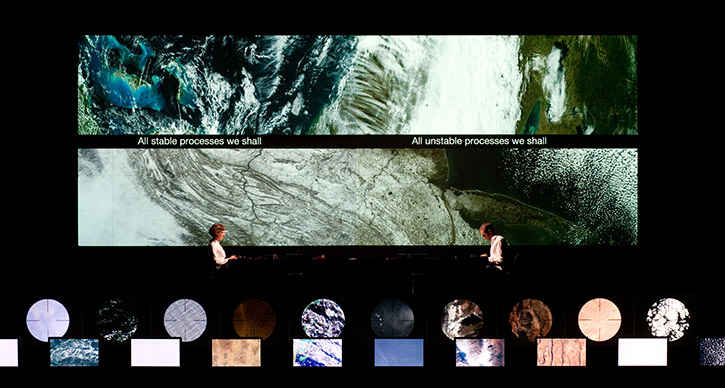

Artist Statement: Javaad Alipoor on ‘Things Hidden’

Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World is the final part of a trilogy of shows that began in 2017. At the heart of this trilogy has been a single thread: the relationship between contemporary technology and contemporary politics.

My idea was that the relationship between contemporary technology and contemporary politics is revealing things about how our minds work, and that to try and get to grips with what is going on in the world today, we have to understand, at the same time, how we train ourselves to think about them.

Each part of the trilogy has tried to refract this idea through different lenses. The Believers Are But Brothers, the first part of the trilogy, used instant messaging technology like WhatsApp to think about masculinity, extremism, and the Internet. Rich Kids: A History of Shopping Malls in Tehran used Instagram and video messaging to explore the Anthropocene, the growing gap between the rich and the poor, and the collapsing promise of the 20th century’s moments of revolution. This final part uses Wikipedia and murder mystery podcasts to confront the way the world seems to be moving closer together, at the same time that we find it harder and harder to understand each other.

At its heart is a true story. The unsolved murder of Fereydoun Farrokhzad, an iconic Iranian pop star, living as a refugee in Germany in the early 1990s.

When I first began work on it in the middle of the pandemic it had a certain context. At its heart, it’s a piece about the responsibilities that people in richer and more democratic countries have towards people and countries who are fighting for more democracy. And this necessitates it also being about translation. Too often, people in our part of the world, problematically grouped together as the West, use the rest of the world as examples that flesh out their preconceived ideas about how things work.

On the right they want to claim that the world would be fine if everyone followed their example; and on the left they want to say that the West is the font of all evil. But the reality of the countries at the forefront of this struggle, whether Iran, Hong Kong, Syria, or Ukraine, is that they upend such preconceived notions. It needs to stop putting ourselves at the center.

So while Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World is in part a sort of protest song about the murder of Fereydoun Farrokhzad, it’s also about how we try and process stories like that.

It’s about the possibility of political and social solidarity in a world of superhuman complexity and interconnectedness. It’s about the thousands of ways that our brains, our devices, and our histories seduce us into simplification or terrify us into inaction. It’s about the feeling of being both overstimulated and stuck, and it’s about the bravery we need to abandon all that.

As the trilogy has developed, the level of ambition that I’ve tried to bring to it has grown, too. Collaboration has been key to all these works, and in this show, the team has been bigger and more talented than ever before. As well as the performers and creatives you see on stage and operating the show, the project would not have happened without the initial conversations I had with my co-creator, dramaturge, and partner Natalie Diddams. The co-writing relationship with Chris Thorpe that resulted in the script we perform has come out of five years of working together.

The first part of this trilogy received its US premiere here at Ann Arbor as part of the No Safety Net festival in 2020, and so it feels like an honor to share this final part with the unique community around UMS.

— Javaad Alipoor

Experience Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World, Nov 15-18 at the Arthur Miller Theatre.

Artist in Residence Spotlight: Making Art and Making a Point

This post is a part of a series of posts from UMS Artists in Residence. Artists come from various disciples and attend several UMS performances throughout the season as another source of inspiration for their work. In this post, UMS Artist in Residence Morgan Breon reflects on the UMS presentation of Us/Them.

This post is a part of a series of posts from UMS Artists in Residence. Artists come from various disciples and attend several UMS performances throughout the season as another source of inspiration for their work. In this post, UMS Artist in Residence Morgan Breon reflects on the UMS presentation of Us/Them.

Morgan Breon is a performing and literary artist. She’s an ensemble member of Shakespeare in Detroit and the Detroit Repertory Theater. Morgan’s play “A Kiss of the Sun for Pardon,” which she wrote at the age of 13 and reprised 13 years later, received the award for “Audience Favorite” at the 2015 Two Muses Women’s Playwriting Festival and the “Jury Award” at the 2015 Detroit Fringe Festival. Morgan received a dual Bachelor of Arts and dual Masters from the University of Michigan, none of which are in theatre. Her degrees reflect her passion for youth, social justice, as well as individual and community healing. These principles influence Morgan’s work as an artist, and guide her use of the arts to impact community. Morgan credits Jesus Christ with her gift of anything creative.

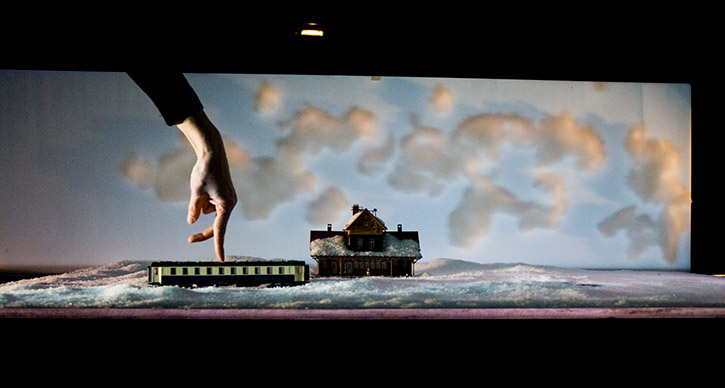

Walking into the Arthur Miller Theatre, the ambiance alone put me in a good mood. The quaint yet majestic theatre provided an additional element in setting the tone of: safety and intimacy. Which is often equally as desirable for young school-aged children. I was intrigued by the set! All of the pieces of the set were reminiscent of child’s play and/ or child mentality: chalkboard painted with a blue sky, sidewalk chalk lined up against the backboard, coat hooks, seatbelts extended from the sky, and a unique bouquet of black balloons. Yes, I was definitely intrigued. And no action had happened yet! But once the play started, the audience was immediately thrusted into the lives of two characters: a boy and a girl, who on thinking about it, I don’t think we ever got their names. Hmmm. (This may be intentional. But it may not. I could see arguments for both.)

During the play, I found myself engaging with the piece on multiple levels. As an actor, I thought both actors did a great job of using movement and their interpretation of the words to depict “child-like mentality.” There were very few moments where the characters weren’t in competition with each other, doing whatever was necessary — refreshing and familiar ways — to outdo the next one. (Which I loved!) This component imprinted a permanent smile on my heart, as I tend to thrive on authenticity and acute richness in my own work. My obsession was piqued by many more of these moments, such as the characters engaging in extra dialogue that often took them “out of the character” and added to their humanness.

As an artist, in general, I found myself especially inspired by the “minor details.” At one point the male actor wiped ketchup off of his face and flicked it. (Imaginary ketchup, mind you.) And guess what? The female actor responded to it! It was so subtle, but a reminder to me as an artist to challenge myself in the “details” of my artistry. Often times, I can get so caught up on the “general objective” of a project that I lose sight of basking in the details. Even the sporadic and simplistic “countdown” of the characters: “149…147…136,” indicating the number of people dying during the story was a powerful “detail” that, if left out, wouldn’t have been noticed but, being put in, provided a device that enhanced the overall impact of the play.

Yes, I was very pleased with the performance, but my “dilemma” arose after the performance when my social worker lens was applied and I started thinking about what I had just seen…and what it meant exactly. As of today, I’m still not sure. Don’t get me wrong, the performance was moving, but upon learning that it was created for nine-year-old children, my follow-up question was: to do what? During the discussion afterward, someone commented that a piece as “edgy” as Us/Them would never be shown to American nine-year-olds. I agree. But ignorance would be the culprit behind that decision — mistakenly thinking that a play inspired by violence would automatically be violent. So, this is a moot point.

