Student Spotlight: Greg Hicks on How Max Raabe’s Tailored Tuxes Will Open Your Mind

Photo: Max Raabe rides his bicycle. He performs with his Palast Orchester on April 9, 2015 at Hill Auditorium. Photo by Marcus Hoehn.

Max Raabe and Palast Orchester are a well-groomed lot, both musically and visually — trained at the Berlin University of the Arts, tux-friendly, hair parted to one side — and that very sense of aesthetic perfection is what makes Raabe and company so unpredictable. While every tux is tailored to perfection and every stray hair is combed into place, Raabe’s creative persona throws the experience of the performance off-kilter in the best way.

The Raabe method of approach is to give a taste of vintage formality to a situation that might not require it. Past examples from Raabe include (but are not limited to):

- Using a condenser microphone to sing a live cover of Britney Spears’s “Oops…I Did It Again.”

- Wearing a tux while singing a cover of Queen’s “We Will Rock You.”

- Singing the 1930s hit “Dream a Little Dream” at music festivals.

Take a walk through Max Raabe and Palast Orchester’s photo gallery and you’ll get the same impression. You’re greeted with a photo of Raabe riding a bike — no-handed — through a city road whilst wearing his classic tuxedo, giving a casual grin to the photographer.

The Palast Orchester. Photo by Marcus Hoehn.

As you continue your photo exploration, you’ll find Raabe and the eleven other members of the Palast Orchester crammed into a paddleboat, instruments in hand, dressed in tuxes, casually floating along the lake. In further shots, Raabe is photographed mostly-submerged in the lake, head popping out, staring directly into the camera — still dressed in his tux. Oh, and there’s also a duck floating past him.

Why the constant throw-back attire, Mr. Raabe?

For one thing, cherry picking visual styles all the way back to the 1920s establishes an image to “not look the type” to perform contemporary music brands — allowing Raabe to shock and surprise audiences with well-orchestrated versions of relatively modern radio hits like “Oops…I Did It Again” and “We Will Rock You.” And Raabe isn’t the only notable artist to visually belong to one era of music while successfully surprising listeners with renditions of another.

Last year, pop sensation Lady Gaga showcased a similar visual deception — though in her case, pop aesthetic combined with jazz standards. Unlike Raabe, Gaga often exemplifies the most contemporary, dynamic image in her style, and on her latest record Cheek to Cheek, Gaga melded this persona into a record consisting of classic jazz hits sung with jazz icon Tony Bennett.

World-wide pop-rock sensation Robbie Williams (who often displays a “bad boy” stylistic persona) used a similar technique on his unexpected 2001 jazz standard cover album Swing When You’re Winning and again in 2013 with Swings Both Ways.

Pop diva Christina Aguilera went so far as to release an album of entirely original tracks in throwback production style on Back to Basics. Aguilera, Williams, and Gaga were all heavily praised for their surprising capabilities to sing in these unexpected genres.

And here on the flip side, we have Max Raabe, who takes a vintage image and displays his capabilities in the realm of popular music.

The visual foundation of the German old-style group is something that, upfront, audiences might take very seriously, given the formal vintage look. But upon observing the group’s surprising photoshoots and song cover choices, a new open-mindedness with a taste for the abstract and a quirky sense of humor might unfold.

When Max Raabe and the Palast Orchester performed previously in Ann Arbor, UMS gave fans the opportunity to sample their own vintage attire in an in-venue photo booth, and the same is encouraged this year. Come dressed in your best 1920s fashions, but don’t forget to bring your sense of humor as well!

Max Raabe and Palast Orchester perform at Hill Auditorium on April 9, 2015.

Interested in more? Explore even more audience photo booth photos from Max Raabe’s last appearance in Ann Arbor.

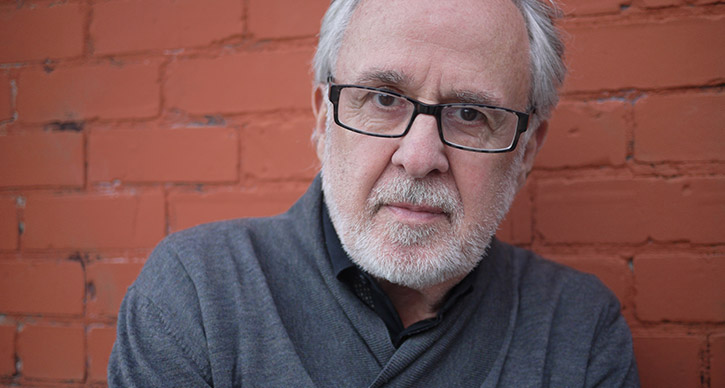

Resident Update: Writer Robert James Russell

Writer Robert James Russell is a UMS Artist in Residence this season. We’ve asked five artists from across disciplines to take “residence” at our performances and to share the work these performances inspire. Robert shares his experiences on dance, music, and his new novel below:

“When I applied for the UMS Artists-in-Residency program, my goal was to see performances and use that inspiration to craft a new novel. I’m beyond thrilled at the chance to experience wonderful performances and explore the role of music and dance in my work—both of which have always been crucial to my mental health, and to my ability to immerse myself in a project.

So far, I’ve seen the following UMS performances, all radically different from one another—and each has inspired me in vastly different ways:

- Ryoji Ikeda (superposition)

- Mariinsky Orchestra

- Compagnie Marie Chouinard

- eighth blackbird

See, this isn’t just writing a novel, coming up with a story and characters, but in this instance I am creating an entirely new place: a fictional island in Lake Superior, documenting the entire history of the island, of the people that lived (and, in the present of my novel, still live) there. Typically when I write I find some style of music that works for that story and I listen to the same record(s) over and over as I write, never growing tire of the repetition. In this instance, though, since it’s not just story, but history…and this immersion in different types of performances has been utterly liberating:

- superposition taught me, even through the wondrous noise, about the use of silence in my work.

- The Mariinsky Orchestra inspired me to embrace more bombastic/dramatic sections of the story.

- Watching the Compagnie Marie Chouinard showed me how to re-think interactions of characters, how they meet in the story, but also how these characters interact with the island itself.

- eighth blackbird encouraged me to embrace the unexpected—to travel different routes in the storytelling, in the creation of the island’s history, of its inhabitants, and to avoid the predictable…to really dig deep and do something unique.

Each of these performances has taught me re-think what I know about art and inspiration, and they are with me every day when I write. In addition to a seemingly never-ending list of books I flip through daily—various back-issues of National Geographic featuring articles about Isle Royale (used as inspiration); a 1937 manual called Wolf and Coyote Trapping; the unbelievably inspiring/gorgeous Atlas of Remote Islands by Judith Schalansky; others—I am constantly harkening back to each performance, remembering them, and making sure that they are not forgotten. And I am reminded with every word I put down how astonishing and remarkable the performing arts are…how important they are to the production of any art.”

Each of these performances has taught me re-think what I know about art and inspiration, and they are with me every day when I write. In addition to a seemingly never-ending list of books I flip through daily—various back-issues of National Geographic featuring articles about Isle Royale (used as inspiration); a 1937 manual called Wolf and Coyote Trapping; the unbelievably inspiring/gorgeous Atlas of Remote Islands by Judith Schalansky; others—I am constantly harkening back to each performance, remembering them, and making sure that they are not forgotten. And I am reminded with every word I put down how astonishing and remarkable the performing arts are…how important they are to the production of any art.”

——

Robert James Russell is the author of two upcoming books: the collection Don’t Ask Me to Spell It Out (WhiskeyPaper Press, 2015) and the novel Mesilla (Dock Street Press, 2015). His first novel, Sea of Trees, was published in 2012. He is the founding editor of the literary journals Midwestern Gothic and CHEAP POP. You can find him online at robertjamesrussell.com and @robhollywood.”

Interested in learning more? Read our interview with Robert.

Artist Interview: Petra Haden, violinist and vocalist

Photo: Petra Haden. Photo by Steven Perilloux.

