What is it about Bach?

“I have this to say about Bach’s works: listen, play, love, revere – and keep your trap shut.” — Albert Einstein

Recently, I stumbled upon an NPR interview with Sir András Schiff about his Well-Tempered Clavier project; in it Schiff shared his love of J.S. Bach and the special connection he feels to the composer.

As a bass player I’ve rarely had the good fortune of having solo pieces written by big-wig composers; instead, I’ve usually begged, borrowed, and stolen from cello, the violin, and the viola repertoires. It’s a blessing and a curse; I’m never made to perform only music expressly written for the bass, but I’ve also rarely had the pleasure of playing a piece written with my comfort and capabilities in mind. J.S. Bach is one of the many composers who never wrote for the bass, but whose music I’m perfectly happy to play anyway.

Bach is like snorkeling

John Eliot Gardiner, the author of the Bach biography Music In The Castle of Heaven, jokes that Bach is like snorkeling. “Being in Bach’s music has that sense of otherness: it’s another world we enter, as performers or listeners. You put your mask on, and you go down to a psychedelic world of myriad colors” (Burton-Hill, 2014)

In my experience, every musician has an arduous yet ardent relationship with Bach. His music, like no other, seizes us, conquers our hearts and souls, and spits us back out slightly changed. Each listen brings a slightly new experience.

Bach and me

The first time I played music by J.S. Bach was in high school band. We used a Bach chorale each class to focus on phrasing and intonation. I looked forward to these fifteen minutes every day. I found that being embraced by the wholehearted reverberations of the other musicians’ Bach-playing left me with a kind of peace and calm unmatched by anything I’d felt before. Each detail of the chorale seemed minute and gargantuan at the same time, and I could find the patience to work on problem areas in my own playing because my love and respect for Bach was so great.

When I arrived at the University of Michigan School of Music, Theatre & Dance, the first piece bass professor Diana Gannett assigned me was the Gigue in the First Cello Suite. Playing through a Bach Cello Suite is perhaps one of the most challenging and rewarding acrobatic feats that I’ve forced upon myself as a bassist. I have listened to countless cellists perform Bach’s masterworks for cello, so my competitive self is disappointed when I fall short of the standard they’ve set; nevertheless, these cellists have also helped define my musical goals. Bach keeps. Bach keeps me humble while giving me unflagging energy for the process of becoming a better musician.

I would never consider performing Bach for an audience; I find that my relationship with Bach is about the intense personal experience of playing his music for my ears alone. It’s become a morning ritual, something I cannot live without.

As Schiff says in his interview, playing Bach is a work in process that never ends. He continues to say that there are new stations that you arrive at on your exploration of the mystery of his music, but you can only hope to see a wider horizon along the journey. I’ve only just begun my journey as a professional musician, and my love for Bach is sure to be what sustains me.

Are you a lover of Bach? If not, what piece of music or what composer is “sacred” to you?

Gil Shaham performs Bach’s complete sonatas and partitas with original films by David Michalek on March 26, 2014.

Take a break and listen to Mstislav Rostropovich play Cello Suite No. 1 in G major BWV 1007

Sources:

Burton-Hill, Clemency (2014, September 17) Can Any Composer Equal Bach? BBC.com. Retrieved on July 30, 2015. http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20140917-can-any-composer-equal-bach

Explore: Connections Between UMS and U-M Museum of Art

Visual and performing arts have a close relationship. We asked our partners and friends at UMMA (U-M Museum of Art) to link performances on the UMS season with visual art works that are part of the museum’s permanent collection.

Related performance: Tanya Tagaq in concert with Nanook of the North

February 6, 2016

Artwork: Kenojuak Ashevak (Canadian, 1927-2013). Sun Owl, 1963. Stonecut print on paper. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Eugene B. Power, 1964/2.103

Artwork: Kenojuak Ashevak (Canadian, 1927-2013). Sun Owl, 1963. Stonecut print on paper. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Eugene B. Power, 1964/2.103

Like Tanya Tagaq, Kenojuak Ashevak was from Nunavut and her art was inspired by her Inuit experience. She often depicted animals from the Arctic such as this owl, but, also like Tagaq, she relies on her creativity and imagination. Ashevak explained that she drew as she thought, and so she produced spontaneous and improvisatory images.

