An Ode to Magical Thinking

Editor’s note: Budapest Festival Orchestra performs Beethoven’s 9th Symphony on February 10, 2017. In this inaugural post for UMS, Doyle Armbrust, a Chicago-based violist and member of the Spektral Quartet and Ensemble Dal Niente, proposes something drastic with respect to Beethoven’s 9th.

Maybe we need to try something else. Something drastic.

Since the presidential election, I don’t know how it is over in your silo, but in my silo I can’t seem to drown out the partisan squabble bleeding in from the outside. Binge watching Netflix has lost its opioid effect and dinner with friends seems to inevitably funnel toward one topic. Engaging isn’t working and neither is disengaging. It might take a miracle for us to step out of our respective trenches.

Hang on to that thought for a second.

My two-year-old can sing the “Ode to Joy.” I mean, he’s not all, “Freude, schöner Götterfunken…,” or anything, but he’s solid on the melody because Beethoven, at the apex of his genius, throws down a fully scalar melody to deliver perhaps his most poignant message to his generation (in Europe, anyway) and to all future generations (of the classical persuasion). And because there’s an incredible Muppets sketch of Beaker multi-tracking the tune before characteristically electrocuting himself.

What is the message? It certainly can’t be reduced to “Come on, let’s all get happy.” Joy, says Beethoven…well, Friedrich Schiller… “Your magics join again what custom strictly divided.” These flags, these gods, these bumper stickers — their divisiveness dissolves at the arrival of this splendid Daughter of Elysium (a.k.a. Joy). And then the clincher:

“Every man becomes a brother, where thy gentle wings abide.”

Let that sink in for a moment. Consider the cable news pundit that makes you want to Clorox your ears when you hear them sermonize. Then consider a world in which you greet each other like one of those dog-seeing-its-enlisted-owner-after-a-tour-of-duty videos. It sounds absurd, but what, other than something radical, do we have left to try at this point?

Having waited a full three movements before introducing the chorus, Beethoven dishes us a snippet of each before the bass soloist admonishes, “O friends, not these sounds…” The creation of life from the primordial ooze that is the “Allegro ma non troppo,” the haymaker of the “Molto vivace,” and the soothing allure of the “Adagio molto e cantabile” are not enough. If we’re going to stop screaming at each other, stop twitching for our holsters — in the composer’s Vienna or in our own republic — it’s going to take “songs full of joy.” Beethoven is even going to do a Jefferson Bible number on Schiller’s poem, cutting out politically-charged lines like “Safety from the tyrant’s power” to make sure we don’t get distracted by politics from the humanist utopia he’s pitching.

It’s aspirational, for sure, but not so naïve, it turns out. In his stirring documentary, Following the Ninth, filmmaker Kerry Candaele traces the symphony’s reverberations in situations far more desperate than ours. In Chile, General Pinochet locks up and tortures political dissidents — in this case, socialists whose elected government he had overthrown in a military coup — and how did wives and partners of these captives respond? By singing the “Ode to Joy” at the prison walls, infiltrating a dark despair with hope. Or what about the standoff at Tiananmen Square? There, the “An die Freude” was pumped like a pirate radio signal through loudspeakers to revitalize protesters in an impossible stalemate.

Beethoven’s score did not, of course, resolve these conflicts. What it achieved was to reveal hope where hope seemed inconceivable.

If sentient in 1989, your memories of the teardown of the Berlin Wall may revolve around David Hasselhoff singing at the Brandenburg Gate, sporting a particularly unfortunate scarf. You may also recall, though, a rousing performance of the Ninth by Leonard Bernstein in which the conductor would make the provocative switcheroo of “Freiheit” (“freedom”) for the original “Freude” (“joy”). It was the Cold War, so perhaps allowances must be made, but the visual of a city — literally split by polarized political ideologies — reclaiming its brotherhood is no less powerful for it.

If sentient in 1989, your memories of the teardown of the Berlin Wall may revolve around David Hasselhoff singing at the Brandenburg Gate, sporting a particularly unfortunate scarf. You may also recall, though, a rousing performance of the Ninth by Leonard Bernstein in which the conductor would make the provocative switcheroo of “Freiheit” (“freedom”) for the original “Freude” (“joy”). It was the Cold War, so perhaps allowances must be made, but the visual of a city — literally split by polarized political ideologies — reclaiming its brotherhood is no less powerful for it.

