Ann Arbor History: Chick Corea and Herbie Hancock in Hill Auditorium

We are devastated that Chick Corea, one of the most prolific jazz greats of our time, passed away on Tuesday, February 9, 2021. UMS first presented Chick in 1994 at the Power Center, and most recently in 2019 as part of his ‘Trilogy’ tour with Christian McBride and Brian Blade. In addition to his seven UMS appearances spanning nearly three decades, Chick’s remarkable discography of nearly 90 albums includes a special connection to Ann Arbor and Hill Auditorium.

Hill Auditorium stage: April 16, 2015

Photo by Mark Jacobson, UMS

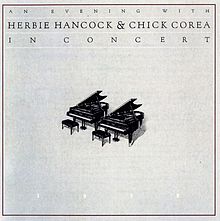

On Thursday, April 16, 2015, UMS presented An Evening with Chick Corea and Herbie Hancock at Hill Auditorium. Two “nested” grand pianos with their lids removed adorned the stage at Hill Auditorium as a sold-out audience eagerly anticipated the forthcoming music. Some audience members in attendance may have remembered that this was not the first time that Chick and Herbie appeared alone together on the Hill stage; one would have to dive back to a winter night in February 1978 that ultimately resulted in side four of the now-classic album, An Evening with Herbie Hancock & Chick Corea: In Concert.

Please enjoy revisiting this musical gem of Ann Arbor history:

In 1978, jazz legends Chick Corea and Herbie Hancock were brought to Ann Arbor by Eclipse Jazz, a University of Michigan student group that existed from 1975 to 1987. Eclipse brought world-class jazz musicians to Ann Arbor for concerts, lectures, and workshops, and presented such greats as Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Charles Mingus, Dexter Gordon, Sun Ra, Oscar Peterson, Mary Lou Williams, Sonny Stitt and Rahsaan Roland Kirk.

We asked Lee Berry, former director of Eclipse Jazz and current Chief Development Officer at the Michigan Theater, to tell us all about the epic concert.

Hancock and Corea’s first show together at Hill Auditorium was scheduled for January 26, 1978, a date that might ring some bells for those who were university students during this time, because it was also known as the Great Blizzard of 1978. The University shut down due to snow that day.

Says Berry, “I think we learned that school was being cancelled, and then they called and said that [Herbie and Chick] couldn’t get out of New York.” The only reschedule date that worked for the musicians, Eclipse, and Hill Auditorium was February 26, 1978. The sold-out performance was to occur that day during the day time. Still, most of the 4177 ticket holders showed up, and, as Berry puts it, “it was a beautiful, beautiful show.”

The encore of that Hill Auditorium performance is side four of An Evening with Herbie Hancock & Chick Corea: In Concert, an album that Berry describes as a departure from the electric keyboard and fusion style of jazz that Corea and Hancock were known for before that album, and as a return to the acoustic piano and older, more collaborative style of playing that is the kind of jazz that has survived and is still thriving today. The recording, featuring two jazz greats changing the course of jazz’s future, was a moment in history. As Berry remembers, “Not too long after is when Wynton [Marsalis] came out, maybe ’81, and it was like old-school was back. This was kind of like a link between those two periods.”

The encore of that Hill Auditorium performance is side four of An Evening with Herbie Hancock & Chick Corea: In Concert, an album that Berry describes as a departure from the electric keyboard and fusion style of jazz that Corea and Hancock were known for before that album, and as a return to the acoustic piano and older, more collaborative style of playing that is the kind of jazz that has survived and is still thriving today. The recording, featuring two jazz greats changing the course of jazz’s future, was a moment in history. As Berry remembers, “Not too long after is when Wynton [Marsalis] came out, maybe ’81, and it was like old-school was back. This was kind of like a link between those two periods.”

Stream the full album, including “Maiden Voyage” and “La Fiesta” recorded in Hill Auditorium, on Apple Music or Spotify.

For further reading:

Herbie Hancock on Chick Corea: ‘He Always Wanted to Share Whatever He Had’ (Rolling Stone)

Updated 2/19/2021

The Great Pipe Organ

From April to October 1893, the World’s Columbian Exposition—called the “White City” for its alabaster architecture and its nightly illumination by millions of electric lights—drew the rapt attention of much of the world. Some 27 million people traveled to Chicago’s Jackson Park to see it. Of these, several hundred thousand entered the 10,000-seat Festival Hall to hear what was widely regarded as one of the greatest musical instruments—and certainly one of the largest—ever constructed.

