Robert Wilson: Video 50

Robert Wilson fans will have much to do in Ann Arbor this winter.

UMS is presenting preview performances of Einstein on the Beach, an opera by Robert Wilson and Philip Glass, January 20-22. Absolute Wilson, a film which chronicles the epic life, times, and creative genius of theater director Robert Wilson, will be screened on January 9. The film screening is free.

Photo: Robert Wilson. “Video 50,” 1978. Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

In conjunction, UMMA’s Video 50 curates Robert Wilson’s “smaller-scale” experiments in video. Guest Curator Ruth Keffer describes the exhibit:

Video 50 consists of a randomly arranged set of 30-second “episodes”; counting occasional repeats and alternate versions, the 50 pieces of the title number nearly 100. Some of these episodes are static to the point of resembling still-lifes; others are self-contained vignettes that begin and end—or seem to end; any narrative resolution is teasingly withheld. With its use of early video techniques and the highly stylized, fashion-world look of its actors, Video 50 seems dated, but the way in which Wilson wields his domestic-gothic vocabulary is classic surrealism: everyday objects and settings made mysterious or comical or alien by their bizarre juxtaposition to one another, and by an equally nonsensical and cheerfully manipulative score of music and sound effects.

Read the full article in UMMA Magazine.

Q&A with Stile Antico

When UMS presented Stile Antico two years ago, it was one of the most talked-about events of the season. Stile Antico today is firmly established as one of the most original and exciting new groups in the choral music world. We asked the group a few questions.

1. Stile Antico work together without a conductor. What effect do you think working without a conductor has on the music you produce?

When we founded Stile Antico, we set out to explore the wonderful repertoire of the Renaissance in a new way. Instead of turning up to rehearsals and being told what to do, we wanted to work as chamber musicians – like a string quartet – deciding amongst ourselves how the music should be shaped and performed.

This approach throws a huge responsibility onto the individual singers. In a sense, we are all conductors: we need an extremely high level of collective listening to make sure that we always sing with good blend and ensemble. We also have to feel and react to the overall sound that we are making, at the same time as singing our individual lines. In our early years we sometimes rehearsed with our eyes closed, or facing away from one another, to hone our aural skills!

It also means that each singer has the opportunity to contribute creatively to our performances: we decide everything, from tempo and mood to dynamics and articulation, by discussion and experimentation. This means that we rehearse far more than other groups of our type – perhaps three or four times as much! – but, most importantly, that our interpretations ‘belong’ to the individual singers in a unique way, and (we hope!) that our performances are warmed from the inside, since the ideas that underlie them come from the group itself, rather than a conductor at the front. We can be spontaneous and fluid in performance, responding to one another as the mood takes us, and we find it an enormously rewarding way to work.

2. How do you put together a program in this kind of conductor-less collaborative environment?

As well as sharing in the musical decision-making, everyone in the group has individual roles – looking after our finances, website, travel and so on. There are five members of the group who take a particular lead on musical programming, working intensively on developing themes for future concerts and recordings. But everyone contributes to the discussion – our private website even has a ‘wish-list’ where we can all make repertoire suggestions. We generally have three or four programmes on the go at any one time, and work about two years ahead.

3. It’s often noted that Stile Antico is a group of /young/ singers. Do you have any advice for other aspiring young singers?

According to one of our basses, be a high tenor – they’re always in demand! But more seriously: have plenty of voice lessons. However natural your voice, it’s easy to fall into bad habits, and it’s great to have someone keeping an eye on you as you develop. If you’re considering becoming an ensemble singer, then get as much experience as possible, practice your sight-singing, and listen as widely as you can – the better you understand a particular style, the better you’ll sing it. But most importantly: always remember why you want to be a singer – it’s because you love the music!

4. In the spirit of the approaching holiday season, what is your favourite piece of holiday music to sing together?

In the spirit of collaboration, we discussed this at some length. The most popular option was Tallis’ Videte Miraculum, the ethereal responsory which opens our Puer natus est programme. But one tenor insisted that we record his preference for (his own arrangement of) Frosty the Snowman.

5.What are you looking forward to in your second visit to Ann Arbor?

A friendly and knowledgeable audience – and a return visit to Vinology!

Stile Antico perform at St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church on Wednesday, Dec. 7th.

[VIDEO] A Q&A with Audra McDonald and U-M Musical Theatre Students

UMS presented Audra McDonald at Hill Auditorium on Nov 4 as part of the 11/12 season. Prior to the performance, Audra met with U-M Musical Theatre students for a Q&A session.

A transcript of the Q&A session is here.

[VIDEO] Messiah Memories: Father Timothy Dombrowski and “The Bat out of Hill”

UMS first presented Handel’s Messiah in December of 1879. In this second webisode of our Messiah Memories series, Father Timothy Dombrowski, choral union member for over forty years, remembers “The Bat out of Hill.”

Comment below with your own Messiah Memories!

Previously: Episode 1: Jerry Blackstone, long-time Messiah conductor, forgets his jacket on the day of the performance.