Violinist and vocalist Petra Haden has been a member of groups like The Decemberists and has contributed to recordings by Beck, Foo Fighters, and Weezer, among others. With her sisters, Petra is a member of the group the Haden Triplets and will also be familiar to UMS audiences as the daughter of the legendary jazz bassist Charlie Haden.

She performs as part of guitarist Bill Frisell’s When You Wish Upon a Star group on March 13, 2014 in Ann Arbor. The two have also created recordings together.

Greg Baise is the curator of public programs at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit. This summer, Greg spoke with Petra about working with Bill Frisell, growing up in a musical family, and her interest in the nooks and crannies of film scores.

Greg Baise: This particular UMS appearance actually encompasses two evenings and is called the Bill Frisell Americana Celebration. The first evening features Bill Frisell on guitar solo. And the second evening features you as part of When You Wish Upon a Star, a relatively new band. Can you tell me more about the band and the material you’ll be working on for the concert?

Petra Haden: We’ll play from our record, the first record [Bill and I] did together. This record came to be after I played a show in Seattle with a friend of mine, and Bill came to see that show. He was interested in what I was doing, and he called me soon after to ask if we could do a record together. I was really excited to work with him because I’m such a huge fan! We decided to record a collection of our favorite songs, a variety of music from Coldplay to Stevie Wonder to Tom Waits. “When You Wish Upon a Star” was one of the songs we worked on, and our concerts together so far have been a mixture of these songs as well as Gershwin songs.

GB: In another interview you said that Bill gets your brain. What do you mean by that?

PH: It’s something that I can’t exactly put into words. It’s so hard to describe. When we play, it’s like this language that we speak together. It’s almost like he can predict where I’m going to go next. I remember hearing him when I was younger and thinking how beautiful it was, and to finally be recording with him is a dream come true.

When I was recording with Bill for my Petra Goes to the Movies album, one of the engineers told us that we seemed like brother and sister when we worked together. So, it’s also apparent to others that we’re a good match musically.

GB: I’d love to hear about the arrangement process. Do you and Bill work together to come up with arrangements for these songs?

PH: When we started working on our first record, Bill played and I sang the melody. When we were done with the basic tracks, I added violin. I just came up with stuff on the spot. I played what I heard in my head. I came up with the string ideas for songs that I’d heard, like the songs by Stevie Wonder, and also for songs like Elliott Smith’s “Satellite,” which I’d never heard before, but Bill had played for me. That’s another way he gets my brain. He told me that I had to hear this Elliott Smith song, and that became my new favorite song. He gets my taste is in music.

GB: Listening to you as you create harmonies on the record is pretty astounding. Does it come from something that you studied, or maybe from your upbringing in a musical family?

PH: I started singing with my sisters when we were really young, probably six or seven. We used to visit my dad’s family in Springfield, Missouri. They had a radio show called “The Haden Family,” and we would sit in the living room and have fun, eat, and sing together. That’s one of the first experiences I had with singing harmonies. I remember knowing at a very young age that I loved singing harmonies, and as I grew up with my sisters, we sang just for fun.

I wasn’t really active in music in high school. But later, after I graduated, I joined a band called That Dog with my sister Rachel and another high school friend. I was involved with that band for five years. I ended up going to music school at Cal Arts (California Institute for the Arts), but just for a year, so I never really had formal music training. That’s why I tend to do everything from my head, which can be hard.

GB: Has your record with your sisters, The Haden Triplets, been in the making since your childhood?

PH: Ten years ago or so we worked with a friend who wrote a few songs for us, but we weren’t recording an album at that time—it was just for fun. Any show we played, we sang these songs, and we added [the American folk group] Carter Family songs that we’d known since we were kids. But we were all busy and didn’t pursue an album, though people often asked us when we might record.

Later, we were asked to perform at a tribute show for soul and jazz poet Gil Scott-Heron, and when percussionist Joachim Cooder found out that we were a part of it, he wanted to play drums with us. He mentioned that his dad [the guitarist Ry Cooder] was interested too, so Ry played guitar with us for that show. He’s the one who called me after to say that he was interested in producing a Haden Triplets record. I was very excited because I’m a big Ry Cooder fan. We recorded it at my sister Tanya’s house before she moved in. It’s an old, big house with tall ceilings, and it was empty, so it was a great place to record.

GB: Your most recent record is Petra Goes to the Movies. I’d like to hear about your relationship to film scores in particular.

PH: I’ve always thought about doing an A Capella “Movies” album. Since I was a kid I was obsessed with all the Superman movies. I had the vinyl for the soundtracks, and I listened to them a lot and sang the string parts in my head. That was my favorite thing about going to the movies, listening to the music. Music is what tells me the story whenever I watch a movie.

GB: In the album, you’re looking at the nooks and crannies of a soundtrack that people don’t normally look at.

PH: That’s interesting that you bring that up. Often in movies, the music that I wish was on the soundtrack doesn’t ends up on it. Like in Big Night for instance, there’s a scene that just touched me, during which the owner of the restaurant with which the brothers compete plays piano. I don’t think that’s even on the soundtrack. My friend (who engineered the album) got the video and recorded it for me so that I could hear it.

Bill plays on that album too, so it’s not entirely A Capella. He thought of the theme from Tootsie, one of my favorite movies, and that’s another example of the way that he just gets my brain.

GB: Are you planning on recording another album with Bill and the When You Wish Upon a Star group that will play in Ann Arbor, or is that to be determined?

PH: That’s to be determined. I want to record with Bill for sure, but for my next record, I’m focusing on original songs. I work really well with collaborators, so I want to find the perfect writing partner.

GB: Earlier, we talked about the way you’ve admired Bill’s work for a long time. You said that to work with him is almost like a dream project. Do you have a list of other dream projects, whether that’s material or collaboration?

PH: Lately, I’ve been listening to an album by Mark Isham called Vapor Drawings. I don’t know how to get in touch with him, but he’s someone I would want to work with. I would definitely love to work with [the composer] Steve Reich, to be one of his singers. His music is another way I learned to harmonize. I love that pulsating singing so much. My other favorite guitarist is Pat Metheny. I did have the chance to work with him when I worked on my dad’s record Rambling Boy. On that record, I sing on a song that Pat plays on, which was a dream come true.

GB: Thanks for taking the time to talk! I was really excited when I saw that you would be playing in with Bill Frisell.

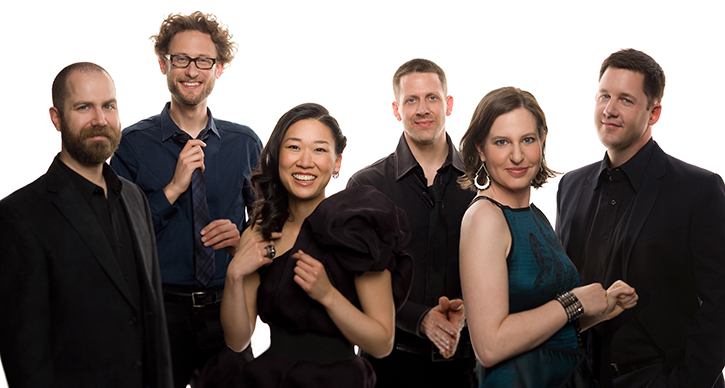

Artist Interview: Flutist Tim Munro, eighth blackbird

Eighth blackbird. Photo By Luke Ratray.

The Chicago-based ensemble eighth blackbird combines the finesse of a string quartet, the energy of a rock band, and the audacity of a storefront theater company in a dazzling performance coming to Ann Arbor’s Rackham Auditorium Saturday, January 17, 2015.

Composer and UMS Lobby contributor Garrett Schumann chatted with eighth blackbird flutist Tim Munro about the group’s unique instrumentation, theatrical flair, and magical moments onstage.

Garrett Schumann: What is eighth blackbird?

Tim Munro: Well, eighth blackbird is a chamber music ensemble specializing in music by living composers. One week we might play music that’s influenced by indie rock, the next music influenced by Balinese Gamelan, the next by an abstract piece of modern visual art.