It was a 3,901-pipe organ, 34 feet wide by 25 feet deep, 38 feet tall at its highest point, manufactured by the Farrand & Votey Company of Detroit to specifications drawn by the eminent organist Clarence Eddy of Chicago, incorporating features invented by Frank Roosevelt of New York City, first cousin to Theodore Roosevelt. It was one of the first great organs to rely on electrical connections from its keys to its pipes, which ranged from the size of soda straws to the size of tree trunks. Together they could replicate the sounds of a vast symphony orchestra.

Photo: The Ferris Wheel at the World’s Columbian Exposition

Over the six months of the fair, “the most eminent of contemporary organists” entertained crowds at 62 recitals in all. On the fair’s last day, Clarence Eddy himself wrote of the organ that “musically, it is worthy of rank among the few great organs of the world, while from a technical standpoint it occupies a supreme position.

Later the following winter, long after the last fair-goers had gone home, workmen entered Festival Hall, took the organ apart, packed the pieces in crates, and loaded the crates on rail cars bound for Cincinnati. After a few months in storage, the parts were packed up again and shipped to Ann Arbor.

In the era before radio and high-quality phonographs, when symphony orchestras were relatively rare, Americans of the late 19th and early 20th centuries listened to great pipe organs with a mixture of technological awe, local pride, and aesthetic rapture. Cities competed to buy the biggest and best. The steel baron Andrew Carnegie, famous as the benefactor of city libraries, also gave millions for municipal organs. Community fund drives were organized to buy instruments made by the most prestigious manufacturers and played by the most famous musicians. When the preeminent organmaker Ernest Skinner installed a new instrument in Cleveland in 1922—”The Finest Musical Instrument ever built by man,” ads said—a crowd of some 20,000 swept past police to squeeze into an arena built to hold only 13,000. (The show went on as planned.) The richest Americans had genuine pipe organs installed in their homes, and a new industry grew up to provide humbler home organs for the middle class.

For many years before the Columbian Exposition of 1893, Henry Simmons Frieze, professor of Latin and three times the University’s interim president, had argued for the installation of a first-class organ on the campus.

Frieze was the progenitor of Michigan’s musical tradition. A fine amateur organist, pianist and conductor, he launched student bands and choral clubs and introduced organ music to the daily chapel services. He persuaded the Regents to appoint the first professor of music. He was the principal founder of the University Musical Society (UMS), which was to make Ann Arbor a national center of fine music.

Frieze believed the shared experience of music was essential to a liberal education and to community life, and students agreed. In 1874, student journalists proposed a scheme by which a fine organ could pay for itself in six months through the sale of ten-cent tickets to all those who couldn’t afford a piano in their homes.

“Music,” they wrote, “good refining music, at a low price, is what the thousand homeless students and the poor people of this city are craving, and they will gratefully acknowledge as a benefactor whoever will furnish it to them.”

No benefactor stepped forward, and Frieze died in 1889, but his campaign for an organ soon was taken up by the University Musical Society. It was led by Professor A.A. Stanley, first dean of the new School of Music (and co-composer of the beloved U-M anthem Laudes Atque Carmina), and Francis W. Kelsey, professor of Latin (and namesake of the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology). Both were indefatigable organizers. First they raised money from townspeople to construct a new building for UMS. Then the two professors set their sights on Chicago, where, in the wake of the Columbian Exposition, the great Farrand & Votey organ was for sale.

The country was in the midst of a financial depression. Farrand & Votey had rented the organ to the Exposition for $10,000. Now they were asking a purchase price of $15,000—nearly $400,000 in 2010 currency. The University was in no position to pay such a sum for a musical instrument, however grand.

So Professors Kelsey and Stanley designed a public appeal. Major donations came from U-M alumni and music enthusiasts in Ann Arbor, Detroit, Grand Rapids, Chicago, and New York. More was raised through the sale of tickets to a grand inaugural concert—$5 to cover the cost of the concert plus train fare from anywhere in the state.

It was enough. For five months, workmen reassembled the organ in the auditorium of University Hall, then the central building of the campus, fronting State Street just east of where Angell Hall stands now.

On December 14, 1894, before a full house, Professor Kelsey declared that the organ was to be named in honor of Henry Simmons Frieze. Then he formally turned it over to the Board of Regents.

