Student Spotlight: Could You Repeat That? and Other Stories from Paris

Editor’s Note: Clare Brennan is a junior at the University of Michigan. This past summer she interned for ANRAT, a theater research company in Paris co-founded by Emmanuel Demarcy-Mota, director at Théàtre de la Ville. Their production of Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author comes to UMS October 24th and 25th.

The summer of 2014 consisted mainly of getting lost. As a first-timer to the grand city of Paris, or to any sort of international travel for that matter, I had incessantly practiced the correct way to ask for directions to the bus stop during my entire eight hour flight. Before I could get a “Bonjour” in edgewise, a bored flight attendant directed me towards my destination in perfect English, and I was on my way.

I’d gladly forget my first trek from the airport to the dorms, dragging my two oversized suitcases across town, but after the jetlag wore off, I started to get the hang of things. I became a lover of maps, discovering the metro system as quickly as possible. That knowledge invariably went out the window as soon as summer construction began. Eventually, I started ending up in the same places, and what was once a completely strange conglomerate of streets started feeling a little more like home.

Once settled in, I dove into the incredible wealth of theater surrounding me. With over 150 professional theaters within its city limits, Paris never let quantity deteriorate quality. One of my first shows was Ionesco’s Rhinocéros at Théàtre de la Ville. I had missed the production when it came to UMS last season, and was so excited when fellow UMS intern Flores Komatsu offered up a ticket to join him. We met at the theater and crossed one of the many bridges that connect the vastly different banks of the river to find a small café for dinner. A group of men of various ages played pétanque, the French equivalent of bocci ball, on a dirt patch next to us, a common pastime on summer evenings. Obviously American, we prattled away, catching up on upcoming projects, book recommendations, and travel plans. Eventually, the couple from Colorado sitting next to us struck up a conversation, and after twenty minutes we had learned the story of their ex-pat daughter and swapped recipes for favorite dishes we’ve discovered. Caught up in conversation, we barely realized we were running dangerously close to curtain time. We sprinted back to the theater and found our seats with just enough time to absorb the atmosphere.

*

I love theaters. Between their velvet curtains and cushioned seats, both actor and audience member gain some security to suspend their disbelief for a while and hear a story. I appreciate that sense of trust that seems built into the walls, and I always try and find it again before every show I see.

At Théàtre de la Ville, the most striking quality I found was its size, housing around 1,500. Our Monday evening show was sold out, and as I looked around, I noticed that most of those in attendance were around my age. In my exploration of the arts at home, I’ve often found truly invested younger patrons more difficult to find. There, young people come to shows, stay for talkbacks, and attend season premieres; Théàtre de la Ville’s season announcement, for instance, packed the house just as tightly as their best-known runs.

Photo: Le Palais de Pape, where “I Am” played during the Avignon Theater Festival in July. Photo by Clare Brennan

The house lights dimmed, and I experienced again what would quickly become one of my favorite culture moments abroad. Before an actor ever sets foot on stage, a score of audience members will audibly shush one another. It will be hard to forget my first experience of this sort, as the majority of hisses were directed at me. Foreign air and a lack of sleep had left me sick for a couple weeks, and, apparently, I thought that the start of the Moroccan acrobatic performance Azimut at Théàtre du Rond Point would be a lovely time for a coughing fit; the surrounding patrons did not. I quickly picked up this less-than-subtle social cue, and by the end of my two months, I was joining in as passive-aggressively as possible. Strong reactions like this were never out of place. At the Avignon Theater Festival, a production of Lemi Ponifasio’s I Am, a World War II homage in dance, produced critical laughter, side comments, even a small exodus after a particularly difficult movement. However, with this piece included, I also never saw a performance without at least five minutes of applause at the close.

*

Seeing theater in a foreign language took a bit of adjustment. Rhinocéros opens with a beautiful monologue. I couldn’t tell you what the first few lines mean now, as I was still looking for surtitles within the first few moments before I remembered where I was. I did have opportunities to try reading French surtitles during a Dutch production of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead and a Japanese kabuki style of the Mahabharata. Reading and translating French while listening to another language with which I had no experience left my American brain a little withered, but it did help me to abandon any pretenses I had when I arrived and dedicate a couple of hours to a completely new experience. Or four and a half hours, in the case of the Dutch Fountainhead. (I have to admit, I dozed off for about twenty minutes of that. I read the book in high school, so that counts, right?)

That night, Flores and I left the theater and lingered on the rainy sidewalk with a crowd of theatergoers doing the same. We all shared our thoughts, compared interpretations, raved over actors, and tried to weave our way through the denser moments. We said our goodbyes for the night, and as I turned to leave, I realized that I was pretty disoriented. I was lost in Paris again, but what else was new. Theater abroad left me dizzy and buzzing, not quite sure of where I stood but happy that I was there. I was used to the feeling by now, and there could be worse places to get turned around. Paris is a city for wandering, anyway.

