Space is Flexible. Time Warps.

Lots of talk at Saturday Morning Physics on who Einstein is/was and what he represents.

Composer Philip Glass: “As I worked on Einstein on the Beach, I began to see Einstein as a poet.” (Interestingly, Glass sees himself as “kind of a failed scientist.” He admits he wanted to be three things as a kid: musician, scientist, dancer. Of the three, he became just one.) Glass also notes that Einstein was the first scientist to become a celebrity.

Physicist Sean Carroll, of the California Institute of Technology: Einstein’s theories changed the definition of time. They taught us that “everybody’s watch reads personally.”

Theoretical physicist Michael S. Turner, of the University of Chicago: “Einstein changed the way we think about something that was very basic—space and time.” Turner teaches a course on Einstein and relativity. The gist of the course, Turner says, can be summed up in two sentences: “Space is flexible.” “Time warps.”

On those last two sentences, here’s UM’s Martin Walsh, a theater professor at the Residential College, on the time-warping experience of watching Einstein on the Beach at the Power Center on Friday night:

Inside Einstein on the Beach: Guest Blog by Lindsay Kesselman

Editor’s Note: Lindsay Kesselman will sing with the Phillip Glass Ensemble for the duration of the 2012-2013 international tour of Einstein on the Beach. She’ll also be guest blogging on umsLOBBY.

Photo: At rehearsal with Robert Wilson. Photo by: Einstein Assistant Director Ann-Christin Rommen.

Excitement is brewing this week in Ann Arbor and seems about ready to burst. Einstein on the Beach is officially beginning again, for the first time in twenty years, and after much anticipation….today. All of our preview performances this weekend are sold out, and we’ve been told that people are coming from 30 different states to see what we have created. The thought is thrilling, humbling, and sobering all at once.

After spending these last two weeks in intensive technical rehearsals, we are becoming the people we’ve read about, seen in photographs, and admired in videos from previous productions of this miraculous piece. You can recognize us by our crisply pressed white shirts, tell-tale black suspenders, indispensable converse shoes, and unmistakably whitened faces. And we now know first-hand what to expect from the legendary Robert Wilson’s lighting rehearsals.

Each day we spend approximately 12 hours at the theater, in full costume and make-up, and though our hours are long and grueling, our amazing stage crew works seemingly non-stop, arriving before us and leaving after us, to ensure smooth rehearsals the following day. We are so grateful for them and absolutely couldn’t do anything without them.

The last two weeks have been spent going over every moment in every scene with a fine-toothed comb, so that Bob could light every hand, face, prop, and set piece with remarkable precision, artistry, and eye for detail. The lighting for this opera is breathtakingly beautiful and unlike anything I have ever seen or could possibly imagine. There are so many moments I wish I could see from the audiences’ perspective!

The process of working with Bob has been completely awe-inspiring, and I feel the power he exudes every time he enters a room. He is a director whose vision is perfectly clear at all times, and the passion and dedication he brings to his work transforms everyone around him.

In these rehearsals we have learned to think as a group, rely on each other, trust ourselves, and discover hidden reserves of energy we didn’t know existed. We have learned and memorized the music, we have embraced the new style of movement and commanding attention on the stage, and we are ready to accept the torch and make this piece our own in the coming days, weeks, and months.

In moments when we have not been needed on stage, we could be found obsessively chanting numbers, reviewing memory with our dozens of flash cards, inspecting our make-up in hopes of one day being able to re-create the beautiful work done by Luc and Cory, and stuffing our faces with the (much-appreciated) food and drink provided by UMS to keep our strength up during these long days.

Today we assume the responsibility and utter joy of becoming the new Einstein cast, and it is our honor to share this remarkable work with you. I am personally so grateful that our journey begins here and cannot wait for you to see what we’ve been up to!

How to produce Einstein on the Beach

Photo: Section of a drop in Einstein on the Beach.

Photo: Section of a drop in Einstein on the Beach.

Mel Brooks’s “Producers” they’re not. “No way we’ll become become rich on this,” Linda Brumbach said yesterday at UM’s B-School in a 90-minute public conversation about the ins and outs of producing Einstein on the Beach. Brumbach is the head of Pomegranate Arts, the tiny production company that’s taken on the near-impossible task of bringing Einstein to the stage here in A2 and in 10 other venues around the world. The tour ends in Hong Kong in March 2013, and Brumbach says she’ll consider it an artistic success if “Bob, Phil, and Lucinda get the piece they want.” That’s Robert Wilson, Philip Glass, and Lucinda Childs, the artists who gave birth to the monumental opera in 1976 and have seen only two revivals since then.

After yesterday’s session, I understand why. The 1976 premiere of Einstein cost $750,000, and Wilson had to put huge chunks of that sum on his American Express card and then plead with Amex to waive interest charges. Glass had to sell the score to offset costs.

This week’s production costs a staggering $2.5 million—and that doesn’t include touring expenses. UMS President Ken Fischer said that for UMS to make money on this, “we’d have to charge $500 a ticket, and we’re not about to do that.” “I don’t think anyone can actually make money on Einstein on the Beach,” Brumbach added.

Why the exorbitant price? Consider:

• The model for Einstein’s sets costs as much as $90,000

• It takes three freight containers to ship the production

• Props include 600 pounds of dry ice

• Costumes include 30 pairs of converse high-tops

• Tech rehearsals require three solid weeks at the Power Center (the other day, Wilson spent 14 hours lighting just one scene)

• Load-in at each new venue takes three days

• Contracts for touring venues contain a 26-page technical rider

• European venues are operating in euros

• 35 press agents are needed to promote the opera worldwide

• In A2, the production requires 65 company members and 35 local stagehands

For Brumbach, the dream of producing Einstein is 12 years in the making. She first set out to revive the opera in the early 2000s, but 9/11 and its aftermath halted those plans. In 2007, it looked as though New York City Opera would partner with Pomegranate to stage the work, but the opera company’s budget was slashed and the season cancelled. A promised Paris production went nowhere. It wasn’t until UMS’s Michael Kondziolka said to Brumbach a year or two ago, “We’ll do it,” that she saw a way.