“Its splendid harmonies will ever please,” Kelsey said, “but those keys, touched by master hands, will speak a deeper message than that merely of beauty, of aesthetic pleasure. This organ will become an educational force in the hearts and lives of our young people…. May it touch and thrill their inmost natures…lifting them away from that which is mean and trivial into the clear shining of the ideal.”

* * *

Photo: Hill Auditorium stage in 1913.

The organ was played in University Hall for nearly 20 years, including at twice-a-week vesper services. In 1913, it was once again disassembled, moved a couple hundred yards to the north, then re-installed—with $16,000 worth of additions—as the centerpiece of the new Hill Auditorium. (It took an estimated 100 wagon trips to roll the components over to the new site.) It was played at countless performances, including regular “Twilight Recitals” for students enjoying late-afternoon respites after class.

In 1928 most of the organ’s parts were replaced in a major overhaul by Ernest Skinner—the designer whose installation in Cleveland had caused a near-riot six years earlier—but the new instrument remained the Frieze Memorial Organ. Further reconstructions and additions followed in 1955, 1985, 1990 (after extensive damage from a roof leak) and 1995, when digital circuitry and solid-state components were added.

According to James Kibbie, U-M professor of organ, the Frieze instrument now contains “120 ranks [of pipes] plus an additional 4 ranks in the Echo division above the central skylight, totaling 7,599 speaking pipes.” Of those 120 ranks, a dozen ranks remain from those that were manufactured at Farrand & Votey’s factory in Detroit—the last original components of the Frieze Memorial Organ.

Celebrate this Valentine’s Day on Sunday, February 14, 2016 at 4 pm with the UMS Choral Union Concert: Love is Strong as Death.

(Sources include James O. Wilkes, Pipe Organs of Ann Arbor (1995); James Kibbie, The Hill Auditorium Organ; James B. Angell, “A Memorial on the Life and Services of Henry Simmons Frieze” (1890); Frank D. Abbott, ed., “Musical Instruments at the World’s Columbian Exposition” (1895); Craig R. Whitney, “All the Stops: The Glorious Pipe Organ and Its American Masters” (2003), Charles H. Gray, “Musical Interests at the University of Michigan,” American University Magazine (1897); and “The U of M Organ,” The Song Journal (1895).)

This article appears courtesy of the online alumni magazine Michigan Today. It was published on May 12, 2010.

Why Audra McDonald Loves Ann Arbor

When singer Audra McDonald performed in Ann Arbor in 2011, we asked her what she loves about Ann Arbor audiences. She returns on September 17, 2015.

Our Very Own Audra McDonald Round Up

Audra McDonald. Photo by Andrew Eccles.

We can’t wait for the return of six-time Tony Award winner Audra McDonald. She’ll perform at Hill Auditorium on September 17, 2015.

UMS has had the honor of presenting Audra McDonald a few times over the course of recent year, and the singer has been very generous with her time with students, staff, and more.

Here’s a round up of our favorite Audra McDonald moments in the past few years.

1. The one where she raves about Ann Arbor audiences:

2. The one where she sings a birthday song for Hill Auditorium:

3. The one where she answers questions from University of Michigan students:

4. And of course, the one where we got to ask a few questions.

What are your favorite Audra McDonald moments?

U-M Swimming & Diving Team Meets UMS

On a summery July 2015 day, the University of Michigan Swimming & Diving team spent the day with UMS, getting an up close look at Burton Tower and historic Hill Auditorium, and learning more about performance. Go blue and watch the highlights of the day:

Interested in more? Read this great re-cap of the day.

Michael Tilson Thomas at 1988 UMS May Festival

We’re getting ready for another visit from San Francisco Symphony on November 13 and 14, 2014. This visit celebrates the 70th birthday of music director Michael Tilson Thomas, and we wanted to share two archival photos from another performance featuring conductor Michael Tilson Thomas, the 1988 UMS May Festival.

In this photo, the Pittsburgh Symphony performs at 1988 May Festival with Michael Tilson Thomas conducting.

