Student Spotlight: Greg Hicks on How Max Raabe’s Tailored Tuxes Will Open Your Mind

Photo: Max Raabe rides his bicycle. He performs with his Palast Orchester on April 9, 2015 at Hill Auditorium. Photo by Marcus Hoehn.

Max Raabe and Palast Orchester are a well-groomed lot, both musically and visually — trained at the Berlin University of the Arts, tux-friendly, hair parted to one side — and that very sense of aesthetic perfection is what makes Raabe and company so unpredictable. While every tux is tailored to perfection and every stray hair is combed into place, Raabe’s creative persona throws the experience of the performance off-kilter in the best way.

The Raabe method of approach is to give a taste of vintage formality to a situation that might not require it. Past examples from Raabe include (but are not limited to):

- Using a condenser microphone to sing a live cover of Britney Spears’s “Oops…I Did It Again.”

- Wearing a tux while singing a cover of Queen’s “We Will Rock You.”

- Singing the 1930s hit “Dream a Little Dream” at music festivals.

Take a walk through Max Raabe and Palast Orchester’s photo gallery and you’ll get the same impression. You’re greeted with a photo of Raabe riding a bike — no-handed — through a city road whilst wearing his classic tuxedo, giving a casual grin to the photographer.

The Palast Orchester. Photo by Marcus Hoehn.

As you continue your photo exploration, you’ll find Raabe and the eleven other members of the Palast Orchester crammed into a paddleboat, instruments in hand, dressed in tuxes, casually floating along the lake. In further shots, Raabe is photographed mostly-submerged in the lake, head popping out, staring directly into the camera — still dressed in his tux. Oh, and there’s also a duck floating past him.

Why the constant throw-back attire, Mr. Raabe?

For one thing, cherry picking visual styles all the way back to the 1920s establishes an image to “not look the type” to perform contemporary music brands — allowing Raabe to shock and surprise audiences with well-orchestrated versions of relatively modern radio hits like “Oops…I Did It Again” and “We Will Rock You.” And Raabe isn’t the only notable artist to visually belong to one era of music while successfully surprising listeners with renditions of another.

Last year, pop sensation Lady Gaga showcased a similar visual deception — though in her case, pop aesthetic combined with jazz standards. Unlike Raabe, Gaga often exemplifies the most contemporary, dynamic image in her style, and on her latest record Cheek to Cheek, Gaga melded this persona into a record consisting of classic jazz hits sung with jazz icon Tony Bennett.

World-wide pop-rock sensation Robbie Williams (who often displays a “bad boy” stylistic persona) used a similar technique on his unexpected 2001 jazz standard cover album Swing When You’re Winning and again in 2013 with Swings Both Ways.

Pop diva Christina Aguilera went so far as to release an album of entirely original tracks in throwback production style on Back to Basics. Aguilera, Williams, and Gaga were all heavily praised for their surprising capabilities to sing in these unexpected genres.

And here on the flip side, we have Max Raabe, who takes a vintage image and displays his capabilities in the realm of popular music.

The visual foundation of the German old-style group is something that, upfront, audiences might take very seriously, given the formal vintage look. But upon observing the group’s surprising photoshoots and song cover choices, a new open-mindedness with a taste for the abstract and a quirky sense of humor might unfold.

When Max Raabe and the Palast Orchester performed previously in Ann Arbor, UMS gave fans the opportunity to sample their own vintage attire in an in-venue photo booth, and the same is encouraged this year. Come dressed in your best 1920s fashions, but don’t forget to bring your sense of humor as well!

Max Raabe and Palast Orchester perform at Hill Auditorium on April 9, 2015.

Interested in more? Explore even more audience photo booth photos from Max Raabe’s last appearance in Ann Arbor.

Artist Interview: Jaco van Dormael, Co-creator of Kiss & Cry

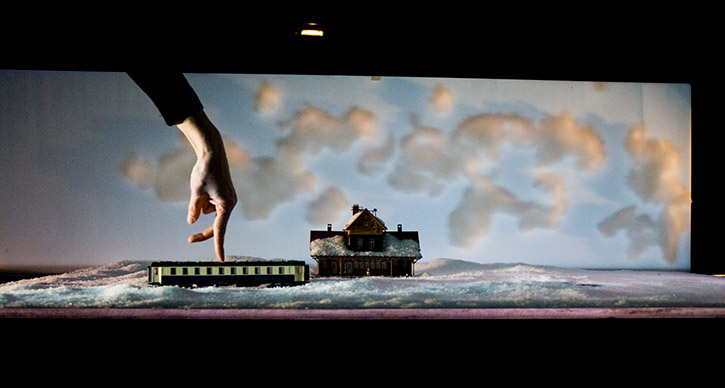

Photo: The set of Kiss & Cry, at Power Center October 10-12, 2014. Photo by Marteen Vanden Abelee.