UMS is one of seven co-commissioners—three in the U.S., one in Canada, the rest overseas, and all of them “friends,” says Brumbach—who’ve gone in with Pomegranate to make this week’s historic preview performances (and subsequent tour) happen.

They’re still teching inside the Power Center as I write. One last drop is being repainted in Detroit and will be delivered to the theater at 2 pm Friday. There’s more than an element of brinksmanship to all of this. I wouldn’t want to be in Brumbach’s shoes just now, but I’m quite eager to witness her dream-come-true this weekend.

Not Quite-Live-Blogging Robert Wilson and Philip Glass Conversation at the Michigan Theatre

Editor’s Note: Last night’s Penny W. Stamps Speaker Series featured a conversation with Einstein on the Beach co-creators Philip Glass and Robert Wilson. Anne Bogart, acclaimed theater director, moderated the conversation. Leslie Stainton blogs about the event below.

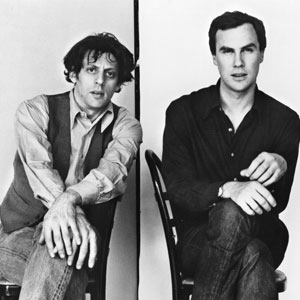

Photo: Philip Glass and Robert Wilson.

3:45 pm*

I have to ask someone to move over a seat so that there’s room for my two friends and me. The place is jammed, top to bottom. Balcony, orchestra. There’s a sound guy behind me, and a videographer up front, and dozens of people are milling about in the aisles. You’d think the Golden Globes were taking place.

*Times are approximate

4:15 pm

After a round of introductions, director Anne Bogart, who’ll moderate the conversation, takes the podium. She tells us A2 is the place to be this coming week, because we’ll get a window into the “extraordinary trajectory of this production.” She reminds us that since its inception in 1976 and its last iteration in 1992, “our lives have become faster and faster.” Einstein, she notes, “changes the time signature”—a suggestion I find beguiling.

4:20 pm

We see documentary video footage of Glass and Wilson, with snippets of the original 1976 production. Either Glass or Wilson—I can’t remember which—describes Einstein as “the god of our time.” I wonder if that holds for the 21st century?

4:30 pm

Wilson and Glass take the stage to rapturous applause. Bogart mentions the ovation. “We haven’t done anything yet,” Glass mumbles. Laughter. Surely I’m not the only one thinking, “Oh, but you have.”

4:35 pm

Wilson describes the early stages of Einstein’s development. He and Glass shared a “common sense of time and space,” he remembers. They agreed on a common megastructure and a total time length. Each man followed the same structure but filled it in different ways. This is a theme Wilson will repeat throughout today’s conversation: Form—whether of something as big as an opera or as minute as an actor’s gesture—is less important than how it is filled. Appearances to the contrary, the form of Einstein is “very classical, very formal,” Wilson says, and something we should all recognize—theme and variation.

4:40 pm

Glass observes that every time they’ve produced Einstein—in 1976, 1984, and 1992—they’ve drawn huge numbers of young audience members. Judging from the crowd in the Michigan, it’s still true.

4:50 pm

There’s talk of how radical it was in 1976 to produce an abstract work like this in a conventional setting like the Metropolitan Opera House—at a time when lofts and street theater were the rage. (Wilson remembers thinking, “What’s wrong with illusion?”) He and Glass had to rent the Met for a day in order to put on Einstein that day. “We didn’t actually have the money,” Glass interjects. Because of the opera’s five-hour duration, without intermission, the Met bars made a killing. I’m reminded that the Power Center can’t sell booze, which seems a pity.

5:00 pm

Wilson urges audiences to come and go during Einstein the way they would in a park. “It’s always going on, something is always happening.” This way, there’s “not so much difference between art and living. If you want to sit for five hours, that’s OK. If you leave in the second act and come back in the fourth, you’re not lost. It’s not like Shakespeare.” Much laughter.

Glass adds, “The audience completes the work. The piece by itself doesn’t work.”

5:10 pm

On process, both Wilson and Glass caution against knowing too much when you embark on a project. Glass: “If I know what I’m doing, then I don’t have anything to do.” Wilson: “As I got older, I learned that if I pre-decide, I often waste time, instead of going in with no idea. Let the beast talk to you instead of you talking to it.” Both say the starting point of a piece doesn’t matter. The process itself becomes the content.

5:15 pm

Glass gets a laugh when he recalls how John Cage once chided him: “Philip, too many notes.”

5:20 pm

Performer and choreographer Lucinda Childs joins the conversation. Bogart speaks of how riveting Childs’s performance in Einstein was when Bogart first saw it in 1976 and again in, I think, 1992. Bogart’s referring to the moment when Childs spends 20 mintues crossing the stage back and forth on a diagonal. For years Bogart wondered why she couldn’t take her eyes off Childs, what Childs had to teach her about the arts of acting and directing. The answer—proposed here by Wilson—seems to be that as an actress, Childs filled every single moment. He talks of the “sheer stamina” the production demands of actors, which is matched, he adds, by the stamina of watching it.

5:25 pm

Wilson unlocks something for me when he speaks of the difficulty some critics have with Einstein because it’s abstract. We can accept works by Jackson Pollock as abstract, Wilson explains, but not something we call “opera” or “theater.” Nor do conservatories or theater schools tend to include the term “abstraction” in their curricular vocabularies. Wilson says abstraction is liberating for him. This seems critical to understanding what we’re about to see onstage this week.

5:30 pm

Questions from the audience. Long lines form in both aisles. The first questioner wants to know why the opera has such short runs whenever it’s produced. Money, Glass answers. Wilson claims the same production will cost 3-4 times more to mount in New York City than in Paris. A stagehand at Carnegie Hall, he adds, makes more money than Obama.

