Gershwin’s Unexpected Inspiration Behind ‘An American in Paris’

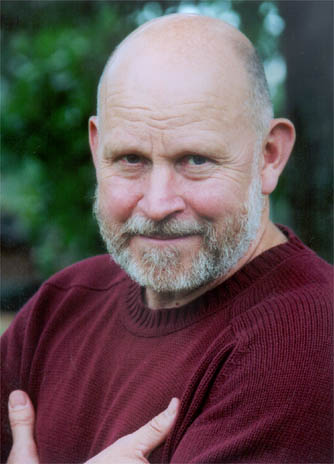

On Sunday, November 12, the Akropolis Reed Quintet will open its debut UMS recital with George Gershwin’s An American in Paris arranged by saxophonist Raaf Hekkema. University of Michigan School of Music, Theatre & Dance professor Mark Clague, also director of the U-M Gershwin Initiative, shares some background on the composer’s unexpected inspiration behind this iconic work:

Paris in the 1920s served as a kind of spiritual home for American art, especially for music as New World composers required a refuge from the pervasive influence of the German masters. Yet, the essential inspiration for George Gershwin’s tone poem An American in Paris was not the Eiffel Tower, but New York City’s Hudson River. In January 1928, Gershwin began work on an “orchestral ballet” starting with a melody he had sketched out nearly two years earlier on a trip to Paris. Contemplating this snippet which he had labeled “Very Parisienne,” Gershwin looked out from his home on 103rd Street toward the Hudson. “I love that river,” Gershwin later reported, “and I thought of how often I had been homesick for a sight of it, and then the idea struck me—An American in Paris, homesickness, the blues.” He continued to work on the piece while visiting Europe that summer.

Overall, Gershwin’s tone poem follows a three-part ABA structure in which an intrepid American traveler revels in the dizzying soundscape of Paris, is overcome by memories of home, struggles to recover, and finally triumphs over his homesickness, enthusiastically returning to the sights. Gershwin later offered this succinct program to the work:

This piece describes an American’s visit to the gay and beautiful city of Paris. We see him sauntering down the Champs Elysées, walking stick in hand, tilted straw hat, drinking in the sights, and other things as well. We see the effect of the French wine, which makes him homesick for America. And that’s where the blue[s] begins…. He finally emerges from his stupor to realize once again that he is in the gay city of Paree, listening to the taxi-horns, the noise of the boulevards, and the music of the can-can, and thinking, “Home is swell! But after all, this is Paris—so let’s go!”

In 1928, of course, the sale of alcohol was illegal in the U.S, but not in Europe. In a letter preserved in the Library of Congress, Gershwin endorses the use of An American in Paris for an anti-prohibition concert!

The piece not only captures Gershwin’s personal experiences in France, but here the composer uncovers a new depth of artistry. His early success with Tin Pan Alley songs and Broadway shows made him both hugely popular and wealthy, yet classical composers and critics remained skeptical of his aspirations to write serious music. Many dismissed works such as Rhapsody in Blue (1924) as untutored. Written just four years later, An American in Paris exhibits Gershwin’s trademark popular appeal, yet musically it is a one-movement symphony, as closely related to the economical construction of Beethoven as to the jazz stylings of Fletcher Henderson and Willie “The Lion” Smith. The musical building blocks of Gershwin’s tone poem are small motives that could only be imagined for instruments. These are repeated and passed from one voice to another in a rich tapestry of counterpoint. Gershwin’s motives represent everything from laughing passersby and taxicabs (a three-note motif featuring real car horns) to drunken tourists stumbling down the street and a brisk walking tune to accompany a stroll along Paris’s romantic Left Bank.

You may hear the colorful influence of French composers such as Claude Debussy and Les Six that Gershwin was consciously trying to evoke, as well as a bit of J. S. Bach’s famous “Air” in the bluesy “homesick” trumpet theme. The reed quintet arrangement by Raaf Hekkema of the Calefax Reed Quintet captures all the excitement, reverie, jazzy verve, and storytelling drama of Gershwin’s full orchestra original.

Listeners curious to know more might pick up Howard Pollock’s monumental study George Gershwin: His Life and Work or Summertime: George Gershwin’s Life in Music by U-M Professor Emeritus Richard Crawford. Fans of An American in Paris, in particular, might also want to rent the MGM film of the same title. It won the 1951 Oscar for Best Picture and features Gene Kelly, pianist Oscar Levant, and love interest Leslie Caron in bringing the story of Gershwin’s musical poem to life. The movie influenced a recent Broadway show.

Hear the Akropolis Reed Quintet perform An American in Paris, Sunday, November 12, 2023 in Rackham Auditorium.

Daniel Hope on ‘The Four Seasons’ and Max Richter’s ‘Vivaldi Recomposed’

Violinist Daniel Hope shares thoughts on Vivaldi’s masterpiece and its modern new take before his upcoming performance with the Zurich Chamber Orchestra on November 16.

I first experienced Vivaldi as a toddler at Yehudi Menuhin’s festival in Gstaad, Switzerland, in 1975…

One day I heard what I thought was birdsong coming from the stage. It was the opening solo of “La Primavera” from The Four Seasons. It had such an electrifying effect that I still call it my “Vivaldi Spring.” How was it possible to conjure up so vivid, so natural a sound, with just a violin?

In 1723 Vivaldi set about writing a series of works he boldly titled “Il Cimento dell’ Armonia e dell’invenzione” (The trial of harmony and invention), Opus 8. It consists of 12 concerti, seven of which — “Spring,” “Summer,” “Autumn” and “Winter” (which make up The Four Seasons), “Pleasure,” “The Hunt” and “Storm at Sea” — paint astonishingly vivid, vibrant scenes. In “Storm at Sea,” Vivaldi reached a new level of virtuosity, pushing technical mastery to the limit as the violinist’s fingers leap and shriek across the fingerboard, recalling troubled waters.

In the score, each of the four seasons are prefaced by four sonnets, possibly Vivaldi’s own, that establish each concerto as a musical image of that season. At the top of every movement, Vivaldi gives us a written description of what we are about to hear. These range from “the blazing sun’s relentless heat, men and flocks are sweltering” (Summer) to peasant celebrations (Autumn) in which “the cup of Bacchus flows freely, and many find their relief in deep slumber.” Images of warmth and wine are wonderfully intertwined. When the faithful hound “barks” in the slow movement of “Spring,” we experience it just as clearly as the patter of raindrops on the roof in the largo of “Winter.” No composer of the time got music to sing, speak and depict quite like this.

Today The Four Seasons, with more than 1,000 available recordings, are being reimagined…

Astor Piazzolla, Uri Caine, Philip Glass and others have all created their own versions. In Spring 2012, I received an enigmatic call from the British composer Max Richter, who said he wanted to “recompose” The Four Seasons for me. His problem, he explained, was not with the music, but how we have treated it. We are subjected to it in supermarkets, elevators or when a caller puts you on hold. Like many of us, he was deeply fond of the “Seasons” but felt a degree of irritation at the music’s ubiquity. He told me that because Vivaldi’s music is made up of regular patterns, it has affinities with the seriality of contemporary postminimalism, one style in which he composes. Therefore, he said, the moment seemed ideal to reimagine a new way of hearing it.

I had always shied away from recording Vivaldi’s original. There are simply too many other versions already out there. But Mr. Richter’s reworking meant listening again to what is constantly new in a piece we think we are hearing when, really, we just blank it out. In fact, working with Vivaldi Recomposed since 2012 inspired me to finally record The Four Seasons last year! In this program with UMS on November 16, pairing Vivaldi’s original with Max Richter’s brilliant new take, I feel both works inform and reflect on each other to create fresh and exciting connections.

— Daniel Hope

An Interview with Paul Neubauer, viola

A 33-year history with UMS…

Violist Paul Neubauer is set to make his seventh UMS appearance since 1986 with the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center on October 11. 21st Century Artist Intern Karalyn Schubring recently interviewed the distinguished musician about his history with the ensemble and his memories of performing in Ann Arbor.

How did you you first came to play with the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center?

“While I was a member of the New York Philharmonic, I was invited to take part in a CMS tour — which included a stop in Ann Arbor! After I left the Philharmonic, I joined CMS as a regular member. I have had countless memorable experiences in my time as part of this esteemed ensemble. Over the years, it has been amazing to study and perform interesting repertoire together around the world, during ‘Live from Lincoln Center’ broadcasts, and of course in our home at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall.”

CMS operates under a “collective” model, where different artists from their large, star-studded roster come together to play depending on the needs of each concert. What is it like to play with different collaborators all the time?

“I have been playing chamber music with hundreds of different collaborators since I started playing the viola. Everyone you work with adds to your knowledge of music as well as your own personal musical history and growth.”

The first time you came to Ann Arbor with CMS was in 1986, and this will be your sixth time back since then. Do you have favorite artists that you’ve worked with in Ann Arbor?

“Some of the programs I’ve been part of in Ann Arbor include two of my favorite singers, Anne Sofie von Otter and Heidi Grant Murphy. I also see some of my wonderful long time collaborators like violinist Ani Kavafian and cellist Fred Sherry.”

View Neubauer’s complete performance history on UMS Rewind

This season’s program, which features 13 CMS artists, celebrates composers who have contributed to our idea of the “American” sound in the 20th century, including Copland, Bernstein, Dvořák, and his student, Harry Burleigh. Is there anything about this program you’re excited to share with us?

“This is all great music and it looks like a wonderful combination of pieces. The Dvořák Viola Quintet is one of my favorite chamber works. This is sometimes called Dvořák’s ‘American’ Quintet since he wrote it during his stay in Spillville, Iowa, and you might hear an influence of Bohemian and American folk music in the work.”

What’s an important life lesson you’ve learned from playing chamber music?

“You always are working to be the best diplomat as possible when you are working with other players.”

Do you have a favorite thing to do in Ann Arbor, or whenever you’re on tour?

“Ann Arbor is of course a vibrant and exciting college town, but when you are on tour, you rarely have time to get the full flavor of a city. The usual routine is to arrive the morning of the concert, head to the hotel and try to sleep or relax, then head to the hall for a rehearsal and concert. But more often than not, there’s a party or dinner where we might celebrate the evenings performance. Maybe this visit, I’ll have more time to enjoy Ann Arbor!”

Interview conducted by University of Michigan School of Music, Theatre & Dance composition major Karalyn Schubring, who spent Summer 2019 in New York City working with Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center as part of her 21st Century Artist Internship.

Interview conducted by University of Michigan School of Music, Theatre & Dance composition major Karalyn Schubring, who spent Summer 2019 in New York City working with Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center as part of her 21st Century Artist Internship.

Carl Grapentine’s Sports & Music Playlist (Spotify and Apple Music)

More than 100,000 fans are about to be welcomed home to “The Big House” by the beloved, booming voice of Carl Grapentine, who has been the Michigan Marching Band announcer since 1970 and the official game announcer for Michigan Football since 2006.

Grapentine is also an alumnus of the U-M School of Music, Theatre & Dance, and was a host of Chicago’s WFMT-FM classical radio for 33 years. To celebrate the start of a new season at Michigan Stadium, he’s combined his expertise to curate a playlist of sports-inspired classical works and film scores. Choose your preferred streaming service and learn more about each track below:

About the Music

Honegger Rugby

Arthur Honegger’s musical depiction of a rugby match, composed in 1928 and filled with energy and power.

Mozart “Kegelstatt” Trio,

According to the autograph score, Mozart wrote this delightful trio while playing a game of skittles (a pub game related to bowling) at a local Kegelstatt—a skittles parlor.

John Williams “The Quidditch Match” from Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone

In the first match of the season, Harry caught the golden snitch giving Gryffindor a thrilling victory. Final score: Gryffindor 170—Slytherin 60.

Arnaud Bugler’s Dream

The French composer Leo Arnaud wrote this for a 1958 recording. But it’s forever associated with the Olympic games ever since ABC began using it for its 1968 Olympics coverage.

R. Strauss Olympic Hymn

Richard Strauss had a complicated relationship with the Third Reich. He composed this for the opening of the 1936 Olympic games in Berlin — the games we remember for Jesse Owens’s heroics.

Suk Towards a New Life

Did you know that the Olympic games once included competition in music composition? This was the silver medal winner (no gold was awarded) at the 1932 games in Los Angeles.

Torke Javelin

American composer Michael Torke wrote this in 1994 on a commission from the Atlanta Committee for the Olympics. Premiered by the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, it was also played at the opening of the 1996 games in Atlanta.

Puccini “Nessun dorma” from the opera Turandot

When the 1990 World Cup final was played in Rome, three soccer fans — Luciano Pavarotti, Placido Domingo, and Jose Carreras — joined forces to give an outdoor concert. Thus, the worldwide phenomenon of The Three Tenors was born. And the BBC used this aria with its climactic “Vincero” (“I will win”) for its World Cup coverage.

Sousa The National Game

John Philip Sousa was an avid baseball fan. He wrote this march for the 50th anniversary of the National League in 1926.

Horner Soundtrack to Field of Dreams

James Horner’s evocative score for the 1989 film starring Kevin Costner, Amy Madigan, and James Earl Jones.

Randy Newman “Wrigley Field” from The Natural

Randy Newman’s sometimes “Copland-esque” score for the 1984 film starring Robert Redford and Glenn Close.

Debussy Jeux

This ballet by Claude Debussy begins with three characters searching for a lost tennis ball. It was written for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes with choreography by Vaslav Nijinsky. The premiere took place in Paris in May of 1913, two weeks before the premiere of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring.

Elbel The Victors

Composed in 1898 by Michigan student Louis Elbel, in celebration of Michigan’s 12-11 victory over the University of Chicago giving Michigan the Western Conference championship. Hence, “Champions of the West.” The first public performance was given by John Philip Sousa’s band in Ann Arbor in 1899.

The Way We Remember War

“This is not the 1812 Overture, with its make-believe bravado. This is not about imagined valor — it’s about real people.”

Thoughts on Britten’s War Requiem, written by Doyle Armbrust:

I’ve always been enamored with the vivid detail with which people of my parents’ generation can recall the day JFK or MLK was assassinated: their exact location, the temperament of the weather, and the faces of those around them. My variation on that theme involves the Challenger disaster, Operation Desert Storm, and September 11. The indelible memories of the second event on this list include the front page of the Chicago Tribune (which I saved until college), watching battleships blast 16-inch shells into the night on live television, and collecting Desert Storm baseball cards. My first sentient — if safely removed — exposure to war involved deciding whether or not to trade a SCUD missile for a Dick Cheney.

