Tossing Grenades At Shakespeare, and other lessons from Propeller Director Ed Hall

All week long I’ve been hearing people sing the praises of Propeller director Ed Hall. In rehearsals he’s decisive but incredibly open to ideas, firm but flexible, actors say. Company manager Nick Chesterfield told me Hall is “incredibly inclusive. Ed has a very loose way of working, in that he knows what he wants, but he doesn’t lay it on the show. I’ve never experienced a more generous environment.”

All week long I’ve been hearing people sing the praises of Propeller director Ed Hall. In rehearsals he’s decisive but incredibly open to ideas, firm but flexible, actors say. Company manager Nick Chesterfield told me Hall is “incredibly inclusive. Ed has a very loose way of working, in that he knows what he wants, but he doesn’t lay it on the show. I’ve never experienced a more generous environment.”

Having now seen Hall up close, in a riveting exchange Thursday morning with a dozen or so BFA directing students from the UM School of Music, Theatre, and Dance, I get what everyone means. Tidily dressed in a blue Oxford-cloth shirt and slacks—and looking more like a businessman on casual Friday than the director of one of Britain’s most explosive theater companies—Hall spent nearly two hours talking with students and members of the UM theater faculty and gamely fielding questions. He was affable and engaging, and the students clearly gleaned a lot from the exchange. As did I.

About the playwright with whom he’s most closely associated, Hall confessed, “If I go more than 18 months without directing Shakespeare, I go through withdrawal.”

About building a scene: “The opposite is always true. If you have a scene where two people love each other, you have to find out what obstacles they have to overcome in order to love one another.” Ditto with a scene in which two people profess to hate each other—find out what draws them together. “That’s the source of the tension, the drama.”

When directing Shakespeare, Hall often starts with the toughest scene. “If you want to do something big, get it in early.”

On directorial control: “Have a plan, but be critically prepared to let it go out the window. Give yourself up to the process of rehearsal. It’s like stepping off a cliff—if you don’t do it, the actors won’t do it. But they have to know you’re going to be there to catch them. It’s an enormous paradox—trying to control something you’re essentially letting go of.”

Much of what Hall said helped explain the great inventiveness I saw onstage in both Richard III and Comedy of Errors, whose wit and sheer physical brawn had Thursday night’s audience literally oohing and ahhing throughout the evening. Earlier in the day Hall told the UM student directors, “The more I retreat [as a director], the greater the party is onstage.” And oh, what a party.

Now in his mid-40s, Hall has directed 14 productions of Shakespeare. The first, Othello, defeated him. Hall said he tiptoed around the play, trying to do it “right,” and quickly learned his lesson. He now throws “as many grenades as possible against the notion of directing Shakespeare.” That’s not to say he’s not fiercely thoughtful about the texts—as evidenced by these razor-smart productions—but experience has taught him there’s not much to gain from reverence. Hall decries “sunset” acting—where performers look off into the distance with misty eyes while intoning the great lines (“Now is the winter …”). Says Hall: “As a director, you have a duty to cast off the burden of those lines.”

A few more observations that help illuminate the process behind the provocative shows now playing in A2:

“Shakespeare didn’t do scene changes. The moment you do a piece of design that requires the play to stop, you lose momentum.”

“The chorus is context. The context changes and evolves as you rehearse.”

“Acting Shakespeare, you have to be like a good lawyer—you have to be able to deliver rhetoric.”

“There’s no subtext in Shakespeare. The text is where the character is, and the subtext builds itself up from the text.”

“The rehearsal room is a temple for the people you’re working with. It’s a safe place. It’s a private place.”

“The more mistakes you make in rehearsal, and the faster you make them, the quicker you get to the truth. It’s all in the doing.”

And, for the audience, in the going. Go.

Richard III Recap: Taking Sides

We generally do not side with the homicidal maniacs of a given story. For example, we may see Iago’s point of view in Othello, but in the end, after all he does to ruin the lives of those around him, do we really feel all that sorry for his arrest and eventual torture?