As a creative, I would want nine-year-olds and above to see this because it would lead to questions, which could turn into discussion…but this may be a far reach. The reason I wouldn’t want to show it to nine-year-olds is because, in my opinion, the play sends a miscue about how to cope with trauma — especially for American children (who look like me) who experience trauma at multiple levels. As a social worker, this piece would set a young person’s treatment backward because the main message I saw was: “don’t show emotion” and/or “talk about what’s happening…without actually talking about it.” And in all honesty, too many Americans do too much of this already. The “emotionalism” that underscored the performance was provided by the audience’s foreknowledge of what the play was about. The characters never addressed how they felt. Which, may be an argument that kids rarely know how they feel (especially nine-year-olds).

But isn’t that the point? Don’t we want to get better at helping our children identify their emotions, so they won’t have to use yellow-faced and electronic emojis to express it for them? Don’t we want to aid them in identifying the root of their reactions, instead of unproductively addressing the actions themselves? I think the answer that Us/Them provides to this question is: “Ummm” (shrugging emoji). Overall, I think the artistry of the play itself motivated me to be a more responsibly detailed artist. The intended goal of the piece, however, reminded me of how important it is to either make art, or make a point. And if you aim to do both, make sure one feeds the other.

Follow this blog for more updates from Morgan throughout this season. Learn more about Renegade this season.

On Being African at the University of Michigan

Moment in portrait of myself as my father. Photo by Gennadi Novash.

Nora Chipaumire’s portrait of myself as my father is a piece of many origins. All aspects of Chipaumire’s identity as an African, a woman, a black woman, an African woman, and an African-American woman seep into her work. In this “love letter to black men,” she explores the complex tangle of conceptions, stereotypes, expectations, vulnerabilities and strengths of the black African male.

Zimbabwean influences, unique venue

A dizzying combination of Zimbabwean and African dance traditions, garb, and music help to tackle these big questions. Traditional Zimbabwean music rooted in polyrhythmic beats combines with Zimbabwean dance, an art form which requires a considerable amount of strength and agility to perform. Chipaumire uses these tools to celebrate the strength, resilience, and inherent defiance of the black body. She fuses her Zimbabwean heritage with her contemporary dance training to create this piece. Wearing traditional African gris-gris (a talisman used in Afro-Caribbean cultures for voodoo) with football pads, Chipaumire explores the black male at the crossroads of two cultures and identities.

Nora Chipaumire in portrait of myself as my father. Photo by Elise Fitte Duval.

The piece is set in a boxing ring and will be performed in at the Detroit Boxing Gym, where a program to support kids living in Detroit’s toughest neighborhoods is based and focuses on helping young black males find fruitful after-school activities to grow and develop real-life skills with positive role models.

It is not only a fitting location for Chipaumire’s exploration of black masculinity in a postcolonial world but also serves as a perfect setting for her vigorous, high-energy performance. Chipaumire has also spoken out about the brutal policing of black sexuality and masculinity, and celebrates her heritage through her art.

On Being African at the University of Michigan

African students at the University of Michigan have a unique perspective on the challenges and stereotypes Africans experience in America. Tochukwu Ndukwe, a Nigerian-American kinesiology student born in Nigeria and raised in Detroit, spoke about how his identity as a Nigerian-American student informs his experiences at the University of Michigan. In a school that is overwhelmingly white (a mere 4.4% of the population is Black or African-American), he immediately stands out.

In fourth grade, Ndukwe met a Nigerian student who embraced his culture unapologetically. This student was unafraid to educate other students about why he brought a different kind of lunch to school, or the differences between his how his parents raised him in an African household. Ndukwe was inspired by this classmate, but did not to truly publicly embrace his culture until high school. Torn between wanting to fit in with other black students and wanting to celebrate his culture in public, Ndukwe was both surprised and excited by the strength, unity, and pride of African students at the University. He now serves as president of the African Student Association (ASA), an organization that arranges cultural shows, potlucks, and mixers with other ethnic organizations on campus. Their flagship event is the African Culture Show, a massive celebration of African music and dance that packs the Power Center every year. This year’s show is titled Afrolution: Evolution of African Culture, an inquiry into the future of Africa by African students.

Ndukwe lauds African music as a crucial tether for African students to relate to the culture in their home country. He says that music allows African students to connect with their culture no matter where they are, which is especially important in Ann Arbor, which lacks the music, values, and language of their home countries.

“African music and dance are becoming more and more American,” Tochukwu says. “People there look up to America, they want to be American. African artists are beginning to collaborate with American artists, and I’m like ‘No, don’t lose your culture! It’s so rich!’” Africans are bombarded with American media and feel an increasing pressure to conform music and dance styles to that of American–particularly black American–culture, Ndukwe says.

A very loaded question

We begin discussing gender norms in Nigerian societies (he says many of the Nigerian gender norms are found throughout Africa) and a broad smile spreads across his face. “Oh, boy…you’ve asked me a very loaded question. I don’t even know where to start.”

He says, “African men are expected to be the breadwinners. They’re supposed to be strong, stoic, devoid of vulnerability. They are expected to be the disciplinarian of the family while women are expected to stay home…cook, clean, care for the children.” He explains that the expectation for men to be “macho”, and “hypermasculine” oppresses women, and that the division between genders prohibits women from getting an education and becoming financially independent.

“Mental health hasn’t even begun to be a topic in the general cultural discourse. There’s no such thing as depression, as anxiety for anyone, let alone men. So many men suffer in silence because of it.” As pressures mount for men to be sole breadwinners, disciplinarians, protectors of the family–stoic and strong–many men are subsequently unable to express their emotions with the women they care about. Ndukwe’s background as a Nigerian-born man raised by Nigerian parents tightly bound to their culture informs his relationship with women today. On a personal note, he says that he struggles to express his affection with his significant other. This leads to gaps in communication and rifts in his relationships that are often difficult to repair.

portrait of myself as my father comes at an especially important time. As the consequences of the narrow and stereotypical perception of black men enter the mainstream consciousness, this piece opens the door for discussion.

How does the representation of the black body impact the perception of self as a black woman, an African woman, and an American woman? How has colonialism seeped into the treatment of the black performing body?

Nora Chipaumire asks and investigates these questions in portrait of myself as my father.

See the performance November 17-20, 2016 at the Detroit Boxing Gym in Detroit.

Resident Update: Artist Carolyn Reed Barritt on Compagnie Non Nova

Painter Carolyn Reed Barritt is a UMS Artist in Residence this season. We’ve asked five artists from across disciplines to take “residence” at our performances and to share the work these performances inspire.

Carolyn attended Compagnie Non Nova‘s performance of Afternoon of a Foehn this past weekend at Skyline High School’s black box theatre. She shares her thoughts on the performance:

“I didn’t think I could be so enraptured by ordinary plastic bags…The performance is mastered chaos — each fan controlled to create an airflow which allows the bag puppets to twirl, float and wrestle with each other and their creator in a confined space. Sometimes the puppets skate together along the floor; sometimes it seems as though they are tying to escape by floating up to the ceiling. Sometimes they seem to attack each other. Their creator moves with them, allowing them to dance and fight until they turn on him, using the wind that animates them to envelope and smother him with their bodies, making him so angry he destroys them all. The audio track ebbs and flows from sublime to sinister, the bag puppets go from charming to vindictive, the single, silent actor, ghost-like and imperious — all this in a home-made wind vortex.

If you’re lucky enough to be in Ann Arbor Michigan right now, there are more shows this coming weekend (February 19 – 21, 2015). Otherwise I hope this show comes to you someday!”

Read the full post on Carolyn’s blog

Interested in learning more? Read our interview with Carolyn.

The State of Theater in Ann Arbor: Looking Back to 2000, and Looking Ahead

Editor’s note: This article initially appeared in the Ann Arbor Observer in October 2000 and offers a snapshot of the history of theater in Ann Arbor and major developments in the city’s theater life during this time.

Leslie Stainton is a regular contributor to UMS Lobby, focusing on theater. Her new book Staging Ground captures the history of one of America’s oldest and most ghosted theaters—the Fulton Theatre in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

She participates in an authors panel on January 28, 2015, which also included U-M faculty Martin Walsh and Leigh Woods. While the panel will spotlight Staging Ground, it will also provide an updated look at the state of theater in Ann Arbor today.

We thought this “time capsule” would be a great read ahead of that panel.

Arthur Miller, Lee Bollinger, and the U-M’s dead-serious campaign to bring Ann Arbor back to the theatrical big leagues.

