Artist in Residence Spotlight: Making Art and Making a Point

This post is a part of a series of posts from UMS Artists in Residence. Artists come from various disciples and attend several UMS performances throughout the season as another source of inspiration for their work. In this post, UMS Artist in Residence Morgan Breon reflects on the UMS presentation of Us/Them.

This post is a part of a series of posts from UMS Artists in Residence. Artists come from various disciples and attend several UMS performances throughout the season as another source of inspiration for their work. In this post, UMS Artist in Residence Morgan Breon reflects on the UMS presentation of Us/Them.

Morgan Breon is a performing and literary artist. She’s an ensemble member of Shakespeare in Detroit and the Detroit Repertory Theater. Morgan’s play “A Kiss of the Sun for Pardon,” which she wrote at the age of 13 and reprised 13 years later, received the award for “Audience Favorite” at the 2015 Two Muses Women’s Playwriting Festival and the “Jury Award” at the 2015 Detroit Fringe Festival. Morgan received a dual Bachelor of Arts and dual Masters from the University of Michigan, none of which are in theatre. Her degrees reflect her passion for youth, social justice, as well as individual and community healing. These principles influence Morgan’s work as an artist, and guide her use of the arts to impact community. Morgan credits Jesus Christ with her gift of anything creative.

Walking into the Arthur Miller Theatre, the ambiance alone put me in a good mood. The quaint yet majestic theatre provided an additional element in setting the tone of: safety and intimacy. Which is often equally as desirable for young school-aged children. I was intrigued by the set! All of the pieces of the set were reminiscent of child’s play and/ or child mentality: chalkboard painted with a blue sky, sidewalk chalk lined up against the backboard, coat hooks, seatbelts extended from the sky, and a unique bouquet of black balloons. Yes, I was definitely intrigued. And no action had happened yet! But once the play started, the audience was immediately thrusted into the lives of two characters: a boy and a girl, who on thinking about it, I don’t think we ever got their names. Hmmm. (This may be intentional. But it may not. I could see arguments for both.)

During the play, I found myself engaging with the piece on multiple levels. As an actor, I thought both actors did a great job of using movement and their interpretation of the words to depict “child-like mentality.” There were very few moments where the characters weren’t in competition with each other, doing whatever was necessary — refreshing and familiar ways — to outdo the next one. (Which I loved!) This component imprinted a permanent smile on my heart, as I tend to thrive on authenticity and acute richness in my own work. My obsession was piqued by many more of these moments, such as the characters engaging in extra dialogue that often took them “out of the character” and added to their humanness.

As an artist, in general, I found myself especially inspired by the “minor details.” At one point the male actor wiped ketchup off of his face and flicked it. (Imaginary ketchup, mind you.) And guess what? The female actor responded to it! It was so subtle, but a reminder to me as an artist to challenge myself in the “details” of my artistry. Often times, I can get so caught up on the “general objective” of a project that I lose sight of basking in the details. Even the sporadic and simplistic “countdown” of the characters: “149…147…136,” indicating the number of people dying during the story was a powerful “detail” that, if left out, wouldn’t have been noticed but, being put in, provided a device that enhanced the overall impact of the play.

Yes, I was very pleased with the performance, but my “dilemma” arose after the performance when my social worker lens was applied and I started thinking about what I had just seen…and what it meant exactly. As of today, I’m still not sure. Don’t get me wrong, the performance was moving, but upon learning that it was created for nine-year-old children, my follow-up question was: to do what? During the discussion afterward, someone commented that a piece as “edgy” as Us/Them would never be shown to American nine-year-olds. I agree. But ignorance would be the culprit behind that decision — mistakenly thinking that a play inspired by violence would automatically be violent. So, this is a moot point.

As a creative, I would want nine-year-olds and above to see this because it would lead to questions, which could turn into discussion…but this may be a far reach. The reason I wouldn’t want to show it to nine-year-olds is because, in my opinion, the play sends a miscue about how to cope with trauma — especially for American children (who look like me) who experience trauma at multiple levels. As a social worker, this piece would set a young person’s treatment backward because the main message I saw was: “don’t show emotion” and/or “talk about what’s happening…without actually talking about it.” And in all honesty, too many Americans do too much of this already. The “emotionalism” that underscored the performance was provided by the audience’s foreknowledge of what the play was about. The characters never addressed how they felt. Which, may be an argument that kids rarely know how they feel (especially nine-year-olds).

