UMS Playlist: Social Change and African Popular Music

This post is a part of a series of playlists curated by UMS staff, artists, and community. Check out more music here.

Oliver Mtukudzi. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Zimbabwe’s Afropop legend Oliver Mtukudzi performs in Ann Arbor on April 17, 2015.

“Tuku” has created 61 solo albums to date, many of which focus on political and social themes. His band The Black Spirits got its start performing songs protesting the white colonial rule of Zimbabwe in the 1960s and 70s.

Throughout his career, Tuku has refrained from direct political criticism, instead using metaphor to communicate his ideas: “The beauty of the Shona language is that it is endowed with all those rich idioms and metaphor…and the beauty of art is that you can use the power of language to craft particular meaning without necessarily giving it away. So, I used the beauty of Shona to communicate in my own way and people got the message.”

Themes of social change are common in popular African music. In this listening guide, explore some of the history of this connection.

1. Nelson Mandela commissioned the group “Sipho Hotstix Mabuse” to write a campaign theme song for his bid to be South Africa’s first democratically elected president in 1994. Simply titled “Nelson Mandela,” the song speaks frankly about the Mandela’s hopes to promote unity in the country.

2. Angelique Kidjo (who last performed in Ann Arbor in 2013) blends musical traditions from her native Benin with Western popular music, singing in English as well as her childhood languages of Fon and Yoruba. Many of her songs include themes of peace, tolerance, and liberation. In “Kulumbu,” Kidjo speaks about the nececsity for women to participate in conflict resolution after suffering disproportionately during war.

3. The title of Bassekou Kouyate’s song “Jama Ko” translates to “the gathering,” and urges for peace and reconciliation in Mali. Bassekou Kouyate last performed in Ann Arbor as part of our 2013-2014 season.

4. Tuku’s song “Wasakara” describes the corruption and violence of the government of Zimbabwean president Robert Mugabe. He sings, “Admit it, you are wrinkled/You are worn out.”

5. Thomas Mampfuno also criticizes the government in “Mamvemve,” with the lyrics “the country you used to cry for is now in tatters.” Zimbabwe’s political environment is so restrictive that Mampfuno has not visited the country since 2004.

6. In “Ndakuvara,” Mugabe is represented by an ox too stubborn to learn from its elders. Through metaphor, Tuku writes protest as subtext subtle enough to allow him to remain in Zimbabwe.

What did you think about this playlist? What songs would you add?

A Taste of Tropicália

Photo: Brazilian star Gilberto Gil performs at Hill Auditorium on April 4, 2015 at Hill Auditorium. Photo by Jorge Bispo.

Photo: Brazilian star Gilberto Gil performs at Hill Auditorium on April 4, 2015 at Hill Auditorium. Photo by Jorge Bispo.

The Brazilian Tropicália movement in the late 1960s is perhaps one of the greatest examples of music’s ability to be a powerful purveyor of change. The music created during this short time was a combination of Brazilian and international popular music; there were “mash-ups” of influences as varied as the Beatles or Jimi Hendrix and rhythmic Brazilian dance music like bossa novas or sambas. Many Brazilians saw this new music genre as “an adulteration of Brazil’s musical birthright by an American aesthetic.”

During this experimental, avant-garde period of musical expression, a military dictatorship loomed, ever present. Within a year, the leaders of the movement were imprisoned and then exiled, but they were not silenced, and others stayed and continued to perform their music. Over the course of the movement, the Tropicalistas began to inspire a generation with their exhilarating music as well as their indestructible spirit.

To offer a small taste of the power of the music created during this brief time, we have chosen some songs performed by four of the main players in the movement: Gilberto Gil, Caetano Veloso, Gal Costa, and Maria Bethania. Take a listen below!

Gilberto Gil is one of the most talented and prolific of the singer-songwriters to come from Tropicália. He has broached a wide variety of issues in his work; for example, he speaks often about social inequality and the conflict between science and religion. The song “Domingo no Parque” is one of Gil’s most popular songs. It was written in 1968 for his Gilberto Gil (Frevo Rasgado) album. The album is typical of Tropicália in its blending of traditional Brazilian styles with American rock and roll, while also mixing Rogério Duprat’s orchestral arrangements with Os Mutantes (mentioned below). Rolling Stone voted the track “Domingo no Parque” as one of Brazil’s greatest songs. Here it is!

Gilberto Gil performed at Hill Auditorium in 2012 and will return for another performance on April 4, 2015.

Caetano Veloso is another well-known singer and composer from that time period. In his 1968 debut album Caetano Veloso, he included a song titled “Tropicália.” The song got the name because of similarities between its content and that of Hélio Oiticica’s installation art piece. In fact, the song was entirely written before that name was assigned to it, and that name was never even meant to be a permanent title for the piece. The name caught on though, and soon it became a label for the entire movement of Tropicália.

Gal Costa is a female vocalist from the time period, and she worked quite frequently with the the other artists listed here. Her eponymous solo debut album in 1969 was hailed a Tropicália classic and was highly influenced by American psychedelic music. “Baby” was written by Caetano Veloso and performed by Costa. She speaks about how English should be learned in Brazil and mentions several pop references as well. A common trait of Tropicália music is that it mixes popular and traditional culture.

Rita Lee, Arnaldo Baptista and Sérgio Dias formed Os Mutantes, a popular Brazilian psychedelic rock band that became linked to Tropicália. The band reunited with different members in 2006, and has been touring and recording new material. Os Mutantes, the album released in 1968, includes compositions by both Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil. Gal Costa has also sung on several of their albums.

Even a brief overview of Tropicália shows that this late 1960s brief period of innovation and excitement has remained popular and produced a huge, lasting change in the Brazilian music scene. Teamwork and collaboration were key during this movement, and it was a time to point out flaws in Brazilian culture while working to create a positive change. The movement also provided inspiration to other artists around the world, such as David Byrne and Paul Simon, and many songs have been written in reaction to Tropicália. Artists active during Tropicália have continued to create music even when they have moved away from the original purposes of the movement, and they and their music have become an ever present part of Brazilian culture.

UMS is excited to bring a taste of one of Tropicália’s iconic members to Ann Arbor on April 4, 2015 at 8 pm in Hill Auditorium. We hope that you will come join us in hearing the astoundingly charismatic and influential music of Gilberto Gil.

Sources:

- Cahill, G. (2011, Jun). Tropicalia thunder. Pacific Sun. Retrieved April 8, 2014, from http://search.proquest.com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/docview/874154508?accountid=14667

- Os Mutantes. (n.d.). NPR. Retrieved April 8, 2014, from http://www.npr.org/artists/17080024/os-mutantes

- The Best Tropicalia Albums: Sounds and Colours. (n.d.).The Best Tropicalia Albums: Sounds and Colours. Retrieved April 8, 2014, from http://www.soundsandcolours.com/guides/the-best-tropicalia-albums/

- Tropicalia. (n.d.). PBS. Retrieved April 7, 2014, from http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/cultureshock/flashpoints/music/tropicalia.html

A Closer Look at Qawwali: Interview with Farina Mir

Photo: Asif Ali Khan Qawaali Music of Pakistan performs.

On Friday, March 21, 2014 at 8 pm, UMS presents Asif Ali Khan Qawwali Music of Pakistan in Rackham Auditorium. A protege of the late, legendary Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan (1948-97), Asif Ali Khan performs the beautiful tradition of qawwali music of Pakistan and India. Whether you’re an adherent of the Sufi faith or not, the aesthetic experience of qawwali music is unique, inspiring, and inclusive.