It’s been nearly sixty-five years since Arthur Miller sat in a rented room at 411 North State Street in Ann Arbor and in six days wrote his first play. That work, No Villain, won Miller a Hopwood Award worth $250—half the sum it had cost him to come to Michigan in the first place—and convinced him he had what it took to compete with the reigning Broadway playwrights of his day: people like Clifford Odets, Maxwell Anderson, and Philip Barry.

Today, of course, Miller’s name outshines all the rest. “He’s the greatest living American playwright,” says U-M English prof Enoch Brater. With Eugene O’Neill and Tennessee Williams, Miller created the plays that became the bedrock of American theater. His best-known work, Death of a Salesman, has been performed around the world. Last year’s Broadway revival won four Tony Awards half a century after the play premiered in 1949.

Arthur Miller returns to Ann Arbor this month to give the keynote address at an international symposium honoring him on his eighty-fifth birthday. It’s an auspicious moment in the American theater, nationally as well as locally.

An Up and Down Track Record in Ann Arbor

From New York to California, the commercial stage is thriving. For the first time in years, thanks to a booming economy, every theater on both Broadway and Off Broadway is lit. Big musicals earn huge grosses in New York and spawn profitable touring productions that play to packed houses in places like Toronto and Detroit. Nonprofit theater attendance across the country is also up, according to a 1999 survey by the New York–based Theater Communications Group, as are artist salaries, education and outreach programs, and individual giving. But the costs of producing theater are higher than ever, and competition for arts funding is fierce.

Ann Arbor—whose theatrical track record is at best “up and down,” says Russ Collins of the Michigan Theater—offers a portrait of the art in miniature. Home to one of the oldest university theater programs in the country, the city courted the Guthrie Theater in the late 1950s but lost out to Minneapolis. In the 1960s, under the auspices of the U-M’s Professional Theater Program (PTP), Ann Arbor played host to one of the foremost nonprofit repertory theaters in America, Ellis Rabb’s Association of Producing Artists, or APA. At its heyday in the mid-1960s, the APA earned praise from New York Times critic Walter Kerr as “the best repertory company we possess.” The Times called Ann Arbor “a major regional theater center.”

Since then, it’s been a roller-coaster ride. By 1970 the APA had largely dissolved. The PTP continued to bring in touring shows from the likes of Ontario’s Stratford Festival and John Houseman’s Acting Company, but its visionary co-directors, husband and wife Robert Schnitzer and Marcella Cisney, retired shortly after the construction of the Power Center for the Performing Arts in 1971. In 1973 the PTP was merged into the U-M theater department and placed under the direction of the department chair, a move that further weakened the once maverick organization. “It never got back on its feet again, which is heartbreaking,” says longtime producer, performer, and Ann Arbor theater patron Judy Dow Rumelhart.

Rumelhart herself was involved in a brief attempt to create an outdoor Greek theater festival in Ypsilanti in the late 1960s. The theater’s first and only season starred Ruby Dee, Dame Judith Anderson, and Bert Lahr. But fragile community support, poor leadership, and a deteriorating economic climate doomed the effort.

In the late 1970s Ann Arbor theater aficionado Jim Packard spearheaded an ambitious town-gown endeavor to organize a summer performing arts festival on the scale of Stratford. “I believe it is the manifest destiny of Ann Arbor to become the cultural capital of the region,” Packard said at the time.

But despite an elaborate, two-year planning process that included detailed marketing and feasibility studies, consultations with nonprofit theater professionals throughout the country, and grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, among others, the project foundered—partly because of turf wars between the city and the university, partly because of a statewide recession, and partly because the university was not prepared to market the endeavor on the scale it required. From the spoils of the project, today’s much smaller Ann Arbor Summer Festival emerged.

Twice in the 1980s the U-M tried to establish professional companies in alliance with its theater department, but both efforts—Walter Eysselinck’s Michigan Ensemble Theater and John Russell Brown’s Project Theater—folded after a few seasons. In each case, the department chair was simultaneously artistic director of the professional company, in an arrangement that had already proved unworkable in the early 1970s.

In 1991 Hollywood actor Jeff Daniels opened the Purple Rose Theater in his hometown, Chelsea. In 1996 Ann Arbor’s Performance Network went professional. Both companies are opening new theaters this season, a mark of their prosperity (see sidebar, “Reversals of Fortune”).

But Purple Rose and Performance Network are small companies that present exclusively new plays on modest budgets. Ann Arbor continues to lack the kind of first-rate anchor that a large-budget, nationally visible theater such as the Guthrie in Minneapolis provides.

In a now legendary irony, Sir Tyrone Guthrie toyed with putting his theater in Ann Arbor in the late 1950s but ultimately chose Minneapolis because of its more lucrative business climate. U-M administrators gave Guthrie an initially “cool reception,” remembers Wilfred Kaplan, who was involved in the effort to lure Guthrie to Ann Arbor. That, coupled with a lukewarm response from the Detroit business community, steered Guthrie away from Michigan. “Everyone had to come together, and they didn’t,” Kaplan recalls.

Theater: The Weak Sister

Today, Ann Arbor’s theater scene doesn’t begin to approach its musical and dance offerings in either quality or quantity. In a town that routinely sees the likes of the Berlin Philharmonic, Yo Yo Ma, Mark Morris, and the Martha Graham Company, theater is “the weak sister,” says Russ Collins. Collins attributes the situation to Ann Arbor’s German-immigrant heritage. “Music is strong because the Germans valued it. These social patterns hold sway even when the ethnic relevance has gone away.”

For U-M president Lee Bollinger, theater is the missing link in Ann Arbor’s otherwise rich cultural picture. “We should have theater that is as vibrant as the music that we experience on campus,” he says. A passionate advocate of the arts who carries a copy of Shakespeare with him much of the time and tries to read something from it “almost every day,” Bollinger has put theater at the center of his vision for the university. In fact, the former law professor and dean is the one person with both the imagination and the means to change not only the university’s but Ann Arbor’s theatrical fortunes in a big way, and he seems determined to do it.

At a press conference last spring, Bollinger announced plans to build a Walgreen Drama Center near the Power Center, on the university’s Central Campus. The new complex will include two theaters: a 600-seat Arthur Miller Theater and an as yet unnamed 100-seat space.

During the same press conference, University Musical Society president Ken Fischer announced the launch of the first full-fledged theater season in the organization’s 122-year history. The season, which opens this month, will include appearances by the Gate Theater of Dublin, Harvard University’s American Repertory Theater, and a three-week residency by one of the world’s foremost classical theater companies, the Royal Shakespeare Company. The season ends next April with a performance piece that UMS has co-commissioned with composer Benjamin Bagby and theater director and visual artist Ping Chong.

A Look at the RSC Residency

By far the largest, most expensive, and riskiest component of the UMS theater season is the RSC residency. “It’s the biggest thing we have ever done. Ever,” says Fischer. RSC is presenting all eight Shakespeare history plays in chronological order in a single year, an “extraordinary dramatic marathon,” in the words of the New York Times, that’s rarely been tried on any stage. The company will present four of those productions at the Power Center next March. In addition to paying the staggering cost of transporting a company of fifty-three (thirty actors and a crew of twenty-three) to Ann Arbor for three weeks, UMS is contributing significantly to the cost of producing the series, which will open in its entirety in Stratford, England, move to London, and conclude in abbreviated form in Ann Arbor. No other foreign tour is planned.

The transatlantic partnership that has evolved between the two groups is unique, according to Barbara Grove, RSC’s American representative: “It goes much beyond a tour. This has turned into a prototype.” Under the terms of its agreement, RSC will visit Ann Arbor at least two more times in the next five years and will make UMS its premier university partner in the United States.

The company itself “honestly contends they could not have done this cycle as they’re doing it without the University of Michigan,” Grove says. As a measure of its respect, RSC recently invited Bollinger to serve on its American board of directors.

Bollinger realizes that many in the community find his interest in theater surprising. “One of the great things about being university president,” he admits, “is that people have such low expectations of your cultural interests.”

If UMS is unable to raise its $2.5 million share of support for the RSC project, Bollinger has guaranteed that the university will make up the shortfall. In addition, he has already assembled most of the $20 million it will take to build the Walgreen Drama Center. Michigan alumnus Charles Walgreen Jr. has contributed between $11 and $12 million to the project, and Bollinger will use an undesignated bequest to the university to cover most of the rest.