We often memorize the music that we play, which allows us to take away stands and to have a greater intensity of communication on stage and with the audience. Sometimes that means we actually move around the stage to make manifest some of the relationships that are already inherent in the music. So a lot of the time we are trying to make this new composed music more immediately vibrant and engaging for audiences.

GS: Terrific. When you created the group in 1996 there had been ensembles with the same instrumentation as eighth blackbird for a few decades. How consciously did you guys see yourselves as emerging from that kind of ensemble tradition?

TM: To speak about the instrumentation first, eighth blackbird was sort of a put-together group. At the Oberlin conservatory, this conductor, Jim Weiss, put the group together to play more challenging repertoire, stuff that isn’t normally covered in the run of conservatory conductor. And this instrumentation seemed like the perfect kaleidoscope in everything. You have strings, you have winds, you have piano, you have percussion. You’re able to sound like you’re a string quartet, you’re able to sound like you’re a piano trio, you’re able to sound like a percussion ensemble, you’re able to sound like a full orchestra and there is just every combination possible in this instrumentation. This, I think, is why in the 20th century, it really exploded.

I think the biggest influence on eighth blackbird is an ensemble with a different instrumentation, which is the Kronos Quartet. It plays a hugely diverse range of material. Everything from the wildest, most experimental modernism to the kind of obvious, fun-loving minimalist to collaborations with popular artists and world music– and doing it in a way that made it visually engaging to audiences, but was casual enough that people could feel relaxed. So I think that was the biggest influence on eighth blackbird in its earliest stages.

GS: How do you come with this diversity of programming? What do you think it is about eighth blackbird that does that diversity so well?

TM: I think that’s something that we try very hard to represent in our programs not just because we want to check all the boxes, but because we want people to never feel bored, but to always have people engaged in a concert. The diversity of the programming just reflects the diversity of different proclivities within the ensemble. Each performer in eighth blackbird is part of the artistic direction of the collective. We are all music directors of eighth blackbird and we are all coming from very different places. We all have different music that we love and I think our programs are reflective of the enthusiasm of the group all together.

What unites all of the music that we play is something in it that is unique: a color that we haven’t heard, a particular approach to constructing a piece that we haven’t done before, a spark that inspires the piece that we haven’t encountered before… something that we can then play with theatrically. So each piece on the program in some way captures something that is unique even if they are in totally different worlds. Everything on the program gives us a little something atypical or strange.

GS: Composer and Northwestern professor Lee Hyla passed away suddenly in June 2014. What was your group’s relationship with Lee Hyla and his piece “Wave”?

TM: Well, it was such a shock for everyone in the ensemble and for the whole music community in Chicago because he was such a huge presence. He’s an original. His music has a rawness and an unvarnished-ness that feels so appropriate and typical of someone of that sort of American maverick tradition. Every member of the group has a particular fondness for one of Lee’s pieces and we all loved his music. We don’t know him well personally, I don’t think anyone in the group knew him terribly well, but we are all such huge fans and were all so excited to be able to commission the piece.

I can tell you that already in rehearsing this we’ve discussed how the piece is put together. It’s a lot of fragments, it’s a piece that’s shards of things. Beautiful, pummeling, fractal, little elements that are all in shards, sort of constructed. And when we come to the moment of rehearsal where we don’t quite know our way forward, that’s often when we will talk directly with the composer. And so whenever that happens, we have that voice in the room, but we won’t be able to do that. So I’m not sure how it will affect our performance. It’s too soon for us to say.

Maybe because this is the only piece of his that we’ll ever be performing posthumously, there may be something different about the way that we and future groups approach it. It’s a piece that’s actually in its kaleidoscopic-ness begins with this vast, incredibly slow, incredibly astute music, and the last voice is the cello who has this upward gesture that almost feels like a question mark. I don’t know if one should put any emphasis on that, but for us, this performance asks us to think about those things.

Interested in learning more? Check out other interviews by Garrett Schumann.

UMS Playlist: A Touch of Minimalism

This post is a part of a series of playlists curated by artists, UMS Staff, and community. Check out more music here.

Dawn of Midi perform at Trinosophes in Detroit on January 31, 2015. Photo by Falkwyn de Goyeneche.

Minimalism can be extraordinarily beautiful. I’ve always been a believer of “less is more.” In the right hands, repetition, simplicity, and homogeneous textures of sound can envelop the listener in deeply meaningful and even spiritual ways.

In the playlist below, I’ve attempted to offer a sampling of minimalist techniques in a cross-section of genre and style, from pioneering tape experiments by Steve Reich (“It’s Gonna Rain,” ca. 1965) to minimalist 1990s electronica from the UK’s Richard D. James (aka Aphex Twin) and the Manchester duo Autechre (selected from their seminal 1995 LP Tri Repetae) to Dawn of Midi, a group with a mesmerizing, “electro-acoustic” sound that will perform at Trinosophes on January 31, 2015.

I have also included some surprises: Jason Moran and The Bandwagon’s cover of American-born innovator Conlon Nancarrow (who composed “Study No. 6” for player piano) and downtown New York experimental post-disco songwriter, cellist, and composer Arthur Russell (who died in 1992 at the age of 40 in relative obscurity).

This playlist represents merely a snapshot of some of my favorite minimalist moments. Hopefully it will encourage and inspire a deeper personal journey of discovery.

Please note: These fascinating (and intricate) soundscapes are best experienced on headphones.

What did you think about this playlist? Share your thoughts or song suggestions in the comments below.

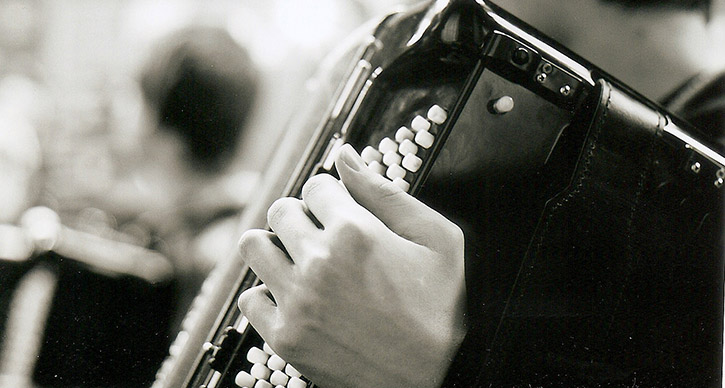

A [brief] UMS History Presentation: The Accordion

We can’t wait until accordions of all sorts take the stage for The Big Squeeze: An Accordion Festival.

In the meantime, study up with this infographic of a brief history of accordion, accordions around the world, and accordions in popular culture.

Are you an accordion admirer or an accordion player? Share your best accordion stories and family history below.

Listening Guide in Samples: Bob James

Jazz keyboardist and composer Bob James is also one of the most sampled musicians in the history of hip-hop. He’ll perform in Ann Arbor on November 15, 2014. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Hip-hop appropriated the soul and rhythms of many genres of music and cultures, and hip-hop is contagious. It’s a force that blasted its way out of the inner city into bedrooms and basements everywhere.

Hip-hop is rooted in making something out of nothing, using the few tools at the musicians’ disposal to create art that paints a picture of a part of society largely ignored. Before hip-hop’s inception, jazz, blues, soul music, and rock-n-roll were the prior generations’ outlets for creating a rich counter-culture that would influence the communities of the future. Hip-hop was an explosive melting pot of all of these cultures, and so it wasn’t shocking that many of musicians who had begun to experience success in earlier decades enjoyed a new life through sampling in hip-hop. One such example is jazz pianist Bob James.

From One by Bob James:

In the 70s, James was arranging and producing with many fellow jazz artists, including on saxophonist Grover Washington Jr.’s classic albums, while also putting out his own solo albums like One or Two. These albums and his other music would become the foundation of many hip-hop staples of the 80s and 90s. The worlds Bob James would create during this time, while working with musicians such as saxophonist Dave Sanborn, singer Hubert Laws, and drummer Idris Muhammad, to name a few, were filled with a massive soul that mixed dreams of fantastical lands with the struggles of reality. The culture of hip-hop would reinvent that feeling in the following generations.