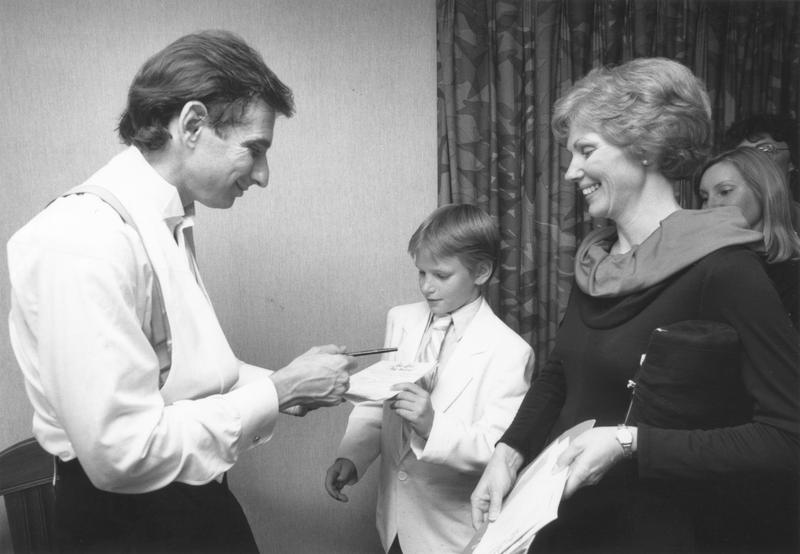

Michael Tilson Thomas signs autographs backstage in Hill Auditorium.

To learn more about the May Festival’s one-hundred year history, watch “A Space for Music, A Seat for Everyone,” our feature documentary about Hill Auditorium.

Interested in more from our archives? Check out our digital archives at umsrewind.org.

UMS Documentary Wins EMMY Award

We are honored to report that our “A Space for Music, A Seat for Everyone” documentary has just won the ‘Best Historical Documentary’ EMMY at the Michigan EMMY award! Thank you to everyone who worked on the film and congratulations! Our own Sara Billmann holds the award in the photo above.

Watch the film in full on ums.org.

This Day in UMS: Twentieth Annual UMS May Festival

Editor’s Note: “This day in UMS History” is an occasional series of vignettes drawn from UMS’s historical archive. If you have a personal story or particular memory from attending the performance featured here, we’d love to hear from you in the comments.

May 14-17, 1913: Twentieth Annual UMS May Festival

Featuring five concerts over five evenings, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, UMS Choral Union, and the Children’s Choir were featured on the Twentieth Annual May Festival, the opening series of concerts at Hill Auditorium. The opening concert featured works by Wagner, Beethoven, A.A. Stanley, and Brahms.

Hill Auditorium celebrated its one hundredth birthday on May 14, 2013. If you’d like to learn more about our history with the storied venue, watch our documentary A Space for Music, A Seat for Everyone.

This Day in UMS: Jascha Heifetz

Editor’s Note: “This day in UMS History” is an occasional series of vignettes drawn from UMS’s historical archive. If you have a personal story or particular memory from attending the performance featured here, we’d love to hear from you in the comments.

March 14, 1951: Jascha Heifetz in Hill Auditorium

Photo: Charles and Alva Gordon Sink.

We love this photo of first UMS president Charles Sink and his wife Alva Gordon Sink and a promotional sandwich board featuring Russian violinist Jascha Heifetz’s 1951 performance in Ann Arbor.

He first performed in Ann Arbor in 1919, at age 18. He was already a sensation. He was also, as Charles Sink Remembered, “a normal boy interested in everything before him.” Touring the campus before the concert Heifetz wanted to see the medical school, asking, “Do they cut up bodies, and can one see them?” Sink arranged to take him to the anatomy lab, where Heifetz watched intently, asking many questions. To Sink’s relief, the medical students “refrained from their usual practice of dropping stray toes” or other body parts into the pockets of an unwary visitor.

Heifetz returned for many concerts and he always mentioned his Michigan “medical course.”

This Day in UMS: Vladimir Horowitz

Editor’s Note: “This day in UMS History” is an occasional series of vignettes drawn from UMS’s historical archive. If you have a personal story or particular memory from attending the performance featured here, we’d love to hear from you in the comments.

January 31, 1930: Vladimir Horowitz in Hill Auditorium

Photos: (Left) 1930 advertisement in the Ann Arbor News (Ann Arbor News Ann Archives, Arbor District Library). (Right) Program from 1978 performance.

The great Russian pianist Vladimir Horowitz first performed in Ann Arbor on January 31, 1930, and then on another 8 occasions before 1953, when he began his long “intermission” from the concert stage. For music lovers, those years only enhanced his legend, and his return to stage in the 1970s caused a sensation.