Now back to our shores. There was a fair amount of talk about “walls” in the recent election season, but the one that actually materialized is the one currently carving us up into teams for the world’s least amusing game of dodge ball. We can’t seem to count on mutual respect or zesty, fact-based debate any longer. It’s time for something unusual, absurd even. Something that will make you look over at that gentleman in the row in front of you, the one taking five full minutes to unwrap his butterscotch candy, and think affectionately, “My brother.” It’s going to take a leap of faith, and it’s going to require a killer soundtrack.

Maybe you’re thinking about going to see the Budapest Festival Orchestra because you read something in the New Yorker about the Budapest Festival Orchestra sounding pretty phenomenal with Richard Goode on the keys. Maybe Beethoven is your jam. Maybe your date is, like, the LeBron James of planning a night out. Whatever the case, since this is probably not your first time experiencing the Ninth Symphony, may I suggest that if you go, you consider Beethoven’s 9 beyond its entertainment value.

What if we choose to buy into Beethoven’s magical thinking — that there is a joy so profound that it might just bring us back together? You know, in the spirit of trying something drastic.

This post is written by Doyle Armbrust, a Chicago-based violist and member of the Spektral Quartet and Ensemble Dal Niente. He is a contributing writer for WQXR’s Q2 Music, Crain’s Chicago Business, Chicago Magazine, Chicago Tribune, and formerly, Time Out Chicago.

See Budapest Festival Orchestra on February 10, 2017.

Listen: Exploring Beethoven’s String Quartets with Stephen Whiting

Takács Quartet performs the complete Beethoven Quartet Cycle during the 2016-17 at UMS, a tour in conjunction with the release of Dusinberre’s new book Beethoven for a Later Age: The Journey of a String Quartet.

In conjunction with these performances, U-M Professor of Musicology Steven Whiting gives a series of lectures that explore Beethoven’s String Quartets. Recordings of these lectures will be available on this page.

Part 1:

Part 1 text excerpt. Listen above for full lecture.

Caution is not a word we ordinarily associate with Ludwig van Beethoven, yet he was cautious about engaging a genre associated by Viennese music lovers with his erstwhile teacher Joseph Haydn. Haydn had been the acknowledged master of the string quartet for decades. His works, above all others, had so raised the aesthetic stock of the genre that by 1800 the string quartet was regarded as the highest, noblest, most intellectual kind of chamber music. To paraphrase Goethe, a kind of idealized conversation between four equally intelligent and witty partners.

All through the 1790s, Beethoven studied model quartets by Haydn and Mozart after writing them out in score, because back then, quartets were only published in parts. Not until 1798 did he feel ready to enter the lists with his former master. He accepted a commission from the young Bohemian prince Lobkowitz for a half-dozen string quartets. Cheaper by the half-dozen. The same commission went out to Haydn. Vienna, you must know, invested in music the sort of cultural energy we invest in football. Is somebody keeping track of the score? Haydn was only able to complete the two quartets, later published as Opus 77. Beethoven’s first bundle of six was published as his Opus 18 in the summer of 1801. They served notice on the musical world that Beethoven was more than the latest hot piano virtuoso. He did not return to quartet writing until 1806, after he had revised his opera Leonore, a.k.a. Fidelio, unsuccessfully, as it turned out.

He set to work on a bundle of three quartets, apparently at the behest of Count Razumovsky, the Russian ambassador to the Habsburg court. I say apparently because the commission itself does no longer survive, nor is there any documentation of Razumovsky’s having asked Beethoven to work two or more Russian folk melodies into these quartets. It may have been Beethoven’s idea of a compliment. By common consensus, Opus 59 took the quartet out of the realm of private music-making by skilled amateurs and into the realm of public concertizing by professionals, because the music was just too darn hard for amateurs to play anymore. They are as massively scaled, in comparison with Opus 18, as the Eroica seems in comparison with the first two symphonies or Waldstein and Pathétique seem in comparison with earlier sonatas for piano solo.

Yet, Beethoven always frustrates listeners who grasp artistic development in terms of straight-line evolution. His next string quartet, composed during the French occupation of Vienna in summer 1809, and published as Opus 74, betrays far less symphonic ambition than Opus 59. It returns to the proportions of Haydn and some of the strategies. I am not the first to suspect that this quartet is Beethoven’s homage, and even eulogy, to Haydn, who died in May that year. You’ll hear it this weekend, and you’ll hear its even denser, more compact successor, the F minor Quartetto serioso, composed in 1810. For once, yes, the nickname derives from the composer. The high Opus number, 95, is explained by the delay in its publication until 1816. It is still a middle period work, albeit a thoroughly bewildering one. Then come the five quartets of Beethoven’s third, or late, period.

Continue listening to full lecture via video above.

Takács Quartet performs January 21-22, March 25-26, 2017 in Ann Arbor.

Artist Interview: Takács Quartet Violinist Ed Dusinberre

On October 6, 2016, Takács Quartet volinist Ed Dusinberre was interviewed by U-M Professor of Musicology Steve Whiting at Literati Bookstore in Ann Arbor.

Takács Quartet performs the complete Beethoven Quartet Cycle during the 2016-17 at UMS, a tour in conjunction with the release of Dusinberre’s new book Beethoven for a Later Age: The Journey of a String Quartet.

Takács Quartet performs October 8-9, 2016 and January 21-22, March 25-26, 2017 in Ann Arbor.

Why are Beethoven’s String Quartets widely regarded as his “greatest compositions”?

As a French horn performance major at the University of Michigan, I’ve been immersed in chamber music of all stripes, from classical duos to contemporary dectets. At U-M, my (brass and woodwind) colleagues and I strayed away from playing music of Beethoven, Haydn and Mozart in our chamber groups, while other (string) chamber groups played only that music. How can they play Beethoven’s music all the time?, I’d think to myself. Doesn’t it get boring? After four years of wondering, I’ve finally discovered that the answer to that question is “no”, and here’s why.

Beethoven was arguably the most critical figure in creating the movement from the classical era to the romantic era. Take a listen and you’ll see that his string quartets are easily the most intimate of his works. That’s because they involve only four voices, each with its own personality. For audience members, Beethoven’s string quartets are a keyhole to Beethoven’s genius during some of his most vulnerable times.

Beethoven took the string quartet to the next level, a level, perhaps, too high for many people of his time. While his predecessors like Mozart and Haydn wrote incredible string quartets as well, Beethoven had something new and exciting to offer in his string quartets. He added a new depth, variation, and complexity. Beethoven’s string quartets are often regarded as “characteristically unique.”

“They are not for you, but for a later age!” So wrote Ludwig van Beethoven about his Op. 59 quartets, which will be performed in Ann Arbor as part of a complete Beethoven string quartet cycle by the Takács Quartet over six concerts (three weekends) in the 2016-17 season.

Beethoven’s quartets are divided into three periods: early, middle, and late. His early quartets, nos. 1-6, are said to be reminiscent of Haydn and Mozart. The first three (nos. 7-9) of his middle quartets (nos. 7-11) are nick-named the Razumovsky quartets, as Count Razumovsky commissioned them. Beethoven’s sad and dismal last few years of life are well-reflected in his late quartets, nos. 12-16. Take a listen to the beginning of nos. 12-15 and you’ll hear that each has a slow, chorale-like opening, not something we hear in the openings of Beethoven’s early and middle quartets.

As I’m writing this blog post, I’m listening to all of Beethoven’s string quartets. For me, what’s prominent in each is genuine emotion. There are also dynamic contrasts that are characteristic of Beethoven’s symphonies. Each of his string quartets sound almost like mini-operas.

Take a listen to the fourth movement of Beethoven’s Quartet in B-flat Major, no. 6 – op. 18. The first section is marked as “La Melancholia Adagio” (played at a melancholy, slow tempo) and within the same movement, the second section is marked “Allegretto quasi Allegro” (played at a quicker tempo in a lighter, more dance-like manner). Within just one movement of one of Beethoven’s quartets, we experience two polar opposite tempos, styles, and emotions.

Here’s a special challenge for you: Try listening to the Takacs Quartet’s recording of Quartet in B flat major – op. 130, movement 5 without shedding a tear. I will say that, as a brass player, sometimes I can’t stay engaged when listening to string music, but the musical genius and emotion that Beethoven poured into his string quartets is impossible for me to ignore.

But what else makes these quartets so impossible to ignore? And what else goes into making these quartets so highly regarded as Beethoven’s best works? The musicians that play them, of course!

How do today’s musicians do justice to Beethoven’s String Quartets?

In the TEDx Talk above, Edward Dusinberre, first violinist of the Takacs Quartet, says that the primary goal of the Takacs Quartet is to “try to communicate a very strong musical character.”

