Reimagining Euripides: A 21st Century “Trojan Women”

Editor’s Note: SITI Company perform Trojan Women (after Euripedes) at the Power Center on April 27 and 28. The following post is excerpted from The Getty Iris, the online magazine of the Getty where Trojan Woman premiered last summer.

Euripides’ Trojan Women is over 2,400 years old. This work is one of the most enduring and moving classical dramas—and one of the greatest antiwar plays ever written. SITI’s adaptation premiered at the Getty Villa in Los Angeles last year, bringing a fresh approach to this ancient work.

Getty’s Desiree Zenowich talked with Norman Frisch, who oversees the mounting of the Villa’s annual Outdoor Classical Theater production, about the genesis of the SITI adaptation and what audience members can expect to see.

This play is not titled Trojan Woman, but rather Trojan Women (after Euripides). Why?

This isn’t a literal staging of the ancient Greek play. Anne Bogart, the artistic director of SITI Company, approached us with the idea of reimagining Euripides’ action for a contemporary audience. She meant, in essence, using Euripides’ text as a starting point, but imbuing his characters with the sensibilities and souls of 21st-century individuals. The result – which has been very skillfully adapted by playwright and dramaturg Jocelyn Clarke – uses Euripides’ play as a basic framework and then both subtracts and adds to it.

What changes did playwright Jocelyn Clarke make to Euripides’ text?

Most noticeably, Clarke has eliminated the large chorus of Trojan women that gives Euripides’ play its name. In Euripides’ text, Queen Hecuba, who has just seen her husband and sons slaughtered and her city of Troy sacked by the invading Greek army, sits at the center of a large number of other widows and mothers who await their transport into slavery and exile.

Clarke’s text for SITI Company focuses much more tightly on the plight of the Trojan royal family. As morning breaks over the smoldering ruins of Troy, only the royal women—Queen Hecuba, her priestess daughter Kassandra, and her two daughters-in-law—remain alive in the palace, detained by the Greek generals who will decide their fates. The three sisters and their mother are onstage together through much of the evening, and each exhibits a very different response to the apocalypse unfolding around them.

In this sense, the SITI Company version of the legend is a far more domestic, family drama. It’s more Chekhovian, so to speak.

A Chekhov-inspired Trojan Women?

Clarke’s text echoes of the more recent history of drama, and of warfare. In addition to Chekhov, in rehearsal I also get frequent flashes of Brecht, of Samuel Beckett, of Ionesco, and of Harold Pinter.

In Clarke’s play, we see not only the culmination of the Trojan War, but also get flashes of the Russian Revolution, the Holocaust, the Balkan wars, and so on. While this Trojan Women doesn’t transport the action to a modern setting, the Greek and Trojan heroes nevertheless behave like contemporary people.

You’ve mentioned an element that’s been eliminated: the large chorus of women. Are there characters or elements that have been added?

There are; two, in particular. First, a major figure in Euripides’ play is constantly spoken of, but never appears: the crafty Odysseus, the Greek general and king who devises the famous wooden horse that finally delivers the city of Troy into the hands of its Greek enemies. A strategist and a realist with a very modern sensibility, Odysseus enters the action of the SITI production toward the end of the evening, and his face-to-face encounter with Hecuba and her daughters catalyzes the final scenes of the play.

Second, although we know that the culture and religious practices of the Trojans were vastly different than that of the Bronze Age Greeks, Euripides’ play does very little to illuminate those distinctions. This was clearly not one of his central concerns.

By contrast, the SITI production introduces the figure of a Trojan priest who accompanies the royal women in their final hours: a eunuch and acolyte of the fertility goddess Kybele. Through this newly-invented character, we get a far more precise impression of why the goddess-worshiping Trojans and their “feminized” worldview are held in such contempt by the conquering Greeks, whose values are entirely patriarchal and religion solely Olympian. We understand more clearly why the Greek generals feel compelled to reduce Troy to cinders—not only in order to plunder its vast wealth, but also because they fear and despise its “degenerate” and “effeminate” culture.

Tell us a bit about SITI Company and its director, Anne Bogart.