For the inaugural concert of the hundredth season of UMS concerts in 1978, no artist could have been more fitting. Adding to the centennial pride of the local audience, the pianist was celebrating his fiftieth anniversary of his own American debut. This 1978 performance, before an enraptured audience, featured a program of works of Chopin, Rachmaninoff, and an enraptured audience found it hard to let Horowitz go, calling him back for four encores.

‘Tis the Season: Your Messiah Memories

An annual tradition since 1879, UMS’s presentation of Handel’s Messiah has become a “signature” Ann Arbor experience. We’re so grateful for the participation of the community in this event year-after-year, and we hope you’ll share with us some of your favorite Messiah memories: how many years you’ve attended, why you look forward to Messiah every year, what makes this event special to you.

Share your memories with us in the comments below, or on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram with hashtag #umslobby. Photos welcome!

Over the year’s we’ve also collected video memories. Here are a few audience reactions to last year’s performances.

These two are getting a bit of off-camera direction…

Graduated U-M in 1978, and attended ever since…

Snow storm strikes in the middle of Messiah…

Whole family in the video booth…

And here are some of our favorites from throughout our history.

Jerry Blackstone, director of UMS Chormal Union and long-time Messiah conductor, on forgetting his jacket on the day of a Messiah performance.

Father Timothy Dombrowski, choral union member for over forty years, remembers “The Bat out of Hill.”

Megan Sajewski, U-M alumni and resident of Martha Cook dormitory, talks about co-chairing the annual Martha Cook Messiah Dinner.

Last updated 4/29/2016.

This Day in UMS: Enrico Caruso

Editor’s Note: “This day in UMS History” is an occasional series of vignettes drawn from UMS’s historical archive. If you have a personal story or particular memory from attending the performance featured here, we’d love to hear from you in the comments.

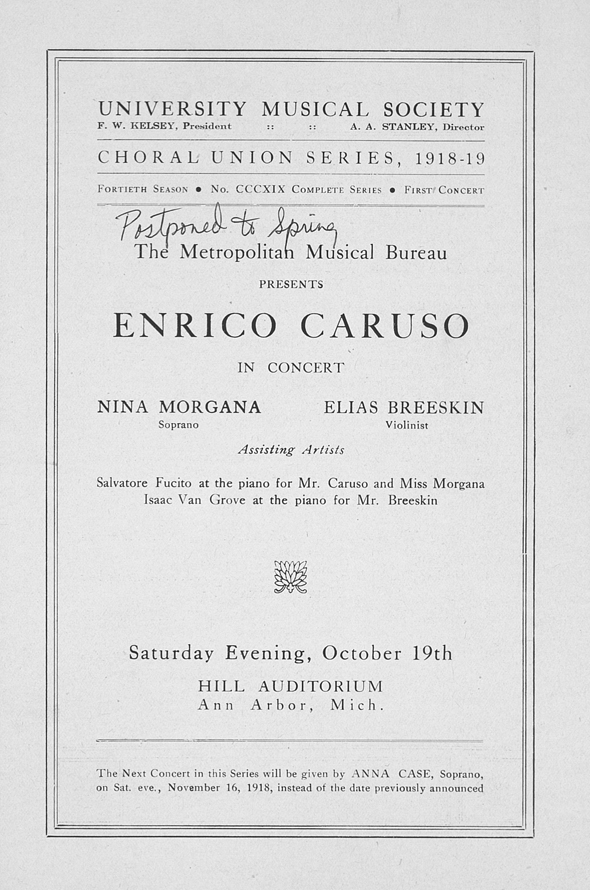

October 19, 1918: Enrico Caruso with Nina Morgana, soprano, and Elias Breeskin, violinist

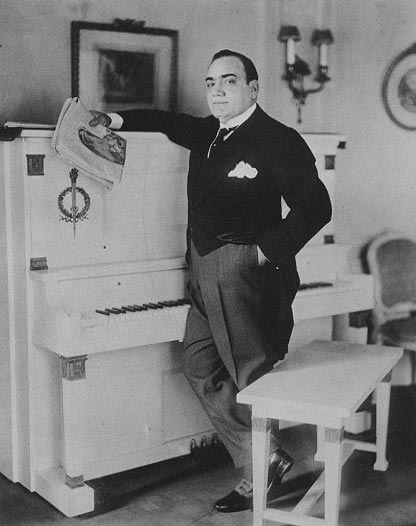

Photo: (Left) Enrico Caruso with his piano. (Right) UMS concert program.

Near the end of his 25-year career, Italian tenor Enrico Caruso was scheduled to sing selections from several operas during his performance alongside soprano Nina Morgana and violinist Elias Breeskin at Hill Auditorium in October of 1918. The performance was postponed until March of the following year due to the Spanish Flu pandemic.

The first singer to sell over a million copies of his recording, Caruso charmed audiences the world over as the first global media celebrity due to innovations in radio and television technology. His performance at UMS included an extensive repertoire of ten songs, all noted for their difficulty and beauty, including Souvenir de Moscow, Celste Aida, Una Furtiva Lagrima, Vesti La Giubba, and concluding with The Star Spangled Banner.

View from seats at Audra McDonald’s performance

We love this photo from the seats at Audra McDonald’s performance by @tayloranorton. Share your photos with us on social media using #umslobby.

Scoring 100 Years of Hill Auditorium

Meet Howard White, the composer behind the documentary celebrating the 100 years of Hill Auditorium: A Space for Music, A Seat for Everyone, the UMS documentary about our community over 100 years of UMS performances in Hill Auditorium. The documentary will screen on Detroit Public Television (DPTV) on May 19, 2013 at 5 pm.

An influential film score composer, particularly for documentaries, Howard White has lived in the Ann Arbor area for many years and is also the owner of The Omni Media Group. UMS’s own video producer and editor Sophie Kruz, the director of A Space for Music, A Seat for Everyone, sat down with Howard to discuss the process of scoring Hill Auditorium’s rich one hundred-year history.

Sophie Kruz: Can you talk a little bit about your background and how you got involved in this project?

Howard White: I’ve been in the music world for many decades. I’ve been doing composition in Ann Arbor for many years, and the last ten years, I have been focusing on film scores for narrative pieces and documentaries especially. That’s how we found each other, through a mutual acquaintance, Chris Cook, who is a really wonderful filmmaker in town. I’ve done maybe a dozen films for him. Being chosen for this project was a nice affirmation of years of work — learning the skills and building the repertoire — so that was very nice, for me to have the opportunity.

SK: What was the first film or TV show that you scored?

Howard White: It was pretty random, and it was a long time ago. I was just starting out in the music world, actually as a performer, producer, musician, and just starting my studio in Ann Arbor when somebody came to me from the art school of all places, asking me to make some music for a film for a master’s thesis. So I said, of course, not knowing anything about what they wanted or how to do it or what was needed. I wrote some songs and did some scoring, but back then, we didn’t have the tools like we have now.

SK: What are the tools you use to do the composition and the recording?

Howard White: In this industry, technology doesn’t drive innovation, but innovation drives technology. Maybe twenty years ago, we just used a multi-track instrumental tool, whereas now we have thousands of instrument samples at our disposal. Before synthesizers, you had a dedicated sample for every note that was hard-coded onto a chip that was embedded right in the hardware of the synthesizer. But now, with high speed processors and hard drives, you are able to store samples.

I’ve been evolving my sample library over the past ten years. To give you a size perspective, I have about a 40 GB string [instruments] library, and it’s just strings. It was recorded on a sound stage in Los Angeles by string players and an orchestra that normally scores film on that stage. There are other libraries out there that are more symphonic that are built for just big sounds, but mine was specifically developed for film scores so it has a nice bright notes and it’s not too big.

The library gives you every articulation, staccato, or sound, so it takes a lot of time to get the precision and the expression. The whole goal is to bring realism to a performance that is really electronic. As much as I would have loved to have scored this with a live orchestra, that’s just impossible these days — only the biggest films do that.

SK: What’s your process for composing? Do you write everything out and then start to record it electronically, or do you compose with a piano?

Howard White: Yes, it’s all piano triggered. I have a large controller keyboard, and it reaches out and grabs sound samples from my many libraries. With our project, I was able to look at the film and get a sense of what you needed, and then sketch out some ideas, and then keep developing and polishing and adding and subtracting from those ideas. Sometimes the idea would be there instantly, sometimes it would take days. I’d start 40 or 50 different pieces before I came up with the one that I sent to you.

SK: What research did you have to do to ground the film sonically to the community of Ann Arbor and Hill Auditorium over the last 100 years?

Howard White: I could search for musical inspiration pretty smoothly from sources as simple as iTunes to more obscure sources like the Library of Congress. I moved chronologically, decade by decade, going through the 100-year history of music I was working to encapsulate. I started in the 1920s, with the ragtime feeling, and then moved to the 30s for a mellower, jazzier sound. I started going down those paths and did some complete pieces, but I realized they weren’t working. The music was fine, but it didn’t match the picture. I could research and develop as much as I want to, but just because the period is correct doesn’t mean it works with the film. I ended up going a more classical, European-inspired route on a particular piece accompanying the story of Rosa Ponselle, and I think it worked really well.

There is a balance between what the music has to say and the story line. For example, when the Frieze Memorial Organ is introduced in the film, I thought it would be really nice to have an organ playing; it’s a little obvious, but sort of appropriate. The organ music that was most commonly played then was certainly Bach, and so I researched numerous inventions that he had done and found one that was lively but not too dramatic. I didn’t quote it exactly, but I used it as an inspiration for the piece.

When we got to the 1960s, I was able to bring in more rock and jazz music, which is closer to my background. I have studied and played classical guitar, but I also play solo piano with a more improvisational jazz style. I was struggling with this 60s piece, so I pulled out my steel-string guitar, because that’s a 60s folk style sound, and the piece just developed from there. When you have Merce Cunningham and John Cage on the screen, I moved to something more edgy and dissonant, but still with the folksy Latin style on top of it.

There was certainly no apprehension about creating this music, but I had to take a deep breath because this was going to be music for music lovers. It had to be up a notch in terms of intelligence and musicality because of the film’s audience.

SK: What are some of the similarities and differences between composing for film and composing for a group?

Howard White: I really like film composing because I’m a visual person. My whole business is interactive design and development, which is why working with music and visuals is a really satisfying melding of the two interests and skill sets. I love just playing and writing. Writing for film is really a special feeling. On one hand, you have the challenge of really amplifying the film and being in concert with the producer, directors of the film, versus when you’re writing music to be out there, then it’s only music. I focus mostly on film scores because that’s just so much more exciting and interesting for me, to work in that medium.

SK: If you were speaking to a young person who was interested in composing original scores for film or television, what advice would you offer them?

Howard White: I started in this business by building up a recording studio with a buddy of mine and working in Ann Arbor doing production for a lot of local bands. After we were done with the gigs, we’d go off and record commercials off the TV, turn off the sound, and score them ourselves. We made a reel and we’d go knock on the doors of producers and ad agencies asking for a chance, showing them what we could do.

My suggestion is to hook up with film makers and art students and anybody who’s doing visual production and do music for them, just collaborate. It’s really a networking world, but that’s all it is. If you have a good ear and you have a good skill set, you’ll make those connections. The key is to find people you need to find to be able to do the work.

Earlier in my career, I spent some time on the west coast to be more embedded in the music world. It was a good location because in big cities like LA, there are more opportunities for networking. There’s a lot you can do: sampling, sample playback, sample editing, and sound design. All of that is different from composing, but there’s a great market out there for sound designers. If you want to compose, you really have to know your theory and harmony, and you have to have a really good ear. You have to make orchestral decisions that make sense and work with the film and your audience. So there are a lot of subtleties and nuances to it that you need to study and just listen. I listen to film scores constantly, just to see what they are doing, why they’re doing it, and how they’re doing it to be able to have that background.

The opportunity to do this film was really special for me and I do absolutely want to thank you, Sophie, and UMS for trusting me to do the film. To hear the music in that beautiful auditorium and to know that it was embedded in a part of UMS history is really a personal thrill for me, and a very high point on my composition career at this point.

Interested in learning more? Listen to the complete interview:

People Are Talking: UMS presents Albert Kahn Architecture Immersion

Tell us what you thought about your experiences during the Albert Kahn Immersion! What was the highlight? Which visit was most interesting to you?

Tell us what you thought about your experiences during the Albert Kahn Immersion! What was the highlight? Which visit was most interesting to you?

This is the place to comment on the performance and talk to other people about what you saw and heard. Don’t forget to click the option to be notified when new comments are posted.

Learning Guide:

Backstage photo as Hamid Al-Saadi Maqam & Amir ElSaffar’s Two Rivers perform

Photo taken from backstage as as Hamid Al-Saadi Maqam & Amir ElSaffar’s Two Rivers performed on March 23. Did you go to the performance? Tell us what you thought.