Renegade Reflections – Guest Blog by Leslie Stainton

Editor’s Note: Lobby contributor Leslie Stainton will guest blog the San Francisco Symphony American Mavericks festival throughout this weekend. Read her notes on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday.

What’s next for Jeremy Denk? Definitely not Disneyland. After Sunday’s rollicking performance of Lukas Foss’s “Echoi”—a pseudo-string quartet that lent new meaning to the word “string”—the pianist was heading to Carnegie Hall, where the SF Symphony will reconfigure its Mavericks series for New York audiences this week. Denk said he and his fellow performers are bracing for a different kind of reception from the one they got here. I asked him after Sunday’s performance how he’d liked his week in A2:

Sunday’s concert drove home for me some of what the Mavericks series—and the Renegade series overall—have achieved:

- An expanded idea of what constitutes a musical instrument (Foss’s “Echoi” culminated in a dramatic thrashing of a dusty garbage-can lid) and the sounds that musical instruments—including the human voice—are capable of making. Piccolo as siren, bass fiddle as drumhead, soprano as piccolo. Our isle is indeed full of strange noises.

- A humbling appreciation of how conventional our musical tastes tend to be. Bach on the radio this weekend just didn’t do it for me. I’m sure I’ll swing back, but after the likes of David del Tredici, the Baroque seems a tad tame just now.

- Magnificent resonances—not just within the Mavericks series but within Renegade as a whole. Echoes of “Einstein on the Beach” throughout, most recently in yesterday’s vocal works by Meredith Monk and Morton Subotnick. Hints of the Hagen Quartet’s furious playing in yesterday’s Foss quartet, traces of the Tallis Scholars in Monk’s unorthodox blending of voices, and so on …

- The urgency of live performance—especially now, when we filter so much of our human experience through screens.

- The urgency of a vibrant cultural life—and the need to support it. (Thank you again, Maxine and Stuart Frankel.) Yesterday’s paper brought news of dwindling arts support in Europe. Artists and arts organizations are being asked to justify their existence by demonstrating economic impact. It’s a killer for small, weird stuff like the kind of music we’ve just spent four days absorbing, or something as mind-opening as Robert Lepage’s “Andersen Project.” And yet how vital the enterprise is to being human. I was reminded of it at last week’s American Orchestra Summit here in A2, when two bright and gifted teenagers talked about what music—hearing it, playing it, studying it—meant to their existence. This stuff saves lives, don’t kid yourself.

- The many ways that unconventional work stretches performers and audiences alike. A friend remarked to me yesterday that he’d never much liked contemporary music before, but the Mavericks series had changed him. I feel the same way. This has been a mind-expanding experience—a giant “Maverick martini,” without the hangover.

I asked a few people who’ve been closely involved with the Renegade series since its inception to reflect on the past two months—high points, low points, and everything in between:

“Stretch. That’s the word that’s come to my mind most often over the past 10 weeks, and especially in the past four days with the SFS. I love this feeling that, even when I think I’ve seen it all, something like the Renegade series stretches me in new and exciting ways as an audience member. I’ve felt myself grow, becoming more willing to tackle the ambiguous or unfamiliar, and to give myself over to these experiences in the moment. The big gift of Renegade for me is that it seems to have opened up a much more public conversation about what UMS is putting on the stage, and audiences are describing their experiences in more nuanced and complex ways (we’ve made good progress away from the like/dislike dichotomy!). With Renegade, we set upon a journey of intentional watching/listening/experiencing. It’s been interesting to see how some of us really embrace that idea, and it begins to change in new and exciting ways how we experience performance. And now that the journey has come to an end, I’m aware of how exhausting it can be to be stretched, but I’m looking forward to using this greater capacity that I’ve developed within myself and applying it to next season.”—Jim Leija, Education Director, UMS

“I was constantly on my toes. I was surprised and never knew what to expect. Just as I would sit back and say, ‘Well, yes, yes. this is going to be something I’m familiar with,’ WHAAM, something would happen to engage me/entrance me/surprise me. I am exhausted by LISTENING to all that fabulous music.”—Prue Rosenthal, Former Chair, UMS Board of Directors