But isn’t that the point? Don’t we want to get better at helping our children identify their emotions, so they won’t have to use yellow-faced and electronic emojis to express it for them? Don’t we want to aid them in identifying the root of their reactions, instead of unproductively addressing the actions themselves? I think the answer that Us/Them provides to this question is: “Ummm” (shrugging emoji). Overall, I think the artistry of the play itself motivated me to be a more responsibly detailed artist. The intended goal of the piece, however, reminded me of how important it is to either make art, or make a point. And if you aim to do both, make sure one feeds the other.

Follow this blog for more updates from Morgan throughout this season. Learn more about Renegade this season.

On Being African at the University of Michigan

Moment in portrait of myself as my father. Photo by Gennadi Novash.

Nora Chipaumire’s portrait of myself as my father is a piece of many origins. All aspects of Chipaumire’s identity as an African, a woman, a black woman, an African woman, and an African-American woman seep into her work. In this “love letter to black men,” she explores the complex tangle of conceptions, stereotypes, expectations, vulnerabilities and strengths of the black African male.

Zimbabwean influences, unique venue

A dizzying combination of Zimbabwean and African dance traditions, garb, and music help to tackle these big questions. Traditional Zimbabwean music rooted in polyrhythmic beats combines with Zimbabwean dance, an art form which requires a considerable amount of strength and agility to perform. Chipaumire uses these tools to celebrate the strength, resilience, and inherent defiance of the black body. She fuses her Zimbabwean heritage with her contemporary dance training to create this piece. Wearing traditional African gris-gris (a talisman used in Afro-Caribbean cultures for voodoo) with football pads, Chipaumire explores the black male at the crossroads of two cultures and identities.

Nora Chipaumire in portrait of myself as my father. Photo by Elise Fitte Duval.

The piece is set in a boxing ring and will be performed in at the Detroit Boxing Gym, where a program to support kids living in Detroit’s toughest neighborhoods is based and focuses on helping young black males find fruitful after-school activities to grow and develop real-life skills with positive role models.

It is not only a fitting location for Chipaumire’s exploration of black masculinity in a postcolonial world but also serves as a perfect setting for her vigorous, high-energy performance. Chipaumire has also spoken out about the brutal policing of black sexuality and masculinity, and celebrates her heritage through her art.

On Being African at the University of Michigan

African students at the University of Michigan have a unique perspective on the challenges and stereotypes Africans experience in America. Tochukwu Ndukwe, a Nigerian-American kinesiology student born in Nigeria and raised in Detroit, spoke about how his identity as a Nigerian-American student informs his experiences at the University of Michigan. In a school that is overwhelmingly white (a mere 4.4% of the population is Black or African-American), he immediately stands out.

In fourth grade, Ndukwe met a Nigerian student who embraced his culture unapologetically. This student was unafraid to educate other students about why he brought a different kind of lunch to school, or the differences between his how his parents raised him in an African household. Ndukwe was inspired by this classmate, but did not to truly publicly embrace his culture until high school. Torn between wanting to fit in with other black students and wanting to celebrate his culture in public, Ndukwe was both surprised and excited by the strength, unity, and pride of African students at the University. He now serves as president of the African Student Association (ASA), an organization that arranges cultural shows, potlucks, and mixers with other ethnic organizations on campus. Their flagship event is the African Culture Show, a massive celebration of African music and dance that packs the Power Center every year. This year’s show is titled Afrolution: Evolution of African Culture, an inquiry into the future of Africa by African students.

Ndukwe lauds African music as a crucial tether for African students to relate to the culture in their home country. He says that music allows African students to connect with their culture no matter where they are, which is especially important in Ann Arbor, which lacks the music, values, and language of their home countries.

