Scoring 100 Years of Hill Auditorium

Meet Howard White, the composer behind the documentary celebrating the 100 years of Hill Auditorium: A Space for Music, A Seat for Everyone, the UMS documentary about our community over 100 years of UMS performances in Hill Auditorium. The documentary will screen on Detroit Public Television (DPTV) on May 19, 2013 at 5 pm.

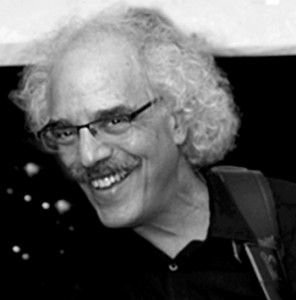

An influential film score composer, particularly for documentaries, Howard White has lived in the Ann Arbor area for many years and is also the owner of The Omni Media Group. UMS’s own video producer and editor Sophie Kruz, the director of A Space for Music, A Seat for Everyone, sat down with Howard to discuss the process of scoring Hill Auditorium’s rich one hundred-year history.

Sophie Kruz: Can you talk a little bit about your background and how you got involved in this project?

Howard White: I’ve been in the music world for many decades. I’ve been doing composition in Ann Arbor for many years, and the last ten years, I have been focusing on film scores for narrative pieces and documentaries especially. That’s how we found each other, through a mutual acquaintance, Chris Cook, who is a really wonderful filmmaker in town. I’ve done maybe a dozen films for him. Being chosen for this project was a nice affirmation of years of work — learning the skills and building the repertoire — so that was very nice, for me to have the opportunity.

SK: What was the first film or TV show that you scored?

Howard White: It was pretty random, and it was a long time ago. I was just starting out in the music world, actually as a performer, producer, musician, and just starting my studio in Ann Arbor when somebody came to me from the art school of all places, asking me to make some music for a film for a master’s thesis. So I said, of course, not knowing anything about what they wanted or how to do it or what was needed. I wrote some songs and did some scoring, but back then, we didn’t have the tools like we have now.

SK: What are the tools you use to do the composition and the recording?

Howard White: In this industry, technology doesn’t drive innovation, but innovation drives technology. Maybe twenty years ago, we just used a multi-track instrumental tool, whereas now we have thousands of instrument samples at our disposal. Before synthesizers, you had a dedicated sample for every note that was hard-coded onto a chip that was embedded right in the hardware of the synthesizer. But now, with high speed processors and hard drives, you are able to store samples.

I’ve been evolving my sample library over the past ten years. To give you a size perspective, I have about a 40 GB string [instruments] library, and it’s just strings. It was recorded on a sound stage in Los Angeles by string players and an orchestra that normally scores film on that stage. There are other libraries out there that are more symphonic that are built for just big sounds, but mine was specifically developed for film scores so it has a nice bright notes and it’s not too big.

The library gives you every articulation, staccato, or sound, so it takes a lot of time to get the precision and the expression. The whole goal is to bring realism to a performance that is really electronic. As much as I would have loved to have scored this with a live orchestra, that’s just impossible these days — only the biggest films do that.

SK: What’s your process for composing? Do you write everything out and then start to record it electronically, or do you compose with a piano?

Howard White: Yes, it’s all piano triggered. I have a large controller keyboard, and it reaches out and grabs sound samples from my many libraries. With our project, I was able to look at the film and get a sense of what you needed, and then sketch out some ideas, and then keep developing and polishing and adding and subtracting from those ideas. Sometimes the idea would be there instantly, sometimes it would take days. I’d start 40 or 50 different pieces before I came up with the one that I sent to you.

SK: What research did you have to do to ground the film sonically to the community of Ann Arbor and Hill Auditorium over the last 100 years?

Howard White: I could search for musical inspiration pretty smoothly from sources as simple as iTunes to more obscure sources like the Library of Congress. I moved chronologically, decade by decade, going through the 100-year history of music I was working to encapsulate. I started in the 1920s, with the ragtime feeling, and then moved to the 30s for a mellower, jazzier sound. I started going down those paths and did some complete pieces, but I realized they weren’t working. The music was fine, but it didn’t match the picture. I could research and develop as much as I want to, but just because the period is correct doesn’t mean it works with the film. I ended up going a more classical, European-inspired route on a particular piece accompanying the story of Rosa Ponselle, and I think it worked really well.

There is a balance between what the music has to say and the story line. For example, when the Frieze Memorial Organ is introduced in the film, I thought it would be really nice to have an organ playing; it’s a little obvious, but sort of appropriate. The organ music that was most commonly played then was certainly Bach, and so I researched numerous inventions that he had done and found one that was lively but not too dramatic. I didn’t quote it exactly, but I used it as an inspiration for the piece.

When we got to the 1960s, I was able to bring in more rock and jazz music, which is closer to my background. I have studied and played classical guitar, but I also play solo piano with a more improvisational jazz style. I was struggling with this 60s piece, so I pulled out my steel-string guitar, because that’s a 60s folk style sound, and the piece just developed from there. When you have Merce Cunningham and John Cage on the screen, I moved to something more edgy and dissonant, but still with the folksy Latin style on top of it.

There was certainly no apprehension about creating this music, but I had to take a deep breath because this was going to be music for music lovers. It had to be up a notch in terms of intelligence and musicality because of the film’s audience.

SK: What are some of the similarities and differences between composing for film and composing for a group?

Howard White: I really like film composing because I’m a visual person. My whole business is interactive design and development, which is why working with music and visuals is a really satisfying melding of the two interests and skill sets. I love just playing and writing. Writing for film is really a special feeling. On one hand, you have the challenge of really amplifying the film and being in concert with the producer, directors of the film, versus when you’re writing music to be out there, then it’s only music. I focus mostly on film scores because that’s just so much more exciting and interesting for me, to work in that medium.

SK: If you were speaking to a young person who was interested in composing original scores for film or television, what advice would you offer them?

Howard White: I started in this business by building up a recording studio with a buddy of mine and working in Ann Arbor doing production for a lot of local bands. After we were done with the gigs, we’d go off and record commercials off the TV, turn off the sound, and score them ourselves. We made a reel and we’d go knock on the doors of producers and ad agencies asking for a chance, showing them what we could do.

My suggestion is to hook up with film makers and art students and anybody who’s doing visual production and do music for them, just collaborate. It’s really a networking world, but that’s all it is. If you have a good ear and you have a good skill set, you’ll make those connections. The key is to find people you need to find to be able to do the work.

Earlier in my career, I spent some time on the west coast to be more embedded in the music world. It was a good location because in big cities like LA, there are more opportunities for networking. There’s a lot you can do: sampling, sample playback, sample editing, and sound design. All of that is different from composing, but there’s a great market out there for sound designers. If you want to compose, you really have to know your theory and harmony, and you have to have a really good ear. You have to make orchestral decisions that make sense and work with the film and your audience. So there are a lot of subtleties and nuances to it that you need to study and just listen. I listen to film scores constantly, just to see what they are doing, why they’re doing it, and how they’re doing it to be able to have that background.

The opportunity to do this film was really special for me and I do absolutely want to thank you, Sophie, and UMS for trusting me to do the film. To hear the music in that beautiful auditorium and to know that it was embedded in a part of UMS history is really a personal thrill for me, and a very high point on my composition career at this point.

Interested in learning more? Listen to the complete interview: