Interview: Emmanuel Pahud, flute

A star flutist only comes around once or twice in a generation — and it’s fair to say that this generation’s strongest candidate is the Swiss-born Emmanuel Pahud. We sat down with the Berlin Philharmonic principal flutist last year about his upcoming Ann Arbor recital.

Emmanuel Pahud performs in Ann Arbor on Wednesday, February 14, 2018.

Artist Interview: Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, Kenny Rampton

University of Michigan student Teagan Faran spent Summer 2016 with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra as part of the UMS 21st Century Artist Internship program. The interview below is with Kenny Rampton, trumpet with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra. The group returns to Ann Arbor with pianist Chick Corea on March 31, 2018.

Photo: Left to right, Wynton Marsalis, Ryan Kisor, Kenny Rampton, and Marcus Printup. Photo by Frank Stewart.

Teagan Faran: How long have you been working with Jazz Lincoln Center?

Kenny Rampton: I joined full time in June 2010. I’ve been kind of in and out as a sub more or less since the 90s. I’ve known Wynton for a long time and had also been in and out of the band before it was an established, regular band. In the beginning, it was kind of a mix with players – maybe nine trumpet players – and Wynton would call upon us, and we’d play depending on who’s available. We were all freelancing with different bands and then eventually became a set band.

TF: What about the organization attracted you to join? What makes JLCO stand out?

KR: First and foremost is the educational aspect of it. I grew up in Las Vegas, and when I was a little kid, my parents were involved in music education. My mom actually fought the school district in Clark County, Nevada where I grew up because they were trying to fire all the music teachers in elementary schools. My mom was against that. She fought the school district to make sure that there was music education in the schools from elementary school on. My dad was a percussionist, and he played in all the schools for the kids. They were both about music education and from the time I was born, music education has been part of my life.

Coming here to New York, I was touring with Ray Charles and then with Mingus Band and Jimmy McGriff. They were all great gigs, but what makes JLCO and this organization stand out more than anything else is the education. We do a lot. I just finished a master class in Poland. I did one in Cuba and others all throughout South America. We do education all over the world. To me, that’s extremely important. For me, it’s full circle. It’s continuing my parents’ work.

The other thing is that it’s just a really good band. I like playing with people who are better than me. Playing in this trumpet session with Ryan Kisor, Marcus Printup and Wynton. It’s just inspiring.

TF: Do you feel like it’s more beneficial to be with the same people in a band and get to know them?

KR: With this band, yes. I’ve done other gigs, like Broadway shows where you’re playing the same music every night, the exact same way. That can be grueling. One thing about this band is that it’s the same people, but we’re always doing new music. Normally, most of the concerts we do are brand new arrangements for that specific concert.

We’re always challenging each other with the arrangements in the band, so that keeps it interesting and helps to maintain an environment where we’re all continuously growing. The better you get, the deeper you get into it, the more you realize there’s always room for improvement. No matter how good you get, there’s always another level to get to. It’s great.

TF: As a musician and arts educator, what do you think is different about what you’re trying to accomplish nowadays, as opposed to 10 or 15 years ago?

KR: For me personally, I’m more conscious of what it is I’m trying to do. I have more direction. Before, when I first got into playing music, it was something I was good at. I was drawn to music because of that, and it was about my ego. Then, I started to become aware that music is actually not about me. It’s actually my purpose. I consider music to be a spirit that touches people and can make a difference. I started to become more aware of that and realized that when we play music, it affects people’s mood. People can come out of a gig feeling good or feeling bad. We can consciously go into it, wanting to make a difference in somebody else and how they feel.

My purpose changed after realizing this. That’s the biggest difference for me in the last decade, as I started to see music as my way of making a positive difference on the planet and life. I started seeing music as something that can really change a life and make a real difference. You realize that music can touch the heart, the spirit, and raise their vibration. Because that’s what music is, it’s a vibration. It becomes more than about me and having somebody to tell me how good I sound. It becomes a spiritual quest or a calling.

There’re so many great humanistic qualities to learning to play jazz music that we can teach students. Whether they become professional musicians or not isn’t the point, but they will become better people. You can’t help but become a better person when you have empathy and when you know how to negotiate and work with other people.

You might be in disagreement about something, but you still work together and you find a common ground, that’s what music teaches us. When we teach students, I always stress that understanding. That’s really what it’s about.

TF: What would you say to a student who’s on the fence about attending the concert?

KR: Why would somebody be on the fence about attending a concert to hear good music? To any student, I say check out everyone and any concert you can that can possibly open up doors and inside yourself. It’s not even necessarily about doors to meet players and network, there’s that. You meet people so you network, and the more opportunities you can have to meet people who are doing what it is that you want to do, the better for networking purposes.

Beyond that, you never know when somebody on that stage is going to play something extraordinary. As a student, you sit there in the audience and think, “Wow, I didn’t know that can be done on the saxophone.” It’s going to open up something that makes you want to practice and to be inspired.

Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra returns to Ann Arbor with Chick Corea on March 31, 2018.

Updated 6/2/2017

Artist Interview: Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, Vincent Gardner

Editor’s Note: University of Michigan student Teagan Faran spent several weeks with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra as part of the UMS 21st Century Artist Internship program. Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra is returning to Ann Arbor on March 4, 2017. The interview below is with Vincent Gardner, lead trombonist with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra.

Photo: Vincent Gardner with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra. Photo by Frank Stewart.

Teagan Faran: Could you tell us about your role at the JLCO?

Vincent Gardner: I’m the lead trombonist with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra. I’m also the director of the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra Youth Orchestra, and I’m the Swing University professor. I teach classes here on jazz history and different aspects of jazz history. I’ve been here about 16 years.

