Student Spotlight: Could You Repeat That? and Other Stories from Paris

Editor’s Note: Clare Brennan is a junior at the University of Michigan. This past summer she interned for ANRAT, a theater research company in Paris co-founded by Emmanuel Demarcy-Mota, director at Théàtre de la Ville. Their production of Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author comes to UMS October 24th and 25th.

The summer of 2014 consisted mainly of getting lost. As a first-timer to the grand city of Paris, or to any sort of international travel for that matter, I had incessantly practiced the correct way to ask for directions to the bus stop during my entire eight hour flight. Before I could get a “Bonjour” in edgewise, a bored flight attendant directed me towards my destination in perfect English, and I was on my way.

I’d gladly forget my first trek from the airport to the dorms, dragging my two oversized suitcases across town, but after the jetlag wore off, I started to get the hang of things. I became a lover of maps, discovering the metro system as quickly as possible. That knowledge invariably went out the window as soon as summer construction began. Eventually, I started ending up in the same places, and what was once a completely strange conglomerate of streets started feeling a little more like home.

Once settled in, I dove into the incredible wealth of theater surrounding me. With over 150 professional theaters within its city limits, Paris never let quantity deteriorate quality. One of my first shows was Ionesco’s Rhinocéros at Théàtre de la Ville. I had missed the production when it came to UMS last season, and was so excited when fellow UMS intern Flores Komatsu offered up a ticket to join him. We met at the theater and crossed one of the many bridges that connect the vastly different banks of the river to find a small café for dinner. A group of men of various ages played pétanque, the French equivalent of bocci ball, on a dirt patch next to us, a common pastime on summer evenings. Obviously American, we prattled away, catching up on upcoming projects, book recommendations, and travel plans. Eventually, the couple from Colorado sitting next to us struck up a conversation, and after twenty minutes we had learned the story of their ex-pat daughter and swapped recipes for favorite dishes we’ve discovered. Caught up in conversation, we barely realized we were running dangerously close to curtain time. We sprinted back to the theater and found our seats with just enough time to absorb the atmosphere.

*

I love theaters. Between their velvet curtains and cushioned seats, both actor and audience member gain some security to suspend their disbelief for a while and hear a story. I appreciate that sense of trust that seems built into the walls, and I always try and find it again before every show I see.

At Théàtre de la Ville, the most striking quality I found was its size, housing around 1,500. Our Monday evening show was sold out, and as I looked around, I noticed that most of those in attendance were around my age. In my exploration of the arts at home, I’ve often found truly invested younger patrons more difficult to find. There, young people come to shows, stay for talkbacks, and attend season premieres; Théàtre de la Ville’s season announcement, for instance, packed the house just as tightly as their best-known runs.

Photo: Le Palais de Pape, where “I Am” played during the Avignon Theater Festival in July. Photo by Clare Brennan

The house lights dimmed, and I experienced again what would quickly become one of my favorite culture moments abroad. Before an actor ever sets foot on stage, a score of audience members will audibly shush one another. It will be hard to forget my first experience of this sort, as the majority of hisses were directed at me. Foreign air and a lack of sleep had left me sick for a couple weeks, and, apparently, I thought that the start of the Moroccan acrobatic performance Azimut at Théàtre du Rond Point would be a lovely time for a coughing fit; the surrounding patrons did not. I quickly picked up this less-than-subtle social cue, and by the end of my two months, I was joining in as passive-aggressively as possible. Strong reactions like this were never out of place. At the Avignon Theater Festival, a production of Lemi Ponifasio’s I Am, a World War II homage in dance, produced critical laughter, side comments, even a small exodus after a particularly difficult movement. However, with this piece included, I also never saw a performance without at least five minutes of applause at the close.

*

Seeing theater in a foreign language took a bit of adjustment. Rhinocéros opens with a beautiful monologue. I couldn’t tell you what the first few lines mean now, as I was still looking for surtitles within the first few moments before I remembered where I was. I did have opportunities to try reading French surtitles during a Dutch production of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead and a Japanese kabuki style of the Mahabharata. Reading and translating French while listening to another language with which I had no experience left my American brain a little withered, but it did help me to abandon any pretenses I had when I arrived and dedicate a couple of hours to a completely new experience. Or four and a half hours, in the case of the Dutch Fountainhead. (I have to admit, I dozed off for about twenty minutes of that. I read the book in high school, so that counts, right?)

That night, Flores and I left the theater and lingered on the rainy sidewalk with a crowd of theatergoers doing the same. We all shared our thoughts, compared interpretations, raved over actors, and tried to weave our way through the denser moments. We said our goodbyes for the night, and as I turned to leave, I realized that I was pretty disoriented. I was lost in Paris again, but what else was new. Theater abroad left me dizzy and buzzing, not quite sure of where I stood but happy that I was there. I was used to the feeling by now, and there could be worse places to get turned around. Paris is a city for wandering, anyway.

Artist Interview: Traveling with Théâtre de la Ville

Editor’s note: This summer, UMS launched a new 21st Century Artist Internships program. Four students interned for a minimum of five weeks with a dance, theater, or music ensemble part of our 2014-2015 season. Héctor Flores Komatsu is one of these students. He spent five weeks with Théâtre de la Ville in Paris, France.

Théâtre de la Ville performs Six Characters in Search of An Author at the Power Center in Ann Arbor on October 24-25, 2014. Photo by JL Fernandez.

Scene

13:30, May 23, 2014, Paris, France. En route to final dress rehearsals of Six Characters in Search of an Author at Le Forum Blanc Mesnil, a banlieu (suburb) located at the northern outskirts of the city proper. Cast and production members sit throughout the van shuttle between Théâtre de la Ville and our current rehearsal space.

Les mecs (the dudes) hang out in the back, and one of their phones alternates between the American and French pop hits of the moment. Some nap, some read, some eat their lunch. They converse in the relaxed, soft, yet gutturally vibrant and “chic” French that had initially been both inviting and intimidating to my Mexican-American mélange of an accent.

Actress Sarah Karbasnikoff’s sweet, edgy, yet motherly voice, proper for her character, rises in joyous laughter, while actress Valerie Dashwood’s dark, yet subdued, cedar timbre seduces the air with chuckles, not unlike those heard from her character, the Step-Daughter. The laughter is inviting, I sit across them, speaking in “tu,” not “vous,” as they had requested.

We chat for the readers in Ann Arbor, of which Sarah has fond memories with Rhinos stampeding through the fallen autumn foliage. (Théâtre de la Ville last visited Ann Arbor to perform Ionesco’s Rhinocéros in 2012.)

Héctor Flores Komatsu: You are a very interesting mother-daughter stage pair! Could you talk a bit about your characters’ relationship in the show?

Sarah Karbasnikoff: Well, I play the Mother, who… Let’s just say she suddenly arrives at the theater with her first husband and all of her children.

HFK: Hmm…

Sarah: Ha! That’s what you need to know, I don’t think I should say more!

[Laughter]

Valerie Dashwood: As for me, I play the “Step-Daughter.” She is such because her mother…

Sarah: That’s me…

Valerie: Was initially married to the character of the Father, with whom she had…

Sarah: A boy.

Valerie: Yes, a boy… Just one boy.

Sarah: Voila!

Valerie: Afterwards, she “had” a second man, my true father, with whom she had three children of which I play the eldest, the Daughter.

HFK: What would you then say is the fundamental need, desire, of the mother, of the Step-Daughter, of the family as a whole? What is it? Is it love? Is it to unite the entire family? Is there a common desire as a family?

Sarah: Well, that will certainly differ for each character.

Valerie: For the Step-Daughter there’s no need or desire to be part the family. One of the first things she says is that she “will take off – fly away!” because she doesn’t want to be part of it.

Deep inside, she detests her Step-father, and she also hates his first, legitimate, son. She speaks a lot about legitimacy, because perhaps she doesn’t feel entirely legitimate. She doesn’t have legitimacy even within society, given that she’s had to prostitute herself to support her mother and siblings. That’s her point of view.