Since its founding 20 years ago, SITI Company has been one of the most experimental theater troupes in America. Its training practice and performance aesthetic were informed by two elements that seemed very foreign and unfamiliar to American actors and audiences in the early 90s.

One was the highly rigorous training regimen and performance style developed by the influential theater director Tadashi Suzuki, who draws upon extreme performance and martial arts traditions rooted deeply in the Japanese culture.

The other was a rehearsal technique termed “Viewpoints,” originally developed in the context of New York’s postmodern Judson Dance movement. SITI Company understood that this choreographic strategy could be expanded and adapted to serve theater artists as well. Indeed, during the past two decades, Viewpoints training has been incorporated into the curricula of hundreds of theater departments across the U.S. and in many actor training programs around the world.

Is Trojan Women a new kind of production for SITI? What kinds of plays does the company typically present?

The SITI troupe has assayed many classic theater texts: a medieval Morality play; works by Shakespeare, Marivaux, and Kaufman and Hart; even radio plays by Orson Welles—a vast spectrum of historic dramatic material. And with each new production, the reputation of the company, and of director Anne Bogart, has increased and widened.

Director Anne Bogart will give a pre-show talk on April 28.

Not Quite-Live-Blogging Robert Wilson and Philip Glass Conversation at the Michigan Theatre

Editor’s Note: Last night’s Penny W. Stamps Speaker Series featured a conversation with Einstein on the Beach co-creators Philip Glass and Robert Wilson. Anne Bogart, acclaimed theater director, moderated the conversation. Leslie Stainton blogs about the event below.

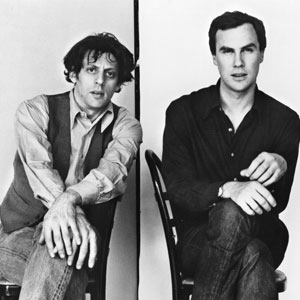

Photo: Philip Glass and Robert Wilson.

3:45 pm*

I have to ask someone to move over a seat so that there’s room for my two friends and me. The place is jammed, top to bottom. Balcony, orchestra. There’s a sound guy behind me, and a videographer up front, and dozens of people are milling about in the aisles. You’d think the Golden Globes were taking place.

*Times are approximate

4:15 pm

After a round of introductions, director Anne Bogart, who’ll moderate the conversation, takes the podium. She tells us A2 is the place to be this coming week, because we’ll get a window into the “extraordinary trajectory of this production.” She reminds us that since its inception in 1976 and its last iteration in 1992, “our lives have become faster and faster.” Einstein, she notes, “changes the time signature”—a suggestion I find beguiling.

4:20 pm

We see documentary video footage of Glass and Wilson, with snippets of the original 1976 production. Either Glass or Wilson—I can’t remember which—describes Einstein as “the god of our time.” I wonder if that holds for the 21st century?

4:30 pm

Wilson and Glass take the stage to rapturous applause. Bogart mentions the ovation. “We haven’t done anything yet,” Glass mumbles. Laughter. Surely I’m not the only one thinking, “Oh, but you have.”

4:35 pm

Wilson describes the early stages of Einstein’s development. He and Glass shared a “common sense of time and space,” he remembers. They agreed on a common megastructure and a total time length. Each man followed the same structure but filled it in different ways. This is a theme Wilson will repeat throughout today’s conversation: Form—whether of something as big as an opera or as minute as an actor’s gesture—is less important than how it is filled. Appearances to the contrary, the form of Einstein is “very classical, very formal,” Wilson says, and something we should all recognize—theme and variation.

4:40 pm

Glass observes that every time they’ve produced Einstein—in 1976, 1984, and 1992—they’ve drawn huge numbers of young audience members. Judging from the crowd in the Michigan, it’s still true.

4:50 pm

There’s talk of how radical it was in 1976 to produce an abstract work like this in a conventional setting like the Metropolitan Opera House—at a time when lofts and street theater were the rage. (Wilson remembers thinking, “What’s wrong with illusion?”) He and Glass had to rent the Met for a day in order to put on Einstein that day. “We didn’t actually have the money,” Glass interjects. Because of the opera’s five-hour duration, without intermission, the Met bars made a killing. I’m reminded that the Power Center can’t sell booze, which seems a pity.

