UMS Presents Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra 2/19

Learn more about the show on 2/19: http://bit.ly/1tIkfO7

Student Spotlight: U-M First-year Student Isabel Park Sets Out to Explore Piano

Editor’s Note: Isabel Park is a first-year student at the University of Michigan, where she’s studying piano at the School of Music, Theatre, and Dance. This year, she’ll explore piano throughout our 2015 season, attending performances by pianist Yuja Wang and violinist Leonidas Kavakos (11/23), Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra with pianist Hélène Grimaud (2/19), Academy of St. Martin in the Fields with pianist Jeremy Denk (3/25), and pianist Richard Goode (4/26).

In the essay below, she explores her relationship with the piano. Follow her adventures and thoughts on UMS Lobby.

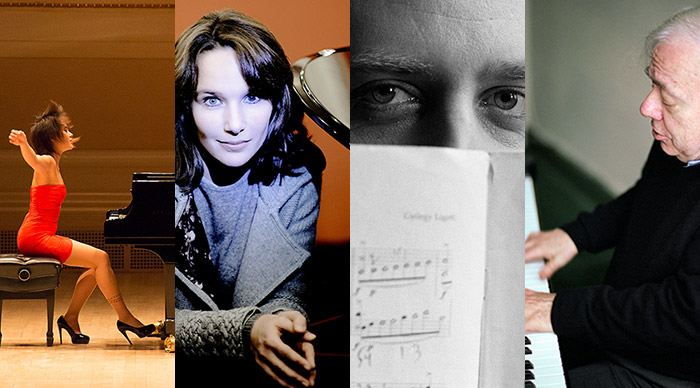

From left to right, pianists Yuja Wang, Hélène Grimaud, Jeremy Denk, and Richard Goode, all part of the 2014-2015 UMS season. Photos by Ian Douglas, Mat Hennek, and Michael Wilson.

The complexity of piano playing is astounding. Rarely do other tasks demand the intensity of full-body engagement that the piano does. Given its intricacy, piano playing can be crudely divided into technical and mental aspects; not surprisingly, a successful piano performance ultimately relies on the pianist’s adeptness in both areas, and the relative importance of each with respect to the other remains a highly disputed topic amongst pianists.

Is technique vital?

However, the relationship between a pianist’s musicianship and technical capacity is not so mutually complementary as it is often thought to be, but rather one-sidedly supplementary. Improving an aspect of one’s playing does not necessarily do the same for the other. Instead, technique supplements ability to express with a boundless sense of musicianship and musicality. Solid technique is not only a desirable, but vital to superlative piano playing that encompasses both outstanding technicality and depth of expression.

It is natural to conclude that the technical facet of piano performance is easier to approach— not necessarily easy— in the sense that improving one’s technique can be done methodically. While musicianship primarily concerns the mind, a highly equivocal part to deal with, technique mainly deals with the pianist’s physical body. The pianist can pinpoint and address specific parts of the body to enhance corresponding areas of technical facility. Not only that, technical development is easier to facilitate than musical growth because it can be measured by a universal numeric system in the form of tempi and durations, which enable objective comparisons and indications of improvement.

A unique body engagement

Yes, piano playing demands an exceptional degree of body engagement. Not only are we exercising hand-eye coordination of infinitesimal detail and precision, but the feet are also working their own set of motion. Even more uniquely, playing piano requires an unusual amount of bodily symmetry. A string player holds and draws the bow with her right hand while the left hand takes charge of fingering; similarly, a brass player manages valves with the left hand while the right hand provides support. On the piano, the hands of a pianist cover the very same keys, able even to crossover, to exchange control over different ranges, which truly gives a pianist’s hands symmetric action and equal opportunity. The bodily symmetry of piano playing also applies to the feet as they share access to the three pedals— one foot per outer pedal and a third equally distanced between the other two.

This quality of piano playing has a rather burdening implication: a pianist’s left and right hands and feet must be perfectly equivalent in terms of technical dexterity. The solution seems unrealistically simple— train each half of the body identically. Unfortunately, this proves problematic because most of us are born with dominant hands and legs that naturally possess a higher level of technical proficiency. The pianist is left with a challenge, alongside many others, of developing an artificial ambidexterity in order to master the symmetric art of piano playing.

Interestingly, piano playing is also set apart from the playing of other instruments by a factor of non-symmetry. This happens in two different, but related, respects— clefs and voices. Aside from other keyboard-natured instruments ( organ, harpsichord), the piano is the only instrument that requires the player to simultaneously read and internalize two different clefs.

A polyphonic ability

But above all, the pinnacle of piano playing and its grandeur is derived from the pianist’s polyphonic ability. Once the pianist considers the multitude of voices that he or she produces, the asymmetric factor becomes intensely complex. Although the prime examples of polyphonic music are the Bach fugues that showcase up to five voices at a time, essentially all piano music encompasses varying degrees of polyphony.

The abundance of notes is not an arbitrary flux, but rather multiple voices concurrently played. The pianist’s responsibility is to prioritize: which is the melody and which are accompaniment? He or she must voice accordingly in order to clearly and efficiently deliver the melody. The greater individuality the fingers possess, the easier this is, since the hand playing the melody is often playing an accompanying voice as well.

But the true challenge of playing polyphonic music extends beyond our fingers. The pianist’s brain must be able to process what is comparable to multiple languages to deliver a cohesive, collective body of sound. This also challenges the ears. The problem usually arises at the point of memorization. At this point, the pianist might be so accustomed to knowing the piece as the collective body of sound that she strives to produce; however, complete memory requires a detailed knowledge of each and every line of sound within the piece as well.

Being on stage

Finally, no matter how prepared, many external factors tamper with a performer’s mental condition when on stage. Performance anxiety almost always results in hyper-awareness, oversensitivity to one’s surroundings and one’s own playing, even. In many cases, the performer becomes so aware of miniscule details that perception is distorted. She could hear things within the piece that seem new or even forget the first note.

In any case, the goal is to replicate this hyper awareness in the practice room so that one simply cannot be ove-aware on stage. To combat this, isolate each sense— hearing, sight, and touch— and focus entirely on it. This level of focus is extremely difficult to maintain for prolonged periods, so dividing the movement or piece into compact sections is more productive.

Why see performances?

But given the endless ways to learn through practice and internalizing, nothing can directly replace the inspiration and teaching that transpires during a live performance. That’s why I am particularly excited to see Yuja Wang, Hélène Grimaud, Jeremy Denk, and Richard Goode live this season.

Yuja Wang has visited my hometown, San Francisco, quite a few times, and I’ve missed all of those performances. The endless mentions of her amazing technical facility and her controversial outfits have raised my curiosity as a fellow female pianist. As for Hélène Grimaud, I first heard of her through a pianist friend who raved about her live performances. Not one to praise easily, my friend has inspired me to find out first-hand what’s made her playing so extraordinary. I read Jeremy Denk‘s blog extensively, and love his very deep sense of understanding of music, something I consider quite important to good performance. On the contrary, Richard Goode remains quite a mystery to me; I know that he is part of the piano faculty at Mannes and have heard highly positive reviews of his performances. I cannot wait to see him perform live to discover what it is about him that captures those around him.

Interested in more? Follow Isabel’s thoughts and adventures here on UMS Lobby. She’ll participate in our “People are Talking!” conversations after each performance she attends.