TF: What about Jazz at Lincoln Center attracted to you initially?

VG: I guess when I first joined the band, I was what I’m still now, just a trombone player, who just had to play with the best musicians possible – well, musicians that I like and get along with and enjoy making music with. Those are also the ones who would inspire me to get better playing.

That was the biggest draw for Jazz at Lincoln Center. It’s a great organization. It inspires me and allows me to contribute to it. More so than just being a trombone player in a band, that is the difference. Here I have a chance to be a lot more invested in everything that goes on.

TF: Is there anything else that you would say makes Jazz at Lincoln Center stand out?

VG: I’m encouraged to connect to every part of the music. I think it’s essential in jazz music that you are always connected to every part of the music, not just what you play on your instrument. They’ve taken that philosophy here and put it into an institution, and that’s the greatest thing. You get to be involved. You’re encouraged to be involved as much as you want to be.

TF: What suggestions would you have for other ensembles that want to integrate music into their community in the same way that Jazz at Lincoln Center has?

VG: I would imagine that just about every community has great musicians or somebody doing great things in music or in the arts. You have to embrace those people and bring that community together under the guise of an institution that embraces all of the people who are doing great things for the arts.

We are a very big and prominent institution here in the city. In a smaller city, if you want to start an institution, you wouldn’t necessarily expect it to be as big, but it could still be very influential. You have to find out who the movers and shakers are in the arts. Who are the people that are genuinely trying to advance the arts and arts education in your city. Find out who the greatest teachers are, most genuine and greatest teachers are. Find the most talented kids, always get around the most talent.

It’s kind of the same thing playing in this group, being around the most talent and being around people who are most motivated. Once you find those people in any situation, you’ll find that you have similar goals.

TF: As a performing artist and arts educator, what are the biggest challenges you feel you’re facing today?

VG: Well, they are the same challenges. They’re not different. The biggest challenge is making sure that the same information is being communicated in the best way. For example, let’s talk about music instruction. The way they teach jazz music is not standardized. You have people who have the title of jazz educator or jazz band director, who are teaching complete misinformation to their students. Their bands don’t sound as good as a result, but because there is no other local standard or no standardized way of teaching it, they think it sounds fine. The community thinks it sounds fine because the community doesn’t really know the music anymore.

That’s one of the biggest things. You don’t find that in classical music, you don’t find that in other music. It’s only in jazz music, which is the music of this country, that you find such disparity in the level of teaching. That’s the thing I see the most in my teaching and in my traveling. It’s very hard at this point to standardize it and make sure it’s all on a high level.

TF: What would you say to a student who’s on the fence about attending a JLCO concert?

VG: I’d say, “It won’t hurt.” It definitely won’t hurt anything, and you’re going to hear a band full of great musicians, playing genuine music that has the ability to connect with people. It’s not something that’s marketed towards any one person or was ever meant to be reserved for any one group of people. That’s inherent in the sound of Swing. It can’t be played in a way that restricts it from anybody. It’s not possible to do that.

I would say that you will come, and you will find something in there that does connect with you. It could be different for every person, but it will be there because it’s inherent in music. It’s meant to connect with people. That’s the thing I would tell somebody: Take a chance. Everyone should give jazz a chance. Everyone should go to jazz concerts a few times a year.

Go to reconnect with that American ideal put into music – what’s great about society, about being American, and about people from anywhere.

Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra returns to Ann Arbor on March 4, 2017.

Artist Interview: Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, Carlos Henriquez

Editor’s Note: University of Michigan student Teagan Faran spent several weeks with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra as part of the UMS 21st Century Artist Internship program. Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra is returning to Ann Arbor on March 4, 2017. The interview below is with Carlos Henriquez, bassist with Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra.

Photo: Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Carlos Henriquez on bass. Courtesy of the artist.

Teagan Faran: How long have you been with Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra?

Carlos Henriquez: About 15 years now.

TF: What about the organization attracted you to it?

CH: I was 13 when I met Wynton [Marsalis] through the Music Advancement Program at Juilliard. I just started hanging around him and going to some of the rehearsals. I started playing at the rehearsals, too, and then, just hanging. One thing led to another.

TF: What about Jazz Lincoln Center makes it stand out from other musical organizations to you?

CH: It’s the educational portion of it, the outreach program. JLCO is always looking for talent but also supporting other musical programs.

TF: What would you suggest to other ensembles that want to be a part of the community the way that Jazz Lincoln Center is in Manhattan?

CH: Well, I think they can look at the model for educational programming at JLCO. Many shows produced by JLCO start on a very small scale. It’s good to involve your community like we’ve done in New York and just find people who are really into the arts

TF: What are some of the challenges you think you face as a performer nowadays?

CH: The biggest challenge is the times. Times are changing, so what’s happening is that people are either not informed or their knowledge of music is very limited. People are more informed about pop culture than other culture. It’s complicated.

TF: What is the performance dynamic like in Ann Arbor?

CH: It’s always been an educational environment. Every time I’ve been there, it’s always working with students and the students seeing us play. That part is so great. Ann Arbor is also not far from Detroit, and there’re so many great Jazz musicians who come through that region. Every time we go, we usually meet great musicians and even play with them.

Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra returns to Ann Arbor on March 4, 2017.

Artist Interview: Takács Quartet Violinist Ed Dusinberre

On October 6, 2016, Takács Quartet volinist Ed Dusinberre was interviewed by U-M Professor of Musicology Steve Whiting at Literati Bookstore in Ann Arbor.

Takács Quartet performs the complete Beethoven Quartet Cycle during the 2016-17 at UMS, a tour in conjunction with the release of Dusinberre’s new book Beethoven for a Later Age: The Journey of a String Quartet.