Arthur Miller Theater

He is especially eager to build the Arthur Miller Theater. While some believe the university is moving too fast on the project—“I believe they should have [first] built an entire theater department, an Arthur Miller School of Theater,” says Rumelhart—Bollinger contends that it’s time the university honored its link to one of the most enduring voices in American, and indeed world, culture. “This is what you hold up to the students—that one of the greatest playwrights of the twentieth century found his talents here,” the president says.

When he first pitched the idea of an Arthur Miller Theater to Miller himself, the playwright sent back a note that now sits, framed, in Bollinger’s office. “The theater is a lovely idea. I’ve resisted similar proposals from others but it seems right from Ann Arbor,” Miller wrote.

The question now is whether Bollinger’s commitment portends a new golden age for theater in Ann Arbor—or whether this is just another bump in the roller coaster.

In Arthur Miller’s heyday, the great playwrights of the age were all seen on Broadway. Production costs and ticket prices for New York and major touring shows weren’t as prohibitive as they are now, and the theater was part and parcel of middle-class life and culture. Certain plays—Death of a Salesman among them—became part of the nation’s collective consciousness.

That happens far less frequently today—“which doesn’t mean the theater is in a bad state,” suggests Enoch Brater, who is organizing this month’s Arthur Miller symposium and will be a key participant in the Musical Society’s theater outreach programs. It does mean, though, that the old rules don’t apply. Theater—especially theater in a digitized, cable-ready twenty-first century—must reinvent itself, as it has countless times in its history, if it is to be anything but a quaintly anachronistic pastime.

Why do people go to the theater, anyhow?

Why do people go to the theater, anyhow? Simply to be entertained? To be sociable? To learn something? Or does live theatrical performance continue to meet some fundamental human need that no other medium can approach?

Obviously, those who have devoted themselves to the art think it does. Broughton believes “the more time we spend in front of these TV monitors, the more we want live entertainment. Theater lets you interact.”

“The more inundated people are with technology that’s been manipulated and studied to appeal to a preconceived notion of what audiences want, the more valuable live performance is,” maintains UMS’s [Director of Programming] Michael Kondziolka. “We program against that culture. And guess what? People are hungry for it. People are coming in record numbers to our programs, which are decidedly non–market driven—if by ‘market driven’ you mean tested and focus-grouped and surveyed and preresearched.”

At Chelsea’s Purple Rose, selling live theater to young audiences, in particular, is “a survival issue,” says artistic director Guy Sanville. “Tomorrow’s audiences are found in today’s classrooms.” What’s more, Sanville contends, theater is “a healing alternative to a chemical high. Arts and music are the drugs of choice for millions of kids.”

At its most basic level, a volunteer theater like the Ann Arbor Civic serves much the same social function as a church—it’s a gathering place for the community. Although he does not want the university’s multimillion-dollar Arthur Miller Theater to serve exclusively as a community theater, Lee Bollinger has said he is “open” to both community and student use of the space. He does not intend to place it under the control of either the theater department or the School of Music, however. Bollinger’s vision is larger than that. He’s convened a universitywide committee to consider plans for the new complex, as well as a trio of informal advisors: Broadway producer Robert Whitehead, Purple Rose founder Jeff Daniels, and Jack O’Brien, a Michigan alumnus who is artistic director of the Old Globe Theater in San Diego.

Bollinger concedes that he’s not yet sure what will go into either the Miller Theater or the Walgreen Drama Center once they’re built. He wants the complex to be a place for the creation of new work. He’ll seek an endowment to fund national and international collaborations with professional companies and a playwright-in-residence program. He’s toying with the idea of finding an artistic director to oversee “major alliances, new-play programs,” and the like. He is “open to thinking about UMS running it.”

He acknowledges that what’s missing from the Ann Arbor theater scene is professional theater of the very highest caliber. But he is admittedly vague about how he would address that deficiency, or whether he even wants to. He’s not sure whether the new Miller Theater should be strictly a presenting house for shows developed elsewhere or should occasionally produce its own plays.

Bollinger hopes to choose an architect by the end of this month. Construction of the new complex is expected to take several years. In the meantime, performing-arts organizations as disparate as UMS, Performance Network, the Ann Arbor Civic Theater, and University Productions, which manages most of the other stage spaces on the U-M campus, are watching developments closely.

A continuing commitment

One thing is clear: although Lee Bollinger’s determination is sufficient to build an Arthur Miller Theater, a continuing commitment will be needed if it is truly to live up to its name.

“Ann Arbor could have as rich a theatrical life as it does music if the University of Michigan, or some other group of subsidizers, will invest for ten years,” Russ Collins believes. “Theater has been strongly supported here in the past, but then debt and ambivalence set in, and it goes away. There needs to be a commitment of a significant period of time.”

Mark Lamos, former artistic director of the Hartford Stage Company in Connecticut and an adjunct professor in the U-M theater department, goes farther: “For a community such as Ann Arbor to support professional theater at the highest level, you need a group of people who believe in it so strongly they will be willing to fund-raise ceaselessly, choose and support artistic and management leaders, and be standard-bearers within the community for the institution. Every great regional theater began as a dream of pillars of the community.”

Such a theater, Lamos continues, also requires “large corporate pockets, large personal ones,” and an audience “that will sustain and support a variety of theatrical productions. An audience for an institution must be developed not through a hit-and-flop mentality but through a newly discovered conviction that the institution itself is more important than any one show—that its artistic mission is worth subscribing to.”

Finding and maintaining such support isn’t easy. Lamos left Hartford Stage in 1997, after seventeen seasons at its helm, because he’d grown tired of the ceaseless struggle for money. “Corporations were merging or downsizing, and the same group of wealthy arts devotees were being pursued by hospitals, universities, the symphony, the ballet, the museum. The community became too small to support my visions of artistic growth and institutional expansion.” Ann Arbor, he points out, is even smaller than Hartford.

It’s unclear, too, how a town the size of Ann Arbor, a four-hour drive from Chicago, the nearest major theatrical center, can attract the country’s finest actors, directors, and designers. Unlike musicians, who can fly in and out of a city in a matter of days or even hours to give a concert, theater artists typically need weeks of ensemble rehearsal to mount a production. Why spend that time in Ann Arbor?

Why spend time in Ann Arbor?

“We have to think about what could happen in Ann Arbor, in regard to theater, that could not happen in New York, Chicago, or London,” says Enoch Brater. “What can we allow theater professionals who are based there to do here that they can’t do there?”

Brater believes the university is the answer. In the absence of significant federal support, he maintains, universities today “are the great patrons of the arts. We can’t rely on Congress anymore. And it’s unrealistic to rely only on private support.”

It’s a vision Lee Bollinger shares—and he’s even writing a book on the subject. Last year Bollinger quietly provided $10,000 in university funds so that, under the auspices of UMS, singer Jessye Norman and choreographer Bill T. Jones could spend a week on campus working, in private, on a project they ultimately premiered in New York as part of the Lincoln Center Great Performances series. According to Ken Fischer, both artists reported afterward that they accomplished more “in one week in Ann Arbor than they could have in three months in New York.”

As Bollinger, Fischer, and their collaborators launch their new theater initiative, they can draw both inspiration and caution from the U-M’s own history. Back in the 1960s, generous university support enabled Ellis Rabb and his APA to develop productions in Ann Arbor that the company then took to New York. At the same time the Professional Theater Program, which brought the APA and other companies to campus in the 1960s, operated with little university control, as UMS does now.

Back in 1961, when university administrators invited Robert Schnitzer and Marcella Cisney to move to Ann Arbor from New York to run the PTP, they offered to build the couple a new theater. The pair turned it down. Writing about that gesture in a 1970 article for Players: The Magazine of the American Theater, journalist Glenn Loney observed, “The American Way is to build a theater in haste and then try to find out how to use it somehow, at leisure. [Schnitzer and Cisney] understood what few other artistic teams have: that you must first find out who your audience is, where it is, what it wants, what it needs—not always the same thing—and what varieties of creativity and service you can hope to present.”

Paradoxically, after Schnitzer and Cisney finally agreed to a new theater, and not long after the university built the Power Center, the couple left town. “It was retirement time, darling,” recalls Schnitzer, who, at age ninety-four, now lives in Connecticut. “I felt I’d paid my dues. It was a strenuous business, that dozen years. We worked like dogs.”

Schnitzer and Cisney were certainly entitled to their retirement, but without their leadership the PTP drifted and soon faded away. What’s to prevent history from repeating itself with the Arthur Miller Theater?