[VIDEO] Messiah Memories: Jerry Blackstone, Conductor

UMS first presented Handel’s Messiah in December of 1879. We’re kicking off a webisode series of Messiah Memories from everyone involved over the years. In this episode, Jerry Blackstone, long-time Messiah conductor, forgets his jacket on the day of the performance.

Comment below with your own Messiah Memories!

[VIDEO] AnDa Union from Inner Mongolia

UMS is presenting AnDa Union from Inner Mongolia this Wednesday, November 9th. Discover this group’s incredible history, and learn more about Asia Series at UMS in the video below.

[VIDEO] The Rise of the Countertenor – Philippe Jaroussky

UMS presents French countertenor Philippe Jaroussky with Apollo’s Fire baroque orchestra on November 3rd at Hill Auditorium.

In this video, George Shirley, U of M Joseph Edgar Maddy Distinguished University Emeritus Professor of Voice, discusses the rise of the countertenor.

[LISTENING GUIDE] Flamenco is a Living Art: Your Guide

On November 5th UMS will be presenting Diego el Cigala: one of today’s most exciting flamenco singers and musicians.

On November 5th UMS will be presenting Diego el Cigala: one of today’s most exciting flamenco singers and musicians.

I’m Joseph Pratt. For 20 years I’ve performed flamenco and classical guitar at the Amadeus Restaurant in Ann Arbor and I’m delighted to be your guide to this extraordinary music. Though I grew up in Maine and was first introduced to flamenco through television and recordings—my initial exposure was on an episode of Captain Kangaroo–the music left a lasting impression.

Flamenco is a living art form with enigmatic antecedents. This means that while it has roots with Gypsies and other ethnic groups from Andalusia, the area of southern Spain that abuts the Mediterranean, the palette of flamenco has been enriched by hundreds of musicians and dancers from many ethnic origins. This distinctive music has been the soundtrack for the complex and often violent history of the Andalusian underclass. Also, this compelling art form will sound to the listener as though two different times or eras were superimposed: a rich cultural past inspiring a dynamic, fast changing present. Flamenco musicians have learned from the traditions of their cultural past and use those rhythms and voices in their outreach to other musical forms. Where and with whom did this all start?

During the years Spain gorged itself on Aztec gold, an underclass of Arabs, Jews, Roma, North Africans and South Americans poured into the ghettos of Seville bringing with them each their own musical heritage. Not invited to partake of their host country’s riches, the oppressed sang and danced their sorrow in the same spirit as African slaves in the New World. There was a strong current of fatalism in the people who made this music. They generally had no political recourse and were limited in the choices they could make about their own lives. Sorrow, anger, and frustration came out through the music of flamenco: a collective autobiography of hated despots, hopeful lovers, broken men, and distressed women. All the while flamenco incorporates beautiful costumes and cunning virtuosos in it’s juxtaposition of good and evil, just and outlaw which makes flamenco a compelling dynamic experience—one that never fails to raise hairs on the back of my neck.

In many ways then, flamenco was a ‘world music’ before critics coined that term for sounds that bridge form and culture. In recent years Diego el Cigala, an artist originally born in Madrid has added more twists.

Diego el Cigala is particularly good at interpreting what is known as the ‘solea:’ a form of song that expresses the feelings of deep spiritual hardship and is thought to derive from Romani songs carried over generations, from the Indian subcontinent. In a New York Times interview El Cigala says: “Flamenco has to be suffered” and this is very much the tradition of the solea song form. This is not called as ‘cante jundo’ or ‘deep song’ for nothing! While listening, notice his raspy style of singing which is a characteristic flamenco vocal sound known as the ‘voz afilla’. Some would say that voz afilla is the sound of the ripping and tearing of the soul of the singer.

Did you notice how he occasionally claps his hands? Flamenco is a music very rich with rhythm and it has a unique system of accents and beats that can sound unusual to ears conditioned to hearing the music typically played in North America.

Listen to this next video of a song called Flamenco por Lorca . This type of song is called a ‘bulerias’ and is rhythmically similar to the solea but is played at a greater tempo. Take in the floating aural sensation of the flamenco beat. The percussion instrument that that looks like a box is called a ‘ cajon’ which is Peruvian in origin. It was discovered by the great flamenco guitarist Paco de Lucia in the 1970s when he was given a cajon as a gift while on tour in Peru. Paco de Lucia is hailed to be the greatest living flamenco guitarist and has given several UMS sponsored concerts. He liked the sound of the percussion instrument so much that he incorporated it into his own music. The appreciation of the cajon caught on and is now part of the sound of contemporary flamenco. Notice, also, that many hands clap out rhythms called ‘palmas’ and additionally notice the percussive effects played out on the guitar.

Now to Diego el Cigala’s new contribution to the fusion of flamenco where he explores tango. In this video, El Cigala applies voz afilla to the chords and beat of Argentinian tango. While the sound is beautiful to listen to, purists would find this selection not to be authentically Andalusian. Still, its spirit maintains a heat and passion for the flamenco singer to identify in his soul.

Currents of time and history will decide if the tango form will become intertwined with the genre of flamenco. In that spirit, the November 5 performance, which promotes the artist’s new album (Cigala & Tango) may act as a catalyst for an entirely new arm of flamenco – yet another twist in the continuity of a spectacular sound.