While Beethoven may give hints by writing “specific character instructions” (as Dusinberre calls them), it’s up to the musician to interpret those instructions. Dusinberre mentions that the quartet must work individually and as a group to discover what style works best in effectively communicating a specific character instruction written at the beginning of the piece. This can be done by changing the timbre, articulation, dynamics, tempo, and musical phrasing.

There are only four voices in a string quartet. So, there are only four musicians, which adds to the intimacy of Beethoven’s string quartets.

But passion is what fuels the performance of the Beethoven String Quartet cycle, the same passion that fuels Beethoven’s writing of the piece. Through style, passion and communication, Beethoven’s string quartets are kept alive today.

The Takacs Quartet has released several albums and recordings of high merit, but the albums that have received the most recognition are their Beethoven String Quartet albums. These albums (one of which was awarded the 2002 GRAMMY for best chamber music recording) have received numerous awards and are highly praised.

Edward Dusinberre’s book, Beethoven for a Later Age: Journey of a String Quartet gives readers insider information on the journey of the Takacs Quartet as well as the journey of Beethoven’s composing his string quartets.

So, the answer is “no.” Beethoven’s music does not get boring for string chamber musicians, because they have learned to enjoy the process of bringing his music to life. As a musician, I am privileged enough to be able to musically tell a story. Beethoven’s string quartets and the Takacs Quartet have taught me — a brass player! — that the key to successfully telling the story is to engage the audience by communicating with them through my musical styles and through my passion.

Ann Arbor audiences can expect to experience this artist-to-audience connection during the Takacs Quartet’s performances of the Beethoven String Quartet cycle with UMS for the 2016-2017 season. As Dusinberre said, “The performance can create an atmosphere on stage where the audience doesn’t feel inhibited [to express themselves]”, an atmosphere that the Takacs Quartet is sure to bring to Ann Arbor.

Last but not least: Pianist Sir András Schiff on Last Sonatas Project

Editor’s note: Pianist Sir András Schiff performs three concerts of the “The Last Sonatas” by Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert February 16-20, 2016. Below is his reflection on the project.

Photo: Sir András Schiff. Courtesy of the artist.

“Alle guten Dinge sind drei” — all good things are three, according to this German proverb that must have been well-known to Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert. Introducing their last three piano sonatas in three concerts — twelve works, twelve being a multiple of three — is a fascinating project that can demonstrate the connections, similarities and differences among these composers.

The sonata form

The sonata form is one of the greatest inventions in Western music, and it is inexhaustible. With our four masters of Viennese classicism it reached an unprecedented height that has never been equaled, let alone surpassed. Mozart and Beethoven were virtuoso pianists while Haydn and Schubert were not, although they both played splendidly (Schubert’s playing of his own Lieder had transported his listeners to higher spheres and brought tears to their eyes). The piano sonatas are central in their œuvres and through them we can study and observe the various stages of their development.

Lateness is relative, of course; Haydn (1733-1809) and Beethoven (1770-1827) lived long. Mozart (1756-1791) and Schubert (1797-1828) died tragically young. It’s the intensity of their lives that matters. In the final year of his life Schubert wrote the last three piano sonatas, the C Major string quintet, the song-cycle “Schwanengesang” and many other works. What more could we ask for? These last sonatas of our four composers are all works of maturity. Some of them – especially those of Haydn – are brilliant performance pieces; others (Beethoven, Schubert) are of a more intimate nature – it isalmost as if the listener were eavesdropping on a personal confession.

Lateness is relative

Both Beethoven and Schubert had worked on their final three sonatas simultaneously; they were meant to be triptychs. Similarly, Haydn’s three “London sonatas” — the only works in this series that weren’t written in Vienna — were inspired by the new sonorities and wider keyboard of the English fortepianos and belong definitely together. It would be in vain to look for a similar pattern in Mozart’s sonatas. For that let’s consider his last three symphonies — but his late music is astonishing for itsmasterful handling of counterpoint, its sense of form and proportion, its exquisite simplicity.

Let me end with a few personal thoughts. The last three Beethoven sonatas make a wonderful programme. They can beplayed together, preferably without a break. Some pianists like to perform the last three Schubert sonatas together. This, at least for me, is not a good idea. These works are enormous constructions, twice as long as those of Beethoven, and the emotional impact they create is overwhelming, almostunbearable. It is mainly for this reason that I am combining Beethoven and Schubert with Haydn and Mozart. They complement each other beautifully, in a perfect exchange of tension and release. Haydn’s originality and boldness never fail to astonish us. Who else would have dared to place an E Major movement into the middle of an E-flat Major sonata? His wonderful sense of humour and Mozart’s graceful elegance may lighten the tensions created by Beethoven’s transcendental metaphysics and Schubert’s spellbinding visions.