Her desire is, more than anything, is to self-destruct, through which she can emancipate herself from her family, become and adult.

HFK: She fights for her freedom!

Valerie: She fights for her freedom!

HFK: For the mother it seems to be quite the opposite.

Sarah: Each day I discover her a little more. At this moment I have the impression that, yes, she seeks to see her son again, that is certain, because she wasn’t there for him, and so there’s some degree of guilt. Her two youngest children die, and eldest daughter wishes to escape from her. So yes, her greatest desire is to bring everyone together but, alas, that’s impossible. Her life is her children, all of whom escape from her, leave her.

During rehearsal with Théâtre de la Ville. Photo by Héctor Flores Komatsu.

HFK: How has the process been for you, as a new actress in this restaging, stepping into a role originated by someone else?

Sarah: Well, first one must do what’s already been done and understand what already exists. I’ve been stepping into the shoes of the original actress.

And now, with each run, I begin to understand the reason behind her movements, the psychological motivations. At first they were mere just movements, crossing from one place to another, and I simply memorized them; it was very concrete, very technical work. And then, from that point, I began to create the character.

HFK: For you Valerie, having played this role in the original production twelve years ago, what has it been like this time? What has been unearthed once more? What has been newly discovered?

Valerie: What’s been really interesting for me, since it’s been twelve years since I played this role in the original production, is that upon returning to this play, I could not perfectly recall many specifics, but I still had a global feeling of the character, the violence, the pain, and of the will – that’s what it is! The will of the character, is what I remembered well.

However, I could barely remember the text – except for the song! Bizarrely, that had completely stayed with me; I remembered the song… but not my lines!

But then when we read out the play all together at Théâtre de la Ville, with Hugues [Quester, who plays the Father] and Alain [Libolt, who plays the Director], hearing their voices and feeling their energies through the text, the memory came back to me. By reading with them, I was surprised to feel the same emotions from years ago resurface, as if something which long laid dormant suddenly awoke, opening itself. Voila!

After that, relearning the text was very easy.

HFK: What is different today, than how it was twelve years ago?

Valerie: The biggest difference is that twelve years ago I didn’t have children, and now I’ve had two. So my maternal instinct, the one my character has for her little sister, feels very different. Motherhood has hit me hard, and it affects how I act, even in the way I look at the little girl. Sans resorting to any psychological tricks, I instinctively see my daughter in the little girl. I have a child now… And that fact greatly affects how I act, knowing that this little girl, in the play, will die.

I don’t think I could ever do this in the same way as I did twelve years go.

Also, having worked so much in just the past ten years, I feel much more physically available in my own body, much more reserved. At the time, the nudity had originally been somewhat difficult for me, but much less so nowadays. That scene, which I came to fear, I now approach with serenity, even when it’s hard to play.

HFK: And now for my last question for you. I’ve noticed that there’s a lot of love and care behind the scenes among the cast. And for you two, who play Mother and Daughter on stage but are much closer in friendship and in age off-stage, how does that affect your stage relationship?

Valerie: All I can say is… Just like in our previous play, I played the mother to Sandra [another Théâtre de la Ville actress who also plays one of the “actresses” in Six Characters]. I never feel the need to ask myself whether this is or isn’t “coherent,” even if we are only twelve years apart. In theatre, we have what we call, at least in French, a “convention” to suspend disbelief. So right now, Sarah may be playing my mother, and we understand each other really well, which is good because playing this relationship requires great emotional investment. We can support that off-stage. Our closeness strengthens the bond vital to plunging into the work together.

Sarah: For me it’s very similar. During the show I don’t think at all about the age difference. To feel Valerie as she plays her character, I do nothing more than to say “she’s my daughter.” That’s it, I don’t see the age at all. There’s also an understanding of our respective pains, because we know each other personally. That really gets me, it truly does. She does, her pain. She might not truly be her character, but we form an affinity, a bond.