Someone asks for advice for young artists. “Keep working,” Wilson urges. He’s not being facetious.

A stage-design student wants to know how to meld set, costume, and lighting design. Wilson notes that in conventional opera staging, sets often distract from sound, and vice versa. The question designers and directors should ask, he believes, is “How can what I am seeing make me hear better? Can I create something onstage that makes me hear the music better than I do when my eyes are closed?”

5:40 pm

In response to a long-winded and confusing question about novels and language, Wilson is more than generous. He speaks of his work with autistic children, of the difficulties that ensue when actors inject their own emotions and feelings into texts rather than letting the texts speak and audiences decipher their meaning for themselves. He says it’s “OK to get lost” when you’re reading a complicated novel or listening to a Shakespeare sonnet (or, we can infer, watching something like Einstein). “TV has changed our way of thinking. Do you understand? Do you get it?” TV is forever asking that, forever explaining. Wilson: “It’s OK to get lost.”

5:42 pm

The visual space in Einstein is organized in three very traditional ways, we learn. Portraits, still lifes, and landscapes. Bogart mentions the influence, as well, of vaudeville, and Wilson agrees, noting that Chaplin and Keaton are both inspirations.

5:45 pm

The session ends with an exchange that must warm the hearts of many in the crowd. An audience member asks why Wilson and Glass chose to reconstruct the show here in A2. Glass cites the financial practicalities of mounting a huge production like this in a noncommercial theater and mentions the educational benefits for both audience and cast, crew, and Glass and Wilson themselves.

But Wilson delivers the money quote. Ann Arbor, he says quietly, “is one of the cultural strongholds of this country.”

With that, Bogart ends the discussion and sends us out into the cold. The sun has set, the sky is a pale lavender, and the street lights are glittering. The place feels even brighter than it did two hours ago, in full daylight.

Whose Einstein? (Who’s Einstein?)

For a concept that underpins much of life as we know it—including, science historian Peter Galison reminded listeners yesterday, GPS and satellite technology—Einstein’s theory of relativity is hard to grasp, at least for this non-physicist. At yesterday’s Institute for the Humanities lecture in Rackham Amphitheatre, Galison laid out both background and context for Einstein’s radical rethinking of time as a relative rather than an absolute phenomenon. Galison revisited some of the myriad way scientists had grappled with the mysteries of time pre-Einstein, including a subterranean Center of Pneumatic Time in late-19th-century Paris, which literally attempted to pump time through the city, leading one poet to complain that the constant pulses of air he was experiencing had sapped his creativity.

For a concept that underpins much of life as we know it—including, science historian Peter Galison reminded listeners yesterday, GPS and satellite technology—Einstein’s theory of relativity is hard to grasp, at least for this non-physicist. At yesterday’s Institute for the Humanities lecture in Rackham Amphitheatre, Galison laid out both background and context for Einstein’s radical rethinking of time as a relative rather than an absolute phenomenon. Galison revisited some of the myriad way scientists had grappled with the mysteries of time pre-Einstein, including a subterranean Center of Pneumatic Time in late-19th-century Paris, which literally attempted to pump time through the city, leading one poet to complain that the constant pulses of air he was experiencing had sapped his creativity.

Time zones, telegraphed time, Paris vs. Greenwich time, time signals, coordinating clocks at the train station just outside Einstein’s house in Bern: all of these set the stage for the 1905 theory that changed existence as we know it and led, among so much else, to the nuclear age. Galison notes that as early as 1921, Einstein had wormed his way into the minds and work of artists like Hannah Hoch and William Carlos Williams, who saw the then-42-year-old physicist as the emblem of a new modernity. (Galison also played a 1931 recording of Rudy Vallee singing “As Time Goes By,” whose original first stanzas, excluded from Casablanca, pay tribute to Einstein.)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gKW0QZgi79M

Philip Glass says that as he and Robert Wilson were developing Einstein on the Beach, Wilson remarked that he liked Einstein as a character “because everybody knows who he is.” Glass adds, “In a sense we didn’t need to tell an Einstein story because everyone who eventually saw our Einstein brought their own story with them. … The point about Einstein was clearly not what it ‘meant’ but that it was meaningful as generally experienced by the people who saw it.”

After hearing Galison’s talk yesterday—parts of which I’ll admit sailed right past me—it dawned on me that by sitting through a five-hour production exploring these ideas, by hearing Glass and Wilson speak this Sunday, by attending next week’s Saturday Morning Physics session with Glass, I may finally make some headway toward understanding Einstein’s famous theory—and if not understanding it, at least paying closer attention to the questions it seems to raise. Such as:

• How does Einstein’s theory play out in daily life? How and when and where am I aware of time lengthening or collapsing, and to what effect?

• What happens to time inside a theater? Inside this theater, during a five-hour, non-narrative work with repetitive sequences of image and sound?

• To what extent do I confuse the measurement of time—the clock on my wrist or computer screen, the litany of appointments on my calendar—with actual time? What’s the difference?

• Does technology shorten or lengthen our lives? If, for example, pilots who routinely fly around the world age more slowly than the rest of us, what happens to space travelers? To tweeters? To people who Skype?

• Is it at all possible to move backward in time?

Three Trucks, 28 Crew Members, 37 Performers: Einstein on the Beach Load-in at the Power Center

Photo: A moment on the train from Einstein on the Beach.

Inside the Power Center 14 days before the opening of Einstein on the Beach, it’s not immediately clear that this is, “hands down, the biggest show ever” to hit this auditorium, as UMS programming manager Mark Jacobson told me shortly before we entered the theater. But after an hour or so of listening to production manager Will Knapp talk about the challenges of mounting the giant opera here in Ann Arbor, I began to see what Jacobson meant.

Knapp met with around 30 UM stage management and design students on Friday in the first class of a semester-long course on stage production taught by Gary Decker of the UM School of Music, Theatre & Dance and other faculty. Collectively, the students brought a decent amount of expertise to the session, so there was lots of technical talk about things like trap doors, cyclorama lights, tracks, cues, headsets, and so on.