“African music and dance are becoming more and more American,” Tochukwu says. “People there look up to America, they want to be American. African artists are beginning to collaborate with American artists, and I’m like ‘No, don’t lose your culture! It’s so rich!’” Africans are bombarded with American media and feel an increasing pressure to conform music and dance styles to that of American–particularly black American–culture, Ndukwe says.

A very loaded question

We begin discussing gender norms in Nigerian societies (he says many of the Nigerian gender norms are found throughout Africa) and a broad smile spreads across his face. “Oh, boy…you’ve asked me a very loaded question. I don’t even know where to start.”

He says, “African men are expected to be the breadwinners. They’re supposed to be strong, stoic, devoid of vulnerability. They are expected to be the disciplinarian of the family while women are expected to stay home…cook, clean, care for the children.” He explains that the expectation for men to be “macho”, and “hypermasculine” oppresses women, and that the division between genders prohibits women from getting an education and becoming financially independent.

“Mental health hasn’t even begun to be a topic in the general cultural discourse. There’s no such thing as depression, as anxiety for anyone, let alone men. So many men suffer in silence because of it.” As pressures mount for men to be sole breadwinners, disciplinarians, protectors of the family–stoic and strong–many men are subsequently unable to express their emotions with the women they care about. Ndukwe’s background as a Nigerian-born man raised by Nigerian parents tightly bound to their culture informs his relationship with women today. On a personal note, he says that he struggles to express his affection with his significant other. This leads to gaps in communication and rifts in his relationships that are often difficult to repair.

portrait of myself as my father comes at an especially important time. As the consequences of the narrow and stereotypical perception of black men enter the mainstream consciousness, this piece opens the door for discussion.

How does the representation of the black body impact the perception of self as a black woman, an African woman, and an American woman? How has colonialism seeped into the treatment of the black performing body?

Nora Chipaumire asks and investigates these questions in portrait of myself as my father.

See the performance November 17-20, 2016 at the Detroit Boxing Gym in Detroit.

Playlist: Music of Andalusia

On April 15, 2016, Simon Shaheen brings to life the Arab music of Al-Andalus and blends it with the ubiquitous art of flamenco in Zafir, a program of instrumental and vocal music and dance that renews a relationship with music from a thousand years ago. Zafir explores the commonalities of music born in the cultural centers of Iraq and Syria that blew like the wind (zafir) across the waters of the Mediterranean to Al-Andalus. There it blended with elements of Spanish music and was brought back across the seas to North Africa, where it flourished in the cities of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia.

Photo: Simon Shaheen performs on oud. Courtesy of the artist.

To offer a small taste of the music inspiring Zafir, we have compiled a playlist of music from Andalusia, the Middle East, and North Africa. While the performance will blend these three regions and show off the similarities, we’ll separate the three musical styles out here, so that you can hear how these styles have evolved and changed. Take a listen below!

Andalusia

People might think that dance is the essence of flamenco, but in truth, the heart of flamenco is the song (cante). The Arab roots of flamenco run deep, and although much of the history is obscured, it is clear that flamenco grew out of the unique culture in Andalusia. Scholars believe the word flamenco is derived from colloquial Arabic felag mangu, meaning “fugitive peasant.” The word was first used in the 14th century to refer to Andalusian Gypsies, who were called gitanos or flamencos. Soon, the term flamenco came to be applied to their music.

We’ve compiled a playlist of top flamenco musicians in the past century, which includes Camarón de la Isla, Tomatito, Paco de Lucía, La Niña de los Peines, and Carmen Linares.

Israel, Palestine, Egypt

Simon Shaheen, who will be playing in Zafir, is a virtuosic Palestinian-American violinist and ‘oud player who grew up in Israel. Until the early 1990s, Arab music from this region did not have wide distribution, so the focus was on international stars such as Umm Kulthum, Fairuz, and Farid al-Atrash.

The playlist we’ve created includes the musicians listed above.

Tunisia

Sonia M’barek, the vocalist performing for Zafir, is one of Tunisia’s most renowned singers. Her music centers on malouf, a Tunisian style of music that is based on an old Arabic type of poetry called qasidah. It features violins, drums, ‘oud, flutes, and a solo vocalist. The most important structural element of malouf, is the nuba, which was introduced to North Africa by Andalusian Muslims who were forced to leave Spain in the 14th Century.