Takács Quartet performs October 8-9, 2016 and January 21-22, March 25-26, 2017 in Ann Arbor.

Behind the Scenes with Yuja Wang

Piano sensation Yuja Wang (left) performs with acclaimed violinist Leonidas Kavakos (right) on November 23, 2014. Photos by Ian Douglas and Marco Borggreve.

We’re very excited for Yuja Wang’s return to Ann Arbor this November, when she’ll perform with the acclaimed Greek violinist Leonidas Kavakos. Yuja last performed in Ann Arbor in a solo recital in 2011, when we had the chance to ask her a few questions.

UMS: You’re often described as a young piano prodigy. How do you think your youth affects your performance?

Yuja Wang: If there is any effect, I think it’s unconscious or subconscious, but the pieces I learned when I was say, before 16, I would never forget, they just stick with you your whole life.

UMS: Can you talk a little about how you put together your programs? What’s your dream program?

YW: Programming is an art and I get inspired by the menus in Japanese restaurants. Variety and unity are key for me now.

UMS: What composer or work do you find most challenging to play? Do you view that as a good thing?

YW: I only play the works in public when I think I can handle it. Playing, perceiving, understanding, internalizing a work sometimes requires a lifetime, it changes when our point of view of life changes, it’s something that stays with your life, something that counts in the end.

UMS: What’s one piece of advice that you could pass on to other young aspiring musicians?

YW: Go with the flow, be creative, transcend to something more cosmic.

Did you attend Yuja Wang’s previous performances in Ann Arbor? Share your thoughts or experiences in the comments below.

Artist Interview: Ryoji Ikeda, creator of superposition

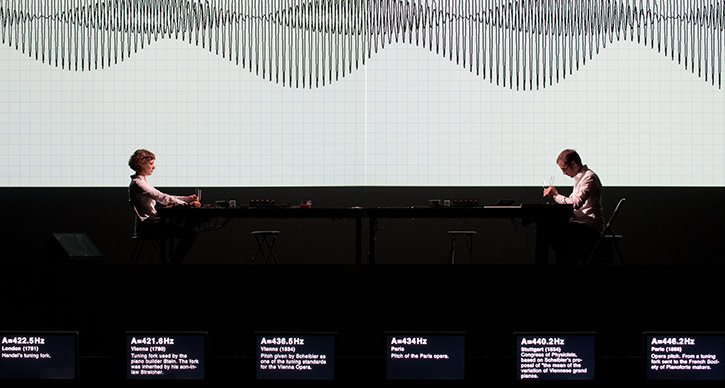

Photo: Moment in superposition. Photo by Kazuo Fukunaga.

superposition is a performance created by visual and sound artist Ryoji Ikeda. Inspired by the mathematical notions of quantum mechanics, Ikeda employs a spectacular combination of synchronized video screens, real-time content feeds, digital sound sculptures, and for the first time in Ikeda’s work, human performers.

The work will be premiered at the MET in New York City immediately before it arrives in Ann Arbor on October 31 and November 1.The interview excerpted below is between Ryoji Ikeda and Peter Weibel, and was recorded at ZKM Karlsruhe on July 31, 2012 by Manuel Weber and transcribed by Wolfgang Knapp.

Peter Weibel: First, thank you for the time and opportunity to speak about your work. My first question would be about title: superposition. Are you referring to the quantum mechanical idea or are you referring to the cinema, where you work with superpositions. What is the idea behind the title?

Ryoji Ikeda: I have never specified anything. How did you feel when you heard the word “superposition”? I am very curious about people’s can impressions when they hear “superposition.”

PW: Well, I would think of the wave function of Schrödinger, from quantum mechanics. Then I would think of the super-imposing of image on image, and then I would think of the observer who has a position superior to anything else.

RI: Because you are a very intellectual person. When you hear the word superposition, you are inspired. But, for example, my mother just thinks, “Super! Position!” The word has a very wide spectrum of meanings, and I think that’s good. People can get many meanings. And of course, I am obsessed by that quantum mechanical meaning. And also, the other superposition principle, the fundamental principle of physics. For example, the harmonics that superpose and that make our voice and sound.

superposition performance trailer:

PW: So you are also thinking of musical notations? Of the superimposition of frequencies?

RI: Yes, exactly. But the core topic for me is the quantum mechanical meaning, the fundamental characteristic of quantum physics.

PW: When did you become interested in the quantum nature of reality? And why?

RI: I read some books when I was a student. Of course, it was really difficult and pretty counter-intuitive. But it stunned me to discover quantum mechanics. After that, I became an artist, but it was absolutely impossible to describe quantum mechanics for my art. So, I just make a piece of art. It’s a performing art piece, which never explains quantum mechanics. It is rather inspired by quantum mechanics. Some of the expressions are scientifically correct. I use lots of data sets from NASA and so on, but the construction, the composition is very intuitive because I am an artist. So, it’s hybrid.

PW: I see. I can imagine that when you have to make a decision between the classical world view — that means causality and mechanics — and quantum mechanics, I think that, as an artist, the idea of uncertainty or of many different possible worlds is more attractive. I think all these possible worlds give us — as artists — more freedom.

The people who help you working on the superposition performance – your assistants; are they programmers? Musicians? What is their profession?

RI: They are basically programmers. And architects and all kinds of artists. They are very young, in their twenties. They can program almost in every language. Super.

PW: I have a question for you as an artist. How do you solve the following problem? Morton Feldman, the wonderful American composer, said that music is structure. Normally it is time-based structure. But Feldman disliked most kind of music because it is a slave of time. Rhythm and beat – these things control the music. Time tells music what to do. But Feldman wanted to destroy this control. He wanted music that was not slave to time. How do you solve this problem? Can we create a music that is superior, music that destroys our structure of time?

RI: I really like most of Feldman’s music and his philosophy, but I can’t really follow him. And after John Cage and after that generation, you know, and the generation of computer and programming, my direction is super-precise, it is the direction on “control.”

PW: So, no chance experiments like Cage. Control instead of chance.

RI: I try to control randomness. This is a big counterpoint, the encounter of randomness and control. The contrast is more interesting. If you really control a millisecond, there are other possibilities, even if they are microscopic. You can’t perceive the change directly, but if you pay very close attention, the entire composition changes. So, I try to add randomness, and I like to see the counterpoint, the counterbalance.

PW: Schönberg in his book Style and Harmony stated that the composer’s challenge is to move from one note to the next. You don’t work with notes but with waves, continuous sine waves. A note is a discrete model. As an acoustic artist, how do you see this problem?

RI: Of course, I use sine waves, pure waves, but if you reduce the waveform to its function, this point is very, very tiny and is called the impulse. It is so short that when you listen to such a sample you don’t hear it. The point is what makes the acoustics. Sine waves are continuous, they have no direction. They never contribute to acoustics.

It’s the opposite of white noise, which is random. That’s a different thing, but I use lots of impulse, as you will hear. I’d never use one hundred speakers like [the composer] Stockhausen does. No. Mono! At the center of a church or some very large space, maybe just an impulse on a single mono speaker. That would make you feel the very acoustics spatially through some rich reverb created by that very short impulse.

PW: I see. The acoustics of a wave is a kind of point you…

RI: …you slice.

PW: Exactly.

RI: Any point.

PW: Brilliant idea. So I see that you are now investigating not only a new organisation of sounds but a new series of harmonies on a technical and mathematical basis.

RI: Yes. That is my basic research. This is not really the work of an artist but basic research for basic knowledge to find my language. To develop my alphabet and the grammar is my structure, my music. And I don’t want to use the normal alphabet.

Interested in learning more? See Ryoji Ikeda in Ann Arbor as part of the Penny Stamps Lecture Series and also the Saturday Morning Physics Series. Details on ums.org.

Artist Interview: Cuban Pianist Alfredo Rodríguez

Photo: Alfredo Rodríguez. Photo by Anna Webber.

Alfredo Rodríguez is a Cuban pianist and composer. He was born in Havana, Cuba, in 1985. With a well-known Cuban singer as his father, it is no wonder that he has been surrounded by music his entire life. He started studying at the Manuel Saumell Cuban Conservatory at the age of 7, and has been playing and creating music ever since.

Alfredo spent some time talking with us about his experiences in Cuba and in the United States, his thoughts about a musician’s life, and his upcoming work. He’ll perform in Ann Arbor on March 14, 2014 as part of a unique double-bill with Pedrito Martinez Group.

Annick Odom: We know that you’ve played in Ann Arbor and Detroit before, but we’re really excited to have you playing for the first time with UMS in March. Your work draws on jazz and Cuban music traditions. How do you balance these in your own music?

Alfredo Rodríguez: Well, I started as a part of his [my father’s] band when I was very young, about 13. We used to play popular music, music from the traditions of Cuba and his compositions as well. I combined that kind of performing, that kind of ambiance, with the classical school.

In Cuban music, there is a lot of improvisation, but I didn’t know much about improvisation in classical music at that time. My uncle gave me an album called The Köln Concert by Keith Jarrett [the legendary jazz pianist], and that got me into improvisation.

I was used to Cuban traditional music and classical composers like Johann Sebastian Bach, and also to Latin composers. After that CD though, I found the music of many of the pioneers of the be-bop era, a lot of different musicians, mostly from the United States. I was falling in love with the way those composers and instruments created music.

AO: We presented Keith Jarrett in 2000! What exactly about that recording drew you in so much? What made you so excited about improvisation?

AR: Well, my uncle gave me that CD with an idea in mind, because he was not very involved in piano music. He gave me that CD because he knew that I was very into that world. But I wasn’t expecting anything it. I just put it on. It was a great introduction for me because Keith Jarrett had that touch and that knowledge about classical music, and he shows a lot of those influences in his playing. It was a good introduction for me to improvisation and jazz music, too, of course.

AO: You said that you played a lot with your father while growing up and that you played a lot of popular music in Cuba. How would you say that you’ve individualized yourself from previous generations of musicians from Cuba?

AR: I guess I would say that [the musicians in my generation] are changing every day. We have different experiences every day. [My generation] grew up in a different situation than the generations before us in Cuba. We had different problems, different ways of living, [different] points of view. And of course those differences are the reasons that music changes too.

What I like to do with my music is to just express the present, just express how I am feeling, what I am going through in that exact moment. I guess what I am trying to say is that everybody always has something to say, and it is always different for everybody. And that kind of honesty is what I look for in terms of music, and in terms of living my life.

So it’s very simple for me, I just try to express who I am when I play my music and compose. I try and show my [Cuban] roots and also the transculturation that I have been living since I have been here in the United States.

AO: Do you find yourself playing any differently since you moved to the US or do you play pretty similarly to when you lived in Cuba?

AR: No, I’ve definitely changed. The United States is a different country with different culture, which has been a very positive process for me in terms of learning.

[Cuba] is an island, and due to the country’s political history we have been only around Cubans for more than 50 years. The culture that we have been creating for so many years is very unique and powerful because we are surrounded by Cubans, but at the same time, it’s contradictory because we haven’t had the opportunity to have confrontation and transculturation with different cultures.

I wanted to know different cultures and meet different people with different points of view so that I could incorporate all of that into myself and reflect it in my music.