“I will admit that I approached the series with some trepidation, not being sure if audiences would be receptive to the works programmed on the series. It was such a thrill on Thursday night to see the instantaneous positive response – a response that mostly continued throughout the four concerts. Not everybody liked everything, nor would I expect them to, and in all honesty, I wish more of the dissenters had posted on the Lobby also. But there was something really powerful about hearing so much modern music in a concentrated timeframe and realizing that it isn’t as scary as it looks on paper. I wish we could clone MTT, who is able to bring meaning to the pieces with just a few words about each composer. One commenter on the Lobby website was dismayed by this music being ‘ghettoized’ (my word, not the commenter’s) in one program, and thought it would be better to have it interspersed with other, more traditional works. But I’m not convinced of that. Henry Cowell in the context of Tchaikovsky or Brahms will have a decidedly different impact than when heard in the context of Varese, Ruggles, or Harrison. These concerts were a great way to introduce the idea that modern music IS accessible and enjoyable, not that it’s medicine that you need to take in order to get the Beethoven. On the whole, I was so proud of our community for embracing this festival wholeheartedly. It’s fine not to like everything – heck, I run fleeing whenever Brahms is on the program! – but the willingness to embrace the unknown was just another example of why I live in Ann Arbor.”—Sara Billmann, Director of Marketing & Communications, UMS

“What made me happiest about Mavericks and Renegades was not always knowing in advance what was going to ‘work.’ Concert programming so often presents us with an unbroken string of success stories, and that was definitely not the case with the American Mavericks’ works, several of which were ‘hot off the press.’ I was thrilled by Varèse, Cowell, Bates (of whom I’d never heard), and Foss . . . and bored by Monk and Subotnick (I don’t handle rhythmic monotony well). What was exciting in most cases, though, was not knowing what to expect. This has been an ear-freshening semester, and UMS has my sincere thanks for that.”—Steven M. Whiting, Professor, UM School of Music, Theatre and Dance; Guest Lecturer, UMS Night School

“I’ll never forget the bookends of the series — Einstein and the San Francisco American Mavericks concerts. Both were transformative to my perspective on culture in American life—watching Einstein be remounted and come into being on campus was phenomenal and gave me a rich appreciation of the work; the symphonic realization of Ives’s Concord Piano Sonata clarified my vision of the work and is still ringing in my ears. Over the course of the Renegades Series, I’ve come to see the figure of the Maverick in American culture as less of an outlaw and more of a driver of innovation, really a thought leader. That Mavericks have become a tradition in America and across the globe gives me hope that we can solve the problems that we face as a nation and world citizens. I’m certain that the Renegade Series has inspired the whole campus, faculty and students alike. Another takeaway has been the incredible value of attending shows that I don’t usually attend — for me dance and theater. UMS provides us with a rich variety of cultural experiences, and I think we as audience members need to challenge ourselves more often to attend things outside of our experience. Certainly the students in my Mavericks and Renegades class have discovered the value of expanding their cultural diet, we’ve all grown as a result.”—Mark Clague, Associate Professor of Music; Instructor, UMS Night School

Unpacking the sets for John Cage’s Song Books

Unpacking the sets for John Cage’s Song Books on Friday, March 23 at Hill Auditorium. Join the discussion and read audience reactions here.

From the UMS Video Booth

Our video booth had a long run over the weekend at the San Francisco Symphony American Mavericks festival.

The Lives of Men – Guest Blog by Leslie Stainton

Photos from the UMS Archive. 1. L-R: Gordon Mumma with visiting composer Morton Feldman, ONCE Festival (1964), Ann Arbor. (Photo: Donald Scavarda) 2. Morton Feldman in Ann Arbor, ONCE Festival (1964). (Photo: Makepeace Tsao, courtesy of the Tsao Family)

Editor’s Note: Lobby contributor Leslie Stainton will guest blog the San Francisco Symphony American Mavericks festival throughout this weekend. Read her notes on Friday and Saturday.

Biography kept popping up. From Saturday’s pre-concert presentation on Charles Ives and his Concord Sonata, to the intros to each of the evening’s pieces, to the final, riveting and mercurial Concord Symphony, character and personality held center-stage throughout last night’s program. I’ve devoted huge parts of my life to writing and reading biography, so I generally don’t need convincing, but I found myself wondering at times last night whether it makes a difference to know, for example, that Carl Ruggles hated Brahms and destroyed much of his own work, or that Morton Feldman was a friend of Mark Rothko. In the end, I think it does.

Before each of the three pieces on Saturday’s program, Michael Tilson Thomas spoke briefly, and fondly, about its composer. Of the difficult and “craggy” Carl Ruggles, whose “Sun-treader” (1931) opened the evening, MTT said, “He spent most of his life pent-up in a small, one-room schoolhouse in Vermont with a piano a pot-bellied stove, and his adoring wife.” On weekends, Ruggles was visited by the likes of Thomas Hart Benton (who used the composer as a model for Ahab in his illustrated “Moby Dick”). Ruggles produced a slender oeuvre—just a dozen or so works—and they’re filled with defiance, rage, deep sorrow, and an aching passion, MTT said. “You instantly know it’s a statement by Carl Ruggles. So get ready.”