Q&A with Gate Theatre Artistic Director Michael Colgan

The Gate Theatre Dublin is synonymous with the works of Samuel Beckett, having toured productions throughout the world from Beijing to New York, Sydney to Toronto and London to Melbourne. Gate Theatre performs Beckett’s Watt and Endgame at the Power Center October 27-29. Michael Colgan is the Artistic Director of Gate Theatre.

Photo: Rosaleen Linehan and Des Keogh in Endgame.

Leslie Stainton: Your current season includes a contemporary memoir, an adaptation of Little Women, and Noel Coward’s Hay Fever, among other works. How does Beckett fit into this picture—and into the overall vision you’re trying to achieve with the Gate?

Leslie Stainton: Your current season includes a contemporary memoir, an adaptation of Little Women, and Noel Coward’s Hay Fever, among other works. How does Beckett fit into this picture—and into the overall vision you’re trying to achieve with the Gate?

Michael Colgan: It’s not really about how Beckett fits into a picture or indeed any other writer for that matter. It is rather about an audience fitting into a work and the best way of accessing a multitude of audiences within a given season. To suggest there is a picture, would suggest there is one specific idea we want to fulfill. In contrast I would suggest that what the Gate aims to achieve and has achieved, is a smorgasbord of writing which is united by a dedication to quality, to theatre and a pledge to investigating a range of human experience. Indeed I mean quality in every capacity but particularly in terms of performance. It is no coincidence that the Gate has been lucky to acquire some of the best performers and creatives in the world and this is in a bid to deliver a work to its greatest standard. Yes, I have a particular love for the work of Samuel Beckett but as he himself has put it ‘Habit is a great deadener’ and so if there has to be an overall vision, it is one of a faithfulness and commitment to producing the highest standard of production in terms of any piece of writing and on this, as Beckett would say, ‘I have my faults but changing my tune is not one of them.’

LS: In this time of recession, war, climate change, and political and religious extremism, what insights and consolations, if any, does Beckett offer?

MC: A lot of the time, there is the ignorant association with the work of Beckett that his ultimate sentiment is bleak. This could not be further from the truth. Yes there is the general air of what Tennessee Williams might call ‘the charm of the defeated’ and a sense of surrender within his oeuvre with lines like ‘the sun shone, having no alternatively, on the nothing new’; but as he himself purported ‘nothing is funnier than unhappiness.’ Beckett finds such humour in the mundane and this is achieved with an acute sense of contradiction within single sentences and the skill of undercutting expectation of change with a line like ‘you cried for night- it falls. Now cry in darkness.’

What he shares with Joyce are subjects who are unable or unwilling to escape the situation of their lives but instead of dwelling on that inability he celebrates fallibility and imperfection acknowledging that ‘you’re on the earth (and) there’s no cure for that ‘. It is by acknowledging failure that he can suggest ‘try again. Fail again. Fail better.’ There is a sense that there is possibility but that there is a responsibility involved in its achievement. As Estragon and Vladimir say in Godot, ‘ We always find something, eh Didi, to give us the impression we exist?.. ‘ Yes yes, we’re magicians.’

LS: Technology is increasingly defining our world and controlling our daily existence. Where does live theater fit into this? Does it help to restore something we’ve lost, or are in danger of losing?

MC: In many ways, theatre is the art of loss. You know that you are going to experience a set of images and situations for a particular duration. It is an ephemeral art form and performance is notoriously difficult to document fully. Technology has helped in this regard and indeed has become manifest within performance. However, it is the ethereal nature of theatre – the very essence of its ‘liveness’ and the knowledge that no two performances are the same which differentiates it from any other art form and it is what I feel should determine and be the focus of its future.

This is coupled of course, with the fact that it is a symbol of a sort of consensus – it is a rare commitment these days that a large group of people converge together in the same physical time and space for whatever period. If we are in danger of losing this, I think live theatre will not necessarily help to restore physical communication but instead do as it has always done by acting as a meeting point in which people can experience. So if theatre is the art of loss then as Elizabeth Bishop suggests: ‘loose something every day… then practice loosing father, loosing faster.’

LS: Many audiences think of Beckett as a minimalist—sparse language, lots of silence. But in fact, as the title of your recent series, “The Relish of Language,” suggests, words are paramount in his work. What’s distinctive about Beckett’s use of language?

MC: Beckett was the definitive wordsmith. As he says, ‘All I know is what the words know.’ There are many elements that make his use of language distinctive. For example he was acutely aware of the sounds and playfulness of words and invested heavily in their music. This is evident throughout his work for example in the passage in Watt which goes ‘And the poor old lousy earth, my earth and my father’s and my mother’s and my father’s father’s and my mother’s mother’s and my father’s mother’s and my mother’s father’s and my father’s mother’s father’s’ and so on.. This is a real gift to a performer.

