stronger artists tend to have longer developmental processes. The performers have a lot of charisma and intelligence. There’s a lot of collaboration. On the other hand, I think a danger with experimental theater is when it gets locked into its own kind of tradition and you just see a bunch of experimental-theater cliches being played out.

See Young Jean Lee’s Straight White Men and Untitled Feminist Show in Ann Arbor January 21-23, 2016.

Greek to Us: Q&A

With a work like Antigone—especially with a new translation, by the remarkable and always provocative Anne Carson—it’s tempting to focus on text. But as T.S. Eliot reminds us, ancient Greek drama is first and most importantly action:

Behind the dialogue of Greek drama we are always conscious of a concrete visual actuality, and behind that of a specific emotional actuality. Behind the drama of words is the drama of action, the timbre of voice and voice, the uplifted hand or tense muscle, and the particular emotion. The spoken play, the words which we read, are symbols, a shorthand, and often, as in the best of Shakespeare, a very abbreviated shorthand indeed, for the actual and felt play, which is always the real thing. The phrase, beautiful as it may be, stands for a greater beauty still. This is merely a particular case of the amazing unity of Greek, the unity of concrete and abstract in philosophy, the unity of thought and feeling, action and speculation in life.

—T.S. Eliot, “Seneca in Elizabethan Translation”

Why new translation?

New translations of canonical texts get commissioned all the time—often as a way to spotlight a hot new playwright. It’s frequently the case that the playwright doesn’t even speak the original language, so a theater company will commission a “transliteration” from a native speaker and/or scholar. The American playwright Constance Congdon, who has adapted both Molière and Gorki into English, describes “transliterations” as “more of a dramaturgical booklet”—a line by line rendering of a text, heavily footnoted with contextual info on words, meanings, cultural assumptions, how other translators have handled certain passages, and so on.

With Anne Carson, of course, there’s no such intermediate stage. A classicist and poet who’s long tangled with Greek and Latin, Carson brings all that contextual knowledge to bear on each line she translates. To get a good sense of the kinds of issues she must consider, look at her 2010 Nox, a book-length meditation on her brother’s death, in which Carson intersperses personal reflection with lexicographical entries detailing the multiple meanings of each word in a Catullus elegy.

About Nox, Carson has said, “Over the years of working at it, I came to think of translating as a room, not exactly an unknown room, where one gropes for the light switch. […] Prowling the meanings of a word, prowling the history of a person, no use expecting a flood of light.”

It may be helpful to think of a translation of a play as like a production of that play, in that both are provisional interpretations. The original text endures.

Antigone, Antigonick

This is the second time in recent years that Carson has visited Antigone, the third tragedy in Sophokles’ great Oedipus trilogy. In 2012 Carson published Antigonick, an enigmatic reimagining of the story that in parts hews to Sophokles’ original script but also roams further—to Brecht and Beckett and John Ashbery; to contemporary law; to Hegel’s take on “woman” and Lacan’s and George Eliot’s take on the character of Antigone; to the 1944 Paris premiere of Jean Anouilh’s Antigone, before an audience of French Resistance leaders. Antigonick features a mute character named Nick who is onstage throughout and who “measures things.”

Carson speaks of the difficulties of translation in a four-page epistle (“the task of the translator of antigone”) with which she opens Antigonick. Addressing Antigone directly, Carson writes:

my problem is to get you and your problem

across into English from ancient Greek

all that lies hidden in these people, your people

crimes and horror and years together, a family, what we call a family

Of the Antigone we’ll see in Ann Arbor, Carson has said, “Translation cannot convey the complex interactions of [the play’s] metaphorical system or the inevitability of the catastrophe to which it leads.” In particular, she notes that the play’s two main characters, Antigone and Kreon, “stand opposed to one another instinctually, in the very morphology of their language, in the very grain of the way they think and speak.” Watch for how this plays out onstage.

And listen for Carson’s startling rendering of certain phrases—

you greedy pissant little amateur terrorist

…

run your scam

take your profit

you will not lay that body in the grave

…

but human beings are susceptible

aren’t they, dear old Teiresias

to the profit-motive

—reminders of how contemporary this play’s meanings are.

Some Particularities of Greek Theater: Q&A

An interview with actress Juliette Binoche, who stars in Antigone by Sophokles

How does the production handle the chorus?

The ancient Greek chorus was an anonymous group of 15 men who typically stayed onstage throughout a performance, in the orchestra (or round stage). Their chief function was to sing and dance the choral odes that divide the acts of the tragedy. They also, occasionally, sang or chanted in lyric dialogue with the actors, and their leader—distinguished by costume—could also take part in the dialogue.

Ivo van Hove, who directed the production of Antigone we’ll see in Ann Arbor, cautions: “If you are not interested in the chorus as a director, better take your hands off a Greek tragedy. Better not do it.” Of the chorus in Antigone, he says it is “almost like the subconscious of the society.”

How does the production handle the gods?

No actual god appears in Sophocles’ Antigone, but the uncanny and the divine are formidable powers in the play, keenly felt and heeded. Carson describes the difficulty of capturing the essence of the Greek term eusebia—the “awe that radiates from gods to humans and is given back as worship”—in this tragedy. She settles on the English word “piety,” but concedes its utter inadequacy in this instance. You’ll hear it in the last words Antigone speaks before going to her death:

I was caught in an act of perfect piety.

The actor who speaks these words, Carson writes, “will evoke the permanent elsewhere of our longing for the love of gods by drawing it up from her own voice and being.” How will Binoche render it?

What about exits and entrances?

In his long and thoughtful examination of ancient Greek theater, Greek Tragedy in Action (1978), Oliver Taplin notes that entrances and exits are not just a matter of “stepping into or out of the action,” but key events that draw attention to the relationships on either side of them. An entrance is a first chance to gauge a character’s features, dress, attributes. By its manner and destination, an exit conjures the future. Pay attention to both.

What objects and tokens does the production employ?

Greek tragedy is sparing when it comes to stage props. When they’re used, it’s to define and substantiate characters’ roles, status, way of life.

What happens offstage? And on? And why?

What we typically think of as the “big” actions—battles, disasters, suicides—take place offstage in Greek drama. Of greater interest is how individuals react to those events.

The slow pace and sustained concentration of Greek tragedy can also seem alien. Antigone is no Shakespearean romp from heath to court to jail to bedroom. The number of actors is limited (generally no more than two to three principal actors onstage at a given time). Time and place are unified. The chorus is ever-present. But this is not a static, verbal, didactic work—it’s deeply theatrical and emotional.

Mirror scenes

Greek tragedians often set up pairs of scenes—almost always so as to underscore the differences between those scenes. The spareness of Greek drama makes these pairings all the more powerful. Often these twin scenes occur on either side of a central catastrophic reversal or peripeteia (Aristotle’s term). Watch for such scenes between Kreon and Antigone; Kreon and those who bring him information (the Guard, Teiresias); Kreon and the chorus.

Why do you think theater makers “return to the Greeks”? Will you see Antigone by Sophokles?

The State of Theater in Ann Arbor: Looking Back to 2000, and Looking Ahead

Editor’s note: This article initially appeared in the Ann Arbor Observer in October 2000 and offers a snapshot of the history of theater in Ann Arbor and major developments in the city’s theater life during this time.

Leslie Stainton is a regular contributor to UMS Lobby, focusing on theater. Her new book Staging Ground captures the history of one of America’s oldest and most ghosted theaters—the Fulton Theatre in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

She participates in an authors panel on January 28, 2015, which also included U-M faculty Martin Walsh and Leigh Woods. While the panel will spotlight Staging Ground, it will also provide an updated look at the state of theater in Ann Arbor today.

We thought this “time capsule” would be a great read ahead of that panel.