Great music is always greater than its performance, as Arthur Schnabel wisely said. It is never easy to listen to, but it’s well worth the effort.

Pianist Sir András Schiff performs three concerts of the “The Last Sonatas” by Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert February 16-20, 2016.

Are there artists whose “late” creativity you admire? Discuss in the comments below.

The Audio-Biography Of The String Quartet

Photo: Elias String Quartet. Photo by Benjamin Ealovega.

The program the Elias String Quartet will share in its UMS debut on March 18 is like a sonic timeline of Classical Music’s most important genres, the string quartet. The three works the group will perform – Beethoven’s String Quartet in E minor, op. 59, no. 2., Debussy’s String Quartet, and György Kurtág’s Officium Breve – fit together like a veritable textbook on how the string quartet was established, codified, and subsequently transformed from the nineteenth century through the 1980s. It is extremely unusual, and very exciting, to have so succinct and comprehensive a portrayal of music history available on a single concert program.

Of course, this history begins with Beethoven, whose “middle” period works, such as the op. 59 quartets, represent his great turning point from an extremely skilled and gifted Classical composer, to the daring and freely minded Romantic hero music lovers glorify today. Beethoven’s metamorphosis was extremely precipitous to the history of Classical Music in the nineteenth century, and the String Quartet in E Minor, op. 59, no. 2 is certainly part of this legacy. This specific work contains numerous instances of Beethoven’s personality infecting the music’s form and affect; for example, in a likely allusion to the impolite Russian count who commissioned the set this quartet is part of, the work’s scherzo movement features an indelicately harmonized melody that was popular in Russia.

In light of the nearly invincible grip Beethoven’s influence had on nineteenth century composers, it is reasonable to think Debussy considered the German’s quartets when he penned his own in 1893. With that said, Debussy’s String Quartet, like his other music, breaks Beethoven’s mold in a number of ways, most obviously in its exploitation of instrumental color (listen for the prominent pizzicato passages in the second movement!). However, we should not interpret Debussy’s innovations as dismissive – rather, he makes vital changes to a genre that was over a century old at the time, and the musical expressions he explores are echoed by other composers in the early twentieth century, such as Maurice Ravel and Leoš Janáček, among others.

If Debussy’s String Quartet upholds through modification the traditional character of the string quartet as a stand-alone art form, a work like Kurtág’s Officium Breve shows how composers at the end of the twentieth century sought to more totally liberate this ensemble from its longstanding heritage. Officium Breve is starkly different from the other two works on the program – it is made up of fifteen short movements and is populated by constantly-shifting sounds and textures that represent extremely terse expressions on the part of the composer. Ranging from violent explosions of sound to tender periods of quietude, this work is enormously vibrant and deeply captivating.

Despite the fact Officium Breve bears little salient resemblance to the heart of its genre’s tradition, Kurtág’s work echoes the philosophy conveyed in the quartets of Beethoven and Debussy: existing forms may, and should, be altered in the name of artistic expression and ego. Placing living composers in a linear context with widely performed and recognized historical composers helps us, as listeners, observe how recently written music relates to the traditions with which we are more familiar. Unlike ensembles that predominantly program music from the nineteenth or eighteenth centuries, the Elias String Quartet is inviting its audience to share in these connections and is giving us a chance to see how a hugely important genre in Classical Music has grown over its centuries-long life.

Interested in more? Read more Garrett Schumann’s writing on UMS Lobby.

UMS Playlist: Classical Music Old Friends from Communications Director Sara Billmann

This post is a part of a series of playlists curated by UMS staff, artists, and community. Check out more music here.

Photo: San Francisco Symphony, who’ll perform Mahler Symphony No. 7 at Hill Auditorium on November 13, 2014.

I grew up in a small town in Wisconsin and studied piano from age 5 and oboe from age 11 in a family where music was central. My mother was a piano teacher, taught vocal music in the public schools, and directed her church choir; my sister became a professional horn player and freelances in New York; and even my father, a middle school math teacher for over 35 years, participated by periodically singing in a local chorus and playing the baritone in a local German band.

Because of that background, I was constantly exposed to classical music, but there are some pieces that stand out as having made an incredible impression on me as a young musician from the time of middle school until early college. While my tastes have certainly evolved over the years, these are still my “old friends” that I love to revisit and never grow tired of.