(“Is it hard to focus when you’re calling a show that’s five hours long?” one student wanted to know. “It kind of is,” Knapp said, and mentioned that, among other things, the opera’s three stage managers have to coordinate toilet breaks.)

Decker, who teaches theater production classes, told the students that scenery for the show arrived in Ann Arbor in two 53-foot trailers on the day after Christmas and had to be “shoehorned” into the Power Center—whose stage area is small as opera houses go—with “literally inches to spare.” It’s taken some 40 crew members, both local and touring, to load in Einstein’s sets, costumes, and props, and hang and focus lights. The lighting for the cyclorama alone is so complex crews need to devote an entire day to installing it.

The cast, who spent all of December rehearsing Einstein, arrived this Sunday, January 8. Final rehearsals start today, with mornings devoted to technical issues—setting light and sound levels, timing cues, perfecting scene shifts—and afternoons and evenings to a rigorous runthrough of the opera, in full makeup and costumes, under director Robert Wilson’s exacting eye.

An Auteur at Work

Knapp has worked with Wilson off and on for two decades and describes him as more of an auteur than a conventionally collaborative stage director. “It’s all him. Everybody is a helper. You really are an extension of his fingers.” An architect before he turned to theater, Wilson typically begins work on a production by sitting with an empty stage, Knapp said. “He treats it like an empty canvas. He creates pictures and then tries to animate them. He’s not trying to reinforce a narrative but to make interesting pictures for himself. This is the start of his process.”

Wilson makes sketches on copy paper, often in charcoal. It’s a rudimentary way of communicating with his production team “but also very specific,” Knapp went on, with particular attention to spatial rhythm and proportion. Eventually real drawings emerge, and then a model—components of which Knapp hauled from boxes on Friday and spread out on a table for the students to inspect: a meticulously built miniature clock, a train, a multi-story gray space machine.

Knapp also showed the students the 130-page “project book” he and others use to make sure each production of Einstein adheres to Wilson’s fastidious vision. The book includes directions on things like the angle with which a given character should gaze at the floor and the precise distance a character should maintain between her right arm and the back of the chair on which she’s sitting.

“Bob doesn’t collaborate,” Knapp said. “He is the author, the costume, light, set designer. The best way to work with someone like him is to listen really hard and do exactly what he says.”

The payoff should be apparent on January 20, when Einstein opens its three-preview-performance run in Ann Arbor, the kick-off to a 30-performance tour that will take the massive opera to France, Italy, London, the Netherlands, Toronto, New York, and possibly Hong Kong.

What might Wilson demand once he gets to the Power Center this week? The first thing Knapp expects this acknowledged wizard of light to do is to examine every single light in the theater—there are hundreds of them, plus a whopping 3,000 light bulbs spattered across the surface of the towering space machine. Knapp suspects Wilson will also ask for at least one drop to be repainted.

Says Decker, who’s seen a number of Wilson pieces, “I’m looking forward to Robert Wilson.” He adds with a grin, “But it’s going to be tough sledding to get to opening night.”

Inside Einstein on the Beach: Guest Blog by Lindsay Kesselman

Editor’s Note: Lindsay Kesselman will sing with the Phillip Glass Ensemble for the duration of the 2012-2013 international tour of Einstein on the Beach. She’ll also be guest blogging on umsLOBBY. Einstein on the Beach is part of Pure Michigan Renegade.

For those of us in the chorus, the anticipation has been building for six months. Six months of waiting, imagining, preparing, and eagerly counting down. Now, on December 27th, it is crazy to think that the anticipation is over and we are already completely immersed in Einstein, having just finished three weeks of rehearsal in New York.

For so long, this project existed on a distant horizon, one it seemed we would never reach….for months now friends near and far have been asking, “So…how’s Einstein going?” …eager for details about the music, the people, the challenges, and I have had to respond, “Oh…actually, we haven’t started yet.” Now, and in the blink of an eye, we are well underway, having learned all of the music, all of the original staging, and even having begun to memorize much of the material. Where did the time go?

The last three weeks are a blur of long, satisfying days, approximately 90 hours of rehearsal, of becoming familiar with and beginning to master our music, learning to move in completely foreign and fascinating ways, and finally: being able to imagine what it will feel like to sing this show from start to finish.

To say that it is a challenge is a HUGE understatement. The piece makes physical, vocal, and mental demands which are completely unique and which are definitely creating new standards for us as artists, performers, and people. We sing faster, more continuously, and more rhythmically than we ever have before, all while moving in incredibly intricate, stylized, and intentional ways, and the mental focus we need to maintain for four-and-a-half hours (the duration of the performance) is truly staggering. Every night in New York we left rehearsal feeling drained, mentally and physically, without an ounce more energy to give. And…it felt fantastic.

There are a few singers in the chorus, as well as instrumentalists, stage managers, and sound specialists, who were part of the 1992 tour (and earlier productions) of this piece. Throughout our rehearsals, these members of the chorus shared memories with us about their past Einstein life (or lives). From spending hours in rehearsal holding uncomfortable positions while Robert Wilson got the lighting just right, to audiences cheering in Japan and throwing tomatoes in Barcelona, we heard countless stories and began to understand the enormity of this piece re-constructed now, and what a huge impact this experience will have on all of our lives.

The first day that Dan, our front-of-house mixer, sat in on rehearsals with us, he was moved to tears while hearing this music again after such a long absence. Our producers from Pomegranate Arts came to rehearsal regularly after long days at the office where they had been working on all of the many details for our tour, just to bask in the singing, the dance, the acting. They have been dreaming of this revival for the last 12 years, and FINALLY it is coming to fruition. Seeing these reactions, we felt even more determination to do this piece justice. For Dan, for Pomegranate Arts, for Lucinda, Robert, and Philip, for all of the people who have loved this piece for a long time, and for those lucky new fans who will be intrigued for the first time.