Arthur Miller, Lee Bollinger, and the U-M’s dead-serious campaign to bring Ann Arbor back to the theatrical big leagues.

It’s been nearly sixty-five years since Arthur Miller sat in a rented room at 411 North State Street in Ann Arbor and in six days wrote his first play. That work, No Villain, won Miller a Hopwood Award worth $250—half the sum it had cost him to come to Michigan in the first place—and convinced him he had what it took to compete with the reigning Broadway playwrights of his day: people like Clifford Odets, Maxwell Anderson, and Philip Barry.

Today, of course, Miller’s name outshines all the rest. “He’s the greatest living American playwright,” says U-M English prof Enoch Brater. With Eugene O’Neill and Tennessee Williams, Miller created the plays that became the bedrock of American theater. His best-known work, Death of a Salesman, has been performed around the world. Last year’s Broadway revival won four Tony Awards half a century after the play premiered in 1949.

Arthur Miller returns to Ann Arbor this month to give the keynote address at an international symposium honoring him on his eighty-fifth birthday. It’s an auspicious moment in the American theater, nationally as well as locally.

An Up and Down Track Record in Ann Arbor

From New York to California, the commercial stage is thriving. For the first time in years, thanks to a booming economy, every theater on both Broadway and Off Broadway is lit. Big musicals earn huge grosses in New York and spawn profitable touring productions that play to packed houses in places like Toronto and Detroit. Nonprofit theater attendance across the country is also up, according to a 1999 survey by the New York–based Theater Communications Group, as are artist salaries, education and outreach programs, and individual giving. But the costs of producing theater are higher than ever, and competition for arts funding is fierce.

Ann Arbor—whose theatrical track record is at best “up and down,” says Russ Collins of the Michigan Theater—offers a portrait of the art in miniature. Home to one of the oldest university theater programs in the country, the city courted the Guthrie Theater in the late 1950s but lost out to Minneapolis. In the 1960s, under the auspices of the U-M’s Professional Theater Program (PTP), Ann Arbor played host to one of the foremost nonprofit repertory theaters in America, Ellis Rabb’s Association of Producing Artists, or APA. At its heyday in the mid-1960s, the APA earned praise from New York Times critic Walter Kerr as “the best repertory company we possess.” The Times called Ann Arbor “a major regional theater center.”

Since then, it’s been a roller-coaster ride. By 1970 the APA had largely dissolved. The PTP continued to bring in touring shows from the likes of Ontario’s Stratford Festival and John Houseman’s Acting Company, but its visionary co-directors, husband and wife Robert Schnitzer and Marcella Cisney, retired shortly after the construction of the Power Center for the Performing Arts in 1971. In 1973 the PTP was merged into the U-M theater department and placed under the direction of the department chair, a move that further weakened the once maverick organization. “It never got back on its feet again, which is heartbreaking,” says longtime producer, performer, and Ann Arbor theater patron Judy Dow Rumelhart.

Rumelhart herself was involved in a brief attempt to create an outdoor Greek theater festival in Ypsilanti in the late 1960s. The theater’s first and only season starred Ruby Dee, Dame Judith Anderson, and Bert Lahr. But fragile community support, poor leadership, and a deteriorating economic climate doomed the effort.

In the late 1970s Ann Arbor theater aficionado Jim Packard spearheaded an ambitious town-gown endeavor to organize a summer performing arts festival on the scale of Stratford. “I believe it is the manifest destiny of Ann Arbor to become the cultural capital of the region,” Packard said at the time.

But despite an elaborate, two-year planning process that included detailed marketing and feasibility studies, consultations with nonprofit theater professionals throughout the country, and grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, among others, the project foundered—partly because of turf wars between the city and the university, partly because of a statewide recession, and partly because the university was not prepared to market the endeavor on the scale it required. From the spoils of the project, today’s much smaller Ann Arbor Summer Festival emerged.

Twice in the 1980s the U-M tried to establish professional companies in alliance with its theater department, but both efforts—Walter Eysselinck’s Michigan Ensemble Theater and John Russell Brown’s Project Theater—folded after a few seasons. In each case, the department chair was simultaneously artistic director of the professional company, in an arrangement that had already proved unworkable in the early 1970s.

In 1991 Hollywood actor Jeff Daniels opened the Purple Rose Theater in his hometown, Chelsea. In 1996 Ann Arbor’s Performance Network went professional. Both companies are opening new theaters this season, a mark of their prosperity (see sidebar, “Reversals of Fortune”).

But Purple Rose and Performance Network are small companies that present exclusively new plays on modest budgets. Ann Arbor continues to lack the kind of first-rate anchor that a large-budget, nationally visible theater such as the Guthrie in Minneapolis provides.

In a now legendary irony, Sir Tyrone Guthrie toyed with putting his theater in Ann Arbor in the late 1950s but ultimately chose Minneapolis because of its more lucrative business climate. U-M administrators gave Guthrie an initially “cool reception,” remembers Wilfred Kaplan, who was involved in the effort to lure Guthrie to Ann Arbor. That, coupled with a lukewarm response from the Detroit business community, steered Guthrie away from Michigan. “Everyone had to come together, and they didn’t,” Kaplan recalls.

Theater: The Weak Sister

Today, Ann Arbor’s theater scene doesn’t begin to approach its musical and dance offerings in either quality or quantity. In a town that routinely sees the likes of the Berlin Philharmonic, Yo Yo Ma, Mark Morris, and the Martha Graham Company, theater is “the weak sister,” says Russ Collins. Collins attributes the situation to Ann Arbor’s German-immigrant heritage. “Music is strong because the Germans valued it. These social patterns hold sway even when the ethnic relevance has gone away.”

For U-M president Lee Bollinger, theater is the missing link in Ann Arbor’s otherwise rich cultural picture. “We should have theater that is as vibrant as the music that we experience on campus,” he says. A passionate advocate of the arts who carries a copy of Shakespeare with him much of the time and tries to read something from it “almost every day,” Bollinger has put theater at the center of his vision for the university. In fact, the former law professor and dean is the one person with both the imagination and the means to change not only the university’s but Ann Arbor’s theatrical fortunes in a big way, and he seems determined to do it.

At a press conference last spring, Bollinger announced plans to build a Walgreen Drama Center near the Power Center, on the university’s Central Campus. The new complex will include two theaters: a 600-seat Arthur Miller Theater and an as yet unnamed 100-seat space.

During the same press conference, University Musical Society president Ken Fischer announced the launch of the first full-fledged theater season in the organization’s 122-year history. The season, which opens this month, will include appearances by the Gate Theater of Dublin, Harvard University’s American Repertory Theater, and a three-week residency by one of the world’s foremost classical theater companies, the Royal Shakespeare Company. The season ends next April with a performance piece that UMS has co-commissioned with composer Benjamin Bagby and theater director and visual artist Ping Chong.

A Look at the RSC Residency

By far the largest, most expensive, and riskiest component of the UMS theater season is the RSC residency. “It’s the biggest thing we have ever done. Ever,” says Fischer. RSC is presenting all eight Shakespeare history plays in chronological order in a single year, an “extraordinary dramatic marathon,” in the words of the New York Times, that’s rarely been tried on any stage. The company will present four of those productions at the Power Center next March. In addition to paying the staggering cost of transporting a company of fifty-three (thirty actors and a crew of twenty-three) to Ann Arbor for three weeks, UMS is contributing significantly to the cost of producing the series, which will open in its entirety in Stratford, England, move to London, and conclude in abbreviated form in Ann Arbor. No other foreign tour is planned.

The transatlantic partnership that has evolved between the two groups is unique, according to Barbara Grove, RSC’s American representative: “It goes much beyond a tour. This has turned into a prototype.” Under the terms of its agreement, RSC will visit Ann Arbor at least two more times in the next five years and will make UMS its premier university partner in the United States.