Student Spotlight: Summer with Théâtre de la Ville

As part of the 21st Century Artist Internships program, U-M students spend several weeks working with companies that are part of the UMS season. In 2014, 21st century student Héctor Flores Komatsu worked with Théâtre de la Ville in Paris, France.

Below, Flores shares his travel stories with the company. Théâtre de la Ville returns to Ann Arbor with L’État de siege (State of Siege) on October 13-14, 2017.

El Espíritu Oculto de la Olvidada Europa

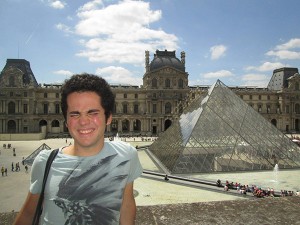

Photos: On the left, Flores in Paris. On the right, the company during dinner. All photos by Flores Komatsu.

The word “summer” has always had a very homey and rooted connotation to me. Road or plane trips that traverse borders were a staple of my upbringing. I’d look forward to the summers of eternal spring in my Mexican hometown, under the shade of the oscillating bugambilias, tantalized by the scent of Sunday morning house-spiced chorizo at my grandfather’s. If I owe my curiosity and affinity for the intercultural richness of the world to anything, it’s to the very familiar act of crossing borders.

I finally had the opportunity to venture away from the continent this summer, after Jim Leija [UMS Director of Education & Community Engagement] called to invite me to intern for UMS in Paris as part of the new 21st Century Artist Internship. I’d be leaving for France in three weeks.

And so, I took-off to Europe to intern with Théâtre de la Ville, Paris’s cultural institution for the performing arts (as well as an Ann Arbor and UMS favorite, having performed Ionesco’s Rhinocéros at the Power Center two seasons ago). I’d be working as a rehearsal assistant and media collector for their upcoming touring production of Six Characters in Search of an Author (to be performed at the Power Center October 24-25, 2014). All this presented itself, serendipitously, a mere two weeks before the end of my sophomore year at the University of Michigan — truly, an open door. Little did I know that, thanks to continuing serendipity, I wouldn’t set foot back in Ann Arbor until a few days before this Fall term.

Within minutes of boarding that plane, I instinctively felt that I was about to experience the most gratifying, unsettling, and enriching journey of my short years. It became a summer that has helped me to unearth my roots and left me with a hunger that’s been eating me alive, yet thankfully not eating me dead. I hope I can awaken a similar appetite in readers of this blog with my anecdotes from my time with Théâtre de la Ville (TDLV) and my first journey into the Old World.

Un Jeu des Rôles au Théâtre de la Ville

Photos: On the left, the two directors: Théâtre de la Ville director Emmanuel Demarcy-Mota and actor Alain Libolt, who plays the role of “Director” in Six Characters in Search of An Author. On the right, rehearsal with sub-titles.

Casually crossing the Pont Neuf on the Seine on the way to my first day, checking-out Notre Dame from the smoker’s balcony (though I don’t smoke), and then finishing my paperwork as the sun set against the Eiffel Tower seemed either the best cliché or too surreal to be true; but it was true, beauty on every corner. However, this type of initial beauty can grow stale with habit, and I quickly found beauty in the fondness my companions as well.

This type of beauty emerged when sharing a simple picnic with the company by the river at lunch, for example. I think the the vitality of a company originates from the unified pulse of its ensemble, that pulse that is universal in any theater venture, regardless of country. Sure, “stage-right” in French might be “the garden” (you can imagine the confusion for me, given that there’s an actual garden in the production). Sure, there may not be such a thing as blocking notes for re-stagings. And maybe the reasons for doing theater at all are very different. Still, the collaborative nature of theater is undeniable across the globe.

Six Characters in Search of an Author is play in which the dramatic truth is juxtaposed with immediate reality. Actors play actors, for example, while directors coach actors to play directors. The lines between performance and reality are crossed. For me, the ideas were constantly in translation as well. Yours truly was tasked with sub-titling the originally Italian text of the play (which is performed in French) into English. Ultimately, the goal for everyone involved, the director, the ensemble, and myself, was the same: To connect the inner life of the play to the outer life of the audience.

La culture ne marche pas!

Photos: On left, sunset as viewed from the theater. On right, the theater, “X”-ed.

I spent two weeks in Italy (turns out speaking Spanish with an Italian inflection doesn’t actually mean you can speak Italian), and upon my return to Paris, I found culture in distress. “Culture,” substantially subsidized by the government and also supported by patrons, was immobilized and in peril due to some impending changes. To put it simply, recent overhauls to labor laws were to compromise the financial security, primarily through alterations to unemployment benefits, of “gypsy” professionals (including actors and stage hands), changing a system which (although not without faults) had long kept the performing arts alive, thriving, and, more importantly, relevant to the society.