“Angela” by Bob James:

Bob James, who is an alumnus University of Michigan, would go on to success in the jazz world, but his music really entered American living rooms everywhere when he penned “Angela,” the theme music for the popular TV show Taxi that aired from 1978 to 1983 and spawned a slew of well-known actors and comedians. Later on, “Angela” would be sampled by Bay Area hip-hop group Souls Of Mischief for their song “Cab Fare”, which was slated for their 1995 full length album No Man’s Land but was unfortunately axed because they could not get the sample legally cleared (it’s out there now, go look for it!).

The works of Bob James have been sampled many times within hip-hop as well as by R&B and drum-n-bass artists, but there are two specific songs that have been used more than anything else and have lead to some well-known hip-hop records.

“Nautilus” by Bob James, sampled:

From the Bob James’ 1974 album One, the closing track titled “Nautilus” has given us great hip-hop songs over the years. As we enter the first few seconds of “Nautilus,” we hear the haunting sounds would be sampled by the legendary producer DJ Premier for Jeru The Damaja’s “My Mind Spray” from his 1994 album The Sun Rises In The East. Then, a few seconds later, right as the song really kicks in, is the sample that the Wu Tang Clan’s The RZA used for fellow group-mate Ghostface Killah’s “Daytona 500” from his 1996 solo album Ironman. “Nautilus” has been sampled in dozens of other songs including by Eric B. & Rakim (“Let the Rhythm Hit ‘Em”) and Soul II Soul (“Jazzie’s Groove”), but it’s the segment about two-thirds into the composition, during another ghostly breakdown, that Run D.M.C. would pick up and turn into the main infectious sample for their renowned record “Beats to the Rhyme.”

“Take Me to the Mardi Gras” by Bob James, sampled:

While the sampling of “Nautilus” spawned many hip-hop tracks, James’s 1975 album Two and the song “Take Me to the Mardi Gras” resulted in some of the most legendary tracks. The bells and drum breaks from “Mardi Gras” would be most famously sampled by hip-hop legends like Run D.M.C. (“Peter Piper”), LL Cool J (“Rock The Bells”), and the Beastie Boys (“Hold It Now, Hit It”). “Take Me to the Mardi Gras” isn’t just the foundation for these celebrated songs, it’s also the backdrop for the sound of late 80s hip-hop culture. Those bells and drums from “Mardi Gras” create the vision of inner city kids break-dancing on the sidewalks, spitting rhymes on the corner, or tagging graffiti on a wall downtown.

Bob James has continued to produce and arrange music as a highly successful solo jazz artist and along with his legendary band Four Play, but his work from the 1970s as a producer, arranger, and as solo artist has left a lasting effect on in the hip-hop world, an effect that will continue for generations of emcees and producers to come.

Interested in learning more? Check out Kelly Frazier’s listening guide to pianist Ahmad Jahmal, who’s also been sampled into the hearts of hip-hop.

Artist Spotlight: Why We Love Accordion, and You Should, Too

Editor’s note: UMS presents The Big Squeeze, an evening of accordion music of all sorts, at Hill Auditorium on November 1, 2014. Accordionist Julien Labro is not only part of the program but also a co-curator for the event. Read about what he loves about the accordion (and why you should too!) below.

Photo: Up close with one of the Accordion Virtuosi of Russia, who’ll perform as part of The Big Squeeze, an evening of accordion music in Hill Auditorium. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Whether it is a boozy uncle insisting on playing it at family parties, or the distant nerdy cousin secluded in his bedroom, or a friend-of-a-friend, most of you know someone who has played the accordion. Yes, you read that right!

Indeed the theory of six degrees of separation will link you with the widely popular and multi-cultural accordion.

The accordion has always been a huge part of popular culture and is frequently the centerpiece of the folk music of that ethnicity. Whether you are Irish, French, Italian, German, Polish, Russian, Hungarian, Colombian, Brazilian, Argentinean, Dominican, Mexican, Jewish, Egyptian, Algerian, Lebanese, Persian, Indian, or Chinese, the accordion and its relative instruments dominate the musical landscape of that traditional music.

That’s why we’re so excited about The Big Squeeze, an evening during which we’ll explore the versatility of the accordion by travelling through different musical styles and genres representing various countries.

An extensive array of diverse accordions and their relatives will appear throughout the performance: the piano accordion, the bayan, the chromatic button accordion, the bandoneón, the accordina, the diatonic accordion, and the Anglo-concertina.

Accordion: A Brief History

Alexander Sevastian, who’ll perform as part of The Big Squeeze, plays Bach.

All of these instruments function under the same sonic principle: an airflow streaming across a free vibrating reed that resonates a tone based on its length. The first instrument known to have used this principle can be traced back to 3000 BCE in China with the scheng, an instrument made out of bamboo pipes set in a small wind-chamber into which a musician blows through a mouthpiece. Suspected to have journeyed to Europe during the 13th century, the scheng hardly faced any major adaptations until the Industrial Revolution. A closer predecessor of the modern accordion is arguably credited to Cyrill Damian, an Austrian instrument maker who patented the name in 1829. Naturally, the instrument wasn’t as developed as the ones you’ll hear at The Big Squeeze, but offered the general concept of the bellows sandwiched between two manuals.

At the turn of the 20th century, accordion manufacturers realized the extensive presence of the piano in American homes and salons. Consequently, they decided to seduce and target piano players with the accordion by offering piano keys in lieu of the traditional buttons on either side. Its convenient portability and comparative affordability contributed a great deal to its commercial success, which is the reason why the majority of the population familiar with the accordion recognizes it with a piano keyboard on its right side. However, the rest of the world adopted the initial concept of an all-button instrument as the primary blueprint for the accordion.

The Big Squeeze: An Accordion for Every Taste

In Russia, the bayan, a high-tech button accordion, became one of the centerpieces of traditional folk music. Its gigantic typewriter appearance allows for limitless technical dexterity and its distinctive sound emulates that of a pipe organ. The Accordion Virtuosi of Russia will perform exquisite arrangements of popular Russian folk songs and some staples of classical music that will feature both piano accordions and bayans. Alexander Sevastian, who also hails from Russia, will demonstrate some of the finest technical dexterity and subtleties performed on bayan.

Julien Labro performs with Spektral Quartet

Similar to the bayan in shape and size, I will perform on the chromatic button accordion, whose concept is close to its Russian relative, but its keyboard layout and timbre very different. The chromatic button accordion is the most popular type of accordion found in Europe. Also European in its conception, I will introduce you to a German instrument conceived to replace pipe organs in underprivileged parishes, the bandoneón. Invented and named after Heinrich Band, the bandoneón is much smaller in shape than its cousin, the accordion. Although the principle of the vibrating free reed remains, you will notice a deeper, more mournful, and melancholic sound produced by this instrument. These sonic qualities staged the instrument to become the soul of the Argentinean popular music: the tango.

Additionally, I will present the accordina, which could be described as a hybrid between a harmonica and a chromatic button accordion. The accordina, invented by André Borel, can be traced back to the early 1930s in France; it borrows its free reeds and its button keyboard from the chromatic button accordion and inherits the harmonica’s breathy quality which it expresses through a mouthpiece.

John Williams will transport us to Ireland and remind us that we don’t need to be waiting for March 17 to sip a room-temperature Guinness. He’ll perform on two different types of accordion that are primary instruments found in Irish traditional music: the diatonic accordion and the Anglo-concertina. The diatonic accordion is small and offers two or three rows of buttons. Each row is tuned to a specific tonality and only offers notes that belong to that tonal center. Most of the diatonic instruments are generally in only one or two keys, so players tend to own several instruments in order to perform throughout all key signatures. It is also interesting to note that each button on these types of instruments produce different pitches according to the bellows’ direction. Hexagonally shaped, the Anglo-concertina is one of the smallest members of the accordion family. Like the diatonic accordion, one single button offers two notes depending on the bellowing. Its timbre is unlike any of its relatives, more nasal and enigmatic; it fits dreamily in some of the classic Irish ballads.