The company itself “honestly contends they could not have done this cycle as they’re doing it without the University of Michigan,” Grove says. As a measure of its respect, RSC recently invited Bollinger to serve on its American board of directors.

Bollinger realizes that many in the community find his interest in theater surprising. “One of the great things about being university president,” he admits, “is that people have such low expectations of your cultural interests.”

If UMS is unable to raise its $2.5 million share of support for the RSC project, Bollinger has guaranteed that the university will make up the shortfall. In addition, he has already assembled most of the $20 million it will take to build the Walgreen Drama Center. Michigan alumnus Charles Walgreen Jr. has contributed between $11 and $12 million to the project, and Bollinger will use an undesignated bequest to the university to cover most of the rest.

Arthur Miller Theater

He is especially eager to build the Arthur Miller Theater. While some believe the university is moving too fast on the project—“I believe they should have [first] built an entire theater department, an Arthur Miller School of Theater,” says Rumelhart—Bollinger contends that it’s time the university honored its link to one of the most enduring voices in American, and indeed world, culture. “This is what you hold up to the students—that one of the greatest playwrights of the twentieth century found his talents here,” the president says.

When he first pitched the idea of an Arthur Miller Theater to Miller himself, the playwright sent back a note that now sits, framed, in Bollinger’s office. “The theater is a lovely idea. I’ve resisted similar proposals from others but it seems right from Ann Arbor,” Miller wrote.

The question now is whether Bollinger’s commitment portends a new golden age for theater in Ann Arbor—or whether this is just another bump in the roller coaster.

In Arthur Miller’s heyday, the great playwrights of the age were all seen on Broadway. Production costs and ticket prices for New York and major touring shows weren’t as prohibitive as they are now, and the theater was part and parcel of middle-class life and culture. Certain plays—Death of a Salesman among them—became part of the nation’s collective consciousness.

That happens far less frequently today—“which doesn’t mean the theater is in a bad state,” suggests Enoch Brater, who is organizing this month’s Arthur Miller symposium and will be a key participant in the Musical Society’s theater outreach programs. It does mean, though, that the old rules don’t apply. Theater—especially theater in a digitized, cable-ready twenty-first century—must reinvent itself, as it has countless times in its history, if it is to be anything but a quaintly anachronistic pastime.

Why do people go to the theater, anyhow?

Why do people go to the theater, anyhow? Simply to be entertained? To be sociable? To learn something? Or does live theatrical performance continue to meet some fundamental human need that no other medium can approach?

Obviously, those who have devoted themselves to the art think it does. Broughton believes “the more time we spend in front of these TV monitors, the more we want live entertainment. Theater lets you interact.”

“The more inundated people are with technology that’s been manipulated and studied to appeal to a preconceived notion of what audiences want, the more valuable live performance is,” maintains UMS’s [Director of Programming] Michael Kondziolka. “We program against that culture. And guess what? People are hungry for it. People are coming in record numbers to our programs, which are decidedly non–market driven—if by ‘market driven’ you mean tested and focus-grouped and surveyed and preresearched.”

At Chelsea’s Purple Rose, selling live theater to young audiences, in particular, is “a survival issue,” says artistic director Guy Sanville. “Tomorrow’s audiences are found in today’s classrooms.” What’s more, Sanville contends, theater is “a healing alternative to a chemical high. Arts and music are the drugs of choice for millions of kids.”

At its most basic level, a volunteer theater like the Ann Arbor Civic serves much the same social function as a church—it’s a gathering place for the community. Although he does not want the university’s multimillion-dollar Arthur Miller Theater to serve exclusively as a community theater, Lee Bollinger has said he is “open” to both community and student use of the space. He does not intend to place it under the control of either the theater department or the School of Music, however. Bollinger’s vision is larger than that. He’s convened a universitywide committee to consider plans for the new complex, as well as a trio of informal advisors: Broadway producer Robert Whitehead, Purple Rose founder Jeff Daniels, and Jack O’Brien, a Michigan alumnus who is artistic director of the Old Globe Theater in San Diego.

Bollinger concedes that he’s not yet sure what will go into either the Miller Theater or the Walgreen Drama Center once they’re built. He wants the complex to be a place for the creation of new work. He’ll seek an endowment to fund national and international collaborations with professional companies and a playwright-in-residence program. He’s toying with the idea of finding an artistic director to oversee “major alliances, new-play programs,” and the like. He is “open to thinking about UMS running it.”

He acknowledges that what’s missing from the Ann Arbor theater scene is professional theater of the very highest caliber. But he is admittedly vague about how he would address that deficiency, or whether he even wants to. He’s not sure whether the new Miller Theater should be strictly a presenting house for shows developed elsewhere or should occasionally produce its own plays.

Bollinger hopes to choose an architect by the end of this month. Construction of the new complex is expected to take several years. In the meantime, performing-arts organizations as disparate as UMS, Performance Network, the Ann Arbor Civic Theater, and University Productions, which manages most of the other stage spaces on the U-M campus, are watching developments closely.

A continuing commitment

One thing is clear: although Lee Bollinger’s determination is sufficient to build an Arthur Miller Theater, a continuing commitment will be needed if it is truly to live up to its name.

“Ann Arbor could have as rich a theatrical life as it does music if the University of Michigan, or some other group of subsidizers, will invest for ten years,” Russ Collins believes. “Theater has been strongly supported here in the past, but then debt and ambivalence set in, and it goes away. There needs to be a commitment of a significant period of time.”

Mark Lamos, former artistic director of the Hartford Stage Company in Connecticut and an adjunct professor in the U-M theater department, goes farther: “For a community such as Ann Arbor to support professional theater at the highest level, you need a group of people who believe in it so strongly they will be willing to fund-raise ceaselessly, choose and support artistic and management leaders, and be standard-bearers within the community for the institution. Every great regional theater began as a dream of pillars of the community.”

Such a theater, Lamos continues, also requires “large corporate pockets, large personal ones,” and an audience “that will sustain and support a variety of theatrical productions. An audience for an institution must be developed not through a hit-and-flop mentality but through a newly discovered conviction that the institution itself is more important than any one show—that its artistic mission is worth subscribing to.”

Finding and maintaining such support isn’t easy. Lamos left Hartford Stage in 1997, after seventeen seasons at its helm, because he’d grown tired of the ceaseless struggle for money. “Corporations were merging or downsizing, and the same group of wealthy arts devotees were being pursued by hospitals, universities, the symphony, the ballet, the museum. The community became too small to support my visions of artistic growth and institutional expansion.” Ann Arbor, he points out, is even smaller than Hartford.

It’s unclear, too, how a town the size of Ann Arbor, a four-hour drive from Chicago, the nearest major theatrical center, can attract the country’s finest actors, directors, and designers. Unlike musicians, who can fly in and out of a city in a matter of days or even hours to give a concert, theater artists typically need weeks of ensemble rehearsal to mount a production. Why spend that time in Ann Arbor?

Why spend time in Ann Arbor?

“We have to think about what could happen in Ann Arbor, in regard to theater, that could not happen in New York, Chicago, or London,” says Enoch Brater. “What can we allow theater professionals who are based there to do here that they can’t do there?”

Brater believes the university is the answer. In the absence of significant federal support, he maintains, universities today “are the great patrons of the arts. We can’t rely on Congress anymore. And it’s unrealistic to rely only on private support.”

It’s a vision Lee Bollinger shares—and he’s even writing a book on the subject. Last year Bollinger quietly provided $10,000 in university funds so that, under the auspices of UMS, singer Jessye Norman and choreographer Bill T. Jones could spend a week on campus working, in private, on a project they ultimately premiered in New York as part of the Lincoln Center Great Performances series. According to Ken Fischer, both artists reported afterward that they accomplished more “in one week in Ann Arbor than they could have in three months in New York.”

