Community Spotlight: U-M Piano Professor Arthur Greene

Editor’s note: Isabel Park is a regular contributor to UMS Lobby and an undergraduate pianist in the U-M School of Music, Theatre & Dance. Isabel explores connections between the UMS season and student life.

Photo: Pianist Andras Schiff performs in Ann Arbor February 16-20, 2016. Photo by Nadia Romanini.

This winter, master pianist Sir András Schiff visits Ann Arbor for three concerts exploring the “The Last Sonatas,” later-life sonatas, of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert. He says of the sonata, that it is “one of the greatest inventions in Western music, and it is inexhaustible.”

We often view the musicians on stage as learning students or a developing performers, but, perhaps more rarely, do we think of the musicians as a teachers. Teachers can play a significant role in shaping a student’s musical style and artistic ideas. To gain some insight into the perspective of teachers and find out more about what it’s like to help younger musicians grow into independent artists, I talked to my own teacher at U-M, Arthur Greene.

Isabel Park: We’ve worked on the Beethoven Op. 109 together. Can you give an overview of the process of teaching a piece from the teacher’s perspective?

Arthur Greene: There are two sides to teaching. One is communicating and developing a conception of the work – to put it in an overly simplistic way, what the work means. The other is responding to the particular student’s way of playing and learning. With a late Beethoven sonata, our work is weighted towards the meaning of the music, because it is so particular, dense, and at first enigmatic. As far as the student’s playing, I always try to combine technical suggestions with musical ideas, based on what is working or what is not working for the student.

IP: I know this is a difficult question, but when is a piece “good enough” or ready to be performed?

AG: We had a visiting “great artist” when I was first teaching at Michigan, Eugene Istomin, to teach every few weeks. He said that in his life there were never any performances he was happy with, and usually he was very distressed after playing, because they fell so far short of perfection. I don’t think like that. When the music feels part of you, well memorized, with technical issues working 90% of the time, and if you feel you have something to say with the piece, it is ready to play.

IP: Is there anything that, say, can’t be taught to a student – or anything that you consider to be the responsibility of the student?

AG: Almost everything is the responsibility of the student. Most great teachers, such as Theodore Leschetizky, would have been unknown if they didn’t have students the caliber of Ignaz Friedman and Artur Schnabel. Teachers can inspire and guide, but the student should not rely on the teacher ultimately, or else he or she will never be an artist.

IP: What kind of a role do these classical sonatas play in the piano/classical music repertoire in general and in the repertoire of a pianist?

AG: Beethoven, Mozart, and Haydn represent the summit of the tonal system, and their sonatas are simply great music, so I can’t imagine being a pianist without playing them.

IP: For this program, Schiff is exploring the “last” sonatas of four master composers and the ways in which later-life creativity or near-death creativity was expressed for each of them. What’s your take on this programmatic structure, especially given that your work focuses on nurturing the emerging creativity of student pianists?

AG: Most composers whose works I know well develop a more subtle, complex, and personal style in their later works – Chopin, Beethoven, and Mozart for example. These are the pieces I am personally most drawn too, and I am not surprised that Schiff is as well.

IP: It’s often said that one shouldn’t say the masters until one as older (this is said humorously). What do you think about this idea?

AG: Kids might not have the last word on late Beethoven, but I’ve heard horrible performances of mature works by mature pianists as well. I like the idea of a work maturing in one’s soul for many years. Also, the idea that one must learn all the patterns of earlier music of a composer before tackling the later works is dangerous, because it fosters a paint-by-numbers way of playing. It is better to consider each pattern, phrase, and piece on its own, rather than as a meme. Overly patterned playing, and the desire to find the correct way to play something, are the reasons piano playing has become so dull.

IP: What are your favorite works to introduce to students?

AG: Chopin mazurkas. They are fascinating emotionally and rhythmically, and most of them are rarely played.