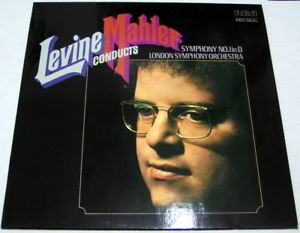

Mahler’s Symphony No. 1: I fell in love with this piece in 7th or 8th grade and can remember being home alone, turning out all of the lights, and lighting candles to listen to an early James Levine recording in a complete solitude. Mahler could take me to a place of incredible peace, only to be interrupted by the bombastic beginning to the fourth movement, which always scared the bejeezus out of me. To this day, I’m still a pushover for Mahler and the emotional range that his symphonic and vocal works explore.

Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 2: As an oboe player, I loved playing along with the record of Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 2. It’s such a joyful piece, fun to play, but also fun to listen to. My sister would occasionally play along with me, adapting the trumpet part for horn.

Beethoven Symphony No. 9: I played this work in high school with my local orchestra (with my sister also in the orchestra and my dad in the chorus). Being immersed in the sound of full orchestra plus chorus all on one stage was a remarkable experience for a young musician.

Tchaikovsky’s Capriccio Italien: While seemingly not performed very often these days, this is one of the first classical music pieces that I can remember falling in love with, probably in about 5th or 6th grade. If I remember correctly, we had an LP that included Capriccio Italien, Marche Slave, and 1812 Overture, but it was always Capriccio Italien that I returned to time and again.

Dvorák’s “New World” Symphony: Dvorák’s works are readily accessible and easy to listen to, but certainly not “easy listening.” A recent New York Times article talked about how Dvorák ended up in Iowa, where he wrote this symphony.

Schubert: When I left Wisconsin to move to Ann Arbor to attend the University of Michigan, my sister (then a senior at the University of Wisconsin) made a couple of cassette tapes for me of some of her favorite pieces by Schubert, which I listened to constantly for several years. Among the highlights: Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau singing Die schöne Müllerin, the “Trout” Quintet and the Rondo in D Major for piano duo. Sadly, her tape ran out in the middle of the work, and it was years before I heard how it ended.

Shostakovich: Michael Gowing, the former UMS ticket office manager who retired over a decade ago, considered Shostakovich a “B movie composer,” but I always loved his works. While in college here at U-M, I heard Mariss Jansons conduct the Oslo Philharmonic in Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 7 with its Bolero-like theme, and it was an extraordinary event that began a lifelong appreciation for Shostakovich’s works. I still love listening to the string quartets (especially Nos. 7, 8, and 15), his piano quintet, and many of the symphonies. The Kirov Orchestra’s performance of his Symphony No. 13 several years ago left me in tears, completely shaken at the power of music.

Listen to various selections and recordings of Sara’s picks on Spotify:

What did you think about this playlist? Share your thoughts or song suggestions in the comments below.

Behind the Scenes with Takács Quartet

During the 2016-17 season, the Takács Quartet performs the complete cycle in only four venues worldwide, coinciding with the release of a book by Takács first violinist Edward Dusinberre, Beethoven for a Later Age: The Journey of a String Quartet. The book explores the inner life of a string quartet, melding music history and memoir as it explores the circumstances surrounding the composition of Beethoven’s quartets.

In 2013, we interviewed Dusinberre about putting together a performance program:

Last updated 4/29/2016.

Tracing the String Quartet

Photo: Takács Quartet performs. Photo courtesy of Frank Stewart /Savannah Music Festival via npr.org.

Like the Mass, Opera and the Symphony, music for String Quartet is one of the most enduring genres in Classical Music. Since the genre’s emergence at the end of the eighteenth century to the present, generation after generation of composers have found this grouping of a cello, viola and two violins, inexhaustibly fascinating. Although there are a few notable exceptions, nearly every composer from Haydn to the present day has used this genre as a place for growth, experimentation and, above all, individual expression. Armed with its deceptively simple instrumentation, the String Quartet is capable of achieving an enormous range of textures, colors and moods, a generous sampling of which will be on tap at the April 12 performance by the world-renowned Takács Quartet.