Here is a playlist of top Tunisian musicians in the past century, which includes El Azifet, Hedi Jouini, Ali Riahi, and Anouar Brahem.

What will you listen for at the performance? Which musical thread interests you most? Share your comments below.

Zafir is at Michigan Theater on April 15, 2016.

Sources

- Tunisia, The Jewel of the Mediterranean. (n.d.) Tunisian Music. Retrieved July 29, 2015 from http://tunisia.oi-dev.co.uk/about-tunisia/culture/tunisian-music

- Noakes, Greg. (1994) Exploring Flamenco’s Arab Roots. Aramco World. Retrieved July 29, 2015 from https://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/199406/exploring.flamenco.s.arab.roots.htm

- Smadhi. Asma (2013) Seven Classic Tunisian Songs. Tunisialive. Retrieved July 29, 2015 from http://www.tunisia-live.net/2013/10/18/seven-classic-tunisian-songs/#sthash.GNvElBIV.dpuf

- New World Encyclopedia. (2013) Flamenco. Retrieved July 29, 2015 from http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Flamenco

- Pareles, Jon. (2013). Tradition Performed with a Twist. The New York Times. Retrieved July 29, 2015 from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/08/arts/music/sonia-mbarek-at-the-french-institute-alliance-francaise.html

- La Nuvola Bianca. (2015). Malouf, Traditional Tunisian Music. Retrieved July 29, 2015 from http://lanuvolabianca.com/2015/01/10/malouf-traditional-tunisian-music/

- Corrigan, Damian. (2015) Top Five Flamenco Artists. About Travel. Retrieved July 29, 2015 from http://gospain.about.com/od/music/tp/top5artists.htm

Band Geeks Unite: A Brass Music Playlist

Photo: Mnozil Brass, who’ll be in Ann Arbor on April 14, 2016. Photo by Tibor Bozi.

Perhaps I’m biased since I’m a horn player and the quintessential high school “band geek,” but the brass family of instruments is the coolest and most versatile of them all. Brass instruments are part of iconic moments in your favorite genres of music, from Shostakovich to Star Wars, and Miles Davis to OMI. Our instruments range in size, shape, and timbre, and unlike other kinds of instruments, ours only have a few valves to play any given note.

But what do brass players do when we’re not sitting in the back of the orchestra, in a jazz combo, or stepping in time with the marching band? Well, if we’re not daydreaming about John Williams or “resting our chops” (a brass player term for “goofing off”), we’re sometimes part of brass ensembles. They’re chamber groups or small ensembles, playing anything including Bach transcriptions, holiday tunes, or Top-40 Pop.

Below are some of my recommendations if you’re not sure what to expect from a brass ensemble, or a piece that features the brass section (spoiler alert: expect the unexpected). If you’re looking for the quintessential brass ensemble canon, this definitely isn’t it, but it is a wee bit of what makes this type of ensemble so engaging and fun.

Aaron Copland’s “Fanfare for the Common Man”

New York Philharmonic

No, this is not a brass ensemble piece, per se. However, it is a classic orchestral piece for brass and percussion that, when done correctly, should blow the doors off the concert hall. To play it is unforgiving, since it’s so exposed, but it’s the limited orchestration adds to its sheer power. It’s solemn, yet imbued with incredible energy that encapsulates why I love being a brass player so much.

Excerpt of Sousa’s “The Stars and Stripes Forever”

USAF Heartland of America Band, Offutt Brass

Everyone knows “Stars and Stripes,” the essential John Philip Sousa march that’s as American as apple pie. Normally, the iconic trio features the piccolo, but in this rendition, the tuba plays it. That’s right, the tuba. I traveled to Europe twice with a student honors band, and the entire tuba section did this. It highlights the tuba in a way you’d never expect from their usual on-beats (the “oohm” in “oohm-pah,” if you will) and large size. This version also features a piccolo trumpet, which is equally cool and fun.