Thinking about the teaching embedded in music adds another dimension of complexity and inspiration to a performance. I’m excited to listen to pianist András Schiff’s programs with an eye for these complexities.

Sir András Schiff performs three concerts in Ann Arbor February 16-20, 2016.

Student Spotlight: Jiakung Feng, U-M student pianist

Editor’s note: Isabel Park is a regular contributor to UMS Lobby and an undergraduate pianist in the U-M School of Music, Theatre & Dance. Isabel explores connections between the UMS season and student life.

Photo: Pianist Igor Levit. By Felix Broede.

Pianist Igor Levit makes his UMS debut with a program of Beethoven, Shubert, Prokofiev, and Bach on February 6, 2016. Despite his demanding program, Levit is a relatively younger, up and coming pianist.

Much takes place behind the scenes when preparing a piece for performance, and often the audience is unaware of these aspects when listening to a performance. To get a deeper understanding of being a learner musician rather than simply a performer, I reached out to Jiakung Feng, a fellow pianist who has worked on some of the pieces on Mr. Levit’s program.

Photo: Jiakung Feng

Isabel Park: Prokofiev’s Sonata No. 7 in B-flat Major is on Mr. Levit’s program for UMS. Why did you want to learn this Prokofiev piece?

Jiakung Feng: Well, I’ve always liked Prokofiev, and I’ve played some of his other works, such as Diabolical Suggestions and The Love for Three Oranges. I also played the third sonata and wanted to play one of his later ones, so I asked my teacher and he suggested the seventh one.

IP: This is undoubtedly a difficult piece to learn. How you did you approach learning it?

JK: I found the whole sonata to be challenging to understand from a musical sense and difficult to perform from a technical perspective as well. The piece is also extremely dissonant, so just from a learning perspective, it took longer for me to actually learn all the harmonies and notes. I also listened to recordings online to listen how the great pianists interpreted this work. I especially admire Richter’s rendition.

IP: Was there a section that was memorably difficult? If so, could you describe the ways in which it was challenging? How does working through these challenges fit in with your life as a musician, and also your life outside of music?

JK: I found the sections in the first movement with jumping and cascading octaves and chords difficult to learn and play accurately. There were also uncomfortable stretches (9ths) that were taxing on my hands physically. I practiced these parts by focusing on voicing to the outsides and chunking the runs into smaller bits and then joining them together after I could play the smaller sections accurately.

I think learning a piece like this teaches one how to work through a problem, which is a good skill to have for anything. Learning something like this comes with discipline and determination.

IP: Does learning new music get easier as you learn more pieces?

JK: I think it helps to have a wide range of repertoire by a specific composer because one can begin to understand the tendencies and styles of each composer, which makes learning works by the same composer easier.

For example, if you’ve played many of the Chopin Nocturnes, you might be better accustomed to adjusting the voicing, sound, and texture in a particular way that fits that set of pieces.

IP: What sets apart the first time you perform a newly learned piece? In other words, are there any unique challenges or aspects of the experience?

JK: There’s the nerves. Even if one plays for small groups of friends as a form of practicing for performance in front of a bigger audience, there’s something different about being on stage. I becomes hypersensitive, and sometimes I might hear things that I didn’t hear while practicing. It’s hard to have continuous concentration, and in the presence of a larger audience, there’s a special atmosphere and a connection to create as well.

Photo: Igor Levit. Courtesy of the artist.

IP: Igor Levit, who’ll perform this piece with UMS, is a younger, emerging pianist (this will be his first U.S. recital tour). You are also a younger student of piano. Do you feel that where you are in your career or journey has an impact on how you study and perform?

JK: Ultimately, yes. Being a pianist in school is a lot more routine than being an independent artist. Every semester, we’re required to perform for a jury with with general guidelines, for example. As a result, there’s a specific timeline to how we prepare and goals to ensure that all the requirements are met.