Equally in Not I, the speed at which words should be spoken are determined by an entire passage of broken structures. Often it is what Mouth does not say that is important and indeed Beckett was very faithful to silence. In Not I we hear the edits of speech, we are brought into the conception of language and we are made very much aware of its construct but at the same time through the speed of its delivery the meaning becomes less important and we are left with the musicality of the speech. Beckett too, often comments on the act of writing during the process of writing itself and this is evident in Endgame when Clov asks Hamm ‘What’s keeping us here?’ To which he replies ‘The dialogue.’ It is back to the notion of acknowledgement, of fallibility. We are always aware that what we are hearing has been written even to the extent that writing is criticized as in Watt ‘how hideous is the semi-colon?’

LS: You’ve been producing Beckett for more than 20 years. How has audience reception of his work changed during that time?

MC: In actual fact it has been 30 years – I am often mistaken for a much younger man! I think Beckett’s first audiences may have been focused on discovering a fixed meaning or identifying a particular line of understanding which was offset considering the climate of art and such works as those by Rothko or Jackson Pollack. I think that investigation, while not having disappeared completely, has definitely relaxed somewhat and audiences now experience the work on a sheer level of enjoyment.

LS: You’ve been described as a “ready apostle” for Beckett, with a missionary’s zeal for promoting his work. Is this still your primary aim in presenting him?

MC: I would not identify with the martyr connotation of the question. I have simply promoted his work for so long because the work itself is that good. One does not recommend something for no reason. When you are drawn to a work or any experience in life it is the greatest joy to share that. I firmly believe that Beckett is the greatest writer of the 20th century and testimony to that, is that a play like Endgame written fifty-five years ago has all the rigor and courage of a new play. This makes my job very simple.

LS: Born Irish, Beckett spent his adult life in Paris and wrote his plays first in French. What does it mean for an Irish company to present his work?

MC: While I believe that one element of Beckett’s genius is that his work is, in effect timeless and placeless which gives it its universality, I do believe there is a lyricism in the language that is inherently Irish. While it is not a pre-requisite to staging his work, I think there are subtleties such as expressions and syntax that are fully illuminated with an Irish voice. Indeed Beckett was a fan of Barry McGovern’s voice which has become synonymous with his work. Krapp’s Last Tape is a specific example of this, with lines such as ‘went to Vespers once like when I was in short trousers’ and ‘Be again in the Dingle on Christmas eve.. be again on Croghan..’

Beckett asks a lot from actors, to put it mildly. He sticks them in garbage cans and buries them in sand up to their necks. He calls for huge feats of memorization. Ann Arbor audiences will see Barry McGovern, for example, perform Watt solo for more than an hour. How do actors do it? Don’t they wind up thinking him a sadist?

I think what Beckett asked of the actor was total embodiment. Indeed he was as much a director and choreographer as he was a writer. Yet, however much the actor was restricted in terms of physicality or delivery in terms of the speed of speech, there is in fact great freedom in restraint and Beckett’s allegiance to silence was a generous gift to any actor to transpose their own music and physicality within the spaces he deliberately laid vacant for them. As he put it, the task of the artist is to find a form that accommodates the mess.

The audacity of WATT

“If we can’t keep our genres more or less distinct, or extricate them from the confusion that has them where they are, we might as well go home and lie down.” This is a clearly unamused Samuel Beckett, protesting to his American publisher Barney Rosset that his play Act Without Words absolutely must not be filmed. In another missive to Rosset, referring to his radio play All That Fall, Beckett sounds even more unequivocal: “I am absolutely opposed to any form of adaptation with a view to its conversion into ‘theatre’…to ‘act’ it is to kill it.”

“If we can’t keep our genres more or less distinct, or extricate them from the confusion that has them where they are, we might as well go home and lie down.” This is a clearly unamused Samuel Beckett, protesting to his American publisher Barney Rosset that his play Act Without Words absolutely must not be filmed. In another missive to Rosset, referring to his radio play All That Fall, Beckett sounds even more unequivocal: “I am absolutely opposed to any form of adaptation with a view to its conversion into ‘theatre’…to ‘act’ it is to kill it.”

This is certainly one way to underline the audacity of Barry McGovern’s solo-performance distillation of Samuel Beckett’s novel Watt, coming to the stage this weekend as part of Gate Theater Dublin’s visit to Ann Arbor. In its original form, Watt, Beckett’s spare, hilarious, and bizarre black comedy—written during World War II but deemed unpublishable until 1953—is a 250-page narrative puzzle with its own idiosyncratic internal rhythm and strength of purpose. The novel even ends, cheekily, with the statement “No symbols where none intended,” as if to ward off any independent-minded future interpretations.

So yes, Beckett preached genre purity, even if he didn’t always practice it. (He gave grudging permission for others to adapt his work, and occasionally even supervised such adaptations.) But, in his book Samuel Beckett: Repetition, Theory and Text, critic Steven Connor notes a “principle of transferability” at work in Beckett’s prose, especially in his later years, after he had begun writing medium-specific works for television and radio:

The close attention to details of space and position in the related texts…as well as the theatrical language often used in these works, often suggests a doubling of medium, as though the texts included within themselves the possibility of their staging in some other theatrical form.