AO: Let’s talk about your upcoming concert here in Ann Arbor. Who will be coming with you? What will you perform? Can you also talk a little bit about your upcoming album?

AR: Actually I am releasing my next album The Invasion Parade on March 4th, which is going to be very, very close to the concert [in Ann Arbor on March 14]. I am going to be featuring the same trio that I had for my album at the concert. We are featuring different artists, but the main trio that I perform with is Peter Slavov, a Bulgarian bass player, and Henry Cole, a drummer from Puerto Rico.

We are going to be performing the music on this upcoming album as well as music from the past. But to be honest, music is very natural and spontaneous for us, so we just like to play songs that will fit in the moment that we are living.

It’s difficult to say exactly what songs we’ll play or even what the music is going to sound like. I guess what I mean to say is that we have the message that we want to tell people: 70% of my music is improvisation, and the other part is rhythm. So it’s kind of unexpected, and in that way, we learn more from ourselves.

AO: You’re sharing the bill with Pedrito Martinez. Have you ever played with him before?

AR: It’s very funny because Pedrito is part of my album [The Invasion Parade], too. I love his playing! Pedrito is one of the musicians coming out of Cuba that I admire so much because of his incorporation of our culture into his vocals and percussion. And speaking of my album, it also features Esperenza Spalding, and horn players from Cuba and Puerto Rico. But yeah, speaking of Pedrito, we have a really, really close relationship in both in terms of music and friendship.

AO: It seems that you are already thinking a lot about the upcoming months, but where do you see your music going even further into the future?

AR: That is a good question. To be honest, I don’t think too much about the future. What I can share with you is something that I’ve been working on since the past, until today, which is creating music.

I am also currently writing a lot of music for the symphony. The premiere of my first symphonic work will be this year in November, and I will be performing one of my compositions with an orchestra at the Barcelona Jazz Festival. And I’m working on new music for my trio and my upcoming CDs.

I do it [compose music] because I just need it. It’s like water for me. If I am inspired, I write something. I’m just composing music, doing what I like to do. I feel very fortunate about that because I just have the opportunity to live from what I love to do, and I am very grateful for that.

Interested in more? Check out Alfredo’s new album or get tickets to his performance with Pedrito Martinez Group in Ann Arbor on March 14, 2014.

Artist Interview: Colin Stetson

Photo: Colin Stetson, who performs in Ann Arbor on April 14, 2018. Photo by Scott Irvine.

In January 2014, saxophonist Colin Stetson performed in Ann Arbor as part of a special week of Renegade performances also featuring performances by the Kronos Quartet. We’re looking back on our chat with Colin to get ready for his return to UMS on April 14, 2018 in Colin Stetson: Sorrow: A Reimagining of Górecki’s Third Symphony.

UMS: Your performances are a part of a “renegade” theme in our season, through which we explore artists and composers who “break the rules” in their own time. How do you feel about the term “renegade”?

Colin Stetson: I don’t think I particularly feel much about it actually. I don’t think about myself or this music in those terms at all.

UMS: How do you think about it?

CS: Well, I think that that terminology kind of implies a certain comparison between inspiration and performative processes of your music to other people’s processes and to the greater whole of music making, and I really don’t function that way when I’m making this music.

If there is any amount of boundary pushing or ground breaking, it’s really more of personal journey and a personal set of goals that I kind of outline for myself. And I’m constantly looking for new ones, and then establishing the pursuit of said goals. So it’s much more of an intimate and insular process in my case.

UMS: Are there artists who take a similar approach from whom you take inspiration?

CS: There are artists really across the board from different genres and different eras that I take inspiration from but not necessarily in a process sort of way. I don’t really know that I’ve ever specifically inquired into someone else’s process and then been inspired by that, so much as I am inspired by the finished product, and what that does and their intention, the intention that’s successful, housed in the music that they created, and then transmitted to the listener. So that’s I think more so where I would consciously cite inspiration or influence.

UMS: You have roots in Ann Arbor. Is coming to Ann Arbor special for you?

CS: Of course. It’s where I grew up. So, all the places in Ann Arbor have a little more historical significance for me, in terms of what I’ve done in them. When we grew up, I was playing in the bars throughout campus all through my teens, and then an enormous amount when I was in college. All of those places have a greater lineage for story for me, some much more so than others.

UMS: Last time you performed in Ann Arbor, you played the Blind Pig, and this time you’ll be performing in more of a theater space. Does the venue change your approach to the performance?

CS: Very much so. One of the things that I’ve been really lucky with in my career is having this extremely disparate selection of venues that I play at. Throughout a tour I can be playing at jazz venues and little clubs, rock venues, some very large, and churches, proper theaters.

So there’s been an enormous amount of different venues, and they’re all very specific in how they accept sounds and how they reflect sound and how they treat an audience, how an audience feels in that space, whether they feel attentive and intimate or exposed, or whether it’s a loud space where there is much more extraneous noise.

A rock club doesn’t necessarily feel better or worse, but there are just differences. There I can rely more on the sheer mass of sound because that’s kind of the domain of the rock club, is moving a lot of air, moving a lot of sound, and filling up in that way. And in a theater, where the convention is more along the lines of sitting very quietly, shunning all extraneous noise, exposing all the minutia, I’m really able to exploit that.

UMS: Kronos Quartet is also a part of our renegade week of performances. Do you like that group’s work? What makes that work stand out?

CS: They were hugely formative for me and my friends when we were coming up. We met in the university, and we were training largely classically, and sometimes academia tends to compartmentalize to such a degree when it comes to genre and idiom, so you know, here is the improvising group, and here is the classical ensemble, and here is the jazz ensemble, and everything is really toeing the line.