An Audience Ten Years Later

By September UMS had already sold over 1,000 complete RSC cycle tickets, and Fischer and Kondziolka are optimistic that the momentum can be sustained in subsequent seasons. “We think the time is right,” Kondziolka says. “We can help support the university by starting the labor-intensive, difficult work of building an audience, reestablishing a community, so that by the time the Arthur Miller Theater opens its doors there will be an audience ready, willing, and excited to accept this gift.”

That would be a tremendous accomplishment, and an essential prelude to the creation of a successful new theater. But will the Arthur Miller Theater continue to thrive ten or fifteen years down the road, once the novelty of the idea has worn off? Will a 600-seat theater be sufficient to offset the costs of producing or presenting world-class work, especially in a post-Bollinger administration whose focus is likely to be elsewhere? Will community leaders be willing, as Mark Lamos alleges they must, to “do anything on earth—including mortgage their homes” to keep the theater alive? Or was Tyrone Guthrie right when he decided that Ann Arbor couldn’t support the level of theater he had in mind?

At the outset, of course, the ball is in Bollinger’s court. It bodes well that the president himself is passionately excited by the prospect of bringing topflight theater to Ann Arbor. Shortly after Bollinger announced his plans for the building, Russ Collins sent him a note saying he hoped that Bollinger would listen “to his own inspiration and vision on this. It’s going to take that kind of leadership.”

There’s one other piece of advice that Bollinger would be especially wise to heed. It comes from Miller himself, who after all has chosen Ann Arbor as the one city to have a theater bearing his name. When the playwright learned last May that the regents had approved the Arthur Miller Theater, he wrote to Bollinger, “Who would have believed back in 1932–1934 when I was saving $500 to go to Michigan that it would come to this? Now to mount some memorable productions!”

Don’t miss the authors panel on January 28, 2015 at the Ann Arbor District Library, which includes Leslie Stainton as well as U-M faculty Martin Walsh and Leigh Woods. Moderated by UMS Director of Education & Community Engagement Jim Leiha. The panel will spotlight Staging Ground and also provide an updated look at the state of theater in Ann Arbor today.

Resident Update: Painter Carolyn Reed Barritt on superposition

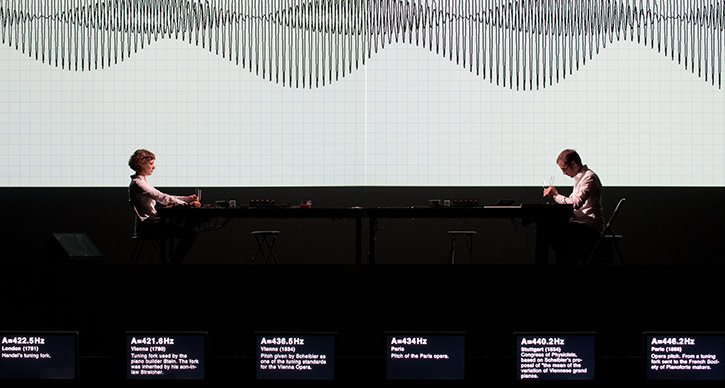

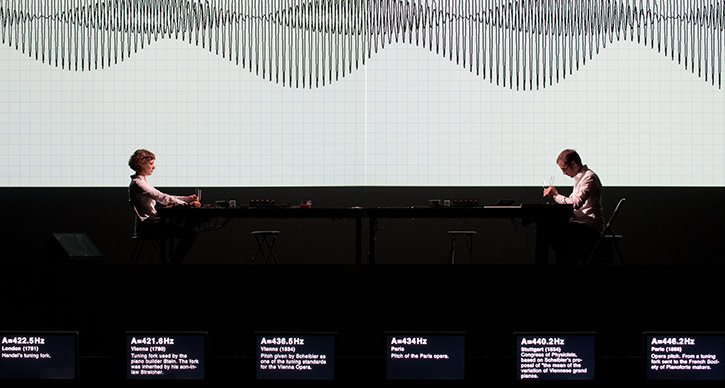

Moment in superposition. Photo by Kazuo Fukunaga.

Painter Carolyn Reed Barritt is a UMS Artist in Residence this season. We’ve asked five artists from across disciplines to take “residence” at our performances and to share the work these performances inspire.

Painter Carolyn Reed Barritt is a UMS Artist in Residence this season. We’ve asked five artists from across disciplines to take “residence” at our performances and to share the work these performances inspire.

Carolyn attended Ryoji Ikeda’s superposition on October 31st, 2014. She shares her thoughts on the performance:

“It beings with darkness. Then strobing white lights, blackness, dust and a million pinpoints of data give way to the machinations of observer/operators who elegantly wend their way towards an understanding of the infinite…..Seeing superposition has made me think a lot more about size and about trying to more elegantly depict the tiny as well as the immense. Maybe more importantly, superposition has made me contemplate obscurity, and I realize now, much more than I did before, that there is no need to continually explain everything. Equally, there’s no need to always comprehend. Sometimes it’s enough to just observe and absorb.”

Read the full post on Carolyn’s blog

Interested in learning more? Read our interview with Carolyn.

Student Spotlight: Could You Repeat That? and Other Stories from Paris

Editor’s Note: Clare Brennan is a junior at the University of Michigan. This past summer she interned for ANRAT, a theater research company in Paris co-founded by Emmanuel Demarcy-Mota, director at Théàtre de la Ville. Their production of Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author comes to UMS October 24th and 25th.

The summer of 2014 consisted mainly of getting lost. As a first-timer to the grand city of Paris, or to any sort of international travel for that matter, I had incessantly practiced the correct way to ask for directions to the bus stop during my entire eight hour flight. Before I could get a “Bonjour” in edgewise, a bored flight attendant directed me towards my destination in perfect English, and I was on my way.

I’d gladly forget my first trek from the airport to the dorms, dragging my two oversized suitcases across town, but after the jetlag wore off, I started to get the hang of things. I became a lover of maps, discovering the metro system as quickly as possible. That knowledge invariably went out the window as soon as summer construction began. Eventually, I started ending up in the same places, and what was once a completely strange conglomerate of streets started feeling a little more like home.

Once settled in, I dove into the incredible wealth of theater surrounding me. With over 150 professional theaters within its city limits, Paris never let quantity deteriorate quality. One of my first shows was Ionesco’s Rhinocéros at Théàtre de la Ville. I had missed the production when it came to UMS last season, and was so excited when fellow UMS intern Flores Komatsu offered up a ticket to join him. We met at the theater and crossed one of the many bridges that connect the vastly different banks of the river to find a small café for dinner. A group of men of various ages played pétanque, the French equivalent of bocci ball, on a dirt patch next to us, a common pastime on summer evenings. Obviously American, we prattled away, catching up on upcoming projects, book recommendations, and travel plans. Eventually, the couple from Colorado sitting next to us struck up a conversation, and after twenty minutes we had learned the story of their ex-pat daughter and swapped recipes for favorite dishes we’ve discovered. Caught up in conversation, we barely realized we were running dangerously close to curtain time. We sprinted back to the theater and found our seats with just enough time to absorb the atmosphere.

*

I love theaters. Between their velvet curtains and cushioned seats, both actor and audience member gain some security to suspend their disbelief for a while and hear a story. I appreciate that sense of trust that seems built into the walls, and I always try and find it again before every show I see.

At Théàtre de la Ville, the most striking quality I found was its size, housing around 1,500. Our Monday evening show was sold out, and as I looked around, I noticed that most of those in attendance were around my age. In my exploration of the arts at home, I’ve often found truly invested younger patrons more difficult to find. There, young people come to shows, stay for talkbacks, and attend season premieres; Théàtre de la Ville’s season announcement, for instance, packed the house just as tightly as their best-known runs.

Photo: Le Palais de Pape, where “I Am” played during the Avignon Theater Festival in July. Photo by Clare Brennan

The house lights dimmed, and I experienced again what would quickly become one of my favorite culture moments abroad. Before an actor ever sets foot on stage, a score of audience members will audibly shush one another. It will be hard to forget my first experience of this sort, as the majority of hisses were directed at me. Foreign air and a lack of sleep had left me sick for a couple weeks, and, apparently, I thought that the start of the Moroccan acrobatic performance Azimut at Théàtre du Rond Point would be a lovely time for a coughing fit; the surrounding patrons did not. I quickly picked up this less-than-subtle social cue, and by the end of my two months, I was joining in as passive-aggressively as possible. Strong reactions like this were never out of place. At the Avignon Theater Festival, a production of Lemi Ponifasio’s I Am, a World War II homage in dance, produced critical laughter, side comments, even a small exodus after a particularly difficult movement. However, with this piece included, I also never saw a performance without at least five minutes of applause at the close.