Anyone who has seen Beckett performed knows this to be demonstrably true. The chilly nakedness of his prose, his elemental plotting, and an aesthetic that suggests the abolishment of space and time, have always lent themselves to imaginative interpretation. A 2008 Gate Theater staging of Eh Joe, which Beckett originally wrote for television, stranded a silent Liam Neeson alone onstage, listening to a woman’s recorded voice, while a big screen behind him displayed an increasingly magnified live video image of his face. Director Atom Egoyan, the celebrated filmmaker, conceived of the idea when realizing that Neeson’s role is “the longest reaction shot than an actor can imagine.”

If, per Watt, “to elicit something from nothing requires a certain skill,” then eliciting something from something else requires, at the very least, a kind of reckless ambition. If adapting from the page to the stage, this eliciting might compel an attendance to the visuality of the text. For Raymond Federman, the French-American writer and academic who made his career at the University of Buffalo—and died in 2009—Beckett was less a writer than “a great painter…who painted tableaux (or tableaus) with words.” In his 2000 lecture “The Imagery Museum of Samuel Beckett,” he encouraged readers to look at Beckett’s books “like tourists look at paintings on the walls of a museum or exhibit.” Federman finds Watt to be “full of such absurd surrealistic pictures,” and discovers within the novel a description of a quite literal painting, hanging on the wall in Erskine’s room, that Federman suggests as “Beckett’s best explanation of his own work.” Watt, who knows nothing about painting and nothing about physics, narrows down his own understanding of the painting’s content—to say nothing of its potential symbolism—to the following possibilities:

“a circle and its centre in search of each other,

or a circle and its centre in search of a centre and a circle respectively,

or a circle and its centre in search of its centre and a circle respectively,

or a circle and its centre in search of a centre and its circle respectively,

or a circle and a centre not its centre in search of its centre and its circle respectively,

or a circle and a centre not its centre in search of a centre and a circle respectively,

or a circle and a centre not its centre in search of its centre and a circle respectively

or a circle and a centre not its centre in search of a centre and its circle respectively…”

We might as well go home and lie down.

[VIDEO] Cloud Gate Dance Theatre of Taiwan

In a long-awaited performance, Cloud Gate Dance Theatre of Taiwan presents Lin Hwai-min’s newest work, Water Stains on the Wall, on October 21 & 22 at the Power Center.

Below, Cloud Gate Dance Theatre of Taiwan in the words of Ann Arbor’s Taiwanese community.

And an interview with Artistic Director Lin Hwai-min upon his arrival in Ann Arbor:

And a little bit more about his inspirations:

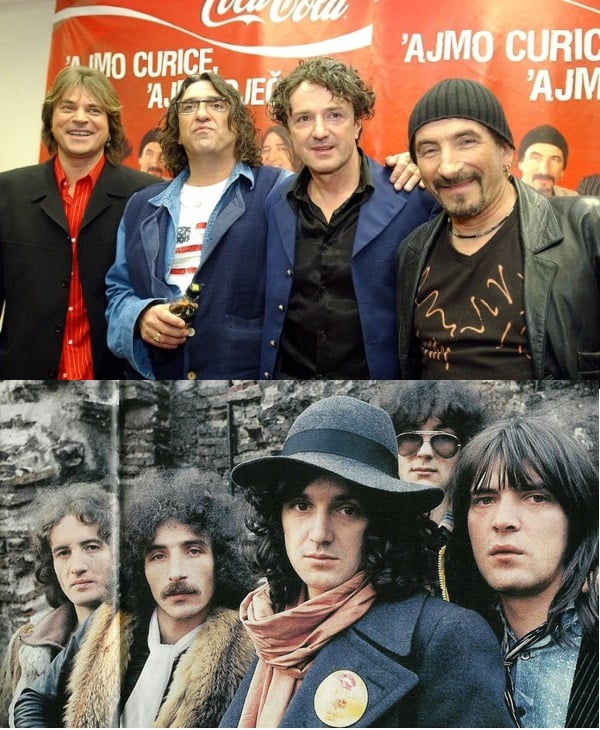

My next-door neighbor, Goran Bregovic

Then: Goran Bregovic and Bijelo Dugne.

It is serendipitous, even ironic, that here in Ann Arbor, Michigan I will see perform, for the first time, my neighbor from Sarajevo. Balkan music icon and acclaimed film composer Goran Bregovic, and his band the Wedding and Funeral Orchestra, one of the most spectacular performing acts to emerge from the Balkans in generations, are coming to the University Musical Society Hill Auditorium this Saturday, October 15.

Much has been said about Goran’s creative oeuvre, the spectrum of his talents and extraordinary music which blends robustly earthy dance tunes infused with brass and string arrangements, with Eastern European choral music ripe with the profound luster of sentimentality. This is going to be an electrifying, ecstatic musical spectacle. This concert is not to be missed, and I cannot wait to be there this weekend. In light of this visit and my own excitement, there is a story, as strange as it is sincere, that I wish to share with you.

