Data as Playful: Sonification Specialist on superposition

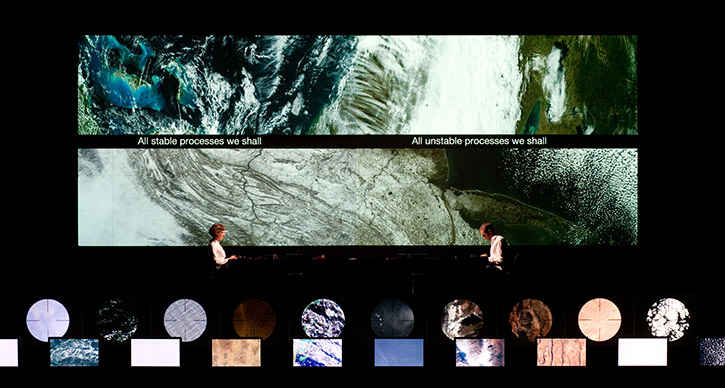

Scene from Ryoji Ikeda’s superposition, at Power Center October 31-November 1. Photo by Kazuo Fukunaga.

Robert Alexander is a sonification specialist working with the Solar and Heliospheric Research Group at the University of Michigan, where he is pursuing a PhD in Design Science. He is also collaborating with scientists at NASA Goddard, and using sonification to investigate the sun and the solar winds. We chatted with Robert about his fascinating work last season.

As it happens, Robert is also a big fan of the visual and sound artist Ryoji Ikeda, whose work superposition will be premiered at the MET in New York City immediately before it arrives in Ann Arbor on October 31 and November 1.

Robert chatted with us about what’s special in Ryoji Ikeda’s work, beautiful and playful data, and lion roars in the universe.

UMS: What inspires you about Ryoji Ikeda’s work? What in Ryoji Ikeda’s work influences the way you think about your own work with data sonification?

Robert: Ryoji’s work directly addresses the aesthetics of data. Within Ryoji’s work, we’re not only exploring data as beautiful but also data as playful. Data as immersive. Data as illusory.

He inspires me to think about how I represent scientific data sets. His work conjures the scientific and the precise and plays with these notions of accuracy, and he is very much playing quite often. As a data sonification specialist, I’m aware that I can also play with that balance between scientific representation and appealing directly to the notion of the “wow,” the sublime.

That’s what science can be. It can remind us of the beauty of this universe that we live in, the sublime experience of being alive. And sometimes the scientific representations can potentially sterilize that which may otherwise be enigmatic.

Performance trailer for superposition by Ryoji Ikeda:

UMS: You’ve seen Ryoji Ikeda perform multiple times. Can you tell us about one of those experiences?

Robert Alexander: One initial experience was at the International Conference of Auditory Display in Washington D.C. I had the chance to take in his work up close. He invited everyone up to sit on the stage, and I was sitting a few feet from the projection screen. His work lends itself so well to massive scale. It’s meant to completely absorbed, it’s meant to be immersive.

During this experience I was also captivated by his masterful ability to direct attention. As a composer or film producer, you’re often holding the audience’s attention almost like a tiny baby bird in your hand. You’re cradling the audience’s attention, and if you jar them, then that’s going to pull them out of the experience, but if you don’t provide enough stimulus, they get bored.

I was amazed at Ryoji’s ability to craft an experience such that I never felt pulled out of it. I was continuously pulled deeper into the work, I was continuously searching for deeper levels of meaning.

Spektra by Ryoji Ikeda:

UMS: How would you describe this work to someone who’s not familiar with it, someone who’s never had an experience like this?

Robert: I would probably pull out my phone and put the flash on the strobe function, point it directly at their face, and begin beeping at them [Laughs] I would say that’s about as close as I could get.

One perspective or take that might help someone new to the work is light. So, let’s say we go camping, and when we get there, we turn on our headlamp in the tent. Now we have minimal control of our environment, and yet we still feel that we have an element of modernity, so long as we are able to bring light to the space, even in its most rudimentary form.

When you think about representations of “the future,” be it eastern or western, many of them are ripe with dazzling displays of light, holographic representations.

When you think about Ryoji Ikeda’s work, let your eyes glaze for a moment, and what you’re witnessing is essentially a dance of light. He’s playing with light sculpture quite often, like in his work Spectra in London. He is both invoking this vision of the future, and yet working with just a single, minimal column of light. To truly appreciate this work you need to experience it, to stand beneath the pillar of light that he shot into the sky in this case.

And so, it’s fascinating how he goes about playing with light, but also sound. The auditory tapestry that he weaves, it vibrates with these simple minimal waveforms. We’re not used to the high frequency sounds in his work without those types of sounds signifying something important. We’re used to these beeps signifying a tele-type or a print out or a digital display, and the precision of these sounds coupled with the visual conjures this deeply synesthetic experience.

It’s absolutely hypnotic. I think that’s the way it’s meant to be experienced, as a complete sensory immersion.

UMS: We’re excited to be immersed! We also want to know about your work. What projects are you working on now? Do you have any updates for us since we last chatted last season?

Robert: I am still working very closely with a number of scientists at the NASA Goddard Spaceflight Center. Just recently, we published a case study titled “The Bird’s Ear View of Space Physics.” “The bird ear’s view” is a notion that we’ve used to describe what listening to data can provide. For example, when you listen to a data stream that’s been collected via satellite, you can hear minute fluctuations in something like the solar magnetic field. When you convert that to sound, given the rate of sound file playback, 44,100 data samples per second, we can hear the evolution of this data set across multiple days of real-time recording in just several second of listening, which is rather incredible.

In this case study, we worked closely with a single research scientist. First we introduced this scientist to these techniques of listening to data, and then we tracked how these techniques were integrated into his workflow, the types of observations that were made through listening, and how those observations led to additional formal investigations through visual analysis and through statistical analysis. And so this paper is great in that it covers the complete process for someone who is first introduced to this technique and then ultimately uses it to extract new knowledge from data sets.

Also, there are now many terms in the space research sciences, particularly helio-physics, terms such as “chorus,” “hiss,” “tweets,” “lion roars,” terms for physical phenomena, that have roots within auditory observations. For example, “whistlers” which are essentially results of lightning strikes that can be heard in very low frequency on radio waves, can be heard as this descending whistling sound, so the term “whistler” is now the default nomenclature for this phenomenon. It originally came about through just listening to the data, it’s an acoustic description. And then there are “lion roars.” Again, researchers were listening to a data set and they heard kind of a low “Grr” sound, like a low roar of a lion an the Serengeti [laughs], and that term has now stuck. It’s been really fascinating to work with research scientists, to play them some of their data sets and actually see the epiphany moment as their gears turn, and they say, “Aha!, that’s why we call it a ‘lion roar.’” [Laughs]

UMS: This all must be incredibly rewarding for you, to see your work receive this kind of support?

Robert: It’s been unbelievably rewarding to work alongside these research scientists and some of the brightest minds in the world and to be able to help provide a fresh perspective to these data sets, and also to provide them with the knowledge and infrastructure to apply these technique on their own. And that’s ultimately the goal, to enable the scientific community at large to adopt the practice of listening. It has been and continues to be an incredible experience.

Interested in learning more? See Ryoji Ikeda in Ann Arbor as part of the Penny Stamps Lecture Series and also the Saturday Morning Physics Series. Details on ums.org.