*

Seeing theater in a foreign language took a bit of adjustment. Rhinocéros opens with a beautiful monologue. I couldn’t tell you what the first few lines mean now, as I was still looking for surtitles within the first few moments before I remembered where I was. I did have opportunities to try reading French surtitles during a Dutch production of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead and a Japanese kabuki style of the Mahabharata. Reading and translating French while listening to another language with which I had no experience left my American brain a little withered, but it did help me to abandon any pretenses I had when I arrived and dedicate a couple of hours to a completely new experience. Or four and a half hours, in the case of the Dutch Fountainhead. (I have to admit, I dozed off for about twenty minutes of that. I read the book in high school, so that counts, right?)

That night, Flores and I left the theater and lingered on the rainy sidewalk with a crowd of theatergoers doing the same. We all shared our thoughts, compared interpretations, raved over actors, and tried to weave our way through the denser moments. We said our goodbyes for the night, and as I turned to leave, I realized that I was pretty disoriented. I was lost in Paris again, but what else was new. Theater abroad left me dizzy and buzzing, not quite sure of where I stood but happy that I was there. I was used to the feeling by now, and there could be worse places to get turned around. Paris is a city for wandering, anyway.

Artist Interview: Ryoji Ikeda, creator of superposition

Photo: Moment in superposition. Photo by Kazuo Fukunaga.

superposition is a performance created by visual and sound artist Ryoji Ikeda. Inspired by the mathematical notions of quantum mechanics, Ikeda employs a spectacular combination of synchronized video screens, real-time content feeds, digital sound sculptures, and for the first time in Ikeda’s work, human performers.

The work will be premiered at the MET in New York City immediately before it arrives in Ann Arbor on October 31 and November 1.The interview excerpted below is between Ryoji Ikeda and Peter Weibel, and was recorded at ZKM Karlsruhe on July 31, 2012 by Manuel Weber and transcribed by Wolfgang Knapp.

Peter Weibel: First, thank you for the time and opportunity to speak about your work. My first question would be about title: superposition. Are you referring to the quantum mechanical idea or are you referring to the cinema, where you work with superpositions. What is the idea behind the title?

Ryoji Ikeda: I have never specified anything. How did you feel when you heard the word “superposition”? I am very curious about people’s can impressions when they hear “superposition.”

PW: Well, I would think of the wave function of Schrödinger, from quantum mechanics. Then I would think of the super-imposing of image on image, and then I would think of the observer who has a position superior to anything else.

RI: Because you are a very intellectual person. When you hear the word superposition, you are inspired. But, for example, my mother just thinks, “Super! Position!” The word has a very wide spectrum of meanings, and I think that’s good. People can get many meanings. And of course, I am obsessed by that quantum mechanical meaning. And also, the other superposition principle, the fundamental principle of physics. For example, the harmonics that superpose and that make our voice and sound.

superposition performance trailer:

PW: So you are also thinking of musical notations? Of the superimposition of frequencies?

RI: Yes, exactly. But the core topic for me is the quantum mechanical meaning, the fundamental characteristic of quantum physics.

PW: When did you become interested in the quantum nature of reality? And why?

RI: I read some books when I was a student. Of course, it was really difficult and pretty counter-intuitive. But it stunned me to discover quantum mechanics. After that, I became an artist, but it was absolutely impossible to describe quantum mechanics for my art. So, I just make a piece of art. It’s a performing art piece, which never explains quantum mechanics. It is rather inspired by quantum mechanics. Some of the expressions are scientifically correct. I use lots of data sets from NASA and so on, but the construction, the composition is very intuitive because I am an artist. So, it’s hybrid.

PW: I see. I can imagine that when you have to make a decision between the classical world view — that means causality and mechanics — and quantum mechanics, I think that, as an artist, the idea of uncertainty or of many different possible worlds is more attractive. I think all these possible worlds give us — as artists — more freedom.

The people who help you working on the superposition performance – your assistants; are they programmers? Musicians? What is their profession?

RI: They are basically programmers. And architects and all kinds of artists. They are very young, in their twenties. They can program almost in every language. Super.

PW: I have a question for you as an artist. How do you solve the following problem? Morton Feldman, the wonderful American composer, said that music is structure. Normally it is time-based structure. But Feldman disliked most kind of music because it is a slave of time. Rhythm and beat – these things control the music. Time tells music what to do. But Feldman wanted to destroy this control. He wanted music that was not slave to time. How do you solve this problem? Can we create a music that is superior, music that destroys our structure of time?

RI: I really like most of Feldman’s music and his philosophy, but I can’t really follow him. And after John Cage and after that generation, you know, and the generation of computer and programming, my direction is super-precise, it is the direction on “control.”

PW: So, no chance experiments like Cage. Control instead of chance.

RI: I try to control randomness. This is a big counterpoint, the encounter of randomness and control. The contrast is more interesting. If you really control a millisecond, there are other possibilities, even if they are microscopic. You can’t perceive the change directly, but if you pay very close attention, the entire composition changes. So, I try to add randomness, and I like to see the counterpoint, the counterbalance.

PW: Schönberg in his book Style and Harmony stated that the composer’s challenge is to move from one note to the next. You don’t work with notes but with waves, continuous sine waves. A note is a discrete model. As an acoustic artist, how do you see this problem?

RI: Of course, I use sine waves, pure waves, but if you reduce the waveform to its function, this point is very, very tiny and is called the impulse. It is so short that when you listen to such a sample you don’t hear it. The point is what makes the acoustics. Sine waves are continuous, they have no direction. They never contribute to acoustics.

It’s the opposite of white noise, which is random. That’s a different thing, but I use lots of impulse, as you will hear. I’d never use one hundred speakers like [the composer] Stockhausen does. No. Mono! At the center of a church or some very large space, maybe just an impulse on a single mono speaker. That would make you feel the very acoustics spatially through some rich reverb created by that very short impulse.

PW: I see. The acoustics of a wave is a kind of point you…

RI: …you slice.

PW: Exactly.

RI: Any point.

PW: Brilliant idea. So I see that you are now investigating not only a new organisation of sounds but a new series of harmonies on a technical and mathematical basis.

RI: Yes. That is my basic research. This is not really the work of an artist but basic research for basic knowledge to find my language. To develop my alphabet and the grammar is my structure, my music. And I don’t want to use the normal alphabet.

Interested in learning more? See Ryoji Ikeda in Ann Arbor as part of the Penny Stamps Lecture Series and also the Saturday Morning Physics Series. Details on ums.org.

Artist Interview: Traveling with Théâtre de la Ville

Editor’s note: This summer, UMS launched a new 21st Century Artist Internships program. Four students interned for a minimum of five weeks with a dance, theater, or music ensemble part of our 2014-2015 season. Héctor Flores Komatsu is one of these students. He spent five weeks with Théâtre de la Ville in Paris, France.

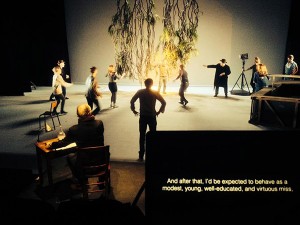

Théâtre de la Ville performs Six Characters in Search of An Author at the Power Center in Ann Arbor on October 24-25, 2014. Photo by JL Fernandez.

Scene

13:30, May 23, 2014, Paris, France. En route to final dress rehearsals of Six Characters in Search of an Author at Le Forum Blanc Mesnil, a banlieu (suburb) located at the northern outskirts of the city proper. Cast and production members sit throughout the van shuttle between Théâtre de la Ville and our current rehearsal space.

Les mecs (the dudes) hang out in the back, and one of their phones alternates between the American and French pop hits of the moment. Some nap, some read, some eat their lunch. They converse in the relaxed, soft, yet gutturally vibrant and “chic” French that had initially been both inviting and intimidating to my Mexican-American mélange of an accent.

Actress Sarah Karbasnikoff’s sweet, edgy, yet motherly voice, proper for her character, rises in joyous laughter, while actress Valerie Dashwood’s dark, yet subdued, cedar timbre seduces the air with chuckles, not unlike those heard from her character, the Step-Daughter. The laughter is inviting, I sit across them, speaking in “tu,” not “vous,” as they had requested.

We chat for the readers in Ann Arbor, of which Sarah has fond memories with Rhinos stampeding through the fallen autumn foliage. (Théâtre de la Ville last visited Ann Arbor to perform Ionesco’s Rhinocéros in 2012.)

Héctor Flores Komatsu: You are a very interesting mother-daughter stage pair! Could you talk a bit about your characters’ relationship in the show?

Sarah Karbasnikoff: Well, I play the Mother, who… Let’s just say she suddenly arrives at the theater with her first husband and all of her children.

HFK: Hmm…

Sarah: Ha! That’s what you need to know, I don’t think I should say more!

[Laughter]

Valerie Dashwood: As for me, I play the “Step-Daughter.” She is such because her mother…

Sarah: That’s me…

Valerie: Was initially married to the character of the Father, with whom she had…

Sarah: A boy.

Valerie: Yes, a boy… Just one boy.

Sarah: Voila!

Valerie: Afterwards, she “had” a second man, my true father, with whom she had three children of which I play the eldest, the Daughter.

HFK: What would you then say is the fundamental need, desire, of the mother, of the Step-Daughter, of the family as a whole? What is it? Is it love? Is it to unite the entire family? Is there a common desire as a family?

Sarah: Well, that will certainly differ for each character.

Valerie: For the Step-Daughter there’s no need or desire to be part the family. One of the first things she says is that she “will take off – fly away!” because she doesn’t want to be part of it.

Deep inside, she detests her Step-father, and she also hates his first, legitimate, son. She speaks a lot about legitimacy, because perhaps she doesn’t feel entirely legitimate. She doesn’t have legitimacy even within society, given that she’s had to prostitute herself to support her mother and siblings. That’s her point of view.

Her desire is, more than anything, is to self-destruct, through which she can emancipate herself from her family, become and adult.

HFK: She fights for her freedom!

Valerie: She fights for her freedom!

HFK: For the mother it seems to be quite the opposite.

Sarah: Each day I discover her a little more. At this moment I have the impression that, yes, she seeks to see her son again, that is certain, because she wasn’t there for him, and so there’s some degree of guilt. Her two youngest children die, and eldest daughter wishes to escape from her. So yes, her greatest desire is to bring everyone together but, alas, that’s impossible. Her life is her children, all of whom escape from her, leave her.

During rehearsal with Théâtre de la Ville. Photo by Héctor Flores Komatsu.

HFK: How has the process been for you, as a new actress in this restaging, stepping into a role originated by someone else?

Sarah: Well, first one must do what’s already been done and understand what already exists. I’ve been stepping into the shoes of the original actress.

And now, with each run, I begin to understand the reason behind her movements, the psychological motivations. At first they were mere just movements, crossing from one place to another, and I simply memorized them; it was very concrete, very technical work. And then, from that point, I began to create the character.

HFK: For you Valerie, having played this role in the original production twelve years ago, what has it been like this time? What has been unearthed once more? What has been newly discovered?

Valerie: What’s been really interesting for me, since it’s been twelve years since I played this role in the original production, is that upon returning to this play, I could not perfectly recall many specifics, but I still had a global feeling of the character, the violence, the pain, and of the will – that’s what it is! The will of the character, is what I remembered well.

However, I could barely remember the text – except for the song! Bizarrely, that had completely stayed with me; I remembered the song… but not my lines!

But then when we read out the play all together at Théâtre de la Ville, with Hugues [Quester, who plays the Father] and Alain [Libolt, who plays the Director], hearing their voices and feeling their energies through the text, the memory came back to me. By reading with them, I was surprised to feel the same emotions from years ago resurface, as if something which long laid dormant suddenly awoke, opening itself. Voila!

After that, relearning the text was very easy.

HFK: What is different today, than how it was twelve years ago?

Valerie: The biggest difference is that twelve years ago I didn’t have children, and now I’ve had two. So my maternal instinct, the one my character has for her little sister, feels very different. Motherhood has hit me hard, and it affects how I act, even in the way I look at the little girl. Sans resorting to any psychological tricks, I instinctively see my daughter in the little girl. I have a child now… And that fact greatly affects how I act, knowing that this little girl, in the play, will die.

I don’t think I could ever do this in the same way as I did twelve years go.

Also, having worked so much in just the past ten years, I feel much more physically available in my own body, much more reserved. At the time, the nudity had originally been somewhat difficult for me, but much less so nowadays. That scene, which I came to fear, I now approach with serenity, even when it’s hard to play.

HFK: And now for my last question for you. I’ve noticed that there’s a lot of love and care behind the scenes among the cast. And for you two, who play Mother and Daughter on stage but are much closer in friendship and in age off-stage, how does that affect your stage relationship?

Valerie: All I can say is… Just like in our previous play, I played the mother to Sandra [another Théâtre de la Ville actress who also plays one of the “actresses” in Six Characters]. I never feel the need to ask myself whether this is or isn’t “coherent,” even if we are only twelve years apart. In theatre, we have what we call, at least in French, a “convention” to suspend disbelief. So right now, Sarah may be playing my mother, and we understand each other really well, which is good because playing this relationship requires great emotional investment. We can support that off-stage. Our closeness strengthens the bond vital to plunging into the work together.

Sarah: For me it’s very similar. During the show I don’t think at all about the age difference. To feel Valerie as she plays her character, I do nothing more than to say “she’s my daughter.” That’s it, I don’t see the age at all. There’s also an understanding of our respective pains, because we know each other personally. That really gets me, it truly does. She does, her pain. She might not truly be her character, but we form an affinity, a bond.

We streamline into casual conversation, and soon enough arrive at the theater. An hour into the rehearsal, as everybody gets into costume and warms into their roles Valerie receives a phone call. Her youngest child isn’t feeling well. She ponders the symptoms, trying to figure the right remedy. There’s the natural concern of the working actress-mother in the midst of rehearsals. She seeks her stage-mother Sarah, a veteran mother in various senses, for reassurance. That’ll do it,” Sarah says. For a moment, the parallel lines of reality and fiction intersect, not unlike in the play, as the two women connect through maternity.

Interested in more? Look for Flores’s behind-the-scenes photo-essay covering his time with the company.

Data as Playful: Sonification Specialist on superposition

Scene from Ryoji Ikeda’s superposition, at Power Center October 31-November 1. Photo by Kazuo Fukunaga.

Robert Alexander is a sonification specialist working with the Solar and Heliospheric Research Group at the University of Michigan, where he is pursuing a PhD in Design Science. He is also collaborating with scientists at NASA Goddard, and using sonification to investigate the sun and the solar winds. We chatted with Robert about his fascinating work last season.

As it happens, Robert is also a big fan of the visual and sound artist Ryoji Ikeda, whose work superposition will be premiered at the MET in New York City immediately before it arrives in Ann Arbor on October 31 and November 1.

Robert chatted with us about what’s special in Ryoji Ikeda’s work, beautiful and playful data, and lion roars in the universe.

UMS: What inspires you about Ryoji Ikeda’s work? What in Ryoji Ikeda’s work influences the way you think about your own work with data sonification?

Robert: Ryoji’s work directly addresses the aesthetics of data. Within Ryoji’s work, we’re not only exploring data as beautiful but also data as playful. Data as immersive. Data as illusory.

He inspires me to think about how I represent scientific data sets. His work conjures the scientific and the precise and plays with these notions of accuracy, and he is very much playing quite often. As a data sonification specialist, I’m aware that I can also play with that balance between scientific representation and appealing directly to the notion of the “wow,” the sublime.

That’s what science can be. It can remind us of the beauty of this universe that we live in, the sublime experience of being alive. And sometimes the scientific representations can potentially sterilize that which may otherwise be enigmatic.

Performance trailer for superposition by Ryoji Ikeda:

UMS: You’ve seen Ryoji Ikeda perform multiple times. Can you tell us about one of those experiences?

Robert Alexander: One initial experience was at the International Conference of Auditory Display in Washington D.C. I had the chance to take in his work up close. He invited everyone up to sit on the stage, and I was sitting a few feet from the projection screen. His work lends itself so well to massive scale. It’s meant to completely absorbed, it’s meant to be immersive.

During this experience I was also captivated by his masterful ability to direct attention. As a composer or film producer, you’re often holding the audience’s attention almost like a tiny baby bird in your hand. You’re cradling the audience’s attention, and if you jar them, then that’s going to pull them out of the experience, but if you don’t provide enough stimulus, they get bored.

I was amazed at Ryoji’s ability to craft an experience such that I never felt pulled out of it. I was continuously pulled deeper into the work, I was continuously searching for deeper levels of meaning.

Spektra by Ryoji Ikeda:

UMS: How would you describe this work to someone who’s not familiar with it, someone who’s never had an experience like this?

Robert: I would probably pull out my phone and put the flash on the strobe function, point it directly at their face, and begin beeping at them [Laughs] I would say that’s about as close as I could get.

One perspective or take that might help someone new to the work is light. So, let’s say we go camping, and when we get there, we turn on our headlamp in the tent. Now we have minimal control of our environment, and yet we still feel that we have an element of modernity, so long as we are able to bring light to the space, even in its most rudimentary form.

When you think about representations of “the future,” be it eastern or western, many of them are ripe with dazzling displays of light, holographic representations.

When you think about Ryoji Ikeda’s work, let your eyes glaze for a moment, and what you’re witnessing is essentially a dance of light. He’s playing with light sculpture quite often, like in his work Spectra in London. He is both invoking this vision of the future, and yet working with just a single, minimal column of light. To truly appreciate this work you need to experience it, to stand beneath the pillar of light that he shot into the sky in this case.

And so, it’s fascinating how he goes about playing with light, but also sound. The auditory tapestry that he weaves, it vibrates with these simple minimal waveforms. We’re not used to the high frequency sounds in his work without those types of sounds signifying something important. We’re used to these beeps signifying a tele-type or a print out or a digital display, and the precision of these sounds coupled with the visual conjures this deeply synesthetic experience.

It’s absolutely hypnotic. I think that’s the way it’s meant to be experienced, as a complete sensory immersion.

UMS: We’re excited to be immersed! We also want to know about your work. What projects are you working on now? Do you have any updates for us since we last chatted last season?

Robert: I am still working very closely with a number of scientists at the NASA Goddard Spaceflight Center. Just recently, we published a case study titled “The Bird’s Ear View of Space Physics.” “The bird ear’s view” is a notion that we’ve used to describe what listening to data can provide. For example, when you listen to a data stream that’s been collected via satellite, you can hear minute fluctuations in something like the solar magnetic field. When you convert that to sound, given the rate of sound file playback, 44,100 data samples per second, we can hear the evolution of this data set across multiple days of real-time recording in just several second of listening, which is rather incredible.

In this case study, we worked closely with a single research scientist. First we introduced this scientist to these techniques of listening to data, and then we tracked how these techniques were integrated into his workflow, the types of observations that were made through listening, and how those observations led to additional formal investigations through visual analysis and through statistical analysis. And so this paper is great in that it covers the complete process for someone who is first introduced to this technique and then ultimately uses it to extract new knowledge from data sets.

Also, there are now many terms in the space research sciences, particularly helio-physics, terms such as “chorus,” “hiss,” “tweets,” “lion roars,” terms for physical phenomena, that have roots within auditory observations. For example, “whistlers” which are essentially results of lightning strikes that can be heard in very low frequency on radio waves, can be heard as this descending whistling sound, so the term “whistler” is now the default nomenclature for this phenomenon. It originally came about through just listening to the data, it’s an acoustic description. And then there are “lion roars.” Again, researchers were listening to a data set and they heard kind of a low “Grr” sound, like a low roar of a lion an the Serengeti [laughs], and that term has now stuck. It’s been really fascinating to work with research scientists, to play them some of their data sets and actually see the epiphany moment as their gears turn, and they say, “Aha!, that’s why we call it a ‘lion roar.’” [Laughs]

UMS: This all must be incredibly rewarding for you, to see your work receive this kind of support?

Robert: It’s been unbelievably rewarding to work alongside these research scientists and some of the brightest minds in the world and to be able to help provide a fresh perspective to these data sets, and also to provide them with the knowledge and infrastructure to apply these technique on their own. And that’s ultimately the goal, to enable the scientific community at large to adopt the practice of listening. It has been and continues to be an incredible experience.

Interested in learning more? See Ryoji Ikeda in Ann Arbor as part of the Penny Stamps Lecture Series and also the Saturday Morning Physics Series. Details on ums.org.

Who Are We?

Théâtre de la Ville performs Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author at the Power Center in Ann Arbor on Oct 24-25, 2014. Photo by JL Fernandez.

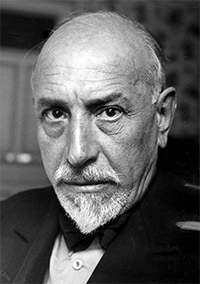

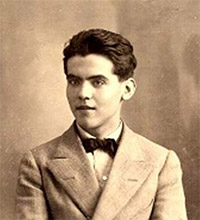

While I was working on a biography of poet, playwright, and theatre director Federico García Lorca many years ago, I was startled to discover that Lorca had planned to meet up with the dramatist Luigi Pirandello in Italy in 1935. The two intended to collaborate—but Lorca cancelled the trip after Mussolini invaded Abyssinia (it was one of the rare overtly political gestures of Lorca’s life), and the two men never met.

I’ve often wondered what would have happened if they had. For both playwrights shared, among other things, a fascination with the nature of theater. Lorca probed the topic throughout his life, in plays that contain plays and rehearsals within plays, plays whose cast lists include directors and actors and playwrights (including Lorca himself). He introduced all manner of theatrical claptrap into these works—puppets, masks, screens (behind which identities abruptly change), miniature stages, outlandish costumes and props.

Pirandello was similarly obsessed. You see it big time in Six Characters in Search of an Author, a play that, if done well, should produce something like imaginative whiplash in the audience. (I’ve only seen the work produced once, in a student production at NYU, with way too much scenery-chewing. But having seen Théâtre de la Ville’s exquisitely nuanced production of Ionesco’s Rhinoceros two years ago in Ann Arbor, my hopes are high.)

What’s real? Who’s acting?

On left, Luigi Pirandello, and on right, Federico García Lorca.

What’s real? Who’s acting? Are the events and emotions we see onstage reality? Is what we experience and witness in “real life” acting? Can you trust what you see on a stage? In a conversation with your spouse or best friend or boss?

Aren’t these the questions that lie beneath the pleasures we associate with theater? (With film too, but I don’t think the experience is ever quite as acute on a screen.)

The setup for Pirandello’s exploration of theatrical artifice is straightforward: six purportedly fictional characters barge into a mostly empty theater to impose their story on a director and group of actors who are trying to rehearse a play. Actors become audience. Characters become actors. The layers multiply and confusions mount.

In line after line, we’re asked to consider the contradictions at the heart of play-making.

DIRECTOR: Then the theater is full of madmen, is that what you’re saying?

FATHER: Making what isn’t true seem true … for fun … Isn’t that your purpose, bringing imaginary characters to life?

Elsewhere the Father—one of Pirandello’s “six characters”—cries out that his story isn’t literature, it’s “life! Passion!” To which the Director responds: “That may be, but it won’t play.”

“What’s a stage?” a character asks toward the end of the play, and answers her own question. “It’s a place where people pretend to be very serious.”

The Empty Space

Exchanges like this abound—and make you question the theatrical enterprise and its conventions. Do we really need all the devices we’ve come to associate with the theater? The curtain and spotlights and scripts and applause? Peter Brook famously said (in his indispensable 1968 book The Empty Space) that in order for an act of theater to take place, all you need is for one person to walk across an empty space while another watches.

Brook published his book some 40 years after Pirandello wrote Six Characters, which opens on a stage whose atmosphere, Pirandello instructs, “is that of an empty theater in which no play is being performed.”

The Italian Pirandello grew up steeped in the venerable stuff of theater—the comic and tragic masks of the ancient Greek and Roman stage, the stock characters of thecommedia dell’arte. He understood (as did Lorca and that greatest of playwrights, Shakespeare) that identity is at the core of acting. As one of Pirandello’s six “characters” points out, “We all try to appear at our best, but we all know the unconfessable things that lie within the secrecy of our own hearts. We are not what we seem—even to ourselves.”

Don’t you change your personality according to the situation and your audience?

In another book I find indispensable, The Actor’s Freedom: Toward a Theory of Drama (1975), critic Michael Goldman probes precisely these questions. Identification is the “covert theme of drama,” Goldman writes. This isn’t simply a matter of actors identifying with roles but of “the making or doing of identity.” You watch an actor, onstage or on screen, and wonder where her private life stops and the public, performed one begins, what parts of herself we see revealed in her role.

“It should not be surprising, then,” says Goldman, “that the process of identification in this sense—of establishing a self that in some way transcends the normal confusions of self—is remarkably current as a theme in plays of all types from all periods, from Oedipus to Earnest to Cloud Nine.” Add Six Characters to that list.