It may not be commonly known outside of the Balkans that Goran was the founder and leader of Bijelo Dugme, or White Button band. Widely considered to have been the most popular rock band in what was at the time the Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia and one of the most influential musical acts of the Balkan rock ‘n roll scene, Bijelo Dugme drew critical attention and public frenzy unlike any other band. In the post-Josip Broz Tito Yugoslavia of the 1980s, Bijelo Dugme’s music transcended cultural and political boundaries and arguably brought the rich fabric of the region’s life and culture much closer together than any political leader ever could. Goran’s larger than life persona attracted attention from across the spectrum. He was grand, and to the teenager I was at the time, almost mythical, like Johnny Cash or John Lennon.

In the mid 1980s, Goran, or as people in Sarajevo used to call him, Brega, moved to an inconspicuous apartment building in an old and eclectic working class neighborhood called Mejtas. Mejtas, like many Sarajevo neighborhoods was diverse, an almost dream-like world which was the home to a little bit of everything. Small residential houses dating to the Ottoman period, mixed with Habsburg architecture of the fin-de-siècle, and Josip Broz Tito’s era socialist style apartment buildings. An old Sunni mosque, with its crooked minaret stood a short walk from an old Sephardic synagogue, and the Queen of Rosary Catholic Church. Goran lived at 14 Cekalusa Ulica, which in my native language means the waiting street. I lived at 18 Cekalusa Ulica.

It was the most exciting, bizarre thing I could imagine. I passed him regularly on the street and always mumbled zdravo Brega, hello Goran, before rushing toward my front door to avoid the embarrassment. I can’t imagine Goran noticed this confused kid living next door. Everybody in the Mejtas neighborhood would have said hello to him because that is the way it was. The older and bigger Mejtas kids were punks, notorious on Cekalusa Ulica, especially down near the old Synagogue, where they hung around a small kiosk which sold cigarettes, newspapers, chewing gum and such things. They teased all the younger kids and would have made it impossible for me to walk down my own street if they knew of my attempt to be chummy with the famous neighbor.

Like all teenagers I dabbled in rock ‘n roll music. While attending high school, I formed a rock band but we never performed. My proximity to my famous neighbor may have intensified my desire for stardom, but I was just a kid and had to find my own way. It was around this time a friend suggested we audition for a folkloric dance orchestra KUD Miljenko Cvitkovic as band members, a gesture I looked at with misgivings. To a 15-year old, playing traditional folklore music was as unhip to the point of being tragic. I nevertheless tag-a-long, a decision that profoundly affect my life and career, and those around me.

Now: Goran Bregovic at Eurovision 2008.

KUD, an abbreviation of Kulturno Umjetnicko Drustvo, cultural artistic society, was a typical Yugoslav institution formed following the Second World War in the early days Socialist Federative Republic Yugoslavia. In his effort to promote bratstvo i jedinstvo, brotherhood and unity, an official policy of inter-relations between all Yugoslav nationalities, Josip Broz Tito encouraged the formation of artistic societies in which youth would interact. While material goods were not readily available in the aftermath of the Second World War, everybody could sing and dance. There was an undeniably rich diversity of musical traditions throughout Yugoslavia.

The eclectic diversity of Sarajevo, and perhaps my own youthful age, could not help me fathom the complex twists and turns of post-Tito’s-death Yugoslavia (Tito died in 1980), let alone imagine the fall of this extraordinary society. Between my short-lived fascination with my famous next-door neighbor and the collective realization of the looming storm approaching the country, I was lost in my own youthful magic and enchanted by the musical traditions of the Balkans: from Bosnian Muslim sevdalinka (slow blues songs) and Sopska petorka kolo (an intensely fast dance from the region of Southern Serbia and Northern Macedonia), to Kosovo Rugova (a solemn Albanian tap dance without music), and tamburaske pjesme (string arrangements of the Slavonia region of Northern Croatia). Between 1985 and 1989, I traveled with KUD Miljenko Cvitkovic and performed at folklore music festivals throughout all six Yugoslav republics, the Balkans, Western Europe, and the Middle East, and subsequently discovered a world rich in meaning and full of promise. I left Yugoslavia in the spring of 1990 and took in my heart, an amalgam of these voices and sounds.

Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the melting pot of the Balkans and Goran’s birthplace, was the blueprint of what was once Yugoslavia. Goran never forgot that. His extraordinary music, his life’s work, guides rather than manipulates, like a voice which tells us to open a window into the everyday reality of a different world. That’s where I will be this Saturday. With my neighbor.

UMS on Film Series

Every summer, we come up with about three dozen companion-films to the UMS main-stage season. We’ve narrowed the list to five this year – two in the fall, and three in the winter. Each expands our understanding of artists and their cultures, and reveals emotions and ideas behind the creative process.

In the fall, the films highlight deep cultural expressions which grow from communities of shared heritage. In the winter, the films tie in with UMS’s PURE MICHIGAN RENEGADE series, which focuses on artistic innovation and experimentation. We’ve created a mini film festival, Pure Michigan Renegade on Film, to extend the renegade idea and explore other artists who have created new arts frontiers.

In the fall, the films highlight deep cultural expressions which grow from communities of shared heritage. In the winter, the films tie in with UMS’s PURE MICHIGAN RENEGADE series, which focuses on artistic innovation and experimentation. We’ve created a mini film festival, Pure Michigan Renegade on Film, to extend the renegade idea and explore other artists who have created new arts frontiers.