We streamline into casual conversation, and soon enough arrive at the theater. An hour into the rehearsal, as everybody gets into costume and warms into their roles Valerie receives a phone call. Her youngest child isn’t feeling well. She ponders the symptoms, trying to figure the right remedy. There’s the natural concern of the working actress-mother in the midst of rehearsals. She seeks her stage-mother Sarah, a veteran mother in various senses, for reassurance. That’ll do it,” Sarah says. For a moment, the parallel lines of reality and fiction intersect, not unlike in the play, as the two women connect through maternity.

Interested in more? Look for Flores’s behind-the-scenes photo-essay covering his time with the company.

Who Are We?

Théâtre de la Ville performs Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author at the Power Center in Ann Arbor on Oct 24-25, 2014. Photo by JL Fernandez.

While I was working on a biography of poet, playwright, and theatre director Federico García Lorca many years ago, I was startled to discover that Lorca had planned to meet up with the dramatist Luigi Pirandello in Italy in 1935. The two intended to collaborate—but Lorca cancelled the trip after Mussolini invaded Abyssinia (it was one of the rare overtly political gestures of Lorca’s life), and the two men never met.

I’ve often wondered what would have happened if they had. For both playwrights shared, among other things, a fascination with the nature of theater. Lorca probed the topic throughout his life, in plays that contain plays and rehearsals within plays, plays whose cast lists include directors and actors and playwrights (including Lorca himself). He introduced all manner of theatrical claptrap into these works—puppets, masks, screens (behind which identities abruptly change), miniature stages, outlandish costumes and props.

Pirandello was similarly obsessed. You see it big time in Six Characters in Search of an Author, a play that, if done well, should produce something like imaginative whiplash in the audience. (I’ve only seen the work produced once, in a student production at NYU, with way too much scenery-chewing. But having seen Théâtre de la Ville’s exquisitely nuanced production of Ionesco’s Rhinoceros two years ago in Ann Arbor, my hopes are high.)

What’s real? Who’s acting?

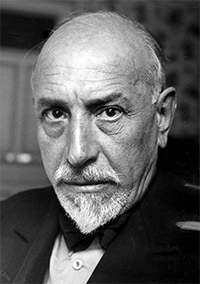

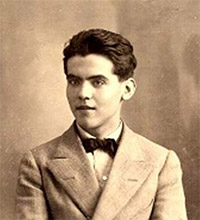

On left, Luigi Pirandello, and on right, Federico García Lorca.

What’s real? Who’s acting? Are the events and emotions we see onstage reality? Is what we experience and witness in “real life” acting? Can you trust what you see on a stage? In a conversation with your spouse or best friend or boss?

Aren’t these the questions that lie beneath the pleasures we associate with theater? (With film too, but I don’t think the experience is ever quite as acute on a screen.)

The setup for Pirandello’s exploration of theatrical artifice is straightforward: six purportedly fictional characters barge into a mostly empty theater to impose their story on a director and group of actors who are trying to rehearse a play. Actors become audience. Characters become actors. The layers multiply and confusions mount.

In line after line, we’re asked to consider the contradictions at the heart of play-making.

DIRECTOR: Then the theater is full of madmen, is that what you’re saying?

FATHER: Making what isn’t true seem true … for fun … Isn’t that your purpose, bringing imaginary characters to life?

Elsewhere the Father—one of Pirandello’s “six characters”—cries out that his story isn’t literature, it’s “life! Passion!” To which the Director responds: “That may be, but it won’t play.”

“What’s a stage?” a character asks toward the end of the play, and answers her own question. “It’s a place where people pretend to be very serious.”

The Empty Space

Exchanges like this abound—and make you question the theatrical enterprise and its conventions. Do we really need all the devices we’ve come to associate with the theater? The curtain and spotlights and scripts and applause? Peter Brook famously said (in his indispensable 1968 book The Empty Space) that in order for an act of theater to take place, all you need is for one person to walk across an empty space while another watches.

Brook published his book some 40 years after Pirandello wrote Six Characters, which opens on a stage whose atmosphere, Pirandello instructs, “is that of an empty theater in which no play is being performed.”