As Bollinger, Fischer, and their collaborators launch their new theater initiative, they can draw both inspiration and caution from the U-M’s own history. Back in the 1960s, generous university support enabled Ellis Rabb and his APA to develop productions in Ann Arbor that the company then took to New York. At the same time the Professional Theater Program, which brought the APA and other companies to campus in the 1960s, operated with little university control, as UMS does now.

Back in 1961, when university administrators invited Robert Schnitzer and Marcella Cisney to move to Ann Arbor from New York to run the PTP, they offered to build the couple a new theater. The pair turned it down. Writing about that gesture in a 1970 article for Players: The Magazine of the American Theater, journalist Glenn Loney observed, “The American Way is to build a theater in haste and then try to find out how to use it somehow, at leisure. [Schnitzer and Cisney] understood what few other artistic teams have: that you must first find out who your audience is, where it is, what it wants, what it needs—not always the same thing—and what varieties of creativity and service you can hope to present.”

Paradoxically, after Schnitzer and Cisney finally agreed to a new theater, and not long after the university built the Power Center, the couple left town. “It was retirement time, darling,” recalls Schnitzer, who, at age ninety-four, now lives in Connecticut. “I felt I’d paid my dues. It was a strenuous business, that dozen years. We worked like dogs.”

Schnitzer and Cisney were certainly entitled to their retirement, but without their leadership the PTP drifted and soon faded away. What’s to prevent history from repeating itself with the Arthur Miller Theater?

An Audience Ten Years Later

By September UMS had already sold over 1,000 complete RSC cycle tickets, and Fischer and Kondziolka are optimistic that the momentum can be sustained in subsequent seasons. “We think the time is right,” Kondziolka says. “We can help support the university by starting the labor-intensive, difficult work of building an audience, reestablishing a community, so that by the time the Arthur Miller Theater opens its doors there will be an audience ready, willing, and excited to accept this gift.”

That would be a tremendous accomplishment, and an essential prelude to the creation of a successful new theater. But will the Arthur Miller Theater continue to thrive ten or fifteen years down the road, once the novelty of the idea has worn off? Will a 600-seat theater be sufficient to offset the costs of producing or presenting world-class work, especially in a post-Bollinger administration whose focus is likely to be elsewhere? Will community leaders be willing, as Mark Lamos alleges they must, to “do anything on earth—including mortgage their homes” to keep the theater alive? Or was Tyrone Guthrie right when he decided that Ann Arbor couldn’t support the level of theater he had in mind?

At the outset, of course, the ball is in Bollinger’s court. It bodes well that the president himself is passionately excited by the prospect of bringing topflight theater to Ann Arbor. Shortly after Bollinger announced his plans for the building, Russ Collins sent him a note saying he hoped that Bollinger would listen “to his own inspiration and vision on this. It’s going to take that kind of leadership.”

There’s one other piece of advice that Bollinger would be especially wise to heed. It comes from Miller himself, who after all has chosen Ann Arbor as the one city to have a theater bearing his name. When the playwright learned last May that the regents had approved the Arthur Miller Theater, he wrote to Bollinger, “Who would have believed back in 1932–1934 when I was saving $500 to go to Michigan that it would come to this? Now to mount some memorable productions!”

Don’t miss the authors panel on January 28, 2015 at the Ann Arbor District Library, which includes Leslie Stainton as well as U-M faculty Martin Walsh and Leigh Woods. Moderated by UMS Director of Education & Community Engagement Jim Leiha. The panel will spotlight Staging Ground and also provide an updated look at the state of theater in Ann Arbor today.

Who Are We?

Théâtre de la Ville performs Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author at the Power Center in Ann Arbor on Oct 24-25, 2014. Photo by JL Fernandez.

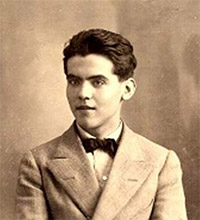

While I was working on a biography of poet, playwright, and theatre director Federico García Lorca many years ago, I was startled to discover that Lorca had planned to meet up with the dramatist Luigi Pirandello in Italy in 1935. The two intended to collaborate—but Lorca cancelled the trip after Mussolini invaded Abyssinia (it was one of the rare overtly political gestures of Lorca’s life), and the two men never met.

I’ve often wondered what would have happened if they had. For both playwrights shared, among other things, a fascination with the nature of theater. Lorca probed the topic throughout his life, in plays that contain plays and rehearsals within plays, plays whose cast lists include directors and actors and playwrights (including Lorca himself). He introduced all manner of theatrical claptrap into these works—puppets, masks, screens (behind which identities abruptly change), miniature stages, outlandish costumes and props.

Pirandello was similarly obsessed. You see it big time in Six Characters in Search of an Author, a play that, if done well, should produce something like imaginative whiplash in the audience. (I’ve only seen the work produced once, in a student production at NYU, with way too much scenery-chewing. But having seen Théâtre de la Ville’s exquisitely nuanced production of Ionesco’s Rhinoceros two years ago in Ann Arbor, my hopes are high.)

What’s real? Who’s acting?

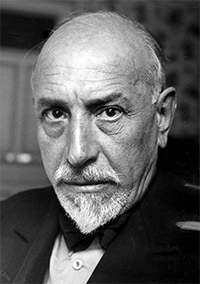

On left, Luigi Pirandello, and on right, Federico García Lorca.

What’s real? Who’s acting? Are the events and emotions we see onstage reality? Is what we experience and witness in “real life” acting? Can you trust what you see on a stage? In a conversation with your spouse or best friend or boss?

Aren’t these the questions that lie beneath the pleasures we associate with theater? (With film too, but I don’t think the experience is ever quite as acute on a screen.)

The setup for Pirandello’s exploration of theatrical artifice is straightforward: six purportedly fictional characters barge into a mostly empty theater to impose their story on a director and group of actors who are trying to rehearse a play. Actors become audience. Characters become actors. The layers multiply and confusions mount.

In line after line, we’re asked to consider the contradictions at the heart of play-making.

DIRECTOR: Then the theater is full of madmen, is that what you’re saying?

FATHER: Making what isn’t true seem true … for fun … Isn’t that your purpose, bringing imaginary characters to life?

Elsewhere the Father—one of Pirandello’s “six characters”—cries out that his story isn’t literature, it’s “life! Passion!” To which the Director responds: “That may be, but it won’t play.”

“What’s a stage?” a character asks toward the end of the play, and answers her own question. “It’s a place where people pretend to be very serious.”

The Empty Space

Exchanges like this abound—and make you question the theatrical enterprise and its conventions. Do we really need all the devices we’ve come to associate with the theater? The curtain and spotlights and scripts and applause? Peter Brook famously said (in his indispensable 1968 book The Empty Space) that in order for an act of theater to take place, all you need is for one person to walk across an empty space while another watches.

Brook published his book some 40 years after Pirandello wrote Six Characters, which opens on a stage whose atmosphere, Pirandello instructs, “is that of an empty theater in which no play is being performed.”

The Italian Pirandello grew up steeped in the venerable stuff of theater—the comic and tragic masks of the ancient Greek and Roman stage, the stock characters of thecommedia dell’arte. He understood (as did Lorca and that greatest of playwrights, Shakespeare) that identity is at the core of acting. As one of Pirandello’s six “characters” points out, “We all try to appear at our best, but we all know the unconfessable things that lie within the secrecy of our own hearts. We are not what we seem—even to ourselves.”

Don’t you change your personality according to the situation and your audience?

In another book I find indispensable, The Actor’s Freedom: Toward a Theory of Drama (1975), critic Michael Goldman probes precisely these questions. Identification is the “covert theme of drama,” Goldman writes. This isn’t simply a matter of actors identifying with roles but of “the making or doing of identity.” You watch an actor, onstage or on screen, and wonder where her private life stops and the public, performed one begins, what parts of herself we see revealed in her role.