5:00 pm

Wilson urges audiences to come and go during Einstein the way they would in a park. “It’s always going on, something is always happening.” This way, there’s “not so much difference between art and living. If you want to sit for five hours, that’s OK. If you leave in the second act and come back in the fourth, you’re not lost. It’s not like Shakespeare.” Much laughter.

Glass adds, “The audience completes the work. The piece by itself doesn’t work.”

5:10 pm

On process, both Wilson and Glass caution against knowing too much when you embark on a project. Glass: “If I know what I’m doing, then I don’t have anything to do.” Wilson: “As I got older, I learned that if I pre-decide, I often waste time, instead of going in with no idea. Let the beast talk to you instead of you talking to it.” Both say the starting point of a piece doesn’t matter. The process itself becomes the content.

5:15 pm

Glass gets a laugh when he recalls how John Cage once chided him: “Philip, too many notes.”

5:20 pm

Performer and choreographer Lucinda Childs joins the conversation. Bogart speaks of how riveting Childs’s performance in Einstein was when Bogart first saw it in 1976 and again in, I think, 1992. Bogart’s referring to the moment when Childs spends 20 mintues crossing the stage back and forth on a diagonal. For years Bogart wondered why she couldn’t take her eyes off Childs, what Childs had to teach her about the arts of acting and directing. The answer—proposed here by Wilson—seems to be that as an actress, Childs filled every single moment. He talks of the “sheer stamina” the production demands of actors, which is matched, he adds, by the stamina of watching it.

5:25 pm

Wilson unlocks something for me when he speaks of the difficulty some critics have with Einstein because it’s abstract. We can accept works by Jackson Pollock as abstract, Wilson explains, but not something we call “opera” or “theater.” Nor do conservatories or theater schools tend to include the term “abstraction” in their curricular vocabularies. Wilson says abstraction is liberating for him. This seems critical to understanding what we’re about to see onstage this week.

5:30 pm

Questions from the audience. Long lines form in both aisles. The first questioner wants to know why the opera has such short runs whenever it’s produced. Money, Glass answers. Wilson claims the same production will cost 3-4 times more to mount in New York City than in Paris. A stagehand at Carnegie Hall, he adds, makes more money than Obama.

Someone asks for advice for young artists. “Keep working,” Wilson urges. He’s not being facetious.

A stage-design student wants to know how to meld set, costume, and lighting design. Wilson notes that in conventional opera staging, sets often distract from sound, and vice versa. The question designers and directors should ask, he believes, is “How can what I am seeing make me hear better? Can I create something onstage that makes me hear the music better than I do when my eyes are closed?”

5:40 pm

In response to a long-winded and confusing question about novels and language, Wilson is more than generous. He speaks of his work with autistic children, of the difficulties that ensue when actors inject their own emotions and feelings into texts rather than letting the texts speak and audiences decipher their meaning for themselves. He says it’s “OK to get lost” when you’re reading a complicated novel or listening to a Shakespeare sonnet (or, we can infer, watching something like Einstein). “TV has changed our way of thinking. Do you understand? Do you get it?” TV is forever asking that, forever explaining. Wilson: “It’s OK to get lost.”

5:42 pm

The visual space in Einstein is organized in three very traditional ways, we learn. Portraits, still lifes, and landscapes. Bogart mentions the influence, as well, of vaudeville, and Wilson agrees, noting that Chaplin and Keaton are both inspirations.

5:45 pm

The session ends with an exchange that must warm the hearts of many in the crowd. An audience member asks why Wilson and Glass chose to reconstruct the show here in A2. Glass cites the financial practicalities of mounting a huge production like this in a noncommercial theater and mentions the educational benefits for both audience and cast, crew, and Glass and Wilson themselves.

But Wilson delivers the money quote. Ann Arbor, he says quietly, “is one of the cultural strongholds of this country.”

With that, Bogart ends the discussion and sends us out into the cold. The sun has set, the sky is a pale lavender, and the street lights are glittering. The place feels even brighter than it did two hours ago, in full daylight.