It is a huge responsibility, and one we are taking very seriously. All of us, singers, dancers, and actors alike, are pushing ourselves to the limit. Even when our directors are satisfied and pleased with our progress for the day, we keep pushing, insisting we can do better- sing more perfectly in tune, make rhythmic changes more seamlessly, and memorize more quickly.

I feel so fortunate to be surrounded by such warm, friendly, diligent, fun-loving and extraordinarily talented group of people. We are having a blast and becoming a family, and it will be a privilege to spend the next year and a half traveling the world and singing this piece with them. Next stop: Ann Arbor, where we will meet Robert Wilson, rehearse for 3 more weeks in the Power Center, and bring Einstein on the Beach to the Midwest!

Have a question for Lindsay, or curious about something to do with Einstein on the Beach? Use the hashtag #askeinstein on Twitter or comment below.

[VIDEO] Einstein on the Beach – Original Creative Team

This winter UMS is presenting a 10-week, 10-event ‘renegade’ series focusing on thought-leaders and game-changers in the performing arts.

The opera Einstein on the Beach opens the series. Widely credited as one of the greatest artistic achievements of the 20th century, Einstein launched director Robert Wilson and composer Philip Glass to international success when it was first produced in Avignon, France in 1976.

In this video, featuring the original creative team, Philip Glass remembers the first night of Einstein, Robert Wilson sits next to Arthur Miller, and Lucinda Childs recollects the “Supermarket Speech.”

Part of Pure Michigan Renegade.

The 2012 production of Einstein on the Beach was commissioned by: University Musical Society of the University of Michigan; BAM; the Barbican, London; Cal Performances University of California, Berkeley; Luminato, Toronto Festival of Arts and Creativity; De Nederlandse Opera/The Amsterdam Music Theatre; Opéra et Orchestre National de Montpellier Languedoc-Rousillon. Produced by Pomegranate Arts, Inc.

Robert Wilson: Video 50

Robert Wilson fans will have much to do in Ann Arbor this winter.

UMS is presenting preview performances of Einstein on the Beach, an opera by Robert Wilson and Philip Glass, January 20-22. Absolute Wilson, a film which chronicles the epic life, times, and creative genius of theater director Robert Wilson, will be screened on January 9. The film screening is free.

Photo: Robert Wilson. “Video 50,” 1978. Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

In conjunction, UMMA’s Video 50 curates Robert Wilson’s “smaller-scale” experiments in video. Guest Curator Ruth Keffer describes the exhibit:

Video 50 consists of a randomly arranged set of 30-second “episodes”; counting occasional repeats and alternate versions, the 50 pieces of the title number nearly 100. Some of these episodes are static to the point of resembling still-lifes; others are self-contained vignettes that begin and end—or seem to end; any narrative resolution is teasingly withheld. With its use of early video techniques and the highly stylized, fashion-world look of its actors, Video 50 seems dated, but the way in which Wilson wields his domestic-gothic vocabulary is classic surrealism: everyday objects and settings made mysterious or comical or alien by their bizarre juxtaposition to one another, and by an equally nonsensical and cheerfully manipulative score of music and sound effects.

Read the full article in UMMA Magazine.

RENEGADE Contest – Win Tickets!

This winter’s Pure Michigan Renegade series, a 10 week, 10 event series focusing on “renegades” examines thought-leaders and game-changers in the performing arts.

What’s a renegade to you? How do you know when a performing arts work or artist is truly game-changing, experimental or history-making?

Give us your answer in 7 words to enter to win tickets!

THE DETAILS

WHAT: UMS “What’s a Renegade?” Contest

REQUIREMENTS: Your definition of a performing arts renegade artist or work in exactly 7 words. This contest is free. Entries judged on creativity, renegade-ness.

DUE: January 12th, 12PM Noon.

PRIZES:

1st place: Pair of tickets to your choice of concert at San Francisco Symphony’s American Mavericks with Michael Tilson Thomas.

2nd place: 2 very special reserved seats to Robert Wilson & Philip Glass at the Michigan Theater as part of the Penny W. Stamps Speaker Series. Conversation led by acclaimed theater director Anne Bogart.

HOW TO ENTER:

(1) Tweet your entry @UMSNews

(2) Add your entry as a comment on UMS’s Facebook page during the contest period. You must label your comment as a Renegade Contest entry.

(3) Add your entry as a comment in the comments section below.

Winners to be announced by January 12th, 5PM. Questions? Ask in the comments below.

Bonus Video: Renegade composer John Cage at a game show in 1960.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?&v=7KKE0f1FGiw

Thanks to everyone who entered! Our winners, selected by UMS staff, are:

1st Place

Lesley Criscenti

Bold experimentation,

freewheeling risk,

opening minds meet.

2nd Place

Elle Bigelow

Apostate creativity

Distorting the norm

Delicious tension

Check out more of our favorites here. What was your favorite 7-word renegade definition?

Why Renegade? with Time-Warping Powers

Photo: Philip Glass and Robert Wilson.

Photo: Philip Glass and Robert Wilson.

There was much to mull over at last Monday night’s roundtable discussion of the Renegade series. Panelists talked of the series as a 10-week, 10-performance “journey,” an “adventure.” They described it as a conceptual frame “for exploring how artists create innovative work.” (If the series does nothing else, I hope it gives us a new vocabulary for talking about “innovation,” that tired phrase.) Danny Herwitz of the UM Institute for the Humanities made a compelling case for a uniquely American brand of “renegade,” invoking figures as disparate as Whitman and Aaron Copland, Emerson and Clint Eastwood, John Cage and John Wayne. “In America a renegade is someone who refuses the templates of convention,” Herwitz said, and issued something of a challenge when he suggested the series might allow us to imagine the country’s future at a time when many of us have lost faith in that future. “To remember the voices of these composers”—Cage, Copland, Philip Glass—“is to remember something about the experiment in which we were born.”