To hear more, we talked with Farina Mir, the Associate Professor of History and Director of the Center for South Asian Studies at the University of Michigan. She is also the author of The Social Space of Language: Vernacular Culture in British Colonial Punjab (University of California, 2010), and co-editor of Punjab Reconsidered: History, Culture, and Practice (Oxford University Press, 2012).

Farina was fortunate enough to hear Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan perform, and the experience changed the professional focus of her life.

UMS: Tell us about your experience seeing Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan.

Farina Mir: I heard Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan at a charity dinner in New York City when I was only a junior in college. At the time, I hadn’t heard of the artist and was totally unfamiliar with the art of qawwali. I had only just started studying South Asian history; though, it quickly became a passion. I was particularly drawn to the history of the partition of India in 1947, which had led to the creation of Pakistan. This was a cataclysmic event, in which at least 17 million people migrated across newly created international borders (the largest peace time-migration of the twentieth century) and as many as one million people died in mass civil violence between members of different religious communities. I was particularly troubled by the violence of partition. The history I had learned—the standard history of the event at the time—found the roots of partition in “communalism,” antagonism along religious lines. It was a history that led one to think of Hindus and Sikhs, on the one hand, and Muslims on the other, as mutually antagonistic communities. What I saw at the charity concert undermined for me the certitude of this historical argument.

Many Voices

The audience for this concert wasn’t large; a relatively small hotel ballroom with people sitting at tables of 8 or 10, so maybe 200-300 people. Most of those in attendance were South Asian Muslims, but there was at least one table of Sikhs and Hindus. They stood out from the rest of the crowd because some of the men wore turbans and had unshorn beards. What stood out less than their presence—I knew from my own experience of growing up in the South Asian diaspora that members of all religious communities from the subcontinent intermingle socially—was their repeated requests for Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan to sing the compositions of particular Sufi poets. Qawwali as a genre is Sufi mystical poetry set to music. How were non-Muslims so familiar with Muslim Sufi poets, I wondered? And not only were they familiar with the poets’ names, but with particular compositions. They were making requests by reciting lines of Punjabi verse. And when Nusrat acknowledged their requests, I was struck by the looks of rapture of everyone around me, Hindu, Muslim, and Sikh alike.

An Enlightening Discovery

I, too, was taken in by the performance, by the pure pleasure of it—Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and the qawwali form are nothing if not immensely powerful and emotive. But I was also taken in by the context of the performance. It produced a dissonance for me. I was struck by how the history books I was reading all emphasized Hindu, Sikh, and Muslim difference, yet what I saw that evening was a shared experience that defied the expectations produced by those history books. I began to wonder if there were historical antecedents to what I experienced that night. This led me to consider the historical role of the Punjabi language and its literary texts, including those of Sufi poets I heard at that performance, as the site for shared experiences among Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs. What was hinted at in my experience that evening—the meaning, power, and pleasure of texts shared by members of different religious communities—led me to pursue a PhD in South Asian history, and today I teach in the history department at U-M. My book, The Social Space of Language: Vernacular Culture in British Colonial Punjab, provides one set of answers to the questions that emerged for me that night, with and through Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s amazing performance.

UMS: What do you think audience members who aren’t of the Sufi faith or no little about Sufi music will get out of the performance?

FM: As my comments above have suggested, there is undoubtedly an aesthetic beauty and emotional power to qawwali as an art form. It’s a pleasure to experience, no matter what one’s religion, or if one has no religious disposition at all. For those who know that this is a form of music associated with Sufi devotionalism, I think it will expose them to an aspect of Islam and Muslim devotion that has played a very significant role in Muslim devotion in the subcontinent historically, and continues to do so to this day.

UMS: What do you think people should look out for in seeing Asif Ali Khan’s performance with UMS this season?

FM: One of the pleasures of live performances of qawwali (as with other genres of Indian vocal performance) is artist improvisation. The genre lends itself to vocal improvisation, all within the bounds of a rigorous tradition of ragas and beat. Although improvisation is caught on recordings of live performance, the ability to see it in creation, as a response to a given environment is something you just can’t get off a CD!

UMS: Can you suggest some musical selections from Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan that might give our readers an entry point into his music? What’s important to you or interesting about these selections?

This is a hard question because there are so many dimensions to Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s music. One, of course, is that of aesthetic pleasure; the joy of the music/composition. This is accessible to anyone. The other, is the content of the verses set to music. Nusrat performed compositions in Persian, Urdu, and Punjabi (among other languages). Each has an important place in his repertoire. Three stand out for me, one in each language:

Qawwali in Farsi by Hazrat Amir Khusro in Raga Khamaj. I am not fluent in Persian, so can’t speak to the content of the poetry being performed in this composition, but what I love about this qawwali is how it ties contemporary practice, in time and space, to the subcontinent and the reputed creator of the art form of qawwali. Amir Khusro is a thirteenth century poet who was a devotee of the Sufi saint Nizamuddin Auliya. Amir Khusro is buried in the shrine complex that emerged around the tomb of Nizamuddin Auliya in Delhi, and one can today visit his tomb, the shrine of his patron and Sufi master, and hear qawwali—usually poems in praise of the Sufi saint—in the precincts of his shrine. Khusro was a Sufi adept, as well as a gifted poet and music theorist. He is considered the father of Hindustani classical music, and it is through his own devotional practice that qawwali as a genre was born.

Main Jana Jogi de Naal. This is a Punjabi qawwali that draws on the poetry of the Sufi saint Bulleh Shah. The text is a Sufi poem that points to the hypocrisy of empty ritual, pointing to love (for the divine) as true faith. It’s an immensely evocative poem in its language and its allusions, and is performed with a level of emotion that conveys the conviction of the text, even if you aren’t a Punjabi speaker!

Modern qawwali by Allama Iqbal in Raga Bilawal. Allama Iqbal (Muhammad Iqbal) is among the most renowned Urdu poets of the twentieth century. This qawwali takes one his most famous poems, Shikwa (Complaint), and performs it in the genre of qawwali. Iqbal’s poem is a political tract about the place and status of Muslims in the early twentieth century, rendered as a complaint to God. It is a brilliant poem that captures an important moment in South Asian history. I like this qawwali not only for its beautiful verse, but for the ways it exemplifies how flexible and adaptable the qawwali genre is, particularly in the hands of someone as talented as Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan.

Did you listen to Farina’s music selections? Were you familiar with qawwali before? What do you think?

UMS brings Asif Ali Khan to Ann Arbor in conjunction with UMMA’s exhibition of Doris Duke’s Shangri La: Architecture, Landscape, and Islamic Art on view January 25 – May 4, 2014. Learn more about the exhibition.

Qawwali: More Familiar Than You Think

Photo: Asif Ali Khan Qawwali Music of Pakistan ensemble. They perform in Ann Arbor on March 21st, 2014. Photo by Cynthia Sciberras.

Qawwali is a kind of Sufi devotional music that is popular in South Asia, especially in parts of Pakistan and India. It has existed for at least 700 years. Although it is often referred to as a meditative and trance-inducing music, qawwali can be equally fast-paced and rapturous. The main themes of qawwali are love, devotion and longing for the Divine.

Listeners acquainted with North Indian classical music or the Whirling Dervishes of Turkey may hear something familiar. Although there are obvious differences, in many ways qawwali is comparable to North Indian classical music, Hindustani raga. India and Pakistan, as well as many other areas in South Asia share similar aspects of music due to shared history and similar instruments such as the harmonium and tabla. In both Hindustani classical music and qawwali, group performances are the norm; however, in qawwali, there is often a lead singer and a chorus that claps with the percussion during the pieces. In both kinds of music, one will usually hear each song progress through a slow introductory alap followed by a quicker development. Another similarity is the extensive vocal improvisation featured in both.