“It should not be surprising, then,” says Goldman, “that the process of identification in this sense—of establishing a self that in some way transcends the normal confusions of self—is remarkably current as a theme in plays of all types from all periods, from Oedipus to Earnest to Cloud Nine.” Add Six Characters to that list.

And what about us? Are we characters—locked into our one and only story? Or actors, whose “solid reality as of this moment is destined to become the half-remembered dream of tomorrow,” as Pirandello’s Father puts it?

Questions to ponder, indeed. Endlessly.

Leslie Stainton’s most recent book is Staging Ground: An American Theater and Its Ghosts, a poignant and personal history of one of America’s oldest theaters, the Fulton Theatre in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

Propeller Blog: Behind the Scenes

Editor’s Note: Propeller performs Twelfth Night and The Taming of the Shrew in Ann Arbor, February 20-23. Leslie Stainton covered the company’s last visit to Ann Arbor in 2011 with Richard III. This post is a part of a series.

Photo: Actor Ben Allen took this photo inside the set.

From a Friday afternoon session with Nick Ferguson, production manager for Propeller, and U-M production and design students, these behind-the-scenes tidbits:

All of this had me marveling, again, at the audacity of touring. Propeller’s next U.S. venue is the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, where the big challenge will be maneuvering its towering wardrobes and chest of drawers up and down a thrust stage. Good thing they’re in Ferguson’s hands—he’s been working backstage in the theater since he was 17. Now “an old man,” by his account, he loves his work. “You never stop learning,” he says. “Especially in the theater.”

Propeller Blog: The Actor’s Freedom

Editor’s Note: Propeller performs Twelfth Night and The Taming of the Shrew in Ann Arbor, February 20-23. Leslie Stainton covered the company’s last visit to Ann Arbor in 2011 with Richard III. This post is a part of a series.

Photo: The Taming of The Shrew. Photo by Manuel Harlan.

I’ll confess up front I’d never seen Taming of the Shrew before. Never even read it. I had some gauzy idea—probably from Kiss Me Kate—that it was a happily-ever-after story about an ideally matched couple who couldn’t figure out they were meant for each other until they’d sparred around for two hours and wound up kissing.

I now know—or suspect—the reason I didn’t know the show is because it doesn’t get done all that much. And that’s because, like Merchant of Venice, it deals with things that make us very, very, very uncomfortable.

One of the first questions asked at the post-show Q&A last night: “Was it a comedy tonight?”

Answer, from a cast member: “The funniest thing about it is how stupid the men in the play are.”

In a book I return to regularly, The Actor’s Freedom, critic Michael Goldman argues that one reason we need theater is because of the actor’s freedom to handle “fearful materials…While on stage, the actor enjoys a kind of omnipotence, a privilege and protection not unlike that accorded sacred beings—whatever he is doing, whatever crimes he may appear to commit, he is not to be interfered with.”

You see Goldman’s idea played out to magnificent effect in this bracing, brutal show about domestic violence, staged as a play within a play—a merciful choice, as it turns out, because it releases us from what would otherwise be unbearable. (I dare anyone to smile at the show’s climactic image of Kate, as broken dog.)

Not that Propeller’s Shrew doesn’t have its moments of wild comedy or brilliant color or hip-thrusting ’70s tunes. But my guess is that’s not the part you’ll remember most. In the same week we marked the 50th anniversary of Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique, this production reminds us that Kate’s experience of spousal abuse is neither unique nor obsolete—as a number of cast members pointed out after last night’s show. Here’s Benjamin O’Mahoney (Grumio and Pedant) [start at 4:25 for related comment]:

Last night, as I watched actors play characters who were in turn playing characters, I realized again how vital this process is if we’re to confront and understand our basest selves. Identity is the “covert theme of drama,” Michael Goldman suggests. The fact that with Propeller, you’re seeing actors who played someone entirely different the night before only deepens the experience.

It’s a rare pleasure to see actors in rep like this, and to remember that this is how the theater once worked. Companies spent months on the road, traveling from town to town (we’ve got an old road house down the road from us in Adrian), switching roles nightly or sometimes twice in a day, layering roles upon roles. A huge nod of gratitude to Propeller for reviving the tradition and reminding us of the theater’s liberating powers.

Propeller Blog: Hauntings

Editor’s Note: Propeller performs Twelfth Night and The Taming of the Shrew in Ann Arbor, February 20-23. Leslie Stainton covered the company’s last visit to Ann Arbor in 2011 with Richard III. This post is a part of a series.

Photo: Twelfth Night. Photo by Manuel Harlan.

“Everything in the theatre, the bodies, the materials utilized, the language, the space itself, is now and has always been haunted, and that haunting has been an essential part of the theatre’s meaning to and reception by its audiences in all times and all places.” —Marvin Carlson, The Haunted Stage: The Theatre as Memory Machine

Among the ghosts I detected onstage Wednesday night—images and actions that reminded me of the last time I saw this company at work, here in Ann Arbor in 2011—were:

- Music—not recorded but performed onstage by the ensemble on an eclectic range of instruments, among them cello, clarinet, sax, bongo, wine glass and balloon

- Acoustic sound—no miked voices, thank god

- Chorus—the company is, for the most part, onstage throughout the show, donning half-masks to function collectively as both witnesses of and ghostly participants in the story

- Men playing women—I’d forgotten the unsettling pleasure of watching one gender impersonate the other (and, in the case of Viola-Cesario, male playing female playing male); this is how Shakespeare meant his plays to be seen, and while I don’t always love it, there is, as one actor said in last night’s post-show talkback, a “layering” that speaks to the ways we each layer ourselves in guises

- A quality of low-tech and handmade—of course this isn’t literally true (the show is designed and lit and costumed within an inch of its life), but you get the sensation this troupe of players has rather spontaneously come together on a platform to tell you a story, and they’re going to do it by hand, converting wardrobes into rooms, turning a chest of drawers on its side to function as a bar, picking up whatever musical instrument is at hand, grabbing costumes and props from a clothing rack, creating bird song with their own voices, acting out a tale as if they were kids in a playroom making their toys talk

- Syringe—remember Richard III with its sinister band of nurses? It came back in a flash last night when Sir Toby Belch produced a giant syringe to sedate Malvolio

There’s another way in which this production of Twelfth Night reminded me of Propeller’s last visit, and that’s the way it seemed to blend both previous productions—the somber, monochromatic Richard III and the zany Comedy of Errors—into a single show, at once monochromatic and zany. I’ve never seen a darker Twelfth Night, or a bleaker take on any Shakespeare comedy. Picture a score of actors, almost all of them in black, on a gray stage with sepia furnishings against a thundery sky. I kept waiting for unadulterated comedy to erupt from this gloomy space, and of course it did, but mostly in quick, jabbing bursts, and always with an edge.

And that’s as it should be, said actor Joseph Chance (Viola-Cesario) during last night’s post-show talkback. “There’s a lot of violence behind the play,” Chance told the hundred or so audience members who’d stayed behind to discuss the production with cast members. (I recommend it—and I’m not a big fan of talkbacks. There’s a second one tonight after Shrew.)

Malvolio’s humiliation is hilarious but also deeply cruel, Chance went on. It’s painful to behold. The ending of the comedy is not wholly sweet. Chance said he thinks this all “has a lot to do with Shakespeare’s ability to last through the years. He doesn’t pander.” The play is not unabashedly romantic, nor is it purely tragic—like life, it’s a mingling of both. When characters wonder if they’re going mad, they’re not being cute. There’s a real chance they are—and we literally hear that madness as it threatens to envelop them.