But what we were really interested in was just music that came very intuitively to us because we were listening to improvised music, because we were listening to soul and R&B, because we were listening to metal, the music that came out of us tended to be an amalgam of all of that, a much more organic mixture.

And here was a group, Kronos Quartet, who was doing just that. They were forging a path that was not pre-established or genre-specific, and doing it in such an incredible way, they’re such brilliant artists and technicians. It was a great example for young players, and continues to be, musically, for me and my friends now.

Interested in learning more? Check out our Colin Stetson listening guide “Wild Forces at Play.”

Interview: Garrett Schumann interviews Composer George Crumb

Photo: Kronos Quartet. Photo by Jay Blakesberg.

Known for its renegade spirit, the Kronos Quartet will perform two different programs on January 17 and 18, 2014 in Ann Arbor. The first program will include George Crumb’s epic work Black Angels, a response to the agony of the Vietnam War,

Our regular Lobby contributor Garrett Schumann sat down for an interview with George Crumb. Read on to learn more about the composer’s influences, his life in Ann Arbor as a doctoral student, and the debut performance of Black Angels in Rackham Auditorium.

Garrett Schumann: You describe Black Angels (1970) as a reaction to the Vietnam War, and I’m curious how the meaning of the piece to you has changed or persisted in the 43 years since you wrote it?

George Crumb: Well, Black Angels was played to pieces, as you probably deduced. It’s more than 40 years old now, but I remember that it was a very difficult piece to write. As far as it relates to the Vietnam War, I had to discover that myself because I didn’t set up to write a political piece. I think that the upset in the world found its way into the music, which happens so frequently.

There are many works throughout music history that are reactions to political events, but in this case it kind of crept up on me. At a certain point, I realized that it was becoming a reflection of a lot of the anxiety and uncertainty of those days. It was a pretty bleak period.

And that coincided with all of the protest movements around the country, which kind of led to a whole new kind of America.

GS: In 2008, the New York Times reviewed a Kronos Quartet performance of Black Angels, and commented that the piece inspired David Harrington, the Kronos Quartet violinist, to form the group. I know Kronos Quartet started playing Black Angels very soon after they formed, and they have performed the piece a lot, and will perform it as part of their upcoming performance in Ann Arbor in January. I’m curious what you think their experience with the piece brings to their performance of it.

GC: It’s interesting, the Kronos Quartet quickly became well-known, but I’ve never worked with them. Most quartets would ask me to sit in and listen to their performance. I didn’t sit in on any rehearsals before they began playing it, so what they brought to it was entirely their own. It was interesting to me to see how a group of musicians would face all of the problems in the piece without my intervention.

And by the same token, I was never been in on the recording sessions. There have been quite a number of Black Angels recordings, and I sat in on many of them, but not in this case.

So those are interesting things for me, and another thing is the way they kind of superimpose a theater gesture on top of the score itself. Their interpretation is a little freer than some of the quartets who have done the work. I think the music allows room for varied interpretation, and they bring their own thing to the music.

GS: There’s a lot of imagery built into the way you write music, so do you see a theatrical interpretation as a sort of extension from that visual aspect that’s embedded in your music?

GC: Yes, I think that sort of thing seems a natural way to approach my music. There are no instructions for that in my score of Black Angels, any kind of special theater effect, but I would like to see more of that in music generally. I’ve always felt that traditional music had that curious, almost poetic, thing built into it. And the musicians have to move. In a way, they’re dancing with their instruments. This sort of thing is part of music, so I can understand how performers sometimes might even want to accentuate that side of it.

GS: What was the impulse, early on in your career, or maybe even before you knew you wanted to compose, to manipulate instruments in unusual ways, to create different sounds?

GC: Many composers had a big influence on my music. One was Béla Bartók, I felt the real power of his influence when I, myself, was a graduate student in Ann Arbor. There’s also a little of Messiaen in my music, comes out in the cello solo part of Black Angels. There’s a little Messiaen-ic sound. It’s an unconscious borrowing, but I recognize it was a borrowing later on. It’s there.

GS: What are your recollections of being here [Ann Arbor] as a doctoral student and has your experience here influenced you at all beyond your education?

I enjoyed so much studying with Ross Lee Finney, he was my only teacher during those years. He really insisted on the clarity of notation, and I’ve never had anyone else I’ve worked with who placed as much stress on that aspect. Another good thing about it is that there were so many students in the graduate program; you learn from your classmates just as much as you do from your teachers.

GS: When you wrote Black Angels, you used folk songs, which are heavily loaded as a symbol of American identity. Do you think it’s important for American composers to address those aspects of national identity directly?

GC: Well, I think it’s a strong element in music generally, and an important thing for a composer to have. If you consider a composer like Stravinsky, all the melodic elements are derived from Hungarian folk songs. And it’s hard to think of Brahms and Beethoven without all of the built-in references to German folk songs.

Black Angels quotes other composers, and it has this quasi-antique music. It’s really a pastiche. These materials can be used by composers to add a kind of depth or perspective. It’s like two different worlds coming together.

GS: Is there something you would like people who haven’t heard Black Angels before to take with them into the concert hall?

GC: I don’t think I’m able to really verbalize that very well. And I guess what the composer should say is: Listen with open ears and try to fit it together. There are the qualities of anguish and love, even, pain; it’s a mixture of all the things our world is made of.

GS: Is there anything else you would like to add?

GC: I wanted to be sure to mention the Stanley Quartet, who did the first performance of Black Angels in Ann Arbor. I had just gotten a commission from them to do a quartet, and I said to myself, I want to write a quartet that’s unlike any other quartet. I want to do something a little original. And I didn’t realize it then how far I would push.

I think they must’ve been totally surprised when they got the score. They finished the piece, read it through. I went out to Ann Arbor a couple days early to make some explanation. They had a million questions. There were different ways of playing their instruments, there were unconventional ways they had to produce the sound.