“Twelfth Street Rag”

Dallas Brass

The Dallas Brass came to my high school during my senior year, and our brass ensemble had a workshop with them. It was terrifying and also ridiculously cool. We’d been playing their arrangements of pieces for most of the year, so naturally, playing Dallas Brass arrangements in front of Dallas Brass was pretty life-changing. This is their version of the classic “Twelfth Street Rag,” a classic ragtime piece that you might also recognize from SpongeBob SquarePants, albeit in its ukulele version.

“Bad Romance (Brass Romance)”

Canadian Brass

The world-famous Canadian Brass recreated the Lady Gaga classic, giving it a faster, uptempo feel. At first, you won’t be sure if a brass ensemble playing the greatest cultural artifact of 2009 will be cheesy or cool, since the style feels more “classical” than the synth-heavy, futuristic original. But fear not, Little Monsters. The Canadian Brass rendition gets progressively more Gaga-esque and weirder as it progresses, and as with anything Lady Gaga, that’s a good thing. You’ll want to listen to this as much as you listened to Gaga’s version on your iPod (because iPhones were barely a thing back then).

“Bohemian Rhapsody”

Mnozil Brass

If you take only one thing from this post, I hope it’s this. To me, Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody” is the height of human achievement, right up there with sliced bread and the Internet. Naturally, when I stumbled upon the Mnozil Brass version, I was intrigued. The septet uses their unique performance style to tackle a song that requires a high degree of (melo)drama, musicianship, and a little bit of sass. Sure, there are fewer white satin outfits than I expected, but there is plenty of singing, quirky choreography, and, of course, a little Wayne’s World-esque headbanging.

Mnozil Brass performs in Ann Arbor on April 14, 2016.

Zafir: World of the East

Simon Shaheen performs as part of the Zafir program on April 15, 2016 in Ann Arbor. Photo by Patrick Ryan.

The language of lyric, the spirituality of song: music embodies how a people live and feel, how they dance. As the Arabic World remains mysterious and misunderstood in the West, I encourage you to pause, be present, and immerse yourself in Zafir: the winds carrying the music of the Arabic World. Through his band Qantara (Arabic for arch), Simon Shaheen reveals the gateway to a new musical blending of cultures. Shaheen seamlessly infuses classical Arabic music with hints of Jazz, Western Classical, and Flamenco music, a blend that transcends the boundaries of both geography and genre.

Satisfying for the soul

“I want to create a world music exceptionally satisfying to the ear and for the soul,” says Shaheen. “This is why I selected members for Qantara who are virtuosos in their musical forms.”

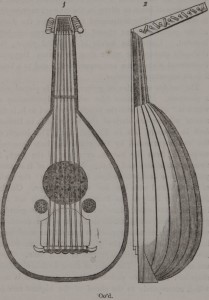

Shaheen himself is a violin and oud virtuoso (the oud is a traditional Arabic instrument and the predecessor of the western lute). He is accompanied by guitarist, pianist, and vocalist Juan Pérez. The vocalist Nidal Ibourk provides a backdrop of classical Arabic vocal tones. These three combine their acoustic talent with the visual talents of Auxi Fernandez, a flamenco dancer. Fernandez and Rodríguez cultivate the essence of the flamenco tradition from Andalusia (southern Spain). Their cante jondo, or deep song, style is the most serious of the three styles of flamenco music. However, this duo’s tunes are lightened with sparks of Spanish folk music and punctuated with falsetas (short, instrumental measures between sung verses to accompany dance). The quartet’s combined talents as Qantara are represented in Zafir.

Shaheen, born in Palestine to a family of skilled musicians, emphasizes the influence traditional Arabic styles had on him as a child. Umm Kalthoum “used to come on the air on the first Thursday of each month,” Shaheen recalls. “I always remembered much of any new song she sang. The next morning I would…hum different parts for my father, and he would note them.”