The evening’s program begins with a representative work by the father of the String Quartet, Joseph Haydn, who, arguably, invented the genre out of necessity while working at the country estate of Baron Carl von Joseph Edler von Fürnberg. The ‘Sunrise’ Quartet displays the foundational form for String Quartets in the Classical Period, which was borrowed from symphonic music. The first and last movements are fast, and intervening are a slow second movement and a minuet, or, sometimes, a scherzo, which feature lighter fast music than the outer movements. Beethoven, who studied with Haydn, continued this formalism in his charming early quartets, but by they time we get to the Quartet no. 14 in c-sharp Minor, we encounter a work that is much longer and more formally diverse than its predecessors in the genre.

Dating from the final period in Beethoven’s life, the Quartet no. 14 is a leviathan and explosive gesture of Romanticism. Although this might seem hard to believe to a contemporary audience, most of Beethoven’s late works, including this quartet, were considered wildly and undesirably avant-garde. The Quartet no. 14 breaks the rules by possessing an unprecedented structural circularity, which means the audience should consider the piece as one large musical idea, instead of a series of smaller, separate gestures grouped together under one title. This continuity is built into the performance of the Quartet no. 14, because its seven movements are played without breaks between them.

Benjamin Britten

If Beethoven’s Quartet no. 14 represents the genre’s ability to portray a composer’s idiosyncrasy, and Haydn’s ‘Sunrise’ Quartet represents String Quartet music’s formal origins, then Benjamin Britten’s String Quartet no. 3 in G major, proffers one example of how later composers balanced these seminal elements. The work uses a broad range of textures and colors, which harkens to the diverse material of the Beethoven, though String Quartet no. 3’s five movements are decidedly unrelated, which is more in tune with Haydn’s Classical Period quartets. Britten died two weeks before the String Quartet no. 3 was premiered, but the piece is not a personal requiem, despite its many haunting and beautiful passages. Nevertheless, the work is a culminating example of Britten’s music, not to mention more modern composers’ contributions to the long line of works written for String Quartet.

Garrett Schumann is a regular contributor to UMS Lobby. Read his other commentary.

UMS Choral Union music director Jerry Blackstone with Beethoven

The UMS Choral Union took the stage this weekend in Detroit for a performance of Beethoven’s 9th with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra! Here’s UMS Choral Union music director Jerry Blackstone with Ludwig himself backstage.

Renegade Series will shake up your mud months

Some renegades: 1. Einstein on the Beach and 2. Random Dance.

A friend from Minneapolis was visiting earlier this summer, and we got to talking about the dreaded “mud months” up here in the icy north—February, March, alas, even April. Our friend mentioned that she’d spent a week in Arizona last February, but when I said I envied her, she shook her head. “Actually,” she said, “I cut my trip short. I couldn’t wait to get back.”

“What made you do that?”

The cultural life, she said. “There’s no cultural life down there.”

With apologies to the Heard Museum and Ballet Arizona, I think she’s got a point. And I’ve promised myself that this year, no matter how bad it gets, I’m not going to complain when it’s mid-March and I’m shoveling snow for the third time in a week, because the cultural offerings in Ann Arbor more than compensate. (Of course nothing about winter seems bad right now, so long as there are no mosquitoes.)

I’m actually looking forward to the mud months of 2012, because that’s when UMS—in what’s either a brilliant move or a potentially ruinous gesture of faith in the weather gods—is presenting its Renegade series. For me it’s the most tantalizing thing on offer this season, and I’ll be tracking it here on the Lobby, hoping to answer some of the questions I’ve long had about the process of art and art-making, and what makes some artists true outposts of genius and others mere followers. The series starts in January with a reconstruction of the 1976 opera Einstein on the Beach and winds up in late March with the San Francisco Symphony’s “American Mavericks” series, and in between covers a wide and intriguing arc of genres and eras. Beethoven, Gesualdo, Robert Lepage, Jessye Norman, Meredith Monk, Robert Wilson, Philip Glass—they’re all part of it, and they’ll all be here, in spirit or person, as we hunker down under Michigan’s gray skies and count the days until the crocuses bloom.

Because he has as much to do with the evolution of this series as anyone on the planet, I’m starting my personal Renegade “journey” with UMS Programming Director Michael Kondziolka:

LS: What’s the genesis of the Renegade series?

MK: I’ve been having a conversation for 10 years about Einstein on the Beach. And I was also having a conversation with the San Francisco Symphony about a remount of their American Mavericks festival—the first one they did was 10 years ago, in San Francisco. Both of these conversations were long-term and ongoing. And there was a moment when I realized, “Huh! It appears that both of these projects are going to land in the same season.” And when I realized that, I started thinking about the commonalities.