All films (except one! see below) are presented in the U-M Museum of Art Stern Auditorium (525 S. State Street) and are free and open to the public.

Pure Michigan Renegade on Film:

Helicopter String Quartet

(1995, Frank Sheffer, 81 min.)

Wednesday, March 7, 7:00 PM at the Michigan Theater (603 E. Liberty)

Tickets: $10 general admission; $7 students/seniors/UMS and Mich Theater members; $5 AAFF members

Purchase Tickets Here

The UMS Renegade on Film series culminates at the Michigan Theatre in collaboration with the Ann Arbor Film Festival (celebrating its 50th anniversary in March 2012!!). The curators at AAFF chose an amazing documentary that captures the renegade spirit and provides a fabulous lead-in to the San Francisco Symphony American Mavericks concerts. In one of the most certifiably eccentric musical events of the late 20th century, German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen designed and executed the performance: four string quartet members playing an original piece by Stockhausen in four separate helicopters, all flying simultaneously. The sound was then routed to a central location and mixed; the work premiered, in turn, at the 1995 Holland Festival. Frank Scheffer’s film Helicopter String Quartet depicts the behind-the-scenes preparations for this event; Scheffer also conducts and films an extended conversation with Stockhausen in which the creator discusses the conception and execution of his composition and then breaks it down analytically. Featuring music by Karlheinz Stockhausen, performed by the Arditti String Quartet. Co-presented with the Ann Arbor Film Festival in partnership with the Michigan Theater, in collaboration with the U-M Museum of Art.

Past Films…

Fauborg Tremé: The Untold Story of Black New Orleans

(2008, Dawn Logsdon, 69 min.)

Tuesday, October 11, 7 pm

Connected with UMS’s presentation of A Night in Tremé: the Musical Majesty of New Orleans, this documentary follows Lolis Eric Elie, a New Orleans newspaperman on a tour of his city, a tour that becomes a reflection on the relevance of history, folded into a love letter to the storied New Orleans neighborhood, Faubourg Tremé. Arguably the oldest black neighborhood in America and the birthplace of jazz, Faubourg Tremé was home to the largest community of free black people in the Deep South during slavery, and it was also a hotbed of political ferment. In Faubourg Tremé, black and white, free and enslaved, rich and poor co-habitated, collaborated, and clashed to create America’s first Civil Rights movement and a unique American culture. Wynton Marsalis is the executive producer of the film, which also features an original jazz score by Derrick Hodge. Introducing the film is U-M American Culture faculty member Bruce Conforth, whom some may remember from last season’s series on American Roots music.

AnDa Union: From the Steppes to the City (with director Q&A)

(2011, Sophie Lascelles and Tim Pearce)

Tuesday, November 8, 7 pm

Before AnDa Union takes the stage at Hill Auditorium, filmmakers Sophie Lascelles and Tim Pearce will screen their new documentary, which follows the group of 14 musicians who all hail from the Xilingol Grassland area of Inner Mongolia. The film premieres at the London Film Festival on October 13, and Ann Arbor will be one of the first to screen it after its debut. AnDa Union is part of a musical movement that is finding inspiration in old and forgotten folk music from the nomadic herdsman cultures of Inner and Outer Mongolia, drawing on a repertoire of music that all but disappeared during China’s recent tumultuous past. Tim and Sophie will be here in Ann Arbor to introduce the film, and take audience questions after the screening.

Absolute Wilson

(2006, Katharina Otto-Bernstein, 105 min.)

Tuesday, January 10, 7 pm

Absolute Wilson chronicles the epic life, times, and creative genius of theater director Robert Wilson. More than a biography, the film is an exhilarating exploration of the transformative power of creativity – and an inspiring tale of a boy who grew up as an outsider in the American South only to become a fearless artist with a profoundly original perspective on the world. The narrative reveals the deep connections between Wilson’s childhood experiences and the haunting beauty of his monumental works, which include the theatrical sensations “Deafman Glance,” “Einstein on the Beach” and “The CIVIL WarS.”

The Legend of Leigh Bowery (with director Q&A)

(2002, Charles Atlas, 60 min.)

Monday, February 13, 7 pm

Renegade filmmaker Charles Atlas (who worked extensively with the late choreographer Merce Cunningham) introduces his 2002 documentary The Legend of Leigh Bowery. Artist/designer/performer/provocateur Leigh Bowery designed costumes and performed with the enfant terrible of British dance Michael Clark, designed one-of-a-kind outrageous costumes and creations for himself, ran one of the most outrageous clubs of the 1980s London club scene (later immortalized in Boy George’s Broadway musical “Taboo”), and was the muse of the great British painter Lucian Freud. The film includes interviews with Damien Hirst, Bella Freud, Cerith Wyn Evans, Boy George, and his widow Nicola Bowery. Charles Atlas will participate in audience Q&A immediately following the film. This film is co-presented with the U-M Institute for the Humanities which hosts Charles Atlas’s video installation “Joints Array” in February 2012.