The strongest impact on Théâtre de la Ville occurred during its annual city-wide performing arts festival Chantiers d’Europe. The festival saw various performances, all brought from abroad, cancelled as theater venues around the city shut down as part of a strike. TDLV, however remained strong. I learned perhaps my biggest lesson from [Théâtre de la Ville director] Emmanuel Demarcy-Mota when I saw him rally and inspire the company to, instead of shutting down the power of the stage at this time of turmoil, take advantage of the theater’s influence on the city and its audiences. In July, the façade of the theater was crossed with a large white “X” of defiance.

In the midst of the strikes came the opening night for a sold-out run of Pina Bausch – Wuppertal Tanztheatre, a yearly visitor and old friend of TDLV. The company was to perform the “wall”-breaking (both literally and figuratively) Palermo, Palermo. Dramatic truth came from an unexpected place in the bravest and most honest theatrical moment I got to witnessed in France.

Photos: On left, Michael Chase. On right, company and stagehands bow together.

The co-head of the theater, Michael Chase, a reserved man of soft-spoken, tactful, iron words stood center-stage along his company in front of a full house. He softly said that without the workers of the theater, “La culture ne marche pas.” He bent down towards his signature red shoes, untied and removed one of them. He took a step forward as the rest of the company followed his actions.

Later, at the end of the performance, the dancers invited the stagehands, who had built for them, everyday, a brick wall that spanned the proscenium arch, and which tumbled and consequently needed rearranging by the stagehands mid-performance in plain view of the audience, to the stage. They joined the dancers. Everyone took a bow, every single one of them an artist without which “culture wouldn’t move”. And then the curtain fell.

Updated 6/2/2017.

Rhinocéros by Eugène Ionesco, a man among his ex-peers

Editor’s Note: Théâtre de la Ville perform Rhinocéros, a seminal theater of the absurd play, this October.

Sometimes, absurdity makes much sense.

In a peaceful village somewhere in France, a cat is being run over by a rhino. The rhino is a special one: not a wild, exotic animal escaped from a zoo, but some sort of a “human-rhino,” a human being turned into a beast. The political farce at stake in Ionesco’s play Rhinocéros is about the humanity of this inhuman epidemic through which almost everybody converts to the rhino-mania.

Beyond the absurdity of the improvisation of this rhino-circus lies the fable of resistance and conformity, or, to put it into perspective, the resistance to the pressure of conformity. But when everyone hurries to wear the same uniform, this rush to conform can actually trigger a minor, yet heroic counter-transition: from coward and anonymous character to brave and committed humanist. Such is the case of Bérenger, an insignificant employee on the verge of either alcoholism or existential vertigo (maybe both), who comes out as an unexpected résistant when everything around him urges him to become a rhino.

The theater of the absurd is subject to many interpretations, and most commentators have praised this play for its creative critique of the rise of totalitarianism. Some have specifically seen a reference to the Vichy episode (1940-1944), when the majority of French accepted collaboration with Nazi Germany. This massive collaboration was so degrading and disgraceful for the myth of France fighting fascism that, that, once Hitler was defeated, French people rephrased History and reinvented themselves as a nation of résistants during the collaboration – a case of bad consciousness, as would say Sartre.

A more personal interpretation is that Ionesco, as he was living in Romania during the 30s, witnessed the rise of a xenophobic, nationalist and anti-Semitic movement, the Garda de Fier (the Legionary Movement), which repelled him and made him consider France as a land of escape. Ionesco was deeply hurt and confused by the fact that his close friends, Emil Cioran and Mircea Eliade, became enthusiastic about the Legionary Movement. Once they would gather again, this time in Paris after WW2, Cioran and Eliade would hide their embarrassing past and Ionesco would not mention or write explicitly about their former “political fever.” In this perspective, the play Rhinocéros, published in 1959, might be his personal meditation on the loneliness and the legitimacy of the one who resists until the end against all the others, including his friends.

Unfortunately, nowadays, the rhinos depicted by Ionesco are not an endangered species, and Ionesco’s fable about the tensions between resistance and conformity continues to speak to a large audience worldwide.

At some point, if not every day, one finds himself at the crossroad between the temptation to fit the rhino-mania of his times and the interior duty to fight against the normalization of minds and actions. The last sentences “Je suis le dernier homme, je le resterai jusqu’au bout ! Je ne capitule pas !” (“I am the last human, and will remain so until the end. I don’t surrender!”) cannot fail to strike us by its invigorating humanism.