Concert duration will be another familiar feature where listeners can compare Hindustani classical music and qawwali music. Especially in contrast to music in the Western world, the length of time spent on each piece, as well as the concert’s total length will normally continue much longer than the duration expectations for usual concerts heard in the United States. Part of the reason for this length is that there are many different kinds of pieces that traditionally make up qawwali. Another reason is that the words are repeated with variations in order to bring out deeper meanings, as well as to lead the listener and performer into a trance, hal, which would then lead to spiritual enlightenment, fana.

Below are 5 different kinds of qawwali songs that you might hear with examples you might listen to.

1. A hamd is a song praising Allah. Traditionally, this is a piece used to begin a qawwali performance. An example is “Be Parwah de Naal Newn laa lia,” sung by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan.

2. A naat is a song praising the Prophet Muhammad, which usually follows the opening hamd. Asif Ali Khan can be heard here singing “Madine ke Waali Madine Bulalo.”

3. The next song to be sung would be a manqabat, which either praises Imam Ali or one of the Sufi saints. For an example, listen to Rafiq Dildar sing “Ali Ali Maula.”

4. A genre of song sung less often is the marsiya which is a lamentation over the death Imam Husayn’s family during the Battle of Karbala. Below, you can listen to an example, “Hussain Hai,” sung by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan.

5. One last major type of qawwali should be mentioned. A ghazal is a love song, and while the poetry’s meaning is spiritual, the lyrics often sound quite secular to an outsider. Many ghazals speak of the suffering of being separated from the one you love. Here is a recording of Abida Parveen, a female Pakistani vocalist, singing “Yaar Ko Hamne Ja Ba Ja Dekha.” It is important to note that in general, women do not sing qawwali, and even when the songs are sung, women sing in a different style than the men, as can be heard in this recording.

After listening to some of these pieces, it is impossible not to appreciate the entrancing quality of this music with its winding melodies and expansive qualities. Come listen to more on Friday, March 21st at 8 pm at Rackham Auditorium! The Asif Ali Khan Qawwali Music of Pakistan ensemble will be performing more beautiful, rousing music. While you’re there, see if you can pick out what kind of song is being sung!

Sources:

- Abbas, S. B. (2007). Risky knowledge in risky times: Political discourses of qawwali and sufiana-kalam in Pakistan-Indian Sufism.The Muslim World, 97(4), 626-639.

- Farida, Syeda. (2012). Whirling Dervishes, soulful qawwali. The Hindu.

- Huda, Q. (2007). Memory, performance, and poetic peacemaking in qawwali. The Muslim World, 97(4), 678-700.

- Kugle, S. (2007). Qawwali between written poem and sung lyric, or… how a ghazal lives. The Muslim World, 97(4), 571-610.

- Tanzeel, u. R. (2013, Sep 03). Qawwali: Sufi devotional music. The Financial Daily.

- Qureshi, R. B. (1981). Qawwali: Sound, context and meaning in Indo-Muslim Sufi music. (Order No. 8217377, University of Alberta (Canada)). ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, 513-513 p.

Buena Vista Social Club is a Party Foul

Photo: Pedrito Martinez Group. The group performs with Alfredo Rodríguez Trio on March 14, 2014 in Ann Arbor. Photo by Petra Richterova.

Has this ever happened to you? You find yourself in a conversation with someone who knows a lot about music (and probably craft brewed beer, artisanal fermented foods, and expensive jeans). When the topic shifts to Cuban music you make the mistake of saying something like, “Oh I love Cuban music, I listen to Buena Vista Social Club all the time.” A smirk quickly appears on the face of your friend. All of the air goes out of the room. You know you have said something terribly wrong, but you are not sure exactly what.

If this has ever happened to you (or even if it hasn’t), you need to get tickets to come see Alfredo Rodríguez and Pedrito Martínez, two talented young musicians from Cuba who are reworking the Cuban sounds they grew up with.

“The Special Period”

First a disclaimer: I love Buena Vista Social Club. I do not care who smirks at me for it. But here is a little context. Buena Vista Social Club appeared in 1997 during what Cubans call “The Special Period.” Cuba’s socialist economy entered a severe crisis after the fall of the Soviet Union, as trade and assistance from Communist Europe suddenly vanished. Meanwhile the United States tightened its trade embargo. In response, the Cuban government shifted its economic strategy towards the development of tourism and the marketing of Cuban culture to international audiences. At the same time, the Clinton administration loosened restrictions on travel by Cuban artists to the United States. Buena Vista Social Club – a phenomenon which includes an album, a film, and many international tours – was the most commercially successful cultural enterprise of this new landscape. And it is brilliant. But the vision of Cuba that Buena Vista Social Club sold was one where time had stood still: a world of crumbling Art Deco buildings, well maintained vintage automobiles, and picturesque elderly black performers playing exactly the same music that they had played in the decades before the revolution.

So the knock on Buena Vista Social Club is that it reintroduced international audiences to a Cuba that no longer existed. This was our loss, because the music that had evolved in Cuba in the 1970s and 1980s, and was still evolving in Cuba in the 1990s and beyond, was pretty special. This is where Alfredo Rodríguez and Pedrito Martínez come in. They came of age in Cuba in the Special Period, when “Chan Chan” played in every bar in Madrid and Paris, but that sort of music was only really heard in hotels catering to tourists in Cuba. Their music gives a glimpse of what was happening in Cuba as the elderly musicians of Buena Vista Social Club conquered the world.

Chan Chan:

Music: A hallmark of Cuban socialism

One of the amazing things about music in Havana in these years was the extent of conservatory training; expanded access to music education was a hallmark of the cultural policy of Cuban socialism. So it was not uncommon for popular musicians in Cuba in these years to have advanced classical training. Born in 1985, Alfredo Rodríguez, the son of well-known popular musician and television personality, grew up in this system. He moved back and forth between the classical training of the conservatory and the popular music he played with his father. Eventually he found his niche in the world of jazz. Cuban musicians from had been experimenting with jazz since the 1970s. By the 1990s, after the much-publicized visit of Dizzy Gillespie to Cuba, the top players in the Cuban jazz world became part of the international circuit. Some defected, but others simply enjoyed the new freedom to tour outside Cuba that came with the new economic strategies of the regime. Rodriguez was playing in Montreaux in 2006 when he met Quincy Jones. Then he was playing with his father’s band in Mexico when he decided to cross the border into the US to work with Quincy.

A second important musical trend in Cuba after the revolution was shifting official policy towards Afro-Cuban folkloric music, percussive styles like rumba, abakua, and batá (the music played during Santería ceremonies). African slaves and their descendants developed these styles of music in the context of spiritual practice and community life not the music industry. In the 1960s and 1970s, the master percussionists of these traditions became employees of state folklore agencies, performing Afro-Cuban music on stage. In the 1990s, folklore groups and the state began selling this version of Cuban culture abroad too. Afro-Cuban cultural groups like Muñequitos de Matanzas began travelling to the US. Pedrito Martínez grew up in this world, winning international competitions in Afro-Cuban hand drumming and entering the world of professional musicianship on international tours with Muñequitos de Matanzas. He also won international exposure as part of a rumba ensemble that appeared in the film Calle 54 (2000). We cannot link to video of this segment because of copyright, but it is worth watching on Netflix if you can.