They hadn’t played much contemporary music, so they were willing to do anything I wanted. And I ended up conducting, can you imagine? I felt like a fool conducting a string quartet, but it helped them keep it all together, and they did a marvelous performance.

There was quite an enthusiastic reception. I think they [the audience] were probably at least in their sixties, verging on seventies, so I’m sure that none of them are alive now. But they sure came through for me and they were really willing to exert themselves and put this thing together, which amazed me.

Interested in learning more? Read our interview with Kronos Quartet’s David Harrington, who describes Black Angels as the piece of music that inspired him to start the group.

Our Interview with Kodo’s Jun Akimoto

Photo: Kodo in performance. Photo by Takashi Okamoto.

Kodo perform in Hill Auditorium on February 15, 2013. With over twenty visits to Ann Arbor over the years, Kodo return with a brand-new performance that includes new visual flair alongside its high-energy percussion, elegant music, dance, and the striking physical prowess needed to sustain a precise yet powerful sound.

We chatted with Jun Akimoto, the group’s company manager, about the power of taiko drums, Kodo’s mission to represent the living folk performing arts of Japan, and what they’re looking forward to in their upcoming visit to Ann Arbor.

UMS: Could you talk about the choreography of Kodo performances? What does it mean to be a part of sharing this rich Japanese tradition?

Jun Akimoto

Jun: Our artistic director Mr. Tamasaburo Bando, is responsible for the artistic direction of Kodo, and he has been working with us for 12 years. Actually, it does not seem to sound appropriate for us to call the movements of Kodo “choreography” since the company’s focus is Japanese drumming, not dancing. Having said that, Mr. Bando, is a renowned Kabuki actor and dancer. His rich and profound philosophy and knowledge and technique of “body” have inspired Kodo immensely at the deeper level. Body movement techniques generally used in many of the Japanese performing arts have something in common beyond the different forms and styles, so the performers of Kodo often feel a kind of cultural synchronicity in Mr. Bando’s comprehension about “body.”

UMS: Can you share your experience about the Kodo Village? How does living there enhance your craft?

Jun: Sharing time and place during the daily life in the Kodo village surely influences what the each member of the company thinks and creates. Particularly, Kodo is known for the collective beauty and unity of the performance. This unity comes from how members of Kodo live at the headquarters of Kodo on Sado Island.

In Japan, I think this sort of mental/physical connection has been cherished and inherited from the traditional way of life in the Japanese feudal societies of the past, which were mostly supported by agrarian communities. Sado Island is one of the rural regions that still retains the traditional ways of life. Kodo owes so much to Sado and the local people, because living there constantly reminds us that folk performing arts are an important part of the life of a community.

UMS: What are the different types of drums that will be used during the performance? What do some of the drums represent?

Jun: Japanese drums, or taiko, have a very simple structure, but they are also seen as the communication tools used between the gods and the people, nature and the people, and people and people. Taiko is a very popular instrument in Japan and is often found in most shrines and temples.

Some types were originally imported through China and Korea. Kodo uses several types and sizes of taiko on stage, but we always feel that the simple but beautiful (and very strong) instrument acts as a door that opens us to the nature. These drums are made of a wood trunk with animal skins tacked to the drum body. It is said that the gods reside inside the taiko and the harder the drums are played, the more pleased the gods become. And, most importantly the drums are the symbol of community and unification.

UMS: Your music is a powerful reflection of both the history and the future of Japanese performing arts. How to you hope Kodo will evolve in the years to come?

Jun: The history of taiko as part of the commercial performing arts is still young and in development when compared to other established Japanese professional performing arts with hundreds of years of history, such as Noh, Kyogen, Bunraku, Kabuki, etc.

Kodo prioritizes the direct connections with the actual living “folk” traditional performing arts found in many regions in Japan (often in countryside and unknown to outsiders). These folk performing arts solidify a community through ceremonies, festivals, and rituals. In the years to come, Kodo hopes to not only continue as a commercial performing arts ensemble, but to be true to direct voices of living folk performing arts.

UMS: What cultural message do you hope will resonate with the audience of Ann Arbor?

Jun: We are very fortunate and honored to have had a long relationship with Ann Arbor. As generations shift both in Ann Arbor and in Kodo, we truly hope that Kodo will continue to refresh, develop, and keep our good relationship between the people in Ann Arbor and Kodo. We are looking forward to performing “Legend” (our new production) in Ann Arbor very soon!

Our interview with Gabriel Kahane

Gabriel Kahane performs January 17 and 18 in Ann Arbor. We asked him a few questions about his collaborations and influences.

Kari Dion: You’re a composer, pianist, and singer. How have these three areas of focus influenced you as an artist? Which do you find the most rewarding right now?

Gabriel Kahane: I actually think of my work in those three areas as being inseparable, inasmuch as a good deal of the work that I do is created for myself, by myself, at the piano, with my voice. It’s almost as if it’s become a single instrument that comprises smaller parts. Obviously there are instances in which I’m asked only to play or just to sing, but by and large, the work that I do involves all of those elements at once.

I do, however, draw distinctions between the work that I do in various musical realms, i.e. theater, concert, and popular idioms. What I’ve found, though, is that work in each of these modes informs the other. For example, if I’m writing a three minute pop tune, the concerns there might be narrative concision and clarity on the one hand, and musico-architectural tautness on the other. Those concerns are present just as much, if on a different scale, in my work in theater (where narrative clarity is often the focus), as well as in concert music (where I spend a huge amount of time thinking about architecture). The same feedback occurs in reverse– if I’m exploring a new kind of polyrhythm or harmonic idea in a concert work, there’s no reason that I won’t try to work it into a pop song as well. So there’s a kind of fluidity between all of these endeavors.