On behalf of the entire UMS team, I sincerely hope that you join us for this program which reveals some of the existing types of diverse accordions found throughout various musical styles and cultures. Hopefully the evening’s program will shed light on some of the musical versatility that the instrument has to offer beyond what you may have experienced from the boozy uncle and the distant, nerdy, secluded cousin.

And if by time you read this, you haven’t found six degrees of separation between you and someone you know who has played the accordion, a simple Facebook “friend request” to any one of us will do the trick.

Interested in more? We asked Julien Labro what he’s been listening to lately. Listen along to his playlist.

Behind the Scenes with Accordionist Julien Labro

This post is a part of a series of playlists curated by artists, UMS Staff, and community. Check out more music here.

Accordionist Julien Labro performs alongside with other artists as part of Big Squeeze: An Accordion Summit on November 1, 2014 in Hill Auditorium. Photo by Anna Webber.

Accordion virtuoso Julien Labro (of Hot Club of Detroit) performs with Chicago-based contemporary classical Spektral Quartet, the Accordion Virtuosi of Russia, the Irish Duo, and accordionist Alexander Sevastian as part of the Big Squeeze, an evening of accordion music on November 1, 2014 at Hill Auditorium.

We asked Julien to share a few of his favorite tunes with us, and to tell us a bit about what he loves about them. Check out his selections and listen along below.

1. Jeff Ballard Trio with Lionel Loueke & Miguel Zenón – “Beat Street” from Time’s Tales

Three of my favorite musicians getting together. Love the vibe and instrumentation, and the different musical directions achieved. Check out “Hanging Tree” from the same album for a total different vibe from the track I selected.

2. John Coates Jr. – “Yesterday” from The Jazz Piano of John Coates, Jr.

Just found out about this pianist a few days ago. Keith Jarrett played drums in Coates’s piano trio for some time, so it’s interesting to hear some of Keith Jarrett’s early musical inspiration.

3. Stromae – “Formidable” from Racine Carrée

I discovered this Belgian artist while watching a French talk show some time ago and was very impressed with his performance and demeanor. It’s currently back in my rotation, especially this track which is the one I heard that day.

4. Jimmy Smith – “Cat in a Tree” from Peter & the Wolf And the Incredible Jimmy Smith

I’ve always been a fan of Jimmy Smith, and this song features him with the Oliver Nelson’s big band. They collaborated on a handful of albums but the choice of material is a bit different from their previous work since the album based on the themes from Prokofiev’s Peter & the Wolf.

5. Jay-Z & Kanye West – “Lift Off” from Watch The Throne

I listen to all sorts of music and hip-hop is no exception. The whole album is awesome, and this particular track may be more “poppish” than hip-hop, perhaps due to Beyoncé’s presence. Regardless of what we want to label it stylistically, I really dig the hook and the track.

6. Now vs Now – “Future Favela” from Earth Analog

I’ve been into this band for a couple years now. Jason Lindner is an awesome pianist and keyboardist, super creative, and Mark Guiliana is also one my favorite drummers.

7. Charlie Haden – “Song For Che” from Liberation Music Orchestra

Charlie Haden, a jazz giant, has left us recently, so I’m listening to some of my favorite albums, like this one, as well as unfamiliar ones as a personal homage to this bass legend. I love this entire album and this Haden’s composition always resonated with me.

8. Jack Bruce – “Sam Enchanted Dick Medley” from Things We Like

Just got hipped to this reissue. This is Jack Bruce (Cream’s bass player) playing upright bass in a somewhat free jazz setting. Very interesting and cool album, noteworthy is the presence of young guitarist John McLaughlin playing here right before joining Tony Williams’ band Lifetime.

9. Clark Terry – “Brother Terry” from Color Changes

Listened to this for the first time a couple weeks ago while in Lebanon riding in the car with the trumpet player from the Lebanese Philharmonic. I flipped out about how good and fresh this was despite being recorded in 1960, the arrangements and instrumentation and playing sound so hip, amazing! It also reaffirmed for me that good music is timeless and appreciated all across the world.

10. Chico Buarque – “Funeral de um Lavrador” from Per un Pugno di Samba

Big fan of Brazilian music and of course of the great singer songwriter Chico Buarque. This is a great album recorded in 1970 and arranged by Ennio Morricone!

11. Maurice Ravel – Second Movement (Assez vif. Très rythmé) of String Quartet in F Major

I always like to explore composers that I know well time and time again because there are always new things to discover and intricate details I’ve missed. I oftentimes arrange and write for strings, and I’m always in awe of Ravel’s chops as an orchestrator.

12. Hossein Alizadeh & Djivan Gaspariyan – “Mama” from Endless Vision

Just discovered Hossein Alizadeh through an Iranian friend, and I feel in love with his music. On this album, he’s joined by duduk master Djivan Gaspariyan. This music and this track in particular transports me to visual and emotional places…amazing!

13) Laura Mvula – “Father Father” from Sing to the Moon

Love her vocal chops and style. The live solo version of this song is even better than this studio cut….YouTube it, you won’t be disappointed I promise.

14) Richard Bona – “Dina Lam” from Munia

I first heard this song on Bobby McFerrin’s Live in Montreal DVD. Richard Bona, one of the guests stars, joins for a duo performance with snippets of this song, which also made me dig up this album.

15) Brian Blade & the Fellowship Band – “Ark.La.Tex” from Landmarks

I’m a big fan of Brian Blade. I’ve seen him perform in many musical settings and with many bandleaders (Wayne Shorter, Chick Corea, Joshua Redman, Daniel Lanois to name a few). I enjoy his songwriting and I’ve always love his Fellowship Band especially since it’s musically different from the usual setting I get to hear him in.

What did you think about this playlist? Share your thoughts or song suggestions in the comments below.

A [brief] UMS History Presentation: The Guitar

As we get ready to welcome the Los Angeles Guitar Quartet to the Michigan Theater on April 10, 2014, we’re taking a look back to see just how far the guitar has come.

UMS Playlist: “NEW” Music by UMS Associate Programming Manager Liz Stover

This post is a part of a series of playlists curated by UMS staff, artists, and community. Check out more music here.

Photo: Colin Stetson will perform in Ann Arbor January 15-16, 2014. Photo by Keith Klenowski.

We’re in the middle of a really exciting but possibly confusing time in music. Exciting because tons of new music is being created and performed, but confusing because people aren’t entirely sure what to call it.

An emerging young generation of artists and composers who have influences in both classical and popular music are creating work that doesn’t necessarily live within any pre-existing genres that audiences and critics are familiar with. Some of it might sound like a new kind of “classical”, or instrumental music. Some of it sounds like pop.

All genres aside, I’ve discovered lots of great music in recent years through my own background in playing violin and classical chamber music, as well as through my love of rock, popular, and indie music. What’s really exciting is how much collaboration happens between so many of these artists. No one works entirely alone — the artists compose and commission music for each other, or play on each other’s records or tours. You may remember last season’s concert by Gabriel Kahane and the sextet yMusic, whose members are all classically-trained musicians but also play regularly with indie rock stars such as Sufjan Stevens, Bon Iver, and The National.

I’m looking forward to Colin Stetson’s performance this January. A classically trained saxophonist (as well as Ann Arbor-ite and graduate of the University of Michigan), he’s worked with dozens of artists, including Tom Waits, Feist, Laurie Anderson, Lou Reed, David Byrne, LCD Soundsystem, and Angélique Kidjo, among others. I also loved UMS’s presentation of Brooklyn Rider in November, a string quartet known for exciting collaborations who performed a concert to showcase their recent work with banjo player Bela Fleck. Want to hear more? Check out New Amsterdam Records, a Brooklyn-based record label that produces many records and concerts by these artists and more.

What did you think about this playlist? Share your thoughts or song suggestions in the comments below.