But more than anything I came away from the discussion thinking about time. Maybe it’s because I’m into my fifties and ever more keenly aware I’m on the short end of the lifespan stick. I think of the old woman in Emily Mann’s play Annulla who says, “Everything has gone by so fast.” Maybe it’s the world we inhabit, this cacophany of blogs and tweets and video clips, information coming at you so fast you can barely skate the surface. Increasingly I find myself wanting silence and space, the ability to make a connection that doesn’t involve an electronic gadget.

In his marvelous book Einstein’s Dreams, the novelist and physicist Alan Lightman writes of the ways that time bends experience—a phenomenon we came to understand with particular clarity in the last century, thanks in large part to Einstein himself. Lightman describes how time moves “in fits and starts,” how it “struggles forward” when one is rushing a sick child to the hospital and “darts across the field of vision” when one is eating a good meal with close friends “or lying in the arms of a secret lover.”

It is this sense of time as somehow malleable—and also manipulable—that marks many of the works in the Renegade series, most obviously, perhaps, Einstein on the Beach, which UMS’s Michael Kondziolka described on Monday as a “durational experience. If you give yourself over to it, you feel as if you’ve walked through the looking glass.”

Time, said Danny Herwitz, “is fundamental to a lot of these Renegade artists. They at once speed everything up and slow it down. They’re trying to put you in a different frame of reference.” And more provocatively: “There is a way in which [these artists] rescue one from the frame of modern life.”

May it be so.

Having decried technology, I’ll now use it, with apologies, to let you hear another panelist, musicologist Mark Clague of the UM School of Music, Theatre, and Dance, share his thoughts on time and the Renegade series.

Interested in Einstein Revival? – An Anatomy of auditioning for Einstein on the Beach

Editor’s Note: Lindsay Kesselman will sing with the Phillip Glass Ensemble for the duration of the 2012-2013 international tour of Einstein on the Beach. She’ll also be guest blogging on umsLOBBY.

I don’t know about you, but I am a fan of Philip Glass. My iPod contains everything from his symphonies to his string quartets, his film scores and solo piano music, and of course, his operas. I listen to him in the car, while I’m cooking, while I’m thinking, at the gym… sometimes you are just in a Philip Glass kind of mood. So, you can understand why I briefly stopped breathing when I received an email from a new music-singing friend last March entitled, “Interested in Einstein Revival?” I wondered how quickly I could respond without sounding desperate, but then promptly ignored this concern and wrote back, um…yes. I was interested.

As a singer, I’m usually fairly zen about auditions. Many variables are out of our control, so I try to be prepared, do my best work, but spend as little time obsessing about it as possible. I pretend I don’t care about the outcome, and tell myself that I will be successful regardless of whether or not I get the part.

The truth was, however, that this time I did care, and no amount of denial-ridden inner monologue would convince me otherwise. I sent in a resume and samples of my singing and then tried to preserve my outer calm while I waited. I didn’t have to wait long before being invited to come to New York in early May to audition at the Baryshnikov Arts Center for a chorus role.

Being part of Einstein on the Beach was beginning to become a real possibility, so I let myself get a little bit excited. I started listening to sections of the piece and I watched a wonderful documentary on the making of Einstein entitled “Einstein on the Beach: The Changing Image of Opera” which, as a side note, I would recommend highly to anyone as a fascinating introduction to the piece, or as a way to learn more for those that are already familiar with it. (All the members of my family “might” be receiving this documentary for Christmas this year.)

I also started practicing, both the piece I had decided to sing for the audition, as well as exercises I drew from Einstein. The text of the opera is comprised of numbers and solfege syllables, sometimes sung very rapidly and in constantly-changing rhythmic meters. I figured that if by some chance I was cast, I would need to start practicing immediately so I would not become hopelessly tongue-tied in rehearsals.

So, I auditioned in NYC for Lisa Bielawa, Michael Riesman, and Linda Brumbach. I was the first to sing that day (we were asked to prepare something in English), and then Michael Riesman asked me to say aloud 1 2 3 4, 1 2 3, 1 2 3 4 1 2 3, etc as quickly as possible. Aha!! My compulsive practicing of numbers had paid off. The audition was over before I knew it, and I flew home to wait again, with ever-building excitement and anticipation.

Fortune smiled, and I was invited to a callback audition three weeks later, this time to sing excerpts from Einstein, the choruses “Night Train” and “Spaceship,” as well as to complete a movement/dance audition. I arrived at the DANY Studios along with 24 other singers, all vying for 12 spots (3 of each voice type). Everyone knew each other, greeted each other warmly, with hugs, like at a big family reunion. I remember thinking about how COMPLETELY different this was from any other audition I’d ever done, and I’d hoped I’d have the opportunity to become part of this strange and wonderfully supportive community.

We were divided in half, and when it was our turn, we filed into a dance studio and faced a long table. There were many important people in the room, including a camera crew for an upcoming documentary, but I found myself staring directly at Robert Wilson. I knew what he looked like and had known he would be there, but as soon as I saw him, various highlights from his staggeringly impressive bio began running through my brain like ticker-tape, and I was stunned. I took a deep breath and decided I could be star-struck later: now was the time to focus.

We sang through the prepared sections up to tempo, I was asked to jump up to a descant line above the choir, and I started feeling pretty good. This wasn’t so bad, I thought. Then, we were divided in half again for the dance audition. Ever since the callback invitation, I tried to psych myself up for this part, but let’s be clear: I am not a dancer by any stretch of the imagination. We started off easily enough, with some focus and posture exercises. Then, Wilson asked us to cross the room, but to take at least 3 minutes to do so (very, very slowly) and, not allowing the initiation point of our movements to be seen. A fascinating challenge, one that required us to spend at least the first 30 seconds to transfer our weight to one foot.

Then, my moment of truth came. Robert Wilson left his place at the table to demonstrate a “routine” for us, which we were to instantly memorize and then re-create. As we watched, our collective adrenaline turned quickly to collective dread as the slow, stylized movement of the routine kept going… and going. Silently, I cursed my 10-year-old self for not continuing with ballet. I thought, “Well, that’s it. This was fun, but my lack of dance training will cost me this job.” No one moved a muscle when Wilson told us it was our turn. Then, slowly we forced our legs back to our positions and made the routine up the best we could, mimicking the style of the movement, if not its exact steps.