Here’s what assistant director George Ransley has to say about all this:

Caro McKay told me the other day that Shrew was the darker of the two plays on offer at Power. Now that I’ve seen Twelfth Night, I’m wondering how that’ll play out onstage. All I know is what actor Ben Allen said last night: “This show is monochrome. Shrew is disco lights like you’ve never had. It’s like drinking 10 espressos.”

Back in Town, and Loving It

Editor’s Note: Propeller performs Twelfth Night and The Taming of the Shrew in Ann Arbor, February 20-23. Leslie Stainton covered the company’s last visit to Ann Arbor in 2011 with Richard III. In this interview, Leslie chats with Propeller’s executive producer Caro McKay.

Photo: The Taming of The Shrew. Photo by Manual Harlan.

Caro McKay has been around the theater long enough to call herself “a dinosaur.” Now the executive producer of Propeller, she managed the English-language tour of the Peter Brook’s iconic Mahabarata back in the 1980s—a production students now learn about in performance studies classes, as McKay discovered to her surprise when she visited a class in U-M’s School of Music, Theatre, and Dance yesterday.

McKay’s been to Ann Arbor twice before—first with the venerable Royal Shakespeare Company nearly a decade ago, and then in 2011 with Propeller, the rambunctious, unpredictable, musically minded all-male troupe she launched a few years ago with the director Edward Hall. They’re all back in A2 this week with a pair of Shakespeare plays McKay says complement one another in dizzying ways—“because one is so harsh on love and marriage, and the other is so life-affirming about it.”

While crews were unpacking sets and focusing lights in the Power Center late yesterday afternoon, McKay took time to field a few questions by phone from her hotel room.

Leslie Stainton: What’s the best part about coming back to Ann Arbor?

Caro McKay: It’s the people. It really is. UMS is a fantastic host. And we’ve thoroughly enjoyed playing to the audiences. American audiences are very vocal. You let us know if you find it amusing or shocking. You tell us, and English audiences are rather restrained. It’s such a joy to have that interaction.

LS: What’s especially challenging about these two shows, Twelfth Night and Taming of the Shrew?

CM: Shrew is very funny but also very painful—there are very few kind words in that show. It’s the shorter, tighter, harsher of the two plays. For me it just passes in a moment, really. It’s riveting. And to follow up with Twelfth Night, which is a beautifully balanced bit of love with melancholy and humor—and also its own viciousness.

LS: Anything in particular we should be looking for in either play?

CM: Both shows are full of music. That’s very particular to Propeller, the way the actors are active musicians. I think there will be a lot for people to enjoy. I should just say very quietly that Act Two of Twelfth Night starts with a little bit of a tap dance routine.

LS: What about the sets?

CM: This time we’ve come back with a set that is shared between both productions, using wardrobes that you can walk into, out of, swing around. One wardrobe opens and has an organ. There’s an enormous great chandelier that is used in both plays. Twelfth Night can be quite black and white when we start in the beginning, in court, in this rather miserable little place … and then the color comes into it through the play.

LS: Are there certain moments where you’re especially curious to see how audiences react?

CM: I’m wondering how they will respond to the wedding in Shrew. So we’ll just wait and see what comments that might bring in. And to Petruchio and his servant. And I think the audience for Twelfth Night will enjoy the box tree scene—when Malvolio gets the letter to read. I think that is done in a rather different way. I’m very much looking forward to the comments. It was a rather lively debate last time.

What’s next in the Propeller pipeline?

CM: Our next two shows are Midsummer Night’s Dream and The Comedy of Errors. Popular titles. We’re building our audiences. Because a year after that, from the autumn of 2014 to 2015 we’re going to produce our history cycle. So we’re consolidating audiences, and then we’re going to sock ’em with a whole load of history. (Laughs.) Five plays, and we’ve decided that our version of the history cycle will include Edward III, which is attributed to Shakespeare.

LS: Any chance we’ll get to see it in Ann Arbor?

CM: We’d be so proud to. But I’m very very aware that Ann Arbor has had the RSC history plays! We would be only too proud—we love coming here already.

3 Questions for Director Wils Wilson

Editor’s note: This piece is a part of a series. You can also read Leslie Stainton’s essay on the power of place (or not) in theater.

Photo: Cast of The Strange Undoing of Prudencia Hart. Photo by Simon Murphy.

The Strange Undoing of Prudencia Hart is at Corner Brewery in Ypsilanti January 8-13. Our regular contributor Leslie Stainton interviewed the play’s director, National Theatre Scotland’s Wils Wilson.

Leslie Stainton: What happens to the theatrical experience when you move it into a pub (or other unconventional venue)? Does the audience change?

Wils Wilson: When the audience come into the venue for Prudencia Hart, there is a folk music session already going on. People are playing and singing, you can get a drink from the bar, you choose where to sit at small tables, and the performers come and talk to you in an informal way, asking you to do a simple task. So already the atmosphere is communal, convivial, playful and warm. We’re all in the same room together. It’s completely unlike the conventional theatre experience from the start, a different contract between audience and performers, one that allows space for a lot of intimacy, fun and emotional engagement.

A different space always brings with it a different audience. You get a conventional theatre audience, and you also get people who are intrigued to see how their bar or community hall will be used. There’s a sense of event, which has an appeal to a wide variety of people, so you often get a very mixed audience which is a huge advantage.

LS: How do Robert Burns, Border Ballads, and the poems of Robert Service speak to a global audience in the 21stcentury?

WW: David [David Grieg, creator of Prudencia] and I were attracted to the Border Ballads because they are fantastically dramatic stories of love, death, passion and the supernatural. They deal with such fundamental emotions and ideas they feel timeless. Robert Service’s wrote hugely popular tales of bold deeds in energetic rhyming verse again dealing with love, betrayal – big universal themes. It’s interesting, having played Prudencia now in a number of countries, that the idea of a folk tradition with stories of the devil and a borderland between this world and another, seems to be recognized wherever we go. The truth is that when you make a new piece, you just have to make something which feels necessary and relevant to you and which you yourself are truly interested in and challenged by – and if you make it well enough, it will speak to people wherever you go.

LS: Technology is increasingly defining our world. Where does live theater fit into this? How can theater help redress the imbalance we now seem in danger of experiencing?

WW: People will always be hungry for live theatre, music, dance, events. Nothing in the virtual world will ever replace seeing a real performer in front of you, seeing and feeling their emotion, seeing the sweat on their forehead.

So I think theatre should feel very confident just now, both in its own unique power and in how it engages with technological innovation. The two worlds don’t have to be seen in opposition. They will both continue to exist alongside each other, serving different needs.

The Power (or Not) of Place

Editor’s note: The National Theatre of Scotland performs A Christmas Carol on December 17 – January 3, 2016. The performance take place in an unconventional space: inside a box on the stage of the theater.

In my early twenties, I joined a children’s theater company and for half a year toured southeastern Pennsylvania putting on plays in elementary schools. I’d done my share of theater elsewhere, but nothing approached the energy of those performances. Every day we’d troupe off to another school to give our show and do a workshop. I’d been told children were the most demanding of audiences, but I never felt less than welcome anywhere we went, maybe because most kids were giddy with pleasure at the arrival of a bunch of costumed adults in their midst. (I played a dog.) It’s one thing to go to the theater, another to have it erupt in your cafeteria on a rainy weekday morning, much the way medieval pageants used to erupt in town squares.

We had little scenery and one change of clothes. I suspect we weren’t far from the kind of enterprise Peter Brook had in mind when he said the only thing needed for an act of theater to take place is for one person to walk across an empty space while someone else watches. The kids who sat cross-legged on carpet squares watching us perform certainly didn’t seem to distinguish between what we were doing and what took place downtown in the fancy 19th-century opera house our troupe called home—the kind of building Brook had in mind when he said of the theater: “Red curtains, spotlights, blank verse, laughter, darkness, these are all confusedly superimposed in a messy image covered by one all-purpose word.”

Photo (L to R): Palladio’s Olimpico, Radio City Music Hall, the Corner Brewery.

God knows the human thirst for stories has led to some amazing spaces: the ancient Greek amphitheaters with their literal sky, Palladio’s ornate Olimpico with its figurative one, Shakespeare’s Globe, the Sydney Opera House, Radio City Music Hall. But as pieces like Prudencia Hart remind us, it doesn’t much matter where plays are performed—or maybe it does matter, just not in ways we’ve been taught to expect. “Space that has been seized upon by the imagination,” writes Gaston Bachelard, “cannot remain indifferent space subject to the measures and estimates of the surveyor.” Performance transforms the sites we inhabit. I’ve often wondered if those elementary-school kids thought differently about their surroundings after we’d left. I hope so. Surely Ypsi’s Corner Brewery will be changed, perhaps in lasting ways, by what takes place inside it this January 8-13.

In a 2010 TED talk, Ben Cameron of the Doris Duke Foundation suggested that many purpose-built arts venues “were designed to ossify the ideal relationship between the artist and audience most appropriate to the 19th century.” Cameron and others argue that unless performing arts organizations rupture traditional thinking about arts settings, the whole culture of performance will stagnate.

It strikes me that what’s happening in the performing arts—where conventional performance venues are increasingly yielding to breweries, planetariums, armories, rivers (our own Huron!), and the local multiplex (witness the global appeal of the Met’s live broadcasts)—is not unlike what’s happening in the world of print publishing. Where either will end up is anyone’s guess, but we’re clearly changing the way we communicate—and with whom. When the Boston Lyric Opera presented two free outdoor performances of Carmen in 2002, more than 100,000 people showed up. A third of them were seeing an opera for the first time.

The National Theatre of Scotland proudly states on its website that it has “no building,” and therefore has “no bricks-and-mortar institutionalism to counter, nor the security of a permanent home in which to develop. All our money and energy can be spent on creating the work”—which they perform in places as varied as car parks, forests, Edinburgh’s Royal Lyceum, and Ypsi’s Corner Brewery.

Back when I toured with the kids’ theater troupe, we had no box office, no lobby, no lights, no stagehands, no drops descending from on high, no tickets or sound system or props— just ourselves and what we could carry in the back of a station wagon. Our audiences didn’t care. Maybe some of it had to do with their age. But I’m sure it also had to do with the enduring power of make-believe, the freedom that actors represent, and the startling discoveries that can happen when a familiar space is made new, and the audience with it.

Tweet Seats 2: Théâtre de la Ville: Ionesco’s Rhinocéros

Editor’s note: This season, UMS is launching a new pilot project: tweet seats. Read the complete project description and pre-interviews with participants here.

For the second tweet seats event, we saw Théâtre de la Ville: Ionesco’s Rhinocéros:

This week’s participants:

- Paul Kitti, writer for iSPY magazine

- Greg Baise, Detroit-based concert promoter, arts writer, and DJ

- Leslie Stainton, U-M School of Public Health Findings magazine editor and umslobby.org contributor

- Mark Clague, U-M Associate Professor of Musicology and UMS Board member

- University of Michigan social media intern Mollye Rogel

- Michael Kondziolka, UMS director of programming, scheduled to tweet at this event, was not able to participate. See his note about why below.

Read the whole tweet seats conversation here.

UMS: So, how did tweeting affect your experience of this performance?

Paul Kitti: For this particular performance, tweeting was most often on the back burner for me. It was impossible to tweet without missing something, as the performance was in French with surtitles (and I only know about three words in French…) The outcome, which I expected, was that I enjoyed the play as well as the twitter conversation, but the dialogue I missed in the process left some holes in the experience.

Greg Baise: I found myself thinking of tweets, but waiting for lulls to post them. Some tweets got away because I was deep into the play. Initially I was concerned that my tweeting activity would be a distraction to others. It turns out it was more of a distraction to myself!

Mark Clague: I was surprised by the conversational quality of tweeting Rhinoceros. Since we were reacting to a provocative narrative characterized by inference, juxtaposition, and an epic sense of language that seemed immediately referential and symbolic, many of the tweets searched for meaning. I paid attention to the hashtag and responded to several of the other tweet experimenters, but also to a couple of friends who either attended or just reacted to my observations. One such interchange led to a couple rounds of comments and ultimately intractable disagreement in interpretation. I found myself musing on the disagreement for days afterward and discussing the show face-to-face with another friend to clarify my own understanding. I didn’t change my mind and still prefer a more open interpretation connected to contemporary events, but my commitment to that understanding is richer and deeper for the tweets. Another thing I liked is that a question occurred to me the next day and I could tweet @UMSNews to get my question answered — YES, the set was transported from Paris to Ann Arbor. Finally, I attended the play a second time the next night and did not tweet. My experience was different — I became aware of how many people were speaking French in the audience. I don’t speak French, but gradually improved my understanding of the actors as the play progressed. Also, I sat in row 8 or so close to the stage, rather than tweeting from the back of the balcony. The emotional intensity of the play was much higher sitting so much closer. I was engaged both nights: the first felt a bit more intellectual (tweeting the show in this situation felt like taking notes at an exciting lecture) while the second was more raw and emotional. I’m guessing that my experience on night #2 was richer for having “researched” the play the evening before.

Leslie Stainton: If anything, this second experience of tweeting only confirmed my earlier antipathy to the form (if that’s the right word). It probably didn’t help that I saw the show near the end of the work week and after a glass of wine, so the dim lights and French dialogue and stratospheric tweet seats combined to send me into a bit of a nap. I felt oddly detached from the performance, and I suspect part of that had to do with the isolation I now associate with tweeting live theater. You’re apart from the crowd, with your little black box and too-bright phone. The production itself was gorgeous, provocative, beautifully acted, deeply meaningful. Some of this came together for me at the end, when I really did wake up with a “pow” and suddenly wished I could see it again, without the filter of tweets, and certainly from a better seat than the ones we had. (Didn’t bother me nearly so much with Aspen-Santa Fe, but this production needed to be seen up close, I think.) What “stuck” from the experience is my realization that I don’t want to tweet again–as I said to someone on my way out, I’d prefer to keep my brain farts to myself next time. But thanks for the experiment, and thanks to UMS, as always, for going about this so intelligently and carefully. And thanks for making it possible for those who DO get something out of this medium to keep at it.

Michael Kondziolka: I bailed on my commitment to be a tweet seater last night. Not because I didn’t want to try it out, but because if became clear that the General Manager of Théâtre de la Ville and the US tour producer of Rhinocéros wanted to sit with me at the opening night performance. I didn’t want to run the risk of offending anyone by creating a moment of “cultural misunderstanding.” After the show, I mentioned this to them both and they were, not surprisingly, first a little put off by the whole notion of tweet seats and, after more conversation, intrigued. I shared the tweet stream with them…and they seemed to like it. Interestingly, there seems to be very little commitment or conversation at the moment in Paris around the role of social media in connecting with audiences OR in building or attracting new audiences. At least this seems to be the case at TdlV. The GM of TdlV wanted as much information on the topic as I could give him…clearly he knows that he needs to look at these issues very seriously. Imagining what the experience of tweeting during last night’s performance would have been like gives me a rash. The complexity of the show…the layers of meaning and metaphor embedded in the text….how that meaning is delivered through the force of the acting and physical performance…PLUS the reading of super-titles (my French is only so-so)…was a lot to take in and make sense of from time to time. The idea of another layer — the processing of my thoughts and experiences and transmitting them in real time on a little illuminated keypad with my thumbs in real time — might have sent me around the bend. But I am still willing to try at an upcoming show!!