World of the East

“Imagine a singer with the virtuosity of Joan Sutherland or Ella Fitzgerald, the public persona of Eleanor Roosevelt, and the audience of Elvis…You have Umm Kulthum,” says Virginia Danielson of Harvard Magazine. For many, Umm Kalthoum was the international sensation from the 1920’s to the 1970’s. The Egyptian-born actress, singer, and songwriter remains idolized across the Arabic World, given the nickname Kawkab al-Sharq, or World of the East. Her sensual and powerful contralto voice combines a sense of beauty with her own poetic lyrics, unfolding as a revelation of reality and experience to her audience. Her most captivating quality is the spontaneous creativity she exhibits in performance. As crowds listened to her improvise the same songs, they claimed to feel unique emotions each time: her emotions. This interpersonal relationship felt by her audience remains a defining quality of her distinct style and success as an artist, even after her death in 1975.

Umm Kalthoum’s style of improvisation is easy to spot in Shaheen. His album Taqasim: The Art of Improvisation in Arabic Music, underscores his talents as a collaborator and member of Qantara.

Qantara exists at the cultural interface between Flamenco and Arabic tradition, with emphasis on the longstanding legacy of Umm Kalthoum. “If it [Arabic culture] is kept as a kind of puzzle…then definitely there will be hate and fear,” says Shaheen.

From Spain to Arabia, and everything in between, Qantara acts as an archway welcoming audiences into a surprisingly palatable and unusual world. What better way to understand cultures than through music, the language we use when words fail. As such, I invite you to uncover an artfully crafted performance that bridges and collides worlds of tradition together, right here in Ann Arbor in the Michigan Theater.

See Zafir: Musical Winds from North Africa to Andalucía on April 15, 2016 at the Michigan Theater in Ann Arbor.

References

“Bridges.” Interview by Marty Lipp. RootsWorld 2001: n. pag. Roots World. Web. 5 Jan. 2016.<http://www.rootsworld.com/interview/chava-simon.html>.

Campbell, Kay H. “Biography.” Official Website of Simon Shaheen. N.p., n.d. Web. 05 Jan. 2016.

Campbell, Kay H. “Simon Shaheen.” Aramco World May-June 1996: n. pag. Aramco World. Web. 5 Jan. 2016.

Danielson, Virginia. “Umm Kulthum Ibrahim.” Harvard Magazine. Harvard Magazine Inc., 01 July 1997. Web. 05 Jan. 2016.

Explore: Connections Between UMS and U-M Museum of Art

Visual and performing arts have a close relationship. We asked our partners and friends at UMMA (U-M Museum of Art) to link performances on the UMS season with visual art works that are part of the museum’s permanent collection.

Related performance: Tanya Tagaq in concert with Nanook of the North

February 6, 2016

Artwork: Kenojuak Ashevak (Canadian, 1927-2013). Sun Owl, 1963. Stonecut print on paper. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Eugene B. Power, 1964/2.103

Artwork: Kenojuak Ashevak (Canadian, 1927-2013). Sun Owl, 1963. Stonecut print on paper. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Eugene B. Power, 1964/2.103

Like Tanya Tagaq, Kenojuak Ashevak was from Nunavut and her art was inspired by her Inuit experience. She often depicted animals from the Arctic such as this owl, but, also like Tagaq, she relies on her creativity and imagination. Ashevak explained that she drew as she thought, and so she produced spontaneous and improvisatory images.

Related performance: Camille A. Brown & Dancers: Black Girl — A Linguistic Play

February 13, 2016

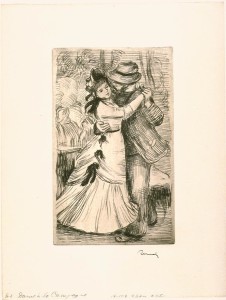

Artwork: Pierre Auguste Renoir (French, 1841-1919). Dance in the Country, c. 1890

Artwork: Pierre Auguste Renoir (French, 1841-1919). Dance in the Country, c. 1890

Soft-ground etching on paper. Museum Purchase, 1959/1.102

In Renoir’s beloved image of country dance we see an earlier century’s ritual of recreation. Although more restrained than contemporary dance, it represents social dance, one of the inspirations for choreographer Camille Brown’s work.