Ultimately, a miracle happened, and, a few days later, I got the invitation to join the tour. Now, months later, I am still giddy with excitement at the adventure that is about to begin. As I become familiar with each segment of my 85 page score, which will eventually expand into 4 ½ hour show, I know that in a matter of weeks, I will be singing this music in my sleep and it will become a part of who I am for the next 13 months.

My voice teacher in graduate school always told me that my path would be different, that it would probably be somewhat non-traditional, but that I would find my way. This year that path has led me to Philip Glass and Einstein on the Beach and I truly could not be more grateful.

Have a question for Lindsay, or curious about something to do with Einstein on the Beach? Use the hashtag #askeinstein on Twitter or comment below.

Einstein on the Beach: Q&A with Lindsay Kesselman

Widely credited as one of the greatest artistic achievements of the 20th century, Einstein on the Beach is a rarely performed and revolutionary work that launched director Robert Wilson and composer Philip Glass to international success when it was first produced in Avignon, France in 1976, with subsequent performances in Europe and at the Metropolitan Opera. It is still recognized as one of their greatest masterpieces. Now, nearly four decades after it was first performed and 20 years since its last production, Einstein on the Beach will be reconstructed for a major international tour, including the first North American presentations ever held outside of New York City.

Widely credited as one of the greatest artistic achievements of the 20th century, Einstein on the Beach is a rarely performed and revolutionary work that launched director Robert Wilson and composer Philip Glass to international success when it was first produced in Avignon, France in 1976, with subsequent performances in Europe and at the Metropolitan Opera. It is still recognized as one of their greatest masterpieces. Now, nearly four decades after it was first performed and 20 years since its last production, Einstein on the Beach will be reconstructed for a major international tour, including the first North American presentations ever held outside of New York City.

Prior to the production’s final technical rehearsals and world première in Montpelier, France, UMS will host the production’s creators, musicians, performers, and crew for three weeks as they reconstruct and rehearse the work for what is likely to be the final world tour designed and led by its original creative team. A rare chance to see a work of this scale in progress, these preview performances will be the only opportunity to see Einstein on the Beach in the Midwest.

Lindsay Kesselman will sing with the Phillip Glass Ensemble for the duration of the opera’s 2012-2013 international tour. She’ll also be guest blogging on umsLOBBY.

UMS: As an emerging artist, how do you approach a seminal work like Einstein on the Beach?

Lindsay Kesselman: With great humility….and tons of excitement! I remember hearing about Einstein on the Beach for the first time as a freshman in my undergraduate music history class. Even then, I remember thinking that this was my kind of opera, and exactly the sort of piece I hoped to sing one day. Now, being given the chance to participate in a re-creation of this incredible work, and in a production of this size and scope, is nothing short of thrilling.

UMS: You studied at voice at Michigan State University and have Michigan roots. Does beginning with this production in Michigan hold any special importance for you?

LK: Definitely. I received a B.M. in voice and music education from Michigan State University in 2006 and, after spending a few years away, returned to live in Ann Arbor 2 years ago. I regularly attend UMS events, and feel so fortunate that we will have the opportunity to workshop the piece and give preview performances here at the Power Center. This is a wonderfully vibrant community, filled with people who are curious and interested in a diverse array of arts, and I am so excited that they will have the chance to see this production first. For me personally, it will be wonderful to share this experience with my local family and friends, and it will be a luxury to be home during the month of January!

UMS: What are you most looking forward to during this production? What do you hope to learn from your work on this production?

LK: There are so many things to which I am looking forward…the chance to learn from the extraordinary visionaries and creators of this piece, Philip Glass, Robert Wilson and Lucinda Childs, will be a once-in-a-lifetime privilege. Learning from and growing with the remarkable members of the Philip Glass Ensemble, my fellow singers, and the entire cast and crew, will be life-changing. And certainly, having the chance to introduce this piece to a new generation of audiences across the world will be humbling and truly unforgettable.

Have a question for Lindsay, or curious about something to do with Einstein on the Beach? Use the hashtag #askeinstein on Twitter or comment below.

UMS on Film Series

Every summer, we come up with about three dozen companion-films to the UMS main-stage season. We’ve narrowed the list to five this year – two in the fall, and three in the winter. Each expands our understanding of artists and their cultures, and reveals emotions and ideas behind the creative process.

In the fall, the films highlight deep cultural expressions which grow from communities of shared heritage. In the winter, the films tie in with UMS’s PURE MICHIGAN RENEGADE series, which focuses on artistic innovation and experimentation. We’ve created a mini film festival, Pure Michigan Renegade on Film, to extend the renegade idea and explore other artists who have created new arts frontiers.

In the fall, the films highlight deep cultural expressions which grow from communities of shared heritage. In the winter, the films tie in with UMS’s PURE MICHIGAN RENEGADE series, which focuses on artistic innovation and experimentation. We’ve created a mini film festival, Pure Michigan Renegade on Film, to extend the renegade idea and explore other artists who have created new arts frontiers.

All films (except one! see below) are presented in the U-M Museum of Art Stern Auditorium (525 S. State Street) and are free and open to the public.

Pure Michigan Renegade on Film:

Helicopter String Quartet

(1995, Frank Sheffer, 81 min.)