There is often a disconnect between the grandeur of war and the personal fallout from it…say, the distance between the charming stories my great uncle would tell me about being a barber on a Navy ship in the Pacific in the 1940s, and the inaccessible look in his eyes while he spun the yarn. The bridging of these two realities is what makes Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem an indisputable masterpiece.

What are the first three classical music scores about war that pop into your head? For me — setting aside the Requiem for a moment — it’s Penderecki’s Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima (WWII), Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time (WWII), and George Crumb’s Black Angels (Vietnam). Well, and Beethoven’s Wellington’s Victory, which is truly one of the most cringe-worthy pieces not only by Ludwig van, but by any composer, ever (seek it out and prepare for a belly laugh). In any case, the element that each of these three war-themed pieces share with the Britten is the reckoning with the horrors of war on a personal and even spiritual level. This is not the 1812 Overture, with its make-believe bravado. This is not about imagined valor — it’s about real people.

The War Requiem consumed Britten during the years of its writing, and looking back, it’s hard to imagine that a more perfect structure could have been chosen for such a monumental piece or the solemn occasion of its premiere. In 1962, the consecration of the new Coventry Cathedral, which was erected next to its bomb-ravaged predecessor, was a study in the stirring juxtaposition of “then and now.” Britten, one of the most erudite and deep-thinking composers of any era, parallels this reality by combining the historic Requiem mass (full orchestra and chorus) with contemporary poetry from the point of view of real soldiers by Wilfred Owen (chamber orchestra with tenor and baritone soloists). But he doesn’t stop there. With the inclusion of a children’s choir and organ, the implausible optimism that there is in fact hope for peace in the future merges its way into this landmark work.

I remember talking my way into the recently opened — and sold out for weeks — United States Holocaust Memorial Museum while on a school trip to Washington, DC. What had previously existed as an abstract horror in my mind finally transformed into an experience of millions of individuals. The vast became granular. After Britten’s death, an envelope containing photographs of four soldiers — all casualties of WWII — was found amongst his things. Though merely acquaintances, these tragedies made the war immediate for the composer, rather than a conceptual event. To my ears, and despite its well-formulated structure, there is a kind of emotional whiplash between the three ensembles Britten engages on stage. Keep an ear out for the third section in the opening “Requiem aeternam,” and the way the transcendence of the mass and naivety of the children’s chorus tumbles into the fraught “What Passing Bells for These Who Die as Cattle.” It is abundantly clear that this composer is not going to allow us, the listeners, to escape into warm melancholy or ex-post-facto reveling. We are going to hear from the front lines of this worldwide atrocity.

The War Requiem can project the feeling of being constantly sucker-punched on an emotional level. The most jolting of these for me is the move from the “Requiem Aeternam: Kyrie eleison,” into the “Dies Irae” portion of the piece. In the former, lugubrious, sotto voce waves in the chorus take us to a heavenly realm before brass interruptions usher in the perturbed and breathless “Dies Irae.” Here’s an excerpt of this section by the Berlin Philharmonic:

This is a movement that, for my money, “out-Carmina-Burana-s” Carmina Burana. The contradiction of both mood and writing is nothing short of shocking, and this caroming between the earth and the heavens is the rule in this work, not the exception.

How does one end a piece that is looking to the past in equal measure to the future — one in which neither heaven nor earth provide satisfactory answers? By positing a question, of sorts.

Soon after the Gulf War erupted, I decided to find a pen pal in the US Army. I began writing to a private I did not know previously, and what I recall most clearly is that I was expecting hand-written accounts that mirrored war movie action sequences. What I received were letters honestly recounting the tedium of war. The passing of hours under a blistering sun, miles from the front lines. War was not what I thought it was.

While Britten’s text on paper reads like a closer: “Let them rest in peace, Amen,” the fact that the final words from earth are exchanged between two fallen soldiers (tenor and baritone) revolving around the “pity of war” leave one thinking that there is more to this story than the memories of World War II. Will we always be doomed to repeat this horror, or is there another way?

Perhaps the way in which we remember — or forget — such a cataclysmic event provides the answer…

—

—

Doyle Armbrust is a Chicago-based violist and member of the Spektral Quartet. He is a contributing writer for WQXR’s Q2 Music, Crain’s Chicago Business, Chicago Magazine, Chicago Tribune, and formerly, Time Out Chicago.

Doyle Armbrust is a Chicago-based violist and member of the Spektral Quartet. He is a contributing writer for WQXR’s Q2 Music, Crain’s Chicago Business, Chicago Magazine, Chicago Tribune, and formerly, Time Out Chicago.

“The girl spoke of love…”

Written by Joyce DiDonato, mezzo-soprano

Written by Joyce DiDonato, mezzo-soprano

The word “masterpiece” appears often in my line of business, and while the majority of works I participate in unquestionably fall into that category, there still remains THE Masterpieces: those holy relics of unparalleled genius that have changed the course of the art form entirely. Winterreise is this singular, crowning achievement in song.

And yet, as much as I have always loved the great recital repertoire, it never once occurred to me to personally tackle this mammoth undertaking until, just over a year ago, when Yannick Nézet-Séguin approached me with the bold idea of performing Schubert’s masterful journey together. Naturally, I was compelled to give it great consideration: “But it must really speak to you”, he warned. “You must feel deeply called to enter into this world and live there for some time.”

And so naturally I dove in. Completely. And yet, diligent as I was, I couldn’t quite find my way into the protagonist’s world, despite the utterly compelling journey in front of me. It wasn’t a question of gender – I’m used to donning pants on the stage. No. Instead, a persistent question took hold of me and simply wouldn’t let go: “But what about her?” my heart kept asking.

In most writings about this cycle, authors gloss over her involvement dismissively: “We don’t know much about her,” the papers reveal, and the discussion promptly closes.

Joyce DiDonato as Charlotte with Vittorio Grigolo as Werther in Werther, Royal Opera House. Photo by Bill Cooper

Perhaps it’s my identification with Charlotte in Massenet’s Werther that kept this question front and center in my mind. (I’ve always wondered what happens to her when the curtain comes down. Does she cave in to her passion and follow Werther into his fate of suicide? Does she obediently return to her life with Albert, dutifully, yet completely hollowed-out?)

This girl — this catalyst – that prompts our protagonist to flee his life, to embark on his pilgrimage of sorrow and despair, and to journey into oblivion presumably must know of his departure. She must feel it. She must surely wonder about him … after all, she “spoke of love”. Has she mourned his loss? Has she simply gone about her life as is expected of a girl of her stature? How has she moved forward in her life?

This lingering question provided no resolution in Müller’s poetry, and so I set out to create my own story: what if He sent His last journals to Her before he parted? A tormented and painful a scenario to face, what if His final words arrived to her as a kind of suicide note? What if He wanted Her to understand Him? To feel His pain? To experience His torment and despair? To force her to wander alongside Him? And what if She reads the writings? Word for word. Over and over. (“Ces lettres … ces lettres”, Charlotte screams out.)

What happens to the winter’s journey when we feel it through the heart of the one who was the impetus of such agony and despair? The survivor. The one left behind. What does a singular event look like through the differing eyes of two separate people, two separate perspectives? The lives that have entwined so closely cannot be separated or disregarded so easily.