UMS: What do you think makes for a performance “sticky” (the performance “sticks” in your memory months or years later)? Do you think live tweeting a performance make it more or less likely to be “sticky”?

Molly Roegel: The quality of a performance in terms of acting, directing, music and set design, makes it “sticky” for viewers, as well as the relevance to them and how much they can personally understand. Live tweeting made this performance far less sticky to me as I could not pay attention to the subtitles, Instagram, Twitter, and the actual performance in any sort of way that would have allowed me to get the full experience of the play. I greatly enjoyed live tweeting but it was definitely not conducive to gaining the full scope of the play.

Mark Clague: Tweeting Rhinoceros has certainly made the experience more memorable or “sticky” for me. Four days later I can remember specific lines of dialogue and the emotion of the play remains vivid. I’ve had several conversations about the play with friends inspired by my twitter exchanges and reviewed my tweets archived on Twitter.com to review the performance, which reminded me of several personal responses that had begun to fade. Tweeting the show is definitely a source of distraction — I’m watching my cell phone screen at times rather than the stage. However, it’s not like I avoided all distraction the next night when I wasn’t tweeting on assignment. For the most part, I found that tweeting enhanced my attention and put me in a mindset to parse and understand the show. If the purpose of art is to get us to think and to think in unexpected ways, Twitter seems (for me at least) to serve this goal. If tweeting an art experience were to become more routine and typical, I wonder if some sort of compromise that takes the best of both my night 1 & 2 experience would be possible. One could tweet intermittently and engage with a broader conversation as the show inspired it. The brevity of Twitter leads to an immediacy and directness that might balance emotional reaction with analytical understanding.

Stay tuned for the next tweet seats event: Mariinsky Orchestra of St. Petersburg on Saturday, October 27.

How do you feel about using technology during live arts experiences?

Tweet Seats 1: Aspen Santa Fe Ballet

Editor’s note: This season, UMS is launching a new pilot project: an experiment at the cross-section of live performing arts and technology commonly known as “tweet seats.” Read the complete project description and pre-interviews with participants here.

For the first tweet seats event, we saw Aspen Santa Fe Ballet:

This week’s participants:

- Leslie Stainton, U-M School of Public Health Findings magazine editor and umslobby.org contributor

- Paul Kitti, writer for iSPY magazine

- Mark Clague, U-M Associate Professor of Musicology and UMS Board member

- University of Michigan Director of Social Media Jordan Miller

Read the whole tweet seats conversation here.

UMS: How did tweeting affect your experience of the performance?

Paul Kitti: Tweeting about the performance to people I knew weren’t in attendance made me more conscious about not only how I was perceiving the experience, but how others might. I also feel if I hadn’t been actively thinking about things to say about what I was seeing, I would have viewed it more passively – almost as if in a trance. I think it was a good thing to be viewing the performance analytically, but at the same time, it somewhat took away from the dreamy, ethereal effect of the ballet.

Mark Clague: I was looking forward to the performance with added anticipation knowing that I’d be participating in the Tweet Seats experiment. For me, the result was positive in that it focused my attention into distilling my experience into pithy statements that could be shared via Twitter. There certainly were times when I had to check out from watching the dance to attend to writing a tweet, although as it turned out, I think tweeting could easily have been limited to the breaks between dances. I did feel a bit uncomfortable tweeting, knowing that I was “breaking the rules” of typical concert behavior and that the glow of my smart phone’s screen on my face might distract others. This distraction factor would seem to be maximized in theatrical presentations and dance where the audience is in complete darkness and the stage is lit with colored lighting and other effects that are vital to the aesthetic of the performance. Dance / theater must be watched so it prompts the question of whether an instrumental concert might be more hospitable for tweeting as one can hear and look at a handheld device at the same time, plus audience lighting is low but not black for say an orchestral concert which would make screen glow less remarkable.

Leslie Stainton: I think I felt a bit the way I did in third grade, passing notes back and forth during class and hoping I didn’t get caught, meanwhile missing most of what the teacher was trying to teach. I’m afraid the experience has not changed my (admittedly biased) opinion that tweeting–and much of social media, for that matter–is a largely superficial, narcissistic activity beloved by people with a tendency toward ADD. I didn’t mind tweeting during intermission, but when I did it during the performance I completely missed what was happening onstage and disrupted any sort of narrative continuity. I found myself thinking more about how clever I could be tweeting than about what the pieces were trying to say to me. It kept me from delving more fully into the experience. I was “present,” yes, but mostly to myself and the small gaggle of people who were tweeting and following tweets. In retrospect, I think I got the lesser end of the deal.

Do we really need to “perform” as we watch performances? And what about those audience members who were spending their time tracking tweets rather than engaging fully with what was happening onstage? And what about the poor performers–going through their extraordinary paces to a distracted audience?

Jordan Miller: I think that the tweeting greatly enhanced my experience. I was able to share my thoughts with a whole variety of people, and to hear what they had to say. There were some people tweeting with a much greater knowledge of dance than I have, and that helped me appreciate aspects I wouldn’t have even thought about.

UMS: Did you expect this effect or are you surprised by this outcome?

Paul Kitti: I really didn’t know what to expect, but I wouldn’t say I was surprised. The ongoing tweet conversation made it feel more like a community experience, which I thought was cool.

Mark Clague: One surprise to me was that our tweeting didn’t really amount to a conversation. I think this was because we were sitting together at the back of the hall and thus our dialogue happened by turning to each other in response to a tweet rather than using twitter. Several times one person would turn to another at an intermission break to say “nice tweet,” or to discuss a topic that might have been too sensitive to post to the world — for example, the sexual overtones of the opening dance. In this sense, tweets did create a conversation and introduced me to new people, but tweets served as conversation starters for a face-to-face dialogue rather than the conversation itself. I can imagine a twitter section doing something similar in that those who choose to sit there are making a statement that they are engaged in the performance to search for things to share and discuss. Therefore, one doesn’t feel awkward in turning to a neighbor during the show to find out their twitter ID name and to ask a face-to-face followup based on some observation. I’d love to experience a performance in which several dozens of tweeters were engaged as I wonder how the momentum of the electronic conversation might be different. I made new friends at the Santa Fe performance via Tweeting and what surprises me is that I’d recognize them today if they sat next to me on a campus bus. Rather than substituting for person-to-person engagement with virtual friends, my twitter seat experience created real world connections.

Leslie Stainton: I’m not convinced the activity of tweeting enriched my experience of the concert in any way. I’ll try it again Thursday (though can’t promise how actively I’ll tweet during a show, in French, that has no intermission!). It certainly doesn’t seem to be the same sort of reflective activity as, say, blogging, or writing up a comment for the Lobby. Maybe I’ll change my mind? Doubt it!

Jordan Miller: I hadn’t expected the conversation to be so robust. Not only were the official “tweeters” engaging, but there were other audience members tweeting during intermission and before and after the performance as well, and that was very cool. In fact, I was able to meet up with a student who was at the show and talked to her afterward.

Stay tuned for the next tweet seats event: Théâtre de la Ville’s Ionesco’s Rhinocéros on Thursday, October 11.

Presenting: UMS Tweet Seats Pilot Project

TWEET SEATS EVENTS

Tweet Seats 1: Aspen Santa Fe Ballet. Find out what happened.

Tweet Seats 2: Théâtre de la Ville: Ionesco’s Rhinocéros. Find out what happened.

Tweet Seats 3: Mariinsky Orchestra of St. Petersburg. Find out what happened.

Tweet Seats 4: Find out what happened.

WHAT ARE TWEET SEATS?

This season, UMS is launching a new pilot project: an experiment at the cross-section of live performing arts and technology commonly known as “tweet seats.”

Tweet seats refer to seats in which tweeting is permitted during the performance.