Muñequitos de Matanzas during their first US tour in 1992:

Timba is perhaps the most important of all the musical innovations in Cuba during the Special Period. Timba was a dance music popular among the urban, Afro-descended Cubans who found themselves increasingly disenfranchised by the shifting economic strategies of the socialist government. Timba lyrics adopted street slang and discussed taboo subjects including the informal economy of hustling, linked to the growth in tourism. Built of the same materials as salsa, timba followed a distinct path. Most important was a restructuring of the classic Cuban dance music around explicitly Afro-Cuban rhythms and a much more experimental approach to rhythm in general. Batá or rumba variants were as likely to form the central rhythmic arguments as the classic son tumbaos. Timba also built on on the funk-fusion sound of the experimental jazz group Irakere.

NG La Banda Santa Palabra:

Bacalao con Pan:

Timba was the alter-ego of Buena Vista Social Club, young and edgy, informed by Cuban jazz, by Afro-Cuban folklore, and often played by musicians who had been trained in conservatories. The point is not that this music was more authentic, somehow free of the influence of marketing. The interplay of international promotion and local musical scenes helped produce a wide range of musical options in and around Cuba over the past twenty-five years, including a dizzying array of musical talent. The upcoming UMS concert offers a glimpse at this world. Alfredo Rodríguez is a conservatory trained technical virtuoso, with a background in Cuban popular music, who grew up idolizing Kieth Jarrett. He experiments at the boundaries between straight ahead jazz and Cuban jazz.

…y bailaría la negra:

Pedrito Martínez is a percussionist who played with Munequitos de Matanzas when that band was already making regular commercial tours around the world. He explores timba and Cuban funk fusion in a small quartet format, just a keyboard, bass, and bongó player to accompany his congas. Both musicians continue to rethink the music they grew up with in conversation with the wide range of international musicians and styles they embody.

Que palo:

Please do not smirk the next time someone tells you that they love of Buena Vista Social Club. Just smile, and tell them about the concert you just saw by Alfredo Rodríguez. Nod and lend them your copy of Pedrito Martínez’s new record with its amazing cover of of Robert Johnson.

Travelling Riverside Blues:

Artist Interview: Cuban Pianist Alfredo Rodríguez

Photo: Alfredo Rodríguez. Photo by Anna Webber.

Alfredo Rodríguez is a Cuban pianist and composer. He was born in Havana, Cuba, in 1985. With a well-known Cuban singer as his father, it is no wonder that he has been surrounded by music his entire life. He started studying at the Manuel Saumell Cuban Conservatory at the age of 7, and has been playing and creating music ever since.

Alfredo spent some time talking with us about his experiences in Cuba and in the United States, his thoughts about a musician’s life, and his upcoming work. He’ll perform in Ann Arbor on March 14, 2014 as part of a unique double-bill with Pedrito Martinez Group.

Annick Odom: We know that you’ve played in Ann Arbor and Detroit before, but we’re really excited to have you playing for the first time with UMS in March. Your work draws on jazz and Cuban music traditions. How do you balance these in your own music?

Alfredo Rodríguez: Well, I started as a part of his [my father’s] band when I was very young, about 13. We used to play popular music, music from the traditions of Cuba and his compositions as well. I combined that kind of performing, that kind of ambiance, with the classical school.

In Cuban music, there is a lot of improvisation, but I didn’t know much about improvisation in classical music at that time. My uncle gave me an album called The Köln Concert by Keith Jarrett [the legendary jazz pianist], and that got me into improvisation.

I was used to Cuban traditional music and classical composers like Johann Sebastian Bach, and also to Latin composers. After that CD though, I found the music of many of the pioneers of the be-bop era, a lot of different musicians, mostly from the United States. I was falling in love with the way those composers and instruments created music.

AO: We presented Keith Jarrett in 2000! What exactly about that recording drew you in so much? What made you so excited about improvisation?

AR: Well, my uncle gave me that CD with an idea in mind, because he was not very involved in piano music. He gave me that CD because he knew that I was very into that world. But I wasn’t expecting anything it. I just put it on. It was a great introduction for me because Keith Jarrett had that touch and that knowledge about classical music, and he shows a lot of those influences in his playing. It was a good introduction for me to improvisation and jazz music, too, of course.

AO: You said that you played a lot with your father while growing up and that you played a lot of popular music in Cuba. How would you say that you’ve individualized yourself from previous generations of musicians from Cuba?

AR: I guess I would say that [the musicians in my generation] are changing every day. We have different experiences every day. [My generation] grew up in a different situation than the generations before us in Cuba. We had different problems, different ways of living, [different] points of view. And of course those differences are the reasons that music changes too.

What I like to do with my music is to just express the present, just express how I am feeling, what I am going through in that exact moment. I guess what I am trying to say is that everybody always has something to say, and it is always different for everybody. And that kind of honesty is what I look for in terms of music, and in terms of living my life.

So it’s very simple for me, I just try to express who I am when I play my music and compose. I try and show my [Cuban] roots and also the transculturation that I have been living since I have been here in the United States.

AO: Do you find yourself playing any differently since you moved to the US or do you play pretty similarly to when you lived in Cuba?

AR: No, I’ve definitely changed. The United States is a different country with different culture, which has been a very positive process for me in terms of learning.

[Cuba] is an island, and due to the country’s political history we have been only around Cubans for more than 50 years. The culture that we have been creating for so many years is very unique and powerful because we are surrounded by Cubans, but at the same time, it’s contradictory because we haven’t had the opportunity to have confrontation and transculturation with different cultures.

I wanted to know different cultures and meet different people with different points of view so that I could incorporate all of that into myself and reflect it in my music.

AO: Let’s talk about your upcoming concert here in Ann Arbor. Who will be coming with you? What will you perform? Can you also talk a little bit about your upcoming album?

AR: Actually I am releasing my next album The Invasion Parade on March 4th, which is going to be very, very close to the concert [in Ann Arbor on March 14]. I am going to be featuring the same trio that I had for my album at the concert. We are featuring different artists, but the main trio that I perform with is Peter Slavov, a Bulgarian bass player, and Henry Cole, a drummer from Puerto Rico.

We are going to be performing the music on this upcoming album as well as music from the past. But to be honest, music is very natural and spontaneous for us, so we just like to play songs that will fit in the moment that we are living.

It’s difficult to say exactly what songs we’ll play or even what the music is going to sound like. I guess what I mean to say is that we have the message that we want to tell people: 70% of my music is improvisation, and the other part is rhythm. So it’s kind of unexpected, and in that way, we learn more from ourselves.

AO: You’re sharing the bill with Pedrito Martinez. Have you ever played with him before?

AR: It’s very funny because Pedrito is part of my album [The Invasion Parade], too. I love his playing! Pedrito is one of the musicians coming out of Cuba that I admire so much because of his incorporation of our culture into his vocals and percussion. And speaking of my album, it also features Esperenza Spalding, and horn players from Cuba and Puerto Rico. But yeah, speaking of Pedrito, we have a really, really close relationship in both in terms of music and friendship.

AO: It seems that you are already thinking a lot about the upcoming months, but where do you see your music going even further into the future?

AR: That is a good question. To be honest, I don’t think too much about the future. What I can share with you is something that I’ve been working on since the past, until today, which is creating music.

I am also currently writing a lot of music for the symphony. The premiere of my first symphonic work will be this year in November, and I will be performing one of my compositions with an orchestra at the Barcelona Jazz Festival. And I’m working on new music for my trio and my upcoming CDs.