Interviews with Uncommon Virtuosos: Robert Alexander

Photo: Robert Alexander. Photo by Kärt Tomberg.

Robert Alexander is a sonification specialist working with the Solar and Heliospheric Research Group at the University of Michigan, where he is pursuing a PhD in Design Science. He is also collaborating with scientists at NASA Goddard, and using sonification to investigate the sun and the solar winds.

We met Robert this fall and got to talking about “uncommon virtuosos” – those who master an instrument or genre in unexpected ways, whether Colin Stetson on the baritone saxophone this January or Chris Thile on the mandolin last October.

We sat down with Robert to talk to him about the nuts and bolts of sonification, his new work in sonifying solar wind and DNA, and whether he’d consider the sounds of the sun improvisation.

Nisreen Salka: How did you get into sonification?

Robert Alexander: My background is in music composition and interface design as the focus of my undergraduate and master’s studies, and I transitioned more into using those disciplines towards scientific investigations more recently. I came to work with sonification specifically when I was approached by Thomas Zurbuchen, who is the leader of Solar Heliospheric Research Group (SHRG), and they had this crazy idea of hey, let’s take our data, turn it into sound, and see if we can learn anything new.

NS: Could you describe sonification for the laymen among us? How does that relate to your previous experience in music composition?

RA: Sonification is the use of non-speech audio to convey information. And the idea is that rather than visualizing data and creating a graph or something of that nature, we can instead create an auditory graph. So if we have something like a data value that’s constantly rising, rather than displaying that as a line that constantly goes up, we can have a sound that constantly goes up in pitch.

NS: In your mini documentary about the project with Solar and Heliospheric Research Group (SHRG), you talk about including a drum beat and an alto voice to better personify the satellite data. How did you figure out which musical elements would work?

RA: Well, it’s a process where I first begin by getting as close to the data and the underlying science as possible because I want to let the data to speak for itself, and try to find the natural voice of the data. Once I get a sense for what the data are actually saying and what the data parameters are actually telling me, then I can start to think a little bit about, okay, how could this unfold musically?

And that’s largely a process of trying to work with informed intuition. I’m trying to think about what sort of knowledge the listener is going to bring to the listening process, and I try to work with sounds that might be intuitive.

NS: Sonification seems like a medium for improvisation, but there’s a lot of structural overlay. Do you, as a composer, consider your work improvisational?

RA: I think there’s very much an improvisational element, and you’re going to find that in scientific research even though you may expect it less. We’re talking about an interaction in which we feel so connected with our instruments that we are able to go from an idea to an expression of that idea in a very short amount of time. And one of my goals has been to take this kind of immediacy and try to infuse the sciences with that immediate feedback.

NS: It sounds like sonification really a combination of two disciplines. How did this fusion happen for you? What about this process attracts you both as a scientist and an artist?

RA: As a composer, I’ve always used music to explore my own psyche and the human condition as a form of self-expression. I think the largest shift that took place in my thinking as a composer was this kind of shift from thinking about music and asking, “What do I want to express?” to instead thinking, “How could I use these compositional tools to allow something like the sun to express itself?” I saw this as an opportunity to take something I really love and channel that through a rich learning process.

When science or music happen at a very high level, they are both infused with creativity. And I think the idea of that separation between art and science is more of a modern invention. When I think about these two disciplines, I tend to think about the things that bring them together. A lot of science has sprung forward through different types of intuitive leaps, and I think that it’s this place of intuition that plays into the process of being a creative professional or of being a scientific researcher. That’s the core of a lot of the work that I do.

NS: How do you think people receive what you do? What is their perception when they see the final result?

RA: I think many people initially think, well that is “cool.” But for me, the question isn’t, “How do we make something cool?” The question is “How do we learn something new?” In the moment when we are able to uncover something in a data set with our ears, it’s still cool. But to actually learn something, then it also becomes powerful.

In all of my work, I try to pair the music and the data such that I’m providing knowledge as to how the musical form is drawn directly from the underlying data set. I like to encourage the listener then to simultaneously absorb the music and to investigate the underlying science because that’s when sonification really becomes powerful, when it can fuel the learning process. It takes the abstract and the esoteric and makes it more approachable.

NS: We know that one of your newer projects is the sonification of DNA. How does that relate to your previous work? What about it is new and what about it is similar to what you have done in the past?

RA: This project was an opportunity to take everything I have learned in the space sciences and to apply that to a new discipline in which I had limited prior knowledge. Just like working with solar wind data, we were working with incredibly large amounts of information. Millions of data points could potentially be passing by the ear over the course of a minute.

We were successful in creating an auditory translation, where you can hear where the transcription process starts and ends, and you can hear the structure of the gene. It was really fascinating to have a sense for how this would unfold temporally rather than just seeing it as a sequence of numbers or letters.

A lot of genetic research has also utilized spectral analysis to analyze repeated elements in DNA. And turns out if we take that raw data and turn it into sound, we can hear those repeated elements. Sonification could potentially allow us to hear some of the subtle details in these structures.

NS: Is there anything else we haven’t covered that you want to add about your projects?

RA: There are still a lot of mysteries when it comes to solar science. And we are looking at sonification as a way to gain new insights. Working at NASA Goddard alongside several research scientists there, we actually uncovered quite a variety of new features with our ears that we’re now investigating through traditional research methods.

And so for me, it’s a really exciting time. We came into the project wondering if we’d find something new, and now we’re at the point where I can say that we have been successful in uncovering new science through the process of data sonification, and we’re continuing to discover new things.

Learn more about Robert’s work here. Questions or thoughts? Leave them in the comments below.

Artist Interview: Colin Stetson

Photo: Colin Stetson, who performs in Ann Arbor on April 14, 2018. Photo by Scott Irvine.

In January 2014, saxophonist Colin Stetson performed in Ann Arbor as part of a special week of Renegade performances also featuring performances by the Kronos Quartet. We’re looking back on our chat with Colin to get ready for his return to UMS on April 14, 2018 in Colin Stetson: Sorrow: A Reimagining of Górecki’s Third Symphony.

UMS: Your performances are a part of a “renegade” theme in our season, through which we explore artists and composers who “break the rules” in their own time. How do you feel about the term “renegade”?

Colin Stetson: I don’t think I particularly feel much about it actually. I don’t think about myself or this music in those terms at all.

UMS: How do you think about it?

CS: Well, I think that that terminology kind of implies a certain comparison between inspiration and performative processes of your music to other people’s processes and to the greater whole of music making, and I really don’t function that way when I’m making this music.

If there is any amount of boundary pushing or ground breaking, it’s really more of personal journey and a personal set of goals that I kind of outline for myself. And I’m constantly looking for new ones, and then establishing the pursuit of said goals. So it’s much more of an intimate and insular process in my case.

UMS: Are there artists who take a similar approach from whom you take inspiration?

CS: There are artists really across the board from different genres and different eras that I take inspiration from but not necessarily in a process sort of way. I don’t really know that I’ve ever specifically inquired into someone else’s process and then been inspired by that, so much as I am inspired by the finished product, and what that does and their intention, the intention that’s successful, housed in the music that they created, and then transmitted to the listener. So that’s I think more so where I would consciously cite inspiration or influence.

UMS: You have roots in Ann Arbor. Is coming to Ann Arbor special for you?

CS: Of course. It’s where I grew up. So, all the places in Ann Arbor have a little more historical significance for me, in terms of what I’ve done in them. When we grew up, I was playing in the bars throughout campus all through my teens, and then an enormous amount when I was in college. All of those places have a greater lineage for story for me, some much more so than others.

UMS: Last time you performed in Ann Arbor, you played the Blind Pig, and this time you’ll be performing in more of a theater space. Does the venue change your approach to the performance?

CS: Very much so. One of the things that I’ve been really lucky with in my career is having this extremely disparate selection of venues that I play at. Throughout a tour I can be playing at jazz venues and little clubs, rock venues, some very large, and churches, proper theaters.

So there’s been an enormous amount of different venues, and they’re all very specific in how they accept sounds and how they reflect sound and how they treat an audience, how an audience feels in that space, whether they feel attentive and intimate or exposed, or whether it’s a loud space where there is much more extraneous noise.

A rock club doesn’t necessarily feel better or worse, but there are just differences. There I can rely more on the sheer mass of sound because that’s kind of the domain of the rock club, is moving a lot of air, moving a lot of sound, and filling up in that way. And in a theater, where the convention is more along the lines of sitting very quietly, shunning all extraneous noise, exposing all the minutia, I’m really able to exploit that.

UMS: Kronos Quartet is also a part of our renegade week of performances. Do you like that group’s work? What makes that work stand out?

CS: They were hugely formative for me and my friends when we were coming up. We met in the university, and we were training largely classically, and sometimes academia tends to compartmentalize to such a degree when it comes to genre and idiom, so you know, here is the improvising group, and here is the classical ensemble, and here is the jazz ensemble, and everything is really toeing the line.

But what we were really interested in was just music that came very intuitively to us because we were listening to improvised music, because we were listening to soul and R&B, because we were listening to metal, the music that came out of us tended to be an amalgam of all of that, a much more organic mixture.

And here was a group, Kronos Quartet, who was doing just that. They were forging a path that was not pre-established or genre-specific, and doing it in such an incredible way, they’re such brilliant artists and technicians. It was a great example for young players, and continues to be, musically, for me and my friends now.

Interested in learning more? Check out our Colin Stetson listening guide “Wild Forces at Play.”

Wild Forces at Play

Photo: Colin Stetson, who performs in Ann Arbor on April, 18, 2018. Photo by Scott Irvine.

It begins with a deep breath, followed by resonant palpitations underlying the emergence of whistles, screeches, honks, and warbles that are progressively arranged and hoisted into a creature of dazzling, dizzying complexity. At each moment in this evolution of sound—highlighted by its spiraling melody and blistering ostinati—collapse feels imminent, and chaos, inevitable.

This specimen, “And It Thought to Escape,” exemplifies the unpredictable long-form sonic structures created by the saxophonist Colin Stetson. “And It Thought to Escape” clocks in at over eight minutes, and yet this song seems to fly by, as do others by Stetson, whose gradual and fitful development of melody is surprising and mesmerizing.

“And It Thought to Escape”

A sweat-flecked, lung-wringing feat

Avant-garde, jazz, and indie music scenes are frothing over with innovative and talented musicians whose songs explore dissonance, repetition, and non-traditional forms, especially through the use of digital effects and loops. What distinguishes Stetson from the masses is his virtuoso technique on saxophone—including alto, tenor, baritone, and the formidable bass—clarinet, and French horn.

He’s a master of circular breathing—the method of using stored air in the cheeks to continue playing while inhaling through the nose, in order to produce a seamless sound—which allows him to perform and record his long solos live and in a single take, without overdubbing or loops. Stetson has honed his circular breathing for twenty years; he learned it at age fifteen, from a music instructor who told Stetson that the technique would help him interpret classical string music without having to pause and take breaths.

While the method is somewhat tricky to learn, its use isn’t rare among wind instrumentalists. Stetson’s use of circular breathing is remarkable, though, given the extreme intensity and duration of his songs, such as the leviathan “To See More Light,” a fifteen minute song from his latest solo album, New History Warfare, Volume 3: To See More Light. The song opens with disconnected blares of the saxophone and passes through tonal states of frenzy, delirium, and grim weariness, before arriving at a warm and vaulted unity.

There’s a raw physicality to Stetson’s music. It howls. It heaves and churns. Watch Stetson perform live and a song becomes more than a song but a sweat-flecked, lung-wringing feat of musicianship requiring tremendous stamina. In many songs we hear his breathing: it’s a faint breeze in “To See More Light,” and a steady gust filling the interstices between lightning-fast synth-sounding trills in “Nobu Take” on New History Warfare, Volume 1. “This all originates in breath. It’s all tied to breath, it’s all tied to my body,” said Stetson about his music in a 2011 interview with Jian Ghomeshi, host of the CBC talk program Q. Stetson discussed his reason for avoiding digital gadgetry, explaining that his music, from the moment of its composition, is inexplicably bound with the physical process of its creation. “The parameters that I had set up for myself, initially, [were] just that everything that could be captured in the moment, physically, by me with the instrument, was fair game, but no additions, no effects, no electronics or anything like that.”

“Nobu Take”

From digital to otherworldly

It’s clear that Stetson’s parameters have been more liberating than limiting. He has undertaken a serious exploration into the sonic-making capabilities of the saxophone. Not only is he adept at creating densely layered music, but he does so with a variety of sounds, rhythms, and textures not commonly found in solo saxophone music. The music is deeply human, but its sound can range from digital to otherworldly. In “Tiger Tiger Crane” on New History of Warfare, Volume 1, Stetson uses the saxophone keys to tap out a ghostly hip-hop rhythm. There are trenchant, wordless vocals that frequently surface out of fuzz and static on the albums New History Warfare, Volume 2: Judges and To See More Light.

While recording the songs for Judges, Stetson used up to twenty-four microphones—in the studio and attached to his sax and himself, including a dog-collar microphone over his vocal chords—in order to capture the full spectrum of sounds he was producing. The song “Judges” is an excellent example of Stetson’s polyphonic abilities: he lays down an irresistible rhythm and bass line and then adds a lacerating wail as fierce as rock music’s most scorched-earth vocals. In the first video below, Stetson performs “Awake on Foreign Shores” and “Judges.” In the second video, he dissects the different sounds that comprise “Judges.”

On “A Takeaway Show”

Colin Stetson breaks down “Judges”

Stetson is an Ann Arbor native who studied at the University of Michigan. Older jazz lovers might remember him as a member of the popular avant-garde jazz-funk group Transmission, which performed around Ann Arbor and Detroit during the latter half of the ‘90s. Younger music fans are sure to recognize the groups and artists he’s performed, recorded, or toured with, including the Arcade Fire, Bon Iver, TV on the Radio, Tom Waits, David Byrne, The National, Laurie Anderson, Antibalas, Lou Reed, among many others. All music enthusiasts are sure to find something to enjoy in his solo work, which he began focusing on in 2003 while living in New York City.

In 2008, Stetson released his debut solo album, New History Warfare, Volume 1, followed by 2011’s Judges and 2013’s To See More Light. Each album in this conceptual trilogy is unique; when considered as a whole, they reveal an emotional, physical, and mental deepening of Stetson’s craft. Each album balances long, epic songs with short pieces that span just a minute or two in length and which serve as heightened meditations on a discrete phrase or rhythm. There is some over-dubbing of guest vocals: Laurie Anderson supplies ominous spoken word pieces to Judges, and Bon Iver’s Justin Vernon lends his distinctive, soaring voice to songs on To See More Light, including “Who The Waves Are Roaring For.”

“Who The Waves Are Roaring For”

I’ve resisted labeling Stetson’s music as one genre or the other, because it’s something that Stetson refuses to do. And for good reason: his musical aesthetic, while at one time rooted in free jazz, is so healthy and permeable that it has allowed many different styles and genres to enrich it, without being stunted or saturated by one in particular. There’s jazz, pop, hip-hop, metal, post-rock, drone, minimalism, folk, electronic, and more. Whether your record collection contains Evan Parker or Sonic Youth, it’s easy to find something to enjoy in Stetson’s impressive and groundbreaking body of solo saxophone works. To return to Jian Ghomeshi’s interview with Stetson, Ghomeshi at one point asked Stetson to comment on the fact that his music doesn’t resemble most saxophone music, that Stetson was “creating music that isn’t even identifiable as sax.”

“It will be identifiable as sax,” Stetson responded. “Everything that I use is stuff that has really been utilized for decades in the free jazz and free improvisation traditions. I’m just re-contextualizing. I’m telling my own story with it.”

In Studio Q:

Artist Interview: Kronos Quartet’s David Harrington

Photo: Kronos Quartet, with David Harrington on left. Photo by Jay Blakesberg.

The Kronos Quartet performs two different programs in Ann Arbor on January 17-18 2014, as part of a special week of “renegade” performances also featuring saxophonist Colin Stetson.

We called up Kronos Quartet founder and violinist David Harrington to chat about his take on renegade music, how George Crumb’s epic Black Angels (which will be performed in Ann Arbor) inspired him to found the Quartet, and his take on artists who re-define instruments as Colin Stetson does.

UMS: Your performances in January are a part of a series of renegade performances this season, as part of which we’re presenting many different artists who break the rules in their own time. How do you feel about that term “renegade”?

David Harrington: Well I like it! Suits me just fine! I’ve always thought of the string quartet as offering composers, performers, and audiences a sonic glimpse into the inner world that we all participate in, and when someone does that, when they listen to their own voice, their inner voice, dramatic things happen because it’s not necessarily the voice that the society listens to and that conventional rules conform to. And so I think that the term renegade fits our music perfectly.

UMS: Is there anything about your history that strikes you as particularly “renegade”?

Since I was a little kid I felt that the art form as a whole needed a little kick in the butt. When I was growing up and I’d go to string quartet concerts—I always sat in the front row, by the way, it’s a great place to sit—

UMS: Why do you say that?

DH: Because you can see the action, you can hear the stringiness of the sound, you can see the rosin fly, and that tactility, that horse hair meets the string, the flesh meets the wood…I love that aspect of what we do. And when I go to a concert I like to be sure I can feel as much of that as possible.

But when I was growing up and going to string quartet concerts, I was always the youngest one at the show. Always. And usually concerts started with Haydn or Mozart and then usually there’d be an intermission and then Beethoven. That’s what the art form was to the general public at that point.

The Vietnam War was raging as well, and so how does one find a voice that feels real? And in August of 1973, on the radio one night, I heard Black Angels by George Crumb. And for a moment the world made sense. And I didn’t have really any choice but I had to start a group in order to play that piece.

UMS: We actually had the chance to speak with George Crumb about Black Angels and how that piece came together.

DH: Well, it was premiered at the University of Michigan.

UMS: Yes, it was! And he actually talked a bit about the way Kronos Quartet performs Black Angels, with theatricality.

I can’t imagine what it would have been like for the Stanley Quartet to get the manuscript of that piece. I wish I could have been in the room and seen their faces when they saw that.

UMS: Funnily enough, George also spoke a bit a bit how he was actually a conductor for this piece.

DH: Yes I know! He conducted the premiere.

UMS: How did you decide to approach it the way that you do?

Well first of all, I thought about the effect that the piece had on me personally. It changed my whole life. And so for me, every time we’ve ever played it I’ve been aware of its power. And I’ve hoped, all of us in Kronos have hoped to transmit that kind of visceral potentially life-altering experience.

We’ve probably played it close to 200 times, in all kinds of settings from concert halls, churches, basketball arenas, opera houses. It’s been in a lot of places.

And it took sixteen years for Kronos to record Black Angels. So we did not record it until 1989. And I’ll tell you the reason. I felt the group needed to learn more about the recording studio and how to make the sound kind of jump off the record or the CD right into the imagination of the listener.

But even more importantly, I knew that our performance of Black Angels had to be the first track on a recording. So there’s no way you could avoid it. I was hoping that listeners would basically have to confront that piece right from the very first note that they heard. It took 16 years for me to figure out what would be the second track on the album.

UMS: And how did the theatrical aspect of the live performance come to be?

When I was growing up in the early 70s, people like Pierre Boulez were saying that the string quartet was dead. Well in August of 1973 when I heard Black Angels, I knew that he was wrong. That one piece has so much power and so much presence and it requires something not only of the players, but the listeners.

Every performance that we do of Black Angels is slightly different. We’re constantly refining the way we perform the piece, and the very first time we played it is so different from the way that we do it now that you would not even recognize it. I mean, you would recognize the music of it, but you would not recognize the visual aspect of it.

And the other thing I should say about the recording is that in the recording studio you are able to have a lot of control. We followed the timings that George Crumb wrote in the score as perfectly as we possibly could and what we noticed is that Black Angels is actually a short piece. It’s very compact. It’s also not a loud piece. It has loud moments but in general it’s a very reflective piece, with these outbursts. It just so happens that it starts with an outburst.

And so that recording influenced what we wanted to do in public performance. So we didn’t set out to create a theater piece. The piece itself is theater and we just tried to make the music come alive in the best way that we could.

UMS: Colin Stetson is performing along with you as part of a week of renegade performances at UMS. Do you know his work? What do you think of his work? What makes his work stand out for you if it does?

Well, first of all, I do know Colin Stetson’s work. I’m a huge fan. It’s not often that you encounter someone who has basically redefined an instrument. And those are the people that I like to work with. And whether it’s Astor Piazzola, or it’s Tanya Tagak, the great Inuit throat singer, or Wu Man, the great Chinese pipa virtuoso, these are people who have redefined their instrument or their approach to music. I believe that Colin Stetson belongs in the same sentence. When we were on tour in New York City, I went to hear him live, and it was an amazing experience.

Curious to know more? Read our interview with George Crumb, composer of Black Angels, or explore our listening guide to Colin Stetson.

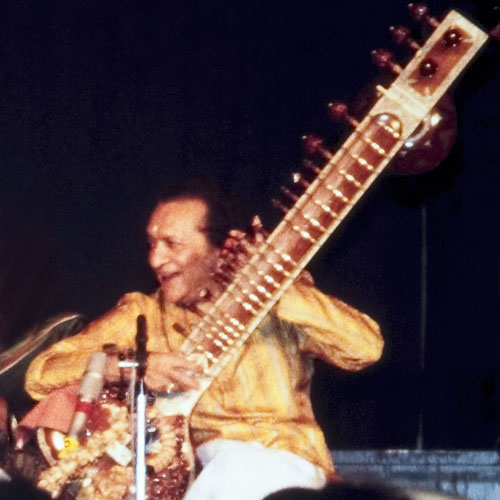

UMS Playlist: Pandit Ravi Shankar: A Retrospective

This post is a part of a series of playlists curated by UMS staff, artists, and community. Check out more music here.

Ravi Shankar in 1988. Photo by Alephalpha.

For many, the name Ravi Shankar is synonymous with Indian music. Indeed, in his nearly 70 year career he performed Hindustani (North Indian) classical music in nearly every corner of the globe, positioning him, in the words of India’s Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, as “a national treasure and global ambassador of India’s cultural heritage.” But his staggering body of work did not only pave the way for other Indian musicians. His innovations and undeniable presence on the global stage helped create the genre we now know of as “world music,” which continues to impact on cultural interaction and the way we experience culture in the modern world.

More than that, though, Pandit Ravi Shankar taught us what it means for an artist to be a true innovator. Even within the historically established tradition of Hindustani classical music, he constantly pushed forward, looking for new directions and new contexts for his music. Still, throughout this process he never lost sight of the tradition from which he came. This is the true nature of innovation: to retain the utmost humility before one’s roots, but with the fearlessness to take risks and try something new. In 2005 I had the pleasure of hearing Pandit-ji speak prior to a concert at Hill Auditorium. When asked what music his was listening to for inspiration, he answered, “I only listen to my own music.” Even then, after 60 years of recording, touring, and composing, he was still evaluating his work and striving for something more. He was 85 years old.

In this small collection from Ravi Shankar’s substantial discography, I have tried to paint a picture of the breadth of his musical life. From his early travels abroad with his brother, Uday Shankar, to his legendary performance at the Monterey Pop Festival. From his ground-breaking Concerto for Sitar and Orchestra to his collaborations with Philip Glass. From his Academy Award-nominated score for the film Gandhi to recordings he made only months before his death. His was a career that not only served as a link between India and the world, but that defined what it means to be a musician on the world’s stage.

Interested in learning more? Check out the program from Ravi Shankar’s performance in Ann Arbor in 1996.

What did you think about this playlist? Share your thoughts or song suggestions in the comments below.