Performances for the Whole Family: Filling the master calendar with UMS events

Part of the excitement of coming back to town at the end of summer is collecting all the calendars—Ann Arbor Public School’s holiday and half-day calendar, Huron High School’s band calendar, Clague Middle School’s orchestra calendar, King Elementary School’s PTO calendar, the crew calendar, the soccer calendar, the academic games calendar, University of Michigan’s football calendar, Washtenaw Community College Lifelong Learning calendar, Rec and Ed, Parks and Rec, etc.—whew!—and finally sitting down to map them all out onto one big master calendar in order to see what our year is going to look like.

Part of the excitement of coming back to town at the end of summer is collecting all the calendars—Ann Arbor Public School’s holiday and half-day calendar, Huron High School’s band calendar, Clague Middle School’s orchestra calendar, King Elementary School’s PTO calendar, the crew calendar, the soccer calendar, the academic games calendar, University of Michigan’s football calendar, Washtenaw Community College Lifelong Learning calendar, Rec and Ed, Parks and Rec, etc.—whew!—and finally sitting down to map them all out onto one big master calendar in order to see what our year is going to look like.

My favorite calendar to pore over with the kids is the one from University Musical Society (UMS).

This year, the University of Michigan Center for Chinese Studies is celebrating its 50th anniversary. As usual for an academic department, they have all sorts of lectures and films and special events and conferences planned. University of Michigan Museum of Art is supporting this celebration with a contemporary Chinese woodblock print exhibit. University Musical Society is supporting this celebration with an Asia performance series. I am excited.

When the UMS catalog arrives, the kids keep grabbing it away from one another. They dog-ear the pages that interest them. They recall other concerts and dance performances we have attended.

Little Brother is captivated by the photograph of the old woman and old man sitting in trashcans. What could that possibly be? (Gate Theatre of Dublin) How to explain Beckett’s “Endgame” and “Watt” to a seven year old?

Our pianist, Niu Niu, complains (again) that she likes playing piano but does not like watching piano, but when we begin discuss how the dazzling Yuja Wang recently rocked the Hollywood Bowl with her very short very tight very sexy orange dress, about which reviewer Mark Swed wrote: “Her dress Tuesday was so short and tight, that had there been any less of it, the Bowl might have been forced to restrict admission to any music lover under 18 not accompanied by an adult.” Oh, and her legendary speed, too. Now Niu Niu is convinced. Our first concert marked on the calendar.

Cloud Gate Dance Theatre of Taiwan is my choice. I have already heard many Taiwanese American friends discussing how the choreography is inspired by Chinese calligraphy and classical landscape painting. Local Chinese calligraphers will be demonstrating and displaying their work before the performance to connect these two artforms.

Hao Hao wants to go see AnDa Union from Inner Mongolia. I thought it was because her great-grandfather was born in Inner Mongolia, but really it is because she remembers the Mongolian throat singers we once heard perform at the Ann Arbor District Library.

M is intrigued by the Chamber Ensemble of the Shanghai Chinese Orchestra because she knows more about Chinese music than any of us, but the Ballet Preljocal looks amazing. An antithesis of Disney’s Snow White? It looks dark and grim and sexy and strange—irresistible for teenagers dressed all in black.

Now, big sigh, the tickets.

I was so grateful when UMS began their teen ticket program a few years ago, at last an affordable way to bring my teenagers to UMS programs. I was even more grateful when I was able to go with the children’s school field trips as a chaperone. This year, UMS is launching a new UMS “Kids Club” program for students in grades 3 to 12: “Two weeks before opening night, parents can purchase up to two kids’ tickets for $10 each with the purchase of an adult ticket for $20.”

Great! So now we can take the whole family.

Q&A with piano sensation Yuja Wang

We asked you to send us your questions for pianist Yuja Wang. Her answers are below. Yuja is performing at Hill Auditorium on Sunday, October 9.

We asked you to send us your questions for pianist Yuja Wang. Her answers are below. Yuja is performing at Hill Auditorium on Sunday, October 9.

Q: You’re often described as a young piano prodigy. How do you think your youth affects your performance?

If there is any effect, I think it’s unconscious or subconscious, but the pieces I learned when I was say, before 16, I would never forget, they just stick with you your whole life.

Q: Can you talk a little about how you put together your programs? What’s your dream program?

Programming is an art and I get inspired by the menus in Japanese restaurants. Variety and unity are key for me now.

Q: What composer or work do you find most challenging to play? Do you view that as a good thing?

I only play the works in public when I think I can handle it. Playing, perceiving, understanding, internalizing a work sometimes requires a lifetime, it changes when our point of view of life changes, it’s something that stays with your life, something that counts in the end.

Q: What’s one piece of advice that you could pass on to other young aspiring musicians?

Go with the flow, be creative, transcend to something more cosmic.

VIDEO: Center for Chinese Studies New Millennium Kite Festival

Our Asia Series starts with Yuja Wang on October 9th.

This weekend, Center for Chinese Studies, inspired by the traditional Asian craft of kite flying, presented a one-day jubilee with a community competition, master kite fly-offs, lion dancing, and wind-borne activities, including a DIY kite workshop on September 25. Check out the fun:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Opxj6G5kTo8