I do it [compose music] because I just need it. It’s like water for me. If I am inspired, I write something. I’m just composing music, doing what I like to do. I feel very fortunate about that because I just have the opportunity to live from what I love to do, and I am very grateful for that.

Interested in more? Check out Alfredo’s new album or get tickets to his performance with Pedrito Martinez Group in Ann Arbor on March 14, 2014.

The Power of Music in Mali

Photo: Bassekou Kouyate and his band Ngoni Ba. They perform in Ann Arbor on February 7, 2014. Photo by Jens Schwarz.

Music is culture and therefore it is a medium for social and political change. It is a potent organizational tool, one that can be used as a rallying cry to action or as a soothing message that brings hope to those struck by disaster. As a music student here at the University of Michigan, I have taken an American musicology class that focused in part on music’s ability to bring people together in various circumstances. Music helps listeners focus on what a better future will be like, but it also evokes what disaster and war can destroy. It is a strong reminder of the best and worst that humans can do to each other. In this class, examples of the power of music here in the U.S. were countless. Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” in 1939 borrows its words from Abel Meeropol’s poem which uses symbolism to speak about racism and lynching. Woody Guthrie’s “This Land is Your Land” is a veiled political message that champions socialism in the 1940s. Bob Dylan’s “The Times they are a-Changin” in 1964 and “We Shall Overcome,” both became calls to action for the Civil Rights Movement.

The upcoming UMS concert “One Night in Bamako,” performed by two Malian musicians, made me wonder what musicians in Mali had to say about their country. How are these musicians sharing their culture with the rest of the world through music, and what are they critical of in their country? Given that the political unrest and tensions between different ethnic groups in Mali persist, even after a fragile peace has been restored, I wanted to find out what musicians had to say about events in their war-stricken country. I wanted to see what musicians had to say about the events in the last two years. During the al-Qaeda’s takeover of northern Mali, a very extreme version of sharia, the religious laws and morals of Islam, was instituted. This forced many rules upon unwilling citizens and dire punishments were handed out when the rules were not followed. Drinking and smoking were forbidden, all women were required to cover their heads, and any secular music was banned. Instruments were smashed and confiscated, and musicians were threatened with beatings and mutilations if they continued making music.

Music during violence

Mali music is internationally known for its diverse traditions and talented musicians. The country is even cited as creating some of the first music to inspire the blues. Music is part of many daily rituals in Mali, and praised singers and musical storytellers known as griots sing at birth ceremonies, weddings, and funerals. They do much more than entertain, however; they are the oral historians who know the local legends and family stories, and they are charged with passing them down to the following generation. Yacouba Sissoko, a well-known Malian griot says that the griot is a “person who creates cohesion between people, a kind of cement in Malian society.” The importance and ubiquity of music in Mali’s everyday life meant that the loss of music was especially difficult for the community. Even for musicians in southern Mali, the ban was crippling; many music festivals are held in the North, and if musicians had family in the North, they were worried that performing would put them in danger.

Despite the banning of music, many musicians worked tirelessly during the turmoil to bring hope to the people of northern Mali, and to bring the attention of other countries to Mali. In many ways , instead of silencing Mali, the ban seems only to have fortified music’s power to reunite and restore the country. Rapper Amkoullel was writing songs even before the coup brought problems in Mali to the world’s attention. His song “S.O.S.” talks about the dire situation in Mali and the tension between multiple cultural groups there. After the outbreak of violence, he and many other musicians came together to create the song “Tous UN pour le Mali”, which calls for international assistance to be given to Mali. Even after an unstable ceasefire was reached, he wrote “Vote!” to remind Malians of the importance of their voice in the election. Oumou Sangare put out “La Paix Au Mali” early in the conflict, promoting unity and order. Bassekou Kouyate, the ngoni player and bandleader who is coming to Ann Arbor in several weeks, released “Jama ko” which asked for harmony and tolerance during the crisis. In a particularly well-known responses to the violence, singer-songwriter Fatoumata Diawara gathered a large group of Malian musicians, including Vieux Farka Touré, Amadou et Mariam, and Toumani Diabaté to record a song entitled “Mali-ko” calling for peace.

Mali-ko

Music festivals also worked together to keep Malian music alive and in the news. Two of the best known and most highly ranked music festivals in Africa, Festival au Desert and Festival sur le Niger, were disrupted during the struggles in Mali. Festival au Desert was forced to cancel and move its location from Timbuktu, even for its upcoming 2014 edition, due to security issues. For the 2013 and now the 2014 festivals, the festival has been renamed “Le Festival au Desert in Exile”, and organizers have created various caravans of artists who will travel internationally until they are able to return to Mali. Festival sur le Niger, due to its Southern location, has been able to hold its festival this year and invited Festival au Desert to have a performance there as well. These two festivals have been a way to continue sharing Malian culture with the rest of the world, provide income for Malian musicians, and bring happiness and hope to Malian citizens.

It’s not only musicians working through song that are working to create change in Mali; international organizations and individuals are also stepping in. In July 2012, Oxfam International, a confederation working against poverty, backed a performance in Bamako entitled “Mali Music Unplugged” bringing attention to the crisis in Mali. More recently, Malian Music in Exile is received funding for They Will Have To Kill Us First, a documentary about how musicians lived during the ban on music, featuring musicians such as Fatoumata Diawara and Bassekou Kouyate.

Return of Music to Mali?

The fight for music in Mali is not over yet. Many musicians are still in exile, frightened by the violence, and have been slow to return to music-making in Mali. Arab and Tuareg musicians, both ethnic groups which have been strongly linked to the Islamist rebels, are concerned about retaliations and punishment by other civilians as well as the Malian Army. In addition, due to a renewed countrywide state of emergency, gatherings of more than 70 people are still banned, making live performance of music difficult.

According to Rokia Traore, a Malian musician who was recently interviewed by PBS, artists want to show that despite the wars and poverty portrayed in the media to Western countries, there is more. She points out that there is a normal life for people living in Mali, filled with joyful things, and that people do not see themselves as victims. She also says that music will start again, and that more songs have been written about what has happened in Mali, than would have if there had not been so much fighting. “You cannot stop that in a whole country,” she says, “especially one like Mali.”

Fatoumata Diawara and Bassekou Kouyate &Ngoni Ba perform in Ann Arbor on Friday, February 7, 2014. Both artists have both been outspoken in their music about their desire for peace in Mali.

Interested in hearing more music? Listen to this Spotify playlist (via The Guardian).

Educator Conversations: One Night in Bamako

Editor’s note: This post is a part of a series of conversations between educators in the K-12 community. Educators will offer suggestions and answer questions about integrating UMS School Day Performances or the arts into classroom curriculum, as well as share advice on organizing a field trip to UMS. To volunteer to be a Teacher Lobby Moderator e-mail umsyouth@umich.edu. Or, check out other Educator Conversations.

This week’s questions:

- Who are these two artists, Bassekou Kouyaté and Ngoni Ba?

- How should I prepare my class for the performance?

- Bamako? What? Where? And who cares?

- Isn’t taking a class on a field trip too much trouble?

This week’s moderator: Jeff Gaynor. Jeff has been teaching for 35+ years, 20 years at Elementary, and the last 15+ at Clague Middle School, where he teaches Math and Social Studies. He integrates music and art into the curriculum, often prior to field trips, or by bringing guest artists in his classroom. Jeff is on the UMS Teacher Insight Committee has an interest in classical, jazz and world music. He has participated in month-long teacher study trips to Belize, Turkey and South Africa.