We generally do not side with the homicidal maniacs of a given story. For example, we may see Iago’s point of view in Othello, but in the end, after all he does to ruin the lives of those around him, do we really feel all that sorry for his arrest and eventual torture?Propeller: Q&A with UMS Programming Director Michael Kondziolka

All week long guest blogger Leslie Stainton will be following the Propeller theater company residency in Ann Arbor. She starts the week with a Q&A with UMS Programming Director Michael Kondziolka about how he learned about Propeller.

For years, Michael Kondziolka, UMS’s Programming Director, has been my go-to guy for all things cultural. If Michael says see it (as he does about Propeller), I move heaven and earth to heed the call. So I asked him how Propeller caught his eye…

MK: Through the RSC—the gift that keeps on giving. Caro MacKay, one of the RSC producers I worked with 10 years ago on the Henry VI/Richard III tetralogy here in Ann Arbor, brought to my attention the work of Propeller and Ed Hall in general. Ed Hall is the son of the British director Sir Peter Hall—and Caro said, “I think he’s doing important work. You owe it to yourself to see it.” So I checked it out and was blown away by the sort of arch, vaguely edgy sensibility. At the same time, they had a lot of integrity and respect for the text. This wasn’t about trashing Shakespeare—it was about bringing a young, fresh, edgy sensibility to the text. I remember leaving the theater and going to King’s Cross Station to get my sleeper car up to Edinburgh for the festival there. I’d planned to sleep on the way up, but we stayed up all night and talked about the production.

How does Propeller fit into the broader UMS vision for theater—and for Shakespeare in particular?

MK: Over the long term we want to celebrate the work of companies like the RSC and the Globe Theatre, but we also want to start painting a picture of the versatility and the broadness of Shakespeare, and of just how wonderfully elastic these texts are. It’s one thing to understand that intellectually, and it’s another thing to actually witness it. Well, this company will help people with that!

How different will the Propeller experience be from, say, the RSC?

MK: I’m not so sure it’s going to differ that much. I think that ultimately what people are going to respond to and recognize is the absolute craft, the absolute training that’s in evidence, and more so than almost anything, this wildly profound commitment to ensemble. For people who don’t go to the theater every day, there’s something so special about the mystery and magic of a truly trained ensemble working together over an extended period of time.

So in a nutshell, what’s Ed Hall’s take on Shakespeare?

MK: I would imagine that that’s what’s going on in Ed Hall’s mind is, how do you take this potentially strangling tradition—especially in the UK—how do you take the weight, the smothering weight of this tradition, and keep it alive? And keep it relevant and exciting and engaging and fresh? I think that’s one of the questions he’s trying to answer. I can imagine really great things for a company like Propeller in Ann Arbor—great audience reaction, a real recognition of the power, strength, integrity, and impact of this company’s work, and how that could build over time. I don’t want to make any predictions, but I have a feeling.

VIDEO: Men in Dresses! Blood & Gore! Watch the Propeller Trailers

Next week, the UK’s all-male Shakespeare troupe Propeller (led by acclaimed director Edward Hall) will be taking Ann Arbor by storm with stellar new productions of Richard III and The Comedy of Errors. The shows have been receiving rave reviews and great word-of-mouth from audiences. The video trailers for both productions are here — and they are pretty awesome.

If you want to learn more about the company, you can check out their blog and this blog post from UMS staffer, Mary Roeder, who visited the Propeller company in the UK while they were rehearsing Richard III last fall.

Dispatch from across the pond: Shakespeare is on the way!

Yesterday was a very important day. In addition to marking the start of the one week countdown to our nation’s Thanksgiving binge, it was also the opening of Propeller’s production of Richard III at Coventry Belgrade. Propeller, an all-male Shakespeare company, appears here in Ann Arbor March 30 – April 3, 2011 with both Richard III and The Comedy of Errors.

At the end of last week I took a rather last minute trip to London for a long weekend (Who takes a last minute trip to London you might ask? Someone with a friend employed by an airline. The fabulous life is achieved by things like knowing pilots. And stage managers for important theater companies. And being granted a vacation day allotment. Dumb luck and circumstance.). While there, I was able to pop in on Richard III rehearsals for a couple of hours.

I had recently learned via Facebook that my friend Laura, whom I met while she was the deputy stage manager (DSM) for the Globe Theatre’s production of Love’s Labour’s Lost (presented by UMS in October 2009) that she would again be touring to Ann Arbor…this time as the DSM for Propeller! Exciting, right? So of course, when I found out I’d be going to London, I asked her if I could stop by rehearsals.

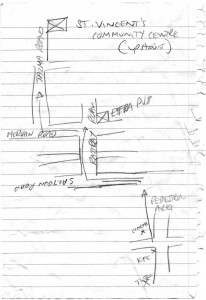

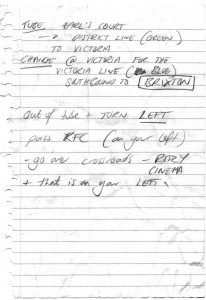

Laura gave me a call time of 9:45am on Friday and told me to report to Brixton St. Vincent’s Community Centre where the company was rehearsing. I asked her for explicit instructions on how to find the place. Being the well-armed stage manager that she is, she whipped out a spiral notebook and pencil (stage managers never use pens), drew me a map (Exhibit A), and illuminated it with written instructions (Exhibit B).

Friday morning came along, and I found the place with no trouble, even arriving with time to spare, a testament to Laura’s fine directions. I met a few members of the cast and crew and Propeller’s director, Edward Hall. The space was very small (read: I couldn’t hide like I had planned), and I was nervous that my presence would be an intrusion. Turns out my fretting was for naught, as everyone greeted me warmly. I was met with a cup of tea and questions like…”Is Michigan cold?” Yes. “Will it be cold when we’re there?” Probably. “Is Michigan like Minnesota?” They’re both funny-shaped and cold. So yes, probably.

So what should you as a potential audience member know about this company? Well, as their website says, Propeller “seeks to find a more engaging way of expressing Shakespeare” and “[mix] a rigorous approach to the text with a modern physical aesthetic.” In the case of Richard III this means the inclusion of the decidedly non-Shakespearean electric guitar, among other things. A crucial part of every Propeller production is the music. All of the music in their shows is either written by the company or sourced from music they know, and they have a tradition of producing most, if not all, sound effects live from the stage. Jon Trenchard who plays Lady Anne in Richard III (yes, you read that correctly…remember that part where I said this is an all-male company?) and Dromio of Ephesus in Comedy, is also creating and arranging music for both productions. In two incredibly entertaining installments, Jon blogs about the musical rehearsals for Richard III. They really seem to know their stuff and think very carefully and deliberately about the musical components of each show. I didn’t understand half the jargon contained in either post which is pretty solid proof of that.

Aiming High: the Richard III Requiem Mass

Judgment Day: RICHARD III The Musical?

I was really excited by what I saw – the aforementioned guitar, the triple-duty gurney/throne/horse prop, the costume and stage sketches posted on the walls, the abundance of scythes and other torture instruments (including the thing that looked like it might be used for the extraction of a giant molar), the lovely singing, and, of course, the acting. Ann Arbor audiences, you’re certainly in for a treat!

Before I leave you with some photos from the Richard III rehearsals, I wanted to offer one last highlight. I learned from Laura that during the rehearsal day prior to my visit, the group had had an epic four hour long notes session. So, the bulk of what I was seeing was the company’s rehearsal of some of these notes. The scenes to be addressed were each prefaced in a humorous fashion by Mr. Hall…some personal favorites: “That went to rat sh*t yesterday. So let’s put a bandaid on that.” and “Could we look at the other massive car crash?”

(I hope he doesn’t mind that I was taking my own notes!).