Jaco van Dormael and Michèle Anne de Mey are bringing their one-of-a-kind finger ballet Kiss & Cry across the globe and to Ann Arbor. The performance runs at the Power Center October 10-12, 2014.

Dormael is a critically acclaimed Belgian film director and screenwriter, famous for his award-winning films, including his most recent cinematic hit, 2009’s Mr. Nobody. UMS Lobby contributor Greg Hicks recently spoke with Jaco van Dormael about the unique process of assembling Kiss & Cry, all the way from its minimal beginnings to its full-fledged stage production.

Gregory Hicks: How did you go about assembling the creative team for Kiss & Cry?

Jaco Van Dormael: [Michèle and I] had never worked together, so at the moment we were thinking “What could we do to work together?” She is a choreographer and I’m a movie maker. At the beginning, it was something that was new for everybody. Personally, I wanted to make something very little. I spent the last 10 years on a big film that I liked very much, so I wanted to do something small.

So, the challenge for me was: “Is it possible to make a long feature film on the table of the kitchen?” For Michèle, the question was, “Is it possible to dance only with hands?” We started improvising in the kitchen on the table with a tiny camera and a few friends — trying to figure out how it’s possible to give big feelings with tiny sets, and how it’s possible to make a sort of ephemeral film — a film that only exists in front of the audience, but nothing is ever recorded.

GH: How does the usage of hands (as opposed to traditional stage methods) change the presentation of the story?

JDV: The important thing is that the camera shows on the screen what is too little for the eye. [On stage],you will see bodies, but on screen you will only see hands. The eye can go from the stage to the screen and have a sort of double perception.

Even the way of filming is totally new for me because the mixing of the scales is something we rarely use in cinema — to have tiny houses and tiny sets. For example, one hand is sleeping in the bed, and the hand is smaller than the pillow. But when she wakes up, she’s bigger than the bed. And then she goes into the garden and the hand is bigger than the house! Because the scales are different, it’s possible to make images that are closer to dreams than reality.

And, there is no digital effect. All the special effects are made on the spot and visible with the eyes. For example, we have a house, and we can make the gravity of switch on and off just by filming something in the box and turning it, a sort of inverted gravity. We can make things that are nearly impossible to pay for in a feature film. With two bucks, we have incredible effects! And the audience sees how it’s done. It’s like a magic trick. You can tell that it’s a trick, but you believe it.

GH: How do you think the audience will handle seeing a performance in this way? Do you think it will take them a moment to get used to the two formats once the performance starts?

JDV: I have a feeling that the audience will click immediately into the process, because you have these dancing hands from the beginning. [The audience] enjoys something that is different but familiar, a film made just for them. It’s an experience you cannot have by watching a film on DVD, and it’s an experience you cannot have in theatre either. It’s something new, something that wasn’t possible ten years ago because the tiny cameras we use didn’t exist 10 years ago. For example, we have a train that is turning around, and there are three little cameras in the train that give the feeling that we’re speeding in a large country.

GH: The students and community of Ann Arbor are always thrilled to see experimental shows. How do you feel about bringing your show to a city like as this?

JDV: It’s a joy because I think it’s made for people who want to see new things. It also works very well with young people because they already have that habit of figuring out what is possible to make [with video devices]. One of the most enjoyable remarks I heard from the audience was from a young guy who said to me, “What kills me is that these kinds of shows are made by old people!”

At the moment, we’ve played [the performance] more than 200 times in 8 different languages. It doesn’t look like a foreign theatre piece. People always see it in their own language, whether we play it in Korean or in Spanish or in German or in Dutch or in Italian. It’s always in the language of the country, so I don’t think [Ann Arbor] will need to study for anything.

Interested in more? Watch the video trailer for the performance, featuring UMS director of programming Michael Kondziolka.