Also, as students, we’re inevitably influenced a lot by our teachers’ interpretive choices. They serve as mentors and usually have direct experience with pieces that we’re learning for the first time, so in my case, my teacher’s musical ideas guide my playing quite a bit.

To me, it’s exciting to think of performance as not only a presentation but also a learning experience for the musician. I’m excited to attend pianist Igor Levit’s debut recital at UMS to witness this part of career as a pianist.

Protected: Student Spotlight: U-M student Ce Sun, concerto competition winner

Student Spotlight: U-M First-year Student Isabel Park Sets Out to Explore Piano

Editor’s Note: Isabel Park is a first-year student at the University of Michigan, where she’s studying piano at the School of Music, Theatre, and Dance. This year, she’ll explore piano throughout our 2015 season, attending performances by pianist Yuja Wang and violinist Leonidas Kavakos (11/23), Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra with pianist Hélène Grimaud (2/19), Academy of St. Martin in the Fields with pianist Jeremy Denk (3/25), and pianist Richard Goode (4/26).

In the essay below, she explores her relationship with the piano. Follow her adventures and thoughts on UMS Lobby.

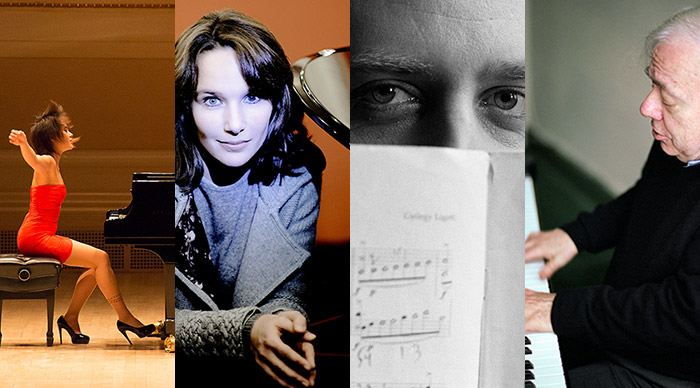

From left to right, pianists Yuja Wang, Hélène Grimaud, Jeremy Denk, and Richard Goode, all part of the 2014-2015 UMS season. Photos by Ian Douglas, Mat Hennek, and Michael Wilson.

The complexity of piano playing is astounding. Rarely do other tasks demand the intensity of full-body engagement that the piano does. Given its intricacy, piano playing can be crudely divided into technical and mental aspects; not surprisingly, a successful piano performance ultimately relies on the pianist’s adeptness in both areas, and the relative importance of each with respect to the other remains a highly disputed topic amongst pianists.

Is technique vital?

However, the relationship between a pianist’s musicianship and technical capacity is not so mutually complementary as it is often thought to be, but rather one-sidedly supplementary. Improving an aspect of one’s playing does not necessarily do the same for the other. Instead, technique supplements ability to express with a boundless sense of musicianship and musicality. Solid technique is not only a desirable, but vital to superlative piano playing that encompasses both outstanding technicality and depth of expression.

It is natural to conclude that the technical facet of piano performance is easier to approach— not necessarily easy— in the sense that improving one’s technique can be done methodically. While musicianship primarily concerns the mind, a highly equivocal part to deal with, technique mainly deals with the pianist’s physical body. The pianist can pinpoint and address specific parts of the body to enhance corresponding areas of technical facility. Not only that, technical development is easier to facilitate than musical growth because it can be measured by a universal numeric system in the form of tempi and durations, which enable objective comparisons and indications of improvement.

A unique body engagement

Yes, piano playing demands an exceptional degree of body engagement. Not only are we exercising hand-eye coordination of infinitesimal detail and precision, but the feet are also working their own set of motion. Even more uniquely, playing piano requires an unusual amount of bodily symmetry. A string player holds and draws the bow with her right hand while the left hand takes charge of fingering; similarly, a brass player manages valves with the left hand while the right hand provides support. On the piano, the hands of a pianist cover the very same keys, able even to crossover, to exchange control over different ranges, which truly gives a pianist’s hands symmetric action and equal opportunity. The bodily symmetry of piano playing also applies to the feet as they share access to the three pedals— one foot per outer pedal and a third equally distanced between the other two.