Perhaps one element of a true masterpiece is that it invites itself to be experienced in new light.

So what about she who spoke of love? This can also be her journey …

Hear Joyce DiDonato and Yannick Nézet-Séguin perform Schubert’s Winterreise on Sunday, December 16.

The Great Pipe Organ

From April to October 1893, the World’s Columbian Exposition—called the “White City” for its alabaster architecture and its nightly illumination by millions of electric lights—drew the rapt attention of much of the world. Some 27 million people traveled to Chicago’s Jackson Park to see it. Of these, several hundred thousand entered the 10,000-seat Festival Hall to hear what was widely regarded as one of the greatest musical instruments—and certainly one of the largest—ever constructed.

It was a 3,901-pipe organ, 34 feet wide by 25 feet deep, 38 feet tall at its highest point, manufactured by the Farrand & Votey Company of Detroit to specifications drawn by the eminent organist Clarence Eddy of Chicago, incorporating features invented by Frank Roosevelt of New York City, first cousin to Theodore Roosevelt. It was one of the first great organs to rely on electrical connections from its keys to its pipes, which ranged from the size of soda straws to the size of tree trunks. Together they could replicate the sounds of a vast symphony orchestra.

Photo: The Ferris Wheel at the World’s Columbian Exposition

Over the six months of the fair, “the most eminent of contemporary organists” entertained crowds at 62 recitals in all. On the fair’s last day, Clarence Eddy himself wrote of the organ that “musically, it is worthy of rank among the few great organs of the world, while from a technical standpoint it occupies a supreme position.

Later the following winter, long after the last fair-goers had gone home, workmen entered Festival Hall, took the organ apart, packed the pieces in crates, and loaded the crates on rail cars bound for Cincinnati. After a few months in storage, the parts were packed up again and shipped to Ann Arbor.

In the era before radio and high-quality phonographs, when symphony orchestras were relatively rare, Americans of the late 19th and early 20th centuries listened to great pipe organs with a mixture of technological awe, local pride, and aesthetic rapture. Cities competed to buy the biggest and best. The steel baron Andrew Carnegie, famous as the benefactor of city libraries, also gave millions for municipal organs. Community fund drives were organized to buy instruments made by the most prestigious manufacturers and played by the most famous musicians. When the preeminent organmaker Ernest Skinner installed a new instrument in Cleveland in 1922—”The Finest Musical Instrument ever built by man,” ads said—a crowd of some 20,000 swept past police to squeeze into an arena built to hold only 13,000. (The show went on as planned.) The richest Americans had genuine pipe organs installed in their homes, and a new industry grew up to provide humbler home organs for the middle class.

For many years before the Columbian Exposition of 1893, Henry Simmons Frieze, professor of Latin and three times the University’s interim president, had argued for the installation of a first-class organ on the campus.

Frieze was the progenitor of Michigan’s musical tradition. A fine amateur organist, pianist and conductor, he launched student bands and choral clubs and introduced organ music to the daily chapel services. He persuaded the Regents to appoint the first professor of music. He was the principal founder of the University Musical Society (UMS), which was to make Ann Arbor a national center of fine music.

Frieze believed the shared experience of music was essential to a liberal education and to community life, and students agreed. In 1874, student journalists proposed a scheme by which a fine organ could pay for itself in six months through the sale of ten-cent tickets to all those who couldn’t afford a piano in their homes.

“Music,” they wrote, “good refining music, at a low price, is what the thousand homeless students and the poor people of this city are craving, and they will gratefully acknowledge as a benefactor whoever will furnish it to them.”

No benefactor stepped forward, and Frieze died in 1889, but his campaign for an organ soon was taken up by the University Musical Society. It was led by Professor A.A. Stanley, first dean of the new School of Music (and co-composer of the beloved U-M anthem Laudes Atque Carmina), and Francis W. Kelsey, professor of Latin (and namesake of the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology). Both were indefatigable organizers. First they raised money from townspeople to construct a new building for UMS. Then the two professors set their sights on Chicago, where, in the wake of the Columbian Exposition, the great Farrand & Votey organ was for sale.

The country was in the midst of a financial depression. Farrand & Votey had rented the organ to the Exposition for $10,000. Now they were asking a purchase price of $15,000—nearly $400,000 in 2010 currency. The University was in no position to pay such a sum for a musical instrument, however grand.

So Professors Kelsey and Stanley designed a public appeal. Major donations came from U-M alumni and music enthusiasts in Ann Arbor, Detroit, Grand Rapids, Chicago, and New York. More was raised through the sale of tickets to a grand inaugural concert—$5 to cover the cost of the concert plus train fare from anywhere in the state.

It was enough. For five months, workmen reassembled the organ in the auditorium of University Hall, then the central building of the campus, fronting State Street just east of where Angell Hall stands now.

On December 14, 1894, before a full house, Professor Kelsey declared that the organ was to be named in honor of Henry Simmons Frieze. Then he formally turned it over to the Board of Regents.

“Its splendid harmonies will ever please,” Kelsey said, “but those keys, touched by master hands, will speak a deeper message than that merely of beauty, of aesthetic pleasure. This organ will become an educational force in the hearts and lives of our young people…. May it touch and thrill their inmost natures…lifting them away from that which is mean and trivial into the clear shining of the ideal.”

* * *

Photo: Hill Auditorium stage in 1913.

The organ was played in University Hall for nearly 20 years, including at twice-a-week vesper services. In 1913, it was once again disassembled, moved a couple hundred yards to the north, then re-installed—with $16,000 worth of additions—as the centerpiece of the new Hill Auditorium. (It took an estimated 100 wagon trips to roll the components over to the new site.) It was played at countless performances, including regular “Twilight Recitals” for students enjoying late-afternoon respites after class.

In 1928 most of the organ’s parts were replaced in a major overhaul by Ernest Skinner—the designer whose installation in Cleveland had caused a near-riot six years earlier—but the new instrument remained the Frieze Memorial Organ. Further reconstructions and additions followed in 1955, 1985, 1990 (after extensive damage from a roof leak) and 1995, when digital circuitry and solid-state components were added.

According to James Kibbie, U-M professor of organ, the Frieze instrument now contains “120 ranks [of pipes] plus an additional 4 ranks in the Echo division above the central skylight, totaling 7,599 speaking pipes.” Of those 120 ranks, a dozen ranks remain from those that were manufactured at Farrand & Votey’s factory in Detroit—the last original components of the Frieze Memorial Organ.

Celebrate this Valentine’s Day on Sunday, February 14, 2016 at 4 pm with the UMS Choral Union Concert: Love is Strong as Death.

(Sources include James O. Wilkes, Pipe Organs of Ann Arbor (1995); James Kibbie, The Hill Auditorium Organ; James B. Angell, “A Memorial on the Life and Services of Henry Simmons Frieze” (1890); Frank D. Abbott, ed., “Musical Instruments at the World’s Columbian Exposition” (1895); Craig R. Whitney, “All the Stops: The Glorious Pipe Organ and Its American Masters” (2003), Charles H. Gray, “Musical Interests at the University of Michigan,” American University Magazine (1897); and “The U of M Organ,” The Song Journal (1895).)

This article appears courtesy of the online alumni magazine Michigan Today. It was published on May 12, 2010.

Being a Part of Something Bigger: A Student Perspective on the UMS Choral Union

Photo: Tsukumo Niwa.

Photo: Tsukumo Niwa.

Tsukumo Niwa will be a junior next year pursuing degrees in Oboe Performance and International Studies at the University of Michigan. In addition to being an active member of the UMS Student Committee and one of this season’s 21st Century Artist Interns, Tsukumo was a UMS Choral Union soprano in the 2013-14 and 2014-15 seasons. Here she writes about her experiences with Ann Arbor’s 137 year-old, Grammy Award-winning community choir: the UMS Choral Union.

I had been singing in choirs throughout Middle and High school, and I didn’t want to quit singing when I got to college. As I looked for singing opportunities, I came across the UMS Choral Union. Although my academic and extracurricular commitments keep me very busy, I found that the time commitment (2.5 hours weekly) was doable. It turned out that joining the UMS Choral Union was one of the best choices I have made at the University of Michigan.

With the UMS Choral Union, I got to experience many opportunities that I would otherwise not have experienced. I’ve met many people from different walks of life, all of whom contribute to the friendly atmosphere in rehearsals in their own way — taking attendance, leading the difficult passages by example, throwing jokes around, or simply smiling and singing away. While some members are students at Michigan like myself, others are older and have been in this ensemble for decades. I have really enjoyed the relaxed yet productive atmosphere in which I get to meet adults from the greater Ann Arbor and Detroit area, while also meeting students across disciplines and levels. Not to mention the opportunity to work with wonderful conductors including Dr. Jerry Blackstone, Michael Tilson Thomas, and Leonard Slatkin. In the past two years, I’ve sung in several Handel’s Messiah performances, performed with three different orchestras, participated in a Michigan Football half-time show with 500 singers and the Michigan Marching Band, and celebrated Dr. Blackstone’s last performance as the Musical Director of the Choral Union. It’s been a unique experience that not many other undergraduate students have shared with me, as I wish they did.

Right before the Messiah performance in 2014, one of the choir members said to the group: “Singing… is a chance to be a part of something that is bigger, to accomplish something that you can’t accomplish by yourself.” The UMS Choral Union embodies just that. Every single time I perform with the Choral Union, I know that I am playing an integral role in the ensemble, and I am able to connect with hundreds of audience members through beautiful music. I feel very fortunate to be able to share the music that I love with so many dedicated musicians.

Do you sing? New singer auditions for the UMS Choral Union will be held in August and September 2015.

Perspectives on Melody in Dvorak, Tchaikovsky, and Vasks

Artemis Quartet perform in Ann Arbor on April 19, 2015. Photo by Molina Visuals.

The Artemis Quartet’s program features two stalwarts of their usual repertoire alongside a recent work by one of Europe’s leading contemporary string composers, Peteris Vasks. Born, educated, and based in Latvia, Vasks began his musical life as a bassist before transitioning to composition in the 1970s. His experiences as a string player are likely responsible for the plentitude of pieces for string ensembles among his output. More importantly, his familiarity with the sound of string instruments equips him well to write highly evocative, highly expressive string music.

A strong melodic focus

While it may seem that Vasks, Dvořák, Tchaikovsky have little in common beyond the fact they are all European composers, this is not wholly the case. All three create music with a strong melodic focus that gravitates toward a clear lyrical style. Of course, Vasks enjoys and employs more freedom than Dvořák or Tchaikovsky, whose aesthetic choices were effectively dictated by a syntax of musical ideas shared among essentially all contemporaneous European composers. Indeed, melody is a de rigeur element of nineteenth century music, and Tchaikovsky is regarded as one of the best melodists in history. The Quartet No. 1 in D major (1871), part of the Artemis Quartet’s April 2015 program, certainly lives up to his reputation, although its tunes may not be as famous as those featured in Tchaikovsky’s ballets.

More interesting are the melodic experiments present in Dvořák’s Quartet in F Major, “American” (1893), which contains the pentatonic scale in abundance. The presence of this five-note scale, which also appears prominently in Dvořák’s Symphony No. 9, “From The New World” (1895), may have garnered the quartet’s nickname, as the pentatonic melodies suggest non-white American folk music. Dvořák wrote fondly of African-American music, which he heard while living in the United States, and it’s reasonable that he may have tried to refer to this tradition in the pieces he composed during this period.

Thinking beyond the movement

Although Vasks values melody in a very traditional sense, he treats it more dynamically than Dvořák or Tchaikovsky. As you will hear, Vasks thinks beyond the movement of one note to another; he develops color, register, and texture as well. Vasks’ string orchestra work Musica Dolorosa (1983) demonstrates this quality very clearly, moving from a mournful, romantic melody to an intense, aleatoric swarm of dissonance. Although there is no existing recording of Vasks’ String Quartet No. 5 (2008), his other quartets possess these same characteristics, despite the more limited instrumentation. Thus, it seems fair to expect the same in his more recent work.

In program notes written for his publisher, Vasks describes elements of his dramatic String Quartet No. 5 as, “atmospheric”, “a cry of utter desperation”, and, “a forgiving, loving look at a world tortured by grief and contradictions.” Structurally speaking, this quartet marks a departure for Vasks. String Quartet No. 5 has only two movements – being present and so far…yet so near – while the previous four all have at least three, with his String Quartet No. 4 (199) sporting five wildly contrasting movements. It will be interesting to see whether the seemingly condensed form of the String Quartet No. 5 manifests a unified and cohesive piece, or if the two titled movements simply represent two adjacent, yet individual, regions of diverse, free, and expressive musical ideas.

Interested in more? Explore our listening guide to the evolution of the string quartet.

Resident Update: Writer Robert James Russell

Writer Robert James Russell is a UMS Artist in Residence this season. We’ve asked five artists from across disciplines to take “residence” at our performances and to share the work these performances inspire. Robert shares his experiences on dance, music, and his new novel below:

“When I applied for the UMS Artists-in-Residency program, my goal was to see performances and use that inspiration to craft a new novel. I’m beyond thrilled at the chance to experience wonderful performances and explore the role of music and dance in my work—both of which have always been crucial to my mental health, and to my ability to immerse myself in a project.

So far, I’ve seen the following UMS performances, all radically different from one another—and each has inspired me in vastly different ways:

- Ryoji Ikeda (superposition)

- Mariinsky Orchestra

- Compagnie Marie Chouinard

- eighth blackbird

See, this isn’t just writing a novel, coming up with a story and characters, but in this instance I am creating an entirely new place: a fictional island in Lake Superior, documenting the entire history of the island, of the people that lived (and, in the present of my novel, still live) there. Typically when I write I find some style of music that works for that story and I listen to the same record(s) over and over as I write, never growing tire of the repetition. In this instance, though, since it’s not just story, but history…and this immersion in different types of performances has been utterly liberating:

- superposition taught me, even through the wondrous noise, about the use of silence in my work.

- The Mariinsky Orchestra inspired me to embrace more bombastic/dramatic sections of the story.

- Watching the Compagnie Marie Chouinard showed me how to re-think interactions of characters, how they meet in the story, but also how these characters interact with the island itself.

- eighth blackbird encouraged me to embrace the unexpected—to travel different routes in the storytelling, in the creation of the island’s history, of its inhabitants, and to avoid the predictable…to really dig deep and do something unique.

Each of these performances has taught me re-think what I know about art and inspiration, and they are with me every day when I write. In addition to a seemingly never-ending list of books I flip through daily—various back-issues of National Geographic featuring articles about Isle Royale (used as inspiration); a 1937 manual called Wolf and Coyote Trapping; the unbelievably inspiring/gorgeous Atlas of Remote Islands by Judith Schalansky; others—I am constantly harkening back to each performance, remembering them, and making sure that they are not forgotten. And I am reminded with every word I put down how astonishing and remarkable the performing arts are…how important they are to the production of any art.”

Each of these performances has taught me re-think what I know about art and inspiration, and they are with me every day when I write. In addition to a seemingly never-ending list of books I flip through daily—various back-issues of National Geographic featuring articles about Isle Royale (used as inspiration); a 1937 manual called Wolf and Coyote Trapping; the unbelievably inspiring/gorgeous Atlas of Remote Islands by Judith Schalansky; others—I am constantly harkening back to each performance, remembering them, and making sure that they are not forgotten. And I am reminded with every word I put down how astonishing and remarkable the performing arts are…how important they are to the production of any art.”

——

Robert James Russell is the author of two upcoming books: the collection Don’t Ask Me to Spell It Out (WhiskeyPaper Press, 2015) and the novel Mesilla (Dock Street Press, 2015). His first novel, Sea of Trees, was published in 2012. He is the founding editor of the literary journals Midwestern Gothic and CHEAP POP. You can find him online at robertjamesrussell.com and @robhollywood.”

Interested in learning more? Read our interview with Robert.

Jennifer Koh performs 2/6

Ken Fischer tells us about Jennifer Koh’s upcoming performance in Ann Arbor. Interested in going to the concert? Get more info: http://bit.ly/1rp7IPd

Artist Interview: Jennifer Koh, violinist

Insightful and passionate violinist Jennifer Koh talks with UMS Lobby contributor and composer Garrett Schumann about creative programming choices, contemporary works, and the power of music.

The virtuoso violinist returns to Ann Arbor (following her 2012 appearance in the Philip Glass and Robert Wilson opera Einstein on the Beach) with the third and final part of her Bach and Beyond series on Friday, February 6, 2015.

Garrett Schumann: Throughout your career you’ve maintained a consistent interest in programming contemporary and often newly-commissioned works alongside standard pieces in the violin repertory. Where did this passion for combining tried-and-true pieces with new pieces come from in your development as a violinist?

Jennifer Koh: I think it was always just curiosity. When you first make your foray into discovering classical music, it’s really new to you. Now, to me, it doesn’t really matter what time period the music comes from, whether it is “new” or “old.” The one thing that has been such a great pleasure about working with contemporary music is that I can actually get to meet and work with living composers, and that has been a really wonderful, beautiful part of doing the work.

GS: Do you think that putting older pieces next to contemporary work brings new things out of them?

JK: Everything is in context. We live in a certain age, and every day that passes takes us one day further away from the society of Bach, for example. I actually remember hearing a program by Peter Serkin. This program was a little unusual for him; he was doing all the Bach concerti, and what was fascinating was that everything sounded so modern. I realized that art is about re-discovering.

When I first created the Bach and Beyond program, I bookended the program with Bach because I wanted to create a journey through history and into our contemporary landscape and then return to Bach. You create this circular journey, and you realize that the experience of listening to the things in the middle changes how you hear Bach. And, in a way, it also changes how you frame each of the composers.

I feel that contemporary music links us to the past because it does have this history. Most composers work within the richness of that tradition, but they also add their personal viewpoint to it. The great thing about art, and the great pleasure for me personally as a musician, is that it has the ability to change the world. It creates a situation where people can have a space to be very present, but also go to places that they normally don’t want to go to and access those emotions that they don’t necessarily experience every day.

GS: Speaking of this sort of cyclical nature of Bach and Beyond, what’s really interesting about your performance this season is that when you did your first UMS performance in 2010, you were at the beginning of the Bach and Beyond series. Now that it’s coming to a close, how does that feel?

JK: It’s been an interesting process. I actually remember the very beginning, when it was still very difficult to convince people to do this solo violin program. And I remember when I first came up with the idea, a lot of people said, “Nobody’s going to want to book that.” Nobody does solo violin programs. But now, Bach and Beyond has become much more accepted, so one of the beautiful things for me has been that people have begun to see violin as an instrument that has enough timbre to hold an entire program.

I was also at UMS with Einstein on the Beach, and that experience opened my world in a wonderful way. Those performances were the first preview performances of Einstein, and the first extensive rehearsal process was there. It feels like UMS has been a starting point, and so it’s nice for me to return.

GS: What was the experience of working with director Robert Wilson during Einstein on the Beach like for you?

JK: It was really organic in the sense that it’s always been interesting for me to work with artists that I really admire and respect. When I first met [Robert Wilson], I was intimidated. But then, when I saw how he worked, I felt an immediate connection. I respected his working style because he is a perfectionist, and that’s something that I do myself.

When I got the call for Einstein, I knew immediately that I wanted to be a part of it. But I was actually terrified because I don’t have any acting background. But things that terrify me, I find the most interesting. For example, doing Bach and Beyond when I first thought of it was terrifying as well.

What I hope in the end for any piece, whether it’s Einstein or Bach and Beyond, is that people who actually hear the piece trust you. And that they’ll go along on the journey.

GS: Now that Bach and Beyond is wrapping up, what do you have set up for the future?

JK: My next purely performance-based project is called Bridge to Beethoven. That is really an exploration of all ten Beethoven sonatas, but will also have four new works in conversation with it.

When I first came up with the idea, I had just seen a production of Julius Ceasar by the Royal Shakespeare Company. They had made Julius Ceasar a despotic military junta leader in Africa. Again, that inspired me to think about how changing the setting can really alter our assumptions.

So when I was exploring the Beethoven sonatas, I wanted to approach the assumptions that we have in our current psychology. For a lot of people, Beethoven is the “definition” of classical music. If you say “Beethoven,” people tend to have a very specific perception of the music. The question for me, became, “How has classical music evolved?” If you look at his music, he was quite a revolutionary, but now oftentimes it’s performed such that it doesn’t sound new, it doesn’t sound modern. For me, what was important was to bring out these parts of the music that are not just “elevator music.” To really hear those revolutionary aspects in his compositional process.

What’s also interesting to me and helped to inspire this project is that I come from a non-musical background, but at one point, I discovered music is something that I love. Many American composers also come from non-musical families, so what is it about music that draws us to that platform? I wanted to create that kind of dialogue in a compositional way.

My ethnic roots are also in a country halfway across the world in Asia. How is it that I came across classical music? How is it that this art form has changed my life to the degree that I can’t imagine my life without music? Questions like this are reflected in the project as well.

Anyhow, we’re actually starting it late next season and we start it in California, then we take it to Virginia, and then it will go to New York.

GS: Well, I have to say that as a young idealistic grad student, I really appreciate the consideration you put into the program and the fact that you want to address issues that are larger than the music or parts of the music, these are things that are sometimes missed in the traditional setting.

JK: I agree. There is this idea of reaching outside of what you already know, and it’s becoming less and less common. I think that the arts are great because they are an open experience that’s about empathy, about having an experience that you don’t have on a normal basis.

Interested in learning more? Check out other interviews by Garrett Schumann.

UMS Playlist: Evolution of Chamber Music

This post is a part of a series of playlists curated by UMS staff, artists, and community. Check out more music here.

eigth blackbird. Photo by Luke Ratray.

The Chicago-based chamber ensemble eighth blackbird performs in Ann Arbor on January 17. eighth blackbird is on the new frontier of contemporary music. As Los Angeles Times explains, “the blackbirds are examples of a new breed of super-musicians. They perform the bulk of their new music from memory. They have no need for a conductor, no matter how complex the rhythms or balances… [They are] stage animals, often in motion, enacting their scores as they play them.”

How did chamber music, which originated in the Middle Ages, evolve into the music of the blackbirds? Explore the history with our listening guide:

1. Chamber music originated during the Middle Ages as a form of entertainment for guests in palace chambers. “Mille Regretz” by Josquin des Prez (1450-1521) is an example of the style and structure of sacred music translated to a secular song that describes the pain of a lost love. The earliest chamber music often also included lutes, recorders, and early versions of the violin, viola, and cello.

2. The string quartet, one of the most common chamber ensembles, developed into its current form in the early 17th century. Since then, composers from Haydn to Beethoven to Shostakovich have revered the string quartet’s form because of the challenge of writing four unique parts that constantly change and interact with one another. The string quartet includes two violins, viola, and cello. In this track, listen for Beethoven’s mastery of “counterpoint,” the relationships between the voices.

3. Chamber music in the 20th century brought together new instrument groupings. The brass (featuring two trumpets, trombone, French horn, trombone, and tuba) rose in popularity in the 1940s. Victor Ewald is widely considered to the first composer of brass quintet music.

4. Chamber music concepts extend across genre; though “chamber music” is primarily used to describe classical music, the John Coltrane Quartet exemplifies excellent chamber music playing.

5. eighth blackbird illustrates the vast range of 21st century chamber ensembles. On this track, the group performs Steve Reich’s minimalist composition “Fast: 8:39.”

6. eighth blackbird showcases its virtuosic ensemble connectivity with Thomas Adés’ rhythmically complex “Catch.”

7. eighth blackbird collaborates with electronic music composer Dennis Desantis on the track “strange imaginary remix.”

What did you think about this playlist? Share your thoughts or song suggestions in the comments below.

Prokofiev, Shostakovich, and the Year 1936

Pianist Behzod Abduraimov, who’ll perform with the Mariinsky Orchestra on January 24, 2015. The program features works by Prokofiev and Shostakovich. Photo by Ben Ealovega.

1936 was a portentous and dramatic year in the lives of Sergei Prokofiev and Dimitri Shostakovich. That summer, Prokofiev would move his family and career from Paris back to the Soviet Union under the impression that he would be able to compose relatively freely and continue touring abroad. However, when Prokofiev arrived in Moscow, his passport was confiscated. He was trapped. Meanwhile, in January of 1936, Shostakovich became a target of state-guided criticism and censorship. After rising to stardom in 1935, Shostakovich’s future as a composer was suddenly in jeopardy.

Prokofiev and Russia’s greatest expatriate composer

Prokofiev’s 1921 Piano Concerto No. 3, to be performed by the Mariinsky Orchestra on January 24, 2015 at Hill Auditorium, in many ways, symbolizes the brilliant career that he unwittingly relinquished when he returned home in 1936. Premiered by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra three years after Prokofiev’s original emigration from Russia, the work did not garner much attention for another year, when renowned conductor Serge Koussevitsky presented the piece in Paris. Prokofiev even performed alongside the London Symphony Orchestra when the concerto was first recorded in 1932.

The Piano Concerto No. 3 remains one of Prokofiev’s most popular works, and represents the composer’s appropriation and manipulation of Romantic styles and forms. Typical of Prokofiev’s piano music, the soloist’s part is impressively virtuosic and bumptious, particularly during the concerto’s rousing finale. The work’s three movements follow a traditional slow-fast-slow scheme, but its overall content is slightly more dissonant than Prokofiev’s later works, as he did not start to seek a simpler style until the mid-1930s.

Excerpt from Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 3 performed by Mariinsky Orchestra. Courtesy of Mariinsky Label. Catalog also available via iTunes.

Although Prokofiev was already well known in the West in 1921, the Piano Concerto no. 3 certainly contributed to the international success he enjoyed from 1918-1936. When Prokofiev returned to Moscow, he did so believing his career would continue as it had. Exactly why Prokofiev left Paris is unknown, but one theory involves Shostakovich’s fall from grace. Despite Prokofiev’s fame in Europe and America, he had to compete with Rachmaninov and Stravinsky for the title of Russia’s greatest expatriate composer. Seeing that Shostakovich’s career might be over, Prokofiev may have thought he could return to Russia without a rival, and enjoy the national celebrity all to himself.

“At the same time Prokofiev returned to Russia a hero, Shostakovich’s career began to fall apart.”

Shostakovich’s challenges began less than a month into 1936, when, on January 28, the newspaper Pravda published a state-directed condemnation of his hugely successfully opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District entitled “Chaos Instead of Music.” The work had received 177 performances in Moscow and Leningrad in two years, but was suddenly derided by the mouthpiece of the Soviet state. Two similar articles hit newsstands in the following months, each criticizing Shostakovich’s music on the grounds that it violated Stalin’s cultural paradigm of “social realism.” At the same time Prokofiev returned to Russia a hero, Shostakovich’s career began to fall apart.

Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 4 immediately suffered from this new government criticism. Coming off the high of Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, Shostakovich was halfway finished with the work when “Chaos Instead of Music” was published. Given Shostakovich’s new public circumstances, his friends and colleagues urged him to placate Pravda with the new symphony, which Shostakovich refused to do. He arranged a premiere performance with the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra for December 1936, but it was cancelled under ambiguous circumstances. The Symphony No. 4 did not receive it first performance until 1961, when the Soviet cultural ministry finally relaxed its expectations for Shostakovich and other Russian artists.

Excerpt from Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 4 performed by Mariinsky Orchestra. Courtesy of Mariinsky Label. Catalog also available via iTunes.

Unlike Shostakovich’s previous two symphonies, Symphony No. 4 (which is also part of the Mariinsky Orchestra’s program this January), does not feature vocalists, but rather relies on a large orchestra. It is an enormous, hour-long work that is filled with subtle suggestions of Mahler, whose music Shostakovich studied enthusiastically. The symphony’s form is unusual in its three movements of drastically imbalanced lengths. Almost bizarrely, the symphony’s outer movements are both over twenty minutes long and the inner movement lasts less than ten. However, in listening, the piece seems fairly continuous, and exhibits embryonic forms of the distinct musical characteristics Shostakovich would develop over the rest of his career.

Although Shostakovich’s Fourth Symphony was buried by the controversies of 1936, he rebounded quickly. The next year, Shostakovich premiered his landmark Symphony No. 5, which redeemed himself both with audiences and Soviet leadership. At the same time, Prokofiev was struggling with the unexpected realities of his new life in Russia. Not only was his passport terminated upon his return to the country, but he met much more resistance from the cultural ministry than he had anticipated.

For the remainder of Prokofiev and Shostakovich’s time as contemporaries, their careers were very much alike. Despite their differences, Prokofiev and Shostakovich shared in the classic dilemma of Soviet-era composers: the struggle to simultaneously satisfy one’s artistic desires and the desires of state.

Interested in learning more? Explore the Mariinsky Orchestra’s history in Ann Arbor through our archives.

Student Spotlight: Dispatch from Russia: The Real Interns of the Hermitage State Museum

Editor’s note: Polina Fradkin is a student at the University of Michigan and part of our UMS student intern team. This summer, Polina traveled to Russia for an internship with the Hermitage State Museum. Her travel blog follows, and her experiences include meeting maestro Gianandrea Noseda, the conductor of the Royal Theatre of Turin (which will perform the opera William Tell at UMS this December).

Photo: Moment from the White Nights Gala at the Hermitage. Photo by Polina Fradkin.

Right on Kazanskaya, left on Nevskiy, and through the arch into Dvortsovaya Ploschad’ — there it is, the Winter Palace in all its glory. I think I was so astounded when walking toward it every day that I took a photo … every day.

Some days, there was no work to do in the office, so I wandered the museum halls for hours, at times spending as long as twenty minutes in front of one painting. Some days, I worked for fifteen hours straight, through Gala evenings, European art biennial openings, and operas in the courtyard.

Once, I became best friends with maestro Gianandrea Noseda, the conductor of the Royal Theatre of Turin (which will perform the opera William Tell at UMS this December), and once I had to call an ambulance at two in the morning. A guest at an event had drunkenly cracked his skull in the courtyard. As I compressed the wound, I thought about writing “medical skills” under “museum internship” in my resume.

Photo: Maestro Gianandrea Noseda, the conductor of the Royal Theatre of Turin, performs outside of the Hermitage. Photo by Polina Fradkin.

Occasionally I picked up international guests from the airport, and a few times per week, I translated texts from English to Russian and vice versa for the Archaeological department. On Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Thursdays, my friend Emma and I ventured to the Storage and Restoration Facility of the Hermitage and taught English to the restorers. They fattened us up with tea and cookies, and it was a marvelous time, though I think they taught me more Russian than I taught them English.

The most mundane task of all, however, was standing at the entrance and catching people in coats or with backpacks, turning them around, and pointing them to the “garderobe” (that is, coat check). One of my most memorable experiences occurred at these entrance doors, when a certain Russian ex-pat and her American husband tried to push past us with their backpack (inside which might have fit a full grown gorilla), something for which I would have been reprimanded.

“Excuse me,” I said in Russian as I called their attention. “I’m afraid that that backpack will have to be checked.” The woman glared at me. “We were just here last week and they let us through… with the backpack,” she spat back in English. “I’m sorry, it’s protocol,” I responded. Next thing I knew, she had grabbed her husband by the arm and bulldozed through the doors. “Oh no she DI-IN’T,” I thought (or maybe even said it aloud?) as I dove inside and dragged them out by their jackets, using both hands and all of my crowd-parting might. As they finally made their way to check the godforsaken backpack, a relevant quote drew up in my mind, from Pushkin’s Exegi Monumentum: “Never argue with a fool.”

I left St. Petersburg almost penniless, but in my life, I had never felt so rich. Living in Russia sure isn’t easy. Your hummus standards drop drastically and your landlady is probably the worst person to walk the earth. Living these does, however, becomes bearable when one gets as lucky as I was and meets the best people in the world. My family, friends, roommates, co-workers, chefs, kasha addicts, kasha haters, movie watchers, and wine drinkers, French teachers, Shabbat dinner guests, Shabbat dinner hosts, brilliant Laundromat ladies, expert grocery shoppers, art savants, palace enthusiasts, opera goers, two AM bridge-parting watchers, salsa swing and waltz dancers, ogre-like but secretly wonderful flower shop owners, “let’s only speak Russian during dinner every night” attempt-ers, “Polina take the phone I can’t understand the landlady”-ers, and everyone who ever wandered into my home for the past summer, with or without warning. I miss them all terribly.

I miss falling asleep to the familiar clip-clopping of horse hooves down the street. I miss the thrill of exploring my new city. I miss living in a Tolstoy novel. I miss recognizing street names from Gogol and Pushkin tales. I miss Russia, and specifically, St. Petersburg, the place where I learned that losing hot water for weeks at a time doesn’t stop the population from going to the opera, the ballet, the museum. I needn’t have been surprised. After all, what force could interrupt the muse’s reign in Russia’s cultural capital?

Excerpt from “Exegi Monumentum”

by Alexander Pushkin

I’ve raised a monument not made by human hands.

The public path to it cannot be overgrown.

With insubmissive head far loftier it stands

Than Alexander’s columned stone.

No, I shall not die. My soul in hallowed berth

Of art shall brave decay and from my dust take wing,

And I shall be renowned whilst on this mortal earth

Even one poet lives to sing.

Interested in more? Check out other student guest blogs.

Behind the Scenes with Soprano Janai Brugger

This post is a part of a series of playlists curated by artists, UMS Staff, and community. Check out more music here.

Soprano Janai Brugger performs at our annual Handel’s Messiah on December 6-7, 2014. We had the chance to chat with Janai about her time in Ann Arbor and about what she’s been listening to lately. Check out her selections in the playlist below.

UMS: We know that you’re a University of Michigan alum. Can you talk a little about your time in Ann Arbor, and what you’re looking forward to in coming back?

Janai Brugger: It’s been five years since I graduated from the University of Michigan, so I am truly excited to return to Ann Arbor to perform at my alma mater! I have so many wonderful memories of my time at U-M, that I’m not sure exactly where to start or which ones to pick.

One of my fondest memories was attending my Studio Class with [U-M Professor] Shirley Verrett. Listening to my colleagues sing through new repertoire, seeing the process each week, critiquing, growing together was so much fun. Ms. Verrett was very adamant in asking us to always say something that we liked about a performance before listing the things we wished we could’ve done better. That was an important lesson and reminder for me during that time, and it continues to be something I remember today when I receive criticism. the class was always a supportive environment, tons of laughter, great music, and we heard amazing stories from Ms. Verrett. Our studio class was like a family, and we all looked forward to gathering together and singing for one another.

Another memory from my time at the University is meeting my husband! Javier Orman was a U-M Violin Master’s student, and we were introduced through a mutual friend. We had our first date a Pierpont Commons and talked for hours over hot chocolate [laughs]. So, in many ways Ann Arbor is very special for that reason, because I met my partner and best friend there. He’s such a wonderful person and a very talented musician and artist, whom I respect and admire more and more each day.

Janai’s Playlist:

Mozart’s The Magic Flute

I am studying the role of Pamina for my Covent Garden debut next year.

German Lieder sung by Barbara Bonney

I am singing a few song recital concerts with tons of German Lieder, and Barbara Bonney is one of my favorite interpreters of these songs

The Best of Ella Fitzgerald

I love listening to Ella sing, especially when I need a little escape from the classical world [laughs].

Motown Classics

I grew up listening to Motown artists and it’s just such great feel good music, it gets my energy going and makes me happy!

The Monster Mash hit album for kids

I’m putting this playlist together around Halloween, and my son is a year-and-a-half, so we are listening to lots of fun Halloween songs for kids. He loves it!

Selected Tracks on our Spotify Playlist:

What did you think about this playlist? Share your thoughts or song suggestions in the comments below.