As to the question of which I find most gratifying… it’s hard to say. I think I’m a pretty strong candidate for undiagnosed ADD, and the diversity of my artistic activities allows me to throw myself into a project for a few weeks, months, or sometimes years at a time, and then move onto the next thing. It’s all deeply rewarding, if a bit overwhelming.

KD: How do you go about tying together your classical roots with contemporary influences in your music?

GK: The practice of bringing together formal compositional procedures that occur in “classical” music on the one hand, and vernacular or popular elements on the other, is as old as Bach. Throughout Western musical history, we’ve seen composers borrow and transform popular or folk material in the context of concert works– Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, Mozart, Mahler, Ives, you name it — they were all having a conversation with popular forms. The reason we are so fixated on this age old practice now is that we’ve only just come out of a brief dark age, say 1946 to 1981, during which concert music was hijacked by an extremely academic strain of composer, leading to a musical output that had entirely lost its connection to the vernacular. But as large classical institutions began to acknowledge (with say, the landmark commission of John Adams to write Harmonium for the San Francisco Symphony for the 1980-1981 season, hence the end date of my proposed “dark age”) the artistic legitimacy of new movements like American minimalism and its various offspring, the academy gradually lost its grip on determining what was “acceptable” in the concert hall. I realize this might seem like a bit of a dodge, but it’s only because I think the question is slightly to the side — I’m using the same kinds of techniques to reconcile popular and concert idioms that any number of composers has been using for centuries. What is most interesting to me is to look at the meta-narrative, the tale of our musical tradition over the last three-plus centuries, and to realize that what happened in the middle of the 20th century was an aberration.

KD: Have you always been interested in collaborating with other artists and ensembles?

GK: Yes, I think collaboration has always been important to me. Growing up, I spent a lot of time acting in plays and operas, and the theater, as you know, is a very community-based art form. One of the things that I like about toggling back and forth between my work as a composer of formal works and that in the theater is that it allows me pockets of deep solitude (in the former) and intense collaborative and communal experience (in the latter).

I have to acknowledge here, that I am an insane control freak, but I’ve learned that collaboration is totally worthless if you don’t trust the people you’re working with to do what they do well. So I feel more comfortable delegating in certain situations now than I might have a few years ago. For example, while working on February House, the musical I wrote for the Public, I grew to trust my musical director Andy Boroson so much that I would leave the rehearsal room to work on a new song, knowing that he would formulate, say, scene change music that matched what I would have had in mind had I been present. Or in the pop realm, my dear friend and colleague Rob Moose (one of the founders of yMusic and heard on these concerts) is not only a phenomenal guitarist and violinist, but a first-rate arranger as well, so it’s been my pleasure to hand off the occasional arrangement of a song of mine for him to do, even though I wish I had the time to do them all myself. Rob and I have also done some in-studio collaborating where I’ve brought fully notated string arrangements in and then we’ve adapted them based on his input. And all of that is predicated on trust, especially, as I said before, when you’re a control freak. (STAY OUT OF MY KITCHEN!)

KD: What is your most memorable musical collaboration?

GK: I think the collaborations that I remember most fondly are with two musicians, Chris Thile and Brad Mehldau, and both are still ongoing, if sporadic. Chris and Brad are two of my favorite musicians on the planet, and both incredibly gentle and sweet human beings. There was one gig in Denver a few years back where Chris was in town playing his Mandolin Concerto and I’d flown out to hear it as well as to do a club date in town, and on his night off, he came to sit in. We were playing/singing a tune of mine which we hadn’t exactly rehearsed, and in the middle of it, we spontaneously broke off into a kind of improvised counterpoint that eventually wound its way back to the end of the song. It was one of those moments that just felt entirely satisfying. Similarly, I’ve had Brad sit in on gigs of mine in New York, often to accompany me singing standards, which is a sort of closet fetish of mine. And you couldn’t you really ask for a better pianist to support you in that mode!

But there are so many collaborations that have been richly rewarding. A huge amount of what I know about writing for orchestral instruments came from my first encounters with yMusic, who were incredibly gracious in helping a self-taught/newbie like myself what was and was not idiomatic (i.e. physically comfortable to play) on their respective instruments. I just finished writing a new piece for them, almost 5 years after I first wrote for them, and I’m astonished both at how much I’ve learned, and at how much I’ve still yet to grasp.

KD: What drew you into collaborating with yMusic? How do they complement or add to your personal sound?

GK: My collaboration with yMusic grew out of my friendships with Rob Moose and CJ Camerieri. They were just formulating the idea of this group, a new music ensemble that was equally comfortable in pop and classical settings, when I received an invitation to write a chamber work for the Verbier Festival in Switzerland. I decided that they were the perfect ensemble to workshop the piece that I was going to write (which ultimately became For the Union Dead, on poems by Robert Lowell) and set about putting pen to paper. yMusic shares my reverence for vernacular and concert forms, as well as the desire to let them meet in the middle. Their sense of rhythm is different than a lot of more traditional classical ensembles; theirs is predicated on a deep understanding of “groove” or “the pocket”. Groove can mean a lot of things, but it’s certainly an undercurrent of a good deal of the music that I’ve written to this point, and I always trust yMusic to translate what’s imperfectly notated on the page into the feeling that I want in performance.

KD: We can’t wait to have you in Ann Arbor. Is there anything else you’d like to add?

GK: I’m thrilled to have this opportunity to present an evening of music with my friends and colleagues. It’s not often that I get to bring the full ten piece band out of the hangar, and I suspect we’re going to have a lot of fun over our two night stand in Ann Arbor.