The Italian Pirandello grew up steeped in the venerable stuff of theater—the comic and tragic masks of the ancient Greek and Roman stage, the stock characters of thecommedia dell’arte. He understood (as did Lorca and that greatest of playwrights, Shakespeare) that identity is at the core of acting. As one of Pirandello’s six “characters” points out, “We all try to appear at our best, but we all know the unconfessable things that lie within the secrecy of our own hearts. We are not what we seem—even to ourselves.”

Don’t you change your personality according to the situation and your audience?

In another book I find indispensable, The Actor’s Freedom: Toward a Theory of Drama (1975), critic Michael Goldman probes precisely these questions. Identification is the “covert theme of drama,” Goldman writes. This isn’t simply a matter of actors identifying with roles but of “the making or doing of identity.” You watch an actor, onstage or on screen, and wonder where her private life stops and the public, performed one begins, what parts of herself we see revealed in her role.

“It should not be surprising, then,” says Goldman, “that the process of identification in this sense—of establishing a self that in some way transcends the normal confusions of self—is remarkably current as a theme in plays of all types from all periods, from Oedipus to Earnest to Cloud Nine.” Add Six Characters to that list.

And what about us? Are we characters—locked into our one and only story? Or actors, whose “solid reality as of this moment is destined to become the half-remembered dream of tomorrow,” as Pirandello’s Father puts it?

Questions to ponder, indeed. Endlessly.

Leslie Stainton’s most recent book is Staging Ground: An American Theater and Its Ghosts, a poignant and personal history of one of America’s oldest theaters, the Fulton Theatre in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

Student Spotlight: Summer with Théâtre de la Ville

As part of the 21st Century Artist Internships program, U-M students spend several weeks working with companies that are part of the UMS season. In 2014, 21st century student Héctor Flores Komatsu worked with Théâtre de la Ville in Paris, France.

Below, Flores shares his travel stories with the company. Théâtre de la Ville returns to Ann Arbor with L’État de siege (State of Siege) on October 13-14, 2017.

El Espíritu Oculto de la Olvidada Europa

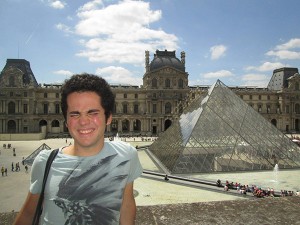

Photos: On the left, Flores in Paris. On the right, the company during dinner. All photos by Flores Komatsu.

The word “summer” has always had a very homey and rooted connotation to me. Road or plane trips that traverse borders were a staple of my upbringing. I’d look forward to the summers of eternal spring in my Mexican hometown, under the shade of the oscillating bugambilias, tantalized by the scent of Sunday morning house-spiced chorizo at my grandfather’s. If I owe my curiosity and affinity for the intercultural richness of the world to anything, it’s to the very familiar act of crossing borders.

I finally had the opportunity to venture away from the continent this summer, after Jim Leija [UMS Director of Education & Community Engagement] called to invite me to intern for UMS in Paris as part of the new 21st Century Artist Internship. I’d be leaving for France in three weeks.

And so, I took-off to Europe to intern with Théâtre de la Ville, Paris’s cultural institution for the performing arts (as well as an Ann Arbor and UMS favorite, having performed Ionesco’s Rhinocéros at the Power Center two seasons ago). I’d be working as a rehearsal assistant and media collector for their upcoming touring production of Six Characters in Search of an Author (to be performed at the Power Center October 24-25, 2014). All this presented itself, serendipitously, a mere two weeks before the end of my sophomore year at the University of Michigan — truly, an open door. Little did I know that, thanks to continuing serendipity, I wouldn’t set foot back in Ann Arbor until a few days before this Fall term.

Within minutes of boarding that plane, I instinctively felt that I was about to experience the most gratifying, unsettling, and enriching journey of my short years. It became a summer that has helped me to unearth my roots and left me with a hunger that’s been eating me alive, yet thankfully not eating me dead. I hope I can awaken a similar appetite in readers of this blog with my anecdotes from my time with Théâtre de la Ville (TDLV) and my first journey into the Old World.