And he was right. With its huge and sober sounds, beautiful and raging all at once, “Sun-treader” seemed to me a palpable cry. I kept thinking of Icarus, striding toward the sun in his doomed chariot. And of Ruggles himself—a man who denounced the mainstream, an outlier unafraid of gods.

If Ruggles was a small man who wrote big, MTT said by way of introduction to the second work on the program, Morton Feldman was a big man who wrote delicate music. And then MTT launched into a brief imitation of Feldman—put on your best Brooklyn accent, and you’ve got it. “Dis work is de classiest ting Ay eva wrote,” Feldman (in MTT’s version) might have said about his “Piano and Orchestra” (1931), which MTT described as a cross between Webern and Duke Ellington. Elegant it was, as subtle and moving as a Rothko canvas (to which both MTT and the program notes likened Feldman’s work—MTT noting that “time” was Feldman’s “canvas”).

At one point during this languid piece, I felt as if I were hearing a deeply sophisticated “Peter and the Wolf,” so magically did the work illuminate each instrument in the orchestra, allowing us to focus on color and tone rather than the usual culprits, melody and rhythm. (Is it stretching things to suggest this functioned at least in part as a “biography” of an orchestra?)

Biography returned full-force in Charles Ives’s “Concord Symphony,” the last work on Saturday’s program, with its four sections devoted to four men who inhabited the legendary town where the American Revolution erupted—Emerson, Hawthorne, Alcott, Thoreau. MTT described the symphony as an epic, and it was. Big, bracing, with sudden and exquisite moments of tenderness nestled among passages of utter fury. I’ve always liked Ives, the Connecticut iconoclast who made his living selling insurance and persisted in writing works that few wanted to hear. But this piece brought him to life in ways I hadn’t heard before—and underscored the majesty and “Americanness” of his often nostalgic vision. A woman I spoke to after the performance summed it up: “This felt almost classical,” she said—especially after Friday night’s foray into the world of John Cage.

I do have one question about biography—where are the women in this series?

During intermission, I cornered the American composer and U-M faculty member Michael Daugherty, who was sitting a few rows in front of me, and asked him what these concerts meant to him:

Word has it that Carnegie Hall is having a tougher time filling its house for these concerts next week than Hill (a larger hall in a far smaller community). It’s a credit to Ann Arbor audiences, as Daugherty reminded me:

Cat Calls, Cheers, and the Glories of Sound – Guest Blog by Leslie Stainton

Photo: From left to right: Jessye Norman, Michael Tilson Thomas and Meredith Monk perform in John Cage’s Song Books during the San Francisco Symphony’s American Mavericks Festival at Davies Symphony Hall in SF on March 10. Photo credit: Kristen Loken.

Editor’s Note: Lobby contributor Leslie Stainton will guest blog the San Francisco Symphony American Mavericks festival throughout this weekend. Her first post is here.

The ride—we’ve definitely moved from journey to ride—continued on Friday night with a rollicking three-hour Mavericks program that included a witty tribute to Beethoven, a tempestuous plunge into the pleasures of sirens and things that go thwack, a surprisingly lyrical piece by the same Henry Cowell who’d shattered any peace on Thursday night, and the evening’s most talked-about event—a gloriously funny, straight-from-the-Sixties, half-hour spectacle by John Cage, featuring Jessye Norman, Meredith Monk, Joan La Barbara, and Michael Tilson Thomas. The latter showed off his prowess at the blender by whipping up a smoothie. (Recipe not included.)

Here’s what Bob Wallin, who sat behind me (and is no musical slouch, being a season ticketholder at UMS, Lyric Opera, and Michigan Opera Theater), had to say about it:

Wallin wasn’t alone. When the lights fell on the last of Cage’s mania, someone in the audience began booing. It’s the first time anyone I spoke to can remember a boo in Hill Auditorium. Was he a plant? UMS’s marketing director Sara Billmann swears not, as does San Francisco Symphony’s Susan Key. So here’s my challenge: will the real booer please come forward?

Out in the lobby during intermission, I encountered Garrett Schumann, a composition student at U-M, who thought it was all great fun. He especially liked it that audience members literally stood up to the booer with cheers, thunderous applause, and a standing ovation. Here’s Schumann’s take:

I later ran into a former music buyer for Borders who felt much the same. “I mean, you come to a John Cage concert, what do you expect? It’s not as if this is 1913.”