This week’s moderator: Jeff Gaynor. Jeff has been teaching for 35+ years, 20 years at Elementary, and the last 15+ at Clague Middle School, where he teaches Math and Social Studies. He integrates music and art into the curriculum, often prior to field trips, or by bringing guest artists in his classroom. Jeff is on the UMS Teacher Insight Committee has an interest in classical, jazz and world music. He has participated in month-long teacher study trips to Belize, Turkey and South Africa.

Q: Who are these two artists: Bassekou Kouyaté and Ngoni Ba?

Ha – this was my first question – and I can save you the same embarrassment. Bassekou Kouyaté is the lead musician. He plays an ancient traditional stringed instrument, like a lute, but he has also modernized it in amazing ways. This instrument is called the ‘ngoni.’ “Ngoni Ba” is the name of the band he leads. Check them out.

Q: How should I prepare my class for the performance?

It’s important that students look forward to the trip with anticipation. The level of academic preparation depends on the grade, subject, and how much time you can spend (pressing issue, I know). At a minimum, I go through the UMS Learning Guide and choose 1 or 2 activities to do with my students. Also very helpful, especially with unusual instruments or genres, is to play audio or video clips in class, and have a discussion to focus attention on how this music is alike or different from other music they have heard.

You can find videos on YouTube, and the Guide has more suggestions. Seeing or listening to the music in your classroom isn’t the real thing, though curiously, the appreciation for the live performance will be increased if students have seen the performer before hand, if on a screen. At a minimum go to the UMS web page and click on “Listen & Learn.”

Of course, the more curriculum connections you make, the more students will take out of the live performance, which leads us to:

Q: Bamako? What? Where? And who cares?

“‘I mean, what is music itself? Music is everywhere, every day. If you’re gonna genuinely do that, you prohibit all sound because music is in language, it’s in everything. It’s totally abhorrent to any musician to be told they can’t play music… It’s a very particular interpretation of the Koran that prohibits all music,’ said Damon Albarn, an Africa Express co-founder.”

Quote from BBC News.

And suddenly, music is more than just music. And Bamako, the capital of Mali, in the horn of Africa, is more than some far away place. And we are teachers – it is our job to show the commonalities and the uniqueness of people in all parts of the globe.

Explore geography – with a map of West Africa, and a map of Mali, point out the the capital of Bamako, the fabled city of Timbuktu (Tombouctou), the Niger River, and the seven countries that border Mali. Find images of these places.

Read folk tales from Mali (or West Africa) as folk tales are universal and also particular. Point out that Bassekou Kouyaté is a griot – a historian and storyteller, through his music.

Most of the northern tier of Africa is heavily Muslim, as is Mali. This is part of their culture and influences the music. Islam is one of the five world religions covered in the Ann Arbor middle school social studies curriculum and may be integrated during the study of Islam or the Middle East or Northern Africa.

The quote that led this section was in response to a crisis in Mali during which Islamic fundamentalists took control of the northern part of the country. France (Mali was a French colony until 1960) then intervened militarily. This is a vital area for research with parallels and ramifications throughout the region.

Q: Isn’t taking a class on a field trip too much trouble?

No! It does take preparation but the benefits far outweigh the effort. And it will be an experience your students will remember for years and link to their classroom learning.

As an elementary teacher, and now middle school social studies teacher, I feel it is eminently important to help students link classroom experiences to the world around them. Reading about a country, or culture, or listening to a CD is one thing; attending a live concert is a visceral experience that brings learning to another level. This music may be different, but music is universal.

UMS keeps the cost of their School Day performances low. As I teach in Ann Arbor, I also choose to have my students travel on the City Bus – a $1.50 round trip, with the benefit that they get more real life experiences. I ask parents to pay the cost (under $10) or what they can, and the School PTSO makes up the difference.

Check out the AATA website for route maps and schedules. You do not need to contact them ahead of time. Do have students go to the back of the bus while you pay the driver for everyone. Do not have each student pay his or her own fare as it takes much too long.

I prepare my class not only for the concert but for taking the bus and walking through city streets: how to wait for and behave on the bus, how to leave space on the sidewalk to allow other pedestrians to pass, how to cross the street – all real life skills that they take seriously. They understand they are now off school property and the expectations are obligatory, not arbitrary. Of course I also prepare them to be good audience members, referring to the UMS Learning Guide for valuable reminders.

In fact the Learning Guide has important and worthwhile resources for pre- and post-concert links, resources and activities. Do take the time to read through it.

Do you have questions or comments for Jeff about his approach to this performance or about teaching through performance more broadly? Share your responses or questions in the comments section below.

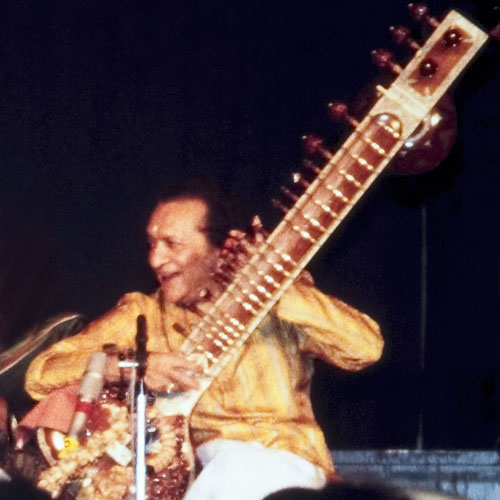

UMS Playlist: Pandit Ravi Shankar: A Retrospective

This post is a part of a series of playlists curated by UMS staff, artists, and community. Check out more music here.

Ravi Shankar in 1988. Photo by Alephalpha.

For many, the name Ravi Shankar is synonymous with Indian music. Indeed, in his nearly 70 year career he performed Hindustani (North Indian) classical music in nearly every corner of the globe, positioning him, in the words of India’s Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, as “a national treasure and global ambassador of India’s cultural heritage.” But his staggering body of work did not only pave the way for other Indian musicians. His innovations and undeniable presence on the global stage helped create the genre we now know of as “world music,” which continues to impact on cultural interaction and the way we experience culture in the modern world.

More than that, though, Pandit Ravi Shankar taught us what it means for an artist to be a true innovator. Even within the historically established tradition of Hindustani classical music, he constantly pushed forward, looking for new directions and new contexts for his music. Still, throughout this process he never lost sight of the tradition from which he came. This is the true nature of innovation: to retain the utmost humility before one’s roots, but with the fearlessness to take risks and try something new. In 2005 I had the pleasure of hearing Pandit-ji speak prior to a concert at Hill Auditorium. When asked what music his was listening to for inspiration, he answered, “I only listen to my own music.” Even then, after 60 years of recording, touring, and composing, he was still evaluating his work and striving for something more. He was 85 years old.

In this small collection from Ravi Shankar’s substantial discography, I have tried to paint a picture of the breadth of his musical life. From his early travels abroad with his brother, Uday Shankar, to his legendary performance at the Monterey Pop Festival. From his ground-breaking Concerto for Sitar and Orchestra to his collaborations with Philip Glass. From his Academy Award-nominated score for the film Gandhi to recordings he made only months before his death. His was a career that not only served as a link between India and the world, but that defined what it means to be a musician on the world’s stage.

Interested in learning more? Check out the program from Ravi Shankar’s performance in Ann Arbor in 1996.

What did you think about this playlist? Share your thoughts or song suggestions in the comments below.