The American Mavericks festival is really all about Michael Tilson Thomas’s vision for a certain kind of American sensibility and “mavericky-ness” when it comes to orchestral music composition—what it means to be American, and what it means to be an innovator and an experimenter. And how can that not in some way relate to Einstein on the Beach, which is, of course, an American work of music, theater, or opera that very much embodied those same ideas of risk-taking, innovation, scale, in creating something really new.

That, strangely enough, collided with another moment that I had last season, where I’m sitting there listening to Pierre Boulez talk about his life, his ruminations on the 20th century, and his role in that. And a student asked a really wonderful question about what the new electronically based media means for music and composition. And Boulez said, “Je ne suis pas un prophète.” “I’m not a prophet. ” And he started to expound on artistic works that are truly important, that are game-changers—works we could never, ever have possibly anticipated, and once we’ve experienced them, could never imagine living without. This was his definition for something that’s truly important.

And I guess it was that statement from such an important intellectual, about art and culture, and these two projects that were long-term conversations, coming together and forming the possibility of a thread of performances devoted to this idea of work that really has changed the direction of the form.

LS: I like the term “game-changers.”

MK: It also felt very zeitgeisty to me. That these things came together at a time when our popular discourse, and our popular political discourse, is just polluted with vocabulary about innovation. “Innovating our way out of the difficulties that we face today.” “Being a maverick.” “I’m the real maverick.” All of this bullsh!t that’s kind of like wallpaper, but there’s no real there there. And of course there are lots of examples of real mavericks, of people who are really innovating, but it also seems kind of … cheap. We’re cheapening the meaning of some of these ideas, of what it means to be a real change-agent.

LS: Why “renegade”?

MK: Ultimately we wanted to choose a word that hasn’t been overused, a word that maybe made people feel both a little bit curious and a little bit uncomfortable. I like the word, because it toggles between the artists, their artistic output, and the audience. What does it mean if you’re an audience member who chooses to go to these sorts of events? Are you a little bit of a renegade? Are you taking a risk? How do you feel about taking that risk, and what do you get out of taking that risk? As consumers of the arts—as listeners and observers—it is the moments when we take risks, or step into something that we have no idea what it is, and are completely bowled over and changed, that matter. Period.

LS: In an ideal world, what do you hope audiences might take away from this?

MK: In a dream world, I want the takeaway to be something really simple. I want people to leave the experience with some sense of that quality of innovation, or change-agency, or specialness, that defines the work as part of this series.

LS: You start with a bang—Einstein on the Beach—and end with another bang, the San Francisco Symphony’s Mavericks series. So how did you decide to flesh out the middle?

MK: How did I want to fill in that time between those two bookends (which is what we’re calling them)? The one thing that was really important to me was that it not focus only on work of the last 50 years. I didn’t want this to feel like a quote-unquote contemporary music series. I wanted to tell a much larger story about moments of extreme change. So I asked Peter Phillips of the Tallis Scholars to put together a Renaissance mavericks program. And we’ve included the Hagen String Quartet’s all-Beethoven concert as a wonderful way of creating an opportunity to understand how Beethoven really changed classical music aesthetics. That’s an obvious concert to include in a series like this. I think Beethoven’s the ultimate maverick.

LS: Beyond just having an interesting cultural experience, and coming away saying, “Wow, I was there for that,” does a series like this have the potential to change our culture by changing the audience? In the best of all possible worlds, how might this shake people up? What might they get from this that goes beyond just the bragging rights, and the curiosity factor?

MK: Obviously, if entering into an unexpected experience opens those kinds of ideas up in an audience member’s mind, that for me would be a very important, possibly transformative takeaway—because we’re reminded, ultimately, of the intrinsic value of the arts and not just the instrumental value of the arts. Now: is that any different from the experience I want people to have when they go to the all-Brahms program with the Chicago Symphony? Probably not.

LS: It does seem that when you’re packaging this as “renegade,” you’re focusing on the process of creating this art, rather than just, “Let’s go hear these great works that are part of the canon.” I mean, how did they get to be part of the canon in the first place?

MK: Exactly.

LS: And what does that mean for us, and how and where we need to move our culture forward?

MK: That’s right. I think you’re right. I also think that accessing a lot of work really ultimately has everything to do with giving yourself permission. Einstein on the Beach, for example, is a five-plus hour work without an intermission …

* * *

In my next post: More from Michael Kondziolka on Einstein on the Beach.

What do you think? Do renegade works fill audiences with renegade spirit? Have you attended a ‘renegade’ work?