Un Jeu des Rôles au Théâtre de la Ville

Photos: On the left, the two directors: Théâtre de la Ville director Emmanuel Demarcy-Mota and actor Alain Libolt, who plays the role of “Director” in Six Characters in Search of An Author. On the right, rehearsal with sub-titles.

Casually crossing the Pont Neuf on the Seine on the way to my first day, checking-out Notre Dame from the smoker’s balcony (though I don’t smoke), and then finishing my paperwork as the sun set against the Eiffel Tower seemed either the best cliché or too surreal to be true; but it was true, beauty on every corner. However, this type of initial beauty can grow stale with habit, and I quickly found beauty in the fondness my companions as well.

This type of beauty emerged when sharing a simple picnic with the company by the river at lunch, for example. I think the the vitality of a company originates from the unified pulse of its ensemble, that pulse that is universal in any theater venture, regardless of country. Sure, “stage-right” in French might be “the garden” (you can imagine the confusion for me, given that there’s an actual garden in the production). Sure, there may not be such a thing as blocking notes for re-stagings. And maybe the reasons for doing theater at all are very different. Still, the collaborative nature of theater is undeniable across the globe.

Six Characters in Search of an Author is play in which the dramatic truth is juxtaposed with immediate reality. Actors play actors, for example, while directors coach actors to play directors. The lines between performance and reality are crossed. For me, the ideas were constantly in translation as well. Yours truly was tasked with sub-titling the originally Italian text of the play (which is performed in French) into English. Ultimately, the goal for everyone involved, the director, the ensemble, and myself, was the same: To connect the inner life of the play to the outer life of the audience.

La culture ne marche pas!

Photos: On left, sunset as viewed from the theater. On right, the theater, “X”-ed.

I spent two weeks in Italy (turns out speaking Spanish with an Italian inflection doesn’t actually mean you can speak Italian), and upon my return to Paris, I found culture in distress. “Culture,” substantially subsidized by the government and also supported by patrons, was immobilized and in peril due to some impending changes. To put it simply, recent overhauls to labor laws were to compromise the financial security, primarily through alterations to unemployment benefits, of “gypsy” professionals (including actors and stage hands), changing a system which (although not without faults) had long kept the performing arts alive, thriving, and, more importantly, relevant to the society.

The strongest impact on Théâtre de la Ville occurred during its annual city-wide performing arts festival Chantiers d’Europe. The festival saw various performances, all brought from abroad, cancelled as theater venues around the city shut down as part of a strike. TDLV, however remained strong. I learned perhaps my biggest lesson from [Théâtre de la Ville director] Emmanuel Demarcy-Mota when I saw him rally and inspire the company to, instead of shutting down the power of the stage at this time of turmoil, take advantage of the theater’s influence on the city and its audiences. In July, the façade of the theater was crossed with a large white “X” of defiance.

In the midst of the strikes came the opening night for a sold-out run of Pina Bausch – Wuppertal Tanztheatre, a yearly visitor and old friend of TDLV. The company was to perform the “wall”-breaking (both literally and figuratively) Palermo, Palermo. Dramatic truth came from an unexpected place in the bravest and most honest theatrical moment I got to witnessed in France.

Photos: On left, Michael Chase. On right, company and stagehands bow together.

The co-head of the theater, Michael Chase, a reserved man of soft-spoken, tactful, iron words stood center-stage along his company in front of a full house. He softly said that without the workers of the theater, “La culture ne marche pas.” He bent down towards his signature red shoes, untied and removed one of them. He took a step forward as the rest of the company followed his actions.

Later, at the end of the performance, the dancers invited the stagehands, who had built for them, everyday, a brick wall that spanned the proscenium arch, and which tumbled and consequently needed rearranging by the stagehands mid-performance in plain view of the audience, to the stage. They joined the dancers. Everyone took a bow, every single one of them an artist without which “culture wouldn’t move”. And then the curtain fell.

Updated 6/2/2017.