Whatever else you thought of the Cage piece—which had to have cost a small fortune, by the way, given all the personnel and technology assembled onstage—it was a hoot to be there. A Happening in 2012 in staid Hill Auditorium? Worth every excruciating minute.

The second half of the program—Henry Cowell’s riveting “Synchrony,” with its gorgeous trumpet solo; John Adams’s aptly named “Absolute Jest,” whose opening strains made hay with Beethoven’s 9th; and Edgard Varèse’s pounding “Amériques,” with no fewer than 12 percussionists and a massive brass section—had me wanting to shout with glee as I left Hill. All through the evening, I kept thinking about sound: what we hear when we’re not really listening, how beautiful something as chilling as a siren can be, how innately musical noise is, how many magnificent and bizarre and thrilling and offputting ways humans have managed to create sound. A bass drum suspended 12 feet in the air, a bassoon played with a violin bow, a heckelphone—who knew?

By the end of the evening, even my seatmate Bob Wallin had forgotten Cage:

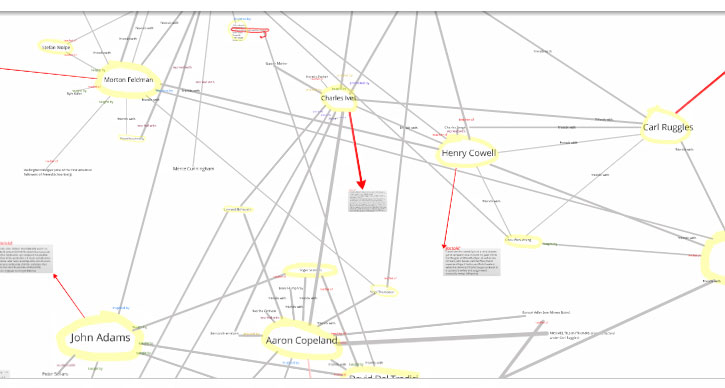

San Francisco Symphony Family Tree

The San Francisco Symphony American Mavericks festival and Michael Tilson Thomas land in Ann Arbor this week. The festival celebrates the creative pioneering spirit and the composers who created a new American musical voice for the 20th century and beyond. We wanted to find out how the composers featured on our Ann Arbor program really hang together. It turns out that they are connected.

Explore the map below to get a sense of the relationships we’ve found between these composers (friends, partners, co-workers, relationships of inspiration…). This map is not a complete picture, but begins to give a sense of the rich musical community which connects these artists and performers.

To explore, click ‘Play’ button. Scroll to zoom in and out and click and hold to move the map. For best experience, click on ‘More’ and ‘Full Screen’ to move to full screen mode. Press ‘ESC’ to exit full screen mode.

Feel free to add yet-undiscovered connections in the comments section below.

We’re thankful to Sam Richards, who compiled the research on which this map is based.

Sam L. Richards is a composer and researcher en route to a doctoral degree at the University of Michigan School of Music, Theatre, and Dance. He frequently collaborates with artists, choreographers, filmmakers, and scientists, and also operates as an interdisciplinary creative consultant for both academic and commercial enterprises.

Livestream Event with San Francisco Symphony

Join us Sunday, March 11 at 4 pm EST for a live web chat with mavericks Jeremy Denk and Morton Subotnick who will offer insights into the music featured in the American Mavericks festival. Submit your questions and chat with others online.

Stream: http://www.sfcv.org/mavericks

Did you miss it? Is it still a few days away? Check out our Maverick Mondays video series in the meantime.

Maverick Mondays Series

This winter, University Musical Society (UMS) is presenting a 10-week, 10-event ‘renegade’ series focusing on thought-leaders and game-changers in the performing arts. San Francisco Symphony’s American Mavericks festival will close the series.

The second American Mavericks Festival, presented by SFS as part of its centennial season, will tour in its entirety to only two US venues: Hill Auditorium and Carnegie Hall.

We’ll be featuring multimedia content for the performances each Monday as part of our Maverick Mondays series.

A behind-the-scenes look at John Adams’ Infinite Jest:

Find out what Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman sound like through Charles Ives’ Concord Symphony:

Conductor Michael Tilson Thomas and pianist Jeremy Denk discuss Henry Cowell’s piano concerto:

Composer Mason Bates talk about his new work, Mass Transmission:

San Francisco Symphony members and Michael Tilson Thomas remember the first American Mavericks Festival:

Conductor Michael Tilson Thomas talks about the meaning of “maverick”:

Learn about the American Mavericks All-Access Pass!