This quality of piano playing has a rather burdening implication: a pianist’s left and right hands and feet must be perfectly equivalent in terms of technical dexterity. The solution seems unrealistically simple— train each half of the body identically. Unfortunately, this proves problematic because most of us are born with dominant hands and legs that naturally possess a higher level of technical proficiency. The pianist is left with a challenge, alongside many others, of developing an artificial ambidexterity in order to master the symmetric art of piano playing.

Interestingly, piano playing is also set apart from the playing of other instruments by a factor of non-symmetry. This happens in two different, but related, respects— clefs and voices. Aside from other keyboard-natured instruments ( organ, harpsichord), the piano is the only instrument that requires the player to simultaneously read and internalize two different clefs.

A polyphonic ability

But above all, the pinnacle of piano playing and its grandeur is derived from the pianist’s polyphonic ability. Once the pianist considers the multitude of voices that he or she produces, the asymmetric factor becomes intensely complex. Although the prime examples of polyphonic music are the Bach fugues that showcase up to five voices at a time, essentially all piano music encompasses varying degrees of polyphony.

The abundance of notes is not an arbitrary flux, but rather multiple voices concurrently played. The pianist’s responsibility is to prioritize: which is the melody and which are accompaniment? He or she must voice accordingly in order to clearly and efficiently deliver the melody. The greater individuality the fingers possess, the easier this is, since the hand playing the melody is often playing an accompanying voice as well.

But the true challenge of playing polyphonic music extends beyond our fingers. The pianist’s brain must be able to process what is comparable to multiple languages to deliver a cohesive, collective body of sound. This also challenges the ears. The problem usually arises at the point of memorization. At this point, the pianist might be so accustomed to knowing the piece as the collective body of sound that she strives to produce; however, complete memory requires a detailed knowledge of each and every line of sound within the piece as well.

Being on stage

Finally, no matter how prepared, many external factors tamper with a performer’s mental condition when on stage. Performance anxiety almost always results in hyper-awareness, oversensitivity to one’s surroundings and one’s own playing, even. In many cases, the performer becomes so aware of miniscule details that perception is distorted. She could hear things within the piece that seem new or even forget the first note.

In any case, the goal is to replicate this hyper awareness in the practice room so that one simply cannot be ove-aware on stage. To combat this, isolate each sense— hearing, sight, and touch— and focus entirely on it. This level of focus is extremely difficult to maintain for prolonged periods, so dividing the movement or piece into compact sections is more productive.

Why see performances?

But given the endless ways to learn through practice and internalizing, nothing can directly replace the inspiration and teaching that transpires during a live performance. That’s why I am particularly excited to see Yuja Wang, Hélène Grimaud, Jeremy Denk, and Richard Goode live this season.

Yuja Wang has visited my hometown, San Francisco, quite a few times, and I’ve missed all of those performances. The endless mentions of her amazing technical facility and her controversial outfits have raised my curiosity as a fellow female pianist. As for Hélène Grimaud, I first heard of her through a pianist friend who raved about her live performances. Not one to praise easily, my friend has inspired me to find out first-hand what’s made her playing so extraordinary. I read Jeremy Denk‘s blog extensively, and love his very deep sense of understanding of music, something I consider quite important to good performance. On the contrary, Richard Goode remains quite a mystery to me; I know that he is part of the piano faculty at Mannes and have heard highly positive reviews of his performances. I cannot wait to see him perform live to discover what it is about him that captures those around him.

Interested in more? Follow Isabel’s thoughts and adventures here on UMS Lobby. She’ll participate in our “People are Talking!” conversations after each performance she attends.