Related performance: Camille A. Brown & Dancers: Black Girl — A Linguistic Play

February 13, 2016

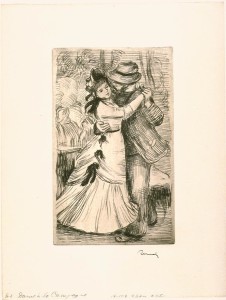

Artwork: Pierre Auguste Renoir (French, 1841-1919). Dance in the Country, c. 1890

Artwork: Pierre Auguste Renoir (French, 1841-1919). Dance in the Country, c. 1890

Soft-ground etching on paper. Museum Purchase, 1959/1.102

In Renoir’s beloved image of country dance we see an earlier century’s ritual of recreation. Although more restrained than contemporary dance, it represents social dance, one of the inspirations for choreographer Camille Brown’s work.

Related performance: Nufonia Must Fall

March 11-12, 2016

Artwork: P. Grasnick (n.d.). Aelita, 1924

Artwork: P. Grasnick (n.d.). Aelita, 1924

Lithograph on buff woven paper, laid down on canvas. Gift of James T. Van Loo, 2013/2.233

This poster is for the movie Aelita, which is often called the first Soviet science fiction film, created during the sometimes hope-filled beginnings of the Soviet Union. A mysterious radio message is beamed around the world, and among the engineers who receive it are Los, the hero of the film. Aelita is the daughter of Tuskub, the ruler of a totalitarian state on Mars. With a telescope, Aelita is able to watch Los who obsesses about being watched by her. He builds a spaceship and travels to Mars where he is thrown in prison, begins a proletarian uprising and experiences the confusion of reality and fantasy. While Nufonia Must Fall is no sci-fi film, it is based on a graphic novel of the same title, and viewers might find similarities between the genres.

Related performance: Gil Shaham Bach Six Solos

with original films by David Michalek

March 26, 2016

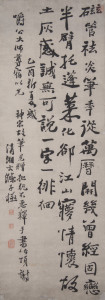

Artwork: Shitao (Shih-t’ao; Chinese, 1642-1707) Ode on a Wanli-era Imperial Brush Ink on paper, 1705. Museum purchase made possible by the Margaret Watson Parker Art Collection Fund, 1965/2.75.

Artwork: Shitao (Shih-t’ao; Chinese, 1642-1707) Ode on a Wanli-era Imperial Brush Ink on paper, 1705. Museum purchase made possible by the Margaret Watson Parker Art Collection Fund, 1965/2.75.

Taking an honored and beloved corpus of music from the past, Gil Shaham transforms its familiar beauty into a fresh, contemporary work of art. Similarly, Shitao receives a beautiful gift, a porcelain-handled calligraphy brush, from an earlier generation and uses it to write a poem and create a calligraphic masterpiece. The era and form are new but the inspiration is classic.

Related performance: Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán

April 1, 2016

Artwork: Artist Unknown, Mexican, Colima Culture Seated Figure, c. 700 Terracotta Museum purchase made possible by a gift from Helmut Stern, 1983/1.355Artist Unknown, Mexican, Colima CultureSeated Figure, c. 700TerracottaMuseum purchase made possible by a gift from Helmut Stern, 1983/1.355

Artwork: Artist Unknown, Mexican, Colima Culture Seated Figure, c. 700 Terracotta Museum purchase made possible by a gift from Helmut Stern, 1983/1.355Artist Unknown, Mexican, Colima CultureSeated Figure, c. 700TerracottaMuseum purchase made possible by a gift from Helmut Stern, 1983/1.355

This lovely terracotta seated figure is an example of the native arts and culture celebrated by Mexican visual and musical artists. Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán transform a regional folk music into a world-class art form.

Related performance: Zafir: Musical Winds from North Africa to Andalucia

April 15, 2016

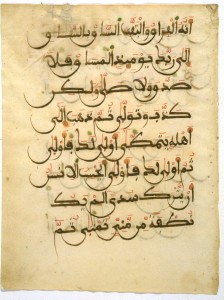

Artwork: Artist Unknown, North Africa Qur’an manuscript leaf in Maghribi script, 13th century Ink, red ochre, paper Museum Purchase, 1959/1.146

Artwork: Artist Unknown, North Africa Qur’an manuscript leaf in Maghribi script, 13th century Ink, red ochre, paper Museum Purchase, 1959/1.146

For Muslims, Arabic script, representing the language of the Qur’an, is a thing of sublime beauty. This page is written in a script called Maghribi, a variation of the earlier, angular, Kufic script. Maghribi features sweeping curves that loop across the page and was developed in North Africa and Spain. This Qur’an page combines traditions of the Middle East, Spain and North Africa as does the music of Simon Shaheen and Zafir.

Interested in more? Visit the U-M Museum of Art today.