This Day in UMS: Ravi Shankar

Editor’s Note: “This day in UMS History” is an occasional series of vignettes drawn from UMS’s historical archive. If you have a personal story or particular memory from attending the performance featured here, we’d love to hear from you in the comments.

December 11: Anniversary of Ravi Shankar’s Death

Legendary virtuoso sitarist, composer, teacher, and writer, Ravi Shankar was India’s most esteemed musical Ambassador and a singular phenomenon in the classical music worlds of both East and West. A prolific composer, he composed numerous traditional ragas and talas, as well as many works involving western collaborations, including two concertos for sitar and orchestra for violinist Yehudi Mehunin and collaboration with Philip Glass, including the multi-artist work Orion, which opened the 2004 Cultural Olympiad in Greece. The New York Times called him the “Sitarist who introduced Indian Music to the West.”

UMS first had the honor of presenting Ravi Shankar in April 1996 in Rackham Auditorium. The program pictured above is from a solo performance in Hill Auditorium in September 2004.

UMS Playlist: “Bachs” & “Beethovens” of Indian Classical Music

This post is a part of a series of playlists curated by UMS staff, artists, and community. Check out more music here.

Photo: The Manganiyar Seduction performances kick off University of Michigan “India in the World” theme semester on October 26-27, 2013.

“India has emerged on the world scene in entirely new ways: as one of the world’s most vibrant economies; a key player in geopolitics; the world’s largest democracy; home to the world’s largest “middle class”; the site of one of the world’s largest and most vibrant film industries; a contributor to global trends in art and aesthetics; and “home” to well-established and significant immigrant communities around the world, including the United States.” So begins the description of this winter’s “India in the World” U-M theme semester.

While The Manganiyar Seduction (a “seduction of the spirit” that begins quietly with a solitary desert fiddle, but builds to an ecstatic eruption of sound, light, and color) highlights the folk music tradition of desert musicians from Rajasthan, India, we asked John Churchville, member of Ann Arbor-based Indian classical music ensemble Sumkali, to highlight his favorite Indian classical music picks.

Take a listen to his playlist on Spotify:

John Churchville is the founder and tabla player for Indian fusion group Sumkali. He is also the Music director at Go Like The Wind School in Ann Arbor and holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in World Music Performance fromCalifornia Institute of the Arts. He is currently persuing his Masters in Music Education degree at the U of M. He hosts a monthly Indian Music Night at Crazy Wisdom Tearoom downtown Ann Arbor and is the music director for the Ann Arbor Kirtan spiritual chanting group is the founder and tabla player for Indian fusion group Sumkali. He is also the Music director at Go Like The Wind School in Ann Arbor and holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in World Music Performance fromCalifornia Institute of the Arts. He is currently persuing his Masters in Music Education degree at the U of M. He hosts a monthly Indian Music Night at Crazy Wisdom Tearoom downtown Ann Arbor and is the music director for the Ann Arbor Kirtan spiritual chanting group

John Churchville is the founder and tabla player for Indian fusion group Sumkali. He is also the Music director at Go Like The Wind School in Ann Arbor and holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in World Music Performance fromCalifornia Institute of the Arts. He is currently persuing his Masters in Music Education degree at the U of M. He hosts a monthly Indian Music Night at Crazy Wisdom Tearoom downtown Ann Arbor and is the music director for the Ann Arbor Kirtan spiritual chanting group is the founder and tabla player for Indian fusion group Sumkali. He is also the Music director at Go Like The Wind School in Ann Arbor and holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in World Music Performance fromCalifornia Institute of the Arts. He is currently persuing his Masters in Music Education degree at the U of M. He hosts a monthly Indian Music Night at Crazy Wisdom Tearoom downtown Ann Arbor and is the music director for the Ann Arbor Kirtan spiritual chanting group

What did you think about this playlist? Share your thoughts or song suggestions in the comments below.

Did you know? The Manganiyar Seduction

Photo: The Manganiyar Seduction on stage.

The Manganiyar Seduction has been described as “Equal parts rock concert, global music performance, and dazzling theatrical experience.” Director Roysten Abel experimented boldly with the Manganiyars, desert musicians from Rajasthan, to create a dazzling union between the Manganiyars’ music and the visual seduction of Amsterdam’s Red Light District.

The performances on October 26-27, 2013 kick off University of Michigan “India in the World” theme semester.

Did you know that…

1. The word Manganiyar can be translated to mean ‘those who ask for alms.’ This is because on various religious and social occasions the musicians go to patrons’ houses and perform. In turn, they are rewarded with such items as grain, animals, or cash. (via)

2. The kamaycha is an indigenous instrument of Rajasthan and is also one of the rarest instruments found in India. It is a bowed string instrument, which is often made of mango wood and covered with goat skin. (via)

3. The music played by the Manganiyars is a mix of Pakistani and classical Hindustani traditions. Many of their ragas are based on Hindustani ragas, while their text is based on Sindhi surs, poetic texts associated with Pakistani music. (via)

4. A game called Kakadi was often played by Manganiyars at patron family gatherings in the past. In this game, the musician uses the ragas to lead the patron to a hidden object. The six ragas considered indigenous to the Manganiyars correspond to the cardinal directions of north, south, east, and west, as well as up and down. The game is becoming less common as musical expertise among patrons decreases, but historically at least one member of the family has been taught how to play the game. (via)

Have you ever attended a global music performance? What got you interested in attending? Share your experiences below.

Our Interview with Kodo’s Jun Akimoto

Photo: Kodo in performance. Photo by Takashi Okamoto.

Kodo perform in Hill Auditorium on February 15, 2013. With over twenty visits to Ann Arbor over the years, Kodo return with a brand-new performance that includes new visual flair alongside its high-energy percussion, elegant music, dance, and the striking physical prowess needed to sustain a precise yet powerful sound.

We chatted with Jun Akimoto, the group’s company manager, about the power of taiko drums, Kodo’s mission to represent the living folk performing arts of Japan, and what they’re looking forward to in their upcoming visit to Ann Arbor.

UMS: Could you talk about the choreography of Kodo performances? What does it mean to be a part of sharing this rich Japanese tradition?

Jun Akimoto

Jun: Our artistic director Mr. Tamasaburo Bando, is responsible for the artistic direction of Kodo, and he has been working with us for 12 years. Actually, it does not seem to sound appropriate for us to call the movements of Kodo “choreography” since the company’s focus is Japanese drumming, not dancing. Having said that, Mr. Bando, is a renowned Kabuki actor and dancer. His rich and profound philosophy and knowledge and technique of “body” have inspired Kodo immensely at the deeper level. Body movement techniques generally used in many of the Japanese performing arts have something in common beyond the different forms and styles, so the performers of Kodo often feel a kind of cultural synchronicity in Mr. Bando’s comprehension about “body.”

UMS: Can you share your experience about the Kodo Village? How does living there enhance your craft?

Jun: Sharing time and place during the daily life in the Kodo village surely influences what the each member of the company thinks and creates. Particularly, Kodo is known for the collective beauty and unity of the performance. This unity comes from how members of Kodo live at the headquarters of Kodo on Sado Island.

In Japan, I think this sort of mental/physical connection has been cherished and inherited from the traditional way of life in the Japanese feudal societies of the past, which were mostly supported by agrarian communities. Sado Island is one of the rural regions that still retains the traditional ways of life. Kodo owes so much to Sado and the local people, because living there constantly reminds us that folk performing arts are an important part of the life of a community.