Wednesday, March 7, 7:00 PM at the Michigan Theater (603 E. Liberty)

Tickets: $10 general admission; $7 students/seniors/UMS and Mich Theater members; $5 AAFF members

Purchase Tickets Here

The UMS Renegade on Film series culminates at the Michigan Theatre in collaboration with the Ann Arbor Film Festival (celebrating its 50th anniversary in March 2012!!). The curators at AAFF chose an amazing documentary that captures the renegade spirit and provides a fabulous lead-in to the San Francisco Symphony American Mavericks concerts. In one of the most certifiably eccentric musical events of the late 20th century, German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen designed and executed the performance: four string quartet members playing an original piece by Stockhausen in four separate helicopters, all flying simultaneously. The sound was then routed to a central location and mixed; the work premiered, in turn, at the 1995 Holland Festival. Frank Scheffer’s film Helicopter String Quartet depicts the behind-the-scenes preparations for this event; Scheffer also conducts and films an extended conversation with Stockhausen in which the creator discusses the conception and execution of his composition and then breaks it down analytically. Featuring music by Karlheinz Stockhausen, performed by the Arditti String Quartet. Co-presented with the Ann Arbor Film Festival in partnership with the Michigan Theater, in collaboration with the U-M Museum of Art.

Past Films…

Fauborg Tremé: The Untold Story of Black New Orleans

(2008, Dawn Logsdon, 69 min.)

Tuesday, October 11, 7 pm

Connected with UMS’s presentation of A Night in Tremé: the Musical Majesty of New Orleans, this documentary follows Lolis Eric Elie, a New Orleans newspaperman on a tour of his city, a tour that becomes a reflection on the relevance of history, folded into a love letter to the storied New Orleans neighborhood, Faubourg Tremé. Arguably the oldest black neighborhood in America and the birthplace of jazz, Faubourg Tremé was home to the largest community of free black people in the Deep South during slavery, and it was also a hotbed of political ferment. In Faubourg Tremé, black and white, free and enslaved, rich and poor co-habitated, collaborated, and clashed to create America’s first Civil Rights movement and a unique American culture. Wynton Marsalis is the executive producer of the film, which also features an original jazz score by Derrick Hodge. Introducing the film is U-M American Culture faculty member Bruce Conforth, whom some may remember from last season’s series on American Roots music.

AnDa Union: From the Steppes to the City (with director Q&A)

(2011, Sophie Lascelles and Tim Pearce)

Tuesday, November 8, 7 pm

Before AnDa Union takes the stage at Hill Auditorium, filmmakers Sophie Lascelles and Tim Pearce will screen their new documentary, which follows the group of 14 musicians who all hail from the Xilingol Grassland area of Inner Mongolia. The film premieres at the London Film Festival on October 13, and Ann Arbor will be one of the first to screen it after its debut. AnDa Union is part of a musical movement that is finding inspiration in old and forgotten folk music from the nomadic herdsman cultures of Inner and Outer Mongolia, drawing on a repertoire of music that all but disappeared during China’s recent tumultuous past. Tim and Sophie will be here in Ann Arbor to introduce the film, and take audience questions after the screening.

Absolute Wilson

(2006, Katharina Otto-Bernstein, 105 min.)

Tuesday, January 10, 7 pm

Absolute Wilson chronicles the epic life, times, and creative genius of theater director Robert Wilson. More than a biography, the film is an exhilarating exploration of the transformative power of creativity – and an inspiring tale of a boy who grew up as an outsider in the American South only to become a fearless artist with a profoundly original perspective on the world. The narrative reveals the deep connections between Wilson’s childhood experiences and the haunting beauty of his monumental works, which include the theatrical sensations “Deafman Glance,” “Einstein on the Beach” and “The CIVIL WarS.”

The Legend of Leigh Bowery (with director Q&A)

(2002, Charles Atlas, 60 min.)

Monday, February 13, 7 pm

Renegade filmmaker Charles Atlas (who worked extensively with the late choreographer Merce Cunningham) introduces his 2002 documentary The Legend of Leigh Bowery. Artist/designer/performer/provocateur Leigh Bowery designed costumes and performed with the enfant terrible of British dance Michael Clark, designed one-of-a-kind outrageous costumes and creations for himself, ran one of the most outrageous clubs of the 1980s London club scene (later immortalized in Boy George’s Broadway musical “Taboo”), and was the muse of the great British painter Lucian Freud. The film includes interviews with Damien Hirst, Bella Freud, Cerith Wyn Evans, Boy George, and his widow Nicola Bowery. Charles Atlas will participate in audience Q&A immediately following the film. This film is co-presented with the U-M Institute for the Humanities which hosts Charles Atlas’s video installation “Joints Array” in February 2012.

Renegade Series

Renegade

The focus on “renegades” in the 11/12 season examines thought-leaders and game-changers in the performing arts and encompasses performances that are part of the UMS International Theater Series, Choral Union Series, Divine Voices, Dance Series, and the Chamber Arts Series. Performances under this umbrella will take place in a ten-week period from January – March 2012 and include:

- Philip Glass & Robert Wilson’s Einstein on the Beach

- From the Canyons to the Stars, performed by the Hamburg State Symphony

- The Tallis Scholars, performing Tenebrae Responses by renegade Italian Renaissance composer Carlos Gesualdo

- Random Dance, a company started by Wayne McGregor , the resident choreographer at The Royal Ballet, Covent Garden, whose groundbreaking collaborations across dance, film, music, visual art, and science is evident in the company’s presentation of FAR

- Robert Lepage’s The Andersen Project, a solo performance created by this Canadian theater visionary that explores sexual identity, unfulfilled fantasies, and the thirst for recognition and fame through Hans Christian Andersen’s timeless fables

- The four concerts of the San Francisco Symphony’s American Mavericks festival. In addition to the three orchestral concerts noted in the Choral Union Series, members of the San Francisco Symphony will present a chamber music concert to close both the American Mavericks festival and the UMS focus on Renegades.

Subscription packages go on sale to the general public on Monday, May 9, and will be available through Friday, September 17. Current subscribers will receive renewal packets in early May and may renew their series upon receipt of the packet. Tickets to individual events will go on sale to the general public on Monday, August 22 (via www.ums.org) and Wednesday, August 24 (in person and by phone). Not sure if you’re on our mailing list? Click here to update your mailing address to be sure you’ll receive a brochure.

Return to the complete chronological list.