Related performance: Nufonia Must Fall

March 11-12, 2016

Artwork: P. Grasnick (n.d.). Aelita, 1924

Artwork: P. Grasnick (n.d.). Aelita, 1924

Lithograph on buff woven paper, laid down on canvas. Gift of James T. Van Loo, 2013/2.233

This poster is for the movie Aelita, which is often called the first Soviet science fiction film, created during the sometimes hope-filled beginnings of the Soviet Union. A mysterious radio message is beamed around the world, and among the engineers who receive it are Los, the hero of the film. Aelita is the daughter of Tuskub, the ruler of a totalitarian state on Mars. With a telescope, Aelita is able to watch Los who obsesses about being watched by her. He builds a spaceship and travels to Mars where he is thrown in prison, begins a proletarian uprising and experiences the confusion of reality and fantasy. While Nufonia Must Fall is no sci-fi film, it is based on a graphic novel of the same title, and viewers might find similarities between the genres.

Related performance: Gil Shaham Bach Six Solos

with original films by David Michalek

March 26, 2016

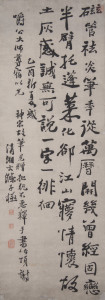

Artwork: Shitao (Shih-t’ao; Chinese, 1642-1707) Ode on a Wanli-era Imperial Brush Ink on paper, 1705. Museum purchase made possible by the Margaret Watson Parker Art Collection Fund, 1965/2.75.

Artwork: Shitao (Shih-t’ao; Chinese, 1642-1707) Ode on a Wanli-era Imperial Brush Ink on paper, 1705. Museum purchase made possible by the Margaret Watson Parker Art Collection Fund, 1965/2.75.

Taking an honored and beloved corpus of music from the past, Gil Shaham transforms its familiar beauty into a fresh, contemporary work of art. Similarly, Shitao receives a beautiful gift, a porcelain-handled calligraphy brush, from an earlier generation and uses it to write a poem and create a calligraphic masterpiece. The era and form are new but the inspiration is classic.

Related performance: Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán

April 1, 2016

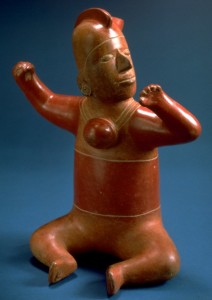

Artwork: Artist Unknown, Mexican, Colima Culture Seated Figure, c. 700 Terracotta Museum purchase made possible by a gift from Helmut Stern, 1983/1.355Artist Unknown, Mexican, Colima CultureSeated Figure, c. 700TerracottaMuseum purchase made possible by a gift from Helmut Stern, 1983/1.355

Artwork: Artist Unknown, Mexican, Colima Culture Seated Figure, c. 700 Terracotta Museum purchase made possible by a gift from Helmut Stern, 1983/1.355Artist Unknown, Mexican, Colima CultureSeated Figure, c. 700TerracottaMuseum purchase made possible by a gift from Helmut Stern, 1983/1.355

This lovely terracotta seated figure is an example of the native arts and culture celebrated by Mexican visual and musical artists. Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán transform a regional folk music into a world-class art form.

Related performance: Zafir: Musical Winds from North Africa to Andalucia

April 15, 2016

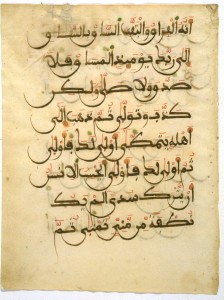

Artwork: Artist Unknown, North Africa Qur’an manuscript leaf in Maghribi script, 13th century Ink, red ochre, paper Museum Purchase, 1959/1.146

Artwork: Artist Unknown, North Africa Qur’an manuscript leaf in Maghribi script, 13th century Ink, red ochre, paper Museum Purchase, 1959/1.146

For Muslims, Arabic script, representing the language of the Qur’an, is a thing of sublime beauty. This page is written in a script called Maghribi, a variation of the earlier, angular, Kufic script. Maghribi features sweeping curves that loop across the page and was developed in North Africa and Spain. This Qur’an page combines traditions of the Middle East, Spain and North Africa as does the music of Simon Shaheen and Zafir.

Interested in more? Visit the U-M Museum of Art today.