UMS: What are the different types of drums that will be used during the performance? What do some of the drums represent?

Jun: Japanese drums, or taiko, have a very simple structure, but they are also seen as the communication tools used between the gods and the people, nature and the people, and people and people. Taiko is a very popular instrument in Japan and is often found in most shrines and temples.

Some types were originally imported through China and Korea. Kodo uses several types and sizes of taiko on stage, but we always feel that the simple but beautiful (and very strong) instrument acts as a door that opens us to the nature. These drums are made of a wood trunk with animal skins tacked to the drum body. It is said that the gods reside inside the taiko and the harder the drums are played, the more pleased the gods become. And, most importantly the drums are the symbol of community and unification.

UMS: Your music is a powerful reflection of both the history and the future of Japanese performing arts. How to you hope Kodo will evolve in the years to come?

Jun: The history of taiko as part of the commercial performing arts is still young and in development when compared to other established Japanese professional performing arts with hundreds of years of history, such as Noh, Kyogen, Bunraku, Kabuki, etc.

Kodo prioritizes the direct connections with the actual living “folk” traditional performing arts found in many regions in Japan (often in countryside and unknown to outsiders). These folk performing arts solidify a community through ceremonies, festivals, and rituals. In the years to come, Kodo hopes to not only continue as a commercial performing arts ensemble, but to be true to direct voices of living folk performing arts.

UMS: What cultural message do you hope will resonate with the audience of Ann Arbor?

Jun: We are very fortunate and honored to have had a long relationship with Ann Arbor. As generations shift both in Ann Arbor and in Kodo, we truly hope that Kodo will continue to refresh, develop, and keep our good relationship between the people in Ann Arbor and Kodo. We are looking forward to performing “Legend” (our new production) in Ann Arbor very soon!

Tweet Seats: Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán

For our second tweet seats event, we saw Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán in Hill Auditorium

Meet the participants.

UMS: Tell us a little about you. If you have an online presence you like to share publicly, please tell us the relevant websites or user names/handles.

Matt Landry: I am a K-12 certified music teacher, a University of Michigan graduate, Detroit Symphony Orchestra intern, and saxophonist of the Akropolis Reed Quintet, a five-time national prize-winning classical music ensemble. I tweet from @akropolis5tet, and I help manage the ensemble’s website: www.akropolisquintet.com.

Jared Rawlings: I am a process-centered innovative teacher, and an emerging researcher. I tweet @Jared_Rawlings and my website is: www.jaredrawlings.com.

UMS: In one sentence, how would you describe your relationship with technology?

Matt Landry: I have a love/hate relationship with technology, enjoying its contribution to bettering life while wondering if it is making humans less human.

Jared Rawlings: My relationship with technology is necessary in order to build my personal/professional learning network.

UMS: Why did you decide to participate in this project?

Matt Landry: I decided to participate in order to further deepen this relationship. I wonder if being engaged electronically in a live performance will enhance or detract from the beauty on stage.

Jared Rawlings: I am always looking for new ways to include professional development – on demand.

UMS: To you, what does it mean to “be present” during a performance or another arts experience?

Matt Landry: To be “present” at a performance one must consider what the event will be remembered as. One must comprehend the magnitude of the live performance, clear the mind to listen and/or view, and have a perspective of the event while it is occurring. Looking back on events and their personal significance is important, but doing so at the time of the performance, to me, is being “present.”

Jared Rawlings: Being present means it’s a way of capturing the “lived experience” of the concert goer. Also, given the temporal nature of music, theatre, and dance the tweet seats project is a way of focusing in on this phenomenon that is exclusive to live arts in Ann Arbor.

Meet the tweets.

UMS: How did tweeting affect your experience of the performance; did you expect this effect or are you surprised by this outcome?

Matt Landry:

Jared Rawlings:

Curious about live tweeting during a performance? Sign up.

[LISTENING GUIDE] Introduction to Sarod

Ustad Amjad Ali Khan performs on February 16 in Ann Arbor’s Hill Auditorium.

The sarod is an Indian stringed instrument used mainly in North Indian (Hindustani) classical music. The sarod’s ancestry links to the Afghan rabab, which is a wooden Central Asian lute that is covered with skin. Similar to the sitar, its more well-known stringed instrument cousin, the sarod is a smaller stringed instrument that is held in the musician’s lap. The conventional sarod is a lute-like instrument with 17 to 25 strings. Of these, four to five strings are used to play the melody, while one to two are drone strings, two are chikari strings, and nine to ten are sympathetic strings.

The sarod is an Indian stringed instrument used mainly in North Indian (Hindustani) classical music. The sarod’s ancestry links to the Afghan rabab, which is a wooden Central Asian lute that is covered with skin. Similar to the sitar, its more well-known stringed instrument cousin, the sarod is a smaller stringed instrument that is held in the musician’s lap. The conventional sarod is a lute-like instrument with 17 to 25 strings. Of these, four to five strings are used to play the melody, while one to two are drone strings, two are chikari strings, and nine to ten are sympathetic strings.

Claimed as “one of 20th century’s greatest masters of the Sarod” by Songlines World Music Magazine in 2003, Ustad Amjad Ali Khan is a sixth-generation sarod player in his family, which originated the esteemed Gwalior-Bangash gharana (a gharana is a system of social organization linking musicians or dancers by lineage or apprenticeship). It is said that Ustad Amjad Ali Khan’s ancestors had developed and shaped the instrument over several hundred years. Ustad Amjad Ali Khan was six years old when he gave his first recital on the sarod.

Ustad Amjad Ali Kahn on Improvisation in Indian Music & the Sarod

Listening guide

This year’s UMS listening guide serves as an introduction to the sarod and contains mainly Hindustani classical music featuring the instrument. You can also find more information on Ustad Amjad Ali Khan and sarod music on sarod.com

Raga Mian Ki Malhar with solo by Ustad Amjad Ali Khan

Ustad Amjad Ali Khan performs at Philharmonie Köln

Aman Ali And Ayaan Ali Khan perform at Modern School

Ayaan Ali Khan performs

Ustad Amjad Ali Khan performs Raag Maru Bihag

Interested in learning more about classical Indian music? Explore Meeta’s guide to improvisation in classical Indian music.

Photo and Audio Tour of Detroit’s Mexicantown

Editor’s note: The Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán return to Ann Arbor on April 1, 2016.

Mariachi Vargas is one of the most highly regarded ensembles in the history of mariachi. Founded in a small city near Jalisco by Don Gaspar Vargas in the 1890s, this band basically invented the modern mariachi, and five generations later, is still playing today.

To explore the music’s connection to our community, we asked WDET’s Martina Guzmán to give us a tour of Detroit’s Mexicantown, a neighborhood with over 100 years of history in the city. Check out the tour below, with images by Detroit-based photographer Erik Howard.

We also visited the LA SED (Latin Americans for Social and Economic Development) Senior Center in the neighborhood, where we heard many stories about the community importance of mariachi music.

“I was born and raised through Mariachis,” Lupe Guzmán says. “Don’t believe what I say, but Mariachi music is like medicine. Mariachi…you have one on side and another Mariachi on the other side, and they make you alive.”

Beatrice Gonzales was a singer when she was younger. She bought the dress in this photo in Mexico 35 years ago. She says that she is still in love with the tradition of Mariachis.

Arnulfo Guiterrez’ favorite song is “El Mariachi Loco.” It’s a LA SED Senior Center favorite for dancing.

UMS thanks AARP for coordinating ticketing and transportation for a